ABSTRACT

Extraterritorial migration management perspectives on how states try to enforce immigration controls beyond their juridical borders are strongly influenced by ‘remote control’ metaphors. This is conceptually limited and outdated. Most research fails to sufficiently acknowledge agency by a destination state's officials acting abroad, foreign states and their officials, when evaluating extraterritorial measures and ‘outcomes’. We study UK liaison officers abroad, specifically, how they see their efforts to implement extraterritorial immigration control through interactions with foreign state officials. Our approach links inter-state relations to the social world of on-the-ground ‘street-level’ interactions between officers abroad and their foreign counterparts. The empirical analysis draws from original interviews and official sources. We compare factors accounting for the UK's activities and perceived ‘outcomes’ across USA, France, Thailand, Egypt and Ghana. Findings show the UK's extraterritorial migration management results from a very long chain of decisions and actions, by foreign and UK state actors, operating at different institutional-levels, with uncontrollable local circumstances abroad. Realising extraterritorial goals depends strongly on liaison officers’ agency, ‘soft power’ over foreign officials and foreign officials’ willingness to cooperate. Meanwhile liaison officers’ ‘feedbacks’ importantly influence Home Office decision-making. Against the simplistic one-way causality of ‘remote control’, this is ‘street-level’ agency beyond ‘remote control’.

Introduction

Over the last decades, a significant literature has emerged on liberal nation-states’ strategies for extraterritorial migration management: immigration control operations that take place beyond a state's own juridical borders on foreign sovereign territory (Boswell Citation2003; Lavenex Citation2006; Ryan and Mitsilegas Citation2010; Zaiotti Citation2016). Following Zolberg's influential study, a state's efforts to impose extraterritorial controls are usually discussed through ‘remote control’ metaphors (Zolberg Citation1997:308; Citation2003). In an important update, FitzGerald offers a definition (Citation2020:9): ‘Remote control is a set of practices, physical structures, and institutions whose goal is (to) control the mobility of individuals while they are outside the territory of their intended destination state. One goal is to filter migrants and select whom can pass. Another goal is to identify, monitor, detain, deport, and deter the unwanted through an architecture of repulsion’. This research field strongly focuses on receiving states’ efforts to exert highly restrictive policies through actions abroad, especially preventing asylum seekers at source and in transit. In this way, liberal nation-states bypass ‘liberal’ obligations they place on themselves on their own sovereign territory for upholding human, civil and personhood rights, including non-refoulement (Joppke Citation1998).

While acknowledging important advances, we argue inherent limitations persist. ‘Remote control’ invokes the technology of an age when it appeared novel that people changed channels on their analogue television sets by pushing a button while remaining in the comfort of their armchairs. But the world is no longer analogue. Applying ‘remote control’ metaphors to immigration, keeps the idea that the only actor who matters and has agency is the destination liberal-state, that once desired, ‘remote control’ is relatively easily achieved, and ‘outcomes’ are determined by the button-pusher's preferences. All these assumptions are questionable, but ‘remote control’ remains an influential interpretive framework.

By arguing for a perspective on agency beyond ‘remote control’, we build on conceptual advances that emphasise the global interconnectedness of a nation-state system of extraterritorial migration controls (FitzGerald Citation2019, Citation2020), while providing original substantive evidence that the UK's approach is shaped by factors little discussed by most ‘remote control’ studies: how agency by liaison officers abroad, foreign states, and their officials, influences ‘outcomes’. To move beyond destination-state-centric ‘remote control’ perspectives, we study how the UK Home Office's efforts to enforce extraterritorial initiatives are strongly shaped by: first, relationships with foreign states, with their own policy priorities over population movement; second, UK officers’ attempts to establish meaningful relations abroad and influence their foreign counterparts; and third, foreign state immigration and law enforcement officers’ willingness to act in ways that support the UK's goals. We examine British liaison officers’ perceptions of their activities, working relations with foreign counterparts, effectiveness, ‘feedbacks’ to the Home Office, and resultant ‘outcomes’.

The UK's liaison network, Immigration Enforcement International (IEI)Footnote1, comprises civil servants posted abroad, who evaluate conditions, provide information, and help enforce the visa system and immigration goals, as a ‘main delivery agent for offshore migration control’ (FCO 2008:107). It is the ‘overseas arm’ for Immigration Enforcement – the Home Office agency responsible for detecting and removing people who have broken the state's immigration rules and procedures (HM Government 2016). In 2015, the UK had 188 liaison officers working in 45 cities in 36 countries, but refused to identify the number of personnel per country (Ostrand FOI 40413). This deep secrecy over external immigration activities perhaps explains why there is virtually no research on liaison officers’ on-the-ground operations. Although liaison networks are namechecked from policy documents (Mau et al Citation2012; Scholten Citation2015; FitzGerald Citation2019), no studies examine: the activities and efficacy of personnel abroad; how liaison efforts are implemented in specific ‘sending/transit’ states; and factors that shape variations in activities across foreign states. Original data is collated from 20 interviews with Home Office officials, Freedom of Information (FOI) requests, and research on primary and secondary official documents. Given a lack of transparency around extraterritorial migration activities, gathering this information was challenging.

Moving beyond limitations of bi-lateral case studies, we discuss liaison officers’ activities in five countries: France, the USA, Thailand, Egypt and Ghana. All countries are significantly large and populated that they have some potential for ‘push back’ against the UK's immigration goals, should they wish to. However, our selection allows comparison across variations by region, degree of political interconnectedness, historical and cultural ties, economic development and interdependency. The UK joins fellow wealthy nation-states France and the USA in numerous intergovernmental initiatives (EU with France before Brexit; NATO) leading to significant reciprocal cooperations in immigration and security matters. By contrast, Egypt and Ghana are less economically advanced lower-middle-income developing nation-states in Africa. They are former British colonies, but Britain defines them as ‘high risk’ sources for ‘unwanted’ immigration and makes efforts to implement control measures, as the more powerful partner in an unequal relationship. Finally, Thailand is an upper-middle-income developing nation-state with which Britain has few institutionalised intergovernmental ties, and no tradition for direct colonial rule. However, Thailand experiences massive flows of foreign nationals moving in and out each year – including 38 million tourists (Statham et al Citation2020; UNTWO 2019). Thailand is perceived as an important ‘transit’ country for people moving to the Global North.

We find important variations across the UK's efforts to implement extraterritorial measures in foreign states. However, an important general finding is that because liaison officers everywhere have to work on-the-ground in an environment where formal authority is retained by the foreign state, they have to engage significantly in ‘soft power’ persuasion tactics to try and achieve UK goals. In effect, this gives officers considerable discretion and autonomy in their actions. It means that the practical implementation of measures is relatively open to influence by officers’ decisions, evaluations and initiatives on location, but also by their foreign counterparts, and the quality of relationships they are able to establish with them. So ‘remote control’ is de facto less controlled than the image depicted by UK policy statements, designed for domestic consumption, and more open to mid-level officials’ agency, unintended ‘outcomes’, and happenchance occurrences.

The next section places our approach within extraterritorial migration management perspectives. We then present an analytic descriptive model that identifies the relationships between states and actors, and locates the actor field between liaison officers and their foreign counterparts, that we argue is influential in shaping ‘outcomes’ on-the-ground, and providing influential ‘feedbacks’ for UK policy decisions. This framework provides the basis for us to compare variations in these relationships across the countries in our empirical study. Finally, our concluding discussion re-evaluates ‘remote control’ perspectives alongside key findings.

Extraterritorial migration management

Most research on how governments try to regulate international mobility through interventions outside their sovereign territories is written from a destination state's perspective and focuses almost exclusively on restrictive measures (Boswell Citation2003; Gibney Citation2005; Lavenex Citation2006; Nethery, Rafferty-Brown and Taylor Citation2012; Ryan and Mitsilegas Citation2010; Zaiotti Citation2016). Studies look at: first, a state's decision-making leading to domestic policy goals for managing migration through restrictive immigration controls located abroad (e.g. Boswell Citation2003); or second, a state's efforts to establish immigration control mechanisms in countries perceived as an ‘immigration risk’ (e.g. Zaiotti Citation2016). The one-sidedness focussing on restrictions forgets Zolberg’s (Citation1989:408) famous dictum that migration management involves not only erecting ‘walls’ but also ‘small doors’ that allow selected migrants to enter. Typically, extraterritorialisation is studied as a government strategy by a receiving state to achieve its immigration objectives (within domestic politics), while foreign sending and transit states are reduced to relatively passive or powerless ‘policy-takers’ or a background contextual factor.

The story is almost always told from a Global North liberal nation-state's perspective, that sees itself as a destination for ‘unwanted’ immigration from a source or transit state in the Global South.Footnote2 In fact, our study shows extraterritorialisation efforts are not just between stronger and weaker states, but also occur between powerful states who have a more equal relationship, for example, when the UK established a liaison network in New York to combat ‘unwanted’ immigration from the Caribbean and Central and South America. With a few exceptions (FitzGerald Citation2019:101–122; Tittel-Mosser Citation2018; Wolff Citation2016), another problem is that agency is attributed almost exclusively to powerful destination states.Footnote3 Thus Hathaway and Gammeltoft-Hansen (Citation2015:243) consider sending and transit states ‘conscripted’ … ‘to effect migration control on behalf of the developed world’. While Lavenex (Citation2006:30) talks about cooperation with non-EU states as another ‘venue’ for interior ministries in Europe to ‘escape from internal blockades’ and implement restrictive immigration policies. Importantly, few efforts include foreign states’ and officials’ agency.

FitzGerald’s (Citation2019/Citation2020) state-of-the-art contribution importantly advances ‘remote control’. First, he includes extraterritorial measures within today's global system of immigration management, rather than as exceptional to ‘normal’ activities at a state's sovereign borders. ‘Migration control takes place on a continuum of space, from the most remote practices half a planet away down to walls at the state boundary, where remote control merges with border line control’ (FitzGerald Citation2020:5). Second, applying the ‘hierarchy of sovereignty’ concept (Lake Citation2009), he argues that while nation-states, as institutional forms, continue to monopolise the legitimate means of movement, some individual states do not monopolise control within their own territories. As a result of increasing interdependency in a world of nation-states, the exercise of sovereignty by nation-states has become ‘messy’, with powerful states calling the shots (2020:16): ‘Rather than each nation-state exercising full practical sovereignty over its own territory, there is a ‘hierarchy of sovereignty’ (Lake Citation2009) in which more powerful states exercise considerable influence over migratory movements from and through other states’ territories’.

FitzGerald places ‘remote control’ within a system of interdependent nation-states characterised by asymmetric power relations between powerful destination states, and weaker transit and source states, which leads to a shared coercion of movement. This importantly moves beyond earlier ‘remote control’ perspectives by recognising that available migration pathways are shaped by global interdependencies of nation-states and inequalities. However, his study stops there. It retains the bias that powerful destination states can largely get their way with transit and sending states. But this remains an assumption not interrogated by further analysis. Like many studies, there is a reliance on taking what policies say they do at face value and few details on the mechanisms through which interactions between destination, transit and source states are mediated by officials on-the-ground. In this contribution, we aim to add detail on these mechanisms by studying liaison officers’ and foreign officials’ agency, and their interactive relationships, as important factors that shape different ‘outcomes’ across countries.

Several scholars address the policy adaption of transit and source states in response to persuasion techniques, diplomatic pressures and financial incentives by powerful states, and the European Union (Lavanex and Ucarer Citation2004; Flynn Citation2014; Geddes and Taylor Citation2015; Nethery, Rafferty-Brown and Taylor Citation2012). However, few study the reverse relationship: how demands by transit and source states shape destination states’ policies and practices. One field that acknowledges some impact by source and transit states is EU bi-lateral agreements. Analysing the impact of external countries on EU states’ efforts to deport migrants, Ellermann (Citation2008) shows how the relative willingness of foreign authorities to cooperate sets boundaries for actions by member states. Specifically, she explains policy failures by ‘the refusal of many foreign governments to cooperate in the control efforts of advanced democracies’ (Ellermann Citation2008:169). In addition, Wolff (Citation2016:89) finds domestic and regional politics in Turkey and Morocco importantly shaped their motivations to agree to readmission agreements: ‘(they) are not passive actors when confronted with the externalisation of border controls and are able to influence to some extent the EU’ (see also Tittel-Mosser Citation2018).

Another important contribution by Ellermann (Citation2008) is she demonstrates that studying the formal policies of bi-lateral agreements says relatively little about what actually occurs on-the-ground when officials try to implement extraterritorial measures. Ellermann finds EU efforts to work effectively with foreign nation-states are still problematic after state-level agreements are signed. This matters because extraterritorial migration research usually focuses on negotiations that lead to the ‘outcome’ of an inter-state agreement, but fails to examine how efforts to implement agreed policies play out in the social world. This often leads to ‘outcomes’ that are different from objectives stated in policy agreements. Ellermann (Citation2008:180) shows how German ‘street- and mid-level interior bureaucrats’ pursue informal strategies with their foreign counterparts: they work with ‘like-minded foreign law-and-order bureaucracies’ to circumvent conflicting state-level interests over readmission agreements. In this way, German officials address non-complaint behaviour with an agreement by establishing ‘strategic relationships’ and seeking assistance from their foreign counterparts. This bypasses ‘the conventional diplomatic route’ and allows immigration officers scope for agency by ‘effectively eliminat(ing) … a level of decision-making marked by incongruent policy preferences’ (2008:181). These findings matter because they show: first, incentives, diplomatic pressure and inter-state policy agreements are not always sufficient to produce meaningful effective relationships with foreign states and officials; and second, establishing meaningful practical working relationships between mid-level officials, that are informal, based on ‘social capital’, can provide more effective channels for implementing policy objectives than formal channels.

Many studies on extraterritorial migration management underestimate how difficult it is even for a powerful nation-state to implement policy objectives on foreign territories, where it has no formal authority, is dependent on foreign state agreement to establish a presence, and has to try to implement this approach in the social world by cooperating with foreign authorities, while facing local conditions. Powerful states cannot simply impose their will over weaker ones by force, like in colonial times. Also, there are few attempts to study how ‘street-level’ negotiations between mid-level officials representing states can lead to the implementation of extraterritorial controls, or not. We aim to counterbalance these deficits.

First, it is important to acknowledge the power of foreign states acting on their own sovereign territories to shape ‘outcomes’. Whatever a destination state's intentions and policy goals are, they have few chances of success unless a foreign state deemed an ‘immigration risk’ has incentives to cooperate. At a general macro-level, motivations for inter-state cooperations may come from political and historical ties (colonial ties), economic interdependency (trade agreements, tourism, aid), or shared participation in inter-, multi- or supra-national institutional frameworks and agreements (e.g. EU, NATO). However, international relations are driven by factors that are largely external to migration-specific issues. This means any pathway towards achieving desired cooperation over migration is highly dependent on external and contingent factors. For example, the UK sees Libya as ‘high risk’ but bi-lateral relations are so weak they provide no basis to establish meaningful cooperation over migration on Libyan soil.

Second, even if foreign states formally agree to cooperate, implementing extraterritorial measures leads to further steps that importantly shape ‘outcomes’. Immigration liaison officials posted abroad lack formal legal authority to act on their policy goals. They are dependent on their ability to establish meaningful working relationships with their foreign counterparts in local immigration authorities and police. They draw on informal relations and ‘soft powers’ of persuasion. In effect, they operate like ‘street-level bureaucrats’ (Lipsky Citation1980) on-the-ground taking autonomous decisions in response to unexpected or uncontrollable circumstances.Footnote4 Even when there is a bi-lateral agreement, the unwillingness of their counterparts, or general factors, such as corruption or poor infrastructure, can hinder implementation. An important innovation of our contribution is to include liaison officers acting as ‘street-level bureaucrats’ within the equation for a state's external immigration control efforts. The model presented next locates where this agency fits in, alongside foreign states’ and officials’ agency, to influence the UK's extraterritiorial migration management policy process and ‘outcomes’. Perhaps deterred by the secrecy around liaison officers, other studies have failed to include their agency as a potential factor.

An analytic model for locating liaison officers’ and foreign officials’ agency within the UK's extraterritorial migration management

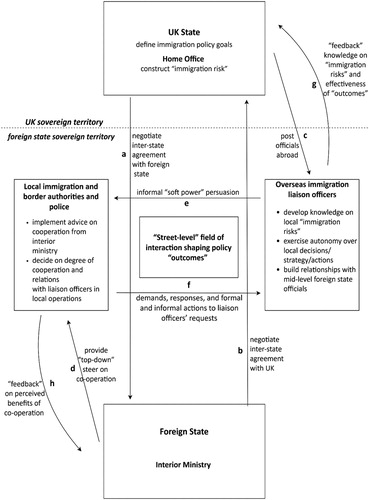

presents an analytic model that links the inter-state institutional level of policy agreements to the on-the-ground level of agency and interactions by mid-level state officials, who try to implement their respective state's migration objectives. The aim of the model is to show where ‘street-level’ agency occurs beyond ‘remote control’: it identifies the relationships between the UK and a foreign state, and the actor field that is subsequently constructed by agency between liaison officers and foreign state officials, who work together in relatively more or less cooperative relationships, to enforce the UK's migration policy objectives on-the-ground. In this way, it locates where key decisions and actions take place, that are not the exclusive remit of a destination state government operating from within its own sovereign territory. Rather we see that actions in the social world, outside a destination state's jurisdiction and control, have substantial bearing on its extraterritorial management. Importantly, the model introduces a level of decision-making and agency that is largely overlooked -by UK and foreign state ‘street-level bureaucrats’- and demonstrates the relations through which this can potentially influence policies and ‘outcomes’ to a greater or lesser degree. It defines liaison officers’ agency as: trying to define, initiate and implement UK policies on-the-ground; and providing ‘feedback’ that influences UK policy-making. In the empirical part, we examine the relationships identified in the model to compare the UK's extraterritorial migration efforts in France, the USA, Thailand, Egypt and Ghana.

Figure 1. An analytic model for locating liaison officers’ and foreign officials’ agency within the UK's extraterritorial migration management.

The logical starting point is the UK state, where the Home Office constructs and defines perceived ‘immigration risks’ for specific countries, acting within a domestic politics shaped by a government's immigration objectives. After ‘immigration risks’ are specified for a foreign state, a decision is taken over whether to support the strategy by remote actions. Such decisions to negotiate inter-state agreements are shaped by international relations and depend on political, economic and historical ties between the UK and a foreign state (a and b). International relations can be relatively equal, based on reciprocity, in cases where there are strong institutionalised political interdependencies, they are advanced economies, have strong historical ties, and share common immigration goals towards less developed countries (USA, France). Relationships can also be asymmetrical when the UK is higher in the ‘hierarchy of sovereignty’, and foreign states are lower-middle-income developing countries, former colonies, retaining Commonwealth political associations (Ghana), or rejecting them (Egypt), and whose migration-specific decisions are made within a relative political and economic dependency. Sometimes the UK decides to post officers in states it sees as transit hubs for ‘unwanted’ migration, but with which it has relatively weak historical, economic and institutional ties (Thailand).

For the UK to achieve an inter-state agreement and place liaison officers on a foreign state's sovereign territory (c), a foreign state has to see sufficient self-interest from supporting the UK's proposed migration control measures. While cooperative arrangements between Global North states are relatively equal, reciprocal and based on mutually perceived benefits, the UK may offer aid, preferential trade agreements, or political and military support, to incentivise a Global South state to cooperate. Once an inter-state agreement has been negotiated, a foreign state has to initiate implementation by issuing directives to local state authorities that regulate population movements on its territory (interior ministry, police, and immigration and border agencies) (d).

This creates a situation whereby two sets of officials, one from the UK, and one from the foreign state, interact at the ‘street-level’, having received directives with regard to objectives from their respective state ministries. Because UK immigration officers lack legal authority to enforce immigration controls abroad, they must reach out and build effective informal ties with their counterparts (e), who possess formal authority to implement policy measures. Foreign state officers respond to these initiatives (f), by exerting agency, and conducting actions that meet the UK's policy goals, or do not. The degree to which this is likely depends on the quality of the relationships established by liaison officers with their counterparts, and the relative willingness of their counterparts to act. External conditions can also hinder effective cooperations regardless of intentions, for example, when foreign bureaucracies or police are poorly resourced or ‘corrupt’. Foreign partners thus need to be both willing and able to implement measures recommended by liaison officers.

Importantly, this is a very long chain of command, that is not direct, and open to interventions and circumstances well beyond the Home Office and its liaison officers’ control. ‘Outcomes’ on-the-ground can be strongly influenced by liaison officers’ personal abilities, the willingness, abilities, and personalities of their counterparts, and interpersonal relations. In addition, liaison officers also have an important role 'feeding back' (g) evaluations of perceived ‘immigration risk’, analyses and assessments of efficacy on-the-ground to the Home Office. This can importantly shape the UK's migration management policy decisions, with respective to a specific country, and generally. For example, the decision to end the presence of liaison officers in New York, in 2017, resulted from ‘feedback’ from below, not a top-down initiative. This importantly shows that information and strategies also move in the opposite direction to that implied by ‘remote control’ narratives. Finally, just as liaison officers monitor the value and efficacy of relationships with their counterparts abroad, so police, local authorities and foreign state officials ‘feedback’ (h) to their interior ministries, on whether cooperations meet intended goals. This can lead to changes in approach by a foreign state's higher-level bureaucrats and influence their willingness to support further cooperations.

Method and data

This research is based on twenty semi-structured interviews with current and former Home Office officials, between July 2016 and Oct 2017. The interviewees were primarily mid- and lower-level civil servants who had experience working abroad and with foreign state actors, including (but not limited to) immigration and law enforcement officials from Ghana, Egypt, Thailand, the USA and France. The interviewees were selected based on their familiarity with overseas operations, especially the liaison network. All interviewees had experience in managing and/or implementing extraterritorial controls. Despite efforts, we were unable to obtain interviews with foreign state actors. Our analysis thus focuses on Home Office officials’ perceptions of the liaison network's effectiveness and foreign officials’ willingness to cooperate. Given secrecy surrounding Home Office activities, and commitments made to interviewees, we are restricted in information we can report to preserve anonymity. provides limited information on the sample. We cite the letter corresponding to an interviewee to indicate a source.

Table 1. Interviews with current and former Home Office officials, July 2016–October 2017.

The interviews are supported by original FOI requests, documentary research on primary and secondary legislation, explanatory memorandums, impact assessments, Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration (ICIBI) reports, and UK policy papers and press releases (). Information from interviews and FOI requests are all original data sources previously unavailable in the public domain. They were hard to retrieve. While UK Home Office documents cite general objectives of the liaison network, there is virtually no public information on what liaison personnel actually do in specific countries, who they work with and where they have police referral programmes. Importantly, our original sources allowed us to go beyond existing literature which has relied almost exclusively on policy documents and interviews with high-placed civil servants. By contrast, our approach draws largely on operational mid-level actors’ perceptions of their agency and effectiveness. Importantly, this allows us to take into account the social world of local conditions and on-the-ground relationships with foreign state officials as factors that have consequential effects.

Table 2. Cited official sources, documents, and freedom of information requests.

Negotiating inter-state agreements

We start from the Home Office's decisions to implement extraterritorial migration management. Such efforts are part of an overall strategy to limit and control immigration and reduce perceived costs of legal obligations for deporting ‘unwanted’ migrants on British soil: ‘[i]t is better to control entry before arrival, as far away as possible, given the extra difficulties removal from the UK territory can present’ (HO 2005:25). Operating within a domestic politics, where governments publicly prioritise immigration control, the Home Office mobilises to identify, perceive and define ‘immigration risks’.

The liaison network of overseas immigration officers is an important, but relatively hidden ‘tool’ in this effort to control migration. Liaison officers support the UK's efforts to implement control through visas by active interventions on-the-ground, including identifying inaccurate information and forgeries, and working with airlines and foreign authorities to prevent ‘unauthorised’ movement. They also provide risk assessments ‘identifying threats to the UK border’ by collecting and analysing data on migration-related trends and foreign states’ control capacities (A, F, T; Vine 2014:30). Liaison officers’ knowledge production 'feedsback' into the Home Office's approach to defining perceived ‘immigration risks’ and implementing control measures in specific foreign states. For example, a Home Office report documents how new restrictive transit visa requirements were introduced for Syrians, Libyans and Egyptians based on information provided by liaison officers (HO 2011:3 and 4).

Prior to implementing control activities, the Home Office has to negotiate agreements with foreign states to host UK officials on their soil. From the UK state's perspective, the aim is to place liaison officers in countries where perceived ‘immigration risks’ of ‘unauthorised’ migrants moving to the UK are sufficiently high to require interventions that support an effective visa system. ‘(E)verything the (network does) is always dependent on what the threat is to the UK … we focus on the areas where there is more risk and need’ (U). The Home Office is highly secretive about its assessments of ‘immigration risk’ and the criteria and data sources used to legitimate their decisions (e.g. Ostrand FOI 46078). Interviews and several documents, however, suggest ‘risks’ often relate to a perceived likelihood for ‘unwanted’ immigration, especially potential asylum seekers and visa overstayers who are framed as ‘abusing’ the UK's rules and procedures, and to a much smaller degree ‘crime’ and ‘security’ concerns, including ‘smuggling and trafficking in persons’ (A, D, M; T; Home Office 2011; Vine 2011, 2014).

With regard to global spread, the Home Office aims to be systematic and implement a coordinated network of liaison officers to meet policy goals: ‘All the key exit points toward the UK, we have got offices there. We operate where there is a need to operate … We don't operate in countries where we have no migration threat and there is no visa operation’ (T). It is also clear that the UK's ‘risk’ perceptions are dynamic and liaison officers’ ‘feedback’ strongly informs and shapes adaptions: ‘(W)e move offices when we see the threat change’ (T).

Once the Home Office identifies a perceived ‘need’ to place liaison officers in a country, inter-state level negotiations are initiated with the foreign state. Important criteria that shape possibilities for cooperation agreements are established political, economic, and historical relations between the two states. The UK finds it relatively easy to implement liaison officers on sovereign territories of foreign states like France and the USA, with which it has strong historically established institutionalised channels for cooperation over migration and security – e.g. EU (France); Five Country ConferenceFootnote5 (USA); NATO (France and USA) – and shares common goals on most aspects of migration control from the Global South. A Home Office official confirms this spill over of common shared interests and historically established cooperations: ‘(W)e are all accustomed to working with each other in all other formats: political, military, counter terrorism, law enforcement, not just immigration. Historic ties and longstanding MoUs (memorandums of understanding) are also a decisive factor’ (C). However, it needs stating that shared common interests over immigration, though great, remain relative not absolute. EU member states sometimes attempt to ‘burden shift’ to one another, with regard to accepting ‘unauthorised’ migrants and resultant legal responsibilities. In such instances, EU states’ interests compete. The UK's liaison presence in France is one of its largest globally precisely because the Home Office perceives it as a key transit country for ‘unauthorised’ immigration from the Schengen area (Cabinet Office 2007:40; F, H, L, Q, T).

By contrast there are states with which international relations are weak, or where the country is unstable or dangerous, e.g. Eritrea, Iran, or Libya, so that the Home Office sees few chances of posting liaison officers, although they are defined ‘high risk’. In such cases, the UK seeks out potential agreements with nearby states. For example, an officer recounts how more personnel were located in Egypt in 2015 because the Home Office perceived irregular immigration via North African routes to be increasingly problematic, ‘mainly in Libya but we could not go there so we had to work from Egypt’ (P).

Between highly established cooperations, and states where the UK has poor international relationships, there is a middle-ground of countries, mostly from the Global South, which the UK state tries to incentivise to allow liaison officers on its territory. Historical and political ties still come into play. Of the twenty-five non-EU, non-NATO countries where the Home Office had liaison officers in December 2015, ten had political relationships as Commonwealth members (Ghana), while a further five had historical ties as former colonies, but not Commonwealth members (Egypt). Other bases for the UK to build shared interests and reciprocity with states are from, first, perceived benefits through economic trade relations, including possibilities for development aid, and second, by the UK offering knowledge exchanges, training and equipment to improve a foreign state's security measures. Less wealthy countries are considered likely to want to cooperate because they are ‘interested in access to the British trade market and in learning from the UK's expertise in immigration and border security’ (E).

The formal inter-state agreement the Home Office secures with a foreign state is essential in determining the potential degree and type of operations for liaison officers abroad. Foreign governments and interior ministries have to authorise their presence on their sovereign territory and international airports in their jurisdiction (F; Ostrand Internal Review FOI 40413).Footnote6 The legal limitations of their own authority are very clear to liaison officers: ‘Yeah, we have no legal powers overseas. So, you do what you do in that location as the guest of whoever is the leadership of that country’ (T). This means that a foreign government's and interior ministry's top-down steer to its local authorities, police, and immigration services is of tantamount importance and shapes the depth and type of possible cooperations with UK liaison officers. Several interviewees (L, I, T) confirm the importance of foreign governments’ and senior officials’ support for getting a meaningful foothold on foreign soil. One calls this support ‘political buy in’: ‘Getting the political buy in is absolutely crucial … If the political will is there at least you can make some inroads, maybe not as deep as you would like but you can make a start’ (I). Another confirms: ‘(A)bsolutely, if the political will is there then the (police and immigration) authorities are more willing and interested’ (L).

A tangible feature of a foreign state's relative ‘political buy in’ is whether the Home Office is able to formally agree a Police Referral Programme (PRP), that allows UK personnel to share intelligence with local law enforcement agencies on individuals suspected of participating in, or facilitating, ‘unauthorised’ migration (Vine 2010). According to PRP agreements, immigration officials and police are expected to use information supplied by UK officers to investigate and prosecute implicated individuals. Importantly, from a ‘remote control’ perspective, these agreements are the Home Office's attempt to enforce punitive juridical actions against people they suspect are ‘unauthorised’ migrants’, or supporting ‘unauthorised’ migration on foreign soil. A Home Office official highlights the importance of PRPs: ‘What you have to understand is that if you found criminality, you want to bring it to the local authority (otherwise) nothing happens, there are no consequences and nothing to deter them from trying again’ (O).

With states like the USA that are close allies, PRP agreements are relatively easy to establish within already strongly shared immigration cooperations. For EU countries, like France, PRPs are not needed because there is already an institutionalised mechanism that serves an equivalent purpose (M). In December 2015, the Home Office had PRP agreements with 15 non-EU states, though refused to disclose which ones (Ostrand FOI 42049; Ostrand Internal Review FOI 40413). Nonetheless, from interviews and by reviewing reports, we know that for our cases PRPs existed in New York, USA (Vine 2011: 39), Accra, Ghana (HO and FCO 2010: 16; I), and Bangkok, Thailand (A, U), but not Egypt (L).

Overall, foreign states are able to ‘push back’ and exert considerable agency over the UK's extraterritorial efforts. Their relative motivation to work with the UK is determinant and derives from their specific pre-existing international relations, economic dealings, and perceived mutual benefits from cooperation. This important background context on the depth and type of inter-state agreements foreign states are willing to accept, importantly shapes the UK's opportunities for effective liaison operations on-the-ground.

Liaison officers working with foreign officials: ‘street-level’ interactions

When inter-state agreements allow the operational presence of UK officers, we reach a situation where, on one side, liaison officers attempt to implement immigration measures on foreign soil, while on the other, local authorities, immigration services and police, act on the directives of their interior ministries to support liaison officers’ initiatives. This step from formal inter-state agreements to what actually happens on-the-ground is a long one that is strongly shaped by decisions and interactions between mid-level officials from both sides. Though understudied, it is important to make this link between the inter-state and ‘street-level’ exchanges. Here we study the UK's extraterritorial efforts in the USA, France, Thailand, Ghana, and Egypt to compare how the type, depth and quality of relationships on-the-ground shape how it works, whether it is effective, and factors that account for ‘outcomes’.

A first important point is liaison officers possess a high degree of autonomy and discretion in pursuing their own strategies for immigration management locally. The Home Office does not have established extraterritorial interventions which it intends to implement in a country. Much of what the UK's liaison network does in a specific state is decided in that country. To achieve their policy goals, liaison officials make judgments about where they see greater ‘immigration risks’ and ‘need’ for action (D, E, M, O, T, U). Liaison managers use this information to develop specific strategies to address perceived areas of local ‘need’. ‘(Activities are) pretty much decided by the (liaison manager) in the country because you know what your current threats are, what is the continuous problem you keep seeing’ (U). Contrary to ‘remote control’ metaphors, here we see key decisions about the UK's extraterritorial interventions are open to interpretations and agency by mid-level officials located abroad, rather than made by the Home Office from within its own sovereign territory.

A second important point is a liaison network's strategic aims must be reconciled with the local context and constraints in a given country, especially the relative willingness of foreign officials to cooperate. They consider ‘success’ depends on their ability to form good relationships with local authorities, and develop joint initiatives, that fit their perceptions of British ‘needs’ in the local context (E, F, I, L, O). A primary role is ‘liaising’ with foreign officials, to create opportunities to work with local immigration and law enforcement agencies (A). Importantly, liaison officers’ activities are the product of negotiations and compromises with their local counterparts: ‘We work and build relationships in a country, but they also work with us … In fact, I think it is a two-way street’ (T). In countries where liaison officers have good relationships with local officials, they meet regularly to discuss what their counterparts want to improve, and aspects of migration control and law enforcement that fit UK objectives (E, I, O, T). Interviewees emphasise that interpersonal skills and cultural awareness are crucial attributes (F, I). A job advertisement underlines this stating it ‘requires someone with excellent interpersonal skills in order to build effective working relationships with … (liaison network) regional teams, UK teams, and external partners’ (HM Government 2016).

Liaison officers think a key to their ‘success’ is establishing trust and familiarity in working relationships with local authorities and police, so that they can try to be effective in the absence of formal legal power. A Home Office official highlights that a ‘high degree of trust’ is necessary ‘to get to the real issues without worrying about offending and tarnishing the relationships’ (E). This shows the importance for liaison officers of building ‘social capital’ on location, that bridges to their foreign counterparts, as a resource to be effective. In some cases, local officials seek out liaison officers and request training, resources and capacity building support (E, I, O, T). An officer recounts, ‘(w)e are open to that’ (T), while another confirms ‘(w)e will train anyone who needs it, to be honest’ (O). For example, liaison officers provided ‘tailor-made trainings’ in ‘human trafficking’, document authenticity and investigative skills at the request of Ghanaian officials to meet domestic goals (I). This demonstrates local officials are able to exert agency by bargaining with liaison officers, in ways that shapes ‘outcomes’ on-the-ground.

Overall, we found liaison officers employ ‘street-level’ diplomacy, ‘soft power’ and incentives with their counterparts on-the-ground to try and reach their objectives. Negotiations tend to be relatively low-level, localised, and personal: ‘You wouldn't normally tell someone they are inefficient in certain ways when you are coming through and you are developing projects with the local law enforcement partners … So, you know, you might get a shopping list of equipment and we say ‘actually we are not in position to fund that. But what we can do is provide the following which will give you the capability to do that without the equipment’’ (T).

‘Outcomes’ on-the-ground are strongly shaped by the relative receptiveness of local authorities and police to their overtures. In the USA and France, Home Office officials explain very high levels of cooperation on their mutual trust with officials, good working relationships, and shared view that cooperation was mutually beneficial to policy goals. Historical legacies of cooperation, frequent meetings and institutional mechanisms associated with the EU and the Five Country Conference also facilitated greater collaboration (A, C, E, M, T). The EU, for example, has an arrangement allowing officers to exchange information with police from any EU country (M). However, on-the-ground cooperation is very high, not absolute. Notwithstanding high levels of information-sharing between UK officers and local French immigration and law enforcement, including joint investigations and enforcement (Brokenshire 2015; M), France is still defined an ‘immigration risk’ for 'unauthorised' transit migration travelling through the Schengen area. There are a large number of French regional airports with regular cheap flights to UK destinations and the Home Office perceives that officials working at these airports lack the resources, skills and motivation to conduct effective document checks (D, M, Q). One official even claimed personnel at regional airports in France sometimes ‘turn a blind eye’ to ‘unauthorised’ migrants leaving the country because they prefer them to move to Britain (M).

Generally, in developing countries the UK's efforts depend much more on officers’ abilities to establish semi-formal relations with their counterparts. The potential effectiveness of liaison officers is importantly shaped by the foreign local authorities’ perceived benefits of cooperation. Interviewees recount how officers in ‘some countries have a fantastic relationship because law enforcement does absolutely everything for them, and they want that kind of close engagement’ (U), while in others, ‘they are just not interested’ (O). Although liaison officers strive to form good working relationships and elicit effective cooperation from local authorities in developing countries, their foreign counterparts’ perceived interests are beyond their control, and subject to external and contingent factors.

Egypt's postcolonial relationship with the UK has often been strained, it remains outside the Commonwealth. A Home Office official recounts how the Egyptian government rejected the UK's attempts to initiate a PRP with the claim ‘we don't want to cooperate. There is nothing in it for us’ (I). Subsequently, liaison officers’ efforts to establish training and enforcement initiatives failed ‘due to the lack of political will’, which meant local ‘authorities just did not cooperate’ (L). Clearly, in cases where inter-state relations are weak, working on-the-ground is much harder. So, Egypt has no PRP and receives no training by liaison officers. Despite officers’ strong efforts, ‘(i)t was difficult to do that with Egyptians: they did not want to engage’ (P). As a result, fraudulent documents are not confiscated, incidents not investigated, and perpetrators not held accountable (O). This highlights how important support from local foreign authorities is for liaison officers to be effective. As one underlines: ‘(I)f you are not actually working with the people, the local authorities, and you get a situation where (an airline refuses boarding), then nothing else happens … no one is taking the forged documents or looking at the crime groups behind what's going on … there are no consequences and nothing to deter them from trying again’ (O). When relations with local authorities are poor, liaison officers try to find other strategies. In Egypt, officers ‘had to get creative and look for other ways of working with various people, like having a better relationship with the airlines’ (I).

In stark contrast, official documents and interviewees document how the UK sees its relationship with Ghana as a ‘model’ for good working relationships on migration and border control – there is a PRP and especially good relations with the police and immigration agency (I; Cabinet Office 2007, 54; FCO 2010; HO and FCO 2010: 16; Vine 2012: 18). Ghana is a Commonwealth member, with a less fractious postcolonial relationship than Egypt. Generally, officers consider that Ghanaian state authorities see benefits in maintaining good relations with the UK, including more development aid, trade, and technical training, so cooperate on migration control (E, I, L). This high receptiveness of Ghanaian police and immigration officials allows liaison personnel a space to advance enforcement-related initiatives and ‘provides considerable scope to develop prevention and capacity building in Ghana’ (I). In fact, Ghana is the only state where ‘developing local capacity’ is a primary objective. Officers train Ghanaian officials in interviewing skills, profiling techniques, identifying inaccurate documents, investigative skills, intelligence use, and IT, and donate equipment to support investigations. In addition, officers helped their Ghanaian counterparts set up specialised units in human trafficking and immigration crime (I, S). A Home Office official explains Ghanian authorities’ motivations for cooperating on what he perceives as their interests in gaining increasing UK support: ‘if they cooperate then they are likely to get more assistance from us on building their (immigration and law enforcement) capability, and aid and assistance on other fronts. Also, it improves the business environment, improves the credibility … and probably development aid and trade’ (L).

Yet, even when high local cooperation is achieved, there are still contextual and environmental factors that can limit overall effectiveness. In Ghana, officials think the PRP is ‘working very well’, and ‘the police are regularly involved’, but also acknowledge that ‘the end result might not always be what we would desire’ (I, L). Specifically, the number of arrests is lower than the UK wants, and few result in prosecutions. One interviewee blames long delays and regular dismissals by courts, which he attributes to overextended detention facilities and justice systems. He also claims corruption by low-level officials in the government, police and courts impedes ‘successful’ outcomes (I).

Thailand is a significant location for the UK's extraterritorial efforts. This is not due to a Thailand-specific ‘immigration risk’, but because Bangkok hosts a large visa centre that also processes applications from neighbouring Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar and Vietnam (Ostrand FOI 44306; U), and a large international airport with a high volume of inbound flights from African and Asian countries that are considered ‘risks’ and many outbound flights to the UK (A, F). Thailand and the UK have a PRP agreement that demonstrates intent to cooperate. However, officers still trace what they see as limited effectiveness in implementing migration control measures and relatively poor relations with Thai police and immigration authorities back to relatively weak inter-state relations and divergent goals: ‘it is just not high on the Thai government's priority list’ (A). The Thai state is not involved in close multi-national institutional cooperative arrangements with the UK, nor is it a former colony, so there are few historical and political ties to build on. ‘(I)n Thailand we are not such a big player. We do not have so much influence … as we would in other countries (like) Ghana which is obviously a former Commonwealth country’ (U).

As a result, on-the-ground relations between UK liaison officials and their Thai counterparts are relatively poor, so that PRP objectives fail at the implementation stage. This example clearly illustrates that formal bi-lateral agreements tell us relatively little about what actually occurs in practice. As one official recounts: ‘(I)t is very difficult to get anything done here in Thailand … if we come across forgeries in the visa process, if we refer that information to the Thai police, um well nothing ever happens’ (U). The UK officials’ lack of trust in, and weak social capital with, the police means they resist sharing intelligence (A): ‘(T)he … thing in Thailand is about trust. It is a continuous change of commanders … and … sometimes we will have information we give to them and we ask them that the information is not for disclosure to the public or during an investigation and they still tell people. So that is why we are wary of what kind of cooperation we give’ (U).

Liaison officers’ effectiveness is also limited because Thai priorities on migration management do not coincide with the UK's goals. An interviewee, for example, claims the Thai immigration agency ‘doesn't really care who is leaving their country’, so officers concentrate their training efforts ‘on who is entering the country on (forged) UK documents’, which is a shared interest: ‘(T)hat is all we can do … (immigration authorities) only care about who is coming in’ (U). Once again, we see foreign state actors exerting agency on the UK's extraterritorial migration management efforts, compelling liaison officers to negotiate and make compromises that reflect others’ interests and priorities. Finally, liaison officials encountered environmental factors that made it hard to collaborate, especially IT systems incompatible with the UK's that made it hard to share information on false documentation.

Conclusion

This study provides a necessary counterbalance to understandings of how extraterritorial migration management ‘works’. It challenges core assumptions of the highly influential ‘remote control’ framing. We consider claims in ‘remote control’ perspectives that ‘outcomes’ of migration management policies implemented abroad are largely a semi-automatic result of the government's and Home Office's agency in the UK, exaggerated and even false. Against this, we find there is a very long chain of decisions and actions, by foreign and UK state actors, operating at different levels, not least the ‘street-level’ on foreign soil, as well as uncontrollable circumstances, that shape possibilities for UK officers to be ‘effective’ in implementing policy goals abroad. While ‘remote control’ invokes a simple one-way causality, policy implementation turns out to be ‘messy’ in the social world. It is open to numerous factors beyond the Home Office's control, so that policy ‘outcomes’ are sometimes remote from a state's intentions. ‘Remote control’ perspectives start with the view that powerful Global North destination states are primary agents and ‘in control’, but seldom interrogate this assumption. This is problematic because governments from powerful states construct myths over their ability to ‘control’ immigration specifically for public consumption within their domestic politics. Researchers adopting this idea of ‘control’, uncritically, perpetuate this ideology. Instead our findings show that the idea that the Home Office exercises ‘control’ by extraterritorial measures is factually very much an overstatement.

First, our findings demonstrate liaison officers exercise autonomy over decisions and actions on foreign soil. They are primary agents implementing policies and have authority to respond to on-the-ground experiences and conditions as they arise. They lead in establishing ‘street-level’ working relationships with counterparts, which are essential to implement effective measures geared towards preferred ‘outcomes’. Although structured by specific conditions of inter-state relations, we also find policy ‘outcomes’ on-the-ground are open to happenchance and serendipity, in that they result from an officer's ability to build quality relationships and ‘social capital’ with counterparts. Another point is that liaison officers decisively shape UK extraterritorial policies by ‘feeding back’ opinions and assessments that significantly influence the Home Office's perceptions of 'immigration risk’. Here influence runs in the opposite direction to that implied by ‘remote control’. Liaison officers’ agency is largely unstudied, perhaps because the Home Office cloaks their activities in secrecy. However, decision-making by mid-level officials operating abroad matters a great deal for Home Office extraterritorial policies, both overall and for specific countries.

Second, foreign states are not just ‘takers’ of UK extraterritorial policies. Inter-state agreements and international relations between the UK and a foreign state shape a specific opportunity structure for cooperation over migration management. Our comparative study shows these vary considerably across foreign states, depending on historical, political and economic relations and common goals over controlling migration flows to the Global North. Once an inter-state agreement is made that allows UK officers to operate on a state's sovereign territory, the top-down steer foreign states give their authorities to support liaison officers’ goals, or not, importantly defines the scope for on-the ground cooperations and resultant ‘outcomes’. Much depends on a foreign state's mid-level officials’ willingness to work with their UK counterparts at the ‘street-level’, which is contingent on local factors, especially the quality of relationships. However, even when local authorities offer support, as in Ghana, there can be contextual factors – e.g. weak judicial processes – that limit effectiveness at the implementation stage. Foreign states’ and officials’ agency and the local context are largely missing from ‘remote control’ perspectives.

A final point is that today extraterritorial migration management is a ‘normal’ central component of a state's immigration control measures. Earlier research on bi-lateral cases studies depicted ‘remote control’ as ad hoc or exceptional to immigration control at a state's border. However, in an interrelated world of nation-states, available migration pathways are defined by a global system of migration management imperatives, which means that powerful states work together to routinely implement controls in transit and sending states (FitzGerald Citation2020). For research, it is increasingly important to understand a state's extraterritorial efforts relative to its place within a global ‘hierarchy of sovereignty’ of states controlling population movements. This requires expanding the conceptual lens by studying agency beyond the classic ‘remote control’ bi-lateral case study. Our study examines the UK's extraterritorial efforts across five states precisely to unpack variations that result from the UK state's place in a world system of migration management. We also show that liaison officers are substantively ‘street-level’ agents operating beyond ‘remote control’, by demonstrating how their agency on location – especially their interactions with foreign officials, and ‘feedbacks’ to the Home Office – influences the decisions, implementation and ‘outcomes’ of the UK's extraterritorial migration policies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 This article focuses on IEI activities (formerly RALON – Risk and Liaison Overseas Network). IEI is distinct from overseas Border Force officers –present in 11 countries in 2015 (Ostrand Internal Review FOI 43366) – whose wider remit includes ‘border security’ and ‘smuggling and trafficking in humans and contraband’ (J).

2 Exceptions include Bosworth (Citation2020) on UK–France ‘juxtaposed border controls’ and detention and Arbel (Citation2013) on US–Canada ‘safe third country’ agreements.

3 The recent study by Adam et al. (Citation2020) on migration policy-making in Ghana and Senegal is an important original contribution and exception in this respect. Their findings demonstrate that migration policy approaches in West African countries targeted by (EU) international cooperations are shaped by a dynamic interplay of international and domestic interests, and therefore need to be studied as ‘intermestic’ policy issues.

4 Ethnographic studies exist on immigration officials’ decision-making as ‘street-level bureaucrats’ in receiving countries (Eule Citation2018), but there is virtually nothing on immigration officials posted abroad (though see Infantino Citation2019 on visa officers).

5 The Five Country Conference is an informal group of immigration authorities from Global North states, the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the UK, that meets regularly and collaborates.

6 See also Section 4.2, 2002 International Airport Transportation Association code of conduct for liaison officers (IATA/CAWG 2002), which the UK legally follows (Madder FOI 28330).

References

- Adam, Ilke, Florian Trauner, Leonie Jegen, and Christof Roos. 2020. “West African Interests in (EU) Migration Policy. Balancing Domestic Priorities with External Incentives.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, Online Publication, 1–18. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1750354.

- Arbel, Efrat. 2013. “Shifting Borders and the Boundaries of Rights: Examining the Safe Third Country Agreement Between Canada and the United States.” International Journal of Refugee Law 25 (1): 65–86. doi: 10.1093/ijrl/eet002

- Boswell, Christina. 2003. “The ‘External Dimension’ of EU Immigration and Asylum Policy.” International Affairs 79 (3): 619–638. doi: 10.1111/1468-2346.00326

- Bosworth, Mary. 2020. “Immigration Detention and Juxtaposed Border Controls on the French North Coast.” European Journal of Criminology, doi:10.1177/1477370820902971.

- Ellermann, Antje. 2008. “The Limits of Unilateral Migration Control: Deportation and Inter-State Cooperation.” Government and Opposition 43 (2): 168–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2007.00248.x

- Eule, Tobias. 2018. “The (Surprising?) Nonchalance of Migration Control Agents.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (16): 2780–2795. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2017.1401516

- FitzGerald, David Scott. 2019. Refuge Beyond Reach: How Rich Democracies Repel Asylum Seekers. New York: Oxford University Press.

- FitzGerald, David Scott. 2020. “Remote Control of Migration: Theorising Territoriality, Shared Coercion, and Deterrence.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (1): 4–22. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2020.1680115

- Flynn, Michael. 2014. “There and Back Again: On the Diffusion of Immigration Detention.” Journal on Migration and Human Security 2 (3): 165–197. doi: 10.1177/233150241400200302

- Gammeltoft-Hansen, Thomas, and James Hathaway. 2015. “Non-refoulement in a World of Cooperative Deterrence.” Columbia Journal of Transnational Law 53: 235–284.

- Geddes, Andrew, and Andrew Taylor. 2015. “In the Shadow of Fortress Europe? Impacts of European Migration Governance on Slovenia, Croatia and Macedonia.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (4): 587–605. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2015.1102041

- Gibney, Mathew. 2005. “Beyond the Bounds of Responsibility: Western States and Measures to Prevent the Arrival of Refugees.” Global Migration Perspectives 22: 1–23.

- Infantino, Federica. 2019. Schengen Visa Implementation and Transnational Policymaking: Bordering Europe. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan US.

- Joppke, Christian. 1998. “Why Liberal States Accept Unwanted Immigration.” World Politics 50 (2): 266–293. doi: 10.1017/S004388710000811X

- Lake, David. 2009. Hierarchy in International Relations. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Lavenex, Sandra. 2006. “Shifting Up and Out: The Foreign Policy of European Immigration Control.” West European Politics 29 (2): 329–350. doi: 10.1080/01402380500512684

- Lavenex, Sandra, and Emek Uçarer. 2004. “The External Dimension of Europeanization: The Case of Immigration Policies.” Cooperation and Conflict 39 (4): 417–443. doi: 10.1177/0010836704047582

- Lipsky, Michael. 1980. Street Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Mau, Steffen, Heike Brabandt, Lena Laube, and Christof Roos. 2012. Liberal States and the Freedom of Movement: Selective Borders, Unequal Mobility. Basingtoke: Palgrave.

- Nethery, Amy, Brynna Rafferty-Brown, and Savitri Taylor. 2012. “Exporting Detention: Australia-Funded Immigration Detention in Indonesia.” Journal of Refugee Studies 26 (1): 88–109. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fes027

- Ryan, Bernard, and Valsamis Mitsilegas. 2010. Extraterritorial Immigration Control: Legal Challenges. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

- Scholten, Sophie. 2015. The Privatisation of Immigration Control Through Carrier Sanctions: The Role of Private Transport Companies in Dutch and British Immigration Control. Brill Nijhoff: Leiden.

- Statham, Paul, Sarah Scuzzarello, Sirijit Sunanta, and Alexander Trupp. 2020. “Globalising Thailand Through Gendered ‘Both-Ways’ Migration Pathways with ‘the West’: Cross-Border Connections Between People, States, and Places.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (8): 1513–1542. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2020.1711567

- Tittel-Mosser, Fanny. 2018. “Reversed Conditionality in EU External Migration Policy: The Case of Morocco.” Journal of Contemporary European Research 14 (4): 349–363. doi: 10.30950/jcer.v14i3.843

- Wolff, Sarah. 2016. “The Politics of Negotiating EU Readmission Agreements: Insights From Morocco and Turkey.” In Externalizing Migration Management: Europe, North America and the Spread of ‘Remote Control’ Practices, edited by Ruben Zaiotti, 89–112. New York: Routledge.

- Zaiotti, Ruben. 2016. Externalizing Migration Management: Europe, North America and the Spread of “Remote Control” Practices. London: Routledge.

- Zolberg, Aristide. 1989. “The Next Waves: Migration Theory for a Changing World.” International Migration Review 23 (3): 403–430. doi: 10.1177/019791838902300302

- Zolberg, Aristide. 1997. “The Great Wall Against China.” In Migration, Migration History, and History: New Perspectives, edited by Jan Lucassen and Leo Lucassen, 291–315. New York: Peter Lang.

- Zolberg, Aristide. 2003. “The Archaeology of ‘Remote Control.” In Migration Control in the North Atlantic World: The Evolution of State Practices in Europe and the United States From the French Revolution to the Inter-War Period, edited by Andreas Fahrmeir, Olivier Faron, and Patrick Weil, 195–222. New York: Berghahn Books.