ABSTRACT

With a high prevalence of mental health disorders in Europe and the increasing call for human-rights approaches in their treatment, the number of community-based mental health (CBMH) interventions is growing within the region. However, the implementation of these CMBH interventions differs between countries and regions, especially between Western and Eastern European countries. The reasons for these differences are based on societal and health systems, but also the design and implementation of the intervention. This systematic literature review examined the existing literature on CMBH interventions in Europe, to identify facilitators and barriers in the implementation process. Emerging themes that were found are the importance of collaboration, the availability of adequate resources, and the consideration of the community perspective in the process. The differences between Western and Eastern Europe which were discovered were mostly caused by a lack of financial and human resources and a higher existing stigma around mental health disorders in communities.

ZUSAMMENFASSUNG

Angesichts der hohen Prävalenz psychischer Störungen in Europa und der zunehmenden Forderung nach menschenrechtlich-basierten Ansätzen bei der Behandlung dieser Störungen nimmt die Zahl der gemeindeorientierten, psychiatrischer (community-based mental health, CBMH) Maßnahmen in dieser Region zu. Die Umsetzung dieser gemeindeorientierten Maßnahmen ist jedoch von Land zu Land und von Region zu Region unterschiedlich, insbesondere zwischen west- und osteuropäischen Ländern. Die Gründe für diese Unterschiede liegen in den Gesellschafts- und Gesundheitssystemen, aber auch in der Gestaltung und Umsetzung der Maßnahmen. Im Rahmen dieser systematischen Literaturübersicht wurde die vorhandene Literatur zu CMBH-Maßnahmen in Europa untersucht, um Erleichterungen und Hindernisse im Umsetzungsprozess zu ermitteln. Dabei kristallisierten sich folgende Themen heraus: die Bedeutsamkeit der Zusammenarbeit, die Verfügbarkeit angemessener Ressourcen und die Berücksichtigung der Gemeinschaftsperspektive in diesem Prozess. Die festgestellten Unterschiede zwischen West- und Osteuropa sind vor allem auf einen Mangel an finanziellen und personellen Ressourcen sowie auf eine stärkere Stigmatisierung von psychischen Störungen in den Gemeinden zurückzuführen.

Introduction

According to the Global Burden of Disease and Injury (GBD) study from 2016, more than one billion people worldwide have a mental health disorder that negatively impacts their ability to function productively within their community (Rehm & Shield, Citation2019). The impacts of mental health-related symptoms are wide-reaching, affecting the work, home and social lives of those who suffer from them (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2019). The growing burden of mental health challenges across the lifespan has resulted in increased attention being paid to solutions, treatment, and interventions (WHO, Citation2019). However, despite efforts to improve mental health, effective treatment coverage remains low (Pathare et al., Citation2018). Even in regions that are traditionally viewed as having sufficient resources to provide mental health support, such as Europe, mental health disorders continue to dominate as a significant cause of disability and disease (WHO, Citation2015). Therefore, more effective, sustainable and contextually-relevant interventions and services are needed (WHO, Citation2019).

The WHO European Region, which will serve as the definition of Europe in this paper, consists of 53 member states with over 900 million inhabitants (WHO, Citation2015). Within the region differences are numerous, meaning that these populations face differences in social, cultural, political, and economic contexts, which in turn results in different experiences, and prevalence of and approaches to mental health disorders (WHO, Citation2015). For instance, mental health disorders are the greatest contributor to the burden of disease in Western European countries (WECs)Footnote1, whilst in Eastern European countries (EECs)Footnote2 mental health disorders are secondary to other non-communicable diseases such as cardio-vascular diseases (WHO, Citation2015). However, as the number of disability-adjusted life years per 100.000 people in EECs is similar to the one in WECs (Rehm & Shield, Citation2019).

It has also been widely acknowledged that interregional differences exist in the approach to mental healthcare (Knapp et al., Citation2005; Muijen & McCulloch, Citation2019; Petrea, Citation2012; Thornicroft & Rose, Citation2005). For example, in WECs the process of deinstitutionalisation, the replacement of long-stay psychiatric hospitals with more amenable community mental health services, is nearly complete and human rights violations in healthcare take place less often and models that focus on community-based interventions are preferred (Knapp et al., Citation2005; Thornicroft & Rose, Citation2005). On the other hand, many EECs have a complex, recent socio historical context that include political transfrom-ation and sovereignty from the Soviet Union. Despite these changes, the impact of the Soviet Union in the region has remained in the treatment of mental health, which focuses on more traditional, psychiatric approaches (Muijen & McCulloch, Citation2019). This can be seen for example in the lack of clinical psychologists or social health workers in mental health, and a higher stigma (Muijen & McCulloch, Citation2019). Another difference between both parts of Europe is the lower spending on mental healthcare in Eastern Europe as well as the existence of more remote locations with lower healthcare coverage (Dlouhy & Barták, Citation2013; Krupchanka & Winkler, Citation2016; Muijen & McCulloch, Citation2019). Because of these differences in context, a proven way to provide contextually-relevant interventions is through community-based interventions (WHO, Citation2021).

In recent years, the development of holistic, community-based interventions has taken precedence over traditional, psychiatric approaches. Community-based mental health (CBMH) interventions consist of services that are provided in the community and focus on continuous and multi-factored help (American Psychological Association, Citation2021). Often the focus is on preventive services, meaning mental health is treated by indirect methods like consultation or education rather than primarily prescribing medicine (American Psychological Association, Citation2021). This form of treatment is seen as a person-centred and rights-based approach to improving mental health where all social determinants of mental health are taken into account to respond to the immediate and long-term needs of individuals (WHO, Citation2021). Additionally, it is based on a recovery approach that prioritises integrating people back into their community, fostering them purpose, meaning and independence (WHO, Citation2021). Beneficial aspects of CMBH in contrast to the clinical psychiatric treatment are the allowance for people to exercise their legal capacity, promoting the autonomy of patients, and using non-coercive practices (WHO, Citation2021). Due to this notion, the WHO Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2020–2030 was published as guidance for countries and other stakeholders to reform mental health programmes (WHO, Citation2021). The outcomes of the global trend supporting community-based treatment can also be seen in Europe, with a variety of CBMH interventions, projects, and research taking place in recent years (Joint Action for Mental Health and Well-being, Citation2021).

Due to the increased attention on CBMH interventions as suitable and preferable methods of mental healthcare in Europe, it is unsurprising that there is available literature on this topic. For example, there is literature that focuses on general mental health services in certain countries or regions, as well as comparisons between different mental healthcare systems within Europe (Muijen & McCulloch, Citation2019; Placella, Citation2019; Sadeniemi et al., Citation2018; Taube & Quentin, Citation2020). Additionally, research studies with a broader view region-wise focus either on certain perspectives of for example health professionals, or certain kinds of CBMH interventions (Patalay et al., Citation2017; Roth et al., Citation2021; Triliva et al., Citation2020). However, a comparison between the more-deinstitutionalised Western European health services and the more-institutionalised Eastern European health services is lacking. Furthermore, the philosophical idea, here defined as the motive and the anticipated outcome when using CBMH interventions, in different regions is not documented sufficiently. Therefore, this literature review will answer the following research question: What are success factors for the implementation of CBMH interventions in Europe?

Methods

Study design

A systematic review was conducted to find suitable information regarding the success factors of CBMH programmes and interventions in Europe. This review type was chosen because it combines the strengths of critical reviews, like a critical quality evaluation of findings and detailed synthesis of significant items, with a comprehensive search process to achieve best evidence synthesis (Grant & Booth, Citation2009). In this way, the best recommendations can be made based on best practices (Triliva et al., Citation2020). The review places emphasis on qualitative methods to extract factors contributing to a successful implementation of interventions from the literature. Implementations in this review are seen as successful if the different parts of the implementation of an intervention are facilitated and therefore can lead to the intervention being integrated into practice. Additionally, the main focus was on health systems approaches on national, as well as regional levels. This decision was made to ensure more widely applicable outcomes, as results from locally successful interventions might not be up scalable.

Search strategy

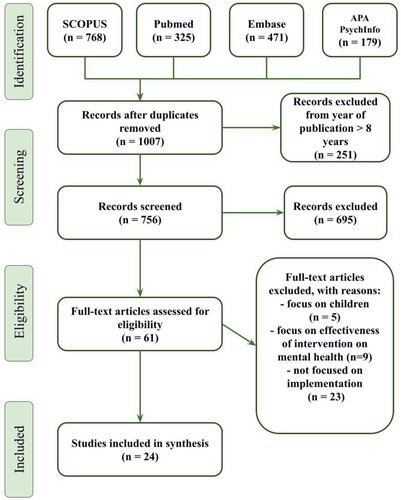

In order to find relevant articles of good quality, literature searches were conducted in four academic databases: SCOPUS, PubMed, Embase, and APA PsycInfo. The literature search was done on the 30th of November 2021 using Boolean search strings that included four key concepts: community-based, mental health, intervention, and Europe/European countries. The full search strategy can be found in Appendix A. Both scientific and grey literature publications were considered for the literature review. The inclusion of grey literature into this review was needed as projects at national and regional levels are often described more elaborately in policy papers by national and local governments. In addition, grey literature has a stronger focus on philosophical strategies behind policies, systems, and programmes and therefore provides a deeper understanding.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

During the searching and screening phases of this review, certain inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied. For studies to be included, they needed to have a mental-health focus and be implemented within the WHO European Region. Additionally, papers were included if a community-based approach was used and they were published or implemented in the last eight years. This was done to make sure primarily recent information about the topic was assessed. Only peer-reviewed articles were included to increase quality and credibility. The type of CBMH intervention and mental health focus were not limited. Articles were excluded when they described clinical trials on mental health, described study protocols, were not written in English, focused on children/adolescents, or were not free to access the full text.

Identification of relevant Studies

Once the initial search was complete, articles were screened by two independent researchers in Rayyan. The PRISMA protocol was used to ensure rigour during the screening process. Both independent researchers blind screened the articles and made decisions on the inclusion or exclusion of publications. First, articles were screened for the relevance of the title and abstract. Articles approved by both researchers were automatically included in the full-text screening, while more ambiguous articles were first discussed among the researchers to decide on them. After this, the full text of included studies was assessed on eligibility. Some full-text articles were excluded in the second screening due to a sole focus on children as patients, exclusively assessing the effectiveness of the intervention, or the lack of discussing the implementation of an intervention. Studies that were included after this second screening were used for the data extraction.

Included studies

For this literature review, 1007 publications, excluding duplicates, from the searching stage were identified. From these publications, 756 titles and abstracts were screened and publications older than eight years were excluded. After exclusion, 61 articles were assessed for eligibility. The exclusion process concluded in 24 full-text articles that were used for the synthesis. shows the PRISMA diagram flow of the search strategy leading to the final included studies in the literature review.

Data extraction and analysis

Data from the final included articles were extracted into a data extraction sheet on Microsoft Excel for ease of analysis. Extraction focused on factors such as country/countries of interest, level of implementation (national/regional or local), population of interest, types of conclusions of the study, type of intervention, philosophical ideas around the intervention, outcome of the intervention and facilitators and barriers. Studies were divided and extracted by two reviewers and afterwards compared to see similarities between them and to develop general motives for facilitators and barriers, being the result of the literature review. The extracted data were deductively analysed in order to explore themes relating to the facilitators and barriers that impacted the successful implementation of CBMH interventions. This was also done for the philosophical ideas around the interventions. Inductive analysis approaches were also used in order to allow for new, pertinent themes to emerge from the deduced barriers and facilitators.

Quality assessment

The data of the included studies were critically appraised by two independent reviewers, taking the strengths and limitations of each study into consideration. For qualitative studies, the quality appraisal was done with the CASP checklist (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, Citation2018). For mixed methods data collection, the quality appraisal was done with the MMAT checklist (Pluye & Hong, Citation2014). Lastly, the quality of grey literature was assessed with the AACODS checklist (Tyndall, Citation2010). Studies were included in the synthesis when checked mostly ‘yes’ and no significant concerns regarding quality standards were detected in the respective checklist.

Results

This review aimed to determine factors that promoted the successful implementation of CBMH interventions. The analysis led to three overarching themes emerging regarding the facilitators and barriers to implementation which are: collaboration as a tool for success, the importance of sufficient resources, and community perspective on mental health.

Study characteristics

Of the 24 studies included, eight articles were concerning EECs, fourteen concerning WECs and two articles included both EECs and WECs. Most of the studies used a qualitative approach for data collection (n = 14), but grey literature (n = 7), mixed methods studies (n = 2), and one systematic review were included as well. Nearly all studies included information about mental healthcare in a European country on a national or regional level, only two studies focused on a local intervention. The majority of the studies included stakeholders such as health professionals, healthcare workers, and managers as participants in their research. Additionally, different types of mental health disorders were mentioned in the studies. A summary of the included papers is shown in .

Table 1. Study characteristics of included papers.

Theme 1: collaboration as a tool for success

Among the included literature, several concepts emerged regardless of geographical localisation. One of the main themes that arose was ‘collaboration as a tool for success’ (n = 16). An important aspect mentioned in several papers was the establishment of cross-sectional relationships (n = 14). The provision of CBMH treatment was seen not solely as the responsibility of healthcare professionals, but also as an approach that needs the support of social workers, education professionals, or local volunteers in non-profit organisations (Baxter & Fancourt, Citation2020; Hegerl et al., Citation2019; Markström & Lindqvist, Citation2015; Montgomery et al., Citation2019; Petrea et al., Citation2020; Placella, Citation2019; Quirke et al., Citation2020; Wong et al., Citation2021). There was a high need for strong collaborations between different sectors to be able to implement effective CBMH intervention (Baxter & Fancourt, Citation2020; Borgi et al., Citation2019; Fieldhouse et al., Citation2017; Markström, Citation2014; Nicholson et al., Citation2021; Triliva et al., Citation2020; Van Hoof et al., Citation2015). Collaborations between these individuals or agencies enabled multi-level approaches to integrate mental health treatments in the community, e.g. the development of awareness campaigns or educational programmes about mental health to address existing stigma and lack of knowledge (Hegerl et al., Citation2019; Markström & Lindqvist, Citation2015; Petrea et al., Citation2020; Wong et al., Citation2021).

Another mentioned aspect was the necessity of commitment from the involved stakeholders (n = 10). These could be politicians, hospital administrators, healthcare professionals, but also patients and communities (Fieldhouse et al., Citation2017; Hegerl et al., Citation2019; Markström & Lindqvist, Citation2015; Montgomery et al., Citation2019; Morzycka-Markowska et al., Citation2015; Petrea et al., Citation2020; Quirke et al., Citation2020; Taube & Quentin, Citation2020; Van Hoof et al., Citation2015). It was shown that interventions were seen to be more successful and comprehensive if the government took ownership of the transformation and prioritised it in their mental healthcare government as it happened in Sweden and Moldova (Markström & Lindqvist, Citation2015; Petrea et al., Citation2020). Apart from including high-level stakeholders, it seemed to be important to include the professionals which directly work with patients in the process for a higher level of commitment from them (Taube & Quentin, Citation2020). In EECs, it seemed more necessary to have support from politicians and other high-level stakeholders, caused by an intrinsic motivation or e.g. external pressure from international organisations (Morzycka-Markowska et al., Citation2015; Petrea et al., Citation2020; Quirke et al., Citation2020; Taube & Quentin, Citation2020; Wong et al., Citation2021).

Furthermore, a patient-centred design of the intervention emerged as another success factor (n = 8). This design was enabled by involving service-users and their voices at all levels of planning and implementation, establishing client-tailored objectives in the provision, offering a variety of services to respond to the individual needs, or adapting the programme locally to the emerging needs of patients (Baxter & Fancourt, Citation2020; Montgomery et al., Citation2019; Nicholson et al., Citation2021; Triliva et al., Citation2020). Looking at WECs, an emphasis on person-centred care seemed to be a facilitator for successful implementation of CBMH interventions (Baxter & Fancourt, Citation2020; Hegerl et al., Citation2019; Lohmeyer et al., Citation2019; Markström, Citation2014; Nicholson et al., Citation2021; Sandhu et al., Citation2017; Triliva et al., Citation2020).

An important philosophical idea mentioned in most articles is the idea that CBMH services should focus on helping people to reintegrate into society. The goal of the intervention is not solely to treat the disorder of the patient, but also to look beyond this aspect and support other needs of this person (Baxter & Fancourt, Citation2020; Borgi et al., Citation2019; Hegerl et al., Citation2019; Markström & Lindqvist, Citation2015; Petrea et al., Citation2020; Taube & Quentin, Citation2020). Another philosophical idea that came forward was to tailor the service provision according to the needs of the patients (Hegerl et al., Citation2019; Szabzon et al., Citation2019; Taube & Quentin, Citation2020).

A barrier, however, that was mentioned in many papers was the fragmentation of services in the system (Bażydło & Karakiewicz, Citation2016; Giannakopoulos & Anagnostopoulos, Citation2016; Markström, Citation2014; Montgomery et al., Citation2019; Muijen & McCulloch, Citation2019; Quirke et al., Citation2020; Van Hoof et al., Citation2015;). The division of responsibilities as part of deinstitutionalisation led to a lack of communication between the different levels and stakeholders within the system (Muijen & McCulloch, Citation2019; Van Hoof et al., Citation2015). This lack of communication resulted in misunderstandings hindering the successful implementation of CBMH services (Markström, Citation2014).

Theme 2: importance of adequate resources

A second theme that emerged was the importance of adequate resources for implementation – specifically in terms of funding. If financial support was given, especially for the long term, this provided security and led to a sustainable implementation of community-based care. Therefore, the source of funding had a profound influence on the success, resulting in differences in quality between wealthy and poor municipalities, lack of key therapies, or no continuity of certain activities (Baxter & Fancourt, Citation2020; Nicholson et al., Citation2021; Szabzon et al., Citation2019). Lack of funding and financial support by the government was said to be one of the main factors in why inpatient mental health services could not be transferred successfully to community-based interventions. In countries like Germany and the Netherlands, CBMH interventions came with high costs (Lohmeyer et al., Citation2019). However, in Latvia, the transfer from hospital services to CBMH clinics was successful without needing additional funding (Taube & Quentin, Citation2020).

Furthermore, having adequate human resources was also presented as a facilitator in a multitude of papers. For the provision of high-quality CBMH treatment, it seemed essential to train professionals for their respective work. Not merely to build the needed capacity but also to convince the provider of this new treatment model (Petrea et al., Citation2020). To ensure effectiveness and practicality, it appeared beneficial to provide profession-tailored mental health training, especially if professionals have not worked with mentally-ill persons before (Hegerl et al., Citation2019; Leamy et al., Citation2014; Nicholson et al., Citation2021). The lack of human resources in EECs is displayed through a shortage of (social) workers in mental healthcare (Muijen & McCulloch, Citation2019; Petrea et al., Citation2020). It was mentioned by Muijen and McCulloch (Citation2019) that in EECs this is often a problem as there is a gap in academic expertise among the different stakeholders. On one hand, healthcare workers may lack certain skills in working with people with mental health disorders, but there is also a lack of training capacity hindering the expansion of knowledge, and the low willingness of healthcare workers to adopt new skills (Baxter & Fancourt, Citation2020; Muijen & McCulloch, Citation2019; Taube & Quentin, Citation2020). WECs face a shortage of skilled professionals in the field of mental healthcare (Baxter & Fancourt, Citation2020; Nicholson et al., Citation2021).

Lastly, having a well-structured implementation plan including a roadmap and clear responsibilities for all involved stakeholders was seen as a facilitator of successful implementation (Fieldhouse et al., Citation2017; Markström, Citation2014; Markström & Lindqvist, Citation2015; Quirke et al., Citation2020; Van Hoof et al., Citation2015). It did not appear to matter whether established structures or a new system was used, as long as factors such as reliable workflows and referral pathways, defined leadership roles, and clear milestones existed within a context-fitted framework (Fieldhouse et al., Citation2017; Petrea et al., Citation2020; Quirke et al., Citation2020; Taube & Quentin, Citation2020; Van Hoof et al., Citation2015).

Theme 3: influence of societal circumstances on the intervention

In contrast to the first two themes, which were more focused on planning and implementation factors, the third theme encompasses a variety of societal factors. The stigma around mental health disorders was mentioned in nearly all studies in both parts of Europe (de Vetten-Mc Mahon et al., Citation2019; Hegerl et al., Citation2019; Markström & Lindqvist, Citation2015; Muijen & McCulloch, Citation2019; Placella, Citation2019). This stigma posed a challenge in mental health services to be transferred to CBMH services, especially in cases where healthcare workers contribute to the discrimination of people with mental health disorders (Bażydło & Karakiewicz, Citation2016; de Vetten-Mc Mahon et al., Citation2019). Some healthcare workers even appeared to not want to work in mental healthcare because of the stigma (Placella, Citation2019; Taube & Quentin, Citation2020). Even though many of the identified CBMH services included practices to reduce stigma, it was reported that this remained an issue for implementation (Baxter & Fancourt, Citation2020; Borgi et al., Citation2019; Placella, Citation2019; Taube & Quentin, Citation2020). Although the existence of stigma was mentioned in both parts of Europe, it was mentioned as a more severe barrier to implementation in EECs (de Vetten-Mc Mahon et al., Citation2019; Placella, Citation2019; Taube & Quentin, Citation2020).

Another barrier which emerged from the papers was the distrust of society in the (mental) healthcare system. This was particularly mentioned in EECs as a contributing factor as to why CBMH interventions were difficult to implement (Bażydło & Karakiewicz, Citation2016; de Vetten-Mc Mahon et al., Citation2019; Placella, Citation2019). One reason for the difficulty in implementing the CBMH approach in Poland, Moldova, and Bosnia and Herzegovina was the overall delay in the process of deinstitutionalisation. In contrast, WECs, where mental healthcare is less focused on institutionalisation, were the first to implement CBMH activities (Bażydło & Karakiewicz, Citation2016; de Vetten-Mc Mahon et al., Citation2019; Placella, Citation2019; Wong et al., Citation2021). Due to its Soviet history, the mental healthcare system in EECs is deep-rooted in institutionalised hospital psychiatry. Therefore, the population does not trust psychiatrists and the current mental healthcare system, affecting the responsiveness to the CBMH approach (Bażydło & Karakiewicz, Citation2016; de Vetten-Mc Mahon et al., Citation2019; Placella, Citation2019).

Discussion

This systematic review of studies revealed a high variety of mostly qualitative study designs and gave an overview of 24 papers and their mentioned facilitators and barriers to successful implementation of CBMH interventions in Europe. The results of the review of current literature on CBMH interventions present that the success or failure in implementation can be attributed to three main factors: collaboration as a tool for success, the importance of sufficient resources, and community perspective on mental health. Additionally, it was seen that the experiences in Eastern and Western Europe are fairly comparable, with notable differences mostly based on the lack of commitment of stakeholders and society, and the delay in the process of deinstitutionalisation in EECs.

One of the main ideas that came through was that increasing CBMH interventions is a process that requires a full systems transition. This mirrors a growing consensus among experts that interdisciplinary teamwork and collaborations will become more common throughout the field of healthcare and mental healthcare, and that community-based services should not be excluded from this (Ponte et al., Citation2010). Apart from healthcare professionals, such interdisciplinary teams could also include non-healthcare workers such as social workers (Hegerl et al., Citation2019; Petrea et al., Citation2020; Placella, Citation2019). This is especially relevant in terms of efficient resource use, as interdisciplinary collaborations can reduce multi-treatment and could lead to successful therapy more quickly. More efficient use of resources becomes even more crucial in upcoming years, with increasing healthcare costs across all sectors and worldwide, as well as the ever-growing lack of healthcare professionals (Campbell et al., Citation2013; OECD, Citation2021). With healthcare in general becoming more individualised, this will be a challenging process. One way where intersectoral collaboration has found success in healthcare, whilst reducing the need for resources, is through the use of e-health technologies. First implementations show promising results in decreasing the health burden and being more cost-effective (Batterham et al., Citation2015; Smeets et al., Citation2014).

The findings of this literature review are by no means novel in the sphere of community-based interventions. Similar facilitators and barriers to success have also been found in community-based interventions for other health issues in Europe. In a study about a community-based programme for weight management, mentioned barriers were commitment and issues with multidisciplinary teams and mentioned facilitators were stakeholders’ recognition of the issue, sufficient resources, and practical training (Kelleher et al., Citation2017). The barriers and facilitators may be explained differently per intervention, however, they all fit in the overarching themes of this current review.

Although the abovementioned barriers and facilitators were found in both EECs and WECs, some differences could be found. As mentioned, stigma as a barrier to successful implementation was mentioned as a more notable barrier in EECs. Despite the included interventions attempting to address this in their model, it is important to note that the effectiveness of reduction of stigma is not seen on a single-level or a single-target group but has to be patient-centred to be effective (Heijnders & Van Der Meij, Citation2006). Because there is a distrust of the society in the health system in EECs, stigma is harder to reduce than in other countries and this also asks for a different approach to CBMH interventions. Using a participatory approach with community-based mental health interventions has been shown to improve the integration of CBMH interventions (Wood & Kallestrup, Citation2021). This approach focuses on the collaboration of the community stakeholders, empowering the community and having sufficient time for developing trust within the community (Wood & Kallestrup, Citation2021). Due to the distrust in the healthcare system, professionals such as social workers could serve as mediators or facilitators in this process The overarching themes regarding facilitators and barriers to implementation of CBMH interventions are applicable for both parts of Europe, however, different strategies and approaches can be made in how these are integrated into practice. As deinstitutionalisation is happening worldwide, these findings might be applicable in other regions as well (Thornicroft et al., Citation2016). However, as shown, facilitators and barriers are context-specific, and, thus, further review of CBMH interventions in other regions is needed.

This literature review should be seen in its strengths and limitations. A strength is that this is the first systematic review that gives an overview of the success factors for the integration of CBMH interventions in the whole of Europe. Furthermore, the robust systematic search is in line with the PRISMA guidelines and resulted in evidence-based and recent results. In addition, although this review does consider interregional differences, it appears that many of the findings are generalisable to the broader European area. There are however some clear limitations. The majority of the papers were based on WECs, particularly the UK. The included examples also mostly contained the views of healthcare professionals and high-level stakeholders but were lacking contribution from patients and their representatives, which potentially could add alternative perspectives on this issue. Additionally, this review contained a lot of grey literature, which contained findings resulting from expert opinions and experiences. Even though these findings had great similarities to the findings from the qualitative research, they could reflect more subjective views on the implementation.

In conclusion, the implementation of CBMH interventions and programmes is increasing worldwide to respond to the increasing burden of mental health disorders and to establish human-rights-based mental healthcare. As this is also the case in Europe, this review paper contributes to the needed knowledge on how to implement these interventions successfully while also considering differences between contexts. It was shown that factors such as cross-sectional collaborations, stakeholder commitment, adequate financial and human resources, and the perspective of the community matter. The findings from this research should be used by stakeholders, committed to the implementation of CBMH interventions, to shape their approach. Additional, comprehensive research is needed to create context-fitted programmes and improve mental healthcare in Europe.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (25.9 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam for enabling us to conduct this literature review as part of our studies, as well as for supporting the publication of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Countries include Andorra, Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, Monaco, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, San Marino, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Türkiye, United Kingdom of Britain and Northern Ireland

2 Countries include Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Georgia, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Taijkistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan

References

- American Psychological Association. (2021). APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org/community-mental-health.

- Batterham, P. J., Sunderland, M., Calear, A. L., Davey, C. G., Christensen, H., Teesson, M., Kay-Lambkin, F., Andrews, G., Mitchell, P. B., Herrman, H., Butow, P. N., & Krouskos, D. (2015). Developing a roadmap for the translation of e-mental health services for depression. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 49(9), 776–784. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867415582054

- Baxter, L., & Fancourt, D. (2020). What are the barriers to, and enablers of, working with people with lived experience of mental illness amongst community and voluntary sector organisations? A qualitative study. PloS one, 15(7). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235334

- Bażydło, M., & Karakiewicz, B. (2016). An analysis of the functioning of mental healthcare in northwestern Poland. Pomeranian Journal of Life Sciences, 62(4), 33–40. https://doi.org/10.21164/pomjlifesci.266

- Borgi, M., Marcolin, M., Tomasin, P., Correale, C., Venerosi, A., Grizzo, A., Orlich, R., & Cirulli, F. (2019). Nature-based interventions for mental health care: Social network analysis as a tool to Map social farms and their response to social inclusion and community engagement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(18), 3501. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16183501

- Campbell, J., Dussault, G., Buchan, J., Pozo-Martin, F., Guerra Arias, M., Leone, C., Siyam, A., & Cometto, G. (2013). A universal truth: No health without a workforce. Forum Report, Third global forum on human resources for health, Recife, Brazil. Geneva, Global Health Workforce Alliance and World Health Organization.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2018). CASP Checklist. CASP CHECKLISTS - CASP - Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (casp-uk.net).

- de Vetten-Mc Mahon, M., Shields-Zeeman, L. S., Petrea, I., & Klazinga, N. S. (2019). Assessing the need for a mental health services reform in Moldova: A situation analysis. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 13(45). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-019-0292-9

- Dlouhy, M., & Barták, M. (2013). Mental health financing in Six Eastern European countries. E a M: Ekonomie a Management, 16, 4–13.

- Fieldhouse, J., Parmenter, V., Lillywhite, R., & Forsey, P. (2017). What works for peer support groups: Learning from mental health and wellbeing groups in Bath and North East Somerset. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 21(1), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-11-2016-0032

- Giannakopoulos, G., & Anagnostopoulos, D. (2016). Psychiatric reform in Greece: An overview. BJPsych Bulletin, 40(6), 326–328. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.116.053652

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Hegerl, U., Maxwell, M., Harris, F., Koburger, N., Mergl, R., Székely, A., Arensman, E., Van Audenhove, C., Larkin, C., Toth, M. D., Quintão, S., Värnik, A., Genz, A., Sarchiapone, M., McDaid, D., Schmidtke, A., Purebl, G., Coyne, J. C., Gusmão, R., & OSPI-Europe Consortium (2019). Prevention of suicidal behaviour: Results of a controlled community-based intervention study in four European countries. PloS one, 14(11). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224602

- Heijnders, M., & Van Der Meij, S. (2006). The fight against stigma: An overview of stigma-reduction strategies and interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 11(3), 353–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500600595327

- Joint Action for Mental Health and Well-being. (2021). The Joint Action. https://mentalhealthandwellbeing.eu/the-joint-action/.

- Kelleher, E., Harrington, J., Shiely, F., Perry, I., & McHugh, S. (2017). Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of a community-based, multidisciplinary, family-focused childhood weight management programme in Ireland: A qualitative study. BMJ Open, 7(8), https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016459

- Knapp, M. J., McDaid, D., Mossialos, E., & Thornicroft, G. (2005). Mental health policy and practice across Europe. Open University Press.

- Krupchanka, D., & Winkler, P. (2016). State of mental healthcare systems in Eastern Europe: Do we really understand what is going on? BJPsych. International, 13(4), 96–99. https://doi.org/10.1192/S2056474000001446

- Leamy, M., Clarke, E., Le Boutillier, C., Bird, V., Janosik, M., Sabas, K., Riley, G., Williams, J., & Slade, M. (2014). Implementing a complex intervention to support personal recovery: A qualitative study nested within a cluster randomised controlled trial. PloS one, 9(5). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0097091

- Lohmeyer, F. M., Commers, M. J., Leoncini, E., Specchia, M. L., Boccia, S., Ricciardi, W. G., & de Belvis, A. G. (2019). Community-based mental healthcare: A case study in a cross-border region of Germany and The Netherlands. Gemeindebasierte Psychiatrische Versorgung in der Grenzregion Deutschlands und den Niederlanden. Gesundheitswesen (Bundesverband der Ärzte des Offentlichen Gesundheitsdienstes (Germany)), 81(3), 58–63. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0664-0579

- Markström, U. (2014). Staying the course? Challenges in implementing evidence-based programs in community mental health services. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(10), 10752–10769. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph111010752

- Markström, U., & Lindqvist, R. (2015). Establishment of community mental health systems in a postdeinstitutional Era: A study of organizational structures and service provision in sweden. Journal of Social Work in Disability & Rehabilitation, 14(2), 124–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/1536710X.2015.1014535

- Montgomery, L., Wilson, G., Houston, S., Davidson, G., & Harper, C. (2019). An evaluation of mental health service provision in Northern Ireland. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(1), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12627

- Morzycka-Markowska, M., Drozdowicz, E., & Nasierowski, T. (2015). Deinstytucjonalizacja psychiatrii włoskiej - przebieg i skutki Część II. Skutki deinstytucjonalizacji [Deinstitutionalization in Italian psychiatry - the course and consequences Part II. The Consequences of Deinstitutionalization]. Psychiatria Polska, 49(2). https://doi.org/10.12740/PP/28614

- Muijen, M., & McCulloch, A. (2019). Reform of mental health services in Eastern Europe and former Soviet republics: Progress and challenges since 2005. BJPsych International, 16(1), 6–9. https://doi.org/10.1192/bji.2017.34

- Nicholson, C., Francis, J., Nielsen, G., & Lorencatto, F. (2021). Barriers and enablers to providing community-based occupational therapy to people with functional neurological disorder: An interview study with occupational therapists in the United Kingdom. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1177/03080226211020658

- OECD. (2021). Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing.

- Patalay, P., Gondek, D., Moltrecht, B., Giese, L., Curtin, C., Stanković, M., & Savka, N. (2017). Mental health provision in schools: approaches and interventions in 10 European countries. Global Mental Health (Cambridge, England), 4, 10. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2017.6

- Pathare, S., Brazinova, A., & Levav, I. (2018). Care gap: A comprehensive measure to quantify unmet needs in mental health. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 27(5), 463–467. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796018000100

- Petrea, I. (2012). Mental health in former soviet countries: From past legacies to modern practices. Public Health Reviews, 34(5). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03391673

- Petrea, I., Shields-Zeeman, L., Keet, R., Nica, R., Kraan, K., Chihai, J., Condrat, V., & Curocichin, G. (2020). Mental health system reform in Moldova: Description of the program and reflections on its implementation between 2014 and 2019. Health Policy, 124(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.11.007

- Placella, E. (2019). Supporting community-based care and deinstitutionalisation of mental health services in Eastern Europe: Good practices from Bosnia and Herzegovina. BJPsych International, 16(1), 9–11. https://doi.org/10.1192/bji.2017.36

- Pluye, P., & Hong, Q. N. (2014). Combining the power of stories and the power of numbers: Mixed Methods Research and Mixed Studies Reviews. Annual Review of Public Health, 35, 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182440

- Ponte, P. R., Gross, A. H., Milliman-Richard, Y. J., & Lacey, K. (2010). Interdisciplinary teamwork and collaboration an essential element of a positive practice environment. Annual Review of Nursing Research, 28(1), 159–189. https://doi.org/10.1891/0739-6686.28.159

- Quirke, E., Suvalo, O., Sukhovii, O., & Zöllner, Y. (2020). Transitioning to community-based mental health service delivery: Opportunities for Ukraine. Journal of Market Access & Health Policy, 8(1), https://doi.org/10.1080/20016689.2020.1843288

- Rehm, J., & Shield, K. D. (2019). Global burden of disease and the impact of mental and addictive disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(2), 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-0997-0

- Roth, C., Wensing, M., Kuzman, M. R., Bjedov, S., Medved, S., Istvanovic, A., Grbic, D. S., Simetin, I. P., Tomcuk, A., Dedovic, J., & Djurisic, T. (2021). Experiences of healthcare staff providing community-based mental healthcare as a multidisciplinary community mental health team in Central and Eastern Europe findings from the RECOVER-E project: an observational intervention study. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1), 525. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03542-2

- Sadeniemi, M., Almeda, N., Salinas-Pérez, J. A., Gutiérrez-Colosía, M. R., García-Alonso, C., Ala-Nikkola, T., Joffe, G., Pirkola, S., Wahlbeck, K., Cid, J., & Salvador-Carulla, L. (2018). A comparison of mental health care systems in northern and Southern Europe: A service mapping study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(6), 1133. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15061133

- Sandhu, S., Priebe, S., Leavey, G., Harrison, I., Krotofil, J., McPherson, P., Dowling, S., Arbuthnott, M., Curtis, S., King, M., Shepherd, G., & Killaspy, H. (2017). Intentions and experiences of effective practice in mental health specific supported accommodation services: A qualitative interview study. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 471. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2411-0

- Smeets, O., Martin Abello, K., Zijlstra-Vlasveld, M., & Boon, B. (2014). E-health in de GGZ: hoe staat het daar nu mee? [E-health within the Dutch mental health services: what is the current situation?]. Nederlands Tijdschrift Voor Geneeskunde, 158.

- Szabzon, F., Perelman, J., & Dias, S. (2019). Challenges for psychosocial rehabilitation services in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area: A qualitative approach. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(4), 428–437. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12743

- Taube, M., & Quentin, W. (2020). Provision of community-based mental health care, Latvia. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 98(6), 426–430. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.19.239913

- Thornicroft, G., Deb, T., & Henderson, C. (2016). Community mental health care worldwide: Current status and further developments. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 15(3), 276–286. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20349

- Thornicroft, G., & Rose, D. (2005). Mental health in Europe. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 330(7492), 613–614. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.330.7492.613

- Triliva, S., Ntani, S., Giovazolias, T., Kafetsios, K., Axelsson, M., Bockting, C., Buysse, A., Desmet, M., Dewaele, A., Hannon, D., Haukenes, I., Hensing, G., Meganck, R., Rutten, K., Schønning, V., Van Beveren, L., Vandamme, J., & Øverland, S. (2020). Healthcare professionals’ perspectives on mental health service provision: A pilot focus group study in six European countries. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 14(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-020-00350-1

- Tyndall, J. (2010). AACODS Checklist. Flinders University. http://dspace.flinders.edu.au/dspace/.

- Van Hoof, F., Knispel, A., Aagaard, J., Schneider, J., Beeley, C., Keet, R., & Van Putten, M. (2015). The role of national policies and mental health care systems in the development of community care and community support: an international analysis. Journal of Mental Health, 24(4), 202–207. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2015.1036973

- Wong, B. H., Chkonia, E., Panteleeva, L., Pinchuk, I., Stevanovic, D., Tufan, A. E., Skokauskas, N., & Ougrin, D. (2021). Transitioning to community-based mental healthcare: Reform experiences of five countries. BJPsych International. https://doi.org/10.1192/bji.2021.23

- Wood, B., & Kallestrup, P. (2021). Benefits and challenges of using a participatory approach with community-based mental health and psychosocial support interventions in displaced populations. Transcultural Psychiatry, 58(2), 283–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461520983626

- World Health Organization. (2015). The European mental health action plan, 2013–2020.

- World Health Organization. (2019). Mental health. Retrieved November 18, 2021, from https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health [Accessed 18 Nov 2021].

- World Health Organization. (2021). Guidance on community mental health services: Promoting person-centred and rights-based approaches.