ABSTRACT

Several academic fields study how immigrants choose their place of residence when moving to, or within destination countries. Existing studies, however, focus on isolated factors, and we do not know whether political factors matter once we have accounted for well-established determinants. This paper examines the extent to which political factors, such as voting rights for foreign citizens, citizenship policies and popular support for right-populist parties, influence internal mobility decisions of newly-arrived immigrants, relative to other variables. We draw on a 2020 conjoint experiment in Switzerland (N = 1596 participants) in the context of a larger survey of foreign citizens who arrived in Switzerland in the preceding 15 years. The conjoint experiment provides data on the causal effects of contextual factors on mobility decisions, allowing us to assess their relative importance. We show that inclusive political reception contexts constitute a pull factor for immigrants. Exploratory analysis indicates that the size of the effect of the political reception context on residential location choice depends on educational achievement, income, legal status, a feeling of belonging to Switzerland and social networks. We conclude that studies of immigrant location choice should routinely consider political factors.

Introduction

In a world divided into nation states, human mobility can either be internal (within a nation state) or international (across national borders). Worldwide, many people are on the move: estimated at around 740 million internal migrants in 2009 and 272 million international migrants in 2019 (McAuliffe, Khadria, and Bauloz Citation2019). Even if these numbers come with great uncertainty, they underline the misconception that migrants primarily come from another country. This is certainly true for destination countries in Western Europe, like Switzerland, where internal mobility explains more of the spatial distribution than international movements (Wanner Citation2014). Here, we analyse internal mobility under the specific angle of pull factors (Lee Citation1966). In particular, we focus on municipality attributes and how they can attract or deter internal migrants, rather than on the factors that push individuals to leave a place, or how migrants choose a destination country.

The more specific focus of this paper is on understanding whether individuals – in this case recent immigrants – ‘vote with their feet’ (Tiebout Citation1956) for political reasons. Existing explanations of internal mobility with a focus on municipality or city characteristics have largely overlooked political factors. Studies using macro perspectives focus mostly on economic and financial determinants (Alonso Citation1964; Borjas Citation1999; Damm Citation2009; Tiebout Citation1956; Sasser Citation2010). We are aware of only a few studies that emphasise the role of political variables to explain immigrants’ mobility choices (Bracco et al. Citation2018; Slotwinski and Stutzer Citation2019). Their focus is however restricted to anti-immigrant attitudes of the majority population as a deterring factor on the location choice of immigrants. Here we suggest a broader view that not only incorporates attitudes, but also the broader political ‘context of reception’ (Portes and Rumbaut Citation2006), which includes integration policies and citizenship policies that may influence immigrant location choice.

To analyse whether internal mobility is influenced by political factors, the case of newly-arrived immigrants in Switzerland represents a good test scenario because of the federal structure of the Swiss political system. Swiss cantons (i.e. regions) and municipalities play a central role in shaping their own integration and citizenship policies (Probst et al. Citation2019), leading to substantial subnational heterogeneity in the political ‘context of reception’ for foreign citizens (Manatschal Citation2011). Factors such as whether access to citizenship is easy or difficult, whether foreign citizens enjoy voting rights, or whether the local population is rather open or hostile towards migrants can vary greatly from one Swiss municipality to another. For instance, some subnational regions (cantons) grant voting rights to noncitizens while others do not. More precisely, 5 of the 26 Swiss cantons (Neuchâtel, Jura, Vaud, Geneva, and Fribourg) grant noncitizens’ voting rights at the municipal level, and at the cantonal level in Jura and Neuchâtel. Three other cantons delegate the granting of aliens’ voting rights to municipalities (Basel-City, Graubünden, and Appenzell Ausserrhoden). As a result, some municipalities in the canton of Graubünden, such as Masein, provide their noncitizen population the right to vote, whereas most others do not. In all other cantons, noncitizens cannot vote at all (Arrighi and Piccoli Citation2018).

As regards citizenship policies, the naturalisation system is defined by a three-tier system involving the municipal, cantonal, and federal level (Hainmueller and Hangartner Citation2013; Helbling Citation2008, Citation2010), with the federal level setting the general framework for the naturalisation process. However, municipalities have a key role as they act as ‘gatekeepers’ because they formulate their own requirements in addition to those set at the national level. For instance, the residency requirement to apply for naturalisation is 10 years in Switzerland. Within this time frame, municipalities require between 2 and 8 years of residence on their territory (Arrighi and Piccoli Citation2018). Similar heterogeneity appears regarding natives’ attitudes towards immigration: In the 2019 federal elections for the national council, municipal support for the far-right Swiss People’s Party varied from 2.3% to 84.1% (Federal Statistical Office Citation2021).

This article concentrates on recently arrived immigrants, who resided no more than 15 years in Switzerland and are, therefore, somewhat familiar with the local context and subnational heterogeneity, but at the same time less attached to a particular place than individuals who have lived in a place for longer. We stipulate that these circumstances make them more likely to ‘vote with their feet’ for political reasons, which makes it more likely for us to observe more generic mechanisms of location choice. Indeed, a recent study in Switzerland shows that, after having arrived on the territory, 9.1% of international immigrants also move across cantonal borders (Zufferey, Steiner, and Ruedin Citation2021).

Our contribution to the literature is twofold. First, we contribute a broader understanding of factors influencing residential location choice. While existing work has emphasised economic determinants, such as wages, employment rates or buying power as determinants of internal mobility (Dowding, John, and Mergoupis Citation2002; Scott and Brindley Citation2012), we highlight that other macrofactors can also play a role for location choice, notably the political reception context. Knowing that the political reception context affects residential location choice is essential because spatial (re-)distribution matters for the planning of municipal infrastructure, public transport or educational facilities. By using a conjoint experiment, this study can assess the causal influence of the political reception context on immigrants’ intentions as regards their residential location choice. Second, we demonstrate that subnational integration policies shape immigrants’ mobility intentions. Integration policies provide immigrants with material resources that facilitate incorporation into the host society, such as language classes or rights to access the labour market, or symbolic resources that signal to immigrants that they are legitimate members of the host society (Bloemraad Citation2013). By analysing location choice, we adopt a dynamic approach and extend the literature on integration policy outcomes, which focuses predominantly on sedentary factors such as immigrants’ political behaviour and integration (see e.g. Bennour and Manatschal Citation2019; Bloemraad Citation2006; Ersanilli and Koopmans Citation2011; Ersanilli and Saharso Citation2011; Goodman and Wright Citation2015; Koopmans Citation2010).

Theory: location choice of immigrants

Mobility decisions depend on push factors, which make people leave a place, and pull factors – elements in the new place of residence that attract individuals to move there (Lee Citation1966). Here, we focus on pull factors for moves within a country – so-called internal migration. Such residential location choice is studied in many fields from geography to demography to economics (Montgomery and Curtis Citation2006). Existing research covers explanations at the micro or individual, meso or group, and macro, meaning structural levels. The macro perspective shows how structural features can make locations more attractive (Permentier, Bolt, and Van Ham Citation2011), whereas, the meso perspective reveals how group related factors and social networks matter to explain mobility behaviour. The micro level, by contrast, is, for instance, analysed extensively by demographers or anthropologists who study individual drivers of location choice. This micro perspective demonstrates that contextual factors do not affect everyone the same way, highlighting individual preferences among other considerations (see e.g. Lymperopoulou Citation2013).

Among the central micro factors driving individual location choices, the literature identifies lifecycle and lifestyle as major dimensions (Smith and Olaru Citation2013). The lifecycle relates to the evolutionary demographic of a household, like the arrival of a child (Ström Citation2010; Mulder and Lauster Citation2010), getting married (Aassve et al. Citation2007), leaving a job or reaching retirement age (Ermisch and Jenkins Citation1999). All these aspects influence residential location choice. Lifestyle components emphasise the values of individuals (Smith and Olaru Citation2013), which also influence location choice. Subjective values and preferences can lead individuals to choose greener and healthier neighbourhoods, for instance, or the ‘vibe’ of a city (Cao, Mokhtarian, and Handy Citation2009). Evidently, lifestyle and lifecycle also influence each other. Income, age, and change in employment sector can lead to a change in lifestyle, and trigger movement to a new location (Dieleman Citation2001; Walker and Li Citation2007).

At the group level, meso factors also play a role in determining individual location choice, like the types and costs of property on offer (Krizek and Waddell Citation2002). More generally, however, neighbourhood characteristics are a strong determinant of location choice, as they encompass factors such as the predominant kind of lifestyle (Krizek and Waddell Citation2002), the transport system (Montgomery and Curtis Citation2006), access to nature (Kaplan and Austin Citation2004) or recreational activities (Colwell, Dehring, and Turnbull Citation2002). To explain individual mobility choice, studies concerned with meso-level factors look at relatively small contextual units such as a street or a neighbourhood (van Heerden and Ruedin Citation2019). A different literature at the meso level focuses on immigrants in particular, looking at ethnic enclaves or how the share or immigrants in a neighbourhood affects the mobility choices of immigrants (Damm Citation2009; Bhat and Guo, Citation2006; Toussaint-Comeau and Rhine Citation2004). These studies highlight that social networks can play an important role, as people tend to move close to existing social contacts (Guidon et al. Citation2019). Research highlighting the importance of social networks reveals that, beyond material considerations, mobility decisions are also motivated by social and affective factors, or a desire to feel ‘at home’ at the new place of residence.

At the macro level, studies show how economic determinants influence location choice. In economics we identify two distinct utility maximisation approaches: one with a focus on monetary aspects, and one that includes non-monetary aspects (Sirgy, Grzeskowiak, and Su Citation2005). Utility maximisation theory stipulates that individuals tend to find an ideal trade-off between housing and commuting costs, expressed in monetary terms (Alonso Citation1964). Monetary aspects include housing costs and rent, but also tax levels (Schmidheiny and Slotwinski Citation2018). Non-monetary elements may include group-segregation or pollution exposure (Banzhaf and Walsh Citation2013; Depro, Timmins, and O’Neil Citation2015; Liebe, Preisendörfer, and Meyerhoff Citation2010). Individuals can ‘vote with their feet’, deciding where to live by balancing taxes and access to local services such as public libraries, health services or education (Dowding, John, and Mergoupis Citation2002).

Political science and migration studies emphasise various factors at the macro level when describing places but, to our knowledge, these have not been directly related to individual location choice at the local (rather than national) level (e.g. McAuliffe and Jayasuriya Citation2016; Batista and McKenzie Citation2021). For instance, the literature recognises different ‘philosophies’ of national integration models (Brubaker Citation1992; Koopmans and Statham Citation2000; Pfirter et al. Citation2021). Most of this literature focuses on the effects of integration and citizenship policies, and research has expanded to consider variation at the subnational regional level, including cities and municipalities (Caponio and Borkert Citation2010; Hepburn Citation2011; Manatschal, Wisthaler, and Zuber Citation2020; Paquet Citation2014). These studies show that subnational integration policies can shape behaviour and attitudes of immigrants, such as their political engagement (Cinalli and Giugni Citation2011; Filindra and Manatschal Citation2020) or naturalisation intentions (Bennour Citation2020; Politi et al. Citation2021).

Here, we build on the literature on local policy variation and combine it with established considerations of location choice. We identified only two studies with a similar concern for the influence of the political context on immigrants’ location choice. Both show that elections or referendums won by far-right parties may greatly reduce mobility of foreign citizens to municipalities in Italy (Bracco et al. Citation2018) and Switzerland (Slotwinski and Stutzer Citation2019). In both contexts, hostile majority attitudes to immigrants act as a deterring factor for migrants, who thus choose different locations at a higher rate. While both studies demonstrate that political factors play a role in location choice, they employ a narrow approach to capturing the broader political reception context, and do not address the question of whether these political factors still matter when other well-established factors are accounted for. To do so, we adopt an encompassing view on the political reception context and examine how it influences location choice among recently arrived immigrants in Switzerland. More specifically, we refer to the ‘context of reception’ (Portes and Rumbaut Citation2006) to distinguish between attitudes of the native population in a specific place (societal discrimination) and government policy (i.e. integration and citizenship policies).

While there is a broad literature on attitudes to immigrants (see Pettigrew Citation2016; Rétiová et al. Citation2021 for reviews), we are concerned with the effects of these attitudes on immigrants and their sense of belonging (Simonsen Citation2016, Citation2018). Thinking about contexts of reception, the attitudes of residents can be more or less welcoming of immigrants and can signal legitimacy to foreign citizens who perceive themselves as members of the host society (Maxwell Citation2010). While attitudes may be expressed in many ways, drawing on recent studies (Bracco et al. Citation2018; Slotwinski and Stutzer Citation2019), we argue that votes for the radical right are a visible and public indicator of such attitudes. We expect that immigrants prefer municipalities with less electoral support for the radical right.

Regarding integration policies that regulate the political rights of immigrants and naturalisation policies, these policies can enhance the material and symbolic resources of foreign citizens (Bloemraad Citation2013). These resources can also make a municipality more attractive for immigrants, making them feel welcome on arrival (Van Hook, Brown, and Bean Citation2006). In the present paper, we study the Swiss case whose policies exhibit local variance (Helbling and Kriesi Citation2004; Probst et al. Citation2019): some cantons and municipalities allow foreign citizens to vote while others do not (Cattacin and Bülent Citation2001). When they are exposed to inclusive subnational integration policies, immigrants develop a stronger attachment to the host country, a stronger sense of belonging, and a greater intention to naturalise (Simonsen Citation2016; Bennour and Manatschal Citation2019; Bennour Citation2020). Accordingly, we expect that immigrants prefer places with inclusive integration policies that facilitate access to political participation via voting rights for foreign citizens.

To our knowledge, no study analysed the effects of naturalisation requirements on immigrants’ location choice, although we know that around 66% of recently arrived immigrants wish to naturalise in the future (nccr – on the move Citation2020). Following the same rationale as for voting rights and natives’ attitudes, we expect that fewer years of residence requirement for naturalisation are more attractive for immigrants to choose a future location than a longer required period of residence. As regards the generalisation of the findings, it is important to mention at this point that the conclusions of this study are limited to immigrants, who possess the information on political factors at their future context of residence.

Based on the theoretical reflections in this section, we clearly expect that an inclusive political reception context should increase the attractiveness of municipalities to recent immigrants. However, we consider it unlikely that all individuals are similarly responsive to the effects of political reception contexts on location choice (Lymperopoulou Citation2013). We explore whether certain characteristics, such as the social integration of immigrants or their socioeconomic status, are systematically associated with differences across the models. Given the exploratory character of these investigations, we refrained from formulating specific hypotheses. Instead, we discuss these associations with the hope of sparking future work in this direction.

Data and methods

Our research concerns the location choice of recent immigrants. We focus on immigrants because they have less attachment to their place of residence relative to the general population who have lived in a place for longer. This allows for a better understanding of whether political factors can lead to ‘voting with their feet’. Since time spent in a place reduces the desire to be mobile (Lewicka Citation2011), we restrict our analyses to immigrants who arrived in Switzerland within the preceding 15 years. They have had limited time to create strong roots in the local community, which, in turn, reduces immobility. At the same time, members in this group have already been in direct contact with the Swiss and subnational political reception context. We focus on Switzerland because of its federalist structure, which provides us with important subnational heterogeneity regarding integration and citizenship policies.

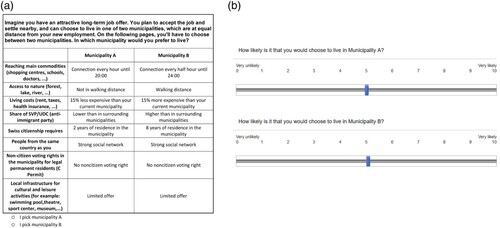

We use a conjoint experiment where participants repeatedly choose between two municipalities. Each municipality is assigned eight attributes (), which are all based on factors outlined in the literature: public transportation, access to nature, living costs, attitudes towards immigration, naturalisation requirements, presence of a co-ethnic community, voting rights for foreign citizens, and cultural and leisure infrastructures. Each attribute can have two randomly assigned levels – attractive or deterring – as a feature of the municipality. In total, there are 256 unique municipality profiles. In the analysis, we show the coefficients for the attractive features. For instance, for public transport, a ‘connection every half hour until midnight’ is considered more appealing than ‘a connection every hour until 20:00’. Similarly, we consider the following attributes as more attractive: being within walking distance to nature, a municipality being 15% less expensive than the current one, a lower share of anti-immigrant party voting than in the surroundings, needing less time before applying for citizenship (2 versus 8 years), the ability to vote after a year of residence, and a rich offer of cultural and leisure activities. Only attributes-levels were randomly assigned, whereas we did not randomise the order of characteristics. Research suggests that the latter does not influence respondents’ choices, unless the conjoint is very complex, which is not the case here (Auspurg and Jäckle Citation2017, 525)

Table 1. List of municipality attributes in the conjoint experiment, and the two possible values for each attribute.

In total, 1596 recent immigrants participated in our conjoint experiment.Footnote1 The experiment was conducted in six different languages (English, German, French, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese), which also allows us to include non-language-assimilated immigrants in our study. A conjoint experiment is ideal for testing how different meso- and macrofactors influence the location choice of recent immigrants as it allowing researchers to ‘estimate causal effects of multiple treatment components and assess several causal hypotheses simultaneously’ (Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto Citation2014, 1). We have taken care to present realistic choices to participants to simulate real-world possibilities, while the conjoint method helps to reduce different biases found in regular surveys, such as social desirability (Horiuchi, Markovich, and Yamamoto Citation2020; Wallander Citation2009).

We asked participants to imagine that they receive an attractive job offer, and to choose between two municipalities, equidistant from work, in which they would prefer to settle. We repeated this question five times, with each containing a forced choice (, Panel A) even if the chosen option does not have a perfect profile. This results in the outcome variable of interest (0 = not chosen municipality, 1 = chosen municipality, i.e. the response to ‘I pick municipality A/B’ in ). Participants are also asked to rank their likelihood of choosing one of the two municipalities, from 0 (very unlikely) to 10 (very likely) (, Panel B). This scale question provides a robustness check to our main models.

Figure 1. Example of conjoint experiment with forced choice shown to participants (bottom of Panel A): ‘I pick municipality A’, ‘I pick municipality B’;and the 0–10 scale shown to participants (Panel B).

For the exploratory analyses, we had the opportunity to link the participants of our conjoint experiment to the Migration-Mobility Survey (MMS) 2020. Also conducted in the same six languages as the conjoint experiment, the MMS is based on a representative sample of individuals who have moved to Switzerland in the preceding 15 years. In total, 7393 respondents (41% response rate) answered by telephone or via a webpage. The participants all are between 20 and 64 years old and emigrated to Switzerland after being 18 years old. The MMS includes questions on demographics, socioeconomic variables, migratory history, citizenship, education and labour market integration. With this broad set of variables, we can explore individual characteristics of the immigrants that may shape the extent to which they are influenced by the political reception context. The data collection took place between October 2020 and February 2021.

All recent immigrants in the sample of the conjoint experiment were born abroad; 49.4% are men and 50.6% women, and 50.6% of the respondents are EU nationals. As is to be expected with a sample of recently arrived immigrants in Switzerland (Wanner Citation2014), the sample is highly educated: 71.4% of the sample has a tertiary education. This means that the sample is not representative of the entire foreign-born population in Switzerland, which was not the aim of this study. To compare our sample to the general immigrant population of Switzerland, in the Appendix displays a comparison of main sociodemographic variables for which official data are available. To run our models, we use version 4.1.1 of R with the cjoint (Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto Citation2014) and cregg (Leeper Citation2020) packages. This allows us to identify average marginal component effects (AMCE) which express the causal effect of each attribute on individual location choice. AMCE maintains all components equal and shows how a change in an attribute’s level affects individual preferences.

Findings: political factors influence location choice

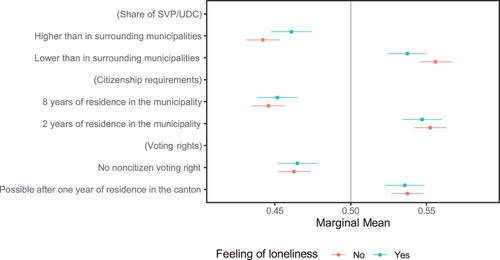

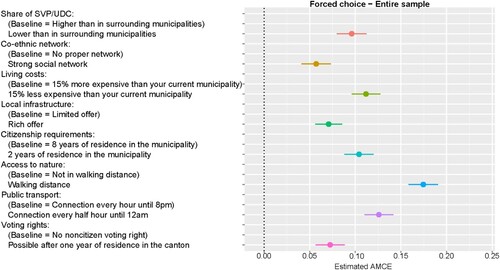

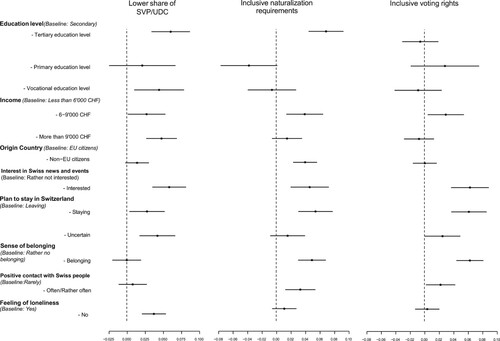

The model in demonstrates how the political reception context influences the location choice of recent immigrants. This is the case for all variables that capture the reception context. For instance, lower naturalisation requirements increase the attractiveness of a municipality compared to a place with stricter conditions: a reduction of six years before applying for naturalisation raises the probability of choosing a locality by 10.4 percentage points. The attitudes of the native population also explain the location choice of immigrants: relative to a locality with a higher anti-immigrant vote share than in the surroundings, a municipality with a lower far-right party share is 9.6 percentage points more attractive for recent immigrants. The right to vote in the canton after one year increases the chance of choosing a municipality by 7.2 percentage points compared to a place without voting rights.

Figure 2. Choosing a municipality, average marginal component effects (AMCE). Notes: Lines correspond to 95% the confidence interval of the change the probability to choose a municipality with a given attribute (estimated ACME). Outcome variable is picking a municipality with these attributes, conjoint experiment with forced choice, Switzerland 2020–2021. N = 1596 recent immigrants, 7980 choices. Choices are clustered by participants.

Non-political variables are also associated with the location choice of recent immigrants: a locality within walking distance to nature is 17.4 percentage points more likely to be chosen than a location without walkable access to nature. Because the data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is possible that this value is higher than it would otherwise have been, though a qualitative study carried out before the pandemic suggests that access to nature was highly valued by Swiss residents at that time as well (Efionayi-Mäder et al. Citation2020). A municipality with more regular public transport connections is favoured by 12.6 percentage points compared to less frequent connections. Respondents are 11.5 percentage points more likely to choose a location with 15% more buying power in comparison with a place that reduces their buying power by 15%. Also, a rich offer in cultural and leisure activities, as well as a strong social network of co-ethnics, make a municipality more attractive.

As a robustness check, we run the same model with scales as outcomes ( in the Appendix). Contrary to the forced choice, the scale allows for equal preferences, as well as, distinguishing between strong and weak preferences. These analyses confirm the relevance of the political reception context in explaining immigrants’ location choice, as immigrants tend to favour municipalities with an inclusive political reception context.

Exploratory analyses: the role of socioeconomic variables, legal status and social integration

In the following section, we explore whether the importance of the political reception context for location choice varies by immigrant characteristics. We base these subgroup analyses on immigrants’ resources and human capital, as these factors have been shown to be decisive for immigrants’ attitudes and behaviour. We did not develop a strong theoretical case and refrain from doing so post-hoc, but include these exploratory analyses to spark future investigation.

We examine socioeconomic variables, legal status and social integration. Individuals with high educational credentials or a high monthly household income may value the political reception context differently from individuals with low education levels or incomes. What is more, non-EU immigrants have a less stable political status, which may mean that they value access to more political rights differently from EU citizens. Regarding the degree of social integration (e.g. interest in Swiss news and events, feeling of belonging to Swiss society, intention to remain in Switzerland), we expect that these may also lead to differentiated evaluations of the political context for the location choice of immigrants. Related to this point, social networks may also moderate the influence of political factors on residential location choice.Footnote2

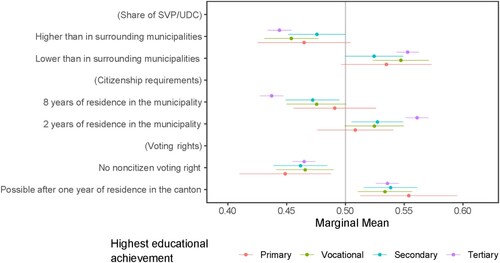

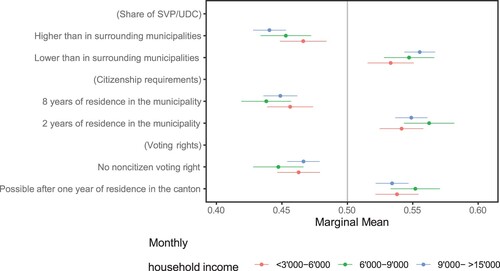

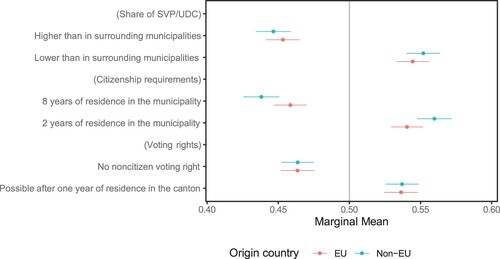

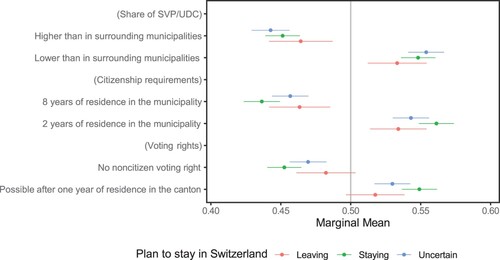

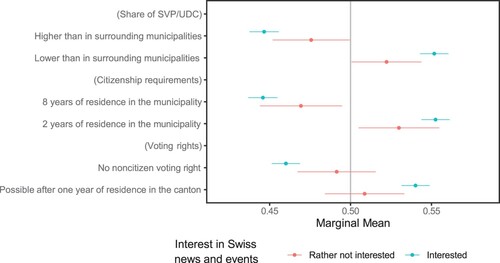

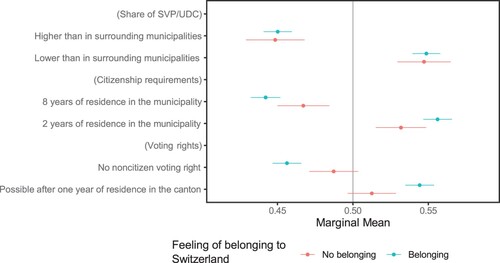

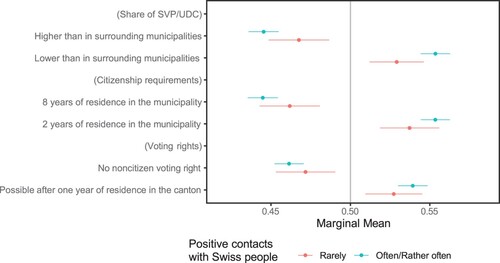

Political factors shape the location choice of immigrants for most subcategories considered. in the Appendix shows that voting rights influence location choice across all subgroups of educational attainment. By contrast, the attitudes of natives only affect the location choice of individuals with tertiary and vocational diplomas. Immigrants with tertiary and secondary educational achievements are also the only group influenced by naturalisation requirements for their residential choice. Regarding income and country of origin, and in the Appendix show that all subcategories are significantly influenced by every component of the political reception context. to in the Appendix further demonstrate that naturalisation requirements and native attitudes matter for all immigrants, irrespective of their interest in Swiss news, plans to stay in Switzerland or feeling of belonging to the host country. By contrast, voting rights do not seem to influence the location choice of those uninterested in Swiss news, who plan to leave the country or who do not feel they belong to Switzerland. Finally, and in the Appendix show that social integration influences all subcategories in terms of positive contacts with the local population and feelings of loneliness. In sum, we find that the influence of the political reception context is not necessarily homogeneous across subcategories.

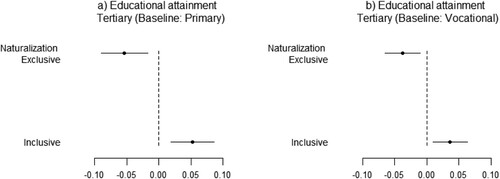

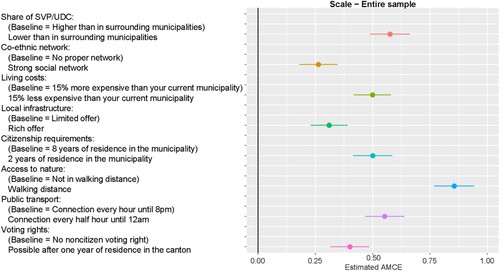

To ensure differences between subgroups are not biased by the reference category of each attribute, we follow the analytic strategy by Leeper, Hobolt, and Tilley (Citation2020). As proposed by the latter research, we change our analytical strategy as regards the difference in preferences among subgroups. Thus, we do not apply the AMCE and its difference across subgroups because this estimation would be misleading by only indicating a difference in effect size rather than a difference in preference. Therefore, we calculate the difference in marginal means between the subgroups with a 95% confidence interval, also known as a ‘nested model comparison’. These models tell us if statistically significant differences exist among subgroups regarding the influence of the political reception context. In addition, these estimates allow us to compare the differences of marginal means within a single attribute – e.g. exclusive naturalisation policy – across subgroups. shows that significant differences exist between subgroups with respect to the impact of the political context on location choice.

Figure 3. Difference in marginal means for subgroups depending on educational attainment, country of origin, income, links to Switzerland and social networks. Notes: Lines correspond to 95% confidence interval. Outcome variable is picking a municipality with these attributes, conjoint experiment with forced choice, Switzerland 2020–2021. N = 1.596 recent immigrants, 7.980 choices. Choices are clustered by participants. Insignificant findings were not included in but are discussed at the end of the empirical section and concern following variables: age, being a parent, gender, relationship status, time spent in Switzerland and residence permit.

demonstrates that individuals with tertiary education are more likely than those with a secondary education (baseline)to favour municipalities where natives’ attitudes and naturalisation requirements are inclusive. We find no substantial difference between individuals with a primary and a secondary diploma with regard to the influence of the political reception context. Individuals with a vocational diploma tend to favour more municipalities displaying inclusive natives’ attitudes than their counterparts having a secondary diploma.

Similar differences exist between individuals with tertiary education and immigrants with a primary and vocational education ( in the Appendix).

A different pattern appears in relating to monthly household income. Compared to the poorest immigrants (i.e. earning less than CHF 6000 a month), noncitizens with medium wage tend to favour municipalities displaying inclusive naturalisation requirements and voting rights. Also, the richest, earning more than CHF 9000 a month, show a preference for location with inclusive natives’ attitudes, compared to the baseline. also shows that recent immigrants coming from a non-EU country are much more influenced by citizenship policies than EU citizens. Non-EU citizens prefer more inclusive citizenship policies (i.e. 2 years of requirement) than EU citizens.

also shows that interest in news/events in Switzerland moderates the influence of political factors on immigrants’ location choice. Compared to uninterested immigrants, individuals interested in Swiss news tend to prefer inclusive political contexts. This holds true with regard to inclusive attitudes of natives, voting rights and naturalisation requirements. People with long-term projects in Switzerland favour a more inclusive political context than their counterparts who plan to leave Switzerland, irrespective of the measure used (naturalisation requirements, voting rights). Individuals who are uncertain about their future in Switzerland still prefer municipalities with inclusive natives’ attitudes than immigrants considering leaving the country. A sense of belonging is associated with greater preference for the most inclusive policy pole for a future location, regarding both naturalisation requirements and voting rights. The same two factors also positively influence the choice of individuals who have often/rather often positive contacts with Swiss people, compared to immigrants rarely enjoying such contact. We also show that feeling lonely moderates the influence of attitudes on the location choice of recent immigrants. Individuals who do not feel lonely seem to prioritise locations with a lower far-right share.

In addition, we also built an omnibus test to assess ‘group differences in preferences’ as proposed by Leeper, Hobolt, and Tilley (Citation2020, 220). This test allows us to assess whether a model accounting for subgroup differences better fits the data than a model using only conjoint features as predictors. As shown in (in the Appendix), the F-test statistics for all subcategory variables are statistically significant, supporting our assumption of varying treatment effects for the various subgroups.

At the same time, the exploration of subgroups also yielded ‘non-findings’, which we report here for the sake of transparency: gender, being a parent, relationship status (single or in a relationship), and age do not influence how immigrants react to the political context of reception. Rather surprisingly, time spent in Switzerland only marginally influences recent immigrants. This insignificant finding may reflect the rather small variation of time spent in Switzerland within our sample of recently arrived immigrants. Neither residence permits nor the experience of discrimination influence how political factors affect location choice.

Discussion and conclusion

Using a conjoint experiment with recent immigrants in Switzerland, we show that the political reception context shapes location choice, even when well established macrofactors, like economic differences, are taken into consideration. With this, we complement existing studies on location choice that focus on specific factors and neglect the relevance of the political context. While some studies suggest that political factors are important for the choice of destination country (Bracco et al. Citation2018), and political factors certainly play a role for asylum seekers in search of political stability (Collier Citation2013), here we demonstrate that the political context also matters for the internal mobility preferences of recent migrants. This shows that individuals could indeed ‘vote with their feet’ for political reasons, and not only for economic reasons or other ‘quality of life’ or lifestyle factors related to the infrastructure, cultural offer or closeness to nature of a given place (Florida Citation2004).

The exploratory analyses across subgroups show that recent immigrants react differently to the political reception context depending on various characteristics. We included this exploration both to understand patterns of immigrant integration and to spark future research on location choice. For instance, we provide experimental substantiation for Florida’s assertion in his work on the ‘creative class’(Citation2004), showing that highly educated individuals favour inclusive political reception contexts, but we also show that income does not seem to play a role in defining this creative class or its location choice. We also note that coming from an EU country moderates the influence of naturalisation policies on location choice. This finding is in line with Peters, Vink, and Schmeets (Citation2016), for instance, who show that non-EU nationals are more inclined to naturalise than EU nationals and, by implication, are more influenced by the inclusiveness of local citizenship regimes.

In the exploratory analysis, we reveal a high level of social integration: An emotional attachment to the host country is associated with a preference for an inclusive political reception context (Simonsen Citation2016). This may reflect the fact that immigrants with stronger links to Switzerland may also prefer to stay in Switzerland for a longer period of time (De Haas and Fokkema, Citation2011), but could also indicate homophily in the sense that immigrants who emotionally invest in the country of destination seek an environment where this is appreciated. Social networks also moderate the political reception context, notably in terms of attitudes towards immigration. Individuals who have friends and positive contact with Swiss people prefer places where the native population have more inclusive attitudes to immigration.

While we paint a rich picture on how the effects of the political reception context vary by subgroup, overall, we find that immigrants with the most capital – human or social – are those most influenced by the political reception context. Therefore, a possible interpretation is that the most privileged among immigrants can ‘afford’ to care more about the inclusiveness of the political reception context. This finding resonates with the work of Putnam, Leonardi, and Nanetti (Citation1993) suggesting that social and human capital are relevant to explaining civic engagement and political participation. Thus, municipalities displaying an inclusive political reception context may be more noticeably attractive for immigrants with important human and social capital. The only exception we can find here relates to non-EU citizens who are less privileged than EU nationals, in terms of stability of stay and entry rights. This difference in legal rights helps to emphasise the point that location choice also plays a functional role, as suggested by studies on economic determinants, but one that includes the political sphere.

In terms of our aim of sparking new research, we think, for example, of the need to consider different aspects of the political reception context. For instance, we can imagine that our findings would be different had we included language courses rather than voting rights, especially since language courses are relevant to only part of the immigrant population. We suggest that this study could possibly be replicated in other contexts that exhibit variation in integration policies and citizenship regulation, whether due to regional differences within federal countries or for other reasons. We strongly suggest that the sample be broadened to the entire immigrant population of the host country, beyond newly arrived immigrants. While we argue that the focus on recently arrived immigrants has distinct advantages, location choice by established immigrants with strong local networks may follow different logics. Our findings about mobility intentions corroborate earlier studies on behavioural outcomes, which show that immigrants avoid moving to a xenophobic municipality (Bracco et al. Citation2018; Slotwinski and Stutzer Citation2019). Taken together, this evidence suggests that immigrants are aware of the political reception context at their future place of residence. Future research is needed to test this assumption, and to learn more about the factors driving individual mobility decisions.

In conclusion, we urge future research on immigrant mobility to consider the role that political factors may have. In this way, we believe that research on human mobility will be better placed to inform the allocation of local resources to successfully plan for infrastructure and amenities, including public transport. In the meanwhile, the finding that inclusive places attract immigrants with a deeper attachment to the host country highlights how negative attitudes to immigration, and support for radical right-wing parties, are a barrier to the social integration of immigrants, perversely undermining the very outcome that some members of society so vehemently demand of their immigrant communities.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank A. Wuffle for encouragement. Author contributions: SB, AM, DR designed the study; SB analysed the data; SB, DR, AM wrote the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data from the conjoint experiment will be made available on Zenodo on publication; data from the survey are available on request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The study was pre-registered at https://aspredicted.org/blind.php?x=jx56us.

2 The variables we use for this exploration are shaped by their availability in the MMS. Education is categorical (Tertiary education: 71.4%; Secondary: 11.6%; Primary: 5%; Vocational: 12%). Immigrants from a non-EU country represent 49.4% of the sample (50.6% are EU nationals). Monthly income is measured at the household level: less than CHF 3000 to 6000: 25.7%; CHF 6000 to 9000: 22.9%, CHF 9000 and more: 51.4%. Subjective attachment to Switzerland is measured using three variables: The first is derived from asking ‘On a scale from 0 (‘not at all’) to 7 (‘to a very high extent’), to what extent are you interested in news and current events in Switzerland’. We combine response values 0–3 into a single category (‘rather uninterested’, 11.6% of the sample), with the remainder classified as ‘interested’. The second variable asks about plans to settle in Switzerland, differentiating between ‘plan to leave’ (15.3%), ‘plan to stay’ (45.8%), and ‘uncertain’ (38.9%). The third variable asks: ‘To what extent do you agree with the following statements: ‘Globally, I feel myself belonging to Swiss society’’. We combine the two disagreement options into ‘no belonging’ (23.8% of the sample) and the remainder into ‘belonging’. To capture social networks, we ask: ‘How often do you have you positive contacts with Swiss people?’, with ‘never’ and ‘from time to time’ combined into ‘rarely’ (21.4% of the sample), and the remainder into ‘often/very often’ (78.6%). Together, subjective attachment to Switzerland and immigrants’ social networks provide a measure social integration. A binary variable captures feelings of loneliness (59.2% do not feel lonely).

References

- Aassve, A., G. Betti, S. Mazzuco, and L. Mencarini. 2007. “Marital Disruption and Economic Well-Being: A Comparative Analysis.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 170 (3): 781–799.

- Alonso, W. 1964. Location and Land Use. Toward a General Theory of Land Rent.

- Arrighi, J.-T., and L. Piccoli. 2018. SWISSCIT: Index on Citizenship Law in Swiss Cantons. Neuchâtel: nccr – on the move.

- Auspurg, K., and A. Jäckle. 2017. “First Equals Most Important? Order Effects in Vignette Based Measurement.” Sociological Methods & Research 46 (3): 490–539. doi:10.1177/0049124115591016.

- Banzhaf, H. S., and R. P. Walsh. 2013. “Segregation and Tiebout Sorting: The Link Between Place-Based Investments and Neighborhood Tipping.” Journal of Urban Economics 74: 83–98. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2012.09.006.

- Batista, C., and D. McKenzie. 2021. Testing Classic Theories of Migration in the Lab. IZA Discussion Paper 14717:1–49.

- Bennour, S. 2020. “Intention to Become a Citizen: Do Subnational Integration Policies Have an Influence? Empirical Evidence from Swiss Cantons.” Regional Studies 54 (11): 1535–1545.

- Bennour, S., and A. Manatschal. 2019. “Immigrants' Feelings of Attachment to Switzerland: Does the Cantonal Context Matter?” In Migrants and Expats: The Swiss Migration and Mobility Nexus, edited by I. Steiner, and P. Wanner, 189–220. Cham: Springer.

- Bhat, C. R., and J. Y. Guo. 2006. Comprehensive Analysis of Built Environment Characteristics on Household Residential Choice and Automobile Ownership Levels (No. 06-0990).

- Bloemraad, I. 2006. “Citizenship Lessons From the Past: The Contours of Immigrant Naturalization in the Early 20th Century.” Social Science Quarterly 87 (5): 927–953.

- Bloemraad, I. 2013. “The Great Concern of Government: Public Policy as Material and Symbolic Resources.” In Outsiders No More? Models of Immigrant Political Incorporation, edited by J. Hochschild, J. Chattopadhyay, C. Gay, and M. Jones-Correa, 195–208. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Borjas, G. J. 1999. “Immigration and Welfare Magnets.” Journal of Labor Economics 17 (4): 607–637.

- Bracco, E., M. De Paola, C. P. Green, and V. Scoppa. 2018. “The Effect of Far Right Parties on the Location Choice of Immigrants: Evidence from Lega Nord Mayors.” Journal of Public Economics 166: 12–26.

- Brubaker, R. 1992. Citizenship and Nationhood in France and Germany. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Cao, X., P. L. Mokhtarian, and S. L. Handy. 2009. “Examining the Impacts of Residential Self-Selection on Travel Behaviour: A Focus on Empirical Findings.” Transport Reviews 29 (3): 359–395.

- Caponio, T., and M. Borkert. 2010. The Local Dimension of Migration Policymaking. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Cattacin, S., and K. Bülent. 2001. Le Développement des Mesures D’intégration de la Population Migrante sur le Plan Local en Suisse. Forum Suisse Pour L’étude des Migrations. Neuchâtel: University of Neuchâtel.

- Cinalli, M., and M. Giugni. 2011. “Institutional Opportunities, Discursive Opportunities and the Political Participation of Migrants in European Cities.” In Social Capital, Political Participation and Migration in Europe, edited by L. Morales, and M. Giugni, 43–62. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Collier, P. 2013. Exodus: How Migration is Changing Our World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Colwell, P. F., C. A. Dehring, and G. K. Turnbull. 2002. “Recreation Demand and Residential Location.” Journal of urban economics 51 (3): 418–428.

- Damm, A. P. 2009. “Ethnic Enclaves and Immigrant Labor Market Outcomes: Quasi-Experimental Evidence.” Journal of Labor Economics 27 (2): 281–314.

- De Haas, H., and T. Fokkema. 2011. “The Effects of Integration and Transnational Ties on International Return Migration Intentions.” Demographic Research 25: 755–782.

- Depro, B., C. Timmins, and M. O’Neil. 2015. “White Flight and Coming to the Nuisance: Can Residential Mobility Explain Environmental Injustice?” Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists 2 (3): 439–468. doi:10.1086/682716.

- Dieleman, F. M. 2001. “Modelling Residential Mobility; A Review of Recent Trends in Research.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 16 (3): 249–265.

- Dowding, K., P. John, and T. Mergoupis. 2002. Fiscal Mobility in Metropolitan England.

- Efionayi-Mäder, D., J. Fehlmann, J. Probst, D. Ruedin, and G. D’Amato. 2020. Mit- und Nebeneinander in Schweizer Gemeinden – Wie Migration von der Ansässigen Bevölkerung Wahrgenommen Wird. Bern: Eidgenössische Migrationskommission EKM.

- Ermisch, J. F., and S. P. Jenkins. 1999. “Retirement and Housing Adjustment in Later Life: Evidence from the British Household Panel Survey.” Labour Economics 6 (2): 311–333.

- Ersanilli, E., and R. Koopmans. 2011. “Do Immigrant Integration Policies Matter? A Three-Country Comparison Among Turkish Immigrants.” West European Politics 34 (2): 208–234. doi:10.1080/01402382.2011.546568.

- Ersanilli, E., and S. Saharso. 2011. “The Settlement Country and Ethnic Identification of Children of Turkish Immigrants in Germany, France, and the Netherlands: What Role do National Integration Policies Play?” International Migration Review 45 (4): 907–937. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7379.2011.00872.x.

- Federal Statistical Office. 2021. Les élections au Conseil national: Force des partis dans le canton (le canton=100%) – 1971–2019 | Tableau. Federal Statistical Office. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/fr/home/statistiques/catalogues-banques-donnees/tableaux.assetdetail.11048442.html.

- Filindra, A., and A. Manatschal. 2020. “Coping with a Changing Integration Policy Context: American State Policies and Their Effects on Immigrant Political Engagement.” Regional Studies 54 (11): 1546–1557.

- Florida, R. 2002. The Rise of the Creative Class. New York: Basic books.

- Goodman, S. W., and M. Wright. 2015. “Does Mandatory Integration Matter? Effects of Civic Requirements on Immigrant Socio-Economic and Political Outcomes.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (12): 1885–1908.

- Guidon, S., M. Wicki, T. Bernauer, and K. Axhausen. 2019. “The Social Aspect of Residential Location Choice: On the Trade-Off Between Proximity to Social Contacts and Commuting.” Journal of Transport Geography 74: 333–340.

- Hainmueller, J., and D. Hangartner. 2013. “Who Gets a Swiss Passport? A Natural Experiment in Immigrant Discrimination.” American Political Science Review 107 (1): 159–187.

- Hainmueller, J., D. J. Hopkins, and T. Yamamoto. 2014. “Causal Inference in Conjoint Analysis: Understanding Multidimensional Choices Via Stated Preference Experiments.” Political Analysis 22 (1): 1–30.

- Helbling, M. 2008. Practising Citizenship and Heterogeneous Nationhood: Naturalisations in Swiss Municipalities. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. doi:10.5117/9789089640345

- Helbling, M. 2010. “Switzerland: Contentious Citizenship Attribution in a Federal State.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36 (5): 793–809. doi:10.1080/13691831003764334.

- Helbling, M., and H. Kriesi. 2004. “Staatsbürgerverständnis und Politische Mobilisierung: Einbürgerungen in Schweizer Gemeinden.” Swiss Political Science Review 10 (4): 33–58.

- Hepburn, E. 2011. “Citizens of the Region: Party Conceptions of Regional Citizenship and Immigrant Integration.” European Journal of Political Research 50 (4): 504–529.

- Horiuchi, Y., Z. D. Markovich, and T. Yamamoto. 2020. “Does Conjoint Analysis Mitigate Social Desirability Bias?” MIT Political Science Department Research Paper No. 2018-15.

- Kaplan, R., and M. E. Austin. 2004. “Out in the Country: Sprawl and the Quest for Nature Nearby.” Landscape and Urban Planning 69 (2–3): 235–243.

- Koopmans, R. 2010. “Trade-Offs Between Equality and Difference: Immigrant Integration, Multiculturalism and the Welfare State in Cross-National Perspective.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36 (1): 1–26.

- Koopmans, R., and P. Statham. 2000. Challenging Immigration and Ethnic Relations Politics: Comparative European Perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Krizek, K. J., and P. Waddell. 2002. “Analysis of Lifestyle Choices: Neighborhood Type, Travel Patterns, and Activity Participation.” Transportation Research Record 1807 (1): 119–128.

- Lee, E. S. 1966. “A Theory of Migration.” Demography 3 (1): 47–57.

- Leeper, T. J. 2020. cregg: Simple Conjoint Analyses and Visualization. R package version 0.4.0.

- Leeper, T. J., S. B. Hobolt, and J. Tilley. 2020. “Measuring Subgroup Preferences in Conjoint Experiments.” Political Analysis 28 (2): 207–221.

- Lewicka, M. 2011. “Place Attachment: How Far Have We Come in the Last 40 Years?” Journal of Environmental Psychology 31 (3): 207–230.

- Liebe, U., P. Preisendörfer, and J. Meyerhoff. 2010. “To Pay or Not to Pay: Competing Theories to Explain Individuals’ Willingness to Pay for Public Environmental Goods.” Environment and Behavior 43 (1): 106–130. doi:10.1177/0013916509346229.

- Lymperopoulou, K. 2013. “The Area Determinants of the Location Choices of New Immigrants in England.” Environment and Planning A 45 (3): 575–592.

- Manatschal, A. 2011. “Taking Cantonal Variations of Integration Policy Seriously – Or How to Validate International Concepts at the Subnational Comparative Level.” Swiss Political Science Review 17 (3): 336–357.

- Manatschal, A., V. Wisthaler, and C. I. Zuber. 2020. “Making Regional Citizens? The Political Drivers and Effects of Subnational Immigrant Integration Policies in Europe and North America.” Regional Studies 54 (11): 1475–1485. doi:10.1080/00343404.2020.1808882.

- Maxwell, R. 2010. “Evaluating Migrant Integration: Political Attitudes Across Generations in Europe.” International Migration Review 44 (1): 25–52.

- McAuliffe, M., and D. Jayasuriya. 2016. “Do Asylum Seekers and Refugees Choose Destination Countries? Evidence from Large-Scale Surveys in Australia, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.” International Migration 54 (4): 44–59.

- McAuliffe, M., B. Khadria, and C. Bauloz. 2019. World Migration Report 2020. Geneva: IOM.

- Montgomery, M., and C. Curtis. 2006. Housing Mobility and Location Choice: A Review of the Literature (Working Paper No. 2). Perth: Curtin University of Technology. http://urbanet.curtin.edu.au/local/pdf/ARC_TOD_Working_Paper_2.pdf.

- Mulder, C. H., and N. T. Lauster. 2010. “Housing and Family: An Introduction.” Housing Studies 25 (4): 433–440.

- Nccr– on the move. 2020. Migration-Mobility Survey. Neuchatel: nccr – on the move.

- Paquet, M. 2014. “The Federalization of Immigration and Integration in Canada.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 47 (10): 519–548.

- Permentier, M., G. Bolt, and M. Van Ham. 2011. “Determinants of Neighbourhood Satisfaction and Perception of Neighbourhood Reputation.” Urban Studies 48 (5): 977–996.

- Peters, F., M. Vink, and H. Schmeets. 2016. “The Ecology of Immigrant Naturalisation: A Life Course Approach in the Context of Institutional Conditions.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (3): 359–381.

- Pettigrew, T. F. 2016. “In Pursuit of Three Theories: Authoritarianism, Relative Deprivation, and Intergroup Contact.” Annual Review of Psychology 67: 1–21.

- Pfirter, L., L. S. Borrelli, D. Ruedin, and S. Kurt. 2021. “Citizenship Models and Migrant Integration – Rethinking the Intersection of Citizenship and Migrant Integration Through (b)Ordering.” In Handbook of Citizenship and Migration, edited by M. Giugni, and M. Grasso, 52–65. London: Edward Elgar.

- Politi, E., S. Bennour, A. Lüders, A. Manatschal, and E. G. Green. 2021. “Where and Why Immigrants Intend to Naturalize: The Interplay Between Acculturation Strategies and Integration Policies.” Political Psychology. doi:10.1111/pops.12771.

- Portes, A., and R. G. Rumbaut. 2006. Immigrant America: A Portrait. Oakland: Univ of California Press.

- Probst, J., G. D’Amato, S. Dunning, D. Efionayi-Mäder, J. Fehlmann, A. Perret, D. Ruedin, and I. Sille. 2019. Kantonale Spielräume im Wandel.SFM-Bericht. 73. Neuchâtel: Swiss Forum for Migration and Population Studies.

- Putnam, R. D., R. Leonardi, and R. Nanetti. 1993. Making Democracy Work. Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Rétiová, A., I. R. Božič, R. Klvaňová, and B. N. Jaworsky. 2021. “Shifting Categories, Changing Attitudes: A Boundary Work Approach in the Study of Attitudes Toward Migrants.” Sociology Compass 15 (3): e12855. doi:10.1111/soc4.12855.

- Sasser, A. C. 2010. “Voting with Their Feet: Relative Economic Conditions and State Migration Patterns.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 40 (2–3): 122–135.

- Schmidheiny, K., and M. Slotwinski. 2018. “Tax-Induced Mobility: Evidence from a Foreigners’ Tax Scheme in Switzerland.” Journal of Public Economics 167: 293–324.

- Scott, S., and P. Brindley. 2012. “New Geographies of Migrant Settlement in the UK.” Geography 97 (1): 29–38.

- Simonsen, K. B. 2016. “How the Host Nation’s Boundary Drawing Affects Immigrants’ Belonging.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (7): 1153–1176.

- Simonsen, K. B. 2018. “What It Means to (Not) Belong: A Case Study of How Boundary Perceptions Affect Second-Generation Immigrants’ Attachments to the Nation.” Sociological Forum 33 (1): 118–138. doi:10.1111/socf.12402.

- Sirgy, M. J., S. Grzeskowiak, and C. Su. 2005. “Explaining Housing Preference and Choice: The Role of Self-Congruity and Functional Congruity.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 20 (4): 329–347.

- Slotwinski, M., and A. Stutzer. 2019. “The Deterrent Effect of an Anti-Minaret Vote on Foreigners’ Location Choices.” Journal of Population Economics 32 (3): 1043–1095.

- Smith, B., and D. Olaru. 2013. “Lifecycle Stages and Residential Location Choice in the Presence of Latent Preference Heterogeneity.” Environment and Planning A 45 (10): 2495–2514.

- Ström, S. 2010. “Housing and First Births in Sweden, 1972–2005.” Housing Studies 25 (4): 509–526.

- Tiebout, C. M. 1956. “A Pure Theory of Local Expenditures.” Journal of Political Economy 64 (5): 416–424.

- Toussaint-Comeau, M., and S. L. Rhine. 2004. “The Relationship Between Hispanic Residential Location and Homeownership.” Economic Perspectives-Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago 28 (3): 2.

- van Heerden, S., and D. Ruedin. 2019. “How Attitudes Towards Immigrants Are Shaped by Residential Context: The Role of Neighbourhood Dynamics, Immigrant Visibility, and Areal Attachment.” Urban Studies 56 (2): 317–334. doi:10.1177/0042098017732692.

- Van Hook, J., S. K. Brown, and F. D. Bean. 2006. “For Love or Money? Welfare Reform and Immigrant Naturalization.” Social Forces 85 (2): 643–666. doi:10.1353/sof.2007.0029.

- Walker, J. L., and J. Li. 2007. “Latent Lifestyle Preferences and Household Location Decisions.” Journal of Geographical Systems 9 (1): 77–101.

- Wallander, L. 2009. “25 Years of Factorial Surveys in Sociology: A Review.” Social Science Research 38 (3): 505–520.

- Wanner, P. 2014. Une Suisse à 10 Millions D’habitants. Enjeux et Débats. Lausanne: Presses polytechniques et universitaires romandes.

- Zufferey, J., I. Steiner, and D. Ruedin. 2021. “The Many Forms of Multiple Migrations: Evidence from a Sequence Analysis in Switzerland, 1998 to 2008.” International Migration Review 55 (1): 254–279. doi:10.1177/0197918320914239.

Appendix

Figure A1. Robustness check with scale as outcome – AMCE – Entire sample – (95% confidence interval).

Figure A5. Marginal means depending on interest in Swiss news and events – (95% confidence interval).

Figure A7. Marginal means depending on the feeling of belonging to Switzerland – (95% confidence interval).

Figure A8. Marginal means depending on positive contacts with Swiss people – (95% confidence interval).

Table A1. Comparison of demographic variables between conjoint experiment sample and the entire immigrant population of Switzerland.

Table A2. Omnibus test across all subgroups.