ABSTRACT

Electronic information systems (EIS) are widely used in social work, but empirical research results about their use have yet to be disseminated and analysed. This scoping review of 36 articles published between 2000 and 2019 was conducted to summarise the existing body of knowledge to identify which themes have been the subject of previous research, as well as identifying gaps for future research. Four themes were identified: (1) the effects of using EISs on social work; (2) factors that have an impact on the use of EISs; (3) social workers’ strategies in the use of EISs and (4) the development of EISs with social workers. The findings show that the use of EISs changed the priorities of social work. However, social workers deviated from the rules of EISs to maintain their agency in relation to their work. The use of EISs’ lacked training, which led more to recording data instead of utilising it for professional purposes. Social workers’ participation in the development of EISs was seen essential to avoid unanticipated consequences. EISs are not limited to technical or usability challenges, but there are more profound issues that need further examination.

ABSTRAKTI

Sähköisiä tietojärjestelmiä käytetään laajasti sosiaalityössä, mutta empiirisiä tutkimustuloksia niiden käytöstä ei ole vielä analysoitu ja levitetty. Tässä kartoittavassa kirjallisuuskatsauksessa tarkasteltiin vuosien 2000–2019 julkaistun 36 tutkimusartikkelin tuloksia selvittäen, mitkä teemat korostuivat tutkimuksissa sekä millaisia tutkimusaukkoja oli tunnistettavissa. Analyysin perusteella tunnistettiin neljä pääteemaa: (1) tietojärjestelmien käytön vaikutukset sosiaalityöhön; (2) tekijät, joilla on vaikutusta tietojärjestelmien käytössä; (3) sosiaalityöntekijöiden toimintatavat tietojärjestelmien käytössä ja (4) tietojärjestelmien kehittäminen sosiaalityöntekijöiden kanssa. Tulosten mukaan tietojärjestelmien käyttö muutti sosiaalityön painopisteitä. Sosiaalityöntekijät kuitenkin poikkesivat tietojärjestelmän säännöistä ja vaatimuksista pystyäkseen säilyttämään toimijuutensa suhteessa tekemäänsä asiakastyöhön. Tietojärjestelmien käytön koulutus oli puutteellista, mikä johti tietojärjestelmien käyttöön lähinnä tiedon tallentamisen välineinä tiedon hyödyntämisen sijaan. Sosiaalityöntekijöiden osallistumista tietojärjestelmien kehittämiseen pidettiin olennaisena odottamattomien seurausten välttämiseksi. Tietojärjestelmien käyttö ei rajoitu teknisiin tai käytettävyyshaasteisiin, vaan syvällisempiin kysymyksiin, jotka vaativat jatkotutkimusta.

Introduction

Electronic information systems (EIS) are widely used in social work. They are essential for accessing, managing, and using client information (Fitch, Citation2019). However, they have also created more demands on professionals as well as changes in social work practice ‘from a narrative to a database way of thinking’ (Parton, Citation2009). In social work organisations many EISs have been implemented in a context in which there is a lack of agreement about what the system does, how it helps, and whether it is worth the resource expenditure (Carrilio, Citation2005). Governmental priorities for EIS use have fostered accountability, efficiency, transparency, and quality of services with many impacts on social work practices (e.g. Gillingham, Citation2011). The EISs have served more managerial needs than the needs of practitioners (Fitch, Citation2019; Gillingham, Citation2011; Munro, Citation2011). For example, Eileen Munro (Citation2011) has argued that while personal relationships play a central role in social work, they have been gradually stifled and replaced by the managerialist logic of EISs. Other scholars have pointed out that social workers’ discretion has diminished with the introduction of EISs. According to Parton and Kirk (Citation2010), social workers feel they are not able to determine what information is relevant because the required information is predefined in the structures of the EISs.

Although plenty of research on EIS use in social work has already been carried out, few if any efforts have been made to summarise the empirical evidence and assess earlier findings. To the best of my knowledge, this study presents the first scoping review on the use of EISs in the context of social work. This scoping review summarises the existing body of knowledge to identify which themes have been the subject of previous research, as well as identifying gaps for future research. The review was guided by the following research questions: (1) What are the key themes studied in previous research articles? (2) What are the main findings of these studies?

There is a great need for a scoping review of the current state of EIS research in social work because of the ongoing renewal and development of EISs across countries. In the European Union, this renewal is tightly coupled with the strategies aiming to promote the digitalisation of social services delivery (Eurofound, Citation2020). In general, the starting point for the development of EIS must be a strong understanding of users’ needs, tasks, and operating environment (Martikainen et al., Citation2020). This scoping review produces knowledge that helps policymakers to make more informed decisions on the renewal of EISs. Moreover, the article caters to the needs of social work organisations in their efforts to better recognise the needs and challenges social workers encounter while using EISs. Lastly, the results can support EIS vendors in developing their products to be more user-friendly and better fit for social work.

Methodology

A scoping review is a method of mapping relevant literature in the field of interest (Arksey & O'Malley, Citation2015). It is guided by a requirement to identify all relevant literature regardless of study design and is less likely to seek to address very specific research questions nor aim to assess the quality of the included studies (Arksey & O'Malley, Citation2015, p. 22). The initial idea is to scope a body of literature, identify knowledge gaps and for example, to investigate research conduct (Munn et al., Citation2018). The information obtained in a review is important to acquiring an understanding of a topic, what has already been done on it, how it has been researched, and what its key themes are (Hart, Citation1998). When they are compared to systematic reviews, scoping review can be undertaken as standalone projects, especially where an area is complex or has not been reviewed comprehensively before (Mays et al., Citation2001).

This review follows Arksey and O'Malley (Citation2015) framework for conducting a scoping review consisting of five steps: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data and (5) collating, summarising, and reporting the results. After the research question was identified and defined, test searches for different databases were done. This helped to determine the appropriate search terms as well as inclusion and exclusion criteria. Test searches revealed that using only the terms ‘information systems’ and ‘social work’ would exclude many relevant articles, so search terms were chosen more broadly.

The final search was conducted in the following databases: Scopus, using article title, abstracts and keywords and ProQuest (Social Services Abstracts and Sociological Abstracts) using anywhere except full text. The initial idea was to focus on social scientific articles. Regarding Scopus, however, the scope of review was expanded to the articles that were published in the field of computer science, because in test searches relevant articles surfaced. The applied search terms were: ‘information systems’ OR ‘information technology’ OR ICT AND ‘social work’ OR ‘social services’ OR ‘social care’ OR ‘social welfare’ OR ‘human services’.

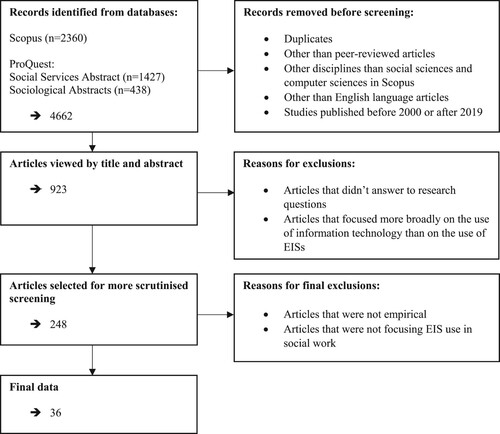

The search for the databases yielded 4662 items. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to reduce the number of articles. The inclusion criteria were that articles had been peer-reviewed and published in English in scholarly journals between January 2000 to December 2019. In Scopus, other disciplines than social sciences and computer sciences were excluded. After these limitations and excluded duplicates, the result was 923 articles. The articles were viewed by title and abstract and more articles were excluded. After excluding articles that did not answer the research question or focused more broadly on the use of information technology than on the use of EISs, a total of 248 articles remained left. The remaining articles were re-evaluated for their titles, abstracts, findings, and discussions, taking into account the inclusion and exclusion criteria. After this, a further 212 articles were excluded. Articles were excluded mainly because they were not empirical or were not focused on the use of EISs in social work. Finally, a total of 36 articles were included, all of which were accessible to the researcher. The process of the scoping review is presented in .

Arksey and O'Malley (Citation2005, p. 27) state that a scoping review requires an analytic framework or thematic construction to present a narrative account of existing literature. In this review, a qualitative content analysis was adopted for summarising and synthesising the characteristics of articles (Creswell, Citation2007). Articles were carefully viewed and the keycodes were identified. Codes were written next to each article that was placed in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. A colour-coding system was used to look for similarities and differences of the articles and after that four main themes were identified. The themes were named, and articles were divided under each theme. Some of the articles are incorporated into several themes.

Findings

In this section, the findings of the scoping review are presented. First, a descriptive overview of the included articles is presented. Second, the findings of the content analysis are presented under four themes: (1) the effects of using EISs on social work; (2) factors that have an impact on the use of EISs; (3) social workers’ strategies in the use of EISs and (4) the development of EISs with social workers.

Descriptive overview of the included articles

The following information was retrieved from the articles: author and year of study, country of study, aim of study, methods and sample of study and the identified themes. provides a detailed description of the included articles (n = 36).

Table 1. Description of included articles.

The reviewed articles were published in 17 peer-reviewed journals, having the highest number in the British Journal of Social Work (n = 11). Articles were published between 2006 and 2019, with peaks in 2014 (n = 8) and 2015 (n = 7). Most of the articles were conducted in Australia (n = 12) and Belgium (n = 8), followed by UK (n = 7), cross-national (n = 3), Finland (n = 2), USA (n = 2), Sweden (n = 1) and Israel (n = 1).

The findings are presented as the assumption that EISs are the same in every article. However, they may have some differences between countries and organisations for example how they are constructed or in what social services they are used. Many of these EISs are so-called complex systems, like the system called Integrated Children’s System in child welfare services in the UK (see Pithouse et al., Citation2012; Sarwar & Harris, Citation2019; Shaw et al., Citation2009; Wastell et al., Citation2010; Wastell & White, Citation2014; White et al., Citation2010). Some articles were focusing more on a risk assessment tool inside EIS (Pithouse et al., Citation2012), decision-making tools (Gillingham, Citation2013) or e-tools for assessment, care planning and review (Hill, Citation2014).

Most of the articles were qualitative studies (n = 34), in which interviews, but also observations and field diaries, as well as documentary data were used. It is noteworthy that many of these are conducted by the same authors, a fact which needs to be considered when reviewing the findings. Fourteen articles were written by Philip Gillingham from Australia. He has studied social work and EIS for many years in many social work organisations mainly in Australia, but also in England, New Zealand, and Scotland. Six articles are conducted by Jochen Devlieghere and his colleagues, whose studies were conducted in Flanders, the Dutch-speaking region of Belgium, where a new EIS in the field of child welfare and protection was implemented. The same data were also used in De Corte et al. (Citation2019). Also, three articles that are conducted in the UK are including the same authors (Wastell et al., Citation2010; Wastell & White, Citation2014; White et al., Citation2010) concentrating to the challenges that the new EIS has brought to the practice.

Two articles were quantitative. Carrilio (Citation2007) used a survey containing 44 questions about attitudes, skills, and experience with information systems. Savaya et al. (Citation2006) used the instrument that was designed to assess the practitioners’ use of IT to perform relevant organisational functions. In addition, Shaw et al. (Citation2009) used a mixed-method approach consisting of focus group interviews, surveys, statistical analyses of the system of over 10,000 records, interviews, and various documents. It may be important to note that quantitative and qualitative studies are equally represented in the references.

The use of EIS on social work – themes arising from the content analysis

The effects of using EISs on social work

Most of the articles (n = 30) reported the effects of using an EIS on social work (see ). The implementation of EISs has been the result of political goals to achieve more transparent and responsive social work (Devlieghere et al., Citation2016; Gillingham & Graham, Citation2016; Hill, Citation2014; Pithouse et al., Citation2012; Wastell et al., Citation2010; Wastell & White, Citation2014; White et al., Citation2010). However, these goals have not always been achieved in practice. For example, Devlieghere et al. (Citation2016), who examined experiences of 18 policy actors about the implementation of new EIS in Belgium, found that although the EIS was believed to increase efficiency, enhance transparency, and cut the costs of public spending, it remained unclear how these demands might be achieved. In another article Devlieghere and Roose (Citation2019) noticed that the mandatory use of EISs resulted in a lack of transparency in social work. According to interviews with social workers and managers, it was found out that there was a difficulty to capture the necessary nuances that help to create a transparent overview of the service user’s trajectory with the use of EIS (Devlieghere & Roose, Citation2019).

As the political goal was to create transparency for the delivered services and decisions, the documentation of the system became important. However, this was also challenging with the use of EISs (Burton & van den Broek, Citation2009; Devlieghere & Roose, Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Citation2019; Gillingham, Citation2013, Citation2014d; Hill, Citation2014; Huuskonen & Vakkari, Citation2015; Lagsten & Andersson, Citation2018; Pithouse et al., Citation2012; Wastell & White, Citation2014). For instance, Pithouse et al. (Citation2012), who examined a risk assessment tool used in the EIS (Integrated Children’s System) in England and Wales, found that it proved to be time-consuming and had limited the recording of practitioners’ observations of the client situations. The narrative tradition of social work was diminished, which made it difficult to get an overall picture of the client (Pithouse et al., Citation2012). Similarly, White et al. (Citation2010), who also examined the Integrated Children’s System, found that the data were recorded on complex forms, that were cast as unwieldy, repetitive, and difficult to complete and to read, and their lack of practical utility was even more apparent concerning engaging service users in family support or child protection plans. Also, Gillingham (Citation2013) who has studied the use of EISs in many social work organisations, found that structures failed to account for the complexity and diversity of the situations of clients, leading to the confusion and frustration of practitioners.

Articles carried out in the Nordic countries also found challenges in documenting. For instance, Huuskonen and Vakkari (Citation2015) found that social workers (n = 23) and managers (n = 7) in child welfare organisations in Finland did not always know what should be recorded and there were information gaps in long-term client relationships. They also mentioned that the EIS were unable to show all the nuances and sensations important in gaining an overall picture of a client (Huuskonen & Vakkari, Citation2015). Similarly, Lagsten and Andersson (Citation2018) who reported findings covering a nine-year longitudinal study on critical issues in the use of a case management system in a Swedish social work agency, found that social workers were recording data incorrectly, they did not know what needed to be recorded and who was responsible for making changes to the EIS.

The formalities required by the EIS became more important than the content of the work itself (Burton & van den Broek, Citation2009; Gillingham, Citation2014d, Citation2015c, Citation2016; Koskinen, Citation2014; Lagsten & Andersson, Citation2018; Sarwar & Harris, Citation2019; Smith & Eaton, Citation2014). For instance, Smith and Eaton (Citation2014), who interviewed 386 child protection managers and practitioners in the state of California found that traditional face-to-face interactional activity with clients had changed to a more automatic, information-driven work activity. This caused a lot of resistance and frustration among practitioners (Smith & Eaton, Citation2014). Gillingham (Citation2014d) also illustrated that in both Australia and England social workers’ expectations about their work roles were reconfigured by the demands of EIS. Similarly, in England Sarwar and Harris (Citation2019) discovered how the EIS was instructing professionals to select and click on boxes based on which tasks should be performed, diminishing the discretion of social workers. Also, Koskinen (Citation2014) stated in her Finnish study, based on seven interviews of social workers, that the EIS had been given the power that previously belonged to social workers.

Factors that have an impact on the use of EISs

Six articles examined the factors that had an impact on the use of EISs (see ). For instance, Lagsten and Andersson (Citation2018), Huuskonen and Vakkari (Citation2015) and Savaya et al. (Citation2006) all found that social workers lacked training to use the system. Lagsten and Andersson (Citation2018) found that there was the unclear perception and distribution of responsibilities between IT support and managers, which might result to the lack of training.

The lack of training resulted, for instance, in the inability to utilise the information. Savaya et al. (Citation2006) showed, based on a questionnaire of 136 social workers in Israel, that social workers were not accustomed to utilising the data they enter from systems to support their work. Therefore, it was preferred to store data in EISs, but data were not desired and able to be used for reports or evaluations (Savaya et al., Citation2006). Carrilio (Citation2007) also demonstrated that the importance of social workers’ skills and experience with using computers with the utilisation of EISs is apparent. Based on the answers of 245 school social workers in the USA, Carrilio concluded that organisations should focus on enhancing practitioners’ computer skills as well as assuring that the information is easy to use and perceived as useful by them to increase practitioners’ utilisation of EIS.

Interestingly, social workers’ attitudes towards the system had no strong influence on its utilisation (Carrilio, Citation2007). He proposed that the reason for this was the number of younger social workers in the fieldwork, who were more comfortable with computers. However, Gillingham (Citation2014a) noted that more experienced practitioners who were not so familiar with technology were able to make many constructive suggestions for changes to the EIS user interface and functionality to serve their purposes efficiently. Based on this, the age does not seem to correlate with the attitude.

Several researchers concluded that organisations need to pay careful attention to training for the use of EISs (Gillingham, Citation2018b; Lagsten & Andersson, Citation2018; Savaya et al., Citation2006). Training organised at the agency has an important role in the development of practitioners’ skills and for better utilisation of the system (Savaya et al., Citation2006).

Social workers’ strategies in the use of EISs

Eleven articles examined the strategies of social workers in the use of EISs (see ). EIS use was experienced to be complicated and time-consuming, and the needs of day-to-day work were not understood (e.g. De Corte et al., Citation2019; De Witte et al., Citation2016; Koskinen, Citation2014; Shaw et al., Citation2009), which led professionals to use various strategies to deviate from the rules and procedures of the EISs. In this way, they maintained their agency to the use of EISs.

De Corte et al. (Citation2019), De Witte et al. (Citation2016), Hill (Citation2014), Huuskonen and Vakkari (Citation2015), Pithouse et al. (Citation2012) and White et al. (Citation2010) found that social workers used strategic and moral decisions when using an EIS to be able to retain a narrative and relational approach of practice, which they valuated important. For instance, White et al. (Citation2010), who evaluated EIS use in England and Wales, found that social workers were not able to fully describe the relationships the children have with each other or their parents. The EIS lacked support for recording data for multiple children in the family, which results in data either being copied across automatically or ‘copied and pasted’ into different fields (White et al., Citation2010, p. 411). In Belgium, De Witte et al. (Citation2016) demonstrated that social workers wanted to preserve a relational and narrative work approach that the EIS failed to support. To follow the cases of clients, they retained, for example, paper files. These strategies not only resulted in a gap between ICT policy and the execution of that policy in practice but also decreased the extent to which accountability can be realised via the registration of data (De Witte et al., Citation2016). Similarly, Hill (Citation2014) and Huuskonen and Vakkari (Citation2015) found that social workers kept paper notes in addition to completing the forms that EISs included because they did not want to lose some of the narratives they had been recording.

In Belgium, De Corte et al. (Citation2019) examined how social workers use their agency when implementing top-down policy measures as street-level bureaucrats. They found that after the implementation of an EIS both managers (n = 30) and social workers (n = 15) started to develop strategies of resistance to deviating from policy regulations and procedures. Moreover, it was shown how social workers were still aware of the institutional context in which they operated but equally maintained a strong commitment to disengage from this context and act to change it (De Corte et al., Citation2019).

White et al. (Citation2010) found that the rigidity of the EIS made practitioners circumvent operations or record data in the wrong places. Social workers reported difficulty in recording ‘a decent social history’ about the family, often alluding to a more meaningful account carried ‘in their heads’ (White et al., Citation2010, p. 411). In addition, Savaya et al. (Citation2006) found that the EIS was used more for data entry instead of utilising data. There was a preference to enter data into EISs, but it was not desired or able to be used for reports or evaluations of the clients’ situations. The evaluation of the effectiveness of the work was made without the support of an EIS rather than with it (Savaya et al., Citation2006, pp. 212–213).

The development of EISs with social workers

The development of EISs with social workers was examined in 16 articles (see ). Articles emphasised that end-user participation in the development of EISs is essential, to avoid unanticipated consequences. Most of these articles were conducted by Gillingham.

Gillingham (Citation2014a) found during the testing phase of the EIS that social workers were able to make many constructive suggestions for changes to its user interface and functionality so that it might serve their purposes more efficiently. He also stated that it is important to involve different kinds of users (e.g. occasional users, novice users) in the development of EISs because they have diverse knowledge and various skills in using systems. However, it was found that some social workers struggled to express their needs to the designers (Citation2015d). Similarly, Lagsten and Andersson (Citation2018) found that there was a lack of language and structures for describing social work content to the designers, which made critical discussions for improvement difficult. The authors argued that there should be clear terminology for interpersonal understanding between IT designers and social workers (Lagsten & Andersson, Citation2018).

In the UK, both Hill (Citation2014) and Wastell and White (Citation2014) stated the importance of concentrating on the work environments and the needs of social workers instead of on traditional technology-based approaches. Hill (Citation2014) was focusing on the assessment and planning tools inside the EIS, which intention was to provide support for the practitioners, rather than intending to generate major process change. However, the opposite happened. She highlighted how new structures cannot simply be planned and delivered as envisaged, but emerge from the articulation of new rules, the accessibility and alignment of resources that support them, the modalities employed in their development and delivery and the interactions that are enabled, or disabled, by the approach to the implementation of the change. (Hill, Citation2014) Wastell and White (Citation2014) provided a cameo example of the sociotechnical approach in action, showing how imaginative users can be when they are given the opportunity to participate in the designing tools for social work. As Gillingham (Citation2015b) stated, social workers must make a significant contribution to, and increasingly take the lead in the design of technology that will shape, guide, and ultimately support their practice.

Discussion

This scoping review mapped the literature available on a topic concerning EIS use in social work by identifying the key themes and the main findings of these studies. The study highlights the social impact of technological change and the tensions and contradictions it creates. With the help of the review, the challenges related to the use and changes of EISs can be met, while renewing EISs in social work.

The effects of using EIS on social work had been studied the most. EISs have been criticised for failing to meet the needs of social work and have therefore not been integrated into the practice. The findings show that a significant amount of time was spent recording and storing information in the EISs instead of spending time with clients. The EISs failed to account for the complexity and diversity of the situations of clients, leading to the frustration and confusion of practitioners. This also influenced social workers’ feeling their discretion narrowed because they were not able to do tasks that they found important. The findings of this scoping review thus support previous academic discussion that has raised concerns about the compatibility of EISs and social work (e.g. Munro, Citation2011; Parton & Kirk, Citation2010).

However, some studies found that social workers started to use strategies to deviate from the rules and procedures in EIS and thus maintained their agency to its use to be able to do the work they valued important. For instance, in social work the narratives have played a big role and EISs have made it difficult to perceive the overall picture of the client. This led social workers to retain paper files and notes about their clients to keep all the necessary information. More attention should be paid to the content of social work to understand the essentialities of practice and align those needs with technology.

Articles looking at factors that have an impact on the use of EISs highlighted training as the most important factor. Lack of training resulted in the inability to utilise information and led only to recording and storing data into the system. However, this theme was in a minor of this review and needs further examination to find out if there are other factors that have an impact on the use of EISs.

Finally, the development of EISs with social workers was studied. The findings of these articles support theoretical research to participate end-users in the design process of EISs (Fitch, Citation2019; Gillingham, Citation2021) to avoid unanticipated consequences. Articles pointed out that focusing on users and the social and cultural environment rather than a technological approach will likely produce more suitable systems for social work. On the other hand, challenges were identified in finding a common language and describing needs to IT designers. The clarification of concepts is thus a clear need for successful co-development. Articles highlighted the idea of guiding social workers as they engage in participatory design processes. Further research needs to identify the benefits of user-driven systems in social work. It should also be noted that none of the articles looked at client experiences concerning the EISs, although strengthening client involvement plays a significant role in the digitisation of services (Eurofound, Citation2020). This needs further attention.

Based on this review, the experiences of those who use EISs in social work are critical, and lessons should be learned from these experiences when developing systems. EISs are not limited to technical or usability challenges, but there are more profound issues. Technology has taken on a big role in social work, changing work priorities. One might even ask who controls social work: technology, or the professional and ethical commitments of social work? This review shows that the role of EISs in social work is problematic and needs further examination.

Limitations

This review was limited to articles published in English between 2000 and 2019, possibly excluding most recent publications and articles written in other languages. Many of the reported studies were conducted by the same authors. It affected the themes identified. Although there seems to be a lot of research in this area, the geographical representation of the existing literature remains narrow. Also, previous research on the use of EISs has mainly focused on the field of child welfare. For this reason, the importance of further research that is more widespread is needed. The samples of the qualitative articles were rather small, which diminishes the generalisability of findings. Finally, because this was a scoping review, included articles were not subjected to a quality appraisal. However, this review offers the first effort to bring the relevant articles together and gives a deeper understanding of the topics that need to be considered in developing EIS for social work.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledge her supervisors, professor Marjo Kuronen and associate professor Sakari Taipale, for the tremendous help and encouraging comments and discussions. The author would also thank Hanna Mikkonen, doctoral student of Cognitive Science at the University of Jyvaskyla, who gave her important comments from the information system science point of view. The author is also grateful to those people, who helped her with the use of English.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Katri Ylönen

Katri Ylönen, (Lic.Soc.Sc) is doctoral student in the Department of Social Sciences and Philosophy at the University of Jyväskylä, Finland. Her research focuses on social workers’ experiences of information systems as part of client work. Katri has extensive experience in digitising social work, most recently serving as a project manager in the project Social and Health Care Client and Patient Information System (CPIS) in the Central Finland Hospital District. She has previously studied interactive online support for young people.

References

- Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Burton, J., & van den Broek, D. (2009). Accountable and countable: Information management systems and the bureaucratization of social work. British Journal of Social Work, 39(7), 1326–1342. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcn027

- Carrilio, T. (2005). Management information systems: Why are they underutilized in the social services? Administration in Social Work, 29(2), 43–61. https://doi.org/10.1300/J147v29n02_04

- Carrilio, T. (2007). Using client information systems in practice settings: Factors affecting social workers’ use of information systems. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 25(4), 41–62. https://doi.org/10.1300/J017v25n04_03

- Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among the five approaches (2nd ed). Sage Publications.

- De Corte, J., Devlieghere, J., Roets, G., & Roose, R. (2019). Top-down policy implementation and social workers as institutional entrepreneurs: The case of an electronic information system in Belgium. British Journal of Social Work, 49(5), 1317–1332. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcy094

- De Witte, J., Declercq, A., & Hermans, K. (2016). Street-level strategies of child welfare social workers in Flanders: The use of electronic client records in practice. British Journal of Social Work, 46(5), 1249–1265. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcv076

- Devlieghere, J., Bradt, L., & Roose, R. (2016). Policy rationales for Electronic Information Systems: An area of ambiguity. British Journal of Social Work, 47(5), 1500–1516. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcw097

- Devlieghere, J., Bradt, L., & Roose, R. (2017). Governmental rationales for installing Electronic Information Systems: A quest for responsive social work. Social Policy & Administration, 51(7), 1488–1504. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12269

- Devlieghere, J., Bradt, L., & Roose, R. (2019). Electronic information systems as means for accountability: Why there is no such thing as objectivity. European Journal of Social Work. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2019.1585335

- Devlieghere, J., & Roose, R. (2018a). Electronic Information Systems: in search of responsive social work. Journal of Social Work, 18(6), 650–665. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017318757296

- Devlieghere, J., & Roose, R. (2018b). Creating transparency through Electronic Information Systems: Opportunities and pitfalls. The British Journal of Social Work, 48(3), 734–750. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcx052

- Devlieghere, J., & Roose, R. (2019). Documenting practices in human service organisations through information systems: When the quest for visibility ends in darkness. Social Inclusion, 7(1), 207–217. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v7i1.1833

- Eurofound. (2020). Impact of digitalisation on social services, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/report/2020/impact-of-digitalisation-on-social-services.

- Fitch, D. (2019). Using data to improve client services. In L. Goldking, L. Wolf, & P. Freddolino (Eds.), Digital social work. Tools for practice with individuals, organizations, and communities, 109–125. Oxford University Press.

- Gillingham, P. (2011). Computer-based information systems and human service organisations: Emerging problems and future possibilities. Australian Social Work, 64(3), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2010.524705

- Gillingham, P. (2013). The development of electronic information systems for the future: Practitioners, ‘embodied structures’ and ‘technologies-in-practice’. British Journal of Social Work, 43(3), 430–445. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcr202

- Gillingham, P. (2014a). Electronic Information Systems and social work: Who are we designing for? Practice: Social Work in Action, 26(5), 313–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2014.958454

- Gillingham, P. (2014b). Information Systems and Human Service Organizations: managing and designing for the “occasional user. Human Service Organizations Management, Leadership & Governance, 38(2), 169–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/03643107.2013.859198

- Gillingham, P. (2014c). Repositioning Electronic Information Systems in Human Service Organizations. Human Service Organizations Management, Leadership & Governance, 38(2), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/03643107.2013.853011

- Gillingham, P. (2014d). Technology configuring the user: Implications for the redesign of Electronic Information Systems in social work. British Journal of Social Work, 46(2), 323–338. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcu141

- Gillingham, P. (2015a). Electronic Information Systems and Human Service Organizations: the needs of managers. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 40(1), 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2015.1069232

- Gillingham, P. (2015b). Electronic information systems and social work: Principles of participatory design for social workers. Advances in Social Work, 16(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.18060/18244

- Gillingham, P. (2015c). Electronic Information Systems and Human Service Organizations: The unanticipated consequences of organizational change. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 39(2), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2014.987412

- Gillingham, P. (2015d). Implementing Electronic Information Systems in Human Service organisations: The challenge of categorisation. Practice: Social Work in Action, 27(3), 163–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2015.1014334

- Gillingham, P. (2015e). Electronic information systems in human service organisations: The what, who, why and how of information. British Journal of Social Work, 45(5), 1598–1613. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcu030

- Gillingham, P. (2016). Electronic Information Systems to guide social work practice: The perspectives of practitioners as end users. Practice: Social Work in Action, 28(5), 357–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2015.1135895

- Gillingham, P. (2018a). Decision making about the adoption of digital technology in human service organizations: Some key considerations. European Journal of Social Work, 21(4), 521–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2017.1297773

- Gillingham, P. (2018b). From bureaucracy to technocracy in a social welfare agency: A cautionary tale. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development, 29(2), 108–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/02185385.2018.1523023

- Gillingham, P. (2021). Practitioner perspectives on the implementation of an electronic information system to enforce practice standards in England. European Journal of Social Work, 24(5), 761–771. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2020.1870213

- Gillingham, P., & Graham, T. (2016). Designing electronic information systems for the future: Social workers and the challenge of New Public Management. Critical Social Policy, 36(2), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018315620867

- Hart, C. (1998). Doing a literature review: Releasing the social science research imagination. Sage Publications.

- Hill, P. (2014). Supporting personalisation: The challenges in translating the expectations of national policy into developments in local services and their underpinning information systems. Social Policy & Society, 13(4), 593–607. https://doi.org/10.1017/S147474641400013X

- Huuskonen, S., & Vakkari, P. (2015). Selective clients’ trajectories in case files: Filtering out information in the recording process in child protection. British Journal of Social Work, 45(3), 792–808. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bct160

- Koskinen, R. (2014). One step further from detected contradictions in a child welfare unit—a constructive approach to communicate the needs of social work when implementing ICT in social services. European Journal of Social Work, 17(2), 266–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2013.802663

- Lagsten, J., & Andersson, A. (2018). Use of information systems in social work – challenges and an agenda for future research. European Journal of Social Work, 21(6), 850–862. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2018.1423554

- Martikainen, S., Salovaara, S., Ylönen, K., Tynkkynen, E., Kaipio, J., Tyllinen, M., & Lääveri, T. (2020). Sosiaalialan ammattilaiset halukkaita osallistumaan asiakastietojärjestelmien kehittämiseen – osallistumistavoissa kehitettävää. [Social professionals willing to participate in the development of CISs – the ways of participation needs development]. Finnish Journal of EHealth and Welfare, 12(3), 270–285. https://doi.org/10.23996/fjhw.96084

- Mays, N., Roberts, E., & Popay, J. (2001). Synthesising research evidence. In N. Fulop, P. Allen, A. Clarke, & N. Black (Eds.), Studying the organisation and delivery of health services: Research methods (pp. 188–220). Routledge.

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(143), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- Munro, E. (2011). The Munro review of child protection: Final report: A child centred system. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attach-ment_data/file/175391/Munro-Review.pdf.

- Parton, N. (2009). Challenges to practice and knowledge in child welfare social work: From the ‘social’ to the ‘informational’? Children and Youth Services Review, 31(7), 715–721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.01.008

- Parton, N., & Kirk, S. (2010). The nature and purposes of social work. In I. Shaw, K. Briar-Lawson, & J. Orme (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of social work research (pp. 23–36). SAGE Publications.

- Pithouse, A., Broadhurst, K., Hall, C., Peckover, S., Wastell, D., & & White, S. (2012). Trust, risk and the (mis)management of contingency and discretion through new information technologies in children's services. Journal of Social Work, 12(2), 158–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017310382151

- Sarwar, A., & Harris, M. (2019). Children’s services in the age of information technology: What matters most to frontline professionals. Journal of Social Work, 19(6), 699–718. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017318788194

- Savaya, R., Monnickendam, M., & Waysman, M. (2006). Extent and type of worker utilization of an integrated information system in a human service agency. Evaluation and Program Planning, 29(3), 209–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2006.03.001

- Shaw, I., Bell, M., Sinclair, I., Sloper, P., Mitchell, W., Dyson, P., Clayden, J., & Rafferty, J. (2009). An exemplary scheme? An evaluation of the integrated children's system. British Journal of Social Work, 39(4), 613–626. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcp040

- Smith, R. J., & Eaton, T. (2014). Information and communication technology in child welfare: The need for culture-centred computing. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 41(1), 137–160. Available at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw/vol41/iss1/8

- Wastell, D., & White, S. (2014). Making sense of complex electronic records: Socio-technical design in social care. Applied Ergonomics, 45(2), 143–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2013.02.002

- Wastell, D., White, S., Broadhurst, K., Peckover, S., & Pithouse, A. (2010). Children's services in the iron cage of performance management: Street-level bureaucracy and the spectre of Svejkism. International Journal of Social Welfare, 19(3), 310–320. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2009.00716.x

- White, S., Wastell, D., Broadhurst, K., & Hall, C. (2010). When policy o’erleaps itself: The “tragic tale” of the integrated children’s system. Critical Social Policy, 30(3), 405–429. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018310367675