ABSTRACT

There is a pressing need in the Nordic countries for evidence-based programmes for young children who have experienced early adversity. One such programme, Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up (ABC) was implemented in seven Norwegian child welfare services (CWS). The aim of this study was to interview families, CWS workers and their leaders to explore their experiences in implementing ABC and to make recommendations for future use. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 10 parents, 11 parent coaches and eight CWS leaders. Data were analysed using the framework method. The findings showed that ABC’s core elements such as in-vivo commenting and video feedback, were considered important for bringing about change. The intervention’s strengths-based approach helped reduce parents’ resistance towards coaches and strengthen the therapeutic relationship. There were diverging perspectives regarding the duration of the intervention, though most agreed on the need to make adaptations to suit the needs of individual families. Coaches viewed ABC as a welcoming addition to their service, due to the lack of interventions for infants in the CWS, although an expanded age limit would enable the recruitment of more families. Recommendations for future implementation include addressing recruitment and how to address issues outside the scope of ABC sessions.

ABSTRAKT

«Det er et stort behov i Norden for evidensbaserte programmer for barn som har opplevd motgang tidlig i livet. Et slikt program, Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up (ABC) ble implementert i sju norske barneverntjenester. Målet med denne studien var å intervjue familier, veiledere og ledere i barnevernet om deres erfaringer med å implementere ABC, for dermed å komme med anbefalinger for fremtidig bruk. Semistrukturerte intervjuer ble gjennomført med 10 foreldre, 11 veiledere og åtte ledere. Data ble analysert ved hjelp av «the framework method». Funnene viste at ABCs kjerneelementer, som in vivo-kommentering og videotilbakemelding, ble vurdert som viktige for å få til endring. Programmets styrkebaserte tilnærming bidro til å redusere foreldres motstand mot veilederne og å styrke den terapeutiske relasjonen. Det var ulike synspunkter rundt varigheten av programmet, selv om de fleste var enige om behovet for å gjøre tilpasninger til individuelle familier. Veilederne opplevde ABC som et nyttig tillegg i sin tjeneste, spesielt på grunn av mangelen på evidensbaserte tiltak for små barn i barnevernet. Likevel mente de også at en utvidet aldersgrense ville gjøre det mulig å rekruttere flere familier. Fremtidig implementering bør ta hensyn til utfordringer med rekruttering og hvordan man kan løse problemer som faller utenfor ABCs målområde.»

Introduction

The main purpose of Norwegian child welfare services (CWS) is to help children who live in conditions that can have an adverse impact on their lives (The Child Welfare Act, Citation1992), providing services like prevention, home-based assistance and out-of-home placement. Young children tend to be most at risk of maltreatment (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Citation2017) and vulnerable to maltreatment sequalae, in part because they are not able to report the violations they experience and thus unable to prevent events from recurring (Chu & Lieberman, Citation2010). Early intervention is necessary to prevent long-term negative consequences on children’s mental and physical development (Cicchetti et al., Citation2006) and out-of-home placements. Several evidence-based programmes (EBPs) exist for children who have experienced early adversity (Altafim & Linhares, Citation2016; Gubbels et al., Citation2019).

One such programme is Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up (ABC; Dozier & Bernard, Citation2019). ABC is a 10-session manualised intervention designed to promote healthy relationships between caregivers and children through weekly home visits. Two versions exist, ABC-Infant (ABC-I) for children aged 6–24 months and ABC-Toddler (ABC-T) for 24–48 months. The main goals of ABC-I are: first, to improve parental nurturing behaviour (i.e. providing sensitive care in response to children’s distress); second, help parents follow the child’s lead (i.e. responding contingently to the child’s signals); and third, reduce frightening parent behaviour (i.e. behaviour that is overwhelming or scary to the child). ABC has a sound evidence base from multiple randomised trials in CWS, foster care and international adoption (Dozier & Bernard, Citation2019). Compared with controls, ABC has shown improvements in parental sensitivity (Perrone et al., Citation2021), secure and organised attachment (Bernard et al., Citation2012), enhanced executive functioning (Lind et al., Citation2017) and diurnal cortisol levels (Garnett et al., Citation2020).

Despite the existence of ABC and other EBPs, few are used in the Norwegian CWS system. More than 30.000 support services are provided every year, and only about 2.5% of these can be labelled evidence-based (Christiansen et al., Citation2015). Moreover, most EBPs for young children have a limited evidence base or are based on studies conducted outside the Nordic countries (Eng et al., Citation2018). In other words, there is a pressing need for EBPs for the youngest children in Norwegian CWSs, as well as research conducted on these programmes in Norway. However, an important challenge with EBPs is that, despite their effectiveness in carefully designed trials, they often fail to reproduce the effect in less controlled settings (Embry & Biglan, Citation2008). One explanation for this is ‘Type III error’ – difficulty finding the effect of an intervention due to poor design or implementation (Dobson & Cook, Citation1980).

Feasibility studies are a potential solution to avoid Type III errors. The main goals of a feasibility study may include exploring the willingness of clinicians to recruit participants, willingness of participants to be recruited, whether the intervention can be delivered as intended, as well as other potential barriers or facilitators for successful implementation (Abbott, Citation2014). This can be used to determine whether a larger trial is viable and could help guide the future implementation process to avoid potential pitfalls and barriers. Another important consideration is to examine different levels involved in the implementation process, not just the individual directly affected by the intervention (Ferlie & Shortell, Citation2001). For instance, positive leadership and practitioner views of the intervention may be just as important for successful implementation as other implementation aspects (Egeland et al., Citation2019).

Aim of the study

The aim of the present study was to interview families, CWS workers and their leaders, all of whom were part of a pre–post feasibility study, to explore their experiences in implementing ABC-I in Norwegian CWS services and to make recommendations for adapting the programme for future use.

Methods

This qualitative study used semi-structured interviews to collect data from parents, CWS workers and CWS leaders on their experiences with ABC-I. Individual interviews allowed participants to share their experiences while providing rich, in-depth reflections from their experiences with ABC. The study was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (project nr.: 56433). Written consent was obtained before interviews.

Participants

Informants consisted of three groups: parents involved with the CWS who received ABC, parent coaches who provided ABC, and their respective leaders. This form of data triangulation is a way of providing multiple forms of evidence to enhance the validity of the data through corroboration across informant groups (Creswell & Miller, Citation2000). Of 29 parents in the feasibility study, 10 were interviewed (see ). There were 11 coaches employed at seven different CWSs in Eastern and Southern Norway, all of whom were interviewed. Eight CWS leaders were interviewed, representing seven CWSs. Two leaders represented the same service, as one changed workplace and was replaced by another.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics for interviewees.

Recruitment

Informants were recruited for a feasibility study of the ABC-I intervention in CWSs in Eastern and Southern Norway. Training started in February 2018 and 10 parent coaches were certified during 2019. Coaches received supervision from Norwegian fidelity-supervisors who had been trained by the ABC-team at the University of Delaware. Different sampling approaches were utilised to ensure a sample that was best suited to answer the research question and to provide rich data. A complete sampling strategy was utilised with parent coaches, in which all ABC-trained coaches were recruited (Palinkas et al., Citation2015). A purposeful sampling strategy was used for leaders, as the CWSs were organised differently. The leader who worked most closely with the family coach, and hence had most knowledge about ABC, was recruited. Finally, parents were recruited using a purposeful variation sampling, in which all initial parents who consented to be interviewed were recruited. After the first wave was interviewed, two criteria to provide the most amount of variation were applied. First, at least one family from each coach should be represented; second, parents should have various demographic characteristics (e.g. young/old, fathers/mothers). Attempts were made to recruit informants who dropped out of the feasibility study, but none were available.

Data collection

Demographics were collected at the time of recruitment. All interviews were carried out in the fall of 2018 and concluded in the fall of 2019, by the first author (HBB), a PhD candidate at RBUP at the time of the study. He had previous experience with various qualitative interview formats. The interviewer did not know the families or CWS leaders but had met most of the coaches prior to the interviews. Before each interview, informants were informed about the purpose of the interview and the professional background of the interviewer. A semi-structured interview guide was used to ensure that identical questions were asked in all interviews. Interviews were carried out via telephone because this was considered an efficient and low-cost approach of reaching participants. Moreover, it was considered preferable to face-to-face interviews with vulnerable families, as it allowed them to participate in locations they considered safe, without the physical presence of a stranger. This outweighed the potential drawbacks like the lack of body language.

Parents, coaches and leaders were interviewed using the open-ended strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) format (Helms & Nixon, Citation2010) to identify the various strengths, weaknesses, recommendations for improvements and challenges with the ABC-I intervention. During the first part of the interview, informants were invited to reflect on the open-ended SWOTs, such as ‘Please tell me about what you perceive as the [strengths/weaknesses/opportunities/threats] of the intervention’. At this point, the researcher interrupted the informants only occasionally to encourage further elaboration or elicit any additional SWOTs. These questions could be ‘Are there anymore [strengths/weaknesses/opportunities/threats]?’ and ‘Could you give me an example?’. This format adds a certain structure to the participants’ answers without imposing the researchers’ pre-conceptions about the topic (Lone et al., Citation2014). Subsequently, during the second part of the interview, the interviewer systematically worked through the main SWOTs identified by the informants to clarify and expand on his/her statements. The interviewer took notes throughout the interview. Interviews lasted between 49 and 135 minutes (M = 88.7) and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Identifying information was removed from the transcripts to ensure confidentiality.

Data analysis

The framework method (Gale et al., Citation2013) was used to identify themes regarding the informants’ experiences with ABC. The framework method is similar to thematic analysis and serves to identify commonalities and differences in qualitative data and draw conclusions clustered around themes. The defining feature of the method is the use of a matrix with cells for summarised data, which provides a structure for systematically reducing the data. The framework method was chosen due to its structure, enabling comparison both within and across cases. This would facilitate the highlighting of contrasting views within and between the different informants.

The analysis is carried out in seven stages: (1) transcription, (2) familiarisation with the data material, (3) coding of data, (4) development of an analytical framework, (5) application of the analytical framework, (6) charting data into the framework matrix, and (7) interpreting the data. Various approaches, like coder and data source triangulation, member checking and cyclical coding, was utilised to enhance the rigour of the analysis. In the present study, transcripts were initially reviewed by the first author (HBB) who made notes and coded data inductively in NVivo 12 software (QSR International, Citation2020). A second researcher (HJ) reviewed and coded a random selection of the same material. After coding independently, codes were compared and they agreed on a working analytical framework. A third researcher (FD) was regularly involved in reviewing the analytic process and structuring of the thematic framework. Transcripts were subsequently compared with the analytical framework and indexed in a coding tree. The coding tree was used as the basis for the framework matrix, in which data were abstracted on a group level and summarised. This matrix was used to interpret the data and identify interrelationships and differences between categories and informant groups. The analytic framework went through several iterations in which the research team (HB, HJ and FD) met regularly to revise it for best possible fit with the data. After agreeing on a final analytic framework, HB presented the findings to a group of coaches who provided feedback on its’ accuracy and made suggestions for revisions. This method of member-checking is a way of enhancing trustworthiness of the findings by exploring whether the analysis is congruent with the informants’ experiences (Carlson, Citation2010).

Results

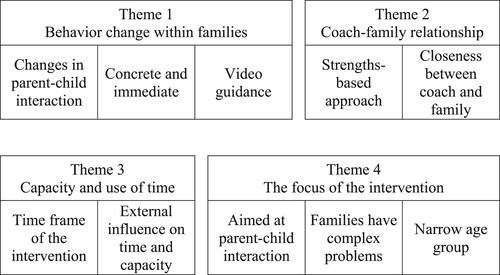

Four themes were derived from the data (): (1) Behaviour change within families; (2) Coach-family relationship; (3) Capacity and use of time; and (4) The focus of the intervention. The complete overview of the thematic framework is available as supplementary files (Appendix 1).

Theme 1: behaviour change within families

The first theme describes participants’ experiences of ways ABC brought about change among families and what aspects of the programme were associated with this change. This included the sub-themes ‘Changes in parent–child interaction’, ‘Concrete and immediate’ and ‘Video guidance’.

Changes in parent–child interaction

Participants described that ABC changed interactive behaviour between parents and children, with a particular emphasis on the change being very noticeable. This was partly due to the behavioural nature of the intervention, but also that changes occurred quickly. Many parent coaches described how parents adjusted their behaviour almost automatically after receiving a comment or watching a video:

It’s a very efficient method. You immediately see that they change behaviour when you say something. They do what you’ve talked about or commented on from one moment to the next (parent coach)

Concrete and immediate

The content and approach of ABC was described as concrete, direct and immediate. By ‘concrete’, participants were mainly referring to the in-vivo-comments by parent coaches and how these were directed at actual parent behaviour, rather than abstract concepts. One parent coach used the term ‘more surface than depth’ to describe that ABC was more behaviourally focused, compared to other interventions. Comments were also described as ‘here and now’ – they occurred simultaneously as parents were performing the behaviour, rather than being feedback on something that happened in a previous session.

You comment exactly when it happens. You don’t have to meet later and talk about what happened last time. You do that too, but it’s also in the moment, as it happens, here and now. (parent coach)

It's so simple and concrete. You don't have to think about it. You don't have to be very good at talking or anything like that. It's something anyone can do. (parent coach)

There are a lot of families in our municipality with language difficulties. And quite a few parents with poor cognitive functioning. So, to have this method where you work directly with the family and comment on what you see is incredibly important (leader)

Video guidance

The use of video is essential to ABC. All sessions are videotaped for the purpose of video-feedback to parents and supervision of coaches. Additionally, short videos of other families are used to illustrate key concepts like ‘following the lead’. Participants perceived the use of video as important in helping parents understand these concepts and especially how they related to the parents’ own behaviour. Parents talked about the difficulty of seeing oneself ‘from the outside’ and how watching videos helped them become conscious of their own behaviour:

When you're with your child, you don't notice that you're smiling. But in the movie, I saw that I smiled to my son and I saw his reaction. That made me really happy. (mother)

I spend more time on the videos than I’m supposed to. When you have such wonderful material, it would be nice to use it more. There’s potential to see more things or to stop and discuss it a little more (parent coach)

You encounter scepticism from most parents when it comes to filming. I feel like I've become pretty good at convincing them by now, but I have encountered parents who refused due to filming. It just wasn’t an option for them. (parent coach)

Theme 2: coach-family relationship

The second theme covers experiences about the relationship between the family and parent coach and ways in which ABC affected this relationship. This included the sub-themes ‘Strengths-based approach’ and ‘Closeness between coach and family’.

Strengths-based approach

Throughout home visits, coaches commented on parents’ strengths, with particular emphasis on what they achieved in terms of target behaviours. This was an aspect of ABC that parents appreciated, saying that these comments made them feel better about themselves:

I guess the point of the course was for you to regain some faith in yourself. [My coach] was good at pointing out things I did well. Not going on about the things you do wrong, but rather focus on the things you do right (mother)

You reinforce the stuff that works. That’s especially important in the CWS context because we tend to focus on the stuff that doesn’t work. I think that has an impact on the coach-parent relationship. Maybe parents will stop thinking about the CWS as the big bad wolf (leader)

One family considered themselves done after three sessions. They told the caseworker that “the parent coach says that I’m so good, so I don’t want further guidance. I don’t need it.” The family then withdrew their consent for further guidance (parent coach)

Closeness between coach and family

The emphasis on parents’ strengths helped enhance the social and emotional bond between coach and family. This may be one of the reasons parents described themselves as close with their parent coach, saying that they felt safe and that they could talk to them about anything. They also used terms like ‘get along well’, ‘good chemistry’ and having ‘a great tone together’. Many pointed out the importance of communication, saying that the coach was good at explaining things they had difficulty grasping and that s/he used words that were easy to understand.

I thought it was so nice that [our coach] was there. We could talk to her about anything and she listened and tried to help us. (father)

You get very close to the way they live. Just by sitting on the floor. It’s completely different from what most family counsellors do. Being in it together. (parent coach)

I’ve received guidance on how to respond [to the child] and how to include mom or dad. Instead of going in and picking up or playing with the child. That made me more conscious of my role in the whole thing. (parent coach)

Theme 3: capacity and use of time

The third theme covers ways in which families’ and coaches’ capacity and use of time played a role in the implementation of the programme. This included two sub-themes: ‘Timeframe of the intervention’ regarding issues inherent to the ABC sessions; and ‘External influence on time and capacity’ about how outside forces influenced the implementation of ABC.

Timeframe of the intervention

ABC consists of 10 home visits, each lasting approximately 60 minutes. The general opinion across informants was that this was too brief. Coaches and leaders were concerned that there was not enough time to ensure lasting change and that some families may struggle to grasp the programme’s content.

Many families need us to repeat the same subjects over several sessions. Even after 10 sessions we’re not entirely finished. So, there may be a need for some follow-up. (leader)

Ten hours over 10 sessions go extremely fast. All points were brought up, but it missed the intensification of the main points. (mother)

Despite participants describing the programme as too brief, a few coaches and leaders viewed it as just the right amount of time. Coaches generally had a very busy schedule, so they appreciated being able to provide ‘a great amount of help in a short amount of time’.

External influence on time and capacity

A recurring topic among most was that various factors in everyday life influenced their involvement with ABC. Parent coaches described their schedule as very busy and unpredictable, with crises occurring regularly that require immediate action.

Our workday is really unpredictable. When there’s an emergency you feel like you must drop everything you’ve got in your hands. Or at least you think “I should have been there.” That's just part of our daily routine. (parent coach)

Fidelity-supervision and video coding was quite demanding. There’s not much time set aside for it. So, much work must be done during evenings and weekends. But I think the content of the fidelity-supervision was very good. It’s absolutely necessary to become a good ABC-coach. (parent coach)

It’s been quite time-consuming, in the sense that coaches have also undergone training. But I don’t know whether the method itself, when you know it and apply it, takes any more time than any of the other things we do (leader).

I have a lot to do as a single mom. There are meetings with the CWS and community health centre. I take my child out to play. I take driving lessons. And I have a paternity case going with my child’s dad. When we were doing [ABC], I was doing all these things at the same time. But even though I was tired and needed a break, I never turned down a session. (mother)

Theme 4. The focus of the intervention

The fourth theme covers experiences regarding who and what ABC targeted, including eligibility and programme content. This included the sub-themes ‘Families have complex problems’, ‘Aimed at parent–child interaction’ and ‘Narrow age group’.

Families have complex problems

One major concern among coaches and leaders was that families have complex problems and most need help with more than just interactional problems. For instance, coaches felt that it was demanding not to address topics outside the ABC manual during home visits, especially when parents had questions they regarded as important:

Questions about meals, sleep and things like that are not part of ABC. Sometimes I felt like I rejected them, because I want to be attentive to their concerns (parent coach)

Many families have a lot of complex issues. So, I think ABC needs to be a part of a larger package. I’m not saying that there’s anything missing in the program, but I think that, on its own, it’s not enough for most of our families (leader)

Aimed at the parent–child interaction

The primary focus of ABC is the parent–child interaction. Despite the issues described in sub-theme 4.1, parent coaches generally viewed parent–child interaction as essential to families’ well-being. Moreover, the defined scope and strict rules for adherence to the manual helped coaches focus on the programme:

It feels good to narrow the work down to one thing. Not having to be the caretaker of everything (parent coach)

Narrow age group

Coaches viewed ABC as a great addition to the CWS, because most CWS services did not have an intervention for infants. Yet, most services struggled to recruit enough participants, which coaches mainly attributed to the age limit. They received few referrals from services for infants (e.g. community health centres), compared to services for older children. Therefore, many expressed a desire to expand the age limit:

If we could have [ABC] up to 4 years we would get many more families, because kindergartens would refer children. They’re better at referring than community health centres, because they see the children much more (parent coach)

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore the experiences of parents, parent coaches and their leaders in implementing ABC in Norwegian CWS services and make recommendations for adapting the programme for future use. Overall, ABC seemed useful and acceptable to most participants. One of the major findings was that coaches and parents perceived a noticeable change in parent–child interactive behaviour, especially in terms of the target behaviours for ABC. This is in line with previous studies on ABC, showing an increase in sensitivity and reduction in intrusiveness (Bernard et al., Citation2015; Garnett et al., Citation2020; Perrone et al., Citation2021). Qualitative studies carried out in the U.S. also show that parents and home-visitors experience behavioural change and that learning behaviours like following the child’s lead is perceived as a benefit of ABC (Aparicio et al., Citation2016; West et al., Citation2017).

One of the aspects of ABC which participants viewed as facilitating change was commenting on concrete parent behaviours. Rather than explaining what caregivers should do and expect them to perform said behaviours, coaches reinforced behaviours by commenting on them in vivo. This distinction between directive and responsive coaching techniques has been tested before, showing that commenting in reaction to behaviour (i.e. responsive) is more strongly associated with behaviour change than coaching prior to a behaviour (i.e. directive; Barnett et al., Citation2017; Heymann et al., Citation2021). Participants in the current study highlighted how ABC’s emphasis on behaviour, rather than reflection, was suitable for parents with intellectual difficulties. This is important, considering that parents with intellectual disabilities are disproportionally represented in CWSs (Slayter & Jensen, Citation2019). There is also previous research suggesting that skill-focused interventions that apply behaviour teaching strategies like feedback, praise and tangible reinforcement are especially effective for parents with intellectual disabilities (Coren et al., Citation2018).

The use of video feedback was often mentioned as a practice element that helped bring about change. Watching videos helped parents get new perspectives on their caregiving and better understand how target behaviours should be performed. However, some coaches noted that families often were sceptical towards being filmed. This is in line with ABC and other interventions where parents describe video feedback as helpful, but the experience of being recorded as uncomfortable (Aparicio et al., Citation2016; O’Toole et al., Citation2021). Scepticism toward video feedback may stem from a general lack of trust in CWSs. Coaches and leaders mentioned lack of trust in the CWS as a challenge in general, and some parents described being apprehensive before starting ABC due to negative experiences with CWS. However, ABC’s strengths-based approach seemed to counteract some of these negative sentiments. Interviews with mothers who participated in ABC in the U.S. revealed similar experiences, with mothers being sceptical at first, but eventually becoming more trusting (Aparicio et al., Citation2016).

Participants had different perspectives on the duration of ABC, with most considering it too brief. Most suggested adding follow-up sessions to spend more time on topics parents found difficult. As some parents may have intellectual or language difficulties, extending duration or dosage for these participants may be beneficial. Although the idea of adapting a manualised intervention is somewhat controversial (Castro & Yasui, Citation2017), one may argue that, if core elements are adhered to, adapting an intervention to fit client or contextual factors could be necessary to enhance its’ acceptability (von Thiele Schwarz et al., Citation2019).

A central issue covered by most parent coaches and leaders was that ABC mainly focuses on parent–child interaction. Many coaches viewed the emphasis on the parent–child relationship as fundamental to the child and family’s well-being. This is supported by studies which demonstrate positive cascading consequences for children who receive ABC (e.g. Bernard et al., Citation2017; Zajac et al., Citation2019). On the other hand, coaches and leaders were concerned that families would not get the help they needed in other areas. Suggested solutions included having a second caseworker assist the family with issues unrelated to ABC or refer families to other services. However, many CWSs have limited resources, high caseloads and staff turnover (Edwards & Wildeman, Citation2018; Olsvik & Saus, Citation2020). Therefore, solutions that require additional personnel may not be viable for all CWSs.

To most leaders and coaches, ABC was highly needed because their service did not have any interventions targeted at infants. However, they also noted recruitment difficulties because few infants are generally being referred to CWSs. An expansion of the age limit would likely result in more eligible families, although this would either entail making changes to the manual or train coaches in ABC-T. The risk of choosing the former option would be that, even though most of the core elements would still be relevant for this age group, it would fail to address important developmental challenges that occur during toddlerhood, like balancing increased autonomy and emotion-regulation (Sroufe, Citation2013). Nevertheless, training coaches in another intervention would require resources beyond the costs of ABC itself. Considering how the cost of a programme is an important barrier to sustainment (Roundfield & Lang, Citation2017), adding an additional programme may be a risk in and of itself.

Limitations and recommendations

A limitation of this study is that all parent coaches were in the process of being certified when families were included. Therefore, all views regarding the implementation of ABC reflect an intervention being delivered by practitioners in training and not of experienced parent coaches. When implementing ABC in the future, services must be especially attentive to matters related to recruitment, caregiver distrust and the various problems that each family may face. The following recommendations reflect these issues:

The availability of eligible families should be considered by each individual service before implementing ABC, as there is a risk of not recruiting enough families. This is particularly true for Norwegian CWSs, but may be equally relevant for CWSs in other countries where young children are underrepresented.

Vulnerable families may initially be distrustful towards parent coaches, especially regarding video recording. Hence, they should be thoroughly informed about filming prior to receiving ABC. Careful preparation of families may also improve their willingness to participate.

Services that provide multiple forms of support, such as the Norwegian CWS, must find ways to help families with problems not covered by ABC. For instance, having one professional to provide ABC and a second to deal with other issues.

Conclusion

ABC was generally well-received by families, parent coaches and CWS leaders. The programme’s core elements like in-vivo-commenting and video feedback were considered important for bringing about change. The strengths-based approach helped reduce families’ resistance towards parent coaches and strengthen the therapeutic relationship. Participants had conflicting viewpoints on the duration of the intervention, although there seemed to be a shared desire for making adaptations to suit the needs of the individual family. Leaders and parents were concerned that the narrow focus of the intervention content and age group could result in families not receiving the help they need but were happy they could offer an efficacious intervention for the youngest children in the CWS.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (31.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hans Bugge Bergsund

Hans Bugge Bergsund has a master’s degree in Psychology and is currently working as a PhD student on a feasibility study of Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up (ABC) in Norway. His main research interests are attachment, parent–child interaction and implementation of evidence-based programmes for infants and toddlers.

Filip Drozd

Filip Drozd has a PhD in psychology and is working on the development and evaluation of interventions to support and improve the quality of child and family services (0–5 years). His main current research interests are evaluation and implementation of evidence-based programmes, infant and parent sleep, and perinatal mental health.

Heidi Jacobsen

Heidi Jacobsen is a clinical psychologist and has a PhD in psychology. She is a researcher at the Centre for Child and Adolescent Mental Health in Oslo, Norway. Her main research interests are foster care, attachment, and child development. She is the principal investigator for the project: Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-Up Intervention: A pilot study of home-based intervention with families with young children in the CWS.

References

- Abbott, J. (2014). The distinction between randomized clinical trials and preliminary feasibility and pilot studies: What they are and are not. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 44(8), 555–558. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2014.0110

- Altafim, E., & Linhares, M. (2016). Universal violence and child maltreatment prevention programs for parents: A systematic review. Psychosocial Intervention, 25(1), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psi.2015.10.003

- Aparicio, E., Denmark, N., Berlin, L., & Harden, B. (2016). First-generation Latina mothers’ experiences of supplementing home-based early head start with the attachment and biobehavioral catch-up program. Infant Mental Health Journal, 37(5), 537–548. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21586

- Barnett, M.L., Niec, L.N., Peer, S.O., Jent, J.F., Weinstein, A., Gisbert, P., Simpson, G (2017). Successful therapist–parent coaching: How in vivo feedback relates to parent engagement in parent–child interaction therapy. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 46(6), 895–902. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2015.1063428

- Bernard, K., Dozier, M., Bick, J., Lewis-Morrarty, E., Lindhiem, O., Carlson, E. (2012). Enhancing attachment organization among maltreated children: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Child Development, 83(2), 623–636. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01712.x

- Bernard, K., Lee, A., & Dozier, M. (2017). Effects of the ABC intervention on foster children’s receptive vocabulary: Follow-up results from a randomized clinical trial. Child Maltreatment, 22(2), 174–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559517691126

- Bernard, K., Simons, R., & Dozier, M. (2015). Effects of an attachment-based intervention on child protective services–referred mothers’ event-related potentials to children’s emotions. Child Development, 86(6), 1673–1684. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12418

- Carlson, J. (2010). Avoiding traps in member checking. Qualitative Report, 15(5), 1102–1113. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2010.1332

- Castro, F., & Yasui, M. (2017). Advances in EBI development for diverse populations: Towards a science of intervention adaptation. Prevention Science, 18(6), 623–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-017-0809-x

- The Child Welfare Act. (1992). https://lovdata.no/lov/1992-07-17-100.

- Christiansen, Ø, Bakketeig, E., Skilbred, D., Madsen, C., Havnen, K.J.S., Aarland, K., Backe-Hansen, E. (2015). Forskningskunnskap om barnevernets hjelpetiltak https://bufdir.no/bibliotek/Dokumentside/?docId=BUF00003223

- Chu, A., & Lieberman, A. (2010). Clinical implications of traumatic stress from birth to age five. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6(1), 469–494. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131204

- Cicchetti, D., Rogosch, F., & Toth, S. (2006). Fostering secure attachment in infants in maltreating families through preventive interventions. Development and Psychopathology, 18(3), 623–649. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579406060329

- Coren, E., Ramsbotham, K., & Gschwandtner, M. (2018). Parent training interventions for parents with intellectual disability. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2018(7), 7. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007987.pub3

- Creswell, J., & Miller, D. (2000). Validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory into Practice, 39(3), 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip3903

- Dobson, D., & Cook, T. (1980). Avoiding type III error in program evaluation. Results from a field experiment. Evaluation and Program Planning, 3(4), 269–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-7189(80)90042-7

- Dozier, M., & Bernard, K. (2019). Coaching parents of vulnerable infants: The attachment and biobehavioral catch-up approach. Guilford Publications.

- Edwards, F., & Wildeman, C. (2018). Characteristics of the front-line child welfare workforce. Children and Youth Services Review, 89, 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.04.013

- Egeland, K. M., Hauge, M. I., Ruud, T., Ogden, T., Heiervang, K.S. (2019). Significance of leaders for sustained use of evidence-based practices: A qualitative focus-group study with mental health practitioners. Community Mental Health Journal, 55(8), https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-019-00430-8

- Embry, D., & Biglan, A. (2008). Evidence-based kernels: Fundamental units of behavioral influence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 11(3), 75–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-008-0036-x

- Eng, H., Reedtz, C., & Martinussen, M. (2018). Effekter av psykososiale intervensjoner for sped- og småbarn 2018 [The effects of psychosocial interventions for infants and toddlers 2018]. Tromsø.

- Ferlie, E., & Shortell, S. (2001). Improving the quality of health care in the United Kingdom and the United States: A framework for change. The Milbank Quarterly, 79(2), 281–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.00206

- Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., & Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

- Garnett, M., Bernard, K., Hoye, J., Zajac, L., & Dozier, M. (2020). Parental sensitivity mediates the sustained effect of attachment and biobehavioral catch-up on cortisol in middle childhood: A randomized clinical trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 121, 104809, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.104809

- Gubbels, J., van der Put, C., & Assink, M. (2019). The effectiveness of parent training programs for child maltreatment and their components: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(13), 2404. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132404

- Helms, M., & Nixon, J. (2010). Exploring SWOT analysis – Where are we now? A review of academic research from the last decade. Journal of Strategy and Management, 3(3), 215–251. https://doi.org/10.1108/17554251011064837

- Heymann, P., Heflin, B. H., & Bagner, D. M. (2021). Effect of therapist coaching statements on parenting skills in a brief parenting intervention for infants. Behavior Modification, https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445520988140

- Lind, T., Raby, K. L., Caron, E. B., Roben, C. K. P., & Dozier, M. (2017). Enhancing executive functioning among toddlers in foster care with an attachment-based intervention. Development and Psychopathology, 29(2), 575–586. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579417000190

- Lone, J. A., Bjørklund, R. A., Østerud, K. B., Anderssen, L. A., Hoff, T., & Bjørkli, C. A. (2014). Assessing knowledge-intensive work environment: General versus situation-specific instruments. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(3), 469–482. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2012.750449

- Olsvik, B., & Saus, M. (2020). Coping with paradoxes: Norwegian child welfare leaders managing complexity. Child Care in Practice, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2020.1776683

- O’Toole, C., Lyons, R., & Houghton, C. (2021). A qualitative evidence synthesis of parental experiences and perceptions of parent–child interaction therapy for preschool children with communication difficulties. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 64(8), 3159–3185. https://doi.org/10.52015/numljci.v19i1.102

- Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(5), 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

- Perrone, L., Imrisek, S., Dash, A., Rodriguez, M., Monticciolo, E., & Bernard, K. (2021). Changing parental depression and sensitivity: Randomized clinical trial of ABC’s effectiveness in the community. Development and Psychopathology, 33(3), 1026–1040. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579420000310

- QSR International. (2020). NVivo Version 12. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home.

- Roundfield, K., & Lang, J. (2017). Costs to community mental health agencies to sustain an evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Services, 68(9), 876–882. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201600193

- Slayter, E., & Jensen, J. (2019). Parents with intellectual disabilities in the child protection system. Children and Youth Services Review, 98, 297–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.01.013

- Sroufe, L. (2013). The promise of developmental psychopathology: Past and present. Development and Psychopathology, 25(4 PART 2), 1215–1224. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000576

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. (2017). Child maltreatment 2015. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/resource/child-maltreatment-2015.

- von Thiele Schwarz, U., Aarons, G., & & Hasson, H. (2019). The value equation: Three complementary propositions for reconciling fidelity and adaptation in evidence-based practice implementation. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4668-y

- West, A., Aparicio, E., Berlin, L., & Harden, B. (2017). Implementing an attachment-based parenting intervention within home-based early head start: Home-visitors’ perceptions and experiences. Infant Mental Health Journal, 38(4), https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21654

- Zajac, L., Raby, K., & Dozier, M. (2019). Sustained effects on attachment quality in middle childhood: The attachment and biobehavioral catch-up intervention. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61(4), 417–474. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13146