ABSTRACT

An important public debate in contemporary Europe is whether immigrant-origin Muslims will successfully integrate into mainstream society. We engage those debates by analysing national identification among immigrant-origin Muslim adolescents in England, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden. A common argument is that the Islamic religion prevents Muslims from integrating because its practices are incompatible with mainstream European culture. However, we find that religiosity is not the most important predictor of Muslim identification. Instead, citizenship, contact with the native majority, and perceived discrimination are all as important as religiosity for predicting Muslim national identification. In addition, we find the same relationships between these variables and national identification among Muslim and non-Muslim immigrant-origin adolescents. Country of birth, host language proficiency, and socio-economic status, by contrast, are less important predictors of national identification of both groups. In sum, our findings suggest that Muslims are not necessarily a uniquely problematic population, as their national identification is best understood through dynamics that affect immigrants more broadly rather than Muslims specifically, though more research is necessary to identify specific causal pathways.

1. Introduction

The integration of Muslims is a topic of ongoing debates Europe (Statham and Tillie Citation2016). In the public discourse and in some scholarly work, Muslims are often considered a challenge to established cultural traditions and are among the most stigmatised minority groups in Europe (cf. Cesari Citation2013; Foner and Alba Citation2008; Helbling Citation2012; Sniderman and Hagendoorn Citation2007). Integrating Muslims is a crucial task for European societies but, unfortunately, evidence suggests there is a sub-optimal cycle of Muslims being stigmatised by mainstream European society for not assimilating and Muslims withdrawing from mainstream European society because they feel rejected (Adida, Laitin, and Valfort Citation2016). This cycle may lead to ongoing Muslim alienation and does not bode well for the future of social cohesion across ethno-religious lines in Europe.

In this article, we explore the issue of Muslim integration in Europe through the lens of national identification. National identification is a key aspect of social identity (Tajfel and Turner Citation1986), and indicates a sense of belonging to the country. Shared national identification is important for social cohesion as it promotes bonds across ethnic or religious divides and helps draw distinctions between those who are in and outside of the national community (Verkuyten and Martinovic Citation2012). National identification is also a key component of minorities’ integration because it indicates the level of psychological attachment to mainstream society (Berry Citation1997; Statham and Tillie Citation2016). While many Muslims are well-integrated members of their societies who strongly identify with their European nations, in many European countries Muslims are less likely than non-Muslims to identify strongly with the nation (Fleischmann and Phalet Citation2018; Reeskens and Wright Citation2014; Schulz and Leszczensky Citation2016). Therefore, the question of what factors facilitate Muslim national identification is of urgent importance.

Understanding what drives the identification of young Muslims with their European nations is especially important, because adolescence is a crucial stage for the formation of identification with ethnic and religious groups (Umaña-Taylor et al. Citation2014). In addition, (dis-)identification of adolescent Muslims is a particular concern in Europe because of the growth in radicalisation among young Muslims (Bigo et al. Citation2014). Yet, even though there is growing interest in young European Muslims (Leiken Citation2011; Voas and Fleischmann Citation2012), we know surprisingly little about what makes them identify (or not) with their European nations. Many existing studies stress the importance of particular factors such as discrimination or exclusion (e.g. Hopkins Citation2011; Karlsen and Nazroo Citation2013). Since most such studies deal only with Muslims, however, it is difficult to assess whether related processes are specific to Muslims or part of more general patterns of the integration of ethnic and religious minorities. Large-scale survey research that compares the factors driving young Muslim and non-Muslims national identification, however, still is quite rare (see Fleischmann and Phalet Citation2018 for a recent exception).

We address this lacuna by analysing the national identification of immigrant-origin Muslim youth in four European countries. We exploit rich survey data on nationally representative samples of 15-year old second-generation immigrants in England, Germany, Sweden, and the Netherlands, provided by the Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Survey in Four European Countries (CILS4EU) project (Kalter et al. Citation2016).

Our main goal is to determine what factors are most strongly associated with national identification among European Muslim youth. Existing research suggests six main explanations for why Muslims are more (or less) likely to identify with European nations. First, Muslim religiosity is often described as a key barrier to identifying strongly with European nations. One reason for this is that Islam supposedly clashes with key European norms and values, especially among more fundamentalist adherents (Koopmans Citation2015; Sniderman and Hagendoorn Citation2007). Second, immigrant integration factors, such as having citizenship and being born in the country of destination, have been found to matter for immigrants’ national identification (Diehl and Schnell Citation2006; Karlsen and Nazroo Citation2013; Maxwell and Bleich Citation2014). Third, host language proficiency is another key determinant of ethnic and religious minorities’ national identity, as it increases feelings of similarity and cultural exchange (Hochman and Davidov Citation2014). Fourth, Muslims are often segregated into religious or ethnic minority networks with other non-European-origin minorities (Leszczensky and Pink Citation2017), and this resulting lack of contact with natives may make them less likely to identify with the nation (De Vroome, Verkuyten, and Martinovic Citation2014; Fleischmann and Phalet Citation2018). Fifth, there is a considerable degree of anti-Muslim sentiments in many European societies (Helbling Citation2014; Savelkoul et al. Citation2011; Strabac and Listhaug Citation2008). Perceived discrimination and rejection from the survey country is an important barrier to national identification among minorities, because it indicates feelings of rejection and exclusion by mainstream society (De Vroome, Verkuyten, and Martinovic Citation2014; Karlsen and Nazroo Citation2013; Schulz and Leszczensky Citation2016). Finally, socio-economic status may be important, because many Muslims in Europe are socio-economically disadvantaged (Heath, Rothon, and Kilpi Citation2014), and this lack of structural integration could hamper their national identification (Alba and Nee Citation1997; Leiken Citation2011).

Each of these explanations has different implications for the future of Muslim integration in Europe. For example, if religiosity or discrimination are critical and distinctive barriers to Muslim national identification, then there may be a fundamental enduring barrier between Muslims and mainstream European society. However, if the country of birth, citizenship, language proficiency, or contact with the native majority are the key for both Muslim and non-Muslim youth’ national identification, then Muslim integration may be best understood as a subset of broader immigrant and minority dynamics. Finally, if socio-economic status is the best predictor of Muslim identification, that would suggest the importance of structural factors that extend beyond any one ethnic, religious, or national-origin community.

Our findings indicate that the strongest predictors of Muslim identification are religiosity, citizenship, contact with the native majority, and perceived discrimination. Our results are therefore consistent with the logic that religiosity poses a challenge for Muslim integration, but we place that finding in a broader context by suggesting that other factors are equally important. Moreover, we find similar relationships among non-Muslim immigrant-origin adolescents. For example, there is also a negative relationship between religiosity and national identification among non-Muslim immigrant-origin adolescents. Likewise, majority group contact and perceived discrimination are equally important for Muslim and non-Muslim youth’ national identification, as is having citizenship. Finally, the country of birth, host language proficiency and socio-economic status were not strongly related to either Muslim or non-Muslim youth’ national identification. Taken together, our findings therefore suggest that national identification is best understood as part of dynamics that affect immigrants and minorities more broadly rather than Muslims specifically.

2. What best explains Muslim national identification?

Religion is an important source of group identity, as it consists of norms, beliefs and values that organise how people understand their place in the world (Ysseldyk, Matheson, and Anisman Citation2010). In the past decades, however, Europeans have become less likely to practice religion and increasingly likely to identify as secular or agnostic. By contrast, Muslim Europeans are much more likely than non-Muslim Europeans to be very attached to their religion (Foner and Alba Citation2008). Since Muslim parents are highly effective in transmitting their religious identities to their children (e.g. Jacob and Kalter Citation2013; Malipaard and Lubbers Citation2013; Soehl Citation2017), religiosity remains high for the descendants of Muslim immigrants as well (Voas and Fleischmann Citation2012). These higher levels of religiosity may reduce the likelihood that Muslims identify with European nation-states, because it sets them apart from societies that are largely secular.

Beyond levels of religiosity, Islam is also purported to be a barrier to national identification in Europe because of the way it is practiced. Among religiously observant Europeans, Muslims are more likely than Christians to hold fundamentalist and extremist views that separate them from the rest of society (Koopmans Citation2015; Sniderman Citation2014). Prominent examples are key social issues like gay rights and women’s rights, on which religious Muslims often have views that conflict with contemporary European norms (Hansen Citation2011; Joppke Citation2009; Sniderman and Hagendoorn Citation2007). These differing values may lead religious Muslims to consider themselves distinct from mainstream European society and therefore less likely to feel attached to the national identity.

In short, adhering to and practicing Islam is often seen as the crucial barrier to Muslims’ integration in West European societies:

H1: Muslims with higher levels of religiosity have lower levels of national identification in Europe.

Yet, a growing strand of literature questions whether religion is the best way of understanding Muslim integration in Europe (Fleischmann and Phalet Citation2018). Being a Muslim in Europe is highly correlated with being an immigrant or a descendant of recent immigrants, with being less fluent in the host language, with being segregated in ethnic minority friendship networks and neighbourhoods, and, last but not least, with socioeconomic disadvantages. Therefore, it is not clear whether religion or one of these other aspects is most crucial for understanding Muslim identity formation (Maxwell and Bleich Citation2014).

The country of birth and citizenship status may be crucial for understanding identity dynamics because they create cultural and personal connections to multiple countries and raise the possibility of competing for national allegiances (Maxwell and Bleich Citation2014; Phinney et al. Citation2006; Schulz and Leszczensky Citation2016). Country of birth is important because people who are born in a country tend to be more familiar with its customs and feel stronger attachment to its national identity (Diehl and Schnell Citation2006). Citizenship is a formal legal connection to the host society and is often associated with a greater sense of belonging and more positive identification with the host society (Ersanilli and Saharso Citation2011; Hainmueller, Hanggartner, and Pietrantuono Citation2015; Street Citation2017). These variables therefore may be crucial for predicting national identification among Muslims in Europe:

H2: Foreign-born Muslims have lower levels of national identification in Europe.

H3: Muslims with citizenship in European countries have higher levels of national identification in Europe.

Language is another key ingredient of national identity because a shared language increases feelings of similarity and cultural transmission (Phinney et al. Citation2006). Language may be especially important for minorities who have cultural origins outside the nation (e.g. most Muslims in Europe) because it is a practical way of connecting to and establishing similarities with mainstream society (Alba and Nee Citation1997). Moreover, having more proficiency in the host country language increases ethnic minority members’ similarity with the native-origin population, which should result in stronger attachment to the society. Existing research has documented these connections between linguistic and broader cultural similarities across a range of groups and countries (De Vroome, Verkuyten, and Martinovic Citation2014; Hochman and Davidov Citation2014; Phinney et al. Citation2006; Schulz and Leszczensky Citation2016). This generates the following hypothesis:

H4: Muslims who are proficient in the host country language have higher levels of national identification in Europe.

Ethnic and religious segregation of social and residential networks and a respective lack of contact with native majority group members is another potential lens for understanding Muslim identification in Europe. Research has shown that adolescent Muslims tend to have religiously and ethnically segregated friendship networks (Leszczensky and Pink Citation2017). In addition, many Muslims in Europe live in neighbourhoods with low shares of non-Muslim and non-co-ethnic residents (Phillips Citation2010; Semyonov and Glikman Citation2009). Segregation may inhibit Muslim national identification by limiting Muslims’ exposure and connection to mainstream society (Ersanilli and Saharso Citation2011; Schulz and Leszczensky Citation2016), or by exacerbating Muslims’ feelings of exclusion (De Vroome, Verkuyten, and Martinovic Citation2014; Leszczensky Citation2013; Phinney et al. Citation2006). Therefore, the extent to which Muslims are enmeshed in ethnically and religiously segregated social and residential networks and lack contact with the native majority group may affect the strength of their national identification:

H5: Muslims with less contact with native majority group members have lower levels of national identification in Europe.

A considerable degree of Europeans holds negative attitudes towards Muslims (Helbling Citation2014; Savelkoul et al. Citation2011; Strabac and Listhaug Citation2008). Many studies have shown that minority group members who perceived discrimination identify less strongly with their nations (Badea et al. Citation2011; Jasinskaja-Lahti, Liebkind, and Solheim Citation2009; Maxwell Citation2009; Verkuyten and Yildiz Citation2007). Accordingly, European Muslims national identification might be hampered by perceived discrimination:

H6: Muslims who perceive discrimination have lower levels of national identification in Europe.

Finally, the development of Muslim youths’ national identification might be hampered by low socio-economic status. This line of thinking builds on the fact that Muslims are overrepresented among Europe’s socio-economically disadvantaged residents, in large part because they arrived as low-skilled guest-workers or immigrants in search of low-skilled jobs (Otterbeck and Nielsen Citation2016). This unfavourable socioeconomic background also explains most of the ethnic and religious inequalities that children of immigrants face in European educational systems and labour markets (Heath, Rothon, and Kilpi Citation2014). Socioeconomic success is often considered as a crucial condition for feeling included in society (Alba and Nee Citation1997), and socio-economic disadvantages can lead to alienation from mainstream society and therefore lower levels of national identification (De Vroome, Verkuyten, and Martinovic Citation2014). This generates the following hypothesis:

H7: Muslims with worse socio-economic outcomes have lower levels of national identification in Europe.

3. Data and measures

3.1 Data

We use data from the project Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Survey in Four European Countries (CILS4EU; Kalter et al. Citation2016). The CILS4EU data are nationally representative samples of immigrant-origin children as well as native-origin reference groups in England, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden. We use the first wave of the CILS4EU data, which was collected during the academic year 2010–2011 and surveyed 15-year old adolescents.

In the first wave of CILS4EU the youth completed a written questionnaire in high schools; students who were ill or otherwise absent received a questionnaire at home. Cognitive pretests and pilot studies in all four countries were conducted to develop standardised and comparable measures. To achieve a large sample of adolescents with an immigration background, schools with higher proportions of immigrant-origin students were oversampled. Within these schools, at least two school classes were randomly selected and all students in these classes were surveyed. Students’ parents were also interviewed, and parental questionnaires were available in nonnative languages as well. If parents did not respond, reminders were sent and parents were contacted via phone. In total, 18,716 students in 958 classes completed the survey. A total of 11,700 parents returned a completed questionnaire or participated via phone.

Our analysis focuses on Muslim youth who were born abroad or had at least one parent born abroad. We focus on immigrant-origin Muslim youth because the overwhelming majority of Muslims in Europe (97 percent of our sample) are either immigrants or children of immigrants. Excluding students with missing information on our key variables defined below results in 2,133 immigrant-origin Muslim adolescents.

3.2 Measures

Our dependent variable national identification is captured by students’ answer to the question ‘How strongly do you feel British/German/Dutch/Swedish’. Students ranked themselves on a four-point scale, ranging from ‘not at all strongly’ to ‘very strongly’. Similar measurements were used in earlier large-scale studies on national identification (Fleischmann and Phalet Citation2018; Leszczensky Citation2013; Maxwell and Bleich Citation2014).

The CILS4EU data provide a rich range of indicators for our hypotheses. To simplify the comparisons across hypotheses we use factor analysis to construct latent variables for religiosity, and contact with natives, as we have several indicators for each of these factors. Being foreign-born and holding citizenship are dummy variables that indicate whether students were born outside of the survey country and, respectively, hold citizenship of the survey country. Language, perceived discrimination, and socio-economic status are captured by metric scales (described below) that capture the respective latent construct. We recode all factor variables to values between 0 and 1. Details on all variables are found in section A of the appendix.Footnote1

Students’ religiosity is captured by the questions ‘How important is religion to you?’ and ‘How often do you pray?’Footnote2 Language proficiency is measured by a language ability test that captured verbal competencies in the language of the survey country, by using synonym- or antonym-tests (CILS4EU Citation2016, 40f.). Majority contact is captured by the self-assessed share of native-origin friends and neighbours. Perceived discrimination is measured by how often the respondent felt discriminated against or treated unfairly in four contexts: in school, in trains/buses/trams/subway, in shops/stores/cafes/restaurants/nightclubs, or by police or security guards. Finally, socio-economic status is based on the highest parental value of the interval-scale ISEI-08 occupational status (Ganzeboom Citation2010). Students provided information on the occupation of both parents, and this has been found to be a reliable measure (Engzell and Jonsson Citation2015).

Higher values on the 0–1 scale for each variable indicate higher religiosity, more integration, better language proficiency, more contact with natives, and higher socio-economic status. In addition, country dummies indicate the country of settlement. Table B1 in the appendix provides mean values and standard deviations for all variables pooled over the four countries as well as for the individual countries.

4. Results

4.1 Putting Muslim national identification into context

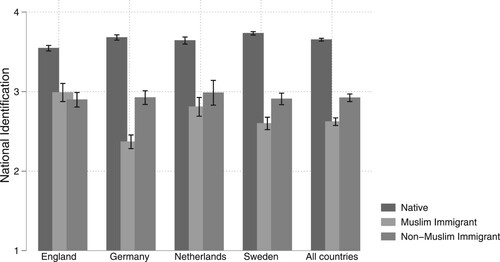

displays weighted mean values of national identification of immigrant-origin Muslims in the pooled sample of all four survey countries as well as across each of the four individual countries. For sake of comparison, native-origin youth and immigrant-origin non-Muslims with a religious affiliation are also displayed. The former ones are defined as students who were born in the survey country to two parents born in the country and who did not identify themselves as Muslims, the latter ones as immigrant-origin youth with a religious affiliation other than Muslim.

Figure 1. Mean Values of National Identification among Youth in England, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden.

Source: CILS4EU, wave 1, weighted, full sample.

In the pooled sample of all four countries, immigrant-origin youth national identification is considerably weaker than those of their native peers. This pattern holds in each of the four countries. Averaged across all four countries, Muslim youth also identify less strongly with their countries of residence than their non-Muslim immigrant-origin peers. As the country-specific bars show, this pattern holds in all countries but England.

4.2 What are the most important predictors of immigrant-origin Muslim youth national identification?

To assess the relative importance of religiosity, being foreign-born, holding citizenship, language, majority contact, perceived discrimination, and socioeconomic status, we estimate a series of linear OLS regression models predicting national identification of immigrant-origin Muslim youth. Each model includes one of these factors as well as country dummies for the country of settlement; a final model includes all five factors. We estimate the model for the pooled sample of all four countries, using sampling weights and clustered standard errors.Footnote3 shows the results.

Table 1. OLS Regression Models of National Identification of Immigrant-Origin Muslims in Four European Countries.

M1 in shows that in line with hypothesis 1, religiosity is negatively related to Muslim youth national identification. M2 and M7 further support hypotheses 2, 3, 4, and 6, showing that Muslim youth who were born in the settlement country, who are citizens, who have many native friends and neighbours, and who perceive discrimination less often identify more strongly with their European nations. By contrast, M4 and M7 show that contrary to hypotheses 4 and 7, Muslim youth who are more fluent in the host language and who have a higher socio-economic status (SES) do not have higher levels of national identification than those who are less fluent and have a lower SES.

M8 shows that considering all factors within a single model does not considerably change their respective coefficients obtained from the individual models. Substantively, the full model indicates that Muslims with the highest possible religiosity score identified more than third a scale-point less with their European nations than those with the lowest possible religiosity score. However, religiosity is neither uniquely powerful, nor the most powerful predictor of national identification. The association between holding citizenship, majority contact, and perceived discrimination and national identification are similar to the relationship between religiosity and identification. In fact, Muslim youth who have the most contact with native majority group members or who perceive the least amount of discrimination identify about half a scale-point more with their European nation than those with the least contact with natives or the highest amount of perceived discrimination, making both factors the single largest predictors.

These results suggest that while higher religiosity scores correlate with lower national identification, national identification dynamics among Muslims adolescents are also explained by broader processes of majority group contact, perceived discrimination, country of birth, and citizenship affecting minorities and immigrants more generally rather than by challenges unique to religious Muslims.

4.3 Comparison with non-Muslim immigrant-origin youth

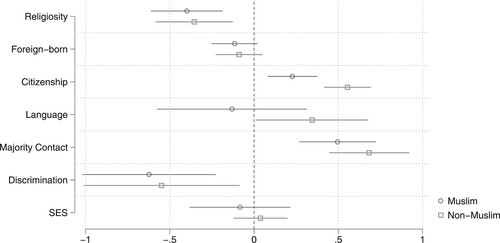

To place Muslim identification dynamics in a broader perspective, we now turn to the predictors of non-Muslim national identification. We re-estimate the full regression model (M8) from for immigrant-origin youth with a non-Muslim religious affiliation. If Muslim and non-Muslim youth have similar relationships between religiosity, being foreign-born, holding citizenship, language, majority contact, perceived discrimination, and socio-economic status, that would be further evidence that Muslim national identification dynamics are best understood as part of broader processes affecting immigrants and minorities rather than factors specific to Islam and Muslims. compares the average marginal effects obtained from this model with those obtained for Muslim youth in . The full model is found in Table C1 in the appendix.

Figure 2. Average Marginal Effects on Muslim and Non-Muslim Immigrants-Origin Youth’ National Identification.

Source: CILS4EU, wave 1, weighted, 95% confidence interval. Prediction based on full model in the pooled sample.

indicates that most associations are very similar for Muslim and non-Muslim immigrant-origin youth. In fact, only the coefficients for citizenship and language statistically differ between both groups. Citizenship is positively associated with both Muslim and non-Muslim youth’ national identification, but this relationship is slightly more pronounced for non-Muslims (p < 0.05). By contrast, while host language proficiency is not related to Muslim youth identification, it is positively related to that of non-Muslims, although the difference between the two coefficients is statistically significant only at the ten percent level (p < 0.1).

In sum, these relationships suggest that Muslim national identification is not a unique dynamic. In fact, the basic patterns thus are remarkably similar for both groups: religiosity, holding citizenship, majority contact, and perceived discrimination seem to be the most important predictors of national identification, and socio-economic status the least important one. Significantly, the religiosity variable has a similar magnitude and direction for both Muslim and non-Muslim youth. This offers strong support to the argument that national identification is primarily a function of general factors affecting immigrants and minorities, rather than of factors specific to practicing Muslims.

This argument is further supported by additional analyses regarding the difference in the strength of national identification between Muslim and non-Muslim immigrant-origin youth showed in . As shown in Table D1 in the appendix, and mirroring , Muslim youth identified less strongly than non-Muslim immigrant-origin youth with their European nations. A series of regression models each including a single predictor shows that no single predictor alone accounts for this gap in identification (also see Fleischmann and Phalet Citation2018). Consistent with the results presented above, religiosity, citizenship, majority and perceived discrimination turned out not only to be the most important predictors for explaining immigrant-origin youth’ national identification but also for explaining the difference in identification between Muslim and non-Muslim youth.

4.4 Heterogeneity among Muslims?

Our previous analyses analysed all Muslims together but European Muslims are far from a homogenous group. One important source of heterogeneity is region of origins, as European and non-European origin Muslim immigrants may face different identification dynamics. To address this, we restimated the full model (M8) from for Muslims of European and non-European descent separately. The result in Figure E1 in the appendix shows that the general associations observed earlier are remarkably similar for both kinds of Muslims. Another important source of heterogeneity is whether or not Muslims are the dominant Muslim group in the host country. For example, much of the debate around Islam in Germany is dominated by issues related to Turkish Muslims but dynamics may be different for non-Turkish-origin Muslims. Therefore, we restimated the full model separately for Muslims from the dominant and non-dominant countries of origin within the four countries. Figure E2 in the appendix indicates that this distinction does not matter as the relationships for both groups of Muslims again are very similar.

4.5 Do the results hold for all four countries?

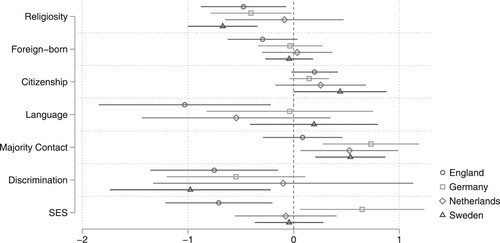

We have presented results for the pooled sample of England, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden. However, Muslim identification dynamics may vary across these four countries, because national contexts of immigrant integration and religious institutions shape the political and social integration of Muslims in Europe (e.g. Ersanilli and Saharso Citation2011; Fleischmann and Phalet Citation2018; Koopmans et al. Citation2005). shows that Muslims in Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden have lower levels of national identification than Muslims in England. In fact, it is well-established that British Muslims report high levels of national identification (Maxwell Citation2006; Nandi and Platt Citation2015), but that Muslims in several other Western European countries are less likely than non-Muslims to identify strongly with the nation (Fleischmann and Phalet Citation2018; Reeskens and Wright Citation2014; Schulz and Leszczensky Citation2016). Therefore, we again estimate the full model (M8) from , but this time separately for Muslim immigrant-origin youth in each of the four countries. The results are illustrated in , which shows the average marginal effect of each factor for every country. The respective country-specific regression tables are found in section F of the appendix.

Figure 3. Average Marginal Effects on Muslim Immigrants-Origin Youth’ National Identification Separated for Each Country.

Source: CILS4EU, wave 1, weighted, 95% confidence interval. Predictions based on full model for each country.

The country-specific models support most of the conclusions of the earlier analysis of the pooled sample. For the most part, each independent variable has similar relationships with national identification across the four countries.Footnote4 In addition, contact with the native majority group has a strong positive relationship with national identification in each country but England, and perceived discrimination has a strong negative relationship with national identification in each country but the Netherlands. This suggests that Muslim adolescents have roughly similar identification dynamics across the four countries and in each country the national identification dynamics among Muslims adolescents may be best explained by broader processes related to immigrants and minorities.

5. Conclusions

The integration of young Muslims will affect Europe for decades to come. Public debates often contend that Muslim-specific factors such as high religiosity are a key barrier to their identification with their European nations. If true, the persistence of high religiosity among Muslims would be a serious hurdle to the social coherence in European societies. This would be even more problematic if adolescents’ religiosity were a decisive factor, as adolescents are an especially sensitive segment of the population because of their potential to be alienated or even radicalised (Bigo et al. Citation2014; Leiken Citation2011).

Our study addresses these issues through the examination of national identification dynamics among Muslim and non-Muslim adolescents in England, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden. Our results reveal that the factors that affect Muslim national identification are very similar to those that affect non-Muslim immigrant-origin youth. Even religiosity, which is commonly conceived as a variable posing specific challenges with respect to Muslim integration, was also negatively related to non-Muslim youth national identification. Moreover, for both Muslim and non-Muslim immigrants, holding citizenship and especially contact with the native majority group and perceived discrimination are equally or more important than levels of religiosity. In contrast, the country of birth, host language proficiency and socio-economic status are less important predictors of Muslim and non-Muslim youth’ national identification under most circumstances. These results are consistent with the analysis of France in Maxwell and Bleich (Citation2014), although we broaden their findings to a wider range of countries and a different (adolescent) sample population.

Our results have several implications for understanding the integration of young Muslims in European societies. On the one hand, our finding of a strong positive relationship between citizenship status and national identification is a promising indication that Muslim integration may be likely to improve over time as more immigrant-origin Muslims become citizens of their European host countries. Admittedly, we cannot control for the fact that Muslims with strong national identification may be more likely to receive host country citizenship. Future research should explore this more closely. However, our results are consistent with other recent research suggesting that the negative portrayals of Muslim integration may be biased by a focus on the dramatic outliers, and do not capture the broader positive trends for Muslim youth in Europe (Kashyap and Lewis Citation2013). Moreover, to the extent that Muslim and non-Muslim identification dynamics are similar, it suggests that Muslim integration may not be as uniquely problematic as some believe.

On the other hand, our results also provide clear evidence of a negative association between immigrant-origin youth religiosity and national identification. Yet, this relationship was similar for Muslim and non-Muslim youth, which indicates that religiosity may be a general brake to strong national identification of minority youth in Europe instead of a Muslim-specific factor. Echoing earlier research (Voas and Fleischmann Citation2012), however, it is important to note that Muslim youth in the four countries were, on average, much more religious than non-Muslim ones, and that unlike for Christians, this pattern of high religiosity is remarkably constant across generations of European Muslims (Jacob and Kalter Citation2013; Soehl Citation2017). Our findings suggest that this particularly high religiosity among Muslims has important ramifications for their national identification, even though its role does not generally differ from those for non-Muslims.

An important limitation of our study is that we are not able to identify specific causal pathways. For example, high levels of religiosity might prevent Muslim youth from befriending natives (Leszczensky and Pink Citation2017; Maliepaard and Phalet Citation2012), and this lack of contact with natives may in turn hamper the development of national identification (Leszczensky Citation2013). On the other hand, Muslim youth who do not identify with their European nations may turn to their religion as a source of social identification, so that the causal link might run from identification to religiosity rather than the other way around. Similar challenges exist for specifying the relationship between perceived discrimination and identification. Unfortunately, disentangling causal relationships is very difficult, if not impossible, with observational data such as the CILS4EU survey. Teasing out the different causal pathways therefore is an important task for future studies.

In sum, our results address some of the most prominent scholarly debates and public discussions in Europe today by suggesting that religiosity may not be the most distinctive or important factor related to Muslim adolescents’ lower attachment to European national identities. In addition, we find similar relationships affecting national identification for Muslim and non-Muslim adolescents. This suggests both that Islam is not unique compared to other immigrant religions, and that the degree to which Muslim youth identify with their European nations will likely increase when integration along other dimensions advances.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (472 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 We also conducted analyses with individual measures of each hypothesis, the results of which were similar.

2 We also reran the main analysis using separate measures of religiosity (importance of religion and frequency of prayer). The results were very similar; we prefer the combined measure, though, as it allows for more fine-grained distinctions of, especially, Muslims religiosity. The results also very robust to including a set of dummy variables rather than a score for assessing religiosity.

3 Sampling weights were provided by CILS4EU to correct for different selection probabilities and to obtain correct estimates of population characteristics (CILS4EU Citation2016, 33ff.). We calculated clustered standard errors to account for the fact that students were surveyed via, and thus nested in, school classes. Taking into account that our four-point scale of national identification is not strictly metric, we also estimated ordered logistic regression models. The conclusions were the same as with OLS, but the Brant test was violated. We therefore present the OLS results, which are also easier to interpret, especially when comparing different groups or models.

4 England is the exception, where majority contact is not associated with national identification, and better socio-economic status and stronger fluency in the host country language are negatively so. It is beyond the scope of this article (and these data) to tease out a full explanation for this divergence, but it is worthy of future study. In general, England is a special case, given that unlike their co-religionists in Germany or the Netherlands, British Muslims have high levels of British identification (e.g., Karlsen and Nazroo Citation2015; Maxwell Citation2006; Nandi and Platt Citation2015). These high levels of national identification may be due to the fact that many Muslims are from countries that were part of the British empire and have a long history of identifying with Britain. In addition, “British” is a broad imperial multi-ethnic identity that does not have the same exclusive connotation as English, German, or Swedish.

References

- Adida, C., D. D. Laitin, and M. A. J. Valfort. 2016. Why Muslim Integration Fails in Christian-Heritage Societies. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Alba, R., and V. Nee. 1997. “Rethinking Assimilation Theory for a New Era of Immigration.” International Migration Review 31: 826–874. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/019791839703100403

- Badea, C., J. Jetten, A. Iyer, and A. Er-rafiy. 2011. “Negotiating Dual Identities: The Impact of Group-Based Rejection on Identification and Acculturation.” European Journal of Social Psychology 41: 586–595. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.786

- Berry, J. 1997. “Immigration, Acculturation, and Adaptation.” Applied Psychology 46: 5–34.

- Bigo, D., L. Bonelli, E.-P. Guittet, and F. Ragazzi. 2014. Preventing and countering youth radicalization in the EU. Directorate-General for Internal Policies, European Parliament.

- Cesari, J. 2013. Why the West Fears Islam: An Exploration of Muslims in Liberal Democracies. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- CILS4EU. 2016. Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Survey in Four European Countries. Technical Report. Wave 1–2010/2011, v1.2.0. Mannheim: Mannheim University.

- De Vroome, T., M. Verkuyten, and B. Martinovic. 2014. “Host National Identification of Immigrants in the Netherlands.” International Migration Review 48: 76–102. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12063

- Diehl, C., and R. Schnell. 2006. ““Reactive Ethnicity” or “Assimilation”? Statements, Arguments, and First Empirical Evidence for Labor Migrants in Germany.” International Migration Review 40: 786–816. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2006.00044.x

- Engzell, P., and J. O. Jonsson. 2015. “Estimating Social and Ethnic Inequality in School Surveys: Biases From Child Misreporting and Parent Nonresponse.” European Sociological Review 31: 312–325. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcv005

- Ersanilli, E., and S. Saharso. 2011. “The Settlement Country and Ethnic Identification of Children of Turkish Immigrants in Germany, France, and the Netherlands: What Role do National Integration Policies Play?” International Migration Review 45: 907–937. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2011.00872.x

- Fleischmann, F., and K. Phalet. 2018. “Religion and National Identification in Europe: Comparing Muslim Youth in Belgium, England, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 49: 44–61. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022117741988

- Foner, N., and R. Alba. 2008. “Immigrant Religion in the U.S. and Western Europe: Bridge or Barrier to Inclusion?” International Migration Review 42: 360–392. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2008.00128.x

- Ganzeboom, H. B. 2010. International Standard Classification of Occupations ISCO-08 with ISEI-08 Scores, Version of July 27 2010, available from: http://www.harryganzeboom.nl/isco08/isco08_with_isei.pdf, accessed 5 December 2016.

- Hainmueller, J., D. Hanggartner, and G. Pietrantuono. 2015. “Naturalization Fosters the Long-Term Political Integration of Immigrants.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 112: 12651–12656. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1418794112

- Hansen, R. 2011. “The Two Faces of Liberalism: Islam in Contemporary Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37: 881–897. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2011.576192

- Heath, A. F., C. Rothon, and E. Kilpi. 2014. “The Second Generation in Western Europe: Education, Unemployment, and Occupational Attainment.” Annual Review of Sociology, 211–235.

- Helbling, M. 2012. Islamophobia in the West Measuring and Explaining Individual Attitudes. Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

- Helbling, M. 2014. “Opposing Muslims and the Muslim Headscarf in Western Europe.” European Sociological Review 30: 242–257. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jct038

- Hochman, O., and E. Davidov. 2014. “Relations between Second-Language Proficiency and National Identification: the Case of Immigrants in Germany.” European Sociological Review 30: 344–359. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcu043

- Hopkins, N. 2011. “Dual Identities and Their Recognition: Minority Group Members’ Perspectives.” Political Psychology 32: 251–270. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00804.x

- Jacob, K., and F. Kalter. 2013. “Intergenerational Change in Religious Salience among Immigrant Families in Four European Countries.”.” International Migration 51: 38–56. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12108

- Jasinskaja-Lahti, I., K. Liebkind, and E. Solheim. 2009. “To Identify or not to Identify? National Disidentification as an Alternative Reaction to Perceived Ethnic Discrimination.” Applied Psychology 58: 105–128. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00384.x

- Joppke, C. 2009. “Limits of Integration Policy: Britain and her Muslims.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35: 453–472. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830802704616

- Kalter, Frank, et al. 2016. Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Survey in Four European Countries (CILS4EU) – Reduced version. Reduced data file for download and off-site use. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne, ZA5656 Data file Version 1.2.0, doi:https://doi.org/10.4232/cils4eu.5656.1.2.0.

- Karlsen, S., and James Y Nazroo. 2013. “Influences on Forms of National Identity and Feeling ‘at Home’ among Muslim Groups in Britain, Germany and Spain.” Ethnicities 13: 689–708. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796812470795

- Karlsen, S., and James Y Nazroo. 2015. “Ethnic and Religious Differences in the Attitudes of People Towards Being ‘British’.” The Sociological Review 63: 759–781. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12313

- Kashyap, R., and V. Lewis. 2013. “British Muslim Youth and Religious Fundamentalism: a Quantitative Investigation.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 36: 2117–2140. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2012.672761

- Koopmans, R. 2015. “Religious Fundamentalism and Hostility Against out-Groups: a Comparison of Muslims and Christians in Western Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41: 33–57. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2014.935307

- Koopmans, R., P. Statham, M. Giugni, and F. Passy. 2005. Contested Citizenship. Immigration and Cultural Diversity in Europe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Leiken, R. 2011. Europe's Angry Muslims: The Revolt of the Second Generation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Leszczensky, L. 2013. “Do National Identification and Interethnic Friendships Affect one Another? A Longitudinal Test with Adolescents of Turkish Origin in Germany.” Social Science Research 42: 775–788. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.12.019

- Leszczensky, L., and S. Pink. 2017. “Intra- and Inter-Group Friendship Choices of Christian, Muslim, and non-Religious Adolescents in Germany.” European Sociological Review 33: 72–83.

- Maliepaard, M., and K. Phalet. 2012. “Social Integration and Religious Identity Expression among Dutch Muslims the Role of Minority and Majority Group Contact.” Social Psychology Quarterly 75: 131–148. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272511436353

- Malipaard, M., and M. Lubbers. 2013. “Parental Religious Transmission after Migration: the Case of Dutch Muslims.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39: 425–442. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2013.733862

- Maxwell, R. 2006. “Muslims, South Asians and the British Mainstream: A National Identity Crisis?” West European Politics 29 (4): 736–756. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380600842312

- Maxwell, R. 2009. “Caribbean and South Asian Identification with British Society: the Importance of Perceived Discrimination.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 32 (8): 1449–1469. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870802604024

- Maxwell, R., and E. Bleich. 2014. “What Makes Muslims Feel French?” Social Forces 93: 342–353. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sou064

- Nandi, A., and L. Platt. 2015. “Patterns of Minority and Majority Identification in a Multicultural Society.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38: 2615–2634. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2015.1077986

- Otterbeck, J., and J. Nielsen. 2016. Muslims in Western Europe. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press.

- Phillips, D. 2010. “Minority Ethnic Segregation, Integration and Citizenship: a European Perspective.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36: 209–225. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830903387337

- Phinney, J. S., J. W. Berry, P. Vedder, and K. Liebkind. 2006. “The Acculturation Experience: Attitudes, Identities and Behaviors of Immigrant Youth.” In Immigrant Youth in Cultural Transition: Acculturation, Identity, and Adaptation Across National Contexts, edited by J. W. Berry, J. S. Phinney, D. L. Sam, and P. Vedder, 71–116. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum.

- Reeskens, T., and M. Wright. 2014. “Host-country Patriotism among European Immigrants: A Comparative Study of its Individual and Societal Roots.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37: 2493–2511. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2013.851397

- Savelkoul, M., P. Scheepers, J. Tolsma, and L. Hagendoorn. 2011. “Anti-Muslim Attitudes in the Netherlands: Tests of Contradictory Hypotheses Derived from Ethnic Competition Theory and Intergroup Contact Theory.” European Sociological Review 27: 741–758. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcq035

- Schulz, B., and L. Leszczensky. 2016. “Native Friends and Host Country Identification among Adolescent Immigrants in Germany: the Role of Ethnic Boundaries.” International Migration Review 50: 163–196. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12163

- Semyonov, M., and A. Glikman. 2009. “Ethnic Residential Segregation, Social Contacts, and Anti-Minority Attitudes in European Societies.” European Sociological Review 25: 693–708. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcn075

- Sniderman, Paul, et al. 2014. Paradoxes of Liberal Democracy: Islam, Western Europe, and the Danish Cartoon Crisis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Sniderman, P., and L. Hagendoorn. 2007. When Ways of Life Collide. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Soehl, T. 2017. “Social Reproduction of Religiosity in the Immigrant Context: the Role of Family Transmission and Family Formation–Evidence From France.” International Migration Review 51: 999–1030. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12289

- Statham, P., and J. Tillie. 2016. “Muslims in Their European Societies of Settlement:a Comparative Agenda for Empirical Research on Socio-Cultural Integration Across Countries and Groups.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42: 177–196. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2015.1127637

- Strabac, Z., and O. Listhaug. 2008. “Anti-Muslim Prejudice in Europe: A Multilevel Analysis of Survey Data from 30 Countries.” Social Science Research 37: 268–286. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2007.02.004

- Street, A. 2017. “The Political Effects of Immigrant Naturalization.” International Migration Review 51: 323–343. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12229

- Tajfel, H., and J. C. Turner. 1986. “The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior.” In Psychology of Intergroup Relations, edited by S. Worchel, and W. G. Austing, 7–24. Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

- Umaña-Taylor, A. J., S. M. Quintana, R. M. Lee, W. E. Cross, JR, D. Rivas-Drake, S. J. Schwartz, M. Syed, T. Yip, and E. Seaton. 2014. “Ethnic and Racial Identity During Adolescence and Into Young Adulthood: An Integrated Conceptualization.” Child Development 85: 21–39. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12196

- Verkuyten, M., and B. Martinovic. 2012. “Immigrants’ National Identification: Meanings, Determinants, and Consequences.” Social Issues and Policy Review 6: 82–112. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-2409.2011.01036.x

- Verkuyten, M., and A. A. Yildiz. 2007. “National (dis)Identification and Ethnic and Religious Identity: a Study among Turkish-Dutch Muslims.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 33: 1448–1162. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167207304276

- Voas, D., and F. Fleischmann. 2012. “Islam Moves West: Religious Change in the First and Second Generations.” Annual Review of Sociology 38: 525–545. doi: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071811-145455

- Ysseldyk, R., K. Matheson, and H. Anisman. 2010. “Religiosity as Identity: Toward an Understanding of Religion From a Social Identity Perspective.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 14: 60–71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868309349693