ABSTRACT

Swedes uphold progressive attitudes regarding family, sexuality, and gender norms. At the same time, Sweden has had generous immigration policies for decades. This leads to challenges for children of immigrants, who must navigate between expectations from their family and the surrounding society. Therefore, this study asks whether children of immigrants’ attitudes relating to family, sexuality and gender roles adapt and approach those of their Swedish-background peers, using the Swedish branch of the CILS4EU survey (n = 5434). We account for dynamics in three ways: We compare attitudes of first- and second-generation immigrants; compare attitudes of youth to those of their parents; and study change in youth’s attitudes over time. In favour of acculturation, we find that second-generation immigrants have more liberal attitudes than first-generation immigrants, that immigrant-background youth are closer to majority peers in attitudes than their parents are to majority parents, and that gender norms of immigrant-background youth move closer to those of Swedish-background youth over time. For attitudes relating to family and sexuality, however, we find a divergence in attitudes over time, but not because immigrant-background youth become less liberal: Their views do become more liberal, but majority youth see an even stronger change in the same direction.

Introduction

When it comes to attitudes, Sweden stands out. Compared to people in most other countries, Swedes more often reject tradition, religion and authority as moral guides, embrace gender equality, are positive to the right to divorce and abortion, and accepting of sexual minorities and new family forms (Inglehart and Welzel Citation2010; Inglehart Citation2018). Coupled with this overall progressiveness is a comparatively positive stance towards foreigners (van der Linden et al. Citation2017), which has allowed a high level of immigration for several decades. The latest decades have been dominated by refugee or humanitarian migration from Middle Eastern and African countries, where average attitudes differ strongly from the Swedish average on issues related to gender, family, and sexuality. Values in these migrants’ origin countries tend to be traditional, and tolerance for new family forms and sexual minorities is low. For example, the World Values Survey (Inglehart et al. Citation2014) documents that while only 8% of the Swedish population agree with the statement ‘Homosexuality is never justifiable’, corresponding numbers in Iraq and Turkey – two common origin countries among immigrants in Sweden – is 70% and 78%. And in Turkey and Iraq, 65% and 73% of the population do not want unmarried couples as neighbours – compared to 0% in Sweden. Differences like these are consistent across measures and studies, and generally dwarf within-country differences between, for example, men and women or educational groups (Inglehart and Welzel Citation2010).

While a strong inertia in attitudes to gender, family, and sexuality can be expected among those who immigrate as adults, it is much harder to predict the attitudes of the immigrants’ children, who often have spent most or all of their lives in Sweden. More than a quarter of minors in Sweden have two foreign-born parents (Statistics Sweden Citation2021), and these young people have been exposed to early socialisation within the family, but at the same time interact with Swedish peers and institutions from an early stage in their lives. Thus, we face a situation with a growing group of young people who are caught between normative systems that are often radically different.

In this paper, we ask whether immigrant-background youth in Sweden acculturate and get attitudes relating to family, sexuality, and gender equality that are similar to those of Swedish-background youth. Sweden is the ideal site to study acculturation dynamics, as it is extreme in terms of liberal attitudes and at the same time has a large and diverse immigrant population, enabling us to comprehensively account for heterogeneity in origins and to study attitude development for ‘most-different’ cases at the extreme opposites of the attitude spectrum. We use the perfectly suited Swedish branch of the longitudinal CILS4EU survey, and account for dynamics through three different approaches: We compare attitudes of youth who immigrated themselves with those of youth born in Sweden to two immigrant parents; we compare attitudes of youth to the attitudes of their parents; and we study the change in youth’s attitudes over time. These different approaches require different sets of assumptions in order to identify acculturation. As we apply these different approaches to the same sample of respondents, an important strength of this study is to show how differences in analytical strategies for assessing acculturation affect substantive conclusions.

Immigration to Sweden

Sweden’s history as an immigration country started with refugee migration during and after World War II, and from the 1940s onwards has received several waves of political refugees (see, e.g. Byström and Frohnert Citation2017). The 1960s and early 1970s also saw a large wave of labour immigration, primarily from Finland. From the 1980s onwards, both the nature and the volume of immigration changed, with large numbers of non-European refugee immigrants, mainly from the Middle East, and during the 1990s this was combined with immigration from the Balkans due to the civil war. The immigrant population in Sweden has increased from a few percent in the 1960s to 20% of the population in 2020 (Statistics Sweden Citation2021).

Sweden has had an exceptionally large non-European immigration in relation to population size (Eurostat Citation2020: Table 5). In the decade between 2009 and 2019, Sweden's population increased by almost one million, and 73% of this increase was due to net immigration (Statistics Sweden Citation2020). Immigration has also been diverse in terms of countries of origin, with the most common origin countries among the foreign-born being Syria (9.5% of all foreign-born), former Yugoslavia (9%), Iraq (7%), Finland (7%), Poland (5%), Iran (4%), Somalia (3.5%), Afghanistan (3%) and Turkey (2.5%) (Statistics Sweden Citation2021).

Native-immigrant differences in attitudes to sexuality, family, and gender

Internationally, the trend has been for societies to move from traditional and often religiously motivated attitudes towards more secular and liberal ones. Attitudes emphasising individual freedom, democracy, gender equality and tolerance of outgroups have become more prominent as societies have grown richer (Inglehart Citation2018; Roberts Citation2019). However, gaps across countries remain large, and according to Inglehart and Norris (Citation2003), the major cultural fault line (what they call the ‘true clash of civilizations’) concerns views on gender and sexuality. Although Inglehart and Norris emphasise the particularly large gap between Western and Islamic societies, their results show that there are in fact rather large differences between Western societies on the one hand, and most other world regions on the other, in attitudes to gender equality, homosexuality, abortion and divorce (Norris and Inglehart Citation2002: Table 3). In general, religiosity tends to go together with conservative attitudes, but eastern Europe is an exception as conservative attitudes there – at least in relation to homosexuality – appear to be a secular phenomenon (Doebler Citation2015).

Several studies have assessed attitudes among immigrants to Western countries. Unsurprisingly, they tend to find that immigrants from regions with more traditional value systems are less liberal than the majority population in their views on gender and sexuality. Many studies focus on Muslim-background immigrants, and they generally show stark differences between this group and the host population in attitudes concerning gender, sexuality, and outgroups (Bisin et al. Citation2008; Ipsos Mori Citation2018, 66; Lewis and Kashyap Citation2013; Koopmans Citation2015). Norris and Inglehart (Citation2012) find that Muslim immigrants in Western societies have attitudes that lie roughly in between their origins and destinations, interpreting this as a sign of cultural integration. This focus on Muslim/non-Muslim divides, however, has obscured the fact that differences between immigrants and the majority are not just a question of Muslims versus the rest. For example, Röder and Lubbers (Citation2015) find that Polish immigrants to the Netherlands, Germany, UK and Ireland are markedly less accepting of homosexuality than the destination country majority (but somewhat more accepting than the Polish average), and Friberg (Citation2016) finds that youth in families with Eastern European and Balkan background are less accepting of homosexuality than Norwegian-background youth (but more accepting than MENA-/African-background youth).

What can we expect for the Swedish children of immigrants?

Previous research tells us that immigrants differ in their average attitudes from the host population, and that the within-country differences between people with origins in different countries follow the same lines as cross-country differences. But what about children of immigrant parents? Some of them are immigrants themselves, having immigrated at young ages, while others are born in the destination country, but they share the experience of being exposed to two potentially different value systems.

Classical assimilation theory (e.g. Park Citation1950; Gordon Citation1964) would lead us to expect gradual acculturation as immigrants and their children are exposed to the host country culture and attitudes through, e.g. neighbours, institutions, peers, and the media. In particular, we would expect that those who are born and raised in the host country should be closer to the majority population’s attitudes than their parents are. The more general literature on cultural and attitudinal change suggests that attitudes crystallise in early adulthood and remain mostly stable thereafter, but that there is a period of ‘impressionable years’ in late adolescence and young adulthood when attitudes are more prone to change (Krosnick and Alwin Citation1989; Alwin and Krosnick Citation1991; Kiley and Vaisey Citation2020; Vaisey and Kiley Citation2021). Because immigrant-background youth experienced this period in Sweden, we would expect the Swedish context to make an imprint on their attitudes.

A similar prediction, but on other grounds, can be derived from Inglehart’s existential security thesis (Citation2018), according to which the societal level of security and prosperity affects motivations and thereby attitudes. According to this theory, a high level of existential security and a high standard of living make people less prone to turn to tradition and religion, and more likely to adopt liberal attitudes. Children of immigrants have generally experienced a higher standard of living and a higher degree of existential security for a larger part of their lives than their parents, and should therefore have a more liberal outlook.

Other theories, however, predict strong inertia and slow acculturation. Attitudes relating to sexuality and family issues are often transmitted through primary socialisation within the family, which is likely to make them more resistant to change than attitudes that are internalised during the later phases of life (Pettersson Citation2007). This theory is supported by Kretschmer’s (Citation2018) finding of a strong transmission of such attitudes from immigrant parents to their children, and also receives suggestive evidence from studies that find small or no differences in attitudes to gender and sexuality between those with immigrant parents who are born in the host country (the ‘second-generation’) and those who have immigrated themselves (the ‘first generation’) (Kalmijn and Kraaykamp Citation2018; Kogan Citation2018; Koopmans Citation2015).

Religion appears to be a major driver of the observed persistence in attitudes across generations. Immigrants, in particular those from Muslim-majority countries, are much more religious than the host country population, and religion is strongly transmitted within immigrant families. Islam has a particularly strong intergenerational persistence (Simsek et al. Citation2018; Jacob and Kalter Citation2013; Jacob Citation2020), and those who are more religious have more conservative attitudes (Kogan and Weißmann Citation2020; Röder and Lubbers Citation2015; Kogan Citation2018). Hence, religion and religiosity can potentially explain any lack of acculturation.

Something which has gained increasing interest lately (e.g. Ifop Citation2020) is the risk that a significant number of immigrant-background youth not only fail to acculturate to liberal attitudes, but rather become more conservative over time or generations. Ethnic or religious differences may become more entrenched, either due to a sense of threat, perceived ethnic conflict, or discrimination (so called ‘reactive ethnicity’ (Portes and Rumbaut Citation2001)), although recent studies question the empirical validity of this last mechanism (e.g. van Maaren and van de Rijt Citation2020). Moreover, ethnic differences in attitudes could become more pronounced due to an increased spread of ideas from conservative religious or ethnic organisations, or due to the contemporary emphasis on group identities as sources of both belonging and divisions. Thus, we will consider not only the possibility of stable or decreasing, but also of increasing gaps in attitudes over individual time and across generations.

The current study

We study cultural integration among immigrant-background youth (ages 14–19) from three different angles: First, we study whether youth born in Sweden with immigrant parents and youth who have immigrated themselves have different gaps in attitudes to youth from the majority population. Second, we compare youth’s attitudes with their parents’, and, third, we study how attitudes change over time for given individuals. We ask the following questions:

Do youth who are born in Sweden to immigrant parents (‘the second generation’) have attitudes that are more similar to Swedish-background youths’ attitudes than youth who have immigrated themselves (‘the first generation’)?

This is the most common way of addressing acculturation, with an intuitive logic: If attitudes change gradually with exposure to the new country (classical assimilation theory), or if attitudes become more liberal and progressive with increasing existential security, we would expect those born in the host country to have attitudes more similar to the majority population than those who immigrated themselves. Despite the popularity of this design, its results do not necessarily provide sharp evidence on acculturation. Different immigrant groups have come during different periods, so immigrant ‘generations’ often have very different composition in terms of origins: For example, if ‘first’ generation youth come predominantly from the Middle East, while many in the ‘second’ generation have parents born in the Nordic countries, a comparison will most likely show a difference in attitudes that can naively – but wrongly – be interpreted as acculturation. Our improvement in relation to much of the literature is that we can assess differences across generations within origin regions, and we also do this without limiting our analysis to only one specific region.

Convergence towards majority attitudes over generations tentatively supports classical assimilation theory as well as Inglehart’s existential security theory. The latter, however, would predict that this convergence is mediated by existential security, whereof socioeconomic conditions are a part. We therefore test to which extent the generational effect is mediated by family income, a post-migration characteristic. If such mediation is found, it is, however, still not conclusive evidence, as the estimated effect of income may be contaminated by confounders and reverse causality (those who are more culturally integrated may be more likely to get higher incomes). We also assess to which extent religiosity mediates the association, that is, whether any difference in attitudes across the synthetic generations go together with a similar difference in religiosity.

| (2) | Are children of immigrants more liberal in their family/sexuality- and gender role attitudes than their parents are, and if so, does this parent–child gap in attitudes differ from the one among Swedish-background youth? | ||||

This analysis moves from ‘synthetic generations’ to actual generations, comparing children’s attitudes to their parents’. The comparison is done within families, which eliminates any confounding caused by the differential composition of immigration cohorts. This design has been used in studies of attitudes among immigrants (Maliepaard and Alba Citation2016; Idema and Phalet Citation2007), but using samples without a non-immigrant comparison group. Because differences between children and their parents can be due to age effects, we extend this design by comparing the parent–children gap among immigrant-background youth to the parent–children gap among Swedish-background youth. Acculturation is thus operationalised as a difference-in-difference, i.e. the difference in the parent–child difference between majority- and immigrant-background youth. Classical assimilation theory and existential security theory would suggest the parent–child gap to be bigger among immigrant-background youth than among majority-background youth, and hence that the differences in attitudes are smaller in the child generation than in the parent generation.

| (3) | Do any gaps between Swedish-background youth and immigrant-background youth shrink over time, and does this acculturation differ across origin groups? | ||||

This analysis looks at changes in attitudes for given individuals over time, and as such is the cleanest design, giving clear evidence on the effect of time exposed to the Swedish setting on attitudes. Time being perfectly correlated with age makes it essential to control for general age effects by contrasting changes in attitudes among immigrant-background youth with changes over the same period among Swedish-background youth from the same birth cohort. The question is thus about changes in gaps, not changes in levels, and again we apply a difference-in-difference logic, where acculturation would be observable as a bigger change among immigrant-background youth than among majority-background youth – that is, a convergence in the groups’ attitudes over time.

Materials and methods

Data

We use panel data from the four waves of the Swedish branch of the Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Survey in Four European Countries (CILS4EU) (Kalter et al. Citation2013).Footnote1 The study sample is nationally representative for the age group (using weights). The respondents were sampled through a two-step cluster design where schools were drawn first, and then two classes in each school. All students in these classes were invited to participate in the survey. The sample was drawn from national school registers but because the focus of the survey is integration, schools with a high proportion of immigrants were oversampled to ensure enough power in analyses of different immigrant groups. Survey weights adjust for these different selection probabilities.

In the first wave, Statistics Sweden collected data from 14- to 15-year-old school children in late 2010 or early 2011 during school hours. Schools across Sweden were selected, and then two grade 8 classes within each school (and all pupils in them). The sample consists of 5834 students (school participation rate 92%; individual response rate 86%) leaving 5025 participating students from 251 school classes in 129 schools for analysis. Parents also filled out a questionnaire (response rate 59%), and additional parental information (e.g. income, education, year and country of immigration) was collected from registers of the total population.

The second wave, in 2012, also collected data in the school setting and the target sample was the same as for wave 1 (response rate 78%). The third wave was collected through a web survey in 2013 (age 16), and the fourth wave was finalised in 2016, at ages 19–20, using both web and postal surveys. W3 and w4 targeted all respondents in w1 and/or w2, and the response rates in w3 and w4 were 51 and 47%, respectively.

To prevent biased results due to selective attrition, missing values were filled using multiple imputations. Missing data, including missing parental data, were imputed for all 5448 respondents within the original sampling frame who participated at either wave 1 or wave 2. We used non-parametric imputation for mixed-type data that accounts for clustering, as described in Stekhoven and Bühlmann (Citation2012) and implemented in the R package missRanger. The imputation model used 1832 variables, and 50 MI datasets were generated. Deleting 14 respondents for whom migration status and region of origin could not be detected led to a final analytical sample of 5434 observations.

Variables

Family/sexuality-attitudes

This measure gives the mean response to statements asking respondents whether ‘Living together as a couple without being married’, ‘Homosexuality’, ‘Abortion’, and ‘Divorce’ is (1) always OK, (2) often OK, (3) sometimes OK, or (4) never OK. Answers are recoded such that higher values represented more liberal attitudes (1–4). Internal consistency (α) was .75.

Gender role attitudes

These are measured with the following question: ‘In a family, who should do the following?’, followed by four different tasks: taking care of children, cooking, cleaning, and earning money. For each task, respondents could indicate whether the task should be conducted by mostly the woman, mostly the man, or both about the same. Answers to the four items were dichotomised. For child care, cooking, and cleaning, gender role attitudes were classified as traditional (0) if the task was primarily allocated to the woman, and as modern otherwise (1). For paid work, the gender role was classified as traditional (0) if the task was primarily allocated to the man and as modern otherwise (1). The sum of modern responses comprised the final scale (0–4), with reliability α = .78.

Immigrant background

We distinguish first-generation youthFootnote2 (i.e. immigrant-background youth born outside Sweden), and second-generation youth (i.e. immigrant-background youth born in Sweden with two immigrant parents). These are compared to Swedish-background youth, defined as youth with at least one Swedish-born parent.

Region of origin

We distinguish Swedish-background youth (1) and first- or second-generation youth with origins in the following regions: (2) Other EU & Western; (3) Central/Eastern Europe and former USSR; (4) Balkans; (5) Middle East/North Africa; (6) Africa; (7) Asia; (8) Latin/South America. For details on how origin countries were categorised, see Table A1, Appendix A.

Gender

Respondents were coded as boy or girl.

Parental education

Custodial parents’ educational attainment, derived from population registers, is coded into 1 if any parent has a tertiary education, and 0 otherwise.

Household income

Household income is the total disposable household income (income from all sources net of taxes) of participants’ custodial parents. If guardians lived in different households, we take the average of their disposable household incomes. Information was collected from tax registers. A squared term accounts for non-linear effects.

Religious denomination

To answer the question ‘What is your religion?’, participants were provided with a list of options and a fill-in option. To prevent small cell sizes, responses are condensed to No religion, Christian, Muslim, and Other.

Religiosity

Respondents answered the question ‘How important is religion to you?’ with Not at all important, Not very important, Fairly important, or Very important.

Descriptive statistics are provided in Table A2, Appendix A.

Analysis

Analyses consisted of a series of OLS regressions contrasting average attitudes, or changes in attitudes, in different groups. In the text, we report tests of statistical significance for the highest-level contrast (e.g. between Swedish- and immigrant-background youth), while tables and figures contain more detailed comparisons and their confidence intervals. Throughout, we add controls in a stepwise manner. Previous research suggests that acculturation might be stronger for girls than boys (Idema and Phalet Citation2007). Therefore, we adjust for sex in order to prevent differential gender compositions of immigrant groups confounding estimates of acculturation. Furthermore, controls for parental education (for immigrant-background parents partly a pre-migration characteristic) account for lower levels of parental education in immigrant-background than Swedish-background groups. This is needed as children from lower educated parents may be socialised towards more conservative attitudes, given that lower-educated people on average uphold more conservative views than higher-educated people. In addition to adjusting for these potential confounders, controls for family income and religion/religiosity were added to explore two potential mediating mechanisms. We adjusted for family income (a post-migration characteristic) as a way to explore whether acculturation is mediated by existential security. Controls for religion and religiosity, lastly, were a way to explore whether higher levels of religiosity and different religious denominations in immigrant-background groups accounted for acculturation gaps.Footnote3

Addressing research question one, we first test whether attitudes differ between the first and the second generation among immigrant-background respondents, controlling for country of origin, such that we effectively compare first- and second-generation youth assuming that the composition of origins is the same in both generations. In the next step, we distinguish the first and the second generation within region of origin groups and contrast each of these origin/generation combinations with Swedish-background youth.

Research question two is addressed by regressing parent–child differences in attitudes on immigrant-background categories. Please note that in these models we did not only account for the sex of adolescents, but also the sex of the parent who filled in the questionnaire, and their interaction in order to fully account for differential compositions of the sex of adolescents, their parents, and the parent child dyad across immigrant groups.

To test research question three, we compare change in attitudes over age between Swedish- and immigrant-background youth, and between the more detailed origin groups. Note that follow-up data was not collected at the same point in time for our two dependent variables, meaning that comparisons of change between them must be interpreted with caution.

Results

Comparing synthetic generations

We start our analysis by studying whether children born in Sweden to immigrant parents (‘second generation’) have more liberal attitudes than youth who have immigrated themselves (‘first generation’). Compared to the second generation, the first generation is more conservative at age 14 in both family/sexuality-attitudes (b = −.18, 95% CI [−.30, −.07], p = 0.002) and gender role attitudes (b = −.29, 95% CI [−.49, −.10], p = 0.003), net of controls for origin country, sex and parental education.

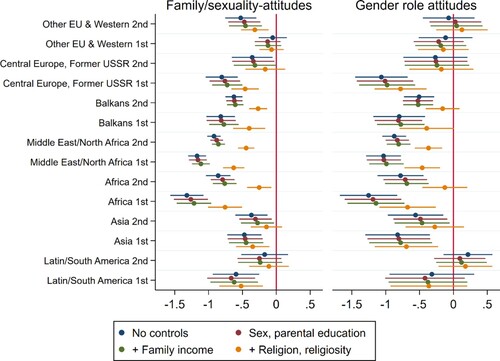

When comparing Swedish-background youth with first- and second-generation youth within each origin region (), the general picture is one of partial convergence: The second generation tends to have attitudes closer to the majority than the first generation.Footnote4 Substantial gaps in attitudes (0.5–0.8 points) do however remain in the second generation for African, MENA, and Balkan-background youth, suggesting that acculturation is not yet completed by the second generation. While the differences that we observe between generations is in line with (partial) acculturation, we cannot rule out the possibility that differences are due to some factor other than differential exposure to the Swedish context. Immigrant cohorts, even when they are from the same region, may differ on pre-migration characteristics related to attitudes. We can go some way in adjusting for differential composition by controlling for parental education, which is predominantly a pre-migration characteristic. In , we see that parental education accounts for a small part of the gaps to majority youth, but it has the same impact on the 1st as on the 2nd generation, so it cannot explain the difference between them.

Figure 1. Regression of attitudes on region of origin (ref. majority-background youth), immigrant generation and control variables.

Note: MI data, weighted. Points estimates (dots) and 95% CIs (lines) depicted. Negative coefficients = less liberal values than Swedish-background youth (reference category). Regression estimates underlying this Figure are presented in Tables A4 and A5 in Appendix A.

Differences in family income also do not account for the differences across generations, which suggests that a higher economic security is not the driver of the more liberal attitudes in the second generation. Furthermore, we see in that religion and religiosity is an important – but not the full – explanation for the attitude differences between immigrant- and Swedish-background youth. However, differences in attitudes between the first and second generation remain stable after controlling for religion and religiosity, so this difference is not mediated by a lower religiosity in the second generation.Footnote5

Comparing parents and children

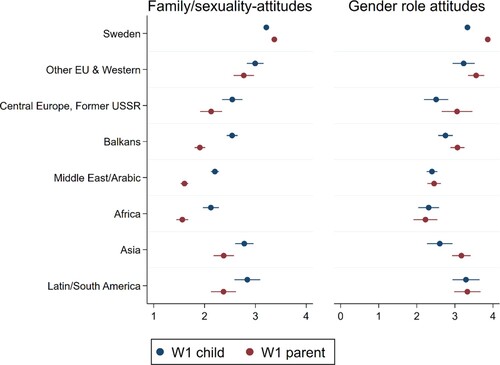

In the next step, we compare attitudes among youth to those of their parents. Univariate distributions of attitudes (Appendix A, Figures A5 to A10) show that cross-region differences are similar among parents as among children, but gender role attitudes, and in particular attitudes to homosexuality (Figure A10), are more polarised in the parental generation. Results for family/sexuality-attitudes, to the left in , show that at age 14, Swedish-background youth are slightly less liberal in their attitudes than their parents, but the opposite is true for immigrant-background youth, who have more liberal attitudes than their parents.Footnote6 For both these reasons, group differences are smaller in the child generation than in the parent generation. Moreover, parent–child difference tends to be larger in groups where parents have more conservative attitudes. The pattern among Swedish-background youth likely reflects an age effect in a population where the acceptance for abortion, divorce, cohabitation, and homosexuality has been high for a long time, while the pattern among immigrant-background youth is more likely a combination of a cohort effect (in many origin societies, older cohorts have less liberal views (Inglehart Citation2018)) and an acculturation effect (immigrant-background youth have been exposed to more liberal attitudes for a larger part of their lives than their parents).

Figure 2. Mean attitudes of respondents, and parents of respondents, in wave 1, by region of origin.

Note: MI data, weighted. Dots and lines represent point estimate and 95% CI of mean for each origin group. Higher values = more liberal attitudes.

Also for gender role attitudes (, right panel) Swedish-background youth have on average more conservative views than their parents, but in this case, this is true also for several immigrant-background categories. It is notable that this pattern tends to hold in groups where parents’ gender role attitudes are rather progressive, again suggesting an age effect, with youth being more conservative than adults in settings with more gender-equal norms. In MENA- and African-background groups, where parents’ gender attitudes are rather conservative, attitudes tend to be similar among parents and children. That is, youth do not acculturate to the more gender-progressive attitudes of their majority peers, but neither do they have more conservative views than their parents.

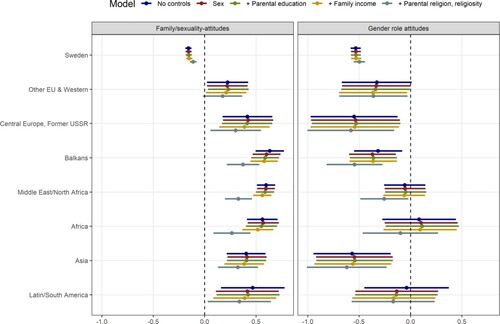

shows the average predicted parent–child gap by group, controlling for the gender of parents, children, and their interaction (model 1), parental education (model 2), family income (model 3), and parental religious denomination and religiosity (how important they find religion) (model 4). With regard to family/sexuality-attitudes, lower parental education and income and higher parental religiosity go together with more traditional attitudes among both parents and children, but more so among parents. Thus, parent–child differences in family/sexuality-attitudes are larger when parents have low SES or high religiosity, and the fact that these parental characteristics are overrepresented in some immigrant groups is one reason that parent–child gaps are larger in these groups. For gender role attitudes, the groups with the most conservative parents are the ones where youth deviate least from them. This is largely accounted for by religion and religiosity: Children tend to have more conservative gender role attitudes than their parents if parents have progressive attitudes but not if parents have conservative attitudes, and parental gender role attitudes depend strongly on religion and religiosity.

Figure 3. Average adjusted predictions of wave 1 child–parent differences in attitudes.

Note: MI data, weighted. Points estimates (dots) and 95% CIs (lines) depicted. Positive values mean that children have more liberal attitudes than their parents. Regression estimates underlying this Figure are presented in Tables A6 and A7 in Appendix A.

All in all, parent–child comparisons suggest partial acculturation: Children in immigrant families are closer to their majority peers in terms of attitudes than their (immigrant) parents are to Swedish parents. A plausible interpretation is that the experience of more liberal attitudes in the Swedish context pulls children in conservative families away from the attitudes of their parents, but this force is not strong enough to compensate for early socialisation, leading to remaining gaps in family/sexuality-attitudes between children of immigrants and their Swedish-background peers. For gender role attitudes, there is no liberalisation across generations, but in contrast to other youth, MENA- and African-background youth at least are not more conservative than their parents, meaning that the gap between them and their Swedish-background peers is smaller than the gap among the parents.

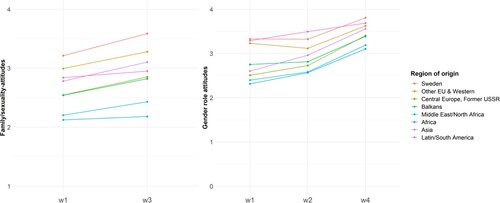

Change over individual time

A weakness of parent–child comparisons is that they may capture not only acculturation but also age and cohort effects, which – as we suggest above – may differ across origin groups. Our last test of acculturation avoids this by comparing attitudes over individual time, that is, changes in attitudes for given individuals upon changes in time exposed to the Swedish context. The left panel of shows changes in family/sexuality-attitudes between wave 1 (age 14) and wave 3 (age 16). Over this period, youth get increasingly liberal in all immigrant-background groups, even if the trend is rather weak in the African- and Latin American-background groups. Notably, youth of MENA-background see a clear liberalisation of attitudes.

Figure 4. Attitudes over waves by ethnic origin group.

Note: MI data, weighted. Dots represent point estimates of the mean per group and wave.

Importantly, however, also Swedish-background youth see a liberalisation that is parallel to, or steeper than, the one in the immigrant-background groups. Swedish-background youth have grown up with Swedish parents and hence the change in this group must be interpreted as an age effect on family/sexuality-attitudes. In the immigrant-background groups, a year of exposure is perfectly collinear with a year in age, so in order to purge the age effect from the exposure effect, acculturation must be assessed as the difference in the attitude change between immigrant-background and Swedish-background youth. The ‘fanning out’ of the lines in suggests increasing gaps between Swedish- and immigrant-background youth in family/sexuality-attitudes over age. That is, family/sexuality-attitudes become more progressive in all groups, but more so among Swedish-background youth.Footnote7 In line with , a test of differences in changes in family/sexuality-attitudes between Swedish- and all immigrant-background youth indicates a slightly slower change among immigrant-background youth (b = −.13, 95% CI [−.20, −.07], p < 0.001), net of controls for sex and parental education.

Gender role attitudes were measured at waves 1, 2, and 4 (ages 14, 15 and 19). Just as for family/sexuality-attitudes, the trend is towards less traditional norms (). At age 19, youth of all origin groups score between 3 and 4 on the 0–4-scale, so acceptance of progressive gender role attitudes is very strong overall.Footnote8 In contrast to the case for family/sexuality-attitudes, the convergence of the lines in the right panel of suggests a decrease of the gap between Swedish- and immigrant-background youth in gender role attitudes over time. A statistical test confirms this (b = .22, 95% CI [.10, .35], p < 0.001), net of controls for sex and parental education.

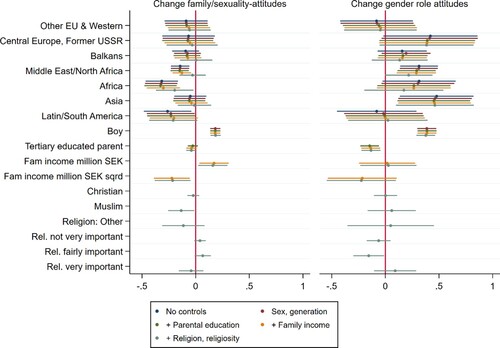

shows the difference between Swedish-background youth and different origin groups in the change in family/sexuality-attitudes and gender role attitudes. As could be derived from , all immigrant-background groups see a smaller change in family/sexuality-attitudes than Swedish-background youth, but the difference to the majority is only statistically significant on conventional levels for youth with background in MENA, African, and Latin/South America. The main effect of the control variables shows that boys see a stronger change, i.e. a ‘catch-up’ effect whereby they converge towards girls’ more liberal attitudes over age (note that this is a main effect of sex, averaged across both immigrant- and majority-background youth), and Muslim youth are slightly less prone to change. The higher representation of Muslims appears to be the driver behind the slower change among Balkan- and MENA-background youth, and partly explains the slower change for the African-background group.

Figure 5. Regression of change in attitudes on origin group (ref. Swedish-background) and control variables.

Note: MI data, weighted. Reference categories: Swedish background (vs. immigrant background); Girl (vs. boy); No tertiary-educated parent (vs. tertiary-educated parent); No religion (vs. Christian, Muslim, Other religion); Religion unimportant (vs. not very/ fairly/ very important). Negative coefficients = less liberal attitudes than the reference category. Regression estimates underlying this Figure are presented in Tables A8 and A9 in Appendix A.

The right panel of shows the convergence in gender role attitudes across groups over time, with most immigrant-background groups having a bigger change in gender role attitudes than Swedish-background youth. The difference in the size of the change is statistically significant for MENA- and Asian background youth, and borderline statistically significant for Central European, Balkan, and African-background youth. Also in this case, change in gender role attitudes is markedly stronger for boys, but there are no meaningful associations with religion, parental income or education, and the estimated differences between Swedish-background and immigrant youth are largely unperturbed by adding covariates.

Conclusions

Acceptance of homosexuality, cohabitation, divorce and abortion, and equal gender norms are issues that matter strongly to many people. They speak to core issues of human rights and female emancipation, and Sweden has prided itself with being highly liberal and progressive in these domains (Inglehart Citation2018). In the same liberal spirit, Sweden has had generous immigration policies for several decades, leading to interesting, and potentially challenging, meetings of cultures and attitude systems that sometimes clash in deeply held convictions. This clash will be particularly salient for children to immigrant parents, occurring in their daily lives and even within them when they simultaneously seek to navigate interactions with and expectations from the family of origin and the surrounding society. In this paper, we have focused on this group, asking whether their attitudes adapt to and approach those of their Swedish-background peers.

We find that youth who are born in Sweden to immigrant parents (‘second generation’) have more liberal family/sexuality-attitudes and gender role attitudes than same-aged youth who have immigrated themselves (‘first generation’). Moreover, children in immigrant families are closer to their majority peers in family/sexuality-attitudes and gender role attitudes than their (immigrant) parents are to majority parents. From these results, it seems that immigrant-background youth do acculturate to more liberal family/sexuality- and gender role attitudes. The stronger test, looking at change within individuals, also finds that gender role attitudes of immigrant-background youth move closer to those of Swedish-background youth over time. For attitudes relating to family/sexuality, however, we find a divergence rather than a convergence over individual time, but not because immigrant-background youth become less liberal. In fact, their attitudes do become more liberal over time, but Swedish youth see an even stronger change in the same direction, resulting in a net increase in the gap between immigrant- and majority-background youth.

The three designs have different strengths and weaknesses in detecting acculturation: The comparison of ‘synthetic’ generations (youth of 1st and 2nd generation) can be contaminated by differential composition of these generations on unobserved variables, although this concern is mitigated by the fact that we compare generations within origin regions/countries. The comparison of parents and children eliminates the risk of confounding from differential cohort composition, but runs the risk of picking up cohort and age effects if these differ across groups. And, finally, the comparison of changes over individual age between immigrant- and majority-background youth eliminates age and cohort effects, and is in principle the strongest analysis. However, it studies only a limited part of the life-span, meaning that if acculturation progresses in a non-linear manner over time, the changes at these ages may not be representative of within-individual acculturation at other ages. In this regard, a limitation of this study is that parental attitudes were only available at wave 1. Longitudinal information on parental attitudes would have allowed us to study if the acculturation patterns observed in youth also occurred amongst their parents, or whether differences in the parental generation were comparatively stable, which we are forced to assume now.

Our triangulation of designs shows that they cannot generally be seen as exchangeable, with the most important difference being that the indirect analyses of generational change suggest acculturation in both family/sexuality- and gender role attitudes, while the direct analysis of change over individual age shows convergence between Swedish- and immigrant-background youth only in gender role attitudes, and a divergence rather than a convergence in family/sexuality-attitudes. Thus, an important methodological conclusion is that results from studies based on different designs cannot be straightforwardly compared.

Most evidence supporting acculturation was provided by our indirect analyses (synthetic and real generations). Substantively, this could imply that acculturation is slow (i.e. not complete in the second generation) and mainly takes place in childhood and early adolescence, before our window of observation. The implication of early acculturation is also in line with the fact that more than half of the respondents in the group of first-generation immigrants immigrated before the age of ten (footnote 2): Our results returned meaningful difference between synthetic generations, even though the majority of first-generation immigrant-background youth spent roughly the second half of their life in Sweden. Moreover, a tentative conclusion of acculturation at early ages would also fit with previous cross-country findings showing that even though youth of Middle Eastern background have much more conservative attitudes than the Swedish majority, they are in fact much less conservative than the largely comparable origin groups in Germany and the Netherlands (Jonsson et al. Citation2012, using CILS4EU wave 1). So, although early socialisation likely predispositions immigrant-background youth to more conservative stances (Pettersson Citation2007) it seems to be tempered somewhat by a process of adaptation to host country average attitudes early in life.

This conclusion must however be reconciled with our finding that both Swedish- and immigrant-background youth tend to get more progressive attitudes over the teenage years. Attitudes are not fixed but subject to change during adolescence, but because trends among Swedish and immigrant-background youth are largely parallel, immigrant-/majority-background gaps remain largely unaffected. If attitudes are still malleable, why is there no change in the immigrant-/majority-background gaps across this period? It appears that adolescents, regardless of background, tend to move towards more progressive societal norms, but at the same time, a path dependence or stickiness in attitudes means that group differences hardly change.

These largely parallel trends are also interesting in light of segmented assimilation theory (Portes and Zhou Citation1993; Xie and Greenman Citation2011) and related recent perspectives (e.g. Ward and Geeraert Citation2016) stressing the importance of local contexts for variation in acculturation across different immigrant groups as well as individual immigrants. Do these parallel trends, for instance, signal that the social contexts for integration do not differ strongly across immigrant groups of different origins in Sweden? Or does it signal, perhaps, that the local social context is of most importance for acculturation only early in life (prior to our observation window), explaining the combination of substantial wave 1 differences across origin groups but fairly parallel trends? Such and related questions might pose interesting starting points for future research.

Our results on attitude change are relevant to the more general literature on age and attitude formation (e.g. Kiley and Vaisey Citation2020; Vaisey and Kiley Citation2021; Crocetti et al. Citation2021). A notable side result is that Swedish-background youth at age 14 are less progressive and liberal in their attitudes than their parents, but this gap is quickly eliminated as youth become more progressive/liberal during the teenage years. The marked liberalisation over age reported by both majority and immigrant-background groups in this study suggests that family/sexuality and gender role attitudes are still malleable during the teenage years, which suggests that the attitude formation process is different from attitudes towards ethnic outgroups, which have been reported to crystalise before the teenage years (Crocetti et al. Citation2021). Of course, there is a possibility that attitudes continue to become on average even more progressive/liberal in our studied cohorts, but this cannot yet be studied. That being said, rather than representing substantive change, there is the possibility that the observed association between age and attitudes in part represents a rise in social desirability bias, which is found to be higher in early adulthood than in adolescence (Vigil-Colet, Morales-Vives, and Lorenzo-Seva Citation2013; Davis, Thake, and Vilhena Citation2010). We therefore call upon future research that longitudinally assesses attitude change across adolescence to think of ways to adjust for social desirability bias.

In conclusion, acculturation seems to be happening, but its pace is slow and there is far from full convergence in the second generation. Large differences in the acceptance of homosexuality, cohabitation, divorce and abortion remain also among children of immigrants who have spent all or most of their lives in Sweden. In line with previous research, we find that youth with parents born in MENA and African countries have attitudes that are much more conservative than majority youth’s, but, interestingly, we find that youth with backgrounds in the Balkans and Central/Eastern Europe also have strongly conservative attitudes. This seems to call for a broader and more nuanced approach than the common focus on MENA in studies of cultural integration.

Geolocation information

Sweden

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (1.7 MB)Acknowledgements

For help with the imputation, we thank Georg Treuter, and for helpful comments, we thank Jan O. Jonsson, Simon Hjalmarsson, and participants at the 4th International CILS4EU conference and at the IntegrateYouth April 2021 seminar.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Survey data are available at www.gesis.org (ZA5353 data file).

2 Please note that the group of first-generation immigrant background youth includes participants who migrated to Sweden between the ages 6 and 10 (33%) or before age 6 (27%), which are sometimes labelled 1.5th and 1.75th generation immigrant background youth respectively (Parameshwaran Citation2013).

3 Please note that conditioning on religious denomination was not tautological from a statistical point of view as there is substantial variation in religious denomination by region of origin (see Table A3 in Appendix A for details).

4 Appendix A, Figures A1–A4 (rightmost panel) show separate regressions for family/sexuality scale items. The patterns across origins and generations are largely similar for the four items.

5 Overall, the immigrant generations differ somewhat in composition regarding religious denomination, the first generation consisting of comparatively more Muslim and less Christian youth than the second generation, whilst levels of religiosity differ very little across generations.

6 Appendix A, Figures A11–A12 show the distribution of child-parent differences in more detail.

7 In Appendix Figures A5–A10, change across waves is described in more detail, and Figure A13 shows the distribution of within-person change. Among other things, we can see that the change in the majority group primarily reflects more acceptance of divorce, abortion and homosexuality, as the acceptance of cohabitation is so high already at wave 1 that there is almost no space for further increases.

8 See also Appendix A, Figure A6.

References

- Alwin, D. F., and J. A. Krosnick. 1991. “Aging, Cohorts, and the Stability of Sociopolitical Orientations Over the Life Span.” American Journal of Sociology 97 (1): 169–195.

- Bisin, A., E. Patacchini, T. Verdier, and Y. Zenou. 2008. “Are Muslim Immigrants Different in Terms of Cultural Integration?” Journal of the European Economic Association 6 (2–3): 445–456.

- Byström, M., and P. Frohnert. 2017. “Invandringens Historia – Från “Folkhemmet” Till Dagens Sverige.” Delmi KunskapsövErsikt 2017 (5): 143.

- Crocetti, E., F. Albarello, F. Prati, and M. Rubini. 2021. “Development of Prejudice Against Immigrants and Ethnic Minorities in Adolescence: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies.” Developmental Review 60: 100959.

- Davis, C. G., J. Thake, and N. Vilhena. 2010. “Social Desirability Biases in Self-Reported Alcohol Consumption and Harms.” Addictive Behaviors 35 (4): 302–311.

- Doebler, S. 2015. “Relationships Between Religion and Two Forms of Homonegativity in Europe – A Multilevel Analysis of Effects of Believing, Belonging and Religious Practice.” PLoS ONE 10 (8): e0133538.

- Eurostat. 2020. Migration and Migrant Population Statistics. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Migration_and_migrant_population_statistics.

- Friberg, J. 2016. “Assimilering på Norsk. Sosial Mobilitet og Kulturell Tilpasning Blant Ungdom med Innvandrerbakgrunn.” Fafo Rapport 2016 (43): 93.

- Gordon, M. M. 1964. Assimilation in American Life: The Role of Race, Religion, and National Origins. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Idema, H., and K. Phalet. 2007. “Transmission of Gender-Role Values in Turkish-German Migrant Families: The Role of Gender, Intergenerational and Intercultural Relations.” Zeitschrift für Familienforschung 19 (1): 71–105.

- Ifop. 2020. Fractures Sociétales: Enquête Auprès Des 18-30 Ans. https://www.ifop.com/publication/fractures-societales-enquete-aupres-des-18-30-ans/.

- Inglehart, R. 2018. Cultural Evolution: People's Motivations are Changing, and Reshaping the World. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Inglehart, R., C. Haerpfer, A. Moreno, C. Welzel, K. Kizilova, J. Diez-Medrano, M. Lagos, P. Norris, E. Ponarin, and B. Puranen. 2014. World Values Survey: Round Six – Country-Pooled Datafile. Madrid: JD Systems Institute.

- Inglehart, R., and P. Norris. 2003. “The True Clash of Civilizations.” Foreign Policy 135: 63–70.

- Inglehart, R., and C. Welzel. 2010. “Changing Mass Priorities: The Link Between Modernization and Democracy.” Perspectives on Politics 8 (2): 551–567.

- Ipsos Mori. 2018. A Review of Survey Research on Muslims in Britain. https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/publication/documents/2018-03/a-review-of-survey-research-on-muslims-in-great-britain-ipsos-mori_0.pdf.

- Jacob, K. 2020. “Intergenerational Transmission in Religiosity in Immigrant and Native Families: The Role of Transmission Opportunities and Perceived Transmission Benefits.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (9): 1921–1940.

- Jacob, K., and F. Kalter. 2013. “Intergenerational Change in Religious Salience among Immigrant Families in Four European Countries.” International Migration 51 (3): 38–56.

- Jonsson, J. O., S. B. Låftman, F. Rudolphi, and P. Engzell Waldén. 2012. Integration, Etnisk Mångfald och Attityder Bland Högstadieelever. Appendix 6 of Statens Offentliga Utredningar 2012:74: Främlingsfienden Inom oss. Stockholm: Fritzes.

- Kalmijn, M., and G. Kraaykamp. 2018. “Determinants of Cultural Assimilation in the Second Generation. A Longitudinal Analysis of Values About Marriage and Sexuality among Moroccan and Turkish Migrants.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (5): 697–717.

- Kalter, F., A. F. Heath, M. Hewstone, J. O. Jonsson, M. Kalmijn, I. Kogan, and F. van Tubergen. 2013. The Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Survey in Four European Countries (CILS4EU): Motivation, Aims, and Design. Mannheim, GE: Mannheim University.

- Kiley, K., and S. Vaisey. 2020. “Measuring Stability and Change in Personal Culture Using Panel Data.” American Sociological Review 85 (3): 477–506.

- Kogan, I. 2018. “Ethnic Minority Youth at the Crossroads: Between Traditionalism and Liberal Value Orientations.” In Growing up in Diverse Societies, edited by F. Kalter, J. O. Jonsson, F. van Tubergen, and A. Heath, 303–332. Oxford: OUP.

- Kogan, I., and M. Weißmann. 2020. “Religion and Sexuality: Between-and Within-Individual Differences in Attitudes to pre-Marital Cohabitation among Adolescents in Four European Countries.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (17): 3630–3654.

- Koopmans, R. 2015. “Religious Fundamentalism and Hostility Against out-Groups: A Comparison of Muslims and Christians in Western Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (1): 33–57.

- Kretschmer, D. 2018. “Explaining Differences in Gender-Role Attitudes among Migrant and Native Adolescents in Germany: Intergenerational Transmission, Religiosity, and Integration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (13): 2197–2218.

- Krosnick, J. A., and D. F. Alwin. 1989. “Aging and Susceptibility to Attitude Change.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57 (3): 416–425.

- Lewis, Valerie A., and R. Kashyap. 2013. “Are Muslims a Distinctive Minority? An Empirical Analysis of Religiosity, Social Attitudes, and Islam.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52 (3): 617–626.

- Maliepaard, M., and R. Alba. 2016. “Cultural Integration in the Muslim Second Generation in the Netherlands: The Case of Gender Ideology.” International Migration Review 50 (1): 70–94.

- Norris, P., and R. Inglehart. 2002. “Islamic Culture and Democracy: Testing the ‘Clash of Civilizations’ Thesis.” Comparative Sociology 1 (3–4): 235–263.

- Norris, P., and R. F. Inglehart. 2012. “Muslim Integration Into Western Cultures: Between Origins and Destinations.” Political Studies 60 (2): 228–251.

- Parameshwaran, M. 2013. “Explaining Intergenerational Variations in English Language Acquisition and Ethnic Language Attrition.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37 (1): 27–45.

- Park, R. E. 1950. Race and Culture. New York: Free Press.

- Pettersson, T. 2007. “Muslim Immigrants in Western Europe: Persisting Value Differences or Value Adaptation?” In Values and Perceptions of the Islamic and Middle Eastern Publics, edited by M. Moaddel, 71–102. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Portes, A., and R. G. Rumbaut. 2001. Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Portes, A., and M. Zhou. 1993. “The new Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and its Variants.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 530 (1): 74–96.

- Roberts, L. L. 2019. “Changing Worldwide Attitudes Toward Homosexuality: The Influence of Global and Region-Specific Cultures, 1981–2012.” Social Science Research 80: 114–131.

- Röder, A., and M. Lubbers. 2015. “Attitudes Towards Homosexuality Amongst Recent Polish Migrants in Western Europe: Migrant Selectivity and Attitude Change.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (11): 1858–1884.

- Simsek, M., K. Jacob, F. Fleischmann, and F. Van Tubergen. 2018. “Keeping or Losing Faith? Comparing Religion Across Majority and Minority Youth in Europe.” In Growing up in Diverse Societies, edited by F. Kalter, J. O. Jonsson, F. van Tubergen, and A. Heath, 246–273. Oxford: OUP.

- Statistics Sweden. 2020. Folkmängd och befolkningsförändringar 2019. https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/statistik-efter-amne/befolkning/befolkningens-sammansattning/befolkningsstatistik/pong/statistiknyhet/folkmangd-och-befolkningsforandringar-2019/.

- Statistics Sweden. 2021. Population by Country of Birth, Age and Sex. Year 2000–2020. http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/en/ssd/START__BE__BE0101__BE0101E/FodelselandArK/.

- Stekhoven, D. J., and P. Bühlmann. 2012. “MissForest – non-Parametric Missing Value Imputation for Mixed-Type Data.” Bioinformatics (oxford, England) 28 (1): 112–118.

- Vaisey, S., and K. Kiley. 2021. “A Model-Based Method for Detecting Persistent Cultural Change Using Panel Data.” Sociological Science 8: 83–95.

- van der Linden, M., M. Hooghe, T. de Vroome, and C. Van Laar. 2017. “Extending Trust to Immigrants: Generalized Trust, Cross-Group Friendship and Anti-Immigrant Sentiments in 21 European Societies.” PLoS ONE 12 (5): e0177369.

- van Maaren, F. M., and A. van de Rijt. 2020. “No Integration Paradox among Adolescents.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (9): 1756–1772.

- Vigil-Colet, A., F. Morales-Vives, and U. Lorenzo-Seva. 2013. “How Social Desirability and Acquiescence Affect the age-Personality Relationship.” Psicothema 25 (3): 342–348.

- Ward, C., and N. Geeraert. 2016. “Advancing Acculturation Theory and Research: The Acculturation Process in its Ecological Context.” Current Opinion in Psychology 8: 98–104.

- Xie, Y., and E. Greenman. 2011. “The Social Context of Assimilation: Testing Implications of Segmented Assimilation Theory.” Social Science Research 40 (3): 965–984.