ABSTRACT

This explorative study examines citizens' views on restricting parental freedom to protect children's rights in England, Norway, Poland and Romania. Are there differences in popular views in these four welfare states with different child protection systems, family policies, and approaches to families and children in vulnerable situations? Experimenting between four different parenting problems (unsatisfactory care; alcohol misuse; mental illness; intellectual disability) the findings show that citizens in the four countries have quite similar perceptions of government responsibilities in relation to children suffering from unsatisfactory parental care or parental alcohol misuse. A large majority agree with restricting parental freedom, and a majority agree with intrusive interventions to secure the welfare of the child. There are mixed results on national differences between the east European countries and England and Norway. All, except Norwegians, showed effects on type of parental problems (unsatisfactory care; alcohol misuse; mental illness; intellectual disability) for agreement on type of interventions, indicating that citizens expect differential treatment of parents' dependent on the reason for negligent care of children. Perhaps the Norwegians does not differentiate because they regard the risk to the child as similar regardless of parental problems, which may reflect a child centrism in the Norwegian population.

SAMMENDRAG

I denne artikkelen undersøkes representative utvalg av innbyggerne i England, Norge, Polen og Romania sine vurderinger av terskler for å gripe inn i familien for å beskytte barnets beste. Resultatene viser at befolkningens synspunkter i disse fire velferdsstatene, som har forskjellige barnevernsystemer, familiepolitikk og tilnærminger til familier og barn i sårbare situasjoner, er på noen områder ganske like. Et stort flertall er enig i at staten må begrense foreldrenes frihet, og et flertall er enig i å flytte barnet for å sikre barnets beste. Institusjonell kontekst ser ut til å spille en rolle ved at det er forskjeller mellom de østeuropeiske landene på den ene siden, og England og Norge på den andre siden. Testing av om type foreldreproblemer (utilfredsstillende omsorg/ alkoholmisbruk/ psykisk sykdom/ intellektuell funksjonshemning) ift villighet til å gripe inn, gir utslag i den Engelske, Polske og Rumenske befolkningen og det indikerer at innbyggerne forventer forskjellsbehandling avhengig av årsaken til omsorgssvikt. At det ikke gir utslag i den norske befolkningen, kan skyldes at de ser på risikoen for barnet som den sammen, uavhengig av foreldrenes problemer, noe som kan være uttrykk for en barnesentrisme i den norske befolkningen.

Introduction

Norway’s hidden scandal was the title of a BBC news report in 2018 (Whewell, Citation2018) that gained attention across Europe. The BBC report was echoing harsh criticism of the Norwegian child protection system and how it handled protection of children’s rights, from citizen organisations, religious bodies, and ultra-conservative groups. At the same time, Norway is consistently ranked high on all measures of children’s rights and well-being (Clark et al., Citation2020), as well as in relation to the Sustainable Development Goals for children (UNICEF Innocenti, Citation2020, see Richardson et al., Citation2017), prosperity measures (The Legatum Institute, Citation2020) and the rule of law (World Justice Project, Citation2020). This creates a puzzle. Surely, the normative nature and the indeterminacy of child protection decisions make it inevitable that interventions are contested, so the legitimacy of the child protection system will be questioned. In most child protection systems of which I am aware, front-line staff or the courtsFootnote1 are criticised for intervention or failure to intervene (Berrick et al., Citationin press; Burns et al., Citation2017; Gilbert et al., Citation2011a, Citation2011b; Skivenes et al., Citation2015). However, the criticism of child protection systems seems to have reached a new level that is massive, international, co-ordinated and based on social media. This is illustrated by many demonstrations across the world against the Norwegian child protection system (see Jakobsen, Citation2018) as well as strong criticism of the Norwegian government from several east European countries; for example, Poland granted asylum to a Norwegian woman on the run from the child protection system (Moody, Citation2018), and Czech political leaders compared Norway to Nazi Germany (Lohne et al., Citation2015). With social media facilitating uncensored discussions and statements, it may be easy for critics to target a system that already has a bad reputation – as the Norwegian system now has. However, the criticism may also reflect genuine differences between attitudes in countries and societies towards children and the extent to which their rights are and should be protected by the state. These differences may involve standards for the protection of children from mistreatment and neglect forming the legitimate threshold for interventions into the family. This paper is the first step to explore differences in popular views and attitudes towards child protection interventions between England, Norway, Poland and Romania. The paper seeks answers to three questions. First, with what types of government intervention do citizens agree or disagree? Second, what parental problems or capacities are generally acceptable to citizens? Third, are there differences between national populations?

The data for this study are from a representative sample of the populations of each of the four above-mentioned countries. Poland and Romania are chosen because they represent two east-European countries that have expressed a clear critique of child protection interventions in other countries, and they have a child protection system that is assumed to be different both from the English and Norwegian system. The study takes an explorative experimental survey approach because there is in general little knowledge about populations’ attitudes to child protection (Helland et al., Citation2018, Citation2020; Juhasz & Skivenes, Citation2016; Todahl et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, we know very little about the child protection systems in Poland and Romania, so we have little sense or good data on child protection policy and practice in these two countries. In contrast, both England and Norway have good research bases on child protection interventions and several studies of popular views on children and child protection, which gives us something to build on and some expectation of what we can find.

The paper is structured as follows. The next section outlines theory and existing research, and it is followed by a methods section and findings. The paper ends with concluding remarks.

Children’s rights and child protection

Recent decades have brought children onto the agenda in new ways, and we observe that children in many societies are increasingly regarded as individuals with separate interests and rights laid out in the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which has been ratified worldwide. The child protection systems in the four countries under study have all ratified the CRC, and article 19 expresses the state responsibility to protect children

… from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment or exploitation, including sexual abuse, while in the care of parent(s), legal guardian(s) or any other person who has the care of the child.

Table 1. Prevalence of three problems in Europe and four countries. Percentage of population.

Institutional context, mass media and existing research

Through a child protection system,Footnote3 the state can assume parental responsibility or terminate all parental rights when parents are unable or unwilling to fulfil their parental obligations. This is considered one of the most invasive and consequential decisions a state can make, and it is highly necessary when child well-being is at stake. These interventions represent immense state power, simultaneously challenging individual freedoms as well as the privacy and autonomy of family life (Brighouse & Swift, Citation2006; Schapiro, Citation1999; Sutherland, Citation2017). Therefore, such decisions must be legitimised through some form of acceptance by citizens (Suchman, Citation1995; Zelditch, Citation2004; Zelditch & Walker, Citation2003), be of high quality and withstand public scrutiny (Habermas, Citation1996; see Rothstein, Citation1998). Citizens in a jurisdiction are the rightful lawmakers, and their political authority is based on support from the electorate, albeit not solely. Studying people’s views of various public interventions is not uncommon: for example, public health policy intervention in relation to tobacco and alcohol (Diepeveen et al., Citation2013). These studies are important not only to gain knowledge on what citizens find acceptable in terms of state interventions with citizens but also to understand why some interventions work whereas others do not. In political science, elections and voter behaviour are typically a focus of study. However, there is also a growing body of literature on the impact of government actions and the alignment of their production of goods and services with citizens’ needs and requirements (Rothstein, Citation1998, Citation2009; Svallfors, Citation2012). This paper is situated in this tradition, and a rather straightforward approach is applied in this population-level study of views on child protection interventions that combines explorative and experimental design (more on this in the Methods section).

There is a scarcity of research and knowledge of citizens’ views on the government’s responsibility for children at risk of abuse and neglect. Regular social studies on attitudes, such as the European Social Survey (ESS), typically do not include questions about child protection or children’s rights, so there is little general information available on which to base expectations. A review of existing systematic reviews about research on children at risk on Web of Science in May 2020 found no studies of popular attitudes. We know that countries have established different child protection systems and thresholds for interventions (Berrick et al., Citationin press; Gilbert et al., Citation2011a, Citation2011b) and differ in their processes for removals (Burns et al., Citation2017). Institutional context and cultural values in a country are likely to reflect and influence the values of a society (March & Olsen 1989; Rothstein, Citation1998). This has also some empirical evidence in studies of citizens’ attitudes to welfare (Blekesaune & Quadagno, Citation2003; Diepeveen et al., Citation2013; Valarino et al., Citation2018). A basic premise for this type of policy theory is that public opinion is regarded as an independent variable that explains, or has an impact on, politicians and then again how policy is developed. In this paper, public opinion is regarded as a dependent variable, in which policies and welfare institutions influence citizens attitudes and their views on the role and status of the welfare systems (see also Svallfors, Citation1996, Citation2012; Valarino et al., Citation2018).

The institutional context of interventions in response to parental neglect or abuse is a country’s child protection system, which has the responsibility to protect and secure children at risk, as CRC Article 19 prescribes. In the literature is a global typology of five types of child protection systems, which is a conceptualisation of cumulative hierarchies of childhood risk that records the typical strategies in each type (Berrick et al., Citationin press).Footnote4 In institutionalised contexts, including high-income countries in Europe, the three applicable systems are the child maltreatment-protective systems, child well-being-protective systems, and child rights-protective systems. Child maltreatment-protective systems are intended to prevent harm and secure the safety of the child, with a high threshold for state interventions and few service provisions for families (a risk-oriented system such as that described by Gilbert et al., Citation2011b). Both Poland and Romania have this type of system (see Helland, Citation2020). In addition, a child well-being protection system will attend to families’ and children’s needs for support and services, and thus have a low threshold for provisions and interventions (the service-oriented system described by Gilbert et al., Citation2011b). The English system would be categorised as between a well-being system and a child maltreatment system (Thoburn, Citationin press). Finally, there are rights-protective systems, in which the full range of children’s rights are protected by the state and the child is protected and respected as the bearer of individual rights within the private family sphere. Norway would be categorised as having such a system (Hestbæk et al., Citationin press; Skivenes, Citation2011).

The relation between critique of public administration in the mass media and citizens opinion’s, as referenced in the introduction, is complex. Original ideas of the press being driven by social responsibility and enlightenment ideals (a civic model) are challenged by recent developments of technology, competition, commercialisation, decreasing voter loyalty, and reality orientations (Brants & de Haan, Citation2010). The aim of the mass media seemed thus to have transitioned into or been supplemented with a strategic model and/or an emphatic model. The strategic model has a focus on presenting news and information in a sensational and/or entertaining way, whereas the empathic model has a partisan and populist format (see Brants & de Haan, Citation2010, p. 417 ff for details). These models may shed some light on citizens perceptions and media coverage.

Studies of popular views of state interventions show that degree of intrusiveness matters. This is also shown in a systematic review of the public acceptability of government intervention to influence health-related behaviours (Diepeveen et al., Citation2013). Less intrusive interventions have more support than more intrusive ones. This is found in a study of popular views of ‘nudging’ in eight countries, leading the authors to title the paper A worldwide consensus on nudging? Not quite, but almost (Sunstein et al., Citation2018). The systematic review by Diepeveen et al. (Citation2013) showed that people were more accepting of restrictions on the behaviour of others , in contrast to restrictions on their own. The researchers also found that female or older respondents had greater acceptance of interventions (Diepeveen et al., Citation2013). Restrictive policies already in place had greater support, and policies that targeted children and young people received greater acceptance from the population.

Some empirical studies of citizens views of child protection intervention thresholds and adoption versus foster home practices report similar findings (Berrick et al., Citation2019; Skivenes & Tefre, Citation2012; Skivenes & Thoburn, Citation2017). However, there are also some discrepancies and contradictions in the correlations between ongoing system practices and popular attitudes. In a study of adoption from care, the populations of Finland and Norway are far more supportive than the actual practices in those countries would indicate (see Helland et al., Citation2020; Skivenes & Thoburn, Citation2017). In another study of attitudes in four countries to a possible neglect situation for two children and the child protection system’s response, the institutional context is sometimes but not consistently in alignment with popular opinion (Berrick et al., Citation2019).

In terms of individual background variables, existing research also reports mixed results. Citizens with left-leaning political orientations, women, younger people and those with higher education take a more positive view of child protection interventions and/or more confidence in the system and decision makers (Helland et al., Citation2020; Juhasz & Skivenes, Citation2016; Sentio, Citation2019; Skivenes & Thoburn, Citation2017), but again, the results are not consistent.

Data and methods

The aim of the survey was to test how a representative sample of the population in four countries – Norway, England, Poland and Romania – regarded the child’s best interests and government responsibility in various scenarios of negligent care. The survey was funded by the Norwegian Research CouncilFootnote5 and EEA Grants.Footnote6 Data were collected from a representative sample of the populations of Norway (N = 1047), England (N = 1012), Poland (N = 1009) and Romania (N = 1009). The survey was distributed to respondents in week 37 of 2019 in Norway and in week 39 in England, Poland and Romania. The samples of respondents (18+ years old) were nationally representative in relation to observable characteristics (gender, age and location). In Norway, representativeness in relation to gender and age was controlled for within each region. If a demographic was under-represented in the sample, more respondents were recruited to ensure representativeness. Finally, the sample was weighted for accurate representativeness (given the variables used for this). For the background questions, we used standard formulations provided by the data collection bureau, Response Analyse. The bureau was responsible for implementing the survey questions developed by the researcher and collecting data in all four countries. The researcher did not receive any identifying data about any study participants. There was no link between survey responses and participant identity. A general overview of this type of data collection process can be found at: https://discretion.uib.no/projects/supplementary-documentation/population-surveys/

Survey statements

Respondents were asked to respond to short statements in which two premises are made explicit: (1) children’s well-being suffers due to their parent’s care; and, (2) the reason for the governments concern or intervention is the child’s best interests. Using the exact same baseline wording, the ten statements change words in the statements to test the degree to which some family problems (unsatisfactory care/alcohol misuse/mental illness/intellectual disability), interventions (demand changes/move the child), service provision (added information), and explicit mentioning use of force (demand/coerce). Statements were developed in English by the researcher, and translated to Norwegian, Polish, and Romanian by native researchers. The translations were then again tested for accuracy by one or more native speaking persons for each language. Each participant was randomly assigned to one of the following ten statements resulting in a total number of respondents assessing each of the statements to around 400. The participants scored on an ordinal scale from 1 to 7 on the degree to which they agreed with a statement. In the following the survey statements are presented:

Please indicate how much you agree or disagree with the following (1 = No, I very much disagree – 7 = Yes, I very much agree):

B1.

A child’s welfare suffers due to unsatisfactory care from its parents. In such circumstances, is it acceptable that the authorities demand the parents make changes, because it is in the child’s best interests?

B2.

A child’s welfare suffers due to unsatisfactory care from its parents. In such circumstances, is it acceptable that the authorities coerce the parents to make changes, because it is in the child’s best interests?

B3.

A child’s welfare suffers due to its parents’ alcohol misuse. In such circumstances, is it acceptable that the authorities demand the parents’ make changes, because it is in the child’s best interests?

B4.

A child’s welfare suffers due to its parents’ mental health illness. In such circumstances, is it acceptable that the authorities demand the parents’ make changes, because it is in the child’s best interests?

B5.

A child’s welfare suffers due to parental intellectual disability. In such circumstances, is it acceptable that the authorities demand the parents make changes, because it is in the child’s best interest?

B6.

A child’s welfare suffers due to unsatisfactory care from its parents. In such circumstances, is it acceptable that the authorities move the child from its parents to other caregivers, because it is in the child’s best interests?

B7.

A child’s welfare suffers due to its parents’ alcohol misuse. In such circumstances, is it acceptable that the authorities move the child from its parents to other caregivers, because it is in the child’s best interests?

B8.

A child’s welfare suffers due to its parents’ mental health disorder. In such circumstances, is it acceptable that the authorities move the child from its parents to other caregivers, because it is in the child’s best interests?

B9.

A child’s welfare suffers due to parental intellectual disability. In such circumstances, is it acceptable that the authorities move the child from its parents to other caregivers, because it is in the child’s best interests?

B10.

A child’s welfare suffers due to unsatisfactory care from its parents, and assistance services do not lead to improvement. In such circumstances, is it acceptable that the authorities move the child from its parents to other caregivers, because it is in the child’s best interests?

Data were analysed with SPSS 25 statistical software, presenting n, mean value, Std. deviation, Std. error, Mean Conf. interval, min–max range, for ten statements per country and total sample. Figures with 95% confidence interval bars were created with Excel spreadsheets, with the awareness that this interval shows the margins of what is sound to report. Given the explorative purpose of this survey, I focus on the effects of type of parental problems and willingness to move a child from their parents (B6, B7, B8, B9) as this is an intrusive intervention and as such a test of a hard case. In an online Appendix, results for the following statements are expanded on: B1 and B2 the use of ‘demand’ versus ‘coerce’. Furthermore, B1, B3, B4, B5 the use of demand changes in relation to ‘unsatisfactory care’ / ‘parents’ alcohol misuse’ / ‘parents’ mental health illness’ / ‘parental intellectual disability’. Finally, findings from B6 versus B10, with and without service provision respectively, are also elaborated in Appendix. The Appendix can be found at: https://discretion.uib.no/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Skivenes-in-press-Exploring-populations-view-on-thresholds-and-reasons-for-child-protection-intervention.pdf.

Limitations

Although the study has a unique survey material, there are some obvious limitations. There are around 400 respondents to each of the ten statements, and although the composition of respondents is randomised and not deviating much from the total sample, the sample size on country level (approx. 100 respondents on each statement) is small and thus all findings are only indications and must be tested with larger samples. Furthermore, the small sample prohibits me for undertaking more detailed analysis of background variables. The interpretations of the meaning of the statements will inevitably vary, for example the understanding of terms such as ‘misuse’, ‘demand changes’, or ‘unsatisfactory’ although the experimental design test out some of the conceptual vagueness. The survey may also include biases that I am unaware of, and the representativeness of samples are secured on some variables, and thus as in all opinion surveys, this may not be sufficient to include all subgroups in a population.

Findings

The purpose of this population survey, applying an experimental design, was to explore if there are different views in populations for when to intervene; if the parental problems were of importance for respondents’ opinions, and the acceptance of various intrusive interventions.

Starting with the main question for this study, the findings indicate that 75% of the populations agree that the government should remove a child if his/her well-being suffers owing to unsatisfactory care, with a mean value of 4.9 (see Figure 8 in the Appendix and ). There are differences between countries, with England (86% agreeing, mean 5.3) and Norway (84% agreeing, mean 5.3) at one end and Poland (58% agreeing, mean 4.3) and Romania (55% agreeing, mean 4.9) at the other (see and and Figure 8 in the Appendix). Poland scores significantly lower (at the 95% level) than England and Norway (see ).

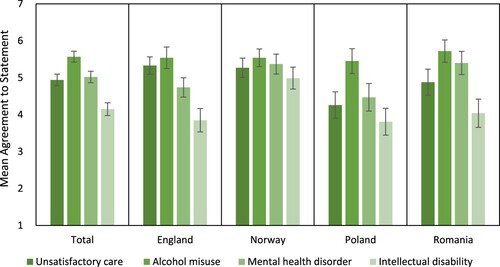

Figure 1. Mean values for removing the child owing to unsatisfactory care vs. alcohol misuse vs. mental health disorders vs. intellectual disability; 95% confidence interval bars.

Note: 1 = No, I strongly disagree, 7 = Yes, I strongly agree. Highest n = 456. Unsatisfactory care statement: ‘A child’s welfare suffers due to unsatisfactory care from its parents. In such circumstances, is it acceptable that the authorities move the child from its parents to other caregivers, because it is in the child’s best interests?’ For this statement the total n = 413; for England N = 102; for Norway N = 111; for Poland N = 105; and, for Romania N = 95. Alcohol misuse statement ‘A child’s welfare suffers due to its parents’ alcohol misuse. In such circumstances, is it acceptable that the authorities move the child from its parents to other caregivers, because it is in the child’s best interests?’ For this statement the total n = 398; for England N = 95; for Norway N = 95; for Poland N = 99; and, for Romania N = 109. Mental health disorder statement: ‘A child’s welfare suffers due to its parents’ mental health disorder. In such circumstances, is it acceptable that the authorities move the child from its parents to other caregivers, because it is in the child’s best interests?’ For this statement the total n = 456; for England N = 129; for Norway N = 114; for Poland N = 91; and, for Romania N = 122. Intellectual disability statement: ‘A child’s welfare suffers due to parental intellectual disability. In such circumstances, is it acceptable that the authorities move the child from its parents to other caregivers, because it is in the child’s best interests?’ For this statement the total n = 427; for England N = 120; for Norway N = 105; for Poland N = 118; and, for Romania N = 84.

Table 2. N, mean value, Std. deviation, Std. error, Mean Conf. interval, min–max range, for ten statements per country and total sample (1–7 scales, 1 = No, I strongly disagree, 7 = Yes, I strongly agree).

The populations are clear on the necessity for something to be done, which is evident in response to the question of whether the government should choose less intrusive interventions or demand that the parents change how they care for a child.Footnote7 The mean value is 5.45, and all countries have a mean value above 5.2 (Poland), the highest being 5.8 (Romania); see . There are no significant differences between the countries on this variable (see Figure 2 in the Appendix).

The findings further show treatment effects in relation to the reason given for the child’s well-being suffering. In the experiment, unsatisfactory care is specifically distinguished as child suffering owing to parental alcohol misuse, mental health disorders or intellectual disability. The treatment effect is also evident in the population sample from England, and partly in Poland (alcohol misuse and mental health) and Romania (mental health and intellectual disability); see .

The following details are displayed based on agreement and mean scores (see Figures 9, 10 and 11 in the Appendix and ): alcohol misuse (86% agreement; mean score of 5.6), mental health disorders (73% agreement; mean score of 5) and intellectual disability (56% agreement; mean score of 4.2). There are significant differences between these three parental problem situations (see ). In each country, the results are similar in terms of the order of parental problems and agreement with removal of a child, with alcohol abuse having the highest score, followed by mental health disorders and intellectual disability (see ).

However, there are country differences (see ). In Norway, there are no significant differences between the four treatments. In England, scores for unsatisfactory care and alcohol misuse are significantly higher than mental illness and intellectual disability. In Poland, scores for alcohol misuse are significantly higher than those for the other situations. In Romania, scores related to intellectual disability are significantly lower than those for the other situations; alcohol misuse and mental health are at the same level, as are mental health and unsatisfactory care.

Across populations, alcohol misuse is considered a reason for removing a child from parental care. Agreement in increasing order is 79% of the Polish population, 86% in Romania, 87% in England and 93% in Norway. Measured on mean values there are no significant differences between country populations in this situation (see ).

There are country differences concerning the views of parental mental health disorder: Romania (80% agreement; mean score of 5.4); Norway (78% agreement; mean score of 5.4); England (72% agreement; mean score of 4.7) and Poland (60% agreement; mean score of 4.5) (see Figure 10 in the Appendix and ). Romania scores significantly higher than Norway, while Norway and Romania score significantly higher than England and Poland (see and ).

The parental problem that produced the least support for intervention is parental intellectual disability. A total of 58% agreed (mean score of 4.2) that the government should remove a child that suffered for this reason. However, there are country differences (see Figure 11 in the Appendix and ). Norway showed 73% agreement (mean score of 5), followed by Romania (54% agreement; mean score of 4), then 48% in both England (mean 3.9) and Poland (mean 3.8). There are significant differences between Norway and the other three country populations in relation to intellectual disability (see ).

Does choice of word – demand vs. coerce – matter?

An examination of whether the use of ‘demand’ (B1) versus ‘coerce’ (B2) influences people’s views on state intervention shows no significant difference either overall or in the individual countries (see and Figure 1 in the Appendix).

Does service provision matter?

An examination of the impact of whether services are provided (B10) or not (B6) on popular views on removal of a child by authorities shows no significant difference in the overall population sample. Nor are there differences in the country samples, except for England, where there is greater acceptance of removal when services have been provided (see and Figure 7 in the Appendix).

Demand a change?

The impact of unsatisfactory care in relation to a specific parental problem on agreement that the authorities should demand a change in parental behaviour in the interests of a child’s welfare was assessed. Overall, the results are similar to those for removing the child but with higher mean values. The four problem descriptions tested: ‘unsatisfactory care’ (B1); ‘alcohol misuse’ (B3); ‘mental health illness’ (B4); and ‘intellectual disability’ (B5) (see and Figure 2 in the Appendix) show significant differences between some of the treatments, especially if a child suffers owing to parental alcohol misuse. This stands out in the total sample as well as within countries.

Discussion

Two striking findings are evident from this paper on citizens’ attitudes toward child protection, and the government’s responsibility to intervene if parents are unwilling or unable to care for their children, as stated in CRC Article 19. First, the consensus is that it is necessary for the state to intervene and to restrict parental freedom. Second, there is a high degree of similarity across these four country populations.

It is a strong and clear finding that people agree that governments have a responsibility to restrict parents’ freedom if a child’s welfare is suffering. A large majority – more than eight out of ten respondents – expect the state to demand changes in parental behaviour; interestingly, using the term ‘coerce’ did not change the results. Furthermore, a majority also support removal of the child from his/her parents in these circumstances. The expressed reason for intervention is the child’s well-being, and I interpret this finding as an indication on what the literature characterises as child centrism in societies (Berrick et al., Citationin press; Pösö et al., Citation2014; Skivenes, Citation2011; Skivenes & Strandbu, Citation2006). The term ‘child centrism’ includes an understanding of societies undergoing transformation in perceptions and treatment of children and young people as well as respect for and protection of their rights. The emerging position of children in societies is that of individuals on an equal footing with others, underpinned by the strong rights in the CRC, which has gained universal commitment across the world. This position is observable in policies (Berrick et al., Citationin press; Daly, Citation2020), in legislation such as bans on corporal punishment (Helland et al., Citation2018, Citation2020; Skivenes & Stenberg, Citation2013) and in the increased weight given to children’s participation in administrative proceedings (Daly, Citation2018; Gal & Duramy, Citation2015; Kriz, Citation2020). In a large majority of each of the four populations it is evident that parental alcohol misuse is considered sufficient justification for government intervention, and there seems to be no correlation with the actual prevalence of alcohol misuse in the four countries (see ). For example, the high prevalence in Poland does not appear to result in a more lenient attitude in the Polish population. Overall, the conclusion on the question about government responsibility for child protection and popular support for restricting parental freedom is that intrusion is agreeable for most citizens in these four countries.

The next question relates to the effect of the type of parental problem on peoples’ attitudes to interventions. The treatment effects in this study are clear. Overall, there are significant differences between parental circumstances. A majority of citizens support interventions by the state in response to parental alcohol misuse, mental health disorders and intellectual disability, in that order, and the same treatment effects are evident for the intrusive intervention. Possible explanations for these results may be that alcohol misuse, and its consequences for parental capacity, is well known to people. In addition, people may believe that the child has been exposed to alcohol during pregnancy and thus has special needs. People may have less knowledge about mental illness and intellectual disability, which may influence their views, but perhaps a stronger explanation is that both problems are beyond an individual’s control. Genetic disposition is not something that one can discard, although there may be treatment or medication for mental health problems. The discussion around alcohol misuse, and whether it is a disorder or a self-inflicted and blameworthy action, is ongoing, but the sentiment is likely to be that people believe this to deserve blame (Schomerus et al., Citation2011; see also Fortney et al., Citation2004). It may be considered that government or others have a responsibility to support people with either mental illness and intellectual disability with services and treatment, and possibly these two problems have less stigma or a different type of stigma from alcohol misuse.

The findings from this study show that populations in four different welfare states, with different child protection systems and different family policies and approach to vulnerable families, are quite similar in their perceptions of government responsibilities when a child is suffering from unsatisfactory parental care. The majority agree with intrusive interventions such as removal in the best interests of the child. The expectation that there would be stark country differences between the former east European countries versus England and Norway was fulfilled when the standard is unsatisfactory care from parents. However, when asked about a specific parental problem, alcohol misuse, mental health problems or intellectual disability, there is a high degree of agreement across country populations about alcohol misuse, indicating that people regard this a serious problem and probably incompatible with parenting a child. It may also reflect a normative bias against alcohol misuse.

Furthermore, for three countries – England, Poland and Romania – there are treatment effects, whereas in Norway this is not the case. The explanation for this may be a view that the risk to a child is similar for all the parental problems, so an intervention is required regardless. It may be that the Norwegian population is more child centric than others. Comparative studies indicate that Norwegian citizens show significantly stronger support for children’s rights (e.g. Helland et al., Citation2018, Citation2020; Skivenes & Thoburn, Citation2016). Furthermore, the Norwegian child protection system is categorised as a children’s rights-oriented system (Berrick et al., Citationin press).

The populations of England and Poland follow the same tendency for interventions in the mental health problem treatment to be scored significantly lower than alcohol misuse, whereas Romania does not have this effect. It may be speculated that this is because there is a different approach to mental health problems in Romania and a stigma on such illnesses.

In all four countries, intervention in response to intellectual disability has the lowest average support, but in England and Romania there is significantly less support for interventions than there is in response to the two other parental problems. Intellectual disability is not expected to change with treatment or medication, but it can be accommodated with support and services. The policy debates on disability and assistance for this group of citizens indicates huge differences in Europe (European Commission, Citation2017; Hvinden, Citation2003; see also Anema et al., Citation2009). Intellectual disability cannot be blamed on individual choices, so perhaps people are less agreeable to interventions. I have not examined whether service provisions would have changed respondents’ views on interventions with parents with intellectual disability, but the findings from the study show that service provision did not change people’s willingness to remove a child from his/her parents (see Appendix, Figure 7).

Concluding remarks

This paper explores new territory by conducting an experimental study of citizens’ opinions on child protection in England, Norway, Poland and Romania. Overall, there is little knowledge of popular views on child protection and children’s rights, and an important reason for this study is to fill this gap. The choice of countries is also guided by strong criticism from many European news outlets, especially from eastern European politicians and citizen groups, with the Norwegian child protection system singled out for being unfair and unaccountable. A pertinent question following this criticism is whether it reflects the value positions of a society, and whether there are fundamental differences between populations. The results cannot confirm stark differences between citizen groups overall, as there is evidence of agreement on child protection interventions. Thus, the flood of criticism in the mass media and social media does not represent general sentiment in the populations. This is an important finding and may have implications for how to reflect on the legitimacy of child protection systems, as well as the standing of children’s rights in a society. Citizens in all four countries give children’s rights priority over rights to family privacy in specific situations and indicates a child centrism in these countries. Another implication of the finding is to be cautious about massive media coverage and mass media’s outcry and call for reform. It cannot be assumed that extensive media critique is a direct measurement of citizens opinions and view on what is right to do. Possibly the tendency in many societies is that mass media increasingly is employing an empathic model of news presentation, in which it is bonding with its audience and supporting the victims of flaws and personal errors within public administration (see Brants & de Haan, Citation2010).

Given more specific threats to a child’s wellbeing, the picture changes and there are treatment effects – except for Norwegian citizens as this comparison suggests their attitudes are unaffected by parental problems. These differences in treatment effects between countries are difficult to explain with these data, and further examination must be undertaken.

Although the findings from this study are a measure at a single point in time, and studies with larger samples are clearly required, I believe if the findings are considered in addition to those of other studies, it is possible to distinguish child centrism in popular attitudes which indicates a change in traditional views on family privacy. The new emerging position is that many citizens support prioritising children’s rights over parental rights, and this allows unmediated state responsibility for respecting and protecting children’s rights.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (69.5 KB)Acknowledgements

I am grateful for assistance from Dr Gabriel Badescu and Dr Marta Danecka for translating the questions from English to Romanian and Polish, respectively. Thanks to Dr Ingi Iusmen (Romania), Lukas Koerdt (Poland), PhD students Hege Stein Helland and Ida Juhasz (Norway), for reliability testing translations. Furthermore, many thanks to Dr Baniamin for organising data files, and running a few tests in SPSS, and thanks also to research assistant Vanessa T. Seeligmann for reliability testing results and making presentable figures and tables. I am very much grateful to two anonymous reviewers for constructive comments and input to the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marit Skivenes

Professor Marit Skivenes has a PhD in political science at the Department of Political Science and the director of the Centre for Research on Discretion and Paternalism, University of Bergen, Norway. Skivenes is the PI of several international research projects on the child protection system and has received a Consolidator grant from the European Research Council. Skivenes has written numerous scientific works on child protection decision-making, children’s rights, migrant children, and child welfare system and broader welfare issues, as well as being an editor on the Handbook on child protection systems (Oxford University Press). Prof. Skivenes has recently been appointed to lead the Norwegian Governments expert committee on child protection (2021–2023).

Notes

1 In child protection cases, it is typically the courts or court-like decision-making bodies that decide on intrusive interventions.

2 A severity of disability indicator was calculated by adding the number of life areas where a respondent encounters a barrier associated with a health problem or a limitation on a basic activity. The following levels were created: LD1 Barriers to participation in 1 life domain; LD2–3 Barriers to participation in 2–3 life domains; LD_GE4 Barriers to participation in four or more life domains (Eurostat, Citation2015).

3 The term ‘child protection’ characterizes systems that are responsible for children at risk of harm or neglect from their caregivers or who may be at risk of harming themselves or others. In some countries, these may be referred to as ‘child welfare systems’ and some states combine child protection with social services, health or education. These may be referred to as ‘social services’, ‘family services’ or other terms.

4 These five systems are: child exploitation-protective systems; child deprivation-protective systems; child maltreatment-protective systems; child well-being-protective systems, and child rights-protective systems.

5 The acceptability of child protection interventions. A cross-country analysis. Project number: 262773. https://prosjektbanken.forskningsradet.no/#/project/NFR/262773

6 Cosmopolitan turn and democratic sentiments: The case of child protection services. Project code: EEA-RO-NO-2018-0586. https://www.discretion.uib.no/projects/consent/

7 Popular views on ‘demanding changes’ (B1, B3, B4, B5) versus ‘remove the child’ (B6, B7, B8, B9) under four different circumstances differed, with a higher agreement to intervention when the restrictions are lighter (see Figure 2 in Appendix).

References

- Anema, J. R., Schellart, A. J. M., Cassidy, J. D., Loisel, P., Veerman, T. J., & van der Beek, A. J. (2009). Can cross country differences in return-to-work after chronic occupational back pain be explained? An exploratory analysis on disability policies in a six country cohort study. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 19(4), 419–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-009-9202-3

- Berrick, J. D., Dickens, J., Pösö, T., & Skivenes, M. (2019). Children’s and parents’ involvement in care order proceedings: A cross-national comparison of judicial decision-makers’ views and experiences. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 41(2), 188–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/09649069.2019.1590902

- Berrick, J. D., Gilbert, N., & Skivenes, M. (Eds.). (in press). International handbook on child protection systems. Oxford University Press.

- Blekesaune, M., & Quadagno, J. (2003). Public attitudes toward welfare state policies: A comparative analysis of 24 nations. European Sociological Review, 19(5), 415–427. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/19.5.415

- Brants, K., & de Haan, Y. (2010). Taking the public seriously: Three models of responsiveness in media and journalism. Media, Culture & Society, 32(3), 411–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443709361170

- Brighouse, H., & Swift, A. (2006). Parents’ rights and the value of the family. Ethics, 117(1), 80–108. https://doi.org/10.1086/508034

- Burns, K., Pösö, T., & Skivenes, M. (Eds.). (2017). Child welfare removals by the state. Oxford University Press. https://www.akademika.no/child-welfare-removals-state/9780190459567.

- Clark, H., Coll-Seck, A. M., Banerjee, A., Peterson, S., Dalglish, S. L., Ameratunga, S., Balabanova, D., Bhan, M. K., Bhutta, Z. A., Borrazzo, J., Claeson, M., Doherty, T., El-Jardali, F., George, A. S., Gichaga, A., Gram, L., Hipgrave, D. B., Kwamie, A., Meng, Q., … Costello, A. (2020). A future for the world's children? A WHO–UNICEF–Lancet Commission. The Lancet, 395(10224), 605–658. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32540-1

- Daly, A. (2018). Children, autonomy and the courts: Beyond the right to be heard. Brill Nijhoff. https://brill.com/view/title/35870.

- Daly, M. (2020). Children and their rights and entitlements in EU welfare states. Journal of Social Policy, 49(2), 343–360. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279419000370

- Diepeveen, S., Ling, T., Suhrcke, M., Roland, M., & Marteau, T. M. (2013). Public acceptability of government intervention to change health-related behaviours: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 756–767. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-756

- European Commission. (2017). Progress report on the implementation of the European Disability Strategy (2010—2020) (SWD(2017) 29 final). https://www.eumonitor.eu/9353000/1/j9vvik7m1c3gyxp/vkt9d83wv6yw#p1.

- Eurostat. (2015). Prevalence of disability (source EHSIS) (hlth_dsb_prve). Eurostat, the Statistical Office of the European Union. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/metadata/en/hlth_dsb_prve_esms.htm.

- Eurostat. (2020). Statistics explained: Mental health and related issues statistics. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/pdfscache/37380.pdf.

- Fortney, J., Mukherjee, S., Curran, G., Fortney, S., Han, X., & Booth, B. M. (2004). Factors associated with perceived stigma for alcohol use and treatment among at-risk drinkers. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 31(4), 418–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02287693

- Gal, T., & Duramy, B. (Eds.). (2015). International perspectives and empirical findings on child participation: From social exclusion to child-inclusive policies. Oxford University Press.

- Gilbert, N., Parton, N., & Skivenes, M. (2011a). Changing patterns of response and emerging orientations. In Child protection systems: International trends and orientations (1st ed., pp. 243–257). Oxford University Press.

- Gilbert, N., Parton, N., & Skivenes, M. (Eds.). (2011b). Child protection systems. Oxford University Press. https://www.akademika.no/child-protection-systems/9780199793358.

- Habermas, J. (1996). Between facts and norms: Contributions to a discourse theory of law and democracy (W. Rehg, Trans.; First paperback edition 1998). The MIT Press.

- Helland, H. S., Kriẑ, K., Sánchez-Cabezudo, S. S., & Skivenes, M. (2018). Are there population biases against migrant children? An experimental analysis of attitudes towards corporal punishment in Austria, Norway and Spain. Children and Youth Services Review, 85, 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.12.012

- Helland, H. S., Pedersen, S. H., & Skivenes, M. (2020). Adopsjon eller offentlig omsorg? En studie av befolkningens syn på adopsjon som tiltak i barnevernet. Tidsskrift for samfunnsforskning, 61(2), 124–139. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1504-291X-2020-02-02

- Helland, T. (Ed.). (2020). A comparative analysis of the child protection systems in the Czech Republic, Lithuania, Norway, Poland, Romania and Russia. Centre for Research on Discretion and Paternalism.

- Hestbæk, A.-D., Skivenes, M., Falch-Eriksen, A., Svendsen, I., & Bache-Hansen, E. (in press). The child protection system in Denmark and Norway. In J. D. Berrick, N. Gilbert, & M. Skivenes (Eds.), International handbook on child protection systems. Oxford University Press.

- Hvinden, B. (2003). The uncertain convergence of disability policies in Western Europe. Social Policy and Administration, 37(6), 609–624. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9515.00361

- Jakobsen, S. E. (2018, February 10). Protests mount against Norwegian Child Welfare Service. Science Norway. https://sciencenorway.no/a/1453943

- Juhasz, I., & Skivenes, M. (2016). The population’s confidence in the child protection system – a survey study of England, Finland, Norway and the United States (California). Social Policy & Administration. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12226.

- Kriz, K. (2020). Protecting children, creating citizens. Policy Press. https://doi.org/10.1332/policypress/9781447355885.003.0001

- Legatum Institute. (2020). The Legatum Prosperity Index 2020: Overview. The Legatum Institute Foundation. https://docs.prosperity.com/3916/0568/0669/The_Legatum_Prosperity_Index_2020_Overview.pdf.

- Lohne, J.-L., Ede, R. T., Norman, M. G., & Åsebø, S. (2015, February 9). Tsjekkias president sammenligner norsk barnevern med nazi-program. VG. https://www.vg.no/i/o0zkK.

- Moody, O. (2018, December 18). Norwegian mother wins asylum in Poland. The Times. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/norwegian-mother-gets-asylum-in-poland-m9bzjnt85.

- Pösö, T., Skivenes, M., & Hestbæk, A. D. (2014). Child protection systems in the Danish, Finnish and Norwegian welfare states – time for a child centric approach? European Journal of Social Work, 17(4), 475–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2013.829802

- Richardson, D., Bruauf, Z., Toczydlowska, E., & Chzhen, Y. (2017). Comparing child-focused sustainable development goals (SDGs) in High-income countries: Indicator development and overview. (Innocenti Working Paper No. 2017-08). UNICEF Office of Research. https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/902-comparing-child-focused-sdgs-in-high-income-countries-indicator-development-and-overview.html

- Rothstein, B. (1998). Just institutions matter the moral and political logic of the universal welfare state. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511598449.

- Rothstein, B. (2009). Creating political legitimacy: Electoral democracy versus quality of government. American Behavioral Scientist, 53(3), 311–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764209338795

- Schapiro, T. (1999). What is a child? Ethics, 109(4), 715–738. https://doi.org/10.1086/233943

- Schomerus, G., Lucht, M., Holzinger, A., Matschinger, H., Carta, M. G., & Angermeyer, M. C. (2011). The stigma of alcohol dependence compared with other mental disorders: A review of population studies. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 46(2), 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agq089

- Sentio Research Norge. (2019, November). Befolkningenes holdninger til barnevernet. The Norwegian Directorate for Children, Youth and Family Affairs. https://bufdir.no/Bibliotek/Dokumentside/?docId=BUF00005134.

- Skivenes, M. (2011). Norway: Toward a child centric perspective. In N. Gilbert, N. Parton, & M. Skivenes (Eds.), Child protection systems: International trends and orientations (1st ed., pp. 154–179). Oxford University Press.

- Skivenes, M., Barn, R., Križ, K., & Pösö, T. (Eds.). (2015). Child welfare systems and migrant children: A cross country study of policies and practice. Oxford University Press.

- Skivenes, M. & Strandbu, A. (2006). A Child perspective and participation for children. Journal of Children, Youth and Environments, 16(2), 10–27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7721/chilyoutenvi.16.2.0010

- Skivenes, M. & Stenberg, S. (2013). Risk assessment and domestic violence – how do child welfare workers in three countries assess and substantiate the risk level of a 5-year-old girl? Child and Family Social Work, 20(4), 424–436. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/cfs.12092

- Skivenes, M., & Tefre, ØS. (2012). Adoption in the child welfare system—A cross-country analysis of child welfare workers’ recommendations for or against adoption. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(11), 2220–2228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.07.013

- Skivenes, M. & Thoburn, J. (2016). Pathways to permanence in England and Norway. A critical analysis of documents and data. Children and Youth Service Review, 67, 152–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.05.020

- Skivenes, M., & Thoburn, J. (2017). Citizens’ views in four jurisdictions on placement policies for maltreated children. Child & Family Social Work, 22(4), 1472–1479. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12369

- Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571. https://doi.org/10.2307/258788

- Sunstein, C. R., Reisch, L. A., & Rauber, J. (2018). A worldwide consensus on nudging? Not quite, but almost: Worldwide attitudes toward nudging. Regulation & Governance, 12(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12161

- Sutherland, E. (2017). Scotland: Proactive child protection: A step too far? In M. Brinig & F. Banda (Eds.), International survey of family law: 2017 edition (pp. 287–309). Jordans/Family Law. https://www.familylaw.co.uk/news_and_comment/the-international-survey-of-family-law-2017-edition.

- Svallfors, S. (1996). National differences in national identities? An introduction to the International Social Survey Programme. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 22(1), 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.1996.9976526

- Svallfors, S. (Ed.). (2012). Contested welfare states: Welfare attitudes in Europe and beyond (1st ed., Kindle ed.). Stanford University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvqsdrs4

- Todahl, J., Barkhurst, P. D., Watford, K., & Gau, J. M. (2020). Child abuse and neglect prevention: a survey of public opinion toward community-based change. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 14(3), 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2019.1612499

- Thoburn, J. (In press). Child welfare and child protection services in England. In J. D. Berrick, N. Gilbert, & M. Skivenes (Eds.), International handbook of child protection systems. Oxford University Press*.

- UNICEF Innocenti. (2020). Worlds of influence. understanding what shapes child well-being in rich countries (Innocenti Report Card 16). UNICEF Office of Research. https://www.unicef-irc.org/child-well-being-report-card-16.

- Valarino, I., Duvander, A.-Z., Haas, L., & Neyer, G. (2018). Exploring Leave Policy Preferences: A Comparison of Austria, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 25(1), 118–147. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxx020

- Whewell, T. (2018, August 3). Norway’s hidden scandal. BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-sh/norways_hidden_scandal.

- WHO. (2020). Alcohol use disorders (15+), 12 month prevalence (%) with 95%. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/alcohol-use-disorders-(15-)-12-month-prevalence-(-)-with-95-.

- Wilkinson, L. (2017, February 27). Norway’s government-abducted children, and ramifications for Europe. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/realspin/2017/02/27/norways-government-abducted-children-and-ramifications-for-europe/.

- World Justice Project. (2020). The World Justice Project. Rule of Law Index 2020. World Justice Project. http://ascelibrary.org/doi/10.1061/%28ASCE%291532-6748%282009%299%3A3%28129%29.

- Zelditch, M. (2004). Institutional effects on the stability of ogranisational authority. In C. Johnson (Ed.), Legitimacy processes in organizations (Vol. 22, pp. 25–48). Emerald Group Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0733-558X(04)22001-8.

- Zelditch, M., & Walker, H. A. (2003). The legitimacy of regimes. In S. R. Thye & J. Skvoretz (Eds.), Power and status (Vol. 20, pp. 217–249). Emerald Group Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0882-6145(03)20008-4.