ABSTRACT

In the last 20 years, several major terror attacks conducted in the name of political Islam hit Western Europe. We examine the impact of such terror attacks on hostile behaviour on social media from a cross-national perspective. To this end, we draw upon time-stamped, behavioural data from YouTube and focus on the frequency and popularity (‘likes’) of ethnically insulting comments among a corpus of approximately one hundred thousand comments. We study aggregate change and use individual-level panel data to investigate within-user change in ethnic insulting in periods leading up to and following major terror events in Germany, France and the UK. Results indicate that terror attacks boost interest in immigration-related topics in general, and lead to a disproportional increase in hate speech in particular. Moreover, we find that attack effects spill over to other countries in several, but not all, instances. Deeper analyses suggest, however, that this pattern is mainly driven by changes in the composition of users and not by changing behaviour of individual users. That is, a surge in ethnic insulting comes from hateful users newly entering online discussions, rather than previous users becoming more hateful following an attack.

Introduction

In recent years, Europe has witnessed a strong increase in immigration from Muslim-majority countries (Pew Research Center Citation2017). At the same time, a number of fatal terrorist attacks conducted in the name of political Islam have hit several European countries (see Helbling and Meierrieks Citation2020 for an overview). The combination of these two trends has led far-right activist groups (Schwemmer Citation2018) as well as some European politicians (e.g.: Kaminski Citation2015; Waterfield Citation2015) to frame immigration as a threat in terms of security as well as culture. Such political elite discourses have been associated with more hostile attitudes toward Muslim immigrants in Europe (Czymara Citation2020). In turn, perceived discrimination among Muslims in Europe increased after Islamist terror attacks (Giani and Merlino Citation2020). By fomenting social conflict and politicising tensions along ethno-cultural lines, terror attacks pose a threat to the cohesion of increasingly diverse societies beyond the devastating consequences for those immediately affected.

Existing evidence on the effect of terror events on migration attitudes is somewhat ambiguous. Several studies show more hostile attitudes after a terror attack (e.g. Hopkins Citation2010; Legewie Citation2013; Böhmelt, Bove, and Nussio Citation2019; Finseraas, Jakobsson, and Kotsadam Citation2011; Nussio, Bove, and Steele Citation2019) and suggest that the effects of terrorism on anti-immigrant attitudes in Europe diffuse across borders (Böhmelt, Bove, and Nussio Citation2019). However, other scholars reported little or no effect (e.g. Brouard, Vasilopoulos, and Foucault Citation2018; Finseraas, Jakobsson, and Kotsadam Citation2011; Larsen, Cutts, and Goodwin Citation2019). Moreover, there is research arguing that attitudes toward immigrants and other minorities are rather stable, or at least not easily affected by single events (Drouhot et al. Citation2023; Kiley and Vaisey Citation2020; Kustov, Laaker and Reller Citation2021). Other explanations for the absence of terrorism effect in some studies revolve around methodological concerns regarding the appropriateness of survey items to measure such effects (see Czymara and Schmidt-Catran Citation2017, 736). Survey data may be too coarse to measure the time sensitivity of the effect of terror events (see Legewie Citation2013) and is likely impacted by social desirability bias inherent to face-to-face or telephone interviews (see Piekut Citation2021). Meanwhile, the documented rise in hate crimes (Deloughery, King, and Asal Citation2012; Jäckle and König Citation2018; King and Sutton Citation2013; Byers and Jones Citation2007; Hanes and Machin Citation2014; Frey Citation2020; Jacobs and van Spanje Citation2020) and support for anti-immigrant parties (Jacobs and van Spanje Citation2021) in the wake of terror attacks indicate that such attacks do affect public sentiments and behaviour.

We contribute to this literature by testing how terror events trigger ethnically hostile behaviour in a setting that plays an increasingly important role in the life of many, but received little attention in the literature so far: social media. Namely, we examine whether terrorism boosts ethnic insulting on YouTube from a multi-national perspective. We analyse a large body of comments written in reaction to YouTube videos pertaining to immigration over a four-year period (beginning of 2014 to the end of 2017). In contrast to secondary survey data, such digital trace data capture naturally occurring behaviour – i.e., behaviour that is observed and recorded by researchers without interacting with respondents and, thus, without contaminating their behaviour in any way (Golder and Macy Citation2014). Our research design exploits the time-stamped, granular and behavioural nature of social media data (Drouhot et al. Citation2023; see also Kelling and Monroe Citation2023) in order to study two types of ethnically derogatory behaviour: (i) Posting and (ii) liking ethnically insulting comments. Our broader research question states: does ethnically insulting behavior on social media change in the aftermath of terrorist attacks? We draw upon a corpus of roughly 100,000 comments in three major countries of immigration in Europe – all of whom witnessed at least one major act of violence perpetrated in the name of Islam: France, Germany and the UK. Our four-year time span covers several such attacks in various countries, and thus allows us to examine how the impact of terrorism differs by country and attack.

Terror attacks, threat perceptions and out-group derogation

One of the most prominent explanations of negative attitudes toward ethnic minorities is the group threat-paradigm, which argues that such attitudes are the result of the perception that minority members pose a threat to the society’s majority group (for overviews see, e.g. Ceobanu and Escandell Citation2010; Dinesen and Hjorth Citation2020). In his classical paper, Blumer (Citation1958) defines significant events as a key aspect for the formation of ethnic prejudice because they shape a certain picture of the minority group. In particular, he argues that events ‘loaded with great collective significance’ are ‘particularly potent in shaping the sense of social position’ (Blumer Citation1958, 6). Such events can lead majority members to fear the loss of what they consider their traditional way of life or national cohesion. Terror attacks are certainly among such significant events. However, terrorist attacks do not only threaten values but are also a direct threat to individual or collective safety (Legewie Citation2013). Since threat perceptions are unambiguously associated with negative attitudes toward foreigners (Dinesen and Hjorth Citation2020), terror attacks should lead to more negative attitudes. Although research has shown that immigration does not lead to more terrorism in Western countries (Helbling and Meierrieks Citation2020), some individuals engage in ‘causal attribution’ of the negative consequences of terrorism to immigrants or specific ethnic minorities (Böhmelt, Bove, and Nussio Citation2019; Hewstones Citation1989). In addition, false generalisation due to emotional arousal (Sniderman et al. Citation2019), feelings of anxiety and anger (Vasilopoulos, Marcus, and Foucault Citation2018) or ‘simplified thinking’ (Jungkunz, Helbling, and Schwemmer Citation2018) might lead to spillover effects on attitudes toward ethnic minorities in general.

Various studies have examined the impact of terror attacks on immigration attitudes, often based on secondary survey data. Such studies draw upon the fact that, in some cases, large survey programmes were in the field during a terror attack. Many of these studies show that attitudes toward immigrants are more negative after a terror attack, although such effects vary in magnitude and significance across countries (Böhmelt, Bove, and Nussio Citation2019; Finseraas, Jakobsson, and Kotsadam Citation2011; Hopkins Citation2010; Legewie Citation2013; Nussio, Bove, and Steele Citation2019; Schmidt-Catran and Czymara Citation2020; Schüller Citation2016; but see Brouard, Vasilopoulos, and Foucault Citation2018; Castanho Silva Citation2018). Similarly, Kaakinen, Oksanen, and Räsänen (Citation2018) show that young Finns reported to be significantly more often exposed to online hate speech after the November 2015 Paris attacks. Schwemmer (Citation2018) finds that the Facebook page of the anti-immigrant PEGIDA movement in Germany radicalised after the sexual assaults in Cologne on New Year’s Eve 2015/2016. Increased exposure to hate speech also correlates with the perception that one’s society is characterised by fear (Oksanen et al. Citation2018). Such fears can go beyond borders, as several cross-national studies report that public opinion becomes more hostile after attacks also in countries where the attack did not happen (Böhmelt, Bove, and Nussio Citation2019; Jäckle and König Citation2018; Legewie Citation2013). Finseraas and Listhaug (Citation2013) even report that the murder of the Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh by a radical Islamist led to a preference for a more restrictive immigration policy in some European countries but, strikingly, not in the Netherlands. While it is reasonable to assume that a terror attack has the most impact where and when it happens, its influence on attitudes might not be strictly limited in time and space. First, terror effects disseminate over national borders (Böhmelt, Bove, and Nussio Citation2019). Second, effects of (seemingly related) terror attacks may be cumulatively reactivated with each new event (Czymara and Schmidt-Catran Citation2017, 739). Drawing upon these previous findings, we test for the impact of several terror attacks in various countries.

We focus on individual behaviour on social media. In particular, we analyse the effect of Islamist terror attacks on ethnic insulting in YouTube comments. We observe two types of derogatory behaviour: writing and liking ethnically insulting comments. Liking comments takes little time and is anonymous since only the total number of likes of a comment is visible. In contrast, posting a comment involves more time investment and the willingness to be potentially identifiable. While both actions are thus associated with different costs, the threat-paradigm predicts that people become more hostile after terror attacks, which should have an impact on both kinds of behaviour. Thus, we hypothesise that:

Hypothesis 1: The share of ethnically insulting comments on YouTube videos about migration issues increases following terrorist attacks. (Commenting-Hypothesis)

Hypothesis 2: The popularity of comments containing ethnic insults increases following terrorist attacks. (Liking-Hypothesis)

Hypothesis 3a: Individual commenters post more ethnically insulting comments following a terror attack. (Behavioural Change-Hypothesis)

Hypothesis 3b: New commenters, who post more ethnically insulting comments, enter the comment sections following a terror attack. (Compositional Change-Hypothesis)

Analysed terror attacks

We focus on the impact of the six largest Islamist terrorist attacks that happened between January 2015 and December 2017 in Europe. All triggered public shocks, and were highly salient in the media in the three countries we study. These attacks are summarised in .

Table 1. Overview of terrorist attacks included in the analyse.

Several studies report that effects of these attacks on various forms of out-group related attitudes or feelings. This includes the Charlie Hebdo (Vasilopoulos, Marcus, and Foucault Citation2018) and Bataclan attacks (Jungkunz, Helbling, and Schwemmer Citation2018; Kaakinen, Oksanen, and Räsänen Citation2018; Nussio, Bove, and Steele Citation2019), or the Berlin Christmas market truck attack (Fischer-Preßler, Schwemmer, and Fischbach Citation2019; Nägel and Lutter Citation2020; Schmidt-Catran and Czymara Citation2020). Note, however, that there are also studies that do not find effects of the 2015 or the 2016 Paris attacks (Brouard, Vasilopoulos, and Foucault Citation2018; Castanho Silva Citation2018). We draw upon this body of literature and extend it by, first, analysing behavioural data instead of self-reported attitudes in surveys and, second, comparing the effects of different attacks in different countries. While we have at least one attack happening in each of the three countries under investigation, half of our analysed attacks happened in France (see ). We also have one attack that happened in a country we do not include in our analysis (Belgium, see endnote 2). This allows us to separate the impact of attacks, first, based on their temporal order and, second, by differentiating domestic attacks from those in other European countries.

Measuring ethnic insulting in YouTube commentsFootnote1, Footnote2

Our analysis relies on text comments on YouTube videos pertaining to immigration in France, Germany and the UK. Social media have often been deemed particularly potent to boost extreme opinions, as online environments encourage the formation of echo chambers and thereby lead to a higher willingness to express hate – especially in online places where anonymity is stronger (Alvarez and Winter Citation2020 Kaakinen, Oksanen, and Räsänen Citation2018;). At the same time by not being limited to time and space, social media platforms facilitate the interactions between groups with differing (and potentially clashing) ideological views, out of which conflicts may arise (Erjavec and Kovačič Citation2012). Hence, we regard YouTube as a strategic research site to answer our research question.

To ensure sufficient number of videos as well as comments before and after the terrorist attacks under study, we set the time frame for video upload dates between 1 January 2014 and 31 December 2017. YouTube has limited features, however, when it comes to filtering by time, and we, therefore, relied on Google for video searches. We used keywords for collecting on-topic videos, i.e. ‘migration’, ‘Islam’, ‘Muslim’, ‘refugees’, ‘terrorism’, ‘salafism’, ‘jihad’, ‘AND’ ‘discussion [country]’ in either French, German or English depending on the language of the video.Footnote3 shows the five most frequent (translated) terms in the titles of the videos within our analysed period (stop words removed). The results confirm that our search string primarily identified videos dealing with Islam, refugees and related topics and are, thus, relevant to our research question. While most videos received a limited number of comments, some videos act as rallying points that attract many commenters – including hateful ones – after a terror attack, as we show in online Appendix D.

Table 2. Most frequent terms in titles of analysed videos (n = total number of videos).

We retrieved all available comments from each video using the VosonSML package (Graham et al. Citation2020) and corresponding information on video title, view counts and comment likes using the tuber package (Sood Citation2019). To classify comments as ethnic insults, we employed the Perspective API of Google Jigsaw’s Conversation AI using Votta's (Citation2020) peRspective package. The Perspective API ‘is trained to recognize a variety of attributes (e.g. whether a comment is toxic, threatening, insulting, off-topic, etc.) using millions of examples gathered from several online platforms and reviewed by human annotators’ (Google Citation2021a). While the details of its classification approach remain proprietary, Perspective is based on convolutional neural networks (Dixon et al. Citation2018; Google Citation2021b).Footnote4 As we are interested in ethnic insulting, we use Perspective’s IDENTITY_ATTACK attribute, which predicts the probability of a comment to be a ‘Negative or hateful [comment] targeting someone because of their identity’ (Google Citation2021a).Footnote5 We defined comments as ethnic insults when the API predicted a probability above 90 percent (as a robustness check, we also ran models with a 75 percent cutoff, leading to stronger effects in the same direction, which are available upon request). To validate the automated classification, we hand-coded a random sample of comments in each language (DE: n = 1,731; FR: n = 1,555; UK: n = 638). Based on these hand-coded comments, it becomes evident that ethnic insulting is in fact very rare in our data: the share of ethnically insulting comments ranges from 2.7 percent in the French data to 5.4 percent in the German and 6.3 percent in the UK data, respectively. The machine-based classifier had precision scores of about 0.5 for French and English (which are most of the analysed data), meaning that roughly half of the predicted insults are in line with the hand-coded data, but only 0.2 for German. Recall ranges from 0.7 for Germany to 0.3 for the UK, meaning that the algorithm detected one to two thirds of the hand-coded insults. Lower cutoff values (e.g. 75 percent) increased recall but reduced precision, which is more important for our purpose as insults in our data are very rare. Put differently, the larger cutoff value of 90 percent can be regarded as a rather conservative measure of ethnic insulting.

While the overlap of predicted and hand-coded insults is not perfect, our main interest lies in changes of ethnic insulting after attacks. Our analyses rest on the assumption that such measurement error remains constant over time. We consider this assumption generally reasonable, and test it on a new set of 100 hand-coded comments in each language for the Berlin Christmas market attack (50:50 before and after). Results show that the error rate in classifying comments as ethnically insulting is largely similar before and after the attack (see Table B1 in online Appendix B). Hence, while the estimates are likely to be noisy, it is unlikely that they are systematically biased by our classification strategy. As an alternative approach,Footnote6 we used a dictionary-based strategy similar to Spörlein and Schlueter (Citation2020). Unfortunately, this approach yielded precision scores below 0.25 for all countries in our data, so we opted against using such dictionaries. While the effects are less stable, we reach substantively similar results with such a dictionary-based classifier. We report these results as robustness checks in online Appendix C.

Based on the classified comments, we constructed user- and comment-level datasets spanning a three-week window before and after the attacks in Paris (Charlie Hebdo [January 2015] and the Bataclan [November 2015]), Brussels (March 2016), Nice (July 2016), Berlin (December 2016) and Manchester (May 2017). Though the three-week time window is a somewhat arbitrary cutoff, it is reasonable considering that the attacks gained ample attention and remained a hot topic for weeks in the media. Overall, the specified period resulted in 102,396 comments, out of which 7265 are classified as ethnically insulting.

Analytical strategy

First, we investigate whether the share of ethnically insulting comments increases after terrorist attacks. We run linear probability models regressing a dummy variable indicating whether a comment contains an ethnic insult on a variable capturing whether the comment was made in the three-week window before or after a given attack. In a second step, we look at the popularity of insulting comments before and after the attacks. We run linear regression models regressing the number of a comment’s likesFootnote7 on an interaction term between the insult dummy and the time variable (again three weeks before or after each attack). We employ robust standard errors to correct for overdispersion in like counts.Footnote8 We estimate all models for the pooled sample as well as for each attack separately.

Methodologically, terror events can be treated as natural experiments – i.e. they cannot be anticipated by users who may in turn be influenced by them. As such, estimates for their causal effects do not need control variables under the assumption that observations analysed before and after the event do not systematically differ, and that no other time trend or simultaneous event act as potential confounders (Legewie Citation2013; Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno, and Hernández Citation2020, 189–191). However, this first assumption may be violated in case of systematic compositional change in the population of users (for instance towards more hostile commenters) in the period following the attacks. In a final step, we, therefore, test our third set of hypotheses focusing on within-user change in commenting behaviour. We create a balanced panel dataset consisting of users who commented at least once within a three-week window before and after the same terrorist event. In particular, we aggregate the data by creating a variable that counts ethnically insulting comments in the three weeks before and after an attack, resulting in a user panel of two time periods for each attack. While the results from these analyses are specific to frequent users who commented at least once before and after the attack, they allow us to gauge the effect of terrorist events on the number of posted insulting comments for each user over time. Put differently, user-level fixed-effects examine the changes in commenting within each user, adjusting for any unobservable, time-invariant characteristics of users.

The impact of terror attacks on posting ethnically insulting comments on YouTube

Descriptive results

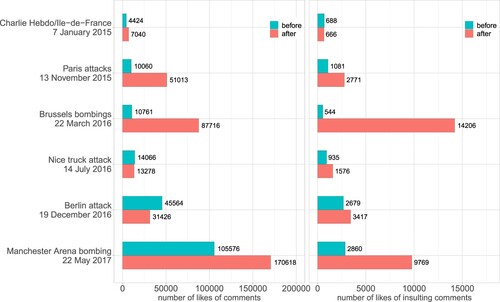

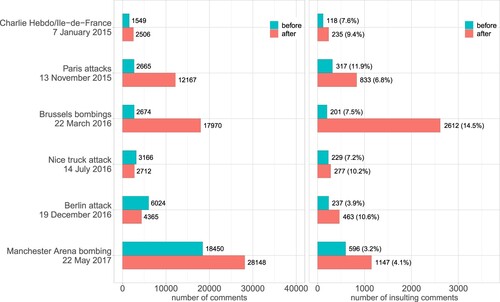

We first analyse changes in comments in relation to the terrorist attacks. displays the overall number of comments (left panel) and the number of ethnically insulting comments (right panel) in the three weeks prior to and following the terrorist attacks for the sample pooled across all countries. Looking at the left panel in , we see a boost in commenting activity after four out of six attacks. In particular, the total number of comments increased sharply after the Brussel bombings (by a factor of almost seven) and, to a lesser degree, after the Paris attacks and Manchester Arena bombing. The Charlie Hebdo shootings triggered only a minor rise in comments, whereas the opposite pattern held for the Nice and Berlin attacks. With respect to the insulting nature of the comments, we see a more uniform, upward tendency. The sheer number of insulting comments increased after all six attacks (right panel of ). This increase is most pronounced for the Brussel bombings, where the total number of insulting comments rose by a factor of more than 12 (from 201 to 2612), followed by the Paris attacks and the Manchester Arena bombing. Several of the insults after the attacks are targeted at Muslims, with most having a clear xenophobic message and a harsh tone.Footnote9 For example, after the Brussels attack one user in the UK data wrote ‘[…] islam is a murderous death cult!’. After the Charlie Hebdo attack, a comment from the UK data reads ‘fuck pisslam!!!! allmost all muslims are terorrist but they can't do anything because they are soooooooooooooooooo backward and stupid, they're powerless. fuck pisslam!!’; and a comment from the French data ‘they killed 11?? we will kill 1111!! those bastards with their animal religion’. Similarly, a German user wrote after the Berlin attack ‘fuck off from the german reich’. These examples illuminate that the derogatory nature of the ethnically insulting comments in our data after attacks.

Figure 1. Overall number of comments and number of insulting comments before and after attacks. Percentages in parentheses show the relative number of insulting comments to overall number of comments.

Compared to the overall rise in commenting, the share of insulting comments increased after five out of six attacks. While the proportion of comments that contain an ethnic insult is slightly higher after the Charlie Hebdo, Nice and Manchester attacks, it increases up to seven percentage points in the case of Brussels and Berlin. Interestingly, the share of insulting comments after the Paris attacks dropped by five percentage points, which is due to the large increase in the overall number of comments that followed.

Regression models

The descriptive findings from are largely supported by the results obtained from linear probability models. Overall, we find that attacks have a combined positive effect on the probability of a comment to contain ethnic insults (β = 0.03, SE = 0.00, two-sided p-value <0.001). Furthermore, examining the effects of attacks separately reveals that the chance of a comment to contain ethnic insults increased significantly after four out of six attacks (). Consistent with the results from (right panel), the effects are found to be largest for the Brussels bombings and the Berlin attack, smallest for the Manchester Arena bombing and in between for the Nice truck attack. In contrast to what we see in , however, we do not find a statistically significant effect for the Charlie Hebdo shootings. Finally, the probability of insulting comments decreased after the Paris attacks, which again validates our previous observations from (right panel). Overall, the results point to a significant increase in the share of insulting comments after most (but not all) attacks and provide partial support for our Commenting-Hypothesis.

Figure 2. Linear probability models predicting change in probability of a comment to contain ethnic insults (Charlie Hebdo/Ile-de-France, Nobs = 4055; Paris attacks, Nobs = 14,832; Brussels bombings, Nobs = 20,644; Nice truck attack, Nobs = 5878; Berlin attack, Nobs = 10,389; Manchester Arena bombing, Nobs = 46,598).

Alternative approaches analysing the insulting comments in weekly intervals provide consistent results (Figure A1 in online Appendix A). These analyses reveal that the effects of most attacks peak after some days after they occur. In addition, we find elevated levels of insulting activity in one week before the Charlie Hebdo and Berlin attacks, and in two weeks before the Manchester Arena bombing. While these swings might have been caused by some events other than the attacks per se, given the collection of our videos we expect the effects of such unobserved events to be present both before and after the attacks.

Results from supplementary models using country-specific samples show that the effects of terror attacks are dependent on the national context (see Figures A2–A4 in online Appendix A). Specifically, the aggregate effects we found for the Nice, Berlin and Manchester attacks were present in Germany and France, but not in the UK. Conversely, the Paris attacks displayed a negative effect on the probability of insulting comments only in the UK but not in other countries. Finally, in contrast to the results shown in , the Brussels bombings did not have a significant impact in any of the three countries, but the Charlie Hebdo shootings show a significant positive effect in the UK. Taken together, these results offer partial support for the argument that terrorism can have effects outside national borders (cf. Böhmelt, Bove, and Nussio Citation2019).

The impact of terror attacks on liking ethnically insulting comments on YouTube

Descriptive results

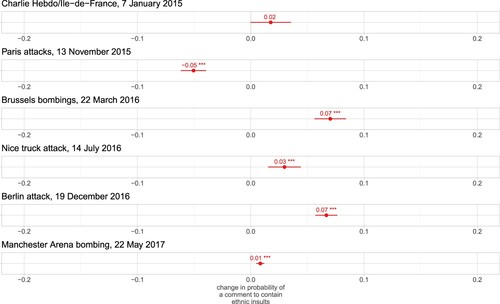

Having examined the changes in insulting comments in the three weeks before and after the attacks, we now turn to the changes in popularity of insulting comments in the same time period. shows counts of likes of overall comments (left panel) and counts of likes of insulting comments (right panel) for the sample pooled across all countries. The overall patterns we see in are substantially mirrored in . In particular, we see in the left panel that the absolute number of positive ratings given to all types of comments increased most drastically after the Brussel bombings and the Manchester Arena bombing, and to a lesser degree after the Paris attacks. For other attacks, the change was only marginal (the Charlie Hebdo shootings), and even in the opposite direction (the Nice and Berlin attacks). A similar picture emerges with respect to the total number of likes given to all insulting comments in our data. Two exceptions are the Nice and Berlin attacks after which the number of likes of insulting comments increased despite a drop in the number of likes given to comments in general.

Regression models

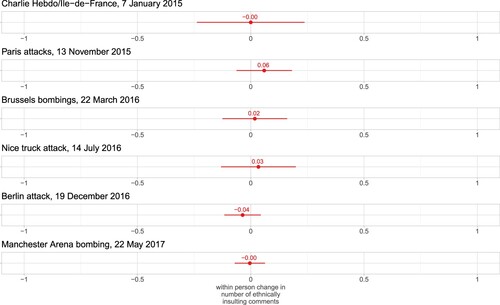

The results shown in point to an increase in the popularity of insulting comments among users after the attacks. However, we know from that the overall number of ethnically insulting comments increased after most terror attacks. Thus, the total increase in the number of likes of insulting comments might be due to the increase in insulting comments. Indeed, once we consider the changes in likes at the comment level, we find no substantial increase in the number of likes that single insulting comments received. An OLS model predicting the count of likes reveals that an insulting comment in our sample received on average 5.5 likes before the attacks. This did not change significantly after the attacks (β = 0.90, SE = 0.95, two-sided p-value > 0.05). This null finding is bolstered by the results from the attack-specific analyses shown in ; the point estimates are negative in three cases and not statistically different from zero for any of the six attacks. Alternative approaches analysing the likes of comments in weekly intervals or focusing on country-specific samples provide similar results (Figures A5–A8 in online Appendix A). The only exception is a positive effect of the Manchester Arena bombing on the liking of insulting comments in the UK. Overall, our results suggest that most terrorist attacks did not have a sizable impact on the like counts of insulting comments. We thus find no support for the Liking-Hypothesis.

Figure 4. OLS models predicting change in number of likes in single ethnically insulting comments (Charlie Hebdo/Ile-de-France, Nobs = 4055; Paris attacks, Nobs = 14,832; Brussels bombings, Nobs = 20,644; Nice truck attack, Nobs = 5878; Berlin attack, Nobs = 10,389; Manchester Arena bombing, Nobs = 46,598).

Examining intra-individual change in behaviour: user fixed effects models

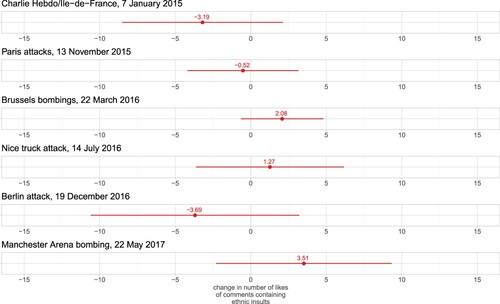

As reported above, we find that ethnic insulting increases following terrorist attacks for four out of six attacks. However, up until now we have only examined aggregate trends, from which we cannot infer that individuals changed their behaviour and started to insult more. To examine this, we analyse user fixed-effects models based on individual-level panel data. This allows us to compare users’ commenting behaviour before and after attacks but, of course, only for those who commented before and after.

shows the predicted probabilities of ethnic insulting before and after each attack, calculated from linear regression models with user fixed effects. The estimates are roughly zero for all attacks, suggesting no evidence for a within-person change towards more frequent insulting. Additional analyses indicate that, generally, most users who comment before a terror attack do not comment after an attack, which renders a general statement on within-user change complicated. Nevertheless, these findings suggest that the increase in total number of insulting comments is most likely due to new users entering the discussion following terror events rather than a within-person change in insulting behaviour. The results of the user FE models refute the Behavioural Change-Hypothesis and support the Compositional Change-Hypothesis.

Figure 5. Linear models with user fixed-effects predicting the within-person change in the number of ethnic insults before and after each attack (Charlie Hebdo/Ile-de-France, Nobs = 156; Paris attacks, Nobs = 472; Brussels bombings, Nobs = 334; Nice truck attack, Nobs = 236; Berlin attack, Nobs = 500; Manchester Arena bombing, Nobs = 992).

Conclusion: how terror events shapes public debates on social media

Based on a large body of comments on immigration-themed YouTube videos, we examined whether major Islamist terrorist attacks increase ethnically insulting behaviour. Our results reveal that the absolute number of insulting comments tends to increase after an attack. Importantly, this increase even outperforms the growth of general (i.e. non-insulting) commenting after a terror attack in four out of six cases. This implies that a given person is likely to encounter an ethnic insult after an attack when scrolling through a subset of the comments for these attacks. This result is largely stable to different modelling choices and mirrors other natural experimental studies that report more negative attitudes in survey data after such attacks (Hopkins Citation2010; Legewie Citation2013; Nussio, Bove, and Steele Citation2019), including spillover effects to other countries (Böhmelt, Bove, and Nussio Citation2019). However, we do not find a similar result when it comes to liking ethnically insulting comments after terror attacks, which might be an artefact of our measurement strategy, as we address below.

Importantly, we do not replicate the effect of terrorism on posting ethnically insulting videos in our fixed-effects models of highly active users. Although one should be cautious with generalisations based on this rather specific subsample, this indicates that observed discursive shifts at the aggregate level after terror attacks are less driven by changing behaviour among individual users than a change in the composition of the population of users. In other words, typical commenters do not seem to become more hateful after attacks, while hateful users join the discussion and thus alter the aggregate trends. This mirrors other research on racist and anti-immigrant behaviour on social media: Flores (Citation2017) and Spörlein and Schlueter (Citation2020) come to a similar conclusion using American Twitter data and German YouTube comments, respectively. A possible explanation is that hateful commenters have no interest in real discussions. Hence, they might often comment once on each video and then move on to the next. While our design was not tailored to follow individual users throughout the website, future research might want to test this explanation more thoroughly.

One limitation of our study regards the generalisability of our findings. Our results are based on a rather specific subset of YouTube users and not the general public (Mellon and Prosser Citation2017). Although we are not aware of existing studies on YouTube commenters specifically, systematic bias in the population of users is plausible, e.g. regarding education or age. Second, we only analyse a fraction of YouTube videos, but debates in the comment section probably depend on the content and tone of the video itself. While we have no reason to assume that our selection of comments is systematically biased and our dataset contained videos with a clear anti-immigration tone, analysing, for example, videos specifically aimed at immigration sceptics might offer additional insights. In light of previous research, the effect of terror events might be heterogeneous and dependent on prior hostile attitudes (Spörlein and Schlueter Citation2020; Alvarez and Winter Citation2020). Third, we used timestamps of comments to measure the timing of likes as YouTube does not provide any information on the latter. Unfortunately, the default ordering of comments in YouTube is not only by date but by ‘Top comments’, which rely on multiple parameters such as recency and ratings of a comment, number of replies to that comment, and previous ratings of the user who posted it. For these ‘top comments’, there could be considerable inconsistencies between the timing of comments and timing of likes. This might have undermined the quality of our proxy for the timing of likes and, ultimately, driven the null results for likes. Likewise, comments flagged by other users (such as that containing ethnic insults) may receive less exposure to likes, which may again play a role in our null result.Footnote10 A fourth limitation is that YouTube actively purges its platform of hateful content, and it is, therefore, possible that some of the insulting comments were removed from the site before we started collecting data. However, our analysed period ends in June 2017, whereas YouTube took down the vast majority of videos and comments from April 2018 onwards (Google Citation2020). Hence, we assume that this had no big impact on our data (also see Spörlein and Schlueter Citation2020). Fifth, we know little on how much behaviour on YouTube, or social media in general, mirrors offline behaviour or personal chats. Finally, the amount of data rendered manual coding of all comments infeasible, calling for machine-driven approaches to identify ethnic insults. However, several machine-learning classifiers and a predefined dictionary largely failed at identifying hateful comments. Even Google’s Perspective API, which might be regarded as the spearhead of machine-learning approaches, did not perform very well when compared to a subset of hand-coded comments. This is because automated classification of insults specifically related to ethnicity seems very difficult for existing approaches. Given the development of such tools is advancing rapidly, future research is likely to have access to finer detection strategies, and thus be even more successful in this respect.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our empirical approach showcases several important benefits compared to survey data when it comes to the study of intergroup conflict (Drouhot et al. Citation2021). First, terror attacks during fieldwork periods of surveys are mere coincidence. While this is beneficial from the perspective of identifying causal effects, it severely limits available cases. In contrast, social media data has become available at virtually all time points and periods for much of the world’s population, allowing testing effects of any future event with high granularity (Flores Citation2017). Second, anonymous social media behaviour is presumably less plagued by social desirability bias which the presence of an interviewer might induce for sensitive topics such as racial prejudice (Piekut Citation2021). As digital trace data, social media data are ‘found data’ generated by users themselves and are not subject to the artificial setting and restrictions imposed by a researcher (such as an answering scale in a survey). Third, most survey research on terror attacks relies on secondary survey data, and is thereby forced to analyse items that were not designed to capture specific attitudes, such as security concerns or views of particular ethnic groups (Czymara and Schmidt-Catran Citation2017). Unless large surveys such as the European Social Survey permanently maintain a rich set of items measuring intergroup attitudes, it remains difficult to measure the potential effect of exogenous shocks such as terror events if their effects are circumscribed to specific groups. In that regard, digital trace data containing texts offer promising approach to study in situ change in enmity targeted at specific minorities (see Kelling and Monroe Citation2023 for an application of ‘text-as-data’ approach to study municipal-level reaction to refugees).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (1.6 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Code for all analyses is made available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/MXNCQ. In accordance with YouTube’s API policies, we are not allowed to share our scraped YouTube data.

Notes

1 We thank Pamina Noack, Theodora Benesch, Jannik Track, and Margherita Cusmano for helpful research assistance as well as Paul Statham and the JEMS reviewers for insightful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. We also thank the Volkswagen Foundation, Emanuel Deutschmann, Jan Lorenz and other organizers of the BIGSSS-Computational Social Science Summer School on Migration for bringing us all together in Sardinia in June 2019. Direct correspondence to Lucas G. Drouhot, [email protected].

2 We did all data preprocessing and analysis in R. Code is available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/MXNCQ.

3 While we include an attack that took place in Belgium in our analyses, we did not query for videos by adding a ‘discussion Belgium’ search string. We added the attack in Belgium because it was particularly deadly and to study potential diffusion across national borders documented in prior work (Böhmelt, Bove, and Nussio Citation2019; Jäckle and König Citation2018). Second, we used multiple computers for our YouTube searches and different day times (but same search string and location). We cannot be certain that this did not affect our search, though any effect on the results should be negligible.

4 We thank Thomas R. Davidson for pointing this out.

5 Perspective offers various other attributes such as TOXICITY or INSULT (Google Citation2021a). However, these attributes also include attacks on the individual and, thus, miss the group-specific component of our concept ‘ethnic insult’. While someone’s ‘identity’ might not be identical to their ethnic or racial identity in all cases, we assume a strong overlap in our data as we sampled videos specifically on immigration issues. Thus, we see IDENTITY_ATTACK as the best proxy for ethnic insulting.

6 As yet an alternative approach, we trained three Support Vector Machines (SVM) based on 75 percent of each language’s hand-coded sample as training data. Unfortunately, the SVM was not able to identify any of the insulting comments in the remaining validation data for UK and France, and merely twelve percent of insults in the German data (similar problems for other data splits and K-Nearest Neighbor or Random Forest models). Hence, while SVM is more conservative on false positives, the fact that it yields recall and precision of 0 for two of our three countries unfortunately renders this approach inadequate for our purpose.

7 We focus merely on likes because dislike ratings, unfortunately, are not included in the YouTube meta-data. In addition, the metadata lacks information on the timing of likes. Therefore, we use the time variable computed in the first step (based on timestamps for comments) as a proxy for the timing of likes.

8 We also ran negative binomial regression models which are usually considered a good fit for count data. Results from these models were similar to the results we obtained from OLS. We decided to present the results from OLS as it allows for an easier interpretation of the interaction coefficients, which are our primary interest.

9 In the quoted examples, we translate all comments to English, but we do not correct mistakes.

10 A flagged status should not theoretically affect our ability to register it in our classification strategy; however the current version of the VosonSML package does not allow for the analysis of flagged comments specifically (Graham et al. Citation2020).

References

- Alvarez, Amalia, and Fabian Winter. 2020. “The Breakdown of Anti-Racist Norms: A Natural Experiment on Normative Uncertainty After Terrorist Attacks.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (37): 22800–22804.

- Blumer, Herbert. 1958. “Race Prejudice as a Sense of Group Position.” The Pacific Sociological Review 1 (1): 3–7.

- Böhmelt, Tobias, Vincenzo Bove, and Enzo Nussio. 2019. “Can Terrorism Abroad Influence Migration Attitudes at Home?” American Journal of Political Science 00 (0): 1–15.

- Brouard, Sylvain, Pavlos Vasilopoulos, and Martial Foucault. 2018. “How Terrorism Affects Political Attitudes: France in the Aftermath of the 2015–2016 Attacks.” West European Politics 41 (5): 1073–1099.

- Byers, Bryan D., and James A. Jones. 2007. “The Impact of the Terrorist Attacks of 9/11 on Anti-Islamic Hate Crime.” Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice 5: 43–56.

- Castanho Silva, Bruno. 2018. “The (Non)Impact of the 2015 Paris Terrorist Attacks on Political Attitudes.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 44 (6): 838–850.

- Ceobanu, Alin M., and Xavier Escandell. 2010. “Comparative Analyses of Public Attitudes Toward Immigrants and Immigration Using Multinational Survey Data: A Review of Theories and Research.” Annual Review of Sociology 36 (1): 309–328.

- Czymara, Christian S. 2020. “Propagated Preferences? Political Elite Discourses and Europeans’ Openness Toward Muslim Immigrants.” International Migration Review 54 (4): 1212–1237.

- Czymara, Christian S., and Alexander W. Schmidt-Catran. 2017. “Refugees Unwelcome? Changes in the Public Acceptance of Immigrants and Refugees in Germany in the Course of Europe’s ‘Immigration Crisis.” European Sociological Review 33 (6): 735–751.

- Deloughery, Kathleen, Ryan D. King, and Victor Asal. 2012. “Close Cousins or Distant Relatives? The Relationship Between Terrorism and Hate Crime.” Crime & Delinquency 58 (5): 663–688.

- Dinesen, Peter Thisted, and Frederik Hjorth. 2020. “Attitudes toward Immigration: Theories, Settings, and Approaches.” In The Oxford Handbook of Behavioral Political Science, edited by Alex Mintz; Lesley G. Terris, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dixon, Lucas, John Li, Jeffrey Sorensen, Nithum Thain, and Lucy Vasserman. 2018. “Measuring and Mitigating Unintended Bias in Text Classification.” In Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society.

- Drouhot, Lucas G., Emanuel Deutschmann, V. Carolina Zuccotti, and Emilio Zagheni. 2023. “Computational Approaches to Migration and Integration Research: Promises and Challenges”. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (2): 389–407. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2022.2100542.

- Drouhot, Lucas G., Sören Petermann, Karen Schönwälder, and Steven Vertovec. 2021. “Has the Covid 19, Pandemic Undermined Public Support for a Diverse Society? Evidence from a Natural Experiment in Germany.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 44(5): 877–892.

- Erjavec, Karmen, and Melita Poler Kovačič. 2012. “You Don't Understand, This is a New War! Analysis of Hate Speech in News Web Sites’ Comments.” Mass Communication and Society 15 (6): 899–920.

- Finseraas, Henning, Niklas Jakobsson, and Andreas Kotsadam. 2011. “Did the Murder of Theo van Gogh Change Europeans’ Immigration Policy Preferences?” Kyklos 64 (3): 396–409.

- Finseraas, Henning, and Ola Listhaug. 2013. “It Can Happen Here: The Impact of the Mumbai Terror Attacks on Public Opinion in Western Europe.” Public Choice 156 (1–2): 213–228.

- Fischer-Preßler, Diana, Carsten Schwemmer, and Kai Fischbach. 2019. “Collective Sense-Making in Times of Crisis: Connecting Terror Management Theory with Twitter User Reactions to the Berlin Terrorist Attack.” Computers in Human Behavior 100: 138–151.

- Flores, René D. 2017. “Do Anti-Immigrant Laws Shape Public Sentiment? A Study of Arizona’s SB 1070 Using Twitter Data.” American Journal of Sociology 123 (2): 333–384.

- Frey, Arun. 2020. “‘Cologne Changed Everything’ - The Effect of Threatening Events on the Frequency and Distribution of Intergroup Conflict in Germany.” European Sociological Review 36 (5): 1–16.

- Giani, Marco, and Luca Paolo Merlino. 2020. “Terrorist Attacks and Minority Perceived Discrimination.” The British Journal of Sociology 72: 1468–4446.12799.

- Golder, Scott A., and Michael W. Macy. 2014. “Digital Footprints: Opportunities and Challenges for Online Social Research.” Annual Review of Sociology 40 (1): 129–152. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043145.

- Google. 2020. “Transparency Report”. Retrieved April 2021. https://transparencyreport.google.com/youtubepolicy/removals?content_by_flag=period:Y2018Q2;exclude_automated:&lu=content_by_flag.

- Google. 2021a. “About the API”. https://support.perspectiveapi.com/s/about-the-api.

- Google. 2021b. “Best Practices & Risks”. https://support.perspectiveapi.com/s/about-the-api-best-practices-risks.

- Graham, Timothy, Ackland, Robert, Chan, Chung-hong and Bryan Gertzel. 2020. “vosonSML: Collecting Social Media Data and Generating Networks for Analysis.” R package version 0.29.10. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vosonSML.

- Hanes, Emma, and Stephen Machin. 2014. “Hate Crime in the Wake of Terror Attacks: Evidence from 7/7 and 9/11.” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 30: 247–267.

- Helbling, Marc, and Daniel Meierrieks. 2020. “Terrorism and Migration: An Overview.” British Journal of Political Science 52: 977–996.

- Hewstones, Miles. 1989. Causal Attribution: From Cognitive Processes to Collective Beliefs. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Hopkins, Daniel J. 2010. “Politicized Places: Explaining Where and When Immigrants Provoke Local Opposition.” American Political Science Review 104 (1): 40–60.

- Jäckle, Sebastian, and Pascal D. König. 2018. “Threatening Events and Anti-Refugee Violence: An Empirical Analysis in the Wake of the Refugee Crisis during the Years 2015 and 2016 in Germany.” European Sociological Review, 34 (6): 728–743.

- Jacobs, Laura, and Joost van Spanje. 2020. “A Time-Series Analysis of Contextual-Level Effects on Hate Crime in The Netherlands.” Social Forces 100 (1): 169–193.

- Jacobs, Laura, and Joost van Spanje. 2021. “Not All Terror Is Alike: How Right-Wing Extremist and Islamist Terror Threat Affect Anti-Immigration Party Support.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 33 (4): 737–755.

- Jungkunz, Sebastian, Marc Helbling, and Carsten Schwemmer. 2018. “Xenophobia Before and After the Paris 2015 Attacks: Evidence from a Natural Experiment.” Ethnicities 19 (2): 271–291.

- Kaakinen, Markus, Atte Oksanen, and Pekka Räsänen. 2018. “Did the Risk of Exposure to Online Hate Increase After the November 2015 Paris Attacks? A Group Relations Approach.” Computers in Human Behavior 78: 90–97.

- Kaminski, Matthew. 2015. “All the Terrorists Are Migrants”. https://www.Politico.Eu/Article/Viktor-Orban-Interview-Terrorists-Migrants-Eu-Russia-Putin-Borders-Schengen/.

- Kelling, Claire, and Burt Monroe. 2023. “Analyzing Community Reaction to Refugees Through Text Analysis of Social Media Data.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (2): 492–534. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2022.2100551.

- Kiley, Kevin, and Stephen Vaisey. 2020. “Measuring Stability and Change in Personal Culture Using Panel Data.” American Sociological Review 85 (3): 477–506.

- King, Ryan D., and Gretchen M. Sutton. 2013. “High Times for Hate Crimes: Explaining the Temporal Clustering of Hate-Motivated Offending.” Criminology; An Interdisciplinary Journal 51: 871–894.

- Kustov, Alexander, Dillon Laaker, and Cassidy Reller. 2021. “The Stability of Immigration Attitudes: Evidence and Implications.” Journal of Politics 83 (4): 1478–1494. doi:10.1086/715061.

- Larsen, Erik Gahner, David Cutts, and Matthew J. Goodwin. 2019. “Do Terrorist Attacks Feed Populist Eurosceptics? Evidence from Two Comparative Quasi-Experiments.” European Journal of Political Research 59 (1): 182–205.

- Legewie, Joscha. 2013. “Terrorist Events and Attitudes Toward Immigrants: A Natural Experiment.” American Journal of Sociology 118 (5): 1199–1245.

- Mellon, J., and C. Prosser. 2017. “Twitter and Facebook are not Representative of the General Population: Political Attitudes and Demographics of British Social Media Users.” Research & Politics 28: 186–206. doi:10.1017/pan.2019.27.

- Muñoz, Jordi, Albert Falcó-Gimeno, and Enrique Hernández. 2020. “Unexpected Events During Survey Design: Promises and Pitfalls for Causal Inference.” 28: 186–206.

- Nägel, Christof, and Mark Lutter. 2020. “The Christmas Market Attack in Berlin and Attitudes Toward Refugees: A Natural Experiment with Data from the European Social Survey.” European Journal for Security Research 5: 199–221.

- Nussio, Enzo, Vincenzo Bove, and Bridget Steele. 2019. “The Consequences of Terrorism on Migration Attitudes Across Europe.” Political Geography 75 (December 2018): 102047.

- Oksanen, Atte, Markus Kaakinen, Jaana Minkkinen, Pekka Räsänen, Bernard Enjolras, and Kari Steen-Johnsen. 2018. “Perceived Societal Fear and Cyberhate After the November 2015 Paris Terrorist Attacks.” Terrorism and Political Violence 6553 (November 2015): 1–20.

- Pew Research Center. 2017. Muslim population growth in Europe. Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. Accessed May 12, 2020. https://www.pewforum.org/2017/11/29/europes-growing-muslim-population/.

- Piekut, Aneta. 2021. “Survey Nonresponse in Attitudes Towards Immigration in Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (5): 1136–1161.

- Schmidt-Catran, Alexander W., and Christian S. Czymara. 2020. “‘Did You Read About Berlin?’ Terrorist Attacks, Online Media Reporting and Support for Refugees in Germany.” Soziale Welt 71 (2–3): 305–337.

- Schüller, Simone. 2016. “The Effects of 9/11 on Attitudes Toward Immigration and the Moderating Role of Education.” Kyklos 69 (4): 604–632.

- Schwemmer, Carsten. 2018. “Social Media Strategies of Right-Wing Movements-The Radicalization of Pegida.” SocArXiv.

- Sniderman, Paul M., Michael Bang Petersen, Rune Slothuus, Rune Stubager, and Philip Petrov. 2019. “Reactions to Terror Attacks: A Heuristic Model.” Political Psychology 40 (S1): 245–258.

- Sood, Gaurav. 2019. “Tuber: Access YouTube from R.” R package version 0.9.8.

- Spörlein, Christoph, and Elmar Schlueter. 2020. “Ethnic Insults in YouTube Comments: Social Contagion and Selection Effects During the German ‘Refugee Crisis.’” European Sociological Review 37 (3): 411–428.

- Vasilopoulos, Pavlos, George E. Marcus, and Martial Foucault. 2018. “Emotional Responses to the Charlie Hebdo Attacks: Addressing the Authoritarianism Puzzle.” Political Psychology 39 (3): 557–575.

- Votta, Fabio. 2020. “peRspective: Interface to the ‘Perspective’ API.” R package version 0.1.0.

- Waterfield, Bruno. 2015. “Greece’s Defence Minister Threatens to Send Migrants Including Jihadists to Western Europe”. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/islamic-state/11459675/Greeces-defence-minister-threatens-to-send-migrants-including-jihadists-to-Western-Europe.html