ABSTRACT

Migrant integration is an issue at the forefront of political debates in many immigrant-receiving countries. Within academia, a rich body of neighbourhood effects literature examines the significance of the residential environment for the socioeconomic integration of international migrants. Another strand of research explores the associations between immigrants’ initial region of residence and their subsequent socioeconomic integration. Existing research focuses on a single dimension of geographical context and on the neighbourhood scale. Using Swedish longitudinal register data, we estimate discrete-time event history models to assess how regional and neighbourhood contexts influence refugees’ entry into employment. Our study includes all refugees who arrived in Sweden between 2000 and 2009, distinguishing between three categories of refugees: refugees with assigned housing, refugees with self-arranged housing and quota refugees. Our results reveal a clear pattern where the most advantageous regions for finding a first employment are those at the extremes of the population density distribution: the Stockholm region and small city/rural regions. Refugees residing in Malmö have the lowest probability of entering the labour market. Our study also reiterates existing concerns regarding the negative effects of ethnic segregation at the neighbourhood level on labour market participation.

Introduction

Migrant integration is an issue at the forefront of political and academic debates in many immigrant-receiving countries. It has become particularly prominent in Sweden, as the country recently experienced a high influx of refugees, mainly coming from conflict-affected areas in Syria and Afghanistan. A record was reached in 2015 when 160,000 individuals applied for asylum.

Within academia, the significance of the residential environment for the socioeconomic integration of international migrants is analysed in a rich body of neighbourhood effects literature. In the Swedish context, some studies have found that residence in deprived neighbourhoods hampers immigrants’ employment and income prospects (Musterd et al. Citation2008; Wimark, Haandrikman and Nielsen Citation2019), while other studies highlight the positive effects of immigrant concentration (Edin, Fredriksson, and Åslund Citation2003; Andersson and Hammarstedt Citation2015). A parallel strain of research explores the associations between immigrants’ initial place of residence and their subsequent socioeconomic integration. Studies that analyse the effects of residential context usually focus on neighbourhoods, small geographical areas typically corresponding to census tracts. The regional level, however, deserves more attention, especially in relation to labour market participation. Regions are indeed larger geographical units that tend to coincide with local labour market areas, which makes them more suitable for the analysis of labour market dynamics. Moreover, existing research tends to focus on a single dimension of geographical context, such as immigration density or labour market conditions. Thus, there is a need for further research that jointly investigates multiple dimensions of migrants’ geographical context.

The aim of this study is to explore the relationship between residential context and the transition into first employment in the case of refugees who arrived in Sweden during the 2000s. Using rich Swedish longitudinal register data, we follow refugees over a nine-year period. First, we describe differences in timing to first employment for various groups in our study population. Second, we estimate discrete-time event history models in order to assess how residential context influences refugees’ entry into employment.

The paper contributes to the existing literature through its focus on multiple dimensions of the regional context, including population density and labour market conditions. It also employs an innovative method to measure the neighbourhood context based on individual-centred neighbourhoods (Östh, Malmberg, and Andersson Citation2014). Understanding the relationship between refugees’ residential context and their employment prospects is highly relevant to current policy debates in Sweden. In recent years, concerns over high levels of residential segregation and overcrowding among newly arrived migrants have prompted new criticisms against the asylum seekers’ freedom to settle where they want. A special committee (Mottagandeutredningen) was appointed by the government to develop proposals for reforming refugee reception. The committee’s report, published in March 2018, suggests the re-introduction of restrictions to the freedom of asylum seekers to arrange for their own accommodation in municipalities with socioeconomically disadvantaged neighbourhoods (SOU Citation2018, 41).

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: After a short outline of the labour market situation of refugees in Sweden, the theoretical and empirical background on the relationship between residential context and migrant integration is presented; in Data and Methods, we describe our data material and introduce the method of event history analysis; the Results section reports descriptive and regression results; and we conclude with a discussion of our findings, policy considerations, and directions for further research.

Refugees in the Swedish labour market

After having been a country of emigration in the 19th and early 20th centuries, Sweden became a country of immigration after World War II. Initially, refugees arriving to Sweden came from neighbouring countries, mainly from Finland. From the 1970s onwards, inflows have consisted of non-European political refugees from the Middle East, Latin America and the Horn of Africa. The Balkan wars in the 1990s caused a new inflow of refugees from the former Yugoslavia. The war in Iraq in 2003 and the ongoing conflicts in Syria and Afghanistan have also led to large inflows from these countries.

Sweden is renowned for its extensive welfare system and its support for migrant integration programmes. Historically, Swedish integration policy has been defined by its adherence to principles of diversity and multiculturalism (Wiesbrock Citation2011). In recent years, integration policy has increasingly focused on socioeconomic inclusion. Newly arrived migrants are eligible for an ‘establishment plan’ with the Employment Service, which includes Swedish language classes, basic information on the Swedish society and activities to facilitate labour market integration.

Despite Sweden’s support for integration policy, migrants in Sweden have considerably lower labour market participation than natives. In 2017, the employment gap between migrants and natives amounted to 13.6%, which was among the highest in OECD countries (OECD Citation2018a, Citation2018b). Refugees are in a particularly vulnerable position. Only 70% of male refugees and 65% of female refugees are gainfully employed ten years after their arrival (Irastorza and Bevelander Citation2017). There are also differences by region of origin, with individuals from Iraq and the Horn of Africa being less likely to be employed (Bevelander Citation2011; Irastorza and Bevelander Citation2017).

Migrants are also overrepresented in low-skilled jobs (Bevelander and Irastorza Citation2014). The manufacturing sector has traditionally been a major employment avenue for migrants in Sweden. Therefore, the gradual delocalisation of low-skilled manufacturing jobs after the 1970s has had a particularly large impact for migrants: while a third of male refugees were employed within the manufacturing sector in the late 1990s, only 5% did so in 2015 (Ruist Citation2018, 46). Two economic sectors have largely compensated for the job losses due to deindustrialisation: healthcare and food service activities. In 2015, as much as 60% of newly arrived refugee women were employed in the healthcare sector, often as nurses and care assistants (Ibid: 47; Åslund, Forslund, and Liljeberg Citation2017).

Residential context and migrant integration

Theoretical background

In recent years, a wide range of American and European studies have been published on the significance of the residential context for an individual’s socioeconomic career path, in domains such as education, employment, income and health. A seminal work within the neighbourhood effects literature is the book The Truly Disadvantaged by William Julius Wilson (Citation1987), which advances the view that residence in high poverty and ethnic minority neighbourhoods has detrimental consequences. Several theoretical arguments on the negative association between residential segregation and socioeconomic outcomes can be put forward. One theoretical argument centres on the stigmatisation of deprived and immigrant-dense neighbourhoods. It suggests that employers may be reluctant to hire individuals residing in neighbourhoods with a negative reputation. In that sense, residential segregation leads to, or reinforces, labour market discrimination (Schierup and Ålund Citation2011; Molina Citation1997).

Other arguments focus on socialisation processes. The concentration of immigrants in ethnic and high poverty areas is hypothesised to produce unfavourable social networks, hampering employment opportunities (Massey and Fong Citation1990; South, Crowder, and Chavez Citation2005). Moreover, individuals in deprived neighbourhoods tend to be excluded from other, more favourable social networks involving the native population. Such contacts could offer useful support for entering into and progressing in the labour market (Portes Citation1998). In line with this argument, some theorists suggest that residing in rural areas may facilitate immigrants’ integration because smaller societies provide more opportunities for interacting with the native population (Waters and Jiménez Citation2005; Hugo and Morén-Alegret Citation2008). In contrast, others highlight the positive role of co-ethnic residential concentration for integration. From that perspective, the ethnic social networks and ties existing within ethnic neighbourhoods can constitute a source of information, labour and capital for the members of that ethnic community (Musterd et al. Citation2008).

Finally, contextual effects are also discussed in the light of labour market characteristics. Regions affected by deindustrialisation and unemployment can constitute a hinderance to migrants’ labour market participation. In contrast, economically strong regions can act as ‘escalator regions,’ facilitating socioeconomic integration (Portes and Zhou Citation1993; Glick Schiller and Çaǧlar Citation2009; Van Ham et al. Citation2012). Large, internationally connected cities likely fall into the latter category. In The Global City, Saskia Sassen (Citation1991) suggests that cities such as London, New York and Tokyo, have witnessed the ‘tertiarisation’ of their economies, characterised by a surge of both top- and bottom-end service jobs. Those cities depend on the availability of low-paid/low-skilled migrant workers to service highly educated and highly paid employees, in sectors such as catering and cleaning.

In the light of these theoretical arguments, we derive the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Refugees residing in Stockholm are more likely to find a first employment (due to the city’s strong service-oriented economy and global competitiveness).

Hypothesis 2: Refugees residing in rural regions are more likely to find a first employment (due to better opportunities for socialisation with natives).

Hypothesis 3: Refugees residing in regions with high unemployment are less likely to find a first employment.

Hypothesis 4a: Refugees residing in neighbourhoods with a high concentration of non-Western migrants are less likely to find a first employment (due to stigmatisation and ‘negative socialisation’ processes).

Hypothesis 4b: Refugees residing in immigrant-dense neighbourhoods are more likely to find a first employment (due to the benefits of immigrant concentration).

Empirical evidence in Sweden

In the case of Sweden, the neighbourhood effects literature provides rather mixed results. Some studies find that residence in immigrant-dense and deprived neighbourhoods negatively affects immigrants’ employment and income situation (Musterd et al. Citation2008; Hedberg and Tammaru Citation2013; Wimark, Haandrikman and Nielsen Citation2019) as well as their education level (Grönqvist Citation2006). Andersson, Musterd, and Galster (Citation2018) found that initial settlement in a neighbourhood with a high proportion of co-ethnics had a negative effect on employment for refugee women, but not for men. Other studies highlight positive effects of immigrant concentration. Edin, Fredriksson, and Åslund (Citation2003) found that living in neighbourhoods with a high concentration of members of one’s ethnic group improved labour market outcomes for low-skilled refugees. Andersson and Hammarstedt (Citation2015) also found that ethnic enclaves enhanced self-employment propensities of Middle Eastern migrants in Sweden.

Regarding the role of the regional context for refugees’ socioeconomic outcomes, there are a number of studies examining the Swedish case. Research on refugees subject to the 1985–1994 refugee settlement policy—the ‘Sweden-wide strategy’Footnote1—generally suggests that dispersal had a detrimental effect on integration. Most refugees were indeed placed in small municipalities that had a housing surplus but limited work opportunities. Åslund and Rooth (Citation2007, 440) claimed that residence in high unemployment areas upon refugees’ arrival had negative effects on their earnings and employment for at least ten years after immigration. Other studies found similar results (e.g. Åslund, Östh, and Zenou Citation2010; Edin, Fredriksson, and Åslund Citation2004).

Research on more recently arrived refugee cohorts gives a complex picture. A number of studies showed that refugees residing in Stockholm had relatively higher odds of being employed while those in Malmö had the lowest odds (Bevelander and Lundh Citation2007; Bevelander Citation2011; Ruist Citation2018; Hedberg and Tammaru Citation2013Footnote2). Digging deeper into the characteristics of local labour markets, Bevelander and Lundh (Citation2007) also found that refugees had higher employment prospects in municipalities with a larger presence of manufacturing and private service jobs, as well as in municipalities with a lower average of education and skills level.

When it comes to population density, Statistics Sweden (Citation2016) found that refugees from the 2006–10 cohortFootnote3 had a higher probability of being gainfully employed five years after immigration if they had remained either in a metropolitan region or a region without a major city. Andersson (Citation2016) examined employment prospects among refugees from Iran, Iraq and Somalia who arrived between 1995 and 2004. The study analysed how initial settlement in different Swedish regions relates to the odds of being gainfully employed five years after arrival. Interestingly, Andersson found that regions associated with a greater likelihood of employment for refugees vary in terms of their population density and geographical location.

Our article brings a number of contributions to the existing scientific literature. On the one hand, our use of the region as the main unit of analysis is more suitable for the study of labour market dynamics. The combination of the regional context and the unique individual-centred neighbourhood variable allows us to simultaneously study the interplay between two scales of geographical context and labour market outcomes. Doing so for the whole population of refugees who arrived in Sweden in the 2000s over an extended period is another contribution of this study. Lastly, the event-history framework provides an appropriate methodological tool that makes full use of the time-varying longitudinal character of our dataset.

Data and methods

Study population

This paper is based on a compilation of Swedish administrative registers managed by Statistics Sweden, which contain longitudinal, annually updated and individual level data. The data include a wide range of variables, such as demographic, socioeconomic and residential characteristics.Footnote4

Our dataset consisted of refugees who immigrated to Sweden between 2000 and 2009 and were between 18 and 59 years old when they arrived in the country (N = 61,699). Individuals were followed over a nine-year period. We distinguished between three categories of refugees: refugees with assigned housing, refugees with self-arranged housing, and quota refugees. Since 1995, asylum seekers who are granted a residence permit can either be assigned to a municipality by the Swedish authorities (‘Kommunanvisad’) or arrange for their own housing (‘Egenbosatt’). To be entitled to assistance with their settlement into a municipality, the refugees must have previously resided in an accommodation provided by the Swedish Migration Agency during their asylum procedure (‘Anläggningsboende’ - ABO).Footnote5 Refugees who arrange for their own housing (‘Egenbosatt’) usually settle in metropolitan regions, while those with assigned housing tend to be placed in smaller municipalities (Statistics Sweden Citation2016, 48, 67). The third group of refugees—quota refugees—were resettled from refugee camps and did not arrive to Sweden by their own means. Therefore, they did not apply for asylum at the Swedish Migration Agency, but rather were directly assigned to a municipality. The distinction between these three categories is relevant to our study of the relationship between residential context and refugees’ employment. As refugees who are assigned housing have limited influence in the selection of the municipality where they settle, they are, in principle, less likely to be self-selected, compared to refugees with self-arranged housing, regarding the effect of the residential context on employment.Footnote6 There are also reasons to believe that these two categories of refugees have unobserved differential characteristics that are relevant to labour market inclusion. Indeed, the ability to arrange for their own housing suggests that this group may have higher levels of economic capital and social contacts, valuable assets in the job-seeking process. This claim was confirmed by empirical evidence (National Board of Housing, Building and Planning Citation2015, 87–88). Finally, previous research has also shown that quota refugees have worse employment prospects compared to other refugees (Bevelander Citation2011; Ruist Citation2018).

presents the characteristics of the study population, measured at the year of arrival in Sweden. Nearly two thirds of the refugees arrived during the second half of the 2000s. Half of the refugees (53%) arranged for their own accommodation, a third (35%) were assigned housing by the authorities, and 12% were quota refugees. The main regions of origin are the Middle East and North Africa, with as much as 75% of men and 63% of women originating from these regions. Iraq is by far the most common country of origin among refugees who arrived in Sweden during the 2000s. Former Yugoslavians make up the second largest group for the 2000–04 cohort, followed by Afghanis. Regarding the cohort that arrived in the second half on the decade, Somalis are the second largest group, followed by refugees from Central Asia. Around 43% of refugees in the study initially settled in a metropolitan region (Stockholm, Gothenburg or Malmö) and about a third settled in a large city region. Among metropolitan regions, Stockholm is the most common region of first settlement, hosting 24% of all refugees upon arrival.

Table 1. Characteristics of refugee population (between 18 and 59 years-old), measured at year of arrival in Sweden.

Analytical strategy

In this study, we applied discrete-time event history analysis to model refugees’ event of finding a first employment in Sweden. First, we created survival functions to describe the occurrence and timing of this event for different refugee groups. Second, we estimated discrete-time event history models based on a person-year dataset to explore the effect of residential context on the likelihood of finding a first employment. We estimated separate models for men and women, as is commonly done. As outlined above, we also differentiated between three categories of refugees—those with self-arranged housing, those with assigned housing, and quota refugees—for six models in total. The effects of the independent variables are reported as average marginal effects. In this way, we circumvent the problem of comparing odds ratios across different groups. See Mood (Citation2010) for a discussion in the context of logistic regression.

In Swedish administrative registers, individuals’ employment situation is registered every year in November. A person was considered at risk of becoming employed in a given year if she had never been employed or owned a business in November the preceding year. Thus, refugees entered the risk set the year following their immigration year. Individuals were right-censored (i.e. taken out of the risk set) if they had not found an employment by the end of the nine-year follow-up period, or if they emigrated or died at some point during the follow-up period.

An advantage of discrete-time models is that they allow for time-varying covariates (Allison Citation2010). In our analysis, the main independent variables were the time-varying variables on the regional and neighbourhood contexts. The models include two variables of the regional context: Type of region (based on population density and economic structure) and Regional unemployment. Regions correspond to local Labour Market Areas (LMAs), which are annually constructed by Statistics Sweden based on commuting zones. We used a single LMA classification per refugee cohort: the 2008 classification for the 2000–04 cohort and the 2013 classification for the 2005–09 cohort.Footnote7 The variable Type of region consists of five categories that describe the level of population density and the economic structure: 1. Stockholm; 2. Gothenburg; 3. Malmö; 4. large city regions; and 5. regions lacking a large city (hereafter ‘small city/rural regions’). This grouping was based on the 2017 classification of municipalities by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SKL). We chose to consider Sweden’s three metropolitan regions separately due to their different economic situations and political roles. Indeed, while Stockholm is Sweden’s administrative and financial centre, Gothenburg and especially Malmö have been coping with deindustrialisation processes. The time-varying variable High regional unemployment was measured by the region-level average of annual municipal unemployment rates. Regions above the third quartile of the distribution were considered to have high unemployment.

In addition to the regional context variables, a neighbourhood context variable controlled for the proportion of non-Western migrants among the person’s 500 closest neighbours.Footnote8 This variable was constructed as an individual-centred neighbourhood and calculated with the software EquiPop. Individual-centred neighbourhoods bypass the so-called ‘Modifiable Areal Unit Problem,’ a source of statistical bias affecting any geographical analysis based on arbitrarily defined aggregations of geographical areas (Östh, Malmberg, and Andersson Citation2014).

The model also controlled for other variables. The time-constant variables were Arrival cohort, Region of birth and Age at immigration. The remaining variables were time-varying. The variable Years in Sweden accounted for the number of years since immigration. We also controlled for individuals’ partnership statusFootnote9, their level of education, and whether they had children living in their household. The dummy variable Mobility status indicated whether the person still resided in the region of initial settlement. To ensure that changes in the time-varying independent variables had chronological precedence to the event of interest (finding a first employment), they were lagged, meaning that the risk of finding a first employment during a given year was modelled as dependent on the value of the independent variables the preceding year.

In addition to the independent and control variables, we constructed some additional contextual variables on the regional labour market context. In our dataset, these variables were highly correlated with Type of region (our main independent variable), leading to multicollinearity, and thus have been excluded from the regression models described in our results. Instead, we used these variables descriptively to deepen our understanding of the labour-market situation in different types of regions and to illuminate the interpretation of differentials in model coefficients across regional contexts. Occupational skill level classifies regions based on the average skill level of the individuals working in the region during a given year. We distinguished three skill categories, including: 1. blue-collar workers; 2. white-collar workers; and 3. managers. The average skill was then weighted by the number of individuals in each category. (See Bevelander and Lundh (Citation2007) for a similar classification.) We also constructed variables counting the relative size of three Economic sectors in the region, including: manufacturing and mining, private services, and the public sector. Finally, we calculated the relative size of the refugee population in the region among residents aged 16 and above.

Limitations

Some researchers have pointed out possible empirical gaps in the neighbourhood effects literature, chiefly the overlook of selective sorting into neighbourhoods/regions or the fact that mobility patterns vary across social and ethnic groups (Hedman and van Ham Citation2011). For instance, people settling in deprived neighbourhoods tend to have a lower socioeconomic background than those settling in more affluent neighbourhoods and are more likely to be foreign-born (Andersson and Bråmå Citation2004). Additionally, migrants who are most motivated to advance in employment careers may choose to settle in the regions providing the most advantageous opportunities (Åslund Citation2005). These selection mechanisms are not independent of the employment outcome under study. Thus, selection bias is an issue we should be aware of and address. From a modelling standpoint, estimating the likelihood of getting the first employment at a single time point increases selection issues. We attempted to mitigate this by taking time into account, using event history analysis to estimate the probability of obtaining a first employment based on time-varying covariates, both at the individual and at the contextual level. This, however, does not eliminate the possibility of a sorting into regions and neighbourhoods occurring upon first settlement.Footnote10

Results

Timing to first employment

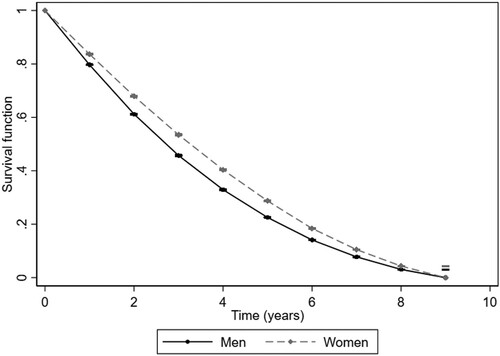

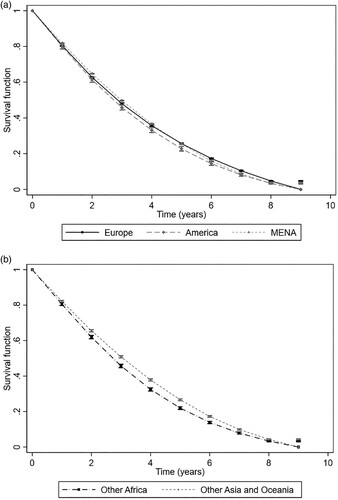

In a first step, we plotted Kaplan-Meier survival function curves to describe the timing to the event of refugees’ getting their first employment, grouped by gender and birth region. The survival functions in and show the proportion of refugees that have not entered the labour market, by years of residence in Sweden. It is important to note that the survival functions describe the proportion of refugees who have not found a first job by a certain point in time, and not the proportion who are not employed at that point in time. An initial observation is that refugee women take a longer time to enter the labour market than refugee men. For instance, it takes around five years for women to reach a first employment rate of 70%, whereas men reach that proportion after only four years. Part of this difference is likely due to women spending longer periods on parental leave. Beside gender differences, shows clear differences in the rate and timing of obtaining a first employment by birth region. The timing of transition into first employment is shorter for refugees from America and Other Africa. In contrast, refugees from the Middle East and North Africa and from the rest of Asia and Oceania enter the labour market more slowly. However, the differences between regions of origin are rather small and the confidence intervals are partly overlapping. We will later see whether these differences remain in the regression analysis.

Geographical distribution of the refugee population

Given that the present study focuses on the relationship between geographical context and entry into employment, it is important to examine the distribution of the refugee population across geographical contexts. summarises the distribution of the three refugee categories—those with self-arranged housing, those with assigned housing and quota refugees—by type of region and mobility status (averaged over the observation period). As mentioned above, refugees with assigned housing are often placed in small localities while refugees who arrange for their own housing tend to settle in metropolitan regions. Accordingly, 64% of the refugees with self-arranged housing in our study resided in a metropolitan region at some point in time, while this is only the case for 19% of those with assigned housing and quota refugees. The latter categories are overrepresented in large cities and rural regions. They also stand out by their higher levels of inter-regional mobility. Indeed, a quarter of refugees with assigned housing have moved across regions during the follow-up period. This is only the case for 8% of the refugees with self-arranged housing. These patterns can imply that, for assigned refugees, relocation constitutes a readjustment to satisfying their preferences in terms of region. Finally, refugees who arranged for their own housing also have a higher proportion of non-Western neighbours. This is consistent with the fact that they more often reside in metropolitan regions, which include neighbourhoods with a high immigrant concentration.

Table 2. Distribution of refugee categories by type of region and mobility status (average over observation period).

Residential context and first employment

The results of the discrete-time event history models are displayed in . We report average marginal effects and their standard errors.

Table 3. Part 1. Results from discrete-time survival models on entry into first employment among refugees, 2001–15 (average marginal effects in percentage points).

Table 3. Part 2. Results from discrete-time survival models on entry into first employment among refugees, 2001–15 (average marginal effects in percentage points).

A first important observation relates to the clear differences in the probabilities of finding a first employment between types of regions. For all categories of refugees, Stockholm is associated with the highest probability of finding a job and Malmö with the lowest. For example, controlling for everything else, male refugees with self-arranged housing in Malmö have on average a 7.5% lower probability than their counterparts in Stockholm. The type of region associated with the second highest likelihood of finding a first job among men are small city/rural areas. This is also the case for women who arranged for their own housing.

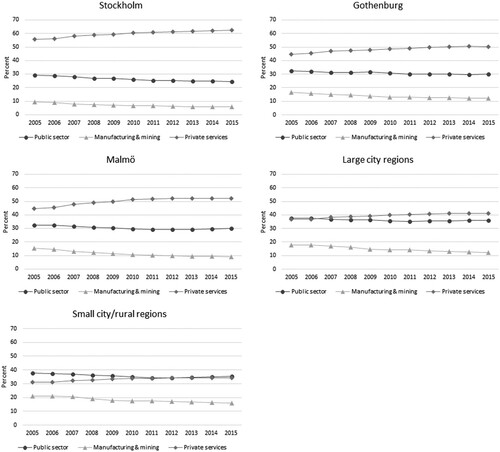

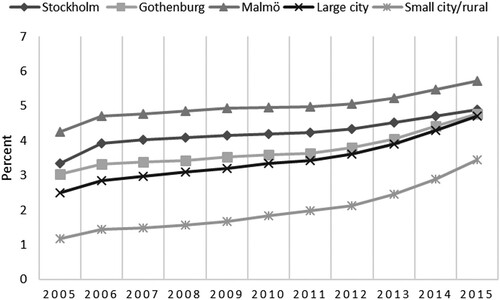

The finding that Stockholm is associated with the highest employment prospects for refugees is consistent with previous research (e.g. Bevelander Citation2011; Andersson Citation2016; Ruist Citation2018) and supports Hypothesis 1. The positive effect of small city/rural regions confirms Hypothesis 2, which assumes better opportunities for socialisation with natives in those regions. However, in order to better interpret differences in employment probabilities between regions, it is useful to examine a number of labour market-related characteristics of the five region types: the predominance of different economic sectors (manufacturing and mining, private services, and the public sector), the average occupational skill level and the relative size of the refugee population. As mentioned in the Data and Methods section, these variables were not included in the models because they are highly correlated with the variable Type of region.Footnote11 depicts the relative size of three main economic sectors by type of region over the period of 2005–15. Stockholm has by far the largest proportion of private services jobs and the smallest proportion of manufacturing jobs.

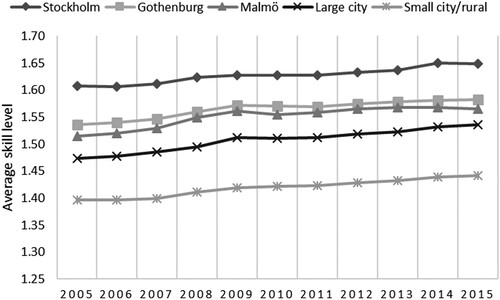

This is an indication of the region’s service-oriented, post-industrial economy and its global competitiveness, as theorised by Sassen (Citation1991). The large size of the private service sector in Stockholm is certainly an important factor behind the region’s higher employment opportunities. Indeed, the private service sector includes jobs requiring low qualifications, such as cleaning and food services, which are typical entry-level jobs for immigrants in Sweden (Åslund, Forslund, and Liljeberg Citation2017). The private service sector has a similar relative size in Gothenburg and Malmö, but the manufacturing sector has declined more sharply in Malmö since 2005. Given that industry has historically been a major sector of employment for migrants in Sweden, its sharp decline in Malmö may be a factor behind their poor labour market performance in that region. Likewise, the fact that the relative size of the manufacturing sector is largest in small city/rural regions could partly explain refugees’ relatively better employment prospects in those regions, especially for men. illustrates the average skill level of the working population by type of region during the period of 2005–15.Footnote12 It clearly shows that a region’s average occupational skill level increases with its population density. As migrants tend to be overrepresented in low-skilled occupations (Bevelander and Irastorza Citation2014), the lower skill level in rural areas may be a reason why these regions are positively associated with employment.

The poor labour market outcomes in Malmö are likely related to general economic developments in the region. In conjunction with its deindustrialisation, Malmö has suffered from high unemployment and a growing social polarisation (Holgersen and Baeten Citation2017). The proportion of individuals living in relative poverty amounted to 21% in Skåne County in 2010 compared to 13% in Stockholm County (Niedomysl, Östh, and Amcoff Citation2015, 24). Finally, high refugee concentration can also be part of the explanation. Indeed, as shown in , Malmö consistently has the highest proportion of refugees in its population. A plausible assumption is that a large refugee population is associated with increased competition for the same job types, restraining employment possibilities. It may, therefore, be more difficult for refugees to find employment in Malmö due to higher competition for low-skilled jobs among refugees and other immigrants (Ruist Citation2018, 56).

The results of the dummy variable on high regional unemployment were not statistically significant in five out of the six models. The exception was women with assigned housing for whom high unemployment regions are surprisingly associated with a higher probability of finding employment. Thus, we did not find evidence for Hypothesis 3, which assumes that residence in high unemployment regions decreases the chances of becoming employed. It is worth noting that our models control for the Type of region.Footnote13 The effect of regional unemployment is therefore partially captured by the Type of region variable, so the unemployment variable measures the effect of regional unemployment on top of the population density effect and economic structure; it is this effect that turns out not to be statistically significant. The positive effect of high unemployment regions for female refugees with assigned housing is unexpected. Maybe these women find employment in sectors that suffer from labour force shortage even within high unemployment regions. Healthcare could be such a sector, as its demand is spread all over the country, irrespective of the economic conjuncture.

The neighbourhood-level variable in our models assesses the effect of proximity to non-Western migrants on refugees’ employment likelihood. With the exception of male quota refugees, we find statistically significant negative effects of residential proximity to non-Western migrants. For men with self-arranged housing, controlling for everything else, a marginal increase in the proportion of non-Western migrants among the 500 nearest neighbours implies a 4% lower probability of becoming employed. The results support Hypothesis 4a on the negative consequences of immigrant concentration and contradict Hypothesis 4b on its positive effects.

With selection considerations in mind, it can be argued that Stockholm has the highest employment probability because it attracts refugees with more motivation to work and who have higher skills. Similarly, those who decide to settle in Malmö may do so for social reasons—to be close to family and friends—rather than employment reasons (Ruist Citation2018). As a result, Malmö may be the most obvious destination for refugees with lower qualifications and lower job-seeking capacities.

Selection considerations are also important for the interpretation of Mobility status (whether the person has left her first region of settlement in Sweden). We find that inter-regional mobility has a statistically significant and negative effect on the employment prospects for two groups of refugees: men with self-arranged housing and women with assigned housing. A plausible interpretation is that these two categories of refugees would undergo inter-regional mobility for different reasons. Men with self-arranged housing may have taken into consideration employment prospects in the selection of municipality of first settlement. It is also likely that their choice was motivated by the presence of family or friends already established in the municipality. These social connections can constitute valuable resources in the job-seeking process through the sharing of knowledge about job opportunities and the local labour market. Members of this group who left their initial region of residence would have to ‘start from scratch’ in their region of destination. For female refugees with assigned housing, a reasonable assumption is that relocation is motivated by social rather than by employment considerations.Footnote14

Overall, the patterns of the regional variables are essentially similar for the different refugee categories: Stockholm is consistently the most advantageous region, followed by small city/rural regions, while Malmö is the least advantageous. However, we also found that the effect of certain regions was less negative for the most atypical refugee groups in those regions. Indeed, refugees with assigned housing in Gothenburg, and especially females, have a higher probability of finding a first job compared to the most dominant group of refugees with self-arranged housing. Similarly, residence in a small city/rural region is more positively associated with employment for refugees with self-arranged housing, who are the least common group. A possible interpretation is that refugees who actively choose to settle outside a large city possess social or cultural resources facilitating their labour market integration. It may also be the case that refugees with self-arranged housing in Gothenburg settle in that region for reasons that are not labour market related.

Lastly, our models also controlled for several sociodemographic variables known to influence migrants’ transition into employment. We found that refugees’ chances of getting a job increase with their level of education. Moreover, the older the person is upon arrival in Sweden, the lower their probability of finding a job. Single individuals are also less likely to become employed, while the effect of being a parent differs between refugee groups. As in previous research, motherhood decreases employment probability for female refugees with self-arranged housing. The effect of fatherhood, surprisingly, differs between categories of male refugees: it has a positive effect for those with assigned housing and a negative effect for quota refugees (although only significant at the 5% level). The most recent refugee cohort (2005–09) has consistently higher probabilities of obtaining a first employment than the earlier cohort (2000–04). Our analysis also showed considerable differences by region of birth. Refugees from the Middle East and North Africa have a lower probability of finding a first job than refugees from Europe. The differences in the probabilities between refugee groups even after controlling for differences in sociodemographic and contextual characteristics suggest the presence of labour market discrimination against certain ethnic groups.Footnote15 Finally, as expected, the probabilities increase over the amount of time spent in Sweden.Footnote16

Conclusions

In this study, we explored the interplay between refugees’ regional and neighbourhood context and their employment situation using discrete-time event history analysis. A central finding from our analyses is that Stockholm is the most advantageous region in terms of labour market prospects, while Malmö is the least advantageous. This is consistent with previous research (e.g. Bevelander Citation2011; Andersson Citation2016; Ruist Citation2018). Based on a closer look at the labour market evolution over the last decades, we argue that the different economic developments in the two metropolitan regions have a strong impact on refugees’ labour market outcomes. While Stockholm has experienced economic growth since the 1990s, Malmö has suffered from rising unemployment in conjunction with deindustrialisation (Holgersen and Baeten Citation2017). Stockholm can be considered a post-industrial ‘global city’ that offers employment opportunities for low-skilled migrants working in the service sector (Sassen Citation1991). On the other hand, Malmö has been less successful in restructuring to a post-industrial economy. Moreover, Malmö has a large refugee population, partly due to its location as a point of entry for refugees coming by land, leading to chain migration. Poorer economic prospects and increased competition for low-skilled jobs are likely factors behind the worse employment outcomes for refugees in the region.

Another important result is that small city/rural regions are the second most advantageous regions when it comes to finding employment for most refugees. As some theorists suggest (Waters and Jiménez Citation2005; Hugo and Morén-Alegret Citation2008), this could be explained by accrued opportunities for socialisation with native-born residents in those regions, which can be beneficial to refugees in their job-seeking process. Labour market advantages for refugees in rural areas were highlighted by Statistics Sweden (Citation2016) in the case of refugees from the 1990–94 and the 2006–10 cohort. A qualitative study by the National Board of Housing, Building and Planning (Citation2015) also stressed the positive effects of rural living for social inclusion. It concluded that refugees who settled in rural municipalities on their own initiative had higher possibilities for social interaction with the majority population, not least in schools. To sum up, our results show a complex pattern where the two types of regions with the highest probability of finding a first employment are those at the extremes of the population density distribution.

Finally, our study shows that a higher proximity to non-Western migrants decreases the probability of obtaining a first employment. This result gives support to arguments pointing at processes of ‘negative socialisation’ and stigmatisation at play in immigrant-dense neighbourhoods. It should be pointed out that our analysis differs from previous neighbourhood effects studies about refugee (or migrant) employment in Sweden. First, while many studies solely analysed the effect of migrants’ residential context upon arrival in Sweden (sometimes called ‘port of entry’) (e.g. Edin, Fredriksson, and Åslund Citation2004; Åslund and Rooth Citation2007; Åslund, Östh, and Zenou Citation2010; Andersson, Musterd, and Galster Citation2018; Wimark, Haandrikman, and Nielsen Citation2019), the use of event history analysis allowed us to follow refugees’ residential context over a longer period, incorporating changes in residential context in our analyses. A second innovative aspect is that we used individual-centred neighbourhoods instead of predefined administrative areas to investigate contextual effects on employment. Yet, the previous Swedish studies employing that method (e.g. Musterd et al. Citation2008; Wimark, Haandrikman, and Nielsen Citation2019) focused on the broader immigrant population and not specifically on refugees. Third, we measured neighbourhood context based on the proportion of non-Western neighbours. Other studies have analysed other neighbourhood characteristics, such as level of deprivation (e.g. Wimark, Haandrikman and Nielsen Citation2019) or proportion of co-nationals, e.g. (Andersson, Musterd, and Galster Citation2018). The latter interestingly found negative effects of proximity to co-nationals on employment for women but not for men.

Our results hint at possible policy implications. A government-appointed committee recently proposed the re-introduction of restrictions to the freedom of asylum seekers to arrange for their own accommodation in municipalities with socio-economically disadvantaged neighbourhoods (SOU Citation2018, 41). This policy proposal seeks to prevent social exclusion and overcrowding among refugees and achieve a more even distribution of refugee reception across municipalities. Based on our analyses, we believe this policy can reduce the concentration of asylum seekers in ethnically and socioeconomically segregated neighbourhoods. However, it is essential that refugee settlement policy also takes into consideration refugees’ labour market prospects. Based on our results, the possibility for new refugees to settle in certain disadvantaged neighbourhoods in Malmö should indeed be the subject of a closer examination. On the other hand, preventing asylum seekers from settling in Stockholm may undermine their labour market incorporation. In addition, the positive association between rural regions and employment (controlling for high regional unemployment) suggests that settlement in smaller, but strong labour markets could be beneficial for refugees’ integration. Finally, the poor labour market prospects of refugees in Malmö call for particular policy attention in this region.

One point for further research concerns alternative measures of residential context and labour market integration. At the neighbourhood level, one could analyse the proportion of co-nationals among an individual’s closest neighbours and even the proportion of co-nationals with certain education and employment characteristics (as in Andersson, Musterd, and Galster’s (Citation2018) work). Given the prominence of socialisation-related arguments in the literature on contextual effects, one could also classify neighbourhoods and regions based on their level of social capital. An example using Swedish municipalities can be found in a recent study by Östh et al. (Citation2018). In addition to the transition into first employment, it may be worth investigating other socioeconomic outcomes such as employment stability, type of occupation, sector of employment, and disposable income. These avenues of further research are not restricted to the individual level but can lead to better measures of integration for the regions themselves, allowing for the identification of best practices and synergies. Moreover, it would be interesting to study the relationship between the regional context and employment for other refugee cohorts (such as those who were subject to a compulsory placement as part of the ‘Sweden-wide strategy’ between 1985 and 1994) and other international migrants more generally. Finally, while quantitative studies are necessary for the understanding of statistical patterns and determinants of refugees’ labour market participation, additional interview- and survey-based research is needed to get a deeper understanding of refugees’ job-seeking process.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful for the valuable feedback received at various seminars and conferences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The ‘Sweden-wide strategy’, which was implemented between 1985 and 1994, limited the freedom of newly arrived asylum seekers to settle where they wanted. The main objective of the reform was to offset the concentration of new refugees in metropolitan regions (Åslund Citation2005).

2 This study looked at all immigrants, not just refugees.

3 This applies to refugees who arranged their own housing once they were granted residence permit (‘Egenbosatt’). See Data and Methods section.

4 Refugees appear in Swedish registers once they are granted a residence permit. This means that they may have resided in Sweden for a certain amount of time before getting a residence permit, and that period does not appear in the governmental records (Statistics Sweden Citation2016).

5 It is important to distinguish the housing arrangements of refugees (that is asylum seekers who have been granted residence permit) from those of asylum seekers during the asylum-seeking process. During the asylum-seeking process, asylum seekers have the choice between arranging for their own accommodation (‘Eget boende’, EBO) or being accommodated by the Swedish Migration Agency (‘Anläggningsboende’, ABO) (SFS Citation1994).

6 It is the Swedish Migration Agency that performs the matching between refugees seeking assistance with their settlement and municipalities. From 2007, the Swedish Migration Agency has been taking into consideration labour market proximity as an allocation criterion. Getting a job or a job offer could also constitute a special reason to be allocated to a specific municipality (Swedish Migration Agency Citation2007). Despite these considerations, refugees with assigned housing have had at most a limited influence on the decision on their municipality of settlement.

7 We used a single LMA classification per refugee cohort in order to be able to control for the effect of inter-regional mobility on the probability of finding a first employment. This also ensures that changes in the level of population density and regional unemployment are not due to changes in LMA borders.

8 In this study, we chose to examine the proximity of non-Western migrants due to their larger cultural distance from natives, which allows us to test Hypothesis 4a regarding the stigmatisation of immigrant-dense neighbourhoods. Inspired by the socialisation arguments, we opted for the 500 closest neighbours because it roughly corresponds to the number of neighbours one may recognise and communicate with.

9 The category ‘Having a partner’ includes married couples, registered partners, and cohabitants with common children.

10 Another selection aspect concerns unobserved heterogeneity of individuals, which may give rise to individual-based selection in the transition to first employment. This means, for instance, that some time-constant individual traits that are not directly measured could make some refugees more likely to seek new job opportunities, or conversely, more likely to conform to what they have. An alternative modelling strategy to address this particular self-selection issue would be the use of fixed effects models, which focus on controlling for unobserved variation among individuals. In our case, however, it turns out that around 84% of individuals in the study population do not change type of region during the whole observation period. This implies that the within-type variance is very low, which is a problem in fixed effects models (Petersen Citation2009, 338–339). Running fixed effects models on the fraction of the study population that exhibits variation in the region type would have resulted in a loss of information, so we opted for event history analysis.

11 Spearman’s correlation between Type of region and the ratio of manufacturing and mining jobs was rs = 0.755 (for the entire dataset). The corresponding correlation with the ratio of private services was rs = -0.910 and with public sector jobs rs = 0.720.

12 The variable Type of region is highly correlated with the average skill level in the region: rs = -0.898.

13 We estimated models including an ordinal unemployment level variable and excluding Type of region, and we found statistically significant negative effects for residence in high unemployment regions. This ordinal variable could not be included in the models with the Type of region variable due to high correlation: rs = 0.650.

14 A recent report by Statistics Sweden (Citation2016) similarly found that refugees with self-arranged housing who stayed either in a metropolitan region or in a region without a large city had a higher probability of being employed five years after arrival.

15 Studies showing evidence of ethnic discrimination in the Swedish labour market include the articles by Rydgren (Citation2004) and by Arai, Bursell, and Nekby (Citation2016).

16 Several robustness checks were performed. First, we ran the models including a Year variable to account for potential period effects in employment. However, we did not keep the variable in the final models due to high correlation with the variables Years in Sweden (r=0.597) and Refugee cohort (rs = 0.664). This did not affect the results. Second, we controlled for the ratio of refugees in the region, but the coefficients of this variable were not statistically significant. Finally, we estimated models by gender where the refugee category was an independent variable. This did not change the results of the variables Type of region and Proximity to non-Western migrants.

References

- Allison, P. D. 2010. “Survival Analysis.” In The Reviewer's Guide to Quantitative Methods in the Social Sciences, edited by G. R. Hancock, and R. O. Mueller, 413–425. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Andersson, R. 2016. “Flyktingmottagandets geografi – en flernivåanalys av integrationsutfallet för tio årskohort av invandrare från Somalia, Irak och Iran.” [The Geography of Refugee Reception – a Multilevel Analysis of Integration for ten-year Cohort of Immigrants from Somalia, Iraq and Iran] In Mångfaldens Dilemman [The Dilemma of Multiculturalism], edited by R. Andersson, B. Bengtsson, and G. Myrberg, 39–73. Malmö: Gleerups.

- Andersson, R., and Å Bråmå. 2004. “Selective Migration in Swedish Distressed Neighbourhoods: Can Area-Based Urban Policies Counteract Segregation Processes?” Housing Studies 19 (4): 517–539. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0267303042000221945

- Andersson, L., and M. Hammarstedt. 2015. “Ethnic Enclaves, Networks and Self-Employment among Middle Eastern Immigrants in Sweden.” International Migration 53 (6): 27–40. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2011.00714.x

- Andersson, R., S. Musterd, and G. Galster. 2018. “Port-of-Entry Neighbourhood and its Effects on the Economic Success of Refugees in Sweden.” International Migration Review. Published online. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0197918318781785.

- Arai, M., M. Bursell, and L. Nekby. 2016. “The Reverse Gender Gap in Ethnic Discrimination: Employer Stereotypes of Men and Women with Arabic Names.” International Migration Review 50 (2): 385–412. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12170

- Åslund, O. 2005. “Now and Forever? Initial and Subsequent Location Choices of Immigrants.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 35 (2): 141–165. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2004.02.001

- Åslund, O., A. Forslund, and L. Liljeberg. 2017. “Labour Market Entry of Non-Labour Migrants–Swedish evidence”. Working Paper Series 2017:15, IFAU - Institute for Evaluation of Labour Market and Education Policy.

- Åslund, O., J. Östh, and Y. Zenou. 2010. “How Important is Access to Jobs? Old Question-Improved Answer.” Journal of Economic Geography 10 (3): 389–422. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbp040

- Åslund, O., and D. O. Rooth. 2007. “Do When and Where Matter? Initial Labour Market Conditions and Immigrant Earnings.” The Economic Journal 117 (518): 422–448. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2007.02024.x

- Bevelander, P. 2011. “The Employment Integration of Resettled Refugees, Asylum Claimants, and Family Reunion Migrants in Sweden.” Refugee Survey Quarterly 30 (1): 22–43. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/rsq/hdq041

- Bevelander, P., and N. Irastorza. 2014. “Catching up: The Labour Market Integration of New Immigrants in Sweden”. Migration Policy Institute and International Labour Organization, 28.

- Bevelander, P., and C. Lundh. 2007. “Employment Integration of Refugees: The Influence of Local Factors on Refugee Job Opportunities in Sweden”. Discussion Paper; 2551, 43, IZA, University of Bonn.

- Edin, P.-A., P. Fredriksson, and O. Åslund. 2003. “Ethnic Enclaves and the Economic Success of Immigrants - Evidence From a Natural Experiment.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 118 (1): 329–357. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/00335530360535225

- Edin, P.-A., P. Fredriksson, and O. Åslund. 2004. “Settlement Policies and the Economic Success of Immigrants.” Journal of Population Economics 17 (1): 133–155. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-003-0143-4

- Glick Schiller, N., and A. Çaǧlar. 2009. “Towards a Comparative Theory of Locality in Migration Studies: Migrant Incorporation and City Scale.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35 (2): 177–202. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830802586179

- Grönqvist, H. 2006. “Ethnic Enclaves and the Attainments of Immigrant Children.” European Sociological Review 22 (4): 369–382. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcl002

- Hedberg, C., and T. Tammaru. 2013. “‘Neighbourhood Effects’ and ‘City Effects’: The Entry of Newly Arrived Immigrants Into the Labour Market.” Urban Studies 50 (6): 1165–1182. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098012461674

- Hedman, L., and M. van Ham. 2011. ““Understanding Neighbourhood Effects: Selection Bias and Residential Mobility”.” In Neighbourhood Effects Research: New Perspectives, edited by M. van Ham, D. Manley, N. Bailey, L. Simpson, and D. Maclennan, 79–100. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Holgersen, S., and G. Baeten. 2017. “Beyond a Liberal Critique of ‘Trickle-Down': Urban Planning in the City of Malmö.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 40 (6): 1170–1185. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12446

- Hugo, G., and R. Morén-Alegret. 2008. “International Migration to Non-Metropolitan Areas of High Income Countries: Editorial Introduction.” Population Space Place 14 (6): 473–477. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.515

- Irastorza, N., and P. Bevelander. 2017. “The Labour Market Participation of Humanitarian Migrants in Sweden: An Overview.” Intereconomics 52: 270–277. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10272-017-0689-0

- Massey, D. S., and E. Fong. 1990. “Segregation and Neighbourhood Quality: Blacks, Hispanic and Asians in the San Francisco Metropolitan Area.” Social Forces 69 (1): 15–32. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/2579605

- Molina, I. 1997. Stadens racifiering. Etnisk boendesegregation i folkhemmet [Racialisation of the city. Ethnic Residential Segregation in the Swedish Population]. Geografiska Regionstudier 32, Uppsala University, Department of Social and Economic Geography.

- Mood, C. 2010. “Logistic Regression: Why we Cannot do What we Think we can do, and What we can do About it.” European Sociological Review 26 (1): 67–82. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcp006

- Musterd, S., R. Andersson, G. Galster, and T. M. Kauppinen. 2008. “Are Immigrants’ Earnings Influenced by the Characteristics of Their Neighbours?” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 40 (4): 785–805. doi: https://doi.org/10.1068/a39107

- National Board of Housing, Building and Planning [Boverket]. 2015. “Boendesituationen för Nyanlända Slutrapport” [Housing Situation for Newly Arrived]. Rapport 2015:40 Regeringsuppdrag. Karlskrona: Boverket.

- Niedomysl, T., J. Östh, and J. Amcoff. 2015. “Boendesegregationen i Skåne” [Residential Segregation in Skåne]. Kristianstad: Region Skåne.

- OECD. 2018a. “Foreign-born Employment”. Accessed 6 July 2018. https://data.oecd.org/migration/foreign-born-employment.htm#indicator-chart

- OECD. 2018b. “Native Employment”. Accessed 6 July 2018. https://data.oecd.org/migration/native-born-employment.htm#indicator-chart

- Östh, J., M. Dolciotti, A. Reggiani, and P. Nijkamp. 2018. “Social Capital, Resilience and Accessibility in Urban Systems: A Study on Sweden.” Networks and Spatial Economics 18 (2): 313–336. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11067-017-9375-9

- Östh, J., B. Malmberg, and E. Andersson. 2014. “Analysing Segregation with Individualized Neighbourhoods Defined by Population Size.” In Social-Spatial Segregation: Concepts, Processes and Outcomes, edited by C. D. Lloyd, I. Shuttleworth, and D. Wong, Ch. 7, 135–161. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Petersen, T. 2009. “Analyzing Panel Data: Fixed- and Random-Effects Models.” In The Handbook of Data Analysis, edited by M. Hardy and A. Bryman, 332–345. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Portes, A. 1998. “Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology.” Annual Review of Sociology 24: 1–24. doi: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.1

- Portes, A., and M. Zhou. 1993. “The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and Its Variants.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 530: 74–96. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716293530001006

- Ruist, J. 2018. “Tid för integration – en ESO-rapport om flyktingars bakgrund och arbetsmarknadsetablering.” [Time for integration - an ESO-report on refugees’ background and labour market participation]. Rapport till Expertgruppen för studier i offentlig ekonomi 2018: 3.

- Rydgren, J. 2004. “Mechanisms of Exclusion: Ethnic Discrimination in the Swedish Labour Market.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 30 (4): 697–716. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830410001699522

- Sassen, S. 1991. The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Schierup, C.-U., and A. Ålund. 2011. “The End of Swedish Exceptionalism? Citizenship, Neoliberalism and the Politics of Exclusion.” Race and Class 53 (3): 45–64. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0306396811406780

- SFS. 1994. “Lag om mottagande av asylsökande m.f.” [Law on the reception of asylum seekers et al.]. SFS 1994: 137.

- SOU 2018:22. 2018. Ett Ordnat Mottagande – Gemensamt Ansvar för Snabb Etablering eller Återvändande. [An Orderly Reception – Common Responsibility for Prompt Establishment or Return]. Stockholm: Norstedts Juridik.

- South, S. J., K. Crowder, and E. Chavez. 2005. “Geographical Mobility and Spatial Assimilation among U.S. Latino Immigrants.” International Migration Review 39 (3): 577–607. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2005.tb00281.x

- Statistics Sweden. 2016. “Integration – Flyktningars Flyttmönster i Sverige”. [Integration – Refugees’ Mobility Patterns in Sweden] Integration. Rapport 10. Örebro: Statistics Sweden.

- Swedish Migration Agency. 2007. “Årsredovisning 2007” [Annual report 2007]. Migrationsverket.

- Van Ham, M., A. Findlay, D. Manley, and P. Feijten. 2012. “Migration, Occupational Mobility and Regional Escalators in Scotland.” Urban Studies Research 2012: 1–15. doi: https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/827171

- Waters, M. C., and T. R. Jiménez. 2005. “Assessing Immigrant Assimilation: New Empirical and Theoretical Challenges.” Annual Review of Sociology 31 (1): 105–125. doi: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100026

- Wiesbrock, A. 2011. “The Integration of Immigrants in Sweden: a Model for the European Union?” International Migration 49: 48–66. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2010.00662.x

- Wilson, W. J. 1987. The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass and Public Policy. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Wimark, T., K. Haandrikman, and M. M. Nielsen. 2019. “Migrant Labour Market Integration: The Association Between Initial Settlement and Subsequent Employment and Income among Migrants.” Geografiska Annaler B: Human Geography. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.2019,1581987.