?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

About 80 million people were displaced worldwide at the end of 2020. To support this highly vulnerable group, in recent years, local bottom-up initiatives proliferated to support refugee integration in hosting communities. This study examines a network intervention for refugees in collaboration with a social start-up whose mission is to match refugees and local volunteers to form friendships. We apply an innovative randomised controlled trial approach with 446 participants integrated into a survey of almost 8000 randomly sampled refugees who moved to Germany between 2013 and 2016. Despite the field experimental study design, statistical imbalances between treatment and control groups arise in the process of enrolment and matching up to the re-interview approximately one year after recruitment, which we address using propensity score weighting. Out of 85 successfully matched individuals, for the 30 refugees with the highest intensity of the intervention we find positive treatment effects on social connectedness, housing satisfaction, and, although less robust, German language proficiency. Thus, a general-purpose mentoring program can promote subjective integration. Effects on objective indicators, such as employment, may only indirectly come about in the longer run.

Introduction

At the end of 2020, the number of displaced persons was 82.4 million globally; a historic high (UNHCR Citation2020). While most refugees are either internally displaced or fled to neighbouring countries, a significant number of refugees live in industrialised countries. Europe (including Turkey) is currently a lead recipient of refugees, where the aftermath of the Arab Spring and the subsequent Syrian civil war led to 6.5 million refugees. These numbers speak to millions of refugees and their fates, but also illustrate a great challenge for the receiving countries. Once refugees arrive in host countries, they are disadvantaged in terms of labour market integration, wellbeing, and social inclusion, compared to other migrants as well as the native population (Brell, Dustmann, and Preston Citation2020). This is the result of traumatic events from war and persecution prior to migration and during escape (Walther et al. Citation2020), interrupted educational and labour market biographies, as well as a lack of institutional and cultural knowledge due to the unplanned migration episode, separation from kin, and wider social support networks (Nickerson et al. Citation2010; Löbel Citation2020).

Government programs geared toward refugee support and integration are sometimes unable to cater to those needs. The rapid arrival of more than 1 million asylum seekers in Europe in 2015 alone created an acute shortage of housing, integration and language courses (Speth and Bojarra-Becker Citation2017; Van Ballegooij and Navarra Citation2018). Non-government initiatives filled some of these gaps, often drawing heavily on volunteers to provide their services. In Germany in 2016, 6% of the population volunteered directly to support refugees (Jacobsen, Eisnecker, and Schupp Citation2017).Footnote1 A relatively new, but proliferating form of non-government grassroots support has come about: refugee mentoring programs, which, in Germany by 2019, brought together around 100,000 refugees with local volunteers. These privately organised programs, but partly funded by the government (BMFSFJ Citation2019), pair refugees with local mentors. Thereby, they deliberately create bridging ties; i.e. ties that connect networks with otherwise few connections and are especially valuable for transmission of resources and information. Participants gain access to material, informational, and/or motivational resources they usually have limited access to (Ooka and Wellman Citation2003; Lancee and Hartung Citation2012). As an additional advantage, non-government mentoring programs offer more personal and personalised support on more equal footing and may be more attuned to individual needs.

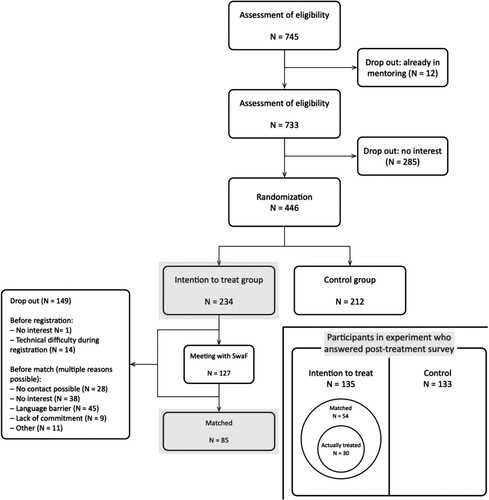

In short, mentoring for refugees introduces a promising tool for promoting integration and bolstering agency among refugees by means of a low-cost network intervention. However, research that studies the actual impact of participation in mentoring programs is scarce and often faces the challenge of self-selection in participation. Using an innovative field experimental design, we investigate to what extent a general mentoring program in Germany with local volunteers as mentors can support refugee integration. For recruitment of participants, as well as baseline and outcome measurement, our empirical analysis builds upon the existing large-scale and well-established longitudinal IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees (Goebel et al. Citation2018; Kroh et al. Citation2017), which is representative for the adult refugee population that arrived in Germany between 2013 and 2016. We recruited 446 refugees that expressed general interest in a mentoring initiative after a short explanation of the program. In order to avoid non-random selection of participants – the most critical point in program evaluation research in general and mentoring in particular (Allen, Poteet, and Russell Citation2000) – refugees were randomly assigned into participation (treatment) and non-participation (control) group. Nevertheless, after initial randomisation, selection in the enrolment and matching process, as well as panel attrition created retrospectively statistical imbalances between the pre-treatment characteristics of individuals in the treatment and control groups. Out of 234 individuals that were initially recruited in the treatment group, 85 could be matched successfully. In the post-treatment survey, 54 could be re-interviewed, 30 of which we define as actually treated, i.e. having experienced a stable tandem relationship of at least several months. Empirically, we address the selection problem by means of propensity score weighting (PSW), for which we benefit from the embedding of our study in the extensive SOEP questionnaire. One year after recruitment, our propensity-score weight adjusted regressions show positive treatment effects on refugees’ social connectedness, housing satisfaction, and, although less robust, German language proficiency. Moreover, the effect sizes largely depend on the intensity of mentoring. Effects on objective indicators, such as employment, may only indirectly come about in the longer run.

In order to increase the ecological validity of our experiment, we used an already existing mentoring program with well-established structures, staff, and locations that are active in real life. To this end, we collaborated with the non-profit organisation Start with a Friend (SwaF), which established itself in response to the increased influx of refugees to Germany. SwaF’s main goal is to establish a friendship relation. Mentoring pairs typically spend time with each other in open-format meetings at least once a week for two hours. Since 2015, the German Federal Government funds SwaF, which allowed the organisation to expand to other cities, where local volunteers built new communities of mentors and mentees. When discussions about our project’s design started in late 2016, the association was active in 14 major German cities and had matched over 2000 refugees with local volunteers.Footnote2 In 2019, SwaF reported more than 5000 matches – a number that is still growing. Today, SwaF runs one of the most professionalised voluntary-based mentoring programs and related activities in Germany.

Mentoring constitutes an under-researched topic in the migration and integration literature. Previous research has mostly focused on the role of legal institutions and governmental practices for refugee integration. While such programs are important, many mentoring programs follow a grassroots approach and are organised by non-governmental organisations. Understanding such programs thus contributes important knowledge for academic research, practitioners and public policy. From an academic perspective, we provide rigorous evidence on the impact of mentoring on different domains of refugee integration, contributing to a broader understanding of the integration process that goes beyond the narrow employment outcome. Also, our experimental research design implemented in a large-scale panel survey overcomes methodological weaknesses in related mentoring research. From a practitioner’s perspective, the analysis of mentoring relationships provides valuable knowledge on how to support refugees during the integration process. From a public policy perspective, assessing the effectiveness of mentoring programs is key for allocating effectively public funding.

Our findings matter beyond the German national context because refugees in most host countries share the highly vulnerable initial conditions for integration as a result of the underlying humanitarian reasons behind forced migration. Also, with regard to the necessity of establishing social contacts with locals or people who have been living for a longer period of time in the country, they face similar challenges in integrating into society. Therefore, the results of our study are transferable to the many similar grassroots initiatives that exist in the main destination countries for refugees around the world.

Integration and social networks

For the purpose of our study, we employ Ager and Strang’s multi-dimensional concept of integration along three categories: markers and means, social connection and facilitators (Citation2008).Footnote3 The three categories subsume a total of nine integration dimensions that can be empirically operationalised. With employment, education, housing, and health, markers and means comprise indicators that are relatively well and objectively measurable and commonly understood in the public debate as evidence of successful integration. Research consistently finds that refugees have poorer health and are slower to find work compared to migrants who migrate for other motives (Brell, Dustmann, and Preston Citation2020). Although both lower employment rates and quality can partly be explained by lower education levels, few refugees invest in formal educational degrees upon arrival (Damelang and Kosyakova Citation2021).

In the social connection dimension, Ager & Strang refer to social capital of refugees, which can be understood both as an end in itself and as a basic prerequisite for successful integration into other areas of society. Bridging ties seem especially important for refugee integration into the host society (Granovetter Citation1973; Gericke et al. Citation2018; Portes Citation1995). For new immigrants, stable ties to established residents may provide key resources such as language training, information on the German education system, labour and housing market, implicit cultural knowledge, among many other areas. Additionally, social ties are prime vehicles of social participation (Degenne and Lebeaux Citation2005), and positive intergroup contacts can foster social cohesion by decreasing stereotypes and prejudice between group members (Allport Citation1954; Domínguez and Maya-Jariego Citation2008; Pettigrew and Tropp Citation2006). However, bridging ties for new immigrants are relatively rare and fragile (Burt Citation2002; Lin Citation2000) because social ties are largely governed by the ‘homophily principle’ (Wimmer and Lewis Citation2010); individuals bond with others who share similar characteristics, particularly with regard to race and ethnicity (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, and Cook Citation2001). Intervention programs aimed at engineering bridging ties – such as the one studied in this article – work, in essence, by circumventing how opportunities normally shape bridging tie formation in everyday life. They create artificial opportunity for meeting, by bringing people of different groups in contact directly, in one-on-one meetings and/or collective events. In our setting, SwaF establishes contact between locals and refugees directly, and thus engineers the opportunity normally afforded through shared interaction contexts. In this sense, the intervention program is a substitute for opportunities for migrants and locals unavailable to most in their daily life.

Facilitators refer to individual and context characteristics that facilitate the integration process. On the part of the refugees, this refers to individual knowledge of the language and culture of the host country, which has been shown in numerous studies to be important for the integration of migrants. Language skills, for example, improve both the transferability of human capital acquired in the country of origin to the host country (Berman, Lang, and Siniver Citation2003) and the efficiency of educational investments after migration (Schnepf Citation2006). This translates also into better labour market integration in terms of higher employment rates and wages (Chiswick and Miller Citation2002; Dustmann and Fabbri Citation2003). Moreover, language proficiency facilitates integration into society through interaction with natives (Martinovic, van Tubergen, and Maas Citation2009) and may even continue over generations, as existing evidence suggests that parents’ language skills influence their children’s educational and employment trajectories (Heath, Rothon, and Kilpi Citation2008).

Context characteristics refer to the attitudes of the local resident population toward the newly arriving refugees. Integration is often perceived as a one-way process on the part of immigrants. However, this overlooks that the host society must also be willing and committed to integrate newcomers into a wide range of social spheres. In a migration-friendly society, encounters and communication between natives and immigrants occur and thus foster integration. Conversely, an anti-immigrant environment may trigger backlash if immigrants segregate themselves in response to negative experiences and maintain their norms and practices (Abdelgadir and Fouka Citation2020).

Taken together, Ager, Strang's multi-dimensional concept of integration, located at different stages of the integration process, gives us a comprehensive overview of the potential treatment effects to be expected from participation in the mentoring program.

Mentoring

The world's most famous mentoring program has given insights into the power of agency created through network interventions: the Big Brothers Big Sisters Program (Grossman and Rhodes Citation2002) served more than 2 million children and adolescents in the US over the past 10 years according to own figures. Apart from mentoring for (non-refugee) immigrants (Joona and Nekby Citation2012), the approach has seen increasing use in other fields, too, such as adolescent health (DuBois and Silverthorn Citation2005), professional development, and education (Eby et al. Citation2008). Research suggests that participation in mentoring programs can have positive and long-term impacts for mentees (DuBois et al. Citation2011). Reviewing different kinds of mentoring programs, Eby et al. find that mentoring most consistently affects mentees’ attitudes and believe systems and, to a lesser degree, objective outcomes such as education and health (Eby et al. Citation2008). Moreover, the stronger the mentoring relationship is, the better results in terms of subjective positive change in beliefs about the own situation can be expected through its social influence (Proestakis et al. Citation2018). Saying this, mentoring can be a tool for behavioural and individual change by means of the increase of a supportive network.

These encouraging findings primarily stem from evaluations of mentoring programs in early childhood education, educational attainment of students with low socio-economic status (Reynolds and Hayakawa Citation2011; Campbell et al. Citation2002; Schweinhart et al. Citation2005), and career mentoring (Wanberg, Welsh, and Hezlett Citation2003). In the refugee integration literature, studies that evaluate the impact of refugee mentoring programs beyond the narrow outcome of employment (Månsson and Delander Citation2017; Battisti, Giesing, and Laurentsyeva Citation2019) are entirely absent.

Methods

Data

Refugees (Mentees)

The baseline for the study is the IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees in Germany, a probability-sampled, longitudinal household survey of refugees in Germany. Survey participants are drawn from the so-called Central Register of Foreigners, in which each foreign national is registered, including information on her or his legal status. In this article, we are using the first three waves of the survey, which cover almost 7500 adults who were interviewed between 2016 and 2018 up to three times. Using appropriate survey weights, the IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees is nationally representative of adult individuals that entered Germany as asylum-seekers between 2013 and 2016, irrespective of their current legal status (Kroh et al. Citation2017). This population is predominantly male, slightly older than 30 and lives in Germany, on average, between 2 and 3 years at the time of recruitment for our study.

Several hundred variables were collected over the survey waves of the IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees, including those related to individual’s migration, employment and education history before migration and integration measures after arrival in Germany. With special attention to the vulnerable group, the questionnaire design deliberately avoided questions about experiences and losses in the country of origin before the escape and provided a simple possibility to not report on traumatic experiences on the escape by means of filtering. For better understanding, respondents could both answer the survey in seven of the most frequent languages among the German refugee population (Arabic, English, Farsi/Dari, German, Kurmanji, Pashtu, Urdu) and with auditory instruments for illiterate survey participants (Jacobsen Citation2019).

Locals (Mentors)

For the scope of our study, local mentors self-selected via word-of-mouth recommendations and street canvassing. Therefore, their recruitment for the study differs from participating refugees (next subchapter). Locals were informed about the study’s objectives and voluntary commitments that come with participation when meeting SwaF staff for the first time. If they were interested in participating, they had to sign a form of consent in a personal meeting with SwaF staff. Refugees in the treatment group were only matched to locals who agreed to participate in the study by signature. We collected information on the local mentors by means of a three-wave web panel, developed at the SOEP and carried out through the Centre for Empirical Social Studies (ZeS) at the Department of Social Sciences of Humboldt University, Berlin. Surveyed locals had previously been successfully matched with a refugee tandem partner. The first survey took place shortly after matching, usually before a first meeting had taken place (N = 73). The second (N = 61) was conducted a few weeks after the kick-off meeting and the third survey (N = 49) was conducted on average about 4 months after the start of tandems.

In , we present some descriptive characteristics of the local volunteers. On average, with about 33 years, they are equally aged as recruited refugees at baseline. More than two-thirds of locals are female and in some form of employment. With 85% having obtained a University entrance qualification, educational attainment is high compared to refugees. Activities carried out jointly in the tandems were mostly eating together (68%) and learning German (34%), whereas only in a minority of cases locals were in fact supporting refugees with job-related issues (20%). For further information on participating locals, we refer to the Appendix: Figures S1 and S2 provide an overview on locals’ motivation to participate in the program and their feedback four months after the start of the mentoring relationship.

Table 1. Local mentor characteristics.

Experimental design

At the end of the interview in 2017 (wave 2 of the IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees, in the field between June-2017 and March-2018), interviewers of the survey institute Kantar Public Germany provided information about the program during face-to-face (CAPI) interviews, including potential joint activities and gains from participation, to refugees living in or close around the 14 cities in which SwaF was active in 2017. Professional interviewer training on the ideas and goals of the mentoring program took place in advance.

The restriction to the area around the 14 cities limits the circle of potential participants to 745 of the roughly 5500 refugees surveyed as part of the IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees in 2017. As part of the program introduction, refugees were informed in advance that program participation is randomly assigned among those interested to participate due to lack of available spots and that their data will be used for scientific purposes, including a match to survey information of the corresponding mentor counterpart. Then, refugees were asked to express or decline their willingness to participate in the mentoring program by signature. Among those eligible and interested (N = 446), we assigned individuals randomly into a treatment (N = 234) and a control group (N = 212). Members of the treatment group were asked to sign a second time to consent to the merging of their survey data with SwaF's process data (e.g. matching and termination dates of tandems). This process guaranteed that respondents understood they were submitting their contact information to a third party. Then, they registered online with SwaF directly during the interview with the support of the interviewer (N = 15 excluded due to technical problems). After registration, SwaF was able to contact and meet personally with 127 registered refugees. Importantly, the organisation provides counselling services for mentors and mentees. If individuals were dissatisfied with the mentoring relation or faced a problem or conflict, they could contact the team and ask for support. Mentors and mentees could end the mentoring program early and drop out of the intervention at any time.

Note that it was in principle possible, though unlikely, for refugees from the control group to receive the treatment by registering with SwaF independently from our study: SwaF’s program is popular, and there is a waiting list of several months up to a year in most SwaF locations. Moreover, SwaF asks all refugees during the registering process how they learned about the program and no participant from the control group mentioned our study. By providing additional funding, our project has resulted in more overall resources being available for SwaF to create additional spots in their mentoring program, rather than having study participants crowding out SwaF’s usual refugee mentees.

Refugees allocated to the treatment group may be treated to varying degrees, depending on how long mentors and mentees met during the mentoring program. Therefore, we distinguish between three levels of treatment intensity, ranging from low (i.) to high (iii.)Footnote4:

Intention-to-treat group (ITT): Everyone randomly selected into the treatment group. This represents the lowest level of treatment intensity (N = 234).

Membership in this group does not necessarily mean someone met with local volunteers and hence received social support. Analysing outcomes for the intention-to-treat group hence allows identifying the effect of this informational intervention and the initial intent to participate.

ii. Matched: Those matched to a local volunteer without necessarily having a physical meeting with the local mentor or a sustained mentoring relationship. This represents a medium level of treatment intensity (N = 85).

The matched group delineates people who were assigned to a volunteer by SwaF but whose mentoring relationship did not necessarily last for the entire period of data collection.

iii. Actually treated: Those matched and regularly participating in the treatment for at least four months. This represents the highest level of treatment intensity (N = 30).

gives an overview of the study design and case numbers over the course of the intervention. Treatment effects are measured in the follow-up survey, approximately one year after recruitment. On average, actually treated individuals respond to the post-treatment survey 340 days after matching (see for summary statistics regarding the durations of treatment across groups). Note, however, that this does not necessarily imply that at the time of evaluation the tandem is still in place.

Table 2. Duration of treatment in days.

Outcomes

The outcomes of our study are derived from the Ager & Strang framework introduced above. First, on the markers and means dimension, we analyse the effect of mentoring on the probability of finding employment, satisfaction with housing, investing in education, and life satisfaction. Second, with regard to the social connection dimension, we analyse the effect of mentoring on refugees’ interactions with Germans relative to non-German persons. Participation in a mentoring program, by definition, increases the network of non-family ties by at least one person that is with high probability German. We cannot empirically distinguish whether this increase is due to the mentor herself/himself or due to third persons. However, this is less problematic for evaluating the success of the intervention, because, first, larger social network diversity promotes integration, regardless of whether caused by the mentor or others. Second, mentoring tandems do not necessarily persist over the course of the year (as our data show). Thus, having retained the local as a social relation speaks to the success of mentoring programs such as SwaF.

Still, it remains an open question whether refugees recognise more contacts to German persons as a source of novel and valuable information. Therefore, we analyse the perceived availability of emotional social support from non-family network members. As part of the social connection dimension, we also investigate social links in terms of practices of general public activities: participation in leisure activities, cultural events (such as visits to restaurants, sports events, cinemas, concerts), and government-supplied integration courses.Footnote5

Third, in our study, the facilitators dimension comprises language speaking proficiency and worries about xenophobic attitudes in the host country (as an indicator of perceptions of safety and stability). We may expect that contact to locals through mentoring increases trust in the host population and thereby decreases worries about xenophobia. This expectation would be in line with contact theory, which stipulates that exchange between groups has a positive impact on the perception of the out-group (Allport Citation1954).

shows how we apply the framework in our study and the Appendix provides details on the coding of variables (Table S1).

Table 3. Classification of outcome indicators.

Results

Pre-treatment balancing

The randomised controlled trial (RCT) design intends to rule out concerns about self-selection into the program based on characteristics that are related to the willingness to participate. Indeed, besides a small and statistically significant difference at the 10 percent level in education and length of stay, through randomisation the intention-to-treat and control groups show no significant differences at baseline amongst basic socio-demographic characteristics as well as the baseline values of the integration indicators of interest (panel A of and ). Most refugees arrived from Syria, followed by Afghanistan and Iraq and arrived between two and three years prior to the baseline interview. Males with a mean age of 33 years make up two thirds of the overall sample population, reflecting the relatively young and predominantly male population that came to Germany between 2013 and 2016. Around 60% of refugees in the sample are married, and more than half have children below age 16. With approximately 40%, a large part of the refugees only obtained primary education. More than two thirds of refugees have an approved refugee status.

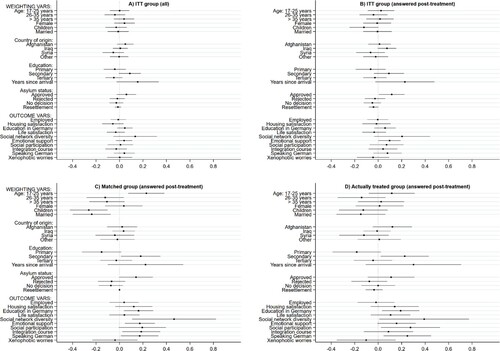

Figure 2. Pre-treatment balancing (univariate), unweighted. Data: IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees (2020). Notes: The squares show the differences in means between the treatment and control groups (treatment – control). The bars represent the 95% confidence intervals. ITT = Intention-to-Treat. In panel (A), the sample also includes respondents who do not participate in the follow-up survey in 2018, at the time of the evaluation of the tandems, due to panel attrition. Table 4 and Tables S3–S5 in the Appendix present the information in tabular form.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics at baseline.

Despite the statistical balance of the groups before the treatment, systematic panel attrition occurs until the evaluation of mentoring relations in the subsequent, post-treatment panel survey. As shown in panels (B–D) of , this creates distributional imbalances in characteristics between the three treatment intensities and the control group (for more details, see Appendix Tables S3–S5). For example, refugees with approved asylum status and those who already had emotional social support outside the family are overrepresented in the ITT group compared to the control group in the follow-up post-treatment interview. In addition, further selection mechanisms may take place, ranging from the successful initial contact with SwaF, over finding a local mentor, up to the retention of a stable mentoring relationship.

If the characteristics driving the selection processes also shape the integration of refugees, this violates the conditional independence assumption (CIA) and produces biased treatment effects (Heckman Citation1979; Groves and Peytcheva Citation2008). To address this issue, we estimate propensity score weights – giving more weight to underrepresented individuals in the treatment group and vice-versa – to achieve pre-treatment balancing between treatment and control groups in terms of integration (outcome) indicators, sociodemographic characteristics, and asylum status. This approach is well-established in the treatment evaluation literature and has previously been adopted in the context of mentoring (Gaddis Citation2012). As long as selection occurs exclusively on observable characteristics and the propensity score model is correctly specified, weighted regressions on the association between treatment and the different integration indicators eliminate selection bias (Rosenbaum Citation1987). By its very nature, it is difficult to empirically disprove that the CIA is violated by unobservable characteristics. No universal answer exists; rather, the answer depends on the setting of the intervention being studied. Since the available literature on mentoring does not provide insights, in robustness checks we include pre-treatment characteristics in our propensity score model that are typically unobserved in empirical analyses but turned out to be important in more or less related contexts: the Big Five personality traits and self-stated risk preferences.Footnote6 Additionally, we test for the power of (i) having utilised other supportive measures than mentoring in Germany and (ii) refugees’ attitudes towards women’s equal rights in explaining selection into treatment, given that the majority of local mentors is female (see ).Footnote7

For our main analyses, we include factors in the propensity score models that differ statistically significantly in univariate mean comparisons between treatment and control group (as carried out in and Tables S3–S5 in the Appendix). Specifically, we estimate the following maximum-likelihood logit regressions to obtain predictions for the probability of assignment of individual i to the treatment group with intensity

relative to the control group:

where

denotes the vector of individual- and household-level pre-treatment characteristics that were statistically unbalanced between treatment and control group, based on the mean comparison. The corresponding propensity score weights are calculated as:

This procedure yields three propensity score weights for each individual i. First, the propensity scores for the lowest treatment intensity (ITT) correct for differences in pre-treatment characteristics that arise exclusively from panel attrition until the next survey period one year later. Second, the scores for the medium intensity (matched) additionally correct for systematic differences in the baseline characteristics of refugees that SwaF was able to match, compared to the control group. Third, scores for the highest treatment intensity (actually treated) correct for panel attrition, baseline characteristics of refugees that were matched, and additionally consider characteristics of refugees having a minimum duration of the mentoring relationship of four months.

There is no consensus in the literature which variables to include in the calculation of propensity score weights. Different strategies exist – varying from using all possible confounding factors of a theoretical model, over using only confounding and significant factors in bivariate models, to using variables that significantly explain differences in multivariate models. Table S6 in the Appendix gives an overview over the included predictors in the set of propensity score weights constructed in our study. The main results presented in this manuscript use our preferred weights (no. 2 in Table S6). This conservative strategy achieves pre-treatment equality in the mean values between treatment and control group along all outcome dimensions as well as all relevant socio-demographic characteristics, length of stay in Germany and asylum status (Tables S7–S9 in the Appendix). Figure S3 in the Appendix shows that propensity scores fulfil common support between treatment and control group.

Treatment effects one year after the intervention

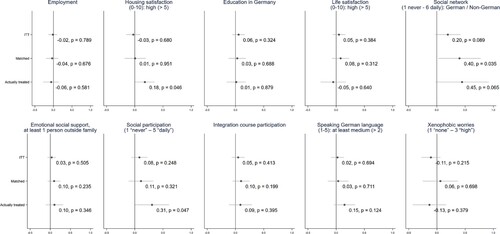

Approximately one year later, in the 2018 wave of the survey (in the field between September-2018 and February-2019), we measure the treatment effect of mentoring on the integration of the participating refugees as compared to the control group. In our main analyses, we conduct propensity score weight-adjusted OLS regressions to estimate average treatment effects separately for the intention-to-treat, matching, and actual treatment groups relative to the control group. reports coefficients and confidence intervals for the integration measures of interest. As robustness checks, we provide in the Appendix, first, treatment effects for six alternative weighting strategies (Figure S4 and Table S10) and, second, include weighting variables as confounders (Tables S11 and S12). Additionally, since outcomes are measured on different scales, we have opted to present results in relation to standard deviations using Cohen’s d (Table S13).

Figure 3. Treatment effects across integration indicators. Data: IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees (2020). Notes: The bars in each box represent the 95% confidence intervals of weighted univariate regressions using our preferred weights. All treatment effects are stated relative to the control group.

Markers and means

Our empirical results do not provide evidence for a statistically significant treatment effect in terms of employment (, upper left panel). Coefficients in the bivariate weighted regressions are small and even slightly negative. However, we find a statistically significant 18 percentage point increase in reported high levels of housing satisfaction. Refugees are very mobile in the first years after arrival and often end up in low-quality accommodation (Harte, Childs, and Hastings Citation2009), a trend that is likely to have intensified in urban areas worldwide in recent years in view of rising property prices. Although we cannot empirically test which mechanism drives the improvement in housing satisfaction among treated refugees due to data limitations, our results suggest that the social network provided by mentoring supports refugees to seek higher-quality housing.

For participation in any form of education since arrival in Germany, we do not find statistically robust effects. Regarding overall life satisfaction, we may expect, on the one hand, that satisfaction of the treatment group will increase compared to the control group, given that mentoring usually boosts self-esteem and a sense of belonging (DuBois and Silverthorn Citation2005). On the other hand, the geographical location and thus the degree of threat to family members is a major factor determining the wellbeing of refugees (Nickerson et al. Citation2010; Löbel Citation2020; Löbel and Jacobsen Citation2021), a factor that cannot be changed by informal mentors. Empirically, the treatment effect on refugee participants’ life satisfaction is close to zero across all treatment scenarios and statistically insignificant.

Social connection

Research on mentoring suggests participation should have a positive effect on emotional social support (Dubois et al. Citation2002). However, our results do not provide meaningful effects for the level of emotional social support from outside the family network. Instead, we find a statistically significant (medium-sized in terms of Cohen’s D) increase in the ratio of spending time with Germans relative to non-Germans in the social network for the matched and the actually treated groups. In addition, we observe a statistically significant increase in the average frequency of social leisure activities and cultural events of individuals in the treatment groups compared to individuals in the control group. This effect increases with treatment intensity up to 0.31 (p = 0.05) on the scale from 1 (never) to 5 (daily) for the actually treated group (Cohen’s d = 0.53; medium-sized effect).

Lastly, mentoring does not statistically influence the probability of participation in integration courses, probably because post-treatment the large majority (85%) had already participated or was currently in integration and language programs (de Paiva Lareiro, Rother, and Siegert Citation2020).

Facilitators

By meeting regularly, participating refugees expose themselves to the German language through direct conversation with the mentor and others. Indeed, we observe a positive treatment effect on the reported language (speaking) proficiency that becomes stronger with increasing treatment intensity. In the actually treated group, the share of those who report at least medium German speaking skills increases by 15 percentage points, which corresponds roughly, assuming linearity, to an extra year of stay in Germany (de Paiva Lareiro, Rother, and Siegert Citation2020). Although the effect does not reach statistical significance (p = 0.124) with our preferred weighting strategy, five of the seven alternative weights show statistically significant results at conventional significance levels (Appendix, Figure S4 & Table S10). Finally, concerning our last examined integration dimension, we do not find a significant reduction in the subjectively reported degree of worries about xenophobia for any notion of treatment intensity.

Discussion

Although general-purpose mentoring programs for refugees make up the majority of non-governmental grass root organisations, so far, little is known about their effectiveness. Our study aims at filling this gap by evaluating an established non-government mentoring program for refugees using a field experimental approach nested in a large-scale panel survey. In collaboration with the social start-up Start with a Friend (SwaF), we introduced a general-purpose, low-threshold mentoring program to refugees who recently arrived to Germany.

Overall, our analysis shows that such bottom-up interventions have medium-sized positive effects on the social connection dimension, namely the ethnic composition of the participants’ social network, and the average frequency of social leisure and cultural activities refugees take part in. Also, participating refugees show increased satisfaction with their own accommodation, which is presumably the result of the mentors’ support in finding higher-quality housing. Although not visible using the most conservative weighting strategy chosen for our main analyses, statistically significant improvements in language skills are found in the majority of alternative weighting scenarios. In line with previous findings, the size of effects increases with treatment intensity (Bakker et al. Citation2019).

Also, our findings are in line with the available meta-literature on mentoring (Eby et al. Citation2008) by showing positive treatment effects in indicators that may be regarded as subjective. Moreover, the findings match with SwaF’s mission statement to offer a refugee mentoring program that creates friendships ‘at eye level.’ Accordingly, promotion of participation in social activities of everyday life is the most natural dimension where positive effects can be expected from the intervention and may well go beyond the direct circle of participants. Through referrals or information transfer snowball and spillover effects to families, friends, and acquaintances may occur (Dahl, Løken, and Mogstad Citation2014).

However, no effects are found for markers and means. One reason for the absence of statistically significant treatment effects on employment is that, unlike some governmental mentoring programs (Månsson and Delander Citation2017; Battisti, Giesing, and Laurentsyeva Citation2019), SwaF does not explicitly aim at influencing refugees’ labour market participation. Additionally, most mentors in our study (32%) are 25 years and younger, and 30% have not yet completed their vocational training or studies. Hence, bridging ties initiated by the program are unlikely to provide network resources that directly relate to increases in employment chances for refugees. However, studies have shown the high relevance of language skills for acquiring destination-specific human capital. Therefore, initiatives such as SwaF’s may indirectly promote integration even on the means and markers dimensions in the longer run (Chiswick and Miller Citation2002).

We are optimistic that the findings of this analysis are robust and externally valid. First, the sample population was recruited through stratified random sampling from the overall refugee population in Germany. Since refugees in Germany share major attributes (e.g. experience of traumata, socio-demographic characteristics) with other refugee populations, results promise to hold important insights for other national contexts. Second, our participants were assigned randomly to the mentoring program and the staff and places in the study are identical with the real-life intervention.

Nevertheless, three caveats remain. First, the program under evaluation was only administered in 14 large German cities, which excludes rural areas from the analysis. We regard this as only a minor limitation to the external validity of our findings because most grass roots (non-government) mentoring programs are situated in urban areas, and the refugee population is much more concentrated in urban areas compared to the overall population (Rösch et al. Citation2020). Also, we do not expect that contamination effects and spill overs between cities take place, given the geographic diversity of the localities of the study (Proestakis et al. Citation2018). Second, panel attrition reduces the group of those whose tandem lasted at least a few months and who could be interviewed in the post-treatment survey to 30 persons. This does not allow for statistically reliable heterogeneity analyses, for instance along sociodemographic characteristics. Third, despite random assignment into intention-to-treat and control group, we observe selection over subsequent stages of implementation. Although we corrected for selection by applying propensity score weights, the results may not necessarily apply to, for example, refugees with very low language skills as they mostly did not receive a local mentor. Still, lack of language skills is a minor problem in English-speaking host countries.

Overall, we interpret our findings as providing encouraging evidence for the effectiveness of volunteering mentors in promoting social integration of refugees. As long as enough and high-quality volunteers are available, mentoring programs basically offer high scalability at low cost compared to government programs. In this sense, they should be seen complementary to more professionalised, targeted initiatives with trained personnel, such as support with legal issues, job search, or housing.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (1.2 MB)Acknowledgments

We thank Start with a Friend e.V. for their energy to continuously forge new ties between locals and refugees and for their trust to have us observe the mentoring relationships along the way.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All data on refugee participants, including the outcome measures, are based on secondary analyses of completely anonymised survey data that is publically available (as part of version 36 of the Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP Citation2021). These data can only be accessed for research purposes and after contractual agreement with the Research Data Centers of the DIW-Berlin or the IAB. All data is delivered with detailed documentation as part of the comprehensive and well-established documentation of the general SOEP Survey. Further information on accessing SOEP-data can be obtained here: https://www.diw.de/en/diw_02.c.222829.en/access_and_ordering.html.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In the following, the term ‘refugees’ refers to individuals whose asylum applications have been approved according to the Convention Relating to the Status on Refugees or the German Constitution (Grundgesetz) Art. 16a as well as people with subsidiary protection, asylum seekers (waiting for their decision), people with a suspension of deportation (Abschiebeschutz) and those whose asylum applications have been rejected but are tolerated to stay in the country (Duldung).

2 Berlin, Potsdam, Hamburg, Oldenburg, Leipzig, Dresden, Cologne, Dusseldorf, Bonn, Frankfurt on the Main, Aachen, Stuttgart, Landau and Freiburg.

3 We do not consider the category foundation, which refers to rights and citizenship and thus to legal aspects of integration. The reason is that most refugees in our data have an approved asylum status at the time of recruitment, which means that they already have a secured residence title.

4 The stepwise definition of the treatment means that all persons in treatment groups (ii) and (iii) also belong to the treatment groups of the respective lower treatment intensities. Furthermore, the control group comprises a constant circle of individuals for all treatment intensities.

5 Integration courses are carried out nationwide under the direction of the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) and constitute the most encompassing integration program. They usually provide the first opportunity to formally acquire language skills. They are usually comprised of 600 hours; however, targeted formats with varying hours are available. Additionally, orientation classes provide information on Germany legal, cultural, and historic issues.

6 Nyhus and Pons (Citation2005) have identified psychological personality traits as significant wage determinants. Belzil and Leonardi (Citation2007) as well as Breen, Van De Werfhorst, and Jæger (Citation2014) have shown that risk attitudes influence educational decisions.

7 Results are available upon request. In a nutshell, the Big Five dimension ‘Conscientiousness’ and the ‘prior use of counseling services offered by the Federal Employment Agency’ favour selection into the treatment group. Unfortunately, these variables are only available for a subset of the refugees at the time of recruitment. Due to the resulting decrease in the number of cases, the main results of our paper on the treatment effects of the intervention indeed remain qualitatively unchanged when both factors are included in the weighting model (in terms of point estimates), but the confidence intervals become wider.

References

- Abdelgadir, Aala, and Vasiliki Fouka. 2020. “Political Secularism and Muslim Integration in the West: Assessing the Effects of the French Headscarf Ban.” American Political Science Review 114 (3): 707–723. doi:10.1017/S0003055420000106.

- Ager, Alastair, and Alison Strang. 2008. “Understanding Integration: A Conceptual Framework.” Journal of Refugee Studies 21 (2): 166–191. doi:10.1093/jrs/fen016.

- Allen, Tammy D., Mark L. Poteet, and Joyce E. A. Russell. 2000. “Protégé Selection by Mentors: What Makes the Difference?” Journal of Organizational Behavior 21 (3): 271–282. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(200005)21:3<271::AID-JOB44>3.0.CO;2-K.

- Allport, G. W. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. New York, NY: Addison-Wesley.

- Bakker, Arthur, Jinfa Cai, Lyn English, Gabriele Kaiser, Vilma Mesa, and Wim Van Dooren. 2019. “Beyond Small, Medium, or Large: Points of Consideration When Interpreting Effect Sizes.” Educational Studies in Mathematics Volume 102: 1–8. doi:10.1007/s10649-019-09908-4.

- Battisti, Michele, Yvonne Giesing, and Nadzeya Laurentsyeva. 2019. “Can Job Search Assistance Improve the Labour Market Integration of Refugees? Evidence from a Field Experiment.” Labour Economics 61 (December): 101745. doi:10.1016/j.labeco.2019.07.001.

- Belzil, Christian, and Marco Leonardi. 2007. “Can Risk Aversion Explain Schooling Attainments? Evidence from Italy.” Labour Economics 14 (6): 957–970. doi:10.1016/J.LABECO.2007.06.005.

- Benyamini, Yael, Howard Leventhal, and Elaine A. Leventhal. 2004. “Self-Rated Oral Health as an Independent Predictor of Self-Rated General Health, Self-Esteem and Life Satisfaction.” Social Science and Medicine 59 (5): 1109–1116. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.021.

- Berman, Eli, Kevin Lang, and Erez Siniver. 2003. “Language-Skill Complementarity: Returns to Immigrant Language Acquisition.” Labour Economics 10 (3): 265–290. doi:10.1016/S0927-5371(03)00015-0.

- BMFSFJ. 2019. “Menschen Stärken Menschen.” https://www.bmfsfj.de/bmfsfj/themen/engagement-und-gesellschaft/engagement-staerken/menschen-staerken-menschen/menschen-staerken-menschen/107820.

- Breen, Richard, Herman G. Van De Werfhorst, and Mads Meier Jæger. 2014. “Deciding Under Doubt: A Theory of Risk Aversion, Time Discounting Preferences, and Educational Decision-Making.” European Sociological Review 30 (2): 258–270. doi:10.1093/ESR/JCU039.

- Brell, Courtney, Christian Dustmann, and Ian Preston. 2020. “The Labor Market Integration of Refugee Migrants in High-Income Countries.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 34 (1): 94–121.

- Burt, Ronald S. 2002. “Bridge Decay.” Social Networks 24 (4): 333–363. doi:10.1016/S0378-8733(02)00017-5.

- Campbell, Frances A., Craig T. Ramey, Elizabeth Pungello, Joseph Sparling, and Shari Miller-Johnson. 2002. “Early Childhood Education: Young Adult Outcomes from the Abecedarian Project.” Applied Developmental Science 6 (1): 42–57. doi:10.1207/S1532480XADS0601_05.

- Chiswick, Barry R., and Paul W. Miller. 2002. “Immigrant Earnings: Language Skills, Linguistic Concentrations and the Business Cycle.” Journal of Population Economics 15 (1): 31–57. doi:10.1007/PL00003838.

- Dahl, Gordon B., Katrine V. Løken, and Magne Mogstad. 2014. “Peer Effects in Program Participation.” American Economic Review 104 (7): 2049–2074. doi:10.1257/aer.104.7.2049.

- Damelang, Andreas, and Yuliya Kosyakova. 2021. “To Work or to Study? Postmigration Educational Investments of Adult Refugees in Germany – Evidence from a Choice Experiment.” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 73 (June): 100610. doi:10.1016/J.RSSM.2021.100610.

- Degenne, Alain, and Marie Odile Lebeaux. 2005. “The Dynamics of Personal Networks at the Time of Entry Into Adult Life.” Social Networks 27 (4): 337–358. doi:10.1016/J.SOCNET.2004.11.002.

- de Paiva Lareiro, Cristina, Nina Rother, and Manuel Siegert. 2020. “Geflüchtete Verbessern Ihre Deutschkenntnisse Und Fühlen Sich in Deutschland Weiterhin Willkommen.” BAMF-Kurzanalyse 1. https://www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Forschung/Kurzanalysen/kurzanalyse1-2020_iab-bamf-soep-befragung-sprache.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=5.

- Domínguez, Silvia, and Isidro Maya-Jariego. 2008. “Acculturation of Host Individuals: Immigrants and Personal Networks.” American Journal of Community Psychology 42 (3–4): 309–327. doi:10.1007/S10464-008-9209-5.

- Dubois, David L, Bruce E Holloway, Jeffrey C Valentine, and Harris Cooper. 2002. “Effectiveness of Mentoring Programs for Youth: A Meta-Analytic Review.” American Journal of Community Psychology 30 (2), doi:10.1023/A:1014628810714.

- DuBois, David L., Nelson Portillo, Jean E. Rhodes, Naida Silberthorn, and Jeffrey C. Valentine. 2011. “How Effective Are Mentoring Programs for Youth? A Systematic Assessment of the Evidence.” The Public interest 12 (2): 57–91. doi:10.1177/1529100611414806.

- DuBois, David L., and Naida Silverthorn. 2005. “Natural Mentoring Relationships and Adolescent Health: Evidence from a National Study.” American Journal of Public Health 95 (3): 518–524. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2003.031476.

- Dustmann, Christian, and Francesca Fabbri. 2003. “Language Proficiency and Labour Market Performance of Immigrants in the UK.” The Economic Journal 113 (489): 695–717. doi:10.1111/1468-0297.t01-1-00151.

- Eby, Lillian T, Tammy D Allen, Sarah C Evans, Thomas Ng, and David Dubois. 2008. “Does Mentoring Matter? A Multidisciplinary Meta-Analysis Comparing Mentored and Non-Mentored Individuals.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 72 (2): 254–267. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2007.04.005.

- Gaddis, S. Michael. 2012. “What’s in a Relationship? An Examination of Social Capital, Race and Class in Mentoring Relationships.” Social Forces 90 (4): 1237–1269. doi:10.1093/sf/sos003.

- Gericke, Dina, Anne Burmeister, Jil Löwe, Jürgen Deller, and Leena Pundt. 2018. “How Do Refugees Use Their Social Capital for Successful Labor Market Integration? An Exploratory Analysis in Germany.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 105 (April): 46–61. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2017.12.002.

- Goebel, Jan, Markus M. Grabka, Stefan Liebig, Martin Kroh, David Richter, Carsten Schröder, and Jürgen Schupp. 2018. “The German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP).” Jahrbücher Für Nationalökonomie Und Statistik. doi:10.1515/jbnst-2018-0022.

- Granovetter, Mark S. 1973. “The Strength of Weak Ties.” American Journal of Sociology 78 (6): 1360–1380. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-442450-0.50025-0.

- Grossman, Jean B., and Jean E. Rhodes. 2002. “The Test of Time: Predictors and Effects of Duration in Youth Mentoring Relationships.” American Journal of Community Psychology 30 (2): 199–219. doi:10.1023/A:1014680827552.

- Groves, Robert M., and Emilia Peytcheva. 2008. “The Impact of Nonresponse Rates on Nonresponse Bias: A Meta-Analysis.” Public Opinion Quarterly. doi:10.1093/poq/nfn011.

- Harte, Wendy, Iraphne R.W. Childs, and Peter A. Hastings. 2009. “Settlement Patterns of African Refugee Communities in Southeast Queensland.” Australian Geographer 40 (1): 51–67. doi:10.1080/00049180802656960.

- Heath, Anthony F., Catherine Rothon, and Elina Kilpi. 2008. “The Second Generation in Western Europe: Education, Unemployment, and Occupational Attainment.” Annual Reviews 34 (July): 211–235. doi:10.1146/ANNUREV.SOC.34.040507.134728.

- Heckman, James J. 1979. “Sample Selection Bias as a Specification Error.” Econometrica 47 (1): 153–161. doi:10.2307/1912352.

- Jacobsen, Jannes. 2019. “Language Barriers During the Fieldwork of the IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees in Germany.” In GESIS-Schriftenreihe. Surveying the Migrant Population: Consideration of Linguistic and Cultural Issues, edited by Behr Dorothée, 75–84. Cologne: DIW Berlin. https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/58074?locale-attribute=en.

- Jacobsen, Jannes, Philipp Eisnecker, and Jürgen Schupp. 2017. “In 2016, Around One-Third of People in Germany Donated for Refugees and Ten Percent Helped Out on Site – Yet Concerns Are Mounting.” DIW Economic Bulletin 16: 165–176.

- Joona, Pernilla Andersson, and Lena Nekby. 2012. “Intensive Coaching of New Immigrants: An Evaluation Based on Random Program Assignment.” Scandinavian Journal of Economics 114 (2): 575–600. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9442.2011.01692.x.

- Kroh, Martin, Simon Kühne, Jannes Jacobsen, Manuel Siegert, and Rainer Siegers. 2017. “Sampling, Nonresponse, and Integrated Weighting of the 2016 IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees (M3/M4).” SOEP Survey Papers 477: Series C. Berlin.

- Lancee, Bram, and Anne Hartung. 2012. “Turkish Migrants and Native Germans Compared: The Effects of Inter-Ethnic and Intra-Ethnic Friendships on the Transition from Unemployment to Work.” International Migration 50 (1): 39–54. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2011.00736.x.

- Lin, Nan. 2000. “Inequality in Social Capital.” Contemporary Sociology 29 (6): 785. doi:10.2307/2654086.

- Löbel, Lea Maria. 2020. “Family Separation and Refugee Mental Health – A Network Perspective.” Social Networks 61: 20–33. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2019.08.004.

- Löbel, Lea-Maria, and Jannes Jacobsen. 2021. “Waiting for Kin: A Longitudinal Study of Family Reunification and Refugee Mental Health in Germany.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies.” 1–22. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2021.1884538.

- Månsson, Jonas, and Lennart Delander. 2017. “Mentoring as a Way of Integrating Refugees Into the Labour Market – Evidence from a Swedish Pilot Scheme.” Economic Analysis and Policy 56 (December): 51–59. doi:10.1016/j.eap.2017.08.002.

- Martinovic, Borja, Frank van Tubergen, and Ineke Maas. 2009. “Dynamics of Interethnic Contact: A Panel Study of Immigrants in the Netherlands.” European Sociological Review 25 (3): 303–318. doi:10.1093/ESR/JCN049.

- McPherson, Miller, Lynn Smith-Lovin, and James M. Cook. 2001. “Birds of a Feather: Homophily in Social Networks.” Annual Review of Sociology 27: 415–444. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415.

- Nickerson, Angela, Richard A. Bryant, Zachary Steel, Derrick Silove, and Robert Brooks. 2010. “The Impact of Fear for Family on Mental Health in a Resettled Iraqi Refugee Community.” Journal of Psychiatric Research 44 (4): 229–235. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.08.006.

- Nyhus, Ellen K., and Empar Pons. 2005. “The Effects of Personality on Earnings.” Journal of Economic Psychology 26 (3): 363–384. doi:10.1016/J.JOEP.2004.07.001.

- Ooka, Emi, and Barry Wellman. 2003. “Does Social Capital Pay Off More Within or Between Ethnic Groups? Analyzing Job Searches In Five Toronto Ethnic Groups.” In Inside the Mosaic, edited by Eric Fong. http://www.chass.utoronto.ca/~wellman.

- Pettigrew, Thomas F., and Linda R. Tropp. 2006. “A Meta-Analytic Test of Intergroup Contact Theory.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90 (5): 751–783. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751.

- Portes, Alejandro. 1995. The Economic Sociology of Immigration. New York, NY: Russal Sage Foundation.

- Proestakis, Antonios, Eugenia Polizzi di Sorrentino, Helen Elizabeth Brown, Esther van Sluijs, Ankur Mani, Sandra Caldeira, and Benedikt Herrmann. 2018. “Network Interventions for Changing Physical Activity Behaviour in Preadolescents.” Nature Human Behaviour 2 (10): 778–787. doi:10.1038/s41562-018-0436-y.

- Reynolds, Arthur J, and C. M. Hayakawa. 2011. “Why the Child-Parent Center Promote Life Course Development.” In The Pre-K Debates: Current Controversies and Issues, edited by E. Ziegler, 144–152. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

- Rösch, Tabea, Hanne Schneider, Johannes Weber, and Susanne Worbs. 2020. “Integration von Geflüchteten in Ländlichen Räumen.” BAMF Forschungsbericht 36. https://www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Forschung/Forschungsberichte/fb36-integration-laendlicher-raum.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=5.

- Rosenbaum, Paul R. 1987. “Model-Based Direct Adjustment.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 82 (398): 387–394. doi:10.1080/01621459.1987.10478441.

- Schnepf, Sylke Viola. 2006. “Immigrants’ Educational Disadvantage: An Examination Across Ten Countries and Three Surveys.” Journal of Population Economics 20 (3): 527–545. doi:10.1007/S00148-006-0102-Y.

- Schweinhart, L. J., J. Montie, Z. Xiang, W. S. Barnett, C. R. Belfield, and M. Nores. 2005. “Lifetime Effects: The High/Scope Perry Preschool Study through Age 40.” High/Scope Press, 3. http://works.bepress.com/william_barnett/3/.

- SOEP. 2021. “Sozio-Oekonomisches Panel (SOEP), Version 36, Daten Der Jahre 1984-2019.” SOEP-Core V36, EU-Edition. doi:10.5684/soep.core.v36eu.

- Speth, Rudolf, and Elke Bojarra-Becker. 2017. “Zivilgesellschaft Und Kommunen: Lerneffekte Aus Dem Zuzug Geflüchteter Für Das Engagement in Krisen.” Opuscula 107. http://www.opuscula.maecenata.eu.

- UNHCR. 2020. “Figures at a Glance.” https://www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html.

- Van Ballegooij, Wouter, and Cecilia Navarra. 2018. The Cost of Non-Europe in Asylum Policy. Brussels: European Parliamentary Research Service.

- Walther, Lena, Hannes Kröger, Ana Nanette Tibubos, Thi Minh Tam Ta, Christian Von Scheve, Jürgen Schupp, Eric Hahn, and Malek Bajbouj. 2020. “Psychological Distress among Refugees in Germany: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Individual and Contextual Risk Factors and Potential Consequences for Integration Using a Nationally Representative Survey.” BMJ Open. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033658.

- Wanberg, Connie R., Elizabeth T. Welsh, and Sarah A. Hezlett. 2003. “Mentoring Research: A Review and Dynamic Process Model.” Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management 22 (January): 39–124. doi:10.1016/S0742-7301(2003)22.

- Wimmer, Andreas, and Kevin Lewis. 2010. “Beyond and Below Racial Homophily: ERG Models of a Friendship Network Documented on Facebook.” American Journal of Sociology 116 (2): 583–642. doi:10.1086/653658.