ABSTRACT

Research has examined tolerance of Muslim minority practices and anti-Muslim sentiments. We go beyond the existing research by applying latent profile analyses (LPA) on majority member’s evaluations of a range of Muslim practices and their feelings toward Muslims. We found five different subgroups of individuals among a sample of Dutch majority members (N = 831): a group that is positive towards Muslims and their practices (‘positive’), a group that is negative towards Muslims and their practices (‘negative’), a group that rejects all Muslim practices but reports positive feelings towards Muslims (‘intolerant’), a group that rejects only some practices and also has positive feelings towards Muslims (‘partly intolerant’), and a group that is not positive towards Muslims but accepts one practice (‘partly tolerant’). Furthermore, we show that these subgroups differ on key psychological variables (authoritarianism, status quo conservatism, and unconditional respect), and in their feelings towards other minority groups and (in)tolerance of other non-Muslim practices. We conclude that majority members can combine feelings toward Muslims and (in)tolerance of Muslim practices in different ways, and that the LPA approach makes an important contribution to the literature by providing a more nuanced understanding of how the public views Muslim minorities.

Muslim minority citizens in Western societies want to freely express and practice their religiosity, try to establish suitable institutions for educational and religious activities, and seek to politically promote their interests (Haddad and Smith Citation2001; Helbling Citation2012). These goals and the related demands receive mixed reactions from the general public. It is one thing to agree with the general liberal notion that Muslims should be able to live the life they want, but another to accept Muslim practices, such as the founding of Islamic schools, the building of minarets, or the refusal to shake hands with someone of the opposite gender.Footnote1 There is typically a difference in how people evaluate general principles in comparison to concrete issues. Yet it is around concrete issues and practices that ways of life collide and the need for acceptance of cultural diversity arises.

Intolerance of Muslim practices has commonly been explained by how people feel towards Muslims as a group, with research indicating that people who reject Muslim practices tend to have anti-Muslim sentiments (e.g. Saroglou et al. Citation2009). For example, Blinder, Ford, and Ivarsflaten (Citation2019) found that Muslim prejudice is an important driver for opposing the accommodation of Muslim religious schools in Sweden, Norway, and Great Britain. Similarly, research showed that anti-Muslim sentiments underlie the support for banning the wearing of headscarves, Islamic education, and the building of Mosques (Helbling Citation2014; Saroglou et al. Citation2009; Van der Noll Citation2014).

Yet, (in)tolerance of specific Muslim practices does not always align with the way people feel towards Muslims (e.g. Adelman and Verkuyten Citation2020; Van der Noll Citation2014; Sniderman and Hagendoorn Citation2007). For example, among national samples in four Western European countries, a substantial proportion of people with positive feelings towards Muslims supported a ban on headscarves (Helbling Citation2014), and also objected to Islamic education in German public schools and the building of Mosques (Van der Noll Citation2014). In addition, some individuals with negative feelings towards Muslims have been found to be willing to support the appointment of a Muslim teacher (Van der Noll, Poppe, and Verkuyten Citation2010), the wearing of headscarves, Islamic education and the building of Mosques (Van der Noll Citation2014).

Whether people accept or reject particular practices can depend on the type of the practice rather than the specific group engaged in it (Helbling and Traunmüller Citation2018; Hirsch, Verkuyten, and Yogeeswaran Citation2019; Sleijpen, Verkuyten, and Adelman Citation2020). People might reject a specific practice (i.e. founding of Islamic schools) because they are negative towards Muslims as a group or because they disapprove of that particular practice in general (i.e. religious education; Bilodeau et al. Citation2018; Hurwitz and Mondak Citation2002). Similarly, people can accept a specific practice because of positive feelings towards the group or because of more practice-related reasons.

One way to examine these possibilities, and thereby go beyond the existing research, is to simultaneously consider group-based feelings and a range of Muslim practices (Adelman and Verkuyten Citation2020). Furthermore, existing research uses a variable-centred approach to assess between-individual difference in feelings and tolerance and how these are associated. The aim of the current study is to provide an incremental contribution to the literature by using a person-centred approach which offers a different way of thinking about the interplay of various feelings and evaluations (e.g. Osborne and Sibley Citation2017). This approach allows to examine whether there are distinct subgroups of individuals with different constellations of group-based feelings and (in)tolerance of specific practices. This provides a more detailed understanding of how particular forms of (in)tolerance simultaneously occur within individuals, and how these are combined with feelings towards Muslims as a group. We used data from a study among ethnic Dutch respondents, which allows us to examine whether, and how many, majority members have specific patterns of group-based feelings and (in)tolerance of practices. Furthermore, to validate the profiles’ distinctiveness, we examine whether the various subgroups of individuals are characterised by differences in authoritarian and conservative predispositions (Stenner Citation2005), as well as unconditional respect for persons (Lalljee, Laham, and Tam Citation2007). We focus on authoritarianism, status quo conservatism and unconditional respect because previous research has identified consistent links between these psychological constructs and acceptance or rejection of outgroups and their practices. However, they have not been examined simultaneously in relation to people’s evaluations of Muslim minorities and their practices. Additionally, we examine whether the subgroups of individuals differ in their feelings toward other minority groups and in their acceptance of other controversial practices (i.e. use of gender-neutral language).

Possible latent profiles

Social scientific research typically investigates associations between variables, such as between group-based feelings and the acceptance of specific practices. While these variable-centred analyses are extremely useful in their own right, a person-centred approach can make an additional contribution to social scientific research (Osborne and Sibley Citation2017), and has found to be useful in investigating attitudes toward minority outgroups (e.g. Adelman and Verkuyten Citation2020; Meeusen et al. Citation2018). In contrast to examining relations between variables, this approach seeks to identify unobserved subgroups of individuals who qualitatively differ in the particular ways in which they combine, for example, group-based feelings and the acceptance of practices. A shift to a person-centred approach is not simply a shift in methods but involves a different way of thinking about people’s attitudes, feelings and beliefs. A person-centred approach does not focus on differences between individuals but rather on how configurations of attitudes and feelings are organised within subgroups of individuals. For example, research on political tolerance of different groups and different practices demonstrates that individuals can not readily be placed on a positive–negative continuum but rather formed four latent classes of tolerance (McCutcheon Citation1985). In addition to subgroups of individuals who were consistently positive or consistently negative across practices and minority groups, there were also individuals who accepted some groups and some practices but rejected others (Adelman and Verkuyten Citation2020).

Thus, a person-centred approach allows to investigate whether feelings towards Muslims and the acceptance of a range of Muslim practices are combined in different ways within different subgroups of individuals, which is reflected in distinct latent profiles. In general, people can be positive or negative towards Muslims as a group, consistently accept or reject a range or practices, or accept some practices and reject others. Logically this suggests six possible subgroups () and there are reasons to assume that these are substantially meaningful subgroups of individuals that exist within the majority population, although some subgroups are more likely than others.

Table 1. Six possible latent profiles.

First and following the literature that links support for Muslim minority practices with group-based feelings, two subgroups of individuals are likely to exist. On the one hand, a subgroup of individuals with a generally positive orientation (‘positive’) that has positive feelings towards Muslims as a group and accept the right of Muslims to live the life that they want by practicing all aspects of their religion. On the other hand, it is likely that there is a subgroup of individuals with a generally negative orientation (‘negative’) that has negative feelings towards Muslims as a group and consistently reject all Muslim practices.

Two other likely subgroups consist of individuals that reject some or all Muslim minority practices without necessarily having negative feelings towards Muslims (Adelman and Verkuyten Citation2020). A third subgroup might thus comprise of individuals who do not dislike Muslims as a group but rather object toward all Muslim practices because these are considered to go against, for example, the majority’s ways of life and therefore imply large societal change (‘intolerant’). A fourth subgroup of individuals is likely to not display negative feelings towards the group per se but reject some Muslim practices and accept other practices (‘partly intolerant’). These individuals object to certain practices but accept other practices because they take the nature of the specific practices into consideration. For example, a particular practice might raise specific moral concerns and therefore be rejected, not only when practiced by Muslims but also by other religious groups (Hirsch, Verkuyten, and Yogeeswaran Citation2019; Sleijpen, Verkuyten, and Adelman Citation2020).

The remaining two possible subgroups consists of individuals who accept some or all of the Muslim practices while harbouring negative feelings towards Muslims as a group. Thus, a fifth possible subgroup could consists of individuals who are negative towards Muslims as a group, but accept all Muslim practices because, for example, they are strongly in favour of everyone having the freedom to practicing their own way of life (‘tolerant'; Mondak and Sanders Citation2003). However, some authors doubt the existence of such an absolutely tolerant group (Gibson Citation2005) and consider it more realistic that people accept only some practices of the group they harbour negative feelings towards (‘partly tolerant').

Validation of (in)tolerance profiles

Beyond identifying subgroups of individuals among the majority population, we examined whether these subgroups differ in a meaningful way on the key psychological correlates of authoritarian and conservative predispositions as well as the endorsement of unconditional respect for persons, and in their feelings towards other minority groups and the acceptance of other controversial, non-Muslim practices. This is important to examine as a matter of construct validity of the possible latent profiles and their substantial meaning (Osborne and Sibley Citation2017). If these profiles are meaningful beyond the Muslim practices used to identify the subgroups, they should relate to psychological constructs and attitudes toward other groups and practices in specific ways.

Authoritarian predisposition

There is a large literature that links the concept of authoritarianism to prejudice and intolerance toward minority groups. Following the original formulation of authoritarianism (Adorno et al. Citation1950) and its subsequent reconceptualisation (Altemeyer Citation1981), more recent conceptualisations are based on the notion of a tension that exists between the goals of personal autonomy and social conformity (Feldman Citation2003; Stenner Citation2005). Relating authoritarianism to Schwartz’s values of self-direction versus conformity, Feldman (Citation2003) shows that authoritarians are especially likely to prioritise conformity and obedience over self-direction and independence.

Authoritarians’ striving for uniformity and conformity typically implies that they try to minimise cultural diversity and maximise similarity in beliefs, norms and values. As a result, they tend to feel aversion toward groups that are dissimilar to them in norms and values and thereby threaten the normative order of society (Stenner Citation2005; Van Assche et al. Citation2019). Authoritarians reject diversity in general, and thus also oppose divergent practices that do not directly affect them personally. Research has shown that authoritarianism is associated with more negative attitudes towards Muslim minorities (Padovan and Alietti Citation2012), with opposition toward Muslim minority practices (e.g. the building of mosques in American cities; Feldman Citation2020), and with support of anti-Muslim policies (Dunwoody and McFarland Citation2017). Given that authoritarianism entails an emphasis on uniformity and conformity and, hence, an aversion to diversity of people and beliefs, individuals who display negative feelings towards Muslims and consistently show intolerance of Muslim minority practices (‘negative’) are likely to be characterised by relatively high authoritarianism. In contrast, those who display positive feelings towards Muslims and acceptance of some or all of Muslim minority practices (‘positive’, ‘partly intolerant’, ‘intolerant’, ‘partly tolerant’, and ‘tolerant’) are likely characterised by lower levels of authoritarianism.

Status quo conservatism

Whereas authoritarianism entails an underlying inclination to favour social conformity over individual autonomy and difference, status quo conservatism entails an ‘enduring inclination to favour stability and preservation of the status quo over social change’ (Stenner Citation2005, 86). Authoritarians value social uniformity and tend to favour normative conformity but are willing to gradually adopt new social norms as they evolve (Oyamot et al. Citation2017), whereas status quo conservatives favour social stability and have a general aversion to social change and the uncertainties that it entails. Research in different national contexts has demonstrated that authoritarianism and conservatism are distinct underlying predispositions that relate differently to various types of intolerance (Stenner Citation2005; Citation2009).

Conservatives do not want to move towards an uncertain future and therefore want to avoid social change whatever the direction of the change is. This understanding of conservatism has similarities with the notion of cultural inertia that is defined as the desire to avoid and resist any change (Zárate and Shaw Citation2010; Zárate et al. Citation2012). Change implies uncertainty and requires adapting to new situations which can produce resentment and negativity towards new developments and practices. One study found that the objection to Muslim minorities practices was associated with the endorsement of the value of traditionalism, which, just like status quo conservatism, reflects a preference to preserve the social world as it is (Van der Noll Citation2014).

People who score high on status quo conservatism are more likely to reject all Muslims practices as these differ from the majority’s way of life and might be perceived to indicate change. However, the rejection of these practices does not have to imply a dislike of Muslims as a group of people because for conservatives the issue is less about who is changing the status quo but rather whether in general the status quo is changed. Therefore, those who display intolerance towards all Muslim practices (‘negative’ and ‘intolerant’) are likely to be characterised by relatively high status quo conservatism. In contrast, those who differentiate between practices by accepting some and rejecting others (‘partly intolerant’ and ‘partly tolerant’) and those who accept all practices (‘positive’ and ‘tolerant’) are likely to be characterised by lower levels of status quo conservatism.

Unconditional respect

Unconditional respect for persons forms the cornerstone of Kant’s moral philosophy and entails the most fundamental form of respect for others, simply as a function of them being human beings (Lalljee, Laham, and Tam Citation2007; Lalljee et al. Citation2009). It is a general orientation towards all people having intrinsic and equal moral worth and involves the recognition of everyone’s dignity and integrity. Unconditional respect for persons has been found to be negatively associated with right-wing authoritarianism (Lalljee, Laham, and Tam Citation2007) and can be expected to be associated with more positive attitudes towards minority groups.

Unconditional respect primary refers to others as human beings and is likely to include acceptance of others’ practices. Research in different European countries has demonstrated that respect towards members of other groups is associated with tolerance for out-groups’ way of life (e.g. Hjerm et al. Citation2019; Simon et al. Citation2019). However, being respectful towards a group of people does not necessary mean that one will accept all their practices, especially if these are construed as being disrespectful towards the dignity and integrity of others. An example is the refusal of some Muslims to shake hands with people of the opposite gender, which has been debated in Dutch society as a form of disrespect for the personhood of others (Gieling, Thijs, and Verkuyten Citation2010). Thus, those who are positive towards Muslims and accept all or some of the practices (‘positive’ and ‘partly intolerant’) are likely to score higher on unconditional respect. In contrast, those who are negative towards Muslims or reject some or all Muslim practices (‘negative’, ‘intolerant’, ‘partly tolerant’, ‘tolerant’) are likely to score lower on unconditional respect.

Other minority groups and other practices

As a matter of construct validity, we further examine how different subgroups of individuals feel about other minority groups (e.g. refugees, German and Polish people in the Netherlands) and evaluate other controversial practices (e.g. related to homosexuality and gender neutrality). If the identified profiles are meaningful beyond Muslims and their practices, then people who belong to these profiles should react to other minority groups and other controversial practices in specific ways.

The subgroup of individuals that displays positive feelings towards Muslims and tolerance of all or some Muslim practices (‘positive’ and ‘partly intolerant’) is likely to be characterised by a strong endorsement of unconditional respect and low scores on authoritarianism and conservatism. Therefore, these subgroups should also have positive feelings towards other minority groups and display tolerance of other practices. In contrast, the subgroup of individuals that displays anti-Muslim feelings and intolerance of all Muslim practices (‘negative') can be expected to also harbour negative feelings towards other minority groups and to display intolerance of other controversial practices. The reason is that this subgroup of individuals is expected to be characterised by a relatively strong authoritarian predisposition which has been found to be associated with prejudicial attitudes toward various minority groups (i.e. Duckitt and Sibley Citation2007), and intolerance of normatively dissenting practices, such as gay marriage and new gender norms (e.g. Oyamot et al. Citation2017).

Further, we have argued that the subgroup of individuals that is intolerant of all Muslim practices without harbouring negative feelings towards Muslims as a group (‘intolerant’), is likely to endorse status quo conservatism. They object to practices that imply social change rather than having negative feelings towards groups of people as such. Therefore, these individuals might also be intolerant of homosexual and gender-neutral practices that involve societal change, but without necessarily displaying negative feelings towards other minority groups.

To summarise

Using latent profile analysis, we examine the different ways in which subgroups of majority members combine their general feelings towards Muslims with their acceptance of a range of Muslim practices that are debated in Dutch society. Specifically we examine whether six theoretically and logically possible configurations of how general feelings and the acceptance of practices are organised within individuals receive empirical support: positive, negative, intolerant, partly intolerant, tolerant, and partly tolerant (see ). To establish construct validity of these profiles, we examine if these subgroups differ in a meaningful way in their authoritarian and conservative predispositions, endorsement of unconditional respect for persons, positive feelings toward other out-groups, and the acceptance of other controversial practices.

We used data from a large sample of Dutch majority participants. In the Netherlands, Islam is the second largest religion with Muslims – mainly originating from Turkey and Morocco – comprising around 5% of the population (Schmeets Citation2019; Huijnik Citation2018). Identification with Islam among Muslims continues to be strong, an increasing number of Islamic organisations and schools have been founded over the years, and a growing number of Muslims engage in religious practices such as visiting a mosque and wearing a headscarf (Huijnik Citation2018). As in other Western countries, the Dutch public tends to perceive Muslims as the typical ‘other’ with goes together with relatively strong anti-Muslim sentiments (Sniderman and Hagendoorn Citation2007)

Method

Data and sample

Data was collected in February 2019 by a survey company which maintains a representative panel of adult DutchFootnote2 majority members. Panel members were sampled to match the population of the Netherlands in terms of age, gender, education, and region, and 831 non-Muslim respondents completed the anonymous questionnaire online. Thirteen respondents who did not reveal their religiosity were excluded from the regression analysis. The participants were between 18 and 88 years old (M = 54.8, SD = 16.23, ), and 51% of the sample was female.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of central variables used in the study.

Measures

Feelings towards Muslims. Respondents were presented a ‘feeling thermometer’ to indicate on an 11-point scale how warm or cold they felt towards the group of Muslims in the Netherlands. For the ease of interpretation, the variable was recoded to range from −5 to 5. Higher scores reflect more warm feelings towards Muslims, zero indicate neutral feelings, and lower scores reflect more cold feelings.

Tolerance of Muslims’ practices. Respondents were presented with a set of seven practices that were taken from previous research (Adelman and Verkuyten Citation2020) and that relate to issues that are or have been debated in the Netherlands: ‘Immigrants walking on the street wearing veils’, ‘The building of mosques in the Netherlands’, ‘The ritual slaughtering of animals’, ‘The establishment of Islamic primary schools’, ‘Replacing the second day of Pentecost by the Islamic Sugar festival as a national holiday’, ‘The refusal of some Muslims to shake hands with people of the opposite sex’, and ‘The founding of political parties that are inspired by Islam’. Participants indicated on a 7-point scale to what extent these practices should (1) ‘certainly not be tolerated’, or (7) ‘certainly be tolerated’. The scales were recoded to range from −3 to 3, with higher values indicating higher tolerance.

Authoritarian predisposition was measured with an extended version of the validated ‘child-rearing preference’ scale which makes no reference to any social groups or political actors. This measure was designed to tap into the underlying disposition by assessing a relative priority and therefore creates a trade-off between stimulating social conformity and obedience versus self-direction and autonomy in socialising children (Feldman Citation2003; Stenner Citation2005). Respondents were presented with four pairs of qualities children could be taught (for example, ‘obeying parents’ versus ‘making one’s own choices’). For each of the pairs, respondents were asked which one they would consider to be more important, and subsequently, to indicate how much more important they found this quality using a 3-point scale (slightly more important, more important, or much more important). The answers to these two questions for a given pair of qualities were recoded to a six-point scale so that a higher score indicates stronger authoritarian predisposition. The scores on the four items were averaged to create a scale (ρ = .72).

Status quo conservatism. In order to have a similar relative measure as for authoritarianism we designed four items that introduced a trade-off between a focus on the importance and benefits of social change in general versus a positive emphasis on stability (Stenner Citation2005). We again made no references to any social groups or political actors. Each item represented a pair of opposing statements placed on the opposite side of the 7-point scale continuum; one side indicated resistance to change (status quo conservatism) and the other side indicated being in favour of change (for example, ‘Traditional ways have to be cherished and preserved’ versus ‘You have to change and adjust habits to the new time’) The items were averaged to create a scale (ρ = .62) and a higher score indicates higher status quo conservatism.

Unconditional respect for persons. Unconditional respect was measured by six items (7-point scales) taken from Lalljee and colleagues (Citation2007; for example, ‘Also people with objectionable ideas should be respected as persons'). The six items were averaged to form a scale (ρ = .69), and a higher score indicates higher unconditional respect.

Feelings towards other minority groups. Respondents indicated their general feelings towards Germans, Poles and refugees, as three other minority groups living in the Netherlands, on the same feeling thermometer scales.

Tolerance of gender-neutral practices. Using the same scale as for tolerance of Muslims’ practices, respondents were asked whether the following practices should be tolerated: ‘Installing gender-neutral toilets in public buildings’, and ‘Replacing words such as ‘manpower’ and ‘ladies and gentlemen’ with gender-neutral names such as ‘human-power’ and ‘travelers’. The Netherlands saw a heated public debate about these practices in the year in which the data were collected, for example when the Dutch national railway company started addressing passengers with ‘dear travelers’ instead of ‘dear ladies and gentlemen’ in their announcements.

Tolerance of homosexual practice. Tolerance of homosexual practice was measured on the same scale by asking whether ‘Homosexual men kissing each other in public’ (Kuyper Citation2016) should be tolerated. In the Netherlands, people are relatively tolerant towards homosexuality but many object to public expression of this sexual orientation and in particular to men kissing in public (Keuzenkamp and Kuyper Citation2013).

Control variables. Four control variables were used in the analyses. In addition to age (continuous variable) and gender (0 = men, 1 = women), participants indicated the highest level of completed education using a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (no/only primary school) to 7 (master degree at (applied) university level). Similar to other research in the Netherlands (e.g. Van de Werfhorst and Van Tubergen Citation2007), education was treated as a continuous variable in the analysis. In addition to standard individual-level control variables, we controlled for importance of religiosity because religious people may be more positive or more negative towards other religions. Religiosity was measured by asking respondent to indicate on a 7-point scale to what extent their faith was important to them, ranging from 1 (not at all important) to 7 (extremely important). In addition, respondents were offered not to reveal their religiosity by indicating ‘I do not want to say’. Since the variable was skewed (almost half of respondents indicated that they do not find religion important at all), it was recoded to a dichotomous variable (0 = important, and 1 = not at all important).

Analysis

We used latent profile analysis (LPA) to identify the optimal number of distinctive subgroups of individuals. The LPA is a model-based technique that offers more rigorous criteria for choosing the optimal number of profiles compared to traditional clustering techniques that also have been criticised as being too sensitive to the clustering algorithm and measurement scales, and as relying on rigid assumptions that do not always hold with real-life data (Vermunt and Magidson Citation2002). In addition, in LPA various models can be specified in terms of how variances and covariances are estimated. All of our solutions were fitted under the model with class-invariant parametrisation. In this model, the variances of the items are estimated to be equal across profiles and the covariances are constrained to zero. Therefore, the model considers the mean vectors for each profile. The choice of class-invariant parametrisation was based on two considerations. First, we were interested in the average levels of the measures in each profile and not in the extent to which these measures vary or how they relate to each other within or across the profiles. Second, class-invariant parametrisation yields the most parsimonious model. In order to avoid convergence of the likelihood function to local instead of global maxima solutions (Nylund-Gibson and Choi Citation2018), 5000 sets of random starts and 500 final stage optimisations were used.

LPA provides a series of fit indices to compare and identify the appropriate number of profiles. The Bayesian information criteria (BIC) and the Akaike information criteria (AIC) indicate how well a model with the selected number of profiles fits the data, with the lowest numbers indicating the best fit. Entropy scores indicate the precision with which respondents are classified into the profiles, and high entropy scores (> .8) indicate good precision of the classification (Nylund-Gibson and Choi Citation2018). Lastly, to determine the optimal number of profiles it is important to consider the substantive meaning and theoretical interpretability of the profiles. The number of participants within each profile should not be too small and the profiles should conform with theoretical understandings.

In the second part of the analysis, multinomial logistic regression analysis was used for the construct validity analysis. We predicted the likelihood of belonging to one of the identified subgroups as a function of authoritarianism, status quo conservatism, unconditional respect, and the control variables. In the last step, we examined whether the identified subgroups differed in their feelings towards other immigrant groups and their tolerance of other controversial practices. For this, we used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and pairwise t-test with Bonferroni correction to control for Type I error rate across multiple comparisons.

Results

Descriptive findings

shows the descriptive findings.Footnote3 On average, respondents indicated that Muslim practices should not be tolerated as the means of all practices were significantly below the midpoint of the scale, ps < .001. Further, respondents had negative feelings toward Muslims as the mean value also was significantly below the midpoint, t (830) = −4.46, p < .001. Unconditional respect was negatively correlated with authoritarianism and status quo conservatism, while authoritarianism was positively but not strongly associated with status quo conservatism, supporting the notion that both constructs are relatively independent (Stenner Citation2005).

Latent profile analysis

shows the findings for different profile estimates up to seven profiles. The fit statistics kept on improving with the addition of latent profiles, and the entropy values are high for all estimated models which suggests that the decision of how many profiles to retain should mainly focus on interpretability and the size of the profiles (Nylund-Gibson and Choi Citation2018; Marsh et al. Citation2009).

Table 3. Latent profile analysis: model fit statistics and profile membership distribution.

The inspection of the interpretability and size of profiles in all estimated solutions revealed that the solution with 5 profiles is the most appropriate one. Models with more than 5 profiles did not reveal additional subgroups that were substantively different from the first five (see Figure A1 in supplementary materials), and, importantly, the additional profiles had a very small sample size (for example, three of the profiles of the six-profile solution had less than 10% of classified individuals each). The 5 profile solution revealed profiles that were quantitatively different (see Table A1 in supplementary materials) and the closest to the theoretically discussed possibilities.

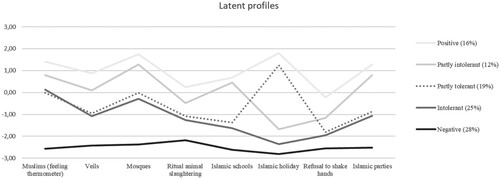

displays the mean scores on the feeling thermometer and Muslim practices for each of the five subgroups with their respective labels. The first subgroup is characterised by general positive feelings towards the group of Muslims and tolerance of almost all of the Muslim practices (‘positive'; 16% of respondents). In contrast, the second subgroup is characterised by negative feelings towards Muslims as a group and intolerance of all practices (‘negative’; 28%). These two subgroups of individuals displayed consistent positive or negative reactions towards Muslims and Muslim practices, but this was not the case for the three other subgroups that comprised more than half of the sample. The third subgroup consists of individuals that, on average, reported neutral to slightly positive feelings towards Muslims, but nevertheless indicated that none of the seven Muslim practices should be tolerated (‘intolerant’; 25%). The fourth subgroup was characterised by a similar pattern of responses, except that they accepted an Islamic holiday replacing a Christian holiday (‘partly tolerant'; 19%). Finally, the fifth subgroup was characterised by positive feelings towards Muslims, and differential intolerance of the practices (‘partly intolerant'; 12%). The latter two subgroups tolerated some practices (e.g. mosques, Islamic holidays) but not others (e.g. refusal to shake hands), which suggests that for them, the nature of the practices matters. These five profiles are largely in line with what we discussed as theoretical possibilities. Although theoretically possible, a subgroup that combines negative feelings towards the group with acceptance of all practices was not found. Thus, our findings provide no empirical support for tolerance in which people are willing to put up with practices and believes of groups they dislike, which is typical for political tolerance (GibsonCitation2005).

Validation of (in)tolerance profiles

We further examined the meaningfulness of the five profiles identified by investigating how they differ on key variables as a matter of construct validity. presents the results of the comparisons in which the partly intolerant (Model A), and subsequently the intolerant subgroup (Model B) were the reference categories. The use of these two reference categories allows us to examine in which ways the various subgroups differ from the intolerant ones. Overall, the partial intolerant group and the intolerant group appear to be distinct from the positive, the negative, and partly tolerant group, and also from each other.

Table 4. Results of multinomial logistic regression analysis (standardised coefficients, N = 818).

First, individuals within the positive subgroup were more likely to endorse unconditional respect compared to the partly intolerant individuals (B = 0.64, SE = 0.15, p < .001) and intolerant ones (B = 0.35, SE = 0.16, p < .05). Further, individuals in the positive subgroup were more likely to indicate that religion is not important for them compared to those in the partly intolerant group (B = 1.01, SE = 0.29, p < .001), and were less authoritarian (B = −0.27, SE = 14, p < .05), less conservative (B = −0.52, SE = 0.14, p < .001), and more educated (B = 0.57, SE = 0.15, p < .001) compared to the intolerant subgroup. This pattern of findings supports the reasoning that the positive profile is most clearly characterised by the endorsement of unconditional respect for persons.

Second, unconditional respect for persons was less likely for individuals belonging to the negative subgroup compared to the intolerant (B = −0.41, SE = 0.11, p < .001) and partial intolerant (B = −0.70, SE = 0.15, p < .001) groups. In contrast, individuals in the negative group were more likely to endorse authoritarian values, compared to both the intolerant (B = 0.46, SE = 0.12, p < .01) and partly intolerant (B = 0.43, SE = 0.15, p < .001) groups. Further, individuals in the negative subgroup were more conservative (B = 0.43, SE = 0.14, p < .01), indicated that religion is not important (B = 0.93, SE = 0.28, p < .001), and were less educated (B = −0.56, SE = 0.15, p < .001) compared to the partly intolerant group, but not in comparison to the intolerant group. This pattern of findings supports the reasoning that especially a strong authoritarian predisposition is a distinctive characteristic of the negative subgroup of individuals.

Third, individuals in the intolerant subgroup were more likely to have lower levels of formal education (B = −0.37, SE = 0.15, p < .05), to be older (B = 0.40, SE = 0.13, p < .05), and to indicated that religion is not important compared to individuals in the partly intolerant group. In addition, individuals belonging to the intolerant, compared to the partial intolerant group, were less likely to endorse unconditional respect (B = −30, SE = 0.15, p < .05) and more likely to be conservative (B = 0.34, SE = 0.14, p < .05). This pattern of findings suggests that the intolerant group of individuals is characterised by status quo conservatism, without the strong authoritarian predisposition that characterises the negative subgroup.

Fourth, those who belonged to the partly tolerant group, rather than the partly intolerant subgroup, were more likely to indicate that religion is not important (B = 0.75, SE = 0.28, p < .01). Further, the partly intolerant were less conservative (B = −0.41, SE = 0.12, p < .001) than the intolerant subgroup. Being less religious and having a less conservative orientation seems to make the partly tolerant subgroup accept Islamic Breaking the Fast as a national holiday instead of the second day of Pentecost.

Overall, the strong endorsement of unconditional respect of the positive and the partly intolerant subgroups, the authoritarian predisposition of the negative subgroup and the conservatism of the intolerant subgroup, support our expectations that the subgroups differ in a meaningful way.

Out-group feelings and tolerance of other practices

presents the mean scores of feelings towards other minority groups and tolerance of other controversial practices of the five subgroups as an additional construct validity analysis.

Table 5. Between-profile comparisons of feelings towards other groups and tolerance of controversial practices (mean values).

One-way ANOVAs revealed that the positive subgroup was more positive towards refugees and Poles than the negative subgroup, and more positive towards refugees than partly tolerant and intolerant subgroups (see the last two rows of ). Furthermore, they were more accepting of homosexual men kissing in public and gender neutral practices. This pattern of results is similar to the one the positive subgroup displayed towards Muslims and their practices, and corresponds with the strong endorsement of unconditional respect for persons, and low authoritarian and conservative predispositions among this subgroup.

Individuals in the negative subgroup reported the most negative feelings towards refugees and Poles. In addition, they were significantly less tolerant of homosexual men kissing in public and gender-neutral practices than the other subgroups. This pattern of responses is also similar as their responses towards Muslims and their practices, and in line with the relative strong authoritarian and conservative predisposition, and low endorsement of unconditional respect of this subgroup.

The partly intolerant and the intolerant subgroup were positive towards other minorities, and accepting of homosexual men kissing each other. However, the intolerant subgroup was less accepting of gender neutrality than the partly intolerant subgroup. This pattern of responses is also similar as their responses towards Muslims and their practices, and in line with the relatively stronger endorsement of unconditional respect of the partly intolerant subgroup, and the more conservative predisposition of the intolerant subgroup.

Overall, the generalised acceptance of the positive subgroup, the generalised rejection of the negative subgroup, and the stronger acceptance of other controversial practices of the partly intolerant subgroup, support our expectations that individuals in the identified profiles respond in a similar way to Muslims and other minority groups.

Discussion

While some researchers argue that anti-Muslim feelings underlie the rejection of Muslim practices (e.g. Saroglou et al. Citation2009), others claim that it is more complex and that also people with positive feelings toward Muslims can reject certain practices, and people with negative feelings towards Muslims can accept specific practices (e.g. Van der Noll Citation2014). We aimed to extend theory and research on anti-Muslim sentiments by examining the ways in which group-based feelings towards Muslims and (in)tolerance of a range Muslim practices are organised within individuals. We provide an incremental contribution to the literature by using a person-centred approach and identifying in a national sample five distinct profiles that are validated across various correlates (Adelman and Verkuyten Citation2020).

First, we found two opposite subgroups of individuals: a positive subgroup (16%) with a generally positive orientation towards Muslims and their practices, and a negative subgroup (28%) with a generally negative orientation towards Muslims and their practices. These subgroups are in line with the assumption that group-based feelings underlie the (in)tolerance of Muslim practices (Saroglou et al. Citation2009). However, the feelings and (in)tolerance of both subgroups appear not to be specific toward Muslims but rather reflect a more general positive or negative orientation towards minority groups (Polish immigrants, refugees) and controversial minority practices related to gender and sexuality.

For the positive subgroup the general orientation seems to involve a relatively strong endorsement of unconditional respect for persons which is in line with research that shows that equal respect is an important ingredient for accepting controversial practices (Simon et al. Citation2019), and that respect-based tolerance is associated with a more positive attitude toward immigrants, homosexuals and women (Hjerm et al. Citation2019). The negative subgroup is characterised by a relatively strong authoritarian predisposition. Authoritarians value social conformity and tend to reject anything that goes against conventions and common norms and values (Stenner Citation2005; Van Assche et al. Citation2019) resulting in negative feelings towards different minority groups and the rejection of all controversial practices.

Less than half (46%) of the national majority sample belonged to the positive or negative subgroups which indicates that a small majority showed more complex responses in which their feeling towards Muslims and the acceptance of Muslim practices did not fully correspond. Two of these subgroups combined positive feelings towards Muslims with rejection of the practices. The intolerant subgroup (25%) consisted of individuals who reported neutral feelings towards Muslims but were intolerant of all Muslim practices. And individuals in the partly intolerant subgroup (12%) reported positive feelings towards Muslims but were intolerant of some Muslim practices. These findings demonstrate that people can be intolerant of minority practices without necessarily having negative feelings toward Muslims as a group (Bilodeau et al. Citation2018). The two intolerant subgroups appear to represent relatively large sections of the public containing more than a third of the respondents. This indicates that researchers should be careful in assuming that intolerance of Muslim practices is mainly motivated by anti-Muslim feelings.

Rather, the intolerant subgroup was characterised by a relatively strong conservative predisposition in which social change in and of itself is rejected and resisted. These individuals were less authoritarian than the negative subgroup and did not harbour clear negative feelings toward Muslims as a group, but were intolerant of all Muslim practices that typically imply societal change. They were also not negative toward other minority groups, but they did reject societal changes related to practicing gender neutrality. This pattern of findings suggests that this subgroup of individuals prefers stability and continuity over change and uncertainty. It indicates that intolerance of Muslim practices can stem from resistance to change in and of itself, rather than from anti-Muslim feelings. This relates to research on cultural inertia which demonstrates that the desire to avoid cultural change per se plays a role in negative reactions toward minority groups (Zárate et al. Citation2012).

The presence of the partly intolerant subgroup supports the proposition that intolerance can be based on an objection to specific Muslim practice rather than negative feelings toward the group of people (Sniderman and Hagendoorn Citation2007; Van der Noll Citation2014). This subgroup of individuals did not report anti-Muslim feelings and differentiated between Muslim practices by accepting some (i.e. building of Mosques) and rejecting others (e.g. refusal to shake hand with opposite gender). They also were not negative toward other minority groups and accepted gender-neutral adaptations. Compared to the intolerant subgroup, the partial intolerant group was characterised by a less conservative predisposition and a stronger endorsement of unconditional respect. The finding that this subgroup was negative about Muslims refusing to shake hands with people of the opposite gender also suggests that the endorsement of unconditional respect for persons can also lead to intolerance of particular minority practices. In Western societies, such a refusal is typically construed and discussed as being disrespectful towards others and therefore as something that should not be tolerated (Gieling, Thijs, and Verkuyten Citation2010). People tend to be intolerant of morally objectionable practices, independently of whether one likes or dislikes the group (Hirsch, Verkuyten, and Yogeeswaran Citation2019).

Whereas combining positive feelings towards the group with rejection of some, or all, practices was relatively common among majority members, combining negative feelings with acceptance of some, or all, practices appears to be more exceptional. The partly tolerant subgroup (19%) consisted of individuals who did not harbour positive feelings towards the group, but accepted Islamic Sugar festival as an alternative national holiday. This subgroup was relatively less religious and also less conservative, which seems to make these individuals willing to accept an Islamic festivity as an alternative national holiday.

Limitations

Despite its important and novel contributions, our study has some limitations that provide directions for future research, and we like to briefly mention two of these. The findings of latent profile analysis are dependent on the number and type of practices that are considered. Therefore, different subgroups might emerge if other practices would be considered, such as practices that involve more demanding issues (e.g. gender segregation). Future research considering a broader range of Muslim practices could examine the robustness of the current findings. Furthermore, future research could also examine the acceptance of similar practices of different minority groups and whether people use a double standard in accepting the same practice for one group but not for another (Sleijpen, Verkuyten, and Adelman Citation2020).

Our results provide evidence that the rejection of Muslim practices without harbouring negative feelings can stem from a conservative predisposition against change in and of itself. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that such a consistent rejection of the practices is (partly) the result of an unwillingness to express anti-Muslim feelings due to social desirability concerns. Yet, the questionnaire data used in the current study were collected via an online panel and the participants in these panels know that their answers will be completely anonymous. The provision of complete anonymity minimise social desirability pressures on self-report measures because there is no incentive to present oneself in socially desirable ways (Stark et al. Citation2019).

Conclusion

This study advances the literature on anti-Muslim sentiments by considering a range of Muslim practices and using a person-centred approach. Our findings provide greater nuance by identifying more complex constellations of people’s feelings toward Muslim as a group and their acceptance of a range of practices. For some individuals, their (in)tolerance of Muslim practices corresponds with their group-based feelings, but for others it does not. This indicates that an interpretation in terms of generalised prejudice is limited as it ignores that people can reject some practices and accept others. Rejection of a particular practice (e.g. refusal to shake hands) cannot simply be taken to indicate anti-Muslim feelings but might also express conservative predispositions and even the unconditional respect of persons.

In light of contentious societal debates about the acceptance of Muslim minorities in Western societies, it is critical to consider the different ways in which various subgroups of majority members think about this and to develop an accurate understanding or people’s feelings and attitudes. Many majority members do not have a consistently positive or negative orientation but rather might be struggling with their group-based feelings and how they should respond to specific Muslim practices. We showed that a latent profile analysis makes it possible to identify subgroups of individuals who differ in how configurations of feelings towards Muslims and their acceptance of a range of Muslim practices are organised within individuals (Adelman and Verkuyten Citation2020). These subgroups cannot be placed on a unidimensional attitude continuum but rather form categories of people who differ in understandable ways on their authoritarian and conservative predispositions, the endorsement of unconditional respect for others, and their feelings towards other minority groups and acceptance non-Muslim practices.

We identified five profiles that make theoretical sense which suggests that our findings provide a fairly accurate and meaningful representation of the types of profiles that are likely to exist in relation to majority members reactions toward Muslim minorities. In contrast to the variable-centred approach we focused on the different constellations of general feelings and tolerance of specific practices within individuals and therefore provide a more complete and integrated description of the relevant distinctions. Such a description is important for applied reasons because it makes a more targeted intervention possible. Interventions based on variable-centred analyses often lead to thinking about improving a particular attitude but without taking into consideration what this might do to other attitudes. Knowing that more than half of the public is not consistently negative or positive towards Muslim minorities implies the possibility of more targeted interventions that focus on the various reasons that people have for tolerating some practices but not others. For example, interventions targeting individuals who are concerned about societal changes in general could emphasise positive aspects of change, but these individuals might also perceive Muslim practices as being disrespectful which requires an additional focus on the societal importance of recognising the personhood of everyone. An approach that takes the constellation of feelings and beliefs into account can contribute to finding productive ways for reducing negative attitudes and behaviours towards Muslim minorities in western societies.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 By using the term ‘Muslim minority practice’ we are not implying that these are typical for Muslims but rather indicating how these practices are often perceived in Western societies.

2 This is based on the definition of the Central Bureau for Statistics in the Netherlands (CBS Citation2016) that considers everyone with both parents born in the Netherlands as belonging to the Dutch majority group.

3 The data and analytic scripts reproducing our findings can be found at https://osf.io/d8qyj/.

References

- Adelman, L. Y., and M. Verkuyten. 2020. “Prejudices and the Acceptance of Minority Practices: A Person-Centered Approach.” Social Psychology 51 (1): 1–16. doi: 10.1027/1864-9335/a000380

- Adorno, T., E. FrenkeI-Brunswik, D. Levinson, and R. N. Sanford. 1950. The Authoritarian Personality. New York: Harper.

- Altemeyer, B. 1981. Right-wing Authoritarianism. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press.

- Bilodeau, A., L. Turgeon, S. White, and A. Henderson. 2018. “Strange Bedfellows? Attitudes Toward Minority and Majority Religious Symbols in the Public Sphere.” Politics and Religion 11 (2): 309–333. doi: 10.1017/S1755048317000748

- Blinder, S., R. Ford, and E. Ivarsflaten. 2019. “Discrimination, Antiprejudice Norms, and Public Support for Multicultural Policies in Europe: The Case of Religious Schools.” Comparative Political Studies 52 (8): 1232–1255. doi: 10.1177/0010414019830728

- CBS. 2016. Jaarrapport Integratie 2016 [Annual Integration Report 2016]. The Hague: CBS. https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/publicatie/2016/47/jaarrapport-integratie-2016.

- Duckitt, J., and C. G. Sibley. 2007. “Right-wing Authoritarianism, Social Dominance Orientation and the Dimensions of Generalized Prejudice.” European Journal of Personality 21 (2): 113–130. doi: 10.1002/per.614

- Dunwoody, P. T., and S. G. McFarland. 2017. “Support for Anti-Muslim Policies: The Role of Political Traits and Threat Perception.” Political Psychology 39 (1): 89–106. doi: 10.1111/pops.12405

- Feldman, S. 2003. “Enforcing Social Conformity: A Theory of Authoritarianism.” Political Psychology 24 (1): 41–74. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00316

- Feldman, S. 2020. “Authoritarianism, Threat and Intolerance.” In At the Forefront of Political Psychology: Essays in Honor of John L. Sullivan, edited by E. Borgida, C. Federico, and J. Miller, 35–54. New York: Routledge.

- Gibson, J. L. 2005. “On the Nature of Tolerance: Dichotomous or Continuous?” Political Behavior 27 (4): 313–323. doi: 10.1007/s11109-005-3764-3

- Gieling, M., J. Thijs, and M. Verkuyten. 2010. “Tolerance of Practices by Muslim Actors: An Integrative Social-Developmental Perspective.” Child Development 81 (5): 1384–1399. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01480.x

- Haddad, Y. Y., and J. I. Smith. 2001. Muslim Minorities in the West: Visible and Invisible. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press.

- Helbling, M. 2012. “Islamophobia in the West: An Introduction.” In Islamophobia in the West. Measuring and Explaining Individual Attitudes, edited by M. Helbling, 1–18. London: Routledge.

- Helbling, M. 2014. “Opposing Muslims and the Muslim Headscarf in Western Europe.” European Sociological Review 30 (2): 242–257. doi: 10.1093/esr/jct038

- Helbling, M., and R. Traunmüller. 2018. “What is Islamophobia? Disentangling Citizens’ Feelings Toward Ethnicity, Religion and Religiosity Using a Survey Experiment.” British Journal of Political Science, 1–18. doi:10.1017/S0007123418000054.

- Hirsch, M., M. Verkuyten, and K. Yogeeswaran. 2019. “To Accept or Not to Accept: Level of Moral Concern Impacts on Tolerance of Muslim Minority Practices.” British Journal of Social Psychology 58: 196–210. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12284

- Hjerm, M., M. A. Eger, A. Bohman, and F. F. Connolly. 2019. “A New Approach to the Study of Tolerance: Conceptualizing and Measuring Acceptance, Respect, and Appreciation of Difference.” Social Indicators Research 147: 897–919. doi: 10.1007/s11205-019-02176-y

- Huijnik, W. 2018. De religieuze beleving van moslims in Nederland: Diversiteit en verandering in beeld [The Religious Experience of Muslims in the Netherlands]. Den Haag: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau. https://www.scp.nl/publicaties/publicaties/2018/06/07/de-religieuze-beleving-van-moslims-in-nederland.

- Hurwitz, J., and J. J. Mondak. 2002. “Democratic Principles, Discrimination and Political Intolerance.” British Journal of Political Science 32 (1): 93–118. doi: 10.1017/S0007123402000042

- Keuzenkamp, S., and S. Kuyper. 2013. Acceptance of Lesbian, gay, Bisexual and Transgender Individuals in the Netherlands 2013. The Hague: The Netherlands Institute for Social Research. https://www.tgns.ch/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/PDF-Acceptance- … .pdf.

- Kuyper, L. 2016. LHBT-monitor 2016: Opvattingen over en ervaringen van lesbische, homosexuale, bisexuale en transgender personen [LGBT-Monitor 2016: Attitudes About and Experiences of Lesbian, gay, Bisexual and Transgender Persons]. Den Haag: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau. https://www.staatvanutrecht.nl/sites/www.staatvanutrecht.nl/files/rapporten/SCP_2016_LHBT_monitor_2016.pdf.

- Lalljee, M., S. Laham, and T. Tam. 2007. “Unconditional Respect for Persons: A Social Psychological Analysis.” Gruppendynamik und Organisationsberatung [Group Dynamics and Organisation Consulting] 38: 451–464.

- Lalljee, M., T. Tam, M. Hewstone, S. Laham, and J. Lee. 2009. “Unconditional Respect for Persons and the Prediction of Intergroup Action Tendencies.” European Journal of Social Psychology 39 (5): 666–683. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.564

- Marsh, H., O. Ludtke, U. Trautwein, and A. Morin. 2009. “Classical Latent Profile Analysis of Academic Self-Concept Dimensions: Synergy of Person- and Variable-Centered Approaches to Theoretical Models of Self-Concept.” Structural Equation Modeling 16 (2): 191–225. doi: 10.1080/10705510902751010

- McCutcheon, A. L. 1985. “A Latent Class Analysis of Tolerance for Nonconformity in the American Public.” Public Opinion Quarterly 49 (4): 474–488. doi: 10.1086/268945

- Meeusen, C., B. Meuleman, K. Abts, and R. Bergh. 2018. “Comparing a Variable-Centered and a Person-Centered Approach to the Structure of Prejudice.” Social Psychological and Personality Science 9 (6): 645–655. doi: 10.1177/1948550617720273

- Mondak, J. J., and M. S. Sanders. 2003. “Tolerance and Intolerance, 1976–1998.” American Journal of Political Science 47 (3): 492–502. doi: 10.1111/1540-5907.00035

- Nylund-Gibson, K., and A. Y. Choi. 2018. “Ten Frequently Asked Questions About Latent Class Analysis.” Translational Issues in Psychological Science 4 (4): 440–461. doi: 10.1037/tps0000176

- Osborne, D., and C. G. Sibley. 2017. “Identifying “Types” of Ideologies and Intergroup Biases: Advancing a Person-Centred Approach to Social Psychology.” European Review of Social Psychology 28 (1): 288–332. doi: 10.1080/10463283.2017.1379265

- Oyamot, C. M., M. S. Jackson, E. L. Fisher, G. Deason, and E. Borgida. 2017. “Social Norms and Egalitarian Values Mitigate Authoritarian Intolerance Toward Sexual Minorities.” Political Psychology 38 (5): 777–794. doi: 10.1111/pops.12360

- Padovan, D., and A. Alietti. 2012. “The Racialization of Public Discourse: Antisemitism and Islamophobia in Italian Society.” European Societies 14 (2): 186–202. doi: 10.1080/14616696.2012.676456

- Saroglou, V., B. Lamkaddem, M. Van Pachterbeke, and C. Buxant. 2009. “Host Society’s Dislike of the Islamic Veil: The Role of Subtle Prejudice, Values, and Religion.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 33 (5): 419–428. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2009.02.005

- Schmeets, H. 2019. Religie en sociele cohesive [Religion and Social Cohesion]. Den Haag: Centra Bureau voor de Statistiek. https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/achtergrond/2019/28/religie-en-sociale-cohesie.

- Simon, B., S. Eschert, C. D. Schaefer, K. M. Reininger, S. Zitzmann, and H. J. Smith. 2019. “Disapproved, But Tolerated: The Role of Respect in Outgroup Tolerance.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 45 (3): 406–415. doi: 10.1177/0146167218787810

- Sleijpen, S., M. Verkuyten, and L. Adelman. 2020. “Accepting Muslim Minority Practices: A Case of Discriminatory or Normative Intolerance?” Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology 30 (4): 405–418. doi: 10.1002/casp.2450

- Sniderman, P. M., and A. Hagendoorn. 2007. When Ways of Life Collide: Multiculturalism and its Discontents in the Netherlands. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Stark, T. H., F. M. van Maaren, J. A. Krosnick, and G. Sood. 2019. “The Impact of Social Desirability Pressures on Whites’ Endorsement of Racial Stereotypes: A Comparison Between Oral and ACASI Reports in a National Survey.” Sociological Methods & Research, doi:10.1177/0049124119875959.

- Stenner, K. 2005. The Authoritarian Dynamic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stenner, K. 2009. “Three Kinds of Conservatism.” Psychological Inquiry 20 (2/3): 142–159. doi: 10.1080/10478400903028615

- Van Assche, J., A. Roets, A. Van Hiel, and K. Dhont. 2019. “Diverse Reactions to Ethnic Diversity: The Role of Individual Differences in Authoritarianism.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 28 (6): 523–527. doi: 10.1177/0963721419857769

- Van der Noll, J. 2014. “Religious Toleration of Muslims in the German Public Sphere.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 38: 60–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.01.001

- Van der Noll, J., E. Poppe, and M. Verkuyten. 2010. “Political Tolerance and Prejudice: Differential Reactions Toward Muslims in the Netherlands.” Basic and Applied Social Psychology 32 (1): 46–56. doi: 10.1080/01973530903540067

- Van de Werfhorst, H. G., and F. Van Tubergen. 2007. “Ethnicity, Schooling, and Merit in the Netherlands.” Ethnicities 7 (3): 416–444. doi: 10.1177/1468796807080236

- Vermunt, J. K., and J. Magidson. 2002. “Latent Class Cluster Analysis.” In Applied Latent Class Models, edited by J. Hagenaars, and A. McCutcheon, 89–106. New York: Cambridge.

- Zárate, M. A., and M. Shaw. 2010. “The Role of Cultural Inertia in Reactions to Immigration on the U.S./Mexico Border.” Journal of Social Issues 66 (1): 45–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01632.x

- Zárate, M. A., M. Shaw, J. A. Marquez, and D. Biagas. 2012. ‘Cultural Inertia: The Effects of Cultural Change on Intergroup Relations and the Self-Concept.’ Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 48 (3): 634–645. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.12.014