?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Although there has been increasing focus on the employment mobility associated with migration and return, a number of important research gaps can be identified. First, there has been greater focus on occupational mobility than on changes in economic activity, although it is their interaction which determines welfare outcomes. Moreover, most studies of economic activity have focused on either self-employment, or the simple dichotomy between being employed versus unemployed, neglecting the shifts between full-time, part-time, and casual employment. Secondly, research on the determinants of these different types of employment mobility has been relatively narrowly focused on individual economic factors. Most studies have been fragmented, especially lacking a comparative element. To address these gaps, descriptive statistics and Bayesian multilevel models are applied to a pan-European panel survey of 3851 young returned migrants. The findings disclose that positive shifts in employment mobility are more evident in economic activity than in occupations, and for those with a lower occupational status prior to migration. Although a range of significant determinants of employment mobility are identified, the findings also demonstrate that education is a major driver of occupational mobility, while marital and family status are important influences on economic activity shifts.

1. Introduction

There is a long-established interest in whether international migration and return can be a driver of employment change (King Citation1984) but returned migration has attracted increasing attention in context of the rapid growth of large-scale, often short- to medium-term and/or circular migration predominantly among young adults (King and Williams Citation2018). Evidence on whether migration and return leads to changes in employment among young adults – whether in occupational mobility or in economic activity levels – remains limited and fragmented (Barcevičius Citation2016; Tverdostup and Masso Citation2016). There has been little comparative international systematic analysis of the extent, and the determinants, of these complex individual changes in employment (Galgóczi, Leschke, and Watt Citation2012).

Most existing research has focused on skills and incomes, reflecting its roots in human capital theories (Sjaastad Citation1962). In terms of employment, the principal focus has been on occupational mobility, and on self-employment/entrepreneurship changes, especially between pre migration and migration (Straubhaar Citation2000). There is a growing body of research on the employment mobility of return migrants and although many papers analyse all age groups, in practice their samples tend to include a majority in the young adult category, defined here as 16-35, whether they rely on secondary sources (Masso et al. Citation2018) or primary survey data (Mytna Kureková and Žilinčíková Citation2020). However, a substantial gap remains in understanding of the overall employment mobility outcomes of migration and return: most research has analysed occupational mobility rather than economic activity shifts. Moreover, research on economic activity has mostly examined self-employment and the dichotomy between employment and unemployment, with little or no focus on the shifts between full-time, part-time and casual employment (see Masso et al. Citation2018; Martin and Radu Citation2012).

In response to these gaps, this paper has two main objectives: (1) to assess the extent of both occupational mobility and changes in economic activity, and (2) to analyse a broader range of the determinants of these changes than provided by the existing literature. A comparative perspective is also provided by analysing data for nine countries drawn from across Europe with contrasting migration and return trajectories, which contrasts with the strong focus on return migration to Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) in much of the extant literature. Europe provides a relevant case study because of the high levels of mobility and intended mobility amongst young adults (Williams et al. Citation2018).

2. Literature review

2.1. Migration, return and employment mobility

Contemporary European ‘return’ migration involves high numbers of skilled workers and students, whose movements are increasingly fluid (King and Christou Citation2011). Yet there are significant gaps in the emerging, but still fragmented, analyses of employment mobility between pre-migration and after return.

In terms of occupational mobility, positive outcomes may result because migrants have accumulated human capital, employers see migration as a signal of higher productivity, and migrants may be self-selecting (e.g. are more enterprising) (Williams and Baláž Citation2008). Migration can be a conduit for acquiring formal educational qualifications, which certificate the acquisition of skills and knowledge (King, Findlay, and Ahrens Citation2010), or for acquiring different types of knowledge or competences, particularly among young adults (Williams Citation2006; Palovic, Janta, and Williams Citation2021). These competences can be valorised after return thereby facilitating employment mobility whether amongst all age migrants (Carletto and Kilic Citation2011) or young adults (Williams and Baláž Citation2005).

However, it may be challenging to valorise skills in the form of occupational mobility after return (Tverdostup and Masso Citation2016), and the heterogeneity of migrant experiences highlights ‘imperfect human capital transferability’ (Basilio, Bauer, and Kramer Citation2017). Moreover, as Van-der-Heijden (Citation2002, 565) emphasises, knowledge only has value if it is recognised by others, including employers, and this may be a barrier to those young adults with foreign educational qualifications or work experience (Lulle and Buzinska Citation2017) or sometimes a facilitator (Palovic, Janta, and Williams Citation2021) of employment mobility for young adults in particular labour market contexts. The mixed positive versus negative findings in research on employment mobility post return are partly due to variable labour market opportunities in both countries of origin and destination, as well as differences in the composition of flows between these. This underlines the need for comparative studies.

Welfare outcomes depend not only on occupational mobility but also on changes in economic activity levels. The two components of employment change can move in the same direction (both positive or both negative) or in different directions (one positive, and one negative). Very few researchers have examined the combined changes in economic activity and occupational mobility (Martin and Radu Citation2012). This research gap has been compounded by the how economic activity has been operationalised, with most studies only examining being employed versus non employed rather than levels of economic activity, and sometimes self-employment, usually in studies of individual countries (Tverdostup and Masso Citation2016; Mytna Kureková and Žilinčíková Citation2020), or a pair of countries (Masso et al. Citation2018). Only Martin and Radu (Citation2012) provide a broader comparative analysis, but that is limited in only considering selected CEE countries rather than a broader European sample, only sampling returnees within the first year of return, and not differentiating casual from other employment forms. Therefore, a gap exists in analysing the combined effects of economic activity rates and occupational mobility in recent studies of European return migration.

2.2. Determinants of post-return labour market experiences

Human capital theories inspired much of the earlier theorising on employment mobility, with migration viewed as a cost–benefit transaction (Sjaastad Citation1962): the costs of migration are increasingly rebalanced over time as migrants acquire ‘national’ human capital that allows them to capitalise on their generic skills. This provides no incentive to return before retirement unless economic expectations are unrealised (Duleep Citation1994). The dilemma of how to explain return migration has subsequently been addressed in terms of relative prices between host and home country, consumption preferences, and the possibility of accumulating human capital abroad, which enhances earnings after return (Dustmann and Weiss Citation2007).

The dominant role of human capital theories has made socio-economic characteristics a major starting point of research. Education is found to be a good predictor of economic activity; better educated individuals are generally more likely to be employed after returning home (Dustmann and Kirchkamp Citation2002; Martin and Radu Citation2012; Coniglio and Brzozowski Citation2018). In many cases migration allows those with high levels of formal education to obtain more marketable further qualifications or skills (Grabowska and Jastrzebowska Citation2019). However, this is also linked to motivations, with noneconomic migrants generally being considered to be less positively selected with respect to human capital than economic migrants (Lundborg Citation2013; Zwysen Citation2019). There are examples of non-economic migration amongst intra-European migrants, notably Roma escaping discrimination in their home countries (Cook, Dwyer, and Waite Citation2011) but also those who are seeking to escape ‘social stagnation’ (Pratsinakis et al. Citation2020). However, most have economic or learning motivations, or these are blurred with a variety of non-economic motives (Williams Citation2006; Williams and Baláž Citation2005). The learning may be formal, as with students, workplace-based, or a more general acquisition of cultural and language knowledge beyond the workplace. All these experiences take place during youth-to-adult transitions in which young mobile Europeans engage in the process of ‘becoming’ (King Citation2018), and they are likely to influence their employment experience during migration and, ultimately, after return. Related to this are migration channels – tending to be more formal in the cases of students many of whom rely on Erasmus and other student mobility schemes (King, Findlay, and Ahrens Citation2010) – which shape the destination and return experience (Gill and Bialski Citation2011).

The link between motivation and employment outcomes after return can, however, be complex. There can be unexpected gains in terms of employment mobility, even for those whose primary migration goals had not been primarily economic (Grabowska and Jastrzebowska Citation2019). However, outcomes are contingent: in the context of Eastern European countries, employers were distrustful of skills and knowledge acquired during migration (Barcevičius Citation2016); similarly, the extent to which professional networks have been maintained can be important in the process of labour market reintegration (Barcevičius Citation2016). While human capital theories do provide insights into employment mobility, they can only explain part of the variability in employment mobility, especially changes in economic activity.

A second strand of research on determinants has focused on socio-demographic characteristics. The earlier findings suggested that older returnees were more likely to be non-employed, whether by choice or constraint (Dustmann and Kirchkamp Citation2002). However, more recent research – perhaps reflecting changes in the growth of shorter-term young adult migration and labour markets – indicates that older returnees are less likely to be unemployed and are more successful in the labour market, especially during the first year after arrival as Martin and Radu (Citation2012) found in their analysis of the first year after return. Turning to gender, Martin and Radu (Citation2012) found that women returnees are less likely to be unemployed in the first year after arrival, but women had lower overall economic activity rates than men. The latter aligns with the findings on return migration to Poland (Coniglio and Brzozowski Citation2018) but returned women migrants from Italy to Romania were often highly dependent on husbands or partners, especially if they returned to rural areas which mostly had weaker job opportunities (Vlase Citation2013).

Marital status and family composition (having or not having children) also influence changes in economic activity rates. A comparative study found that married women (of all ages) are less likely to be economically active than single migrants in the first year after return (Martin and Radu Citation2012), while individuals who had children are also more likely to be economically active (Coniglio and Brzozowski Citation2018). However, the literature is limited by its tendencies to explore the influence of age, gender, civil and family status from a simple dichotomy of employment versus unemployment/inactivity, rather than incremental changes in economic activity.

Third, Cassarino (Citation2004) emphasised that ‘the returnee's preparedness’ in terms of return willingness and readiness are important in shaping the employment outcomes of return. An empirical study of returnees of all ages to Slovakia by Mytna Kureková and Žilinčíková (Citation2020) found that the level of preparedness – the accomplishment of migration plans – was more important than other factors in this respect. In part this is related to the maintenance of social networks during stays abroad. A study of returnees to Hungary by Lados and Hegedűs (Citation2016) highlighted that because highly skilled returnees maintained ties with their former employers, this led to smoother reintegration to the Hungarian labour market compared with less skilled returnees. Lulle, Janta, and Emilsson (Citation2021) in their overview paper on European youth noted that the lack of social networks as well as lack of recognition of foreign qualifications pose obstacles to returnees’ labour marker reintegration.

Fourth, geography or territoriality – at the national or regional scale – also provides insights into employment mobility. In part, national differences reflect variation in the degree and nature of the selectivity of return to different countries (Anacka and Fihel Citation2012). However, the key factor is the dynamism and openness of labour markets, and the structure of employment opportunities (Tverdostup and Masso Citation2016) in different countries and regions of origin and return (see also Hagan and Wassink’s Citation2020 overview). Smoliner, Forschner and Nova (Citation2012) report national differences in the outcomes of return of migrants of all ages to Central and Eastern Europe between 2005 and 2008 – returnees to countries other than Hungary tended to be unemployed, and only Polish returnees experienced higher levels of economic activity compared to pre migration. If the labour market lacks dynamism, or employers do not recognise the value of skills acquired abroad, not only is upward occupational mobility constrained, but migrants may even experience downwards mobility. This was the case amongst returned migrants to Estonia and Slovakia, who both faced short-term unemployment after return (Masso et al. Citation2018). Staniscia et al. (Citation2021) also reported differences amongst the experiences of returnees to Southern Europe: young Spanish returned migrants experienced more challenges than young Italian returnees, possibly associated with national differences in youth unemployment rates.

A major question is whether migrants return to their region of origin, or to a different region, and the relative economic dynamism of these. In Europe, rural-urban drift was characteristic of the return of relatively unskilled (and relatively older) migrants to southern Europe in the 1980s (King Citation1984), with those returning to urban areas demonstrating greater employment mobility in terms of occupations and economic activity. This is similarly evident in more recent studies of return migration to Poland (Grabowska-Lusińska and Okólski Citation2009). However, more recent migrants from non-metropolitan areas tend to return to their hometown or village, rather than to more dynamic regions, in Europe (White Citation2014) because of the availability of support networks (Galgóczi, Leschke, and Watt Citation2012).

Fifth, the temporality of the migration process matters. The duration of migration – both the length of time abroad and the number of trips abroad – does have a positive impact on the acquisition of skills of competences, but these are mostly informal competences rather than formal qualifications (Janta et al. Citation2021). The evidence on how this impacts on employment is contradictory. On the one hand, Dustmann and Kirchkamp (Citation2002) argue that those with higher wage opportunities abroad tend to have shorter migrations because they can fulfil their goals more quickly. In contrast, Saarela and Rooth (Citation2012) in their study of migrants of all ages from Finland to Sweden note that those who performed worse than expected in the host country became returnees relatively quickly. However, there is a notable lack of systematic research on how the temporal characteristics of migration shape employment mobility amongst young adults in Europe.

More recently, the importance of socio-psychological characteristics has also been recognised, but little researched to date other than in relation to human capabilities such as resilience and independent decision making (Grabowska and Jastrzebowska Citation2019). Risk aversion has also not been previously considered, even though it is known to be a significant determinant of migration (Williams et al. Citation2018).

Responding to the research gaps identified above, this research focusses on both types of employment mobility (economic activity and occupational activity), and the relationships between these, while also analysing a broader range of macro and micro determinants of employment mobility than previous studies. We focus on young European returned migrants, a group with high rates of migration intentions (Williams et al. Citation2018), and high rates of return and circular migration (King and Williams Citation2018).

3. Data and methods

3.1. Data collection and processing

Independent (X) variables were collected from primary (survey) and secondary (census) data sources. The data on individuals were drawn from an online-panel survey of young adults (aged 16-35) conducted by one of the largest market research organisations in the world – GfK (Belgium) and commissioned by the European H2020 YMOBILITY project. A single international agency was used to maximise comparability and quality control. Offline engagement techniques (mail and telephone) were used by GfK to sample a wide cross-section of society – this approach exceeds the reach of social media surveys, which oversample the views of the privileged (Hargittai Citation2020). Pilot testing in all required languages was conducted to ensure the language use accuracy and precision of the questions. Data collection lasted about three months from November 2015 to January 2016, in Germany, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Romania, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden and UK. These nine European countries represent a broad range of migration and socio-economic conditions, and histories of EU membership.

The YMOBILITY online-panel survey recorded 29,679 responses from 24,146 young adults that have never emigrated from their home country (81.3%), 1682 young adults currently living outside of their home country (5.7%), and 3851 young adults with 6-months or more international migration experience that are currently living in their country of birth (13.0%). Each of the national samples met the survey target of 200 respondents with migratory experiences (see Appendix A). Overall, the samples matched national statistics reasonably well with respect to age and gender distributions, although education attainment levels are typically above the national standards (see Appendix B). This is to be expected as young Europeans migrants (and those considering) tend to be highly educated. The present study focuses on the returned-migrant sub-samples of this large survey. It is important to note that national statistics describing the composition of internal and external migrants are currently either unreported or not collected by countries within Europe – this makes it impossible to construct meaningful survey weights to control for under sampling within the return migrant sub-population. Besides, any potential reduction in bias from the use of weighted estimates must be balanced against increases in variance (i.e. the trade-off between model explanation and prediction uncertainty). Gelman (Citation2007) demonstrates that survey weights are redundant in regression models with hierarchical structures that separate the influence of sub-populations from an overall response model. We ‘condition’ the outcomes through the inclusion of age, education, and geographic structures – The results find these to be of minimal influence, indicating that a representative sample has been obtained (see and ).

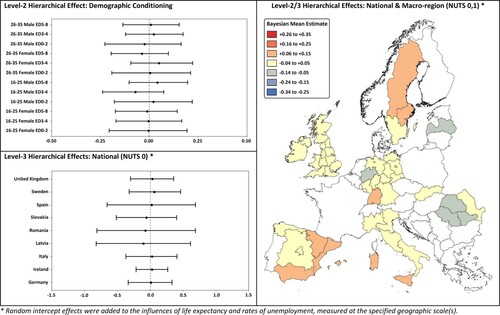

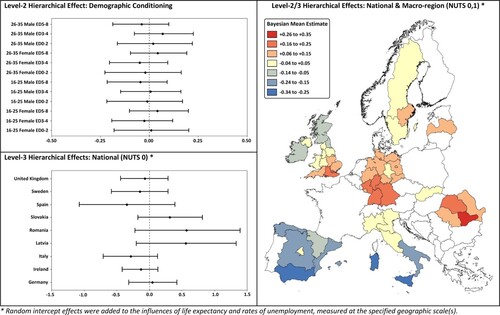

Figure 1. Pan-European multilevel model structures of occupational developments amongst returned migrants (random effects).

Figure 2. Pan-European multilevel model structures of economic activity change amongst returned migrants (random effects).

The YMOBILITY survey contains responses for binary outcomes (i.e. male or female), categorical groups (i.e. education levels), continuous measures (i.e. years of age), and a collection of 5-point Likert scale questions inviting respondents to individually self-assess influences on their migration decision or a specific socio-psychological response (where 1 = very low and 5 = very high). The number of periods spent outside of the home country for six or more months was recorded on a 3-point Likert scale: once, twice, three or more times.

Secondary data on life expectancy, unemployment, and GDP per capita in purchasing-power-standards were obtained by national (NUTS0) and macro-region (NUTS1) population-group structures from Eurostat (http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database). Eurostat is the statistical office of the European Union, responsible for the harmonisation of official records collected by member states to ensure that comparisons can be made at national and regional scales of governance.

There are seven main groups of individual variables aligned with the discussion of determinants in the literature review. These measurements represent either the pre-migration (Stage 1) or return migration (Stage 3) circumstances of each person:

Socio-demographic characteristics: Current age and gender (Stage 3). pre-migration marital and child status (Stage 1).

Socio-economic characteristics: Current education attainment level (Stage 3) and the pre-migration occupation status (Stage 1).

Socio-psychological characteristics of migration: Willingness to take risk (Stages 1–3).

Motivations behind the initial decision to migration (Stage 1): Career development, skill acquisition, and lifestyle experiences.

Migration channels and the influence of established networks in the destination country (Stage 1).

Temporal characteristics of migration: number of years and periods spent abroad (Stage 3).

Geographical characteristics of migration: Current national and regional measures of socio-economic standards for the location that migrants have returned to in their home country (Stage 3). The place of residence before relocating to another European country (Stage 1) is described by a self-reported rural-urban classification (city versus town versus rural), and the European Union accession phase of the home country (EU12, EU13-15, EU16-25, EU26-28, or settled status).

Table 1. Descriptive overview of the occupation and economic activity ranking systems.

Pre- and post-migration levels of occupational mobility were logically ranked for 1275 out of the 3851 survey respondents: 1011 persons that moved between unranked occupations (i.e. homemaker, job seeker, student, and other occupations), 1015 persons with unranked occupations before migrating, 241 persons that returned to an unranked occupation, and 309 persons that did not record a pre-migration occupation were omitted. Pre- and post-migration levels of economic activity were logically ranked for 2666 out of the 3851 survey respondents: 581 current students, 307 persons classified as self-employed, and 297 persons that did not record a pre-migration economic activity were omitted.

A regression analysis will only model participants that have a complete set of variables. Gelman and Hill (Citation2006, 531) note that the removal of incomplete records may cause biases because of potential differences between the units with missing values and the completely observed cases. In this study, core survey questions were answered in full. Response rates for the 17 Likert questions on migration reasons ranged from 67% (company transfer) to 91% (language skills). To avoid the removal of records a missing-data imputation approach known as iterative regression imputation was conducted on the migration reason responses, until approximate convergence of the data was achieved (r-squared > 0.5) (Gelman and Hill Citation2006, 539). This process produces informed responses and in a worst-case scenario generates random noise to prevent the removal of other important parameter responses from a complete-case analysis.

The necessary data processing steps were then performed:

Interpretation: Grand Mean Centring of the numeric x-variables to maintain the predictor-response relationships and ensure that Likert scales have a meaningful zero value.

Scaling: The centred predictors were divided by 2 standard deviations so that all coefficients could be interpreted roughly on a common scale. The only exception is the intercept, which now corresponds to the average predicted outcome when all inputs are at their mean values (Gelman and Hill Citation2006).

Multicollinearity: Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) diagnostics were conducted to select appropriate candidate explanatory variables for inclusion at each level of the regression model (see Appendix C). This followed an iterative process, involving: (i) the removal of the largest VIF scoring variable in a pairwise linear correlation >0.5, and (ii) the exclusion of variables with multicollinearity issues as indicated by VIF scores >5. This avoids instability in regression parameter estimates associated with collinearity.

3.2. Bayesian multilevel modelling

Multilevel regression models are suitable for the analysis of data with hierarchical structures (or nested sources) of variability, which arise in datasets exploring different demographic and geographic sub-populations (Gelman and Hill Citation2006). Applying standard statistical techniques to multilevel data violates the assumption of independent errors. Multilevel models can account for both individual and group-level (including territorial) influences simultaneously. The following models use survey data collected from individuals and secondary data of socioeconomic indicators collected at national and regional levels.

A Bayesian multilevel framework was adopted following recent criticisms of significance testing against arbitrary thresholds (Wasserstein and Lazar Citation2016). Bayesian approaches construct likelihood functions on the data and can therefore assign probability to the occurrence of any event with robust estimates of uncertainty. This approach is used to evaluate the range of influence that each determinant has on the outcome (in terms of magnitude and direction).

Bayesian multilevel models based on Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulation were conducted in R-programming through the runjags 2.0.4-2 package, interfacing to JAGS version 4.2.0 (Denwood Citation2016). A 4-chain simulation procedure was implemented for all models; the initial 10,000 simulations were omitted as part of the model burn-in procedure, and the next 10,000 sampled simulations were maintained for model interpretation. Limited guidance was found in the existing literature, therefore the models used minimally informed priors to create a posterior distribution.

The pan-European multilevel models follow a three-level hierarchical nesting structure, with many survey responses (Level-1) spatially nesting into NUTS-1 macro-regions (Level-2) and NUTS-0 countries (Level-3). Level-2 spatial structures were set up to comply with Hox’s (Citation1998) 50/20 rule for multi-level modelling with a cross-level interaction design, that is, 50 hierarchical groups, each containing 20 or more observations. A 36-group non-spatial demographic structure based on age (16–25 or 26–35 years), gender (male or female), and education (primary, secondary, or higher) was included at level-2 to condition the data (i.e. correcting for over or under sampling of certain population groups). The use of survey weights was not possible because detailed records of returned migrants were non-existent on a pan-European scale. The resulting pan-European models were fitted in the following form:

where is the measured occupational or employment status change for person i, with cross-level membership of demographic j and region k subpopulations (level-2), inside of country l (level-3).

As with linear regression, the intercept (response baseline) is , with the contribution of any other variables captured by fixed effect estimates

.

The contribution of the three hierarchical nesting structure intercepts (,

and

) is unique to each

combination, and the influence of group level predictors from secondary data sources are explained by

(level-2) and

(level-3).

The errors with variance represent the natural ‘within-cluster variation’ of survey respondents, with errors

and

respectively representing unexplained variation between the level-2 and level-3 multilevel structures.

4. Findings

4.1. Pan-European survey response

and summarise transitions in the ‘pre’ and ‘post’ migration occupations and economic activity of the pan-European survey panel for nine EU member states.

Table 2. Changes in occupational mobility for ‘Pan-European Returned Migrants’

Table 3. Changes in economic activity for ‘Pan-European Returned Migrants’

The first finding is that most respondents had not realised occupational mobility. Some two thirds returned to approximately the same broad type of occupational status as they had prior to migration. However, a substantial minority experienced occupational mobility, mostly upward mobility: 27.0% of migrants returning to a higher ranked occupation and only 6.8% returning to a lower ranked occupation. Occupational mobility, however, varied across occupational groups, and given the generally upward direction of mobility, unsurprisingly this was least for the highest ranked group who by definition could not record upward occupational improvements at this level of occupational categorisation (see ). There were broadly similar patterns of mobility for the clerical & administrative, and the skilled manual groups but approximately twice as great a level of upward mobility amongst those in the lowest ranked occupational group.

Although there is evidence of considerable occupational mobility, there are even more substantial changes in economic activity, with just under a half returning to the same type of economic activity status. This underlines the importance of looking at both occupational and activity-level changes. Overall, 49.3% of migrants returned to a higher ranked category, and only 8.6% returned to lower activity. The individual transitions again varied in relation to their pre-migration status (see ). The direction of change is clear, with increased levels of activity being recorded in every single group, except for those previously in full-time jobs who, by definition could not move upwards to a higher level of activity.

presents a crosstabulation analysis of the occupational mobility and change in economic activity experienced by returned migrants. 42.0% of the returned migrants considered in this analysis provided valid responses for both items (n = 1166). Nearly half of the respondents reported ‘no change’ in occupation and ‘no change’ to their economic activity, following a period of living abroad: this confirms the strong element of stasis, at least at this scale of analysis of employment mobility. 13.0% reported a double positive movement, that is both economic activity and occupational gains upon their return. In contrast, very few – only 1.1% of those surveyed – experienced a double decline in both their economic and occupational status. A further 28.7% experienced gains in one outcome, when either their economic or occupational status remained the same. Meanwhile, 6.6% experienced a decline in one outcome, when either their economic or occupational status remained the same. Only 2.8% of the respondents experienced a pair of inverse related shifts, that is decline in one outcome, when either their economic or occupational status increased.

Table 4. Crosstabulation analysis of the occupational mobility and change in economic activity of ‘Pan-European Returned Migrants’Table Footnotea,Table Footnoteb.

We may conclude that the risk of decline in individual measures of employment mobility are low following a period of living abroad, with only 10.5% of those sampled reporting an adverse outcome. In contrast, 41.7% of respondents reported either double or singular gains on the two axes of employment mobility following a period of living abroad. Significant and positive associations between the ranks of occupational mobility and economic activity were reported by the Pearson's Chi-squared test (P < 0.01), and Spearman's pairwise rank correlation coefficient (Rho = 0.42, P < 0.01).

4.2. Regression analysis

A regression analysis was conducted to better quantify these incremental shifts in economic and occupational ranks brought about by migration experiences, after controlling for demographic, economic, psychological, social, and spatiotemporal differences in the surveyed population. The developed models also quantify the influence of each of these controlling variables, which may then be used to describe the human capital losses or gains experienced by a return migrant with a specific profile. The models only include variables that could be collected before a migration decision was made. These models may (1) guide the decision-making process of individuals, and (2) act as a tool for policy makers to forecast human capital changes in young adults.

Please note that the coefficients were created using transformed data and their size reflects the importance of each parameter. Coefficients (β) for continuous and interval variables can be interpreted in terms of an x-unit increase on their original scale by referring to the standard deviation (σ) of the untransformed variable (see Appendix C) where y = β * (x/2σ).

4.2.1. The determinants of occupational mobility

The pan-European model of the determinants of occupational mobility, displays a moderate goodness-of-fit to the dataset of 1275 applicable survey participants, as demonstrated by adjusted loglikelihood (Nagelkerke-R2 = 0.38) and variance derived (Xu-Ω = 0.31) pseudo r-square measures (see Appendix D). The overall statistical validity of the model is confirmed by two Chi-Square Likelihood Ratio tests, where P < 0.01 (Appendix D): The first test ensures that any gains in predictive power (from the included set of parameters) sufficiently compensate the added level of model complexity, with the second test validating the inclusion of hierarchical effects (Galwey Citation2007, 213). contains the complete list of initially considered variables – those with blank cells are candidate variables omitted due to multicollinearity. Under the Bayesian framework, the performance of each parameter was then assessed by (1) Gelman-Rubin potential scale reduction factors (PSRF) and (2) serial autocorrelation in the parameter simulation samples: PSRF values <1.05 (Gelman and Rubin Citation1992) and minimal 10-lag interval autocorrelations (−0.01–0.02) indicate adequate parameter convergences.

Table 5. Multilevel model outputs for occupational mobility and economic activity changes amongst returned migrants (fixed effects).

presents the pan-European modelled determinants of occupational shifts between pre- and post-migration (Model 1). P-values were calculated for each parameter from the mean coefficient value and standard error, to allow for a traditional identification of key model parameters. For presentational purposes, the significant variables (P ≤ 0.05) were then ranked by their magnitude of influence on occupational shifts. The use of 95% highest density intervals is considered more informative for further interpretation of the data.

The 10 most important influences on the occupational mobility of return migrants across Europe are as follows (listed in descending order where P ≤ 0.05):

Socio-economic: Unskilled manual occupations prior to migration (+)

Socio-economic: Skilled manual occupations prior to migration (+)

Socio-economic: Reached a primary education level (−)

Socio-economic: Reached a secondary education level (−)

Socio-economic: Clerical and administrative occupations prior to migration (+)

Socio-economic: Reached a post-secondary education level (-)

Networks: Relocated through company policy (+)

Socio-psychological: A willingness-to-take-risk (+)

Motivations: To obtain a tertiary level of education (+)

Motivations: To join family or a partner (−)

An upward shift in occupational mobility may also be influenced by personality traits and migration channels. Individuals that were highly willing to take risks (Likert scale = 5) tended to gain additional 0.29 occupation ranks on their return, compared to those less willing to take risks (Likert scale = 1). Individuals with a strong desire to join family or a partner abroad (Likert scale = 5) typically returned to an occupation 0.14 ranks lower than those that migrated for their own reasons (Likert scale = 1). Individuals that migrated because of company policy tended to return to a higher occupational position, that those that migrated with no concrete plans (+0.22 rank difference). It is unclear, whether most of these gains were achieved from returning to a position within or outside of the company that organised the initial relocation. Small upward shifts in occupational mobility were also influenced by the increased age of a returned migrant (+0.12 ranks per 10-year increase) and for individuals that in part decided to migrate for lifestyle or cultural reasons (+0.15 rank difference). No significant differences in the occupational mobility of return migrants were found due to the broader array of socio-demographic characteristics (i.e. gender, marital or family status), or from regional and national variations in living standards at the point of return.

The outcome of migration is a complex trade-off between risks and rewards in terms of occupational mobility – most returnees experience a positive or no occupational shift, but there is also a risk of downward shift. Individual experiences are mediated by a range of characteristics, with many elements being shown to offset significantly the overall increase or decline in occupational skill development ().

Hierarchical structures within the multilevel model were used to further control for occupational changes experienced by different sub-population groups and in each territory (). The survey contains a representative sample of returned migrants with minimal conditioning of the population sub-groups required. In terms of geographical differences, minor variations in occupational change (−0.10 to + 0.10 ranks) were observed across the NUTS1 macro-regions that migrants returned to. Overall, and somewhat surprisingly, hierarchical structures are only weakly associated with occupational change.

4.2.2. The determinants of changes in economic activity

Economic activity is ranked in terms of the ‘intensity’ of employment (full-time > part-time > casual > unemployed). The multilevel model has a high goodness-of-fit to the dataset of 2666 applicable survey participants (Nagelkerke-R2 = 0.86) and it meets the aforementioned statistical thresholds (see Appendix D).

presents the pan-European multilevel model results for the determinants of change in economic activity (Model 2). The 10 most important influences in descending order are as follows (where P ≤ 0.05):

Socio-economic: Unemployed prior to migration (+)

Socio-economic: Casual or seasonal employment prior to migration (+)

Socio-economic: Reached a primary education level (−)

Socio-economic: Part-time employment prior to migration (+)

Socio-demographic: Persons that have children and are separated from their partner prior to migration (−)

Socio-economic: Reached a secondary education level (−)

Geographic: Higher national levels of life expectancy (−)

Socio-demographic: Persons without children and are separated from their partner prior to migration (−)

Socio-demographic: Male gender (+)

Socio-economic: Reached a post-secondary education level (−)

There is a strong likelihood that individuals leaving casual, seasonal or no form of economic activity tended to return to full-time employment. However, these reported gains may be offset by pre-migration civil status and the education level of returned migrants. Persons that had been separated from their partner (divorced or widowed) prior to migration tended to lose half an economic activity rank on their return – the model indicates that an entire rank is nearly lost by individuals with children that were separated from their partner prior to migration. It is difficult to comment on individual circumstances but the event of losing a partner is a major challenge, and a shock to be overcome. Further research is required to investigate whether, therefore, positive employment outcomes were not guaranteed if migration was primarily used as an escape mechanism. Levels of economic activity are shown to decline incrementally in relation to reduced levels of schooling – someone with a primary education was expected to return to an economic activity that was one rank below their university-educated counterpart.

Several geographical characteristics have moderate influences on economic activity. Migrants returning to countries with higher levels of life expectancy tended to re-join at a lower level of economic activity (i.e. −0.47 ranks per 5-year increase in life), perhaps as a result of increased competition from an older workforce. The type of area a person lived in before they first moved abroad was also seen to have a small but lasting effect, with persons growing up in urban areas maintaining a higher level of economic activity than their rural counterparts (+0.18 rank difference). A gap in economic activity also appears to persist between those born in EU and Non-EU countries: Returned migrants from EU12 countries typically occupied economic activity 0.33 ranks above those that returned to a European country where they had previously been granted settled status.

A small but noticeable difference by gender is observed, with males typically returning to an economic activity 0.38 ranks above their female counterparts. An upward shift in economic activity may also be influenced to some extent by the age of a returned migrant, previous levels of job security and migration networks. A 10-year increase in the age of a returned migrant was associated with a 0.21 rank increase in economic activity (i.e. the difference in economic activity gains, when comparing a 35 to a 25-year-old returned migrant). Migration channels are of moderate to low importance. Individuals whose migration plans were in part organised by their employers working abroad scheme, student programmes, or through a recruitment agency in the destination country returned to economic activity with 0.14-0.36 ranks above those that went opportunity seeking. Individual motivations for migrating such as changes to lifestyle, culture, career advancement and to re-establish family or social networks did not significantly influence any change in economic activity.

presents the hierarchal structures of the multilevel model, which describes changes in economic activity. As before, the survey contains a representative sample of returned migrants with minimal conditioning of the population sub-groups required. Hierarchical effects at a national level reveal that returned migrants to Romania and Latvia tended to move up 0.5 occupational ranks (95% CI = −0.22 to 1.39), but these may in part be offset depending on the macro-region they returned to. Significant yet relatively small variations are observed in the combination of national (NUTS 0) and macro-regional (NUTS1) effects, with individuals returning to capital cities and their hinterlands typically tending to experience increased levels of economic activity: Bucharest (RO), London (UK), Madrid (ES), and Stockholm (SE) are prominent in this respect. Clear north–south divides are also observed in the UK and Italy.

5. Discussion

Migration can provide opportunities to acquire knowledge, competences, or skills (Williams and Baláž Citation2008), however, the link between these acquisitions and the employment outcomes of returned migrants is poorly understood. The paper brings a pan-European perspective on young adult return migration to the hitherto largely fragmented evidence in this field.

5.1. Employment mobility: stasis and change

The findings identified a high level of stasis in occupational mobility at a pan-European scale of analysis, with some two-thirds returning to the same pre-migration occupational category; this is broadly comparable to the findings of Arif and Irfan (Citation1997) and El-Mallakh and Wahba (Citation2016) in a non-European context.

There are several reasons for this apparent stasis including the fact that those in the highest occupational and economic activity categories prior to migration cannot experience upward mobility in terms of the categories utilised in this analysis. Beyond this we can conjecture that intra-European young adult migration is likely to provide informal competences rather than formal qualifications (Janta et al. Citation2021; Williams and Baláž Citation2005). These are more likely to facilitate an individual to improve his or her position within an occupational category or become more employable, rather than transition to a substantially higher occupational category.

Employment changes were far more likely to be positive than negative. 27.0% of returnees experience upward occupational mobility whereas only 6.8% experience downward occupational shifts – the latter confirms the risks of downward mobility for young adult return migrants (Williams and Baláž Citation2014). The positive balance was even more striking in respect of economic activity, with 49.3% experiencing increased activity rates, while only 8.6% experience reduced economic activity after return. Any downward shifts in occupational status and economic activity level may be voluntary or reflect a period of readjustment to home-country labour market conditions as suggested by Martin and Radu (Citation2012) reflecting on their own analysis which was limited to one year after return.

Individuals may experience a variety of employment outcomes along the two axes of economic activity and occupational change. The single most likely outcome is of no change in either broad occupational category or level of economic activity (47.8%). If there are changes then the vast majority are likely to occur only on a single axis: 28.7% of the survey recorded these as positive, and 6.6% as negative changes in occupational mobility or economic activity. In terms of joint change across both axes: 13.0% of the survey were in a positive and 1.1% in a negative direction. It was unusual for respondents to report contradicting changes in occupational mobility and economic activity (2.8%). The need to carefully disentangle this array of changes along the two axes may partly explain the sometimes apparently contradictory findings about employment changes in the literature.

5.2. The determinants of employment mobility

Structural influences are evident in the migrants’ experiences of occupational mobility. Pre-migration occupation is the most important determinant on occupational mobility. All groups are more likely to experience greater upward than downward occupational mobility except professionals (for obvious reasons), with change most prominent in the lowest ranked (unskilled manual) occupations even after controlling for a range of other influences. In part, this may be due to having been the group who least fulfilled their employment potential before migration, and it was this frustration which (selectively) encouraged their migration. More positively, it may be argued that all young adult migrants are potentially knowledgeable, and have the capacity to learn, which by extension may contribute to eventual positive occupational outcomes (Williams Citation2006; Williams and Baláž Citation2005). A strong positive mobility with higher education is also observed for all return migrants (Martin and Radu Citation2012; Lados and Hegedűs Citation2016), suggesting that migration may be important for those with tertiary education who have been underperforming in their pre-migration occupations. To some extent this may be due to the experiences of those who are students or recently graduated – and may have worked temporarily in what can be termed ‘survival’ jobs. This may have given them an unusually high propensity to migrate, raising issues of selectivity and causality that are beyond the scope of this paper. Or they may have greater capacity to acquire new competences abroad, including language skills, that will facilitate upward mobility after return to jobs more commensurate with their qualifications.

The main determinants of changes to economic activity are education, pre-migration economic activity and civil status. There is an overwhelmingly strong likelihood that individuals leaving casual, seasonal or no form of economic activity will return to full-time employment.

Those that were separated (divorced or widowed) prior to migration return to economic activities that are half a rank lower and having children prior to migration is associated with an even greater reduction in activity rates (up to one whole rank). Previous research has shown that having children, or children reaching certain life cycle stages, plays a key role in return decisions (Dustmann Citation2003). Our modelling suggests that migration may have provided the resources to allow some individuals to return to lower activity levels, perhaps to have more quality time with their children, or to provide family care. This brings a more nuanced insight into the relationship between civil status and changes in activity rates compared to the limited extant research which focusses on relatively simpler categories of economic activity changes (Martin and Radu Citation2012; Coniglio and Brzozowski Citation2018). This raises questions about migration motivation and separation (Flowerdew and Al-Hamad Citation2004): if ‘escape’ from constraining social or economic circumstances is the driver of migration amongst those who are separated, then the decrease in their overall economic activity levels may be interpreted as exhibiting the risks associated with this strategy, or with ‘success’ in terms of migration having provided resources to depart from the labour market, at least temporarily, to undertake caring of others, especially their children. On the other hand, success in any labour market – home or abroad – is partially dependent on the availability of the childcare that is accessible to single separated parents.

Small yet significant gains in economic activity were reported by older returned migrants and men rather than women which broadly reflects the findings of Vlase (Citation2013) and Martin and Radu (Citation2012) on return migrants in general. We only observed weak associations between the age of returned migrants and gains in human capital: Occupational mobility increased by 0.12 ranks and economic activity increased by 0.21 ranks per 10-year increase in age. Migration channels appear to be of limited importance, although some benefits are gained as would be expected when plans are in part organised through company policy, and to a certain extent via student placement schemes, or recruitment agencies in destination countries; the limited significance of this factor may reflect the diversity of such migration channels.

5.3. The geography of employment mobility

Several geographical characteristics of the individual respondents appeared to have moderate influences on economic activity. Less favourable outcomes are reported for individuals that (1) grew up in rural locations, which resonates with extant knowledge that return migrants to rural areas are less able to utilise their skills than returnees to urban areas (King Citation1984, although commenting on a different migration period and age group); (2) returned to a country with higher levels of life expectancy (which may reflect other underlying socio-economic conditions), and (3) were born outside of the EU and have a settled status, suggesting that known persistent barriers faced by many third-country migrants to the EU are also evident in the experiences of those who undertake subsequent circular migration (Dustmann and Frattini Citation2011). Hierarchical structures within the multilevel models found neither the origin country nor macro-region (of return) to influence occupational mobility. This may be due to how international versus intra-national differences cancel each other out or – and this would be surprising – previous occupational underperformance and mobility do not have a territorial dimension.

However, there are prominent territorial effects for economic activity levels, including national differences. Hierarchical effects at a national level reveal that return migrants to Romania and Latvia tended to move up 0.5 more occupational ranks than their counterparts in southern or western European countries, suggesting disparities between the ‘old’ and ‘newer’ EU countries. EU accessions in 2004 (for A8 countries) and 2007 (for A2 countries) led to a large influx of Eastern European migrants reducing unemployment rates in their home countries – at the same time these ascension countries benefited from EU investment. Contrary to the findings of Martin and Radu (Citation2012), it seems that this group of young migrants often returned to full-time employment. Meanwhile, Southern European countries were hit particularly hard by the Great Recession of 2008 with youth unemployment in Spain and Italy respectively reaching rates of 48.3% and 40.3% (Eurostat Citation2016) – these economic hardships and an over-supply of higher-skilled individuals limit the opportunities for returnees.

Macro-regional (NUTS1) variations in the economic activity of returned migrants reveal a more favourable outcome for individuals returning to capital cities (and their hinterlands), reflecting the different regional labour market opportunities. The cities of Hamburg (DE), Frankfurt (DE), Munich (DE), Bucharest (RO), Madrid (ES), Stockholm (SE) and London (UK) are associated with higher economic activity levels. Some cities play a role of ‘magnets’ particularly for young individuals, and they include both established ‘creative’ cities and emerging regional hubs (Lulle, Janta, and Emilsson Citation2021).

6 Conclusions

This study represents one of the largest-scale and most comprehensive investigations of return migrants’ employment mobility. It constitutes the first attempt to analyse both occupational mobility and level of economic activity, and the relationship between these, combining macro and individual variables.

The findings indicate the complexity of the employment changes associated with international migration and return, discovering interactions in occupational mobility and economic activity. Most migrants return to the same broad occupational category as prior to migration, but approximately a half are likely to have experienced an increase in their economic activity level. This is particularly significant for those returning to Eastern Europe as opposed to those going home to Southern or Western European regions. The paper confirms that any employment changes are likely to be positive, but there are risks of downward shifts. There is a need to play closer attention to the relationships between occupational mobility and economic activity changes to improve our understanding of how return migration influences individual and regional economic potentials versus actual economic outcomes. The descriptive data indicate that previous occupations play an important mediating role in their experiences – in other words, there are important structural effects. These are evident in the innovative Bayesian multilevel models that we utilised. At the level of individual determinants, the models point to the complexity of the drivers of change, but education, and having a manual job pre-migration are particularly important for occupational mobility, as civil status and having children are for the economic activity shift. The migration experience itself, in terms of duration or type of destination country, has a limited role in determining outcomes after return.

Although this represents one of the more comprehensive quantitative analyses of the determinants of employment changes across the migration cycle, some reservations are important. First, employment changes have been measured across broad categories, which miss the nuanced but often important changes within these categories. Linked to this, any gains in economic activity may have been underreported following the exclusion of the ‘self-employed’ (<10% of the respondents), although this is expected to have a minimal impact on the overall findings. Secondly, the meaning of the upward and downward occupational mobility, and increased versus decreased levels of economic activity, must be interpreted carefully. Downward mobility may be due to a lack of opportunities or may represent desired outcomes for some individuals, where migration has provided resources to allow them reduced labour market engagement, perhaps for family care reasons. Thirdly, our research design and data set do not allow us to comment on the additionality effects of migration – whether similar employment changes would have been realised if they had not migrated. This is important given the selectivity of migration. Fourthly, due to the constraints of an already lengthy and broadly based questionnaire, we were not able to include any questions about employment experiences abroad which would have influenced employment after return. Finally, the returnees are at different stages of having returned to their home countries and, as Martin and Radu (Citation2012) have argued, it can take time to re-integrate into home country/region labour markets. Moreover, given the increasingly fluid and variegated nature of mobility (King and Christou Citation2011) return may be a temporary staging post in their migration histories and career development.

The paper has provided evidence to support the notion that migration can have positive economic outcomes, especially for individuals, and territorially, although there is also evidence of urban-rural and capital city differentials in the latter. This highlights the need for targeted rather than broad-brush policies to maximise positive economic outcomes. The findings also highlight the complex drivers of individual outcomes, and the consequent need to understand the limitations of policy interventions.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (38.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anacka, M., and A. Fihel. 2012. “Return Migration to Poland in the Post Accession Period.” In EU Labour Migration in Troubled Times: Skills Mismatch, Return and Policy and Policy Responses, edited by B. Galgóczi, J. Leschke, and A. Watt, 143–167. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Arif, G. M., and M. Irfan. 1997. “Return Migration and Occupational Change: The Case of Pakistani Migrants Returned from the Middle East.” The Pakistan Development Review 36 (1): 1–37.

- Barcevičius, E. 2016. “How Successful Are Highly Qualified Return Migrants in the Lithuanian Labour Market?” International Migration 54 (3): 35–47.

- Basilio, L., T. K. Bauer, and A. Kramer. 2017. “Transferability of Human Capital and Immigrant Assimilation: An Analysis for Germany.” Labour (committee. on Canadian Labour History) 31 (3): 245–264.

- Carletto, C., and T. Kilic. 2011. “Moving up the Ladder? The Impact of Migration Experience on Occupational Mobility in Albania.” Journal of Development Studies 47 (6): 846–869.

- Cassarino, J. P. 2004. “Theorising Return Migration: The Conceptual Approach to Return Migrants Revisited.” International Journal on Multicultural Societies 6 (2): 253–279.

- Coniglio, N. D., and J. Brzozowski. 2018. “Migration and Development at Home: Bitter or Sweet Return? Evidence from Poland.” European Urban and Regional Studies 25 (1): 85–105.

- Cook, J., P. Dwyer, and L. Waite. 2011. “The Experiences of Accession 8 Migrants in England: Motivations, Work and Agency.” International Migration 49 (2): 54–79.

- Denwood, M. 2016. “. Runjags. An R Package Providing Interface Utilities, Model Templates, Parallel Computing Methods and Additional Distributions for MCMC Models in JAGS.” Journal of Statistical Software 71 (9): 1–25.

- Staniscia, B., L. Deravignone, B. González-Martín, and P. Pumares. 2021. “Youth Mobility and the Development of Human Capital: Is There a Southern European Model?” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (8): 1866–1882.

- Duleep, H. 1994. “Social Security and the Emigration of Immigrants.” Social Security Bulletin 57 (1): 37–52.

- Dustmann, C. 2003. “Children and Return Migration.” Journal of Population Economics 16 (4): 815–830.

- Dustmann, C., and T. Frattini. 2011. Immigration: The European experience. Centro Studi Luca d’Agliano Development Studies Working Paper (326).

- Dustmann, C., and O. Kirchkamp. 2002. “The Optimal Migration Duration and Activity Choice After re-Migration.” Journal of Development Economics 67 (2): 351–372.

- Dustmann, C., and Y. Weiss. 2007. “Return Migration: Theory and Empirical Evidence from the UK.” British Journal of Industrial Relations 45 (2): 236–256.

- El-Mallakh, N., and J. Wahba. 2016. Upward or downward: Occupational mobility and return migration. ERF Working Papers (No. 1010).

- Eurostat. 2016. European Semester Thematic Factsheet: Youth Unemployment. Accessed May 20, 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/european-semester_thematic-factsheet_youth_employment_en.pdf.

- Flowerdew, R., and A. Al-Hamad. 2004. “The Relationship Between Marriage, Divorce and Migration in a British Data set.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 30 (2): 339–351.

- Forschner, Smoliner S. M., and J. Nova. 2012. Re-turn. Comparative report on re-migration trends in Central Europe. http://www.iom.cz/files/comparative_Report_on_ReMigration.pdf.

- Galgóczi, B., J. Leschke, and A. Watt. 2012. “EU Labour Migration in Troubled Times.” In EU Labour Migration in Troubled Times: Skills Mismatch, Return and Policy Responses, edited by B. Galgóczi, J. Leschke, and A. Watt, 1–44. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Galwey, N. 2007. Introduction to Mixed Modelling: Beyond Regression and Analysis of Variance. London: John Wiley & Sons.

- Ganzeboom, H. B., and D. J. Treiman. 1996. “Internationally Comparable Measures of Occupational Status for the 1988 International Standard Classification of Occupations.” Social Science Research 25 (3): 201–239.

- Gelman, A. 2007. “Struggles with Survey Weighting and Regression Modeling.” Statistical Science 22 (2): 153–164.

- Gelman, A., and J. Hill. 2006. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gelman, A., and D. Rubin. 1992. “Inference from Iterative Simulation Using Multiple Sequences.” Statistical Science 7: 457–511.

- Gill, N., and P. Bialski. 2011. “New Friends in new Places: Network Formation During the Migration Process among Poles in the UK.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 42 (2): 241–249.

- Grabowska, I., and A. Jastrzebowska. 2019. “The Impact of Migration on Human Capacities of two Generations of Poles.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (8): 1829–1847.

- Grabowska-Lusińska, I., and M. Okólski. 2009. Emigracja Ostatnia? Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar.

- Hagan, J. M., and J. Wassink. 2020. “Return Migration Around the World: An Integrated Agenda for Future Research.” Annual Review of Sociology 46: 533–552.

- Hargittai, H. 2020. “Potential Biases in Big Data: Omitted Voices on Social Media.” Social Science Computer Review 38 (1): 10–24.

- Hox, J. 1998. “Multilevel Modelling: When and why.” In Classification, Data Analysis, and Data Highways, edited by I. Balderjahn, R. Mathar, and M. Schader, 147–154. New York: Springer Verlag.

- Janta, H., C. Jephcote, A. M. Williams, and G. Li. 2021. “Returned Migrants Acquisition of Competences: The Contingencies of Space and Time.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (8): 1740–1757.

- King, R. 1984. “Population Movement: Emigration, Return Migration and Internal Migration.” In Southern Europe Transformed, edited by A. M. Williams, 145–178. London: Harper and Row.

- King, R. 2018. “Theorising new European Youth Mobilities.” Population, Space and Place 24 (1): e2117.

- King, R., and A. Christou. 2011. “Of Counter-Diaspora and Reverse Transnationalism: Return Mobilities to and from the Ancestral Homeland.” Mobilities 6 (4): 451–466.

- King, R., A. Findlay, and J. Ahrens. 2010. International Student Mobility Literature Review. Bristol: Report to HEFCE.

- King, R., and A. M. Williams. 2018. “Editorial Introduction: New European Youth Mobilities.” Population, Space and Place 24 (1): e2121.

- Masso, J., L. M. Kureková, M. Tverdostup, and Z. Žilinčíková. 2018. “What are the Employment Prospects for Young Estonian and Slovak Return Migrants?” In Youth Labor in Transition, 461–500. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lados, G., and G. Hegedűs. 2016. “Returning Home: An Evaluation of Hungarian Return Migration.” Hungarian Geographical Bulletin 65 (4): 321–330.

- Lulle, A., and L. Buzinska. 2017. “Between a ‘Student Abroad’ and ‘Being from Latvia’: Inequalities of Access, Prestige, and Foreign-Earned Cultural Capital.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (8): 1362–1378.

- Lulle, A., H. Janta, and H. Emilsson. 2021. “Introduction to the Special Issue: European Youth Migration: Human Capital Outcomes, Skills and Competences.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (8): 1725–1739.

- Lundborg, P. 2013. “Refugees’ Employment Integration in Sweden: Cultural Distance and Labor Market Performance.” Review of International Economics 21: 219–232.

- Martin, R., and D. Radu. 2012. “Return Migration: The Experience of Eastern Europe.” International Migration 50 (6): 109–128.

- Mytna Kureková, L., and Z. Žilinčíková. 2020. “Determinants of Successful Labour Market Reintegration for Highly Educated Return Migrants in Slovakia.” Sociológia (Sociology) 52 (6): 624–647.

- ONS (Office for National Statistics). 2010. Standard Occupational Classification 2010, Volume 2: The Coding Index. Surrey: Office of Public Sector Information.

- Palovic, Z., H. Janta, and A. M. Williams. 2021. “In Search of Global Skillsets: Manager Perceptions of the Value of Returned Migrants and the Relational Nature of Knowledge.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (8): 1793–1810.

- Pratsinakis, M., R. King, C. L. Himmelstine, and C. Mazzilli. 2020. “A Crisis-Driven Migration? Aspirations and Experiences of the Post-2008 South European Migrants in London.” International Migration 58 (1): 15–30.

- Saarela, J., and D. O. Rooth. 2012. “Uncertainty and International Return Migration: Some Evidence from Linked Register Data.” Applied Economics Letters 19 (18): 1893–1897.

- Sjaastad, L. 1962. “The Costs and Returns of Human Migration.” Journal of Political Economy 70 (5): 80–93.

- Straubhaar T. 2000. International Mobility of the Highly Skilled: Brain Gain, Brain Drain or Brain Exchange. HWWI A Discussion Paper 88, Hamburg.

- Tverdostup, T., and J. Masso. 2016. “The Labour Market Performance of Young Return Migrants After the Crisis in CEE Countries.” Baltic Journal of Economics 16 (2): 192–220.

- Van-der-Heijden, B. I. M. 2002. “Individual Career Initiatives and Their Influence upon Professional Expertise Development Throughout the Career.” International Journal of Training and Development 6: 54–79.

- Vlase, I. 2013. “My Husband is a Patriot!’: Gender and Romanian Family Return Migration from Italy.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39 (5): 741–758.

- Wasserstein, R., and N. Lazar. 2016. “The ASA's Statement on p-Values: Context, Process, and Purpose.” The American Statistician 70 (2): 129–133.

- White, A. 2014. “Polish Return and Double Return Migration.” Europe-Asia Studies 66 (1): 25–49.

- Williams, A. M. 2006. “Lost in Translation? International Migration, Learning and Knowledge.” Progress in Human Geography 30 (5): 588–607.

- Williams, A. M., and V. Baláž. 2005. “What Human Capital, Which Migrants?” Returned Skilled Migration to Slovakia from the UK. International Migration Review 39 (2): 439–468.

- Williams, A., and V. Baláž. 2008. International Migration and Knowledge. London: Routledge.

- Williams, A., and V. Baláž. 2014. Migration, Risk and Uncertainty. London: Routledge.

- Williams, A. M., C. Jephcote, H. Janta, and G. Li. 2018. “The Migration Intentions of Young Adults in Europe: A Comparative, Multilevel Analysis.” Population, Space and Place 24 (1): e2123.

- Zwysen, W. 2019. “Different patterns of labor market integration by migration motivation in Europe: the role of host country human capital.” International Migration Review 53 (1): 59–89.