ABSTRACT

Compared to individuals without a migration background, the second generation seems more likely to possess the type of skills, values and transnational ties that facilitate international moves. In other words, ‘mobility capital’ transmitted from parents of migrant origin to their children may increase the likelihood of emigration among the second generation. Yet so far this expectation has not been tested empirically. To address this knowledge gap, this study analyses emigration patterns and determinants of the Western European second generation born in the Netherlands between 1987 and 1992 using longitudinal data from the Dutch population registers. The study addresses whether the second generation is more likely to emigrate during early adulthood as compared to peers without a migration background, and whether this difference is related to having immigrant parents or follows from other background characteristics. The results show that the Western European second generation has a higher chance to emigrate from the Netherlands than individuals without a migration background, and that this difference remains when taking socio-economic indicators, current individual demographics, and household characteristics at age 15 into account. As such, the study is among the first to identify having a second-generation migration background as an important predictor of international migration.

1. Introduction

In Western European countries the number of individuals born to immigrant parents has been growing, and a rising share of this so-called ‘second generation’ has reached adulthood over the past decades. Linked to these developments, a growing body of literature has studied the impact of having immigrant parents on outcomes in the public and private sphere later in life. Prior research has frequently addressed the social mobility of the second generation, that is, their developments in the educational system or on the labour market (e.g. Hammarstedt Citation2009; Hermansen Citation2016; Laurijssen and Glorieux Citation2015). However, we know much less about the mobility of the second generation in geographical terms, that is, their international migration behaviour. This gap in the literature is unfortunate because immigrant parents at least to some extent seem to pass transnational ties on to their children. Having immigrant parents likely fosters transnational behaviour, as the second generation is raised and socialised in a context where the culture and country of origin of the parents, as well as friends and relatives residing abroad, typically play an important role (Groenewold and De Valk Citation2017). Due to this ‘mobility capital’ acquired from parents of migrant origin, one may expect a higher chance of emigration among the second generation as compared to peers without a migration background. In other words, the family’s history of migration may be an important predictor of a person’s own migration potential. Yet so far, this expectation is seldom tested empirically.

An exception is a recent study by De Jong (Citation2021), who investigated the likelihood of emigration of the Turkish second generation from the Netherlands. In this study, the emigration rate was more than twice as high for the Turkish second generation than for their peers without immigrant parents. As one of the first to investigate actual migration behaviour rather than migration intentions, this study importantly contributed to the broader literature on the second generation in Western European societies, which predominantly focused on the children of non-Western immigrants, those of Turkish descent in particular. However, as most members of the Turkish second generation are born to low-skilled labour migrants, they do not only differ from their peers without a migration background in terms of their mobility capital, but also in terms of their social and economic capital (e.g. Crul and Doomernik Citation2003). Such structural inequalities complicate a comparison of the migration potential between these groups. Furthermore, higher costs of migration over long distances, as well as border restrictions that regulate moves between Turkey and European countries may create barriers for the Turkish second generation to emigrate to the country of origin of their parents, even if they desire to do so (e.g. Fokkema Citation2011). Finally, as immigrant parents from other origin countries may have moved for different reasons compared to first generation Turkish immigrants, their offspring may become mobile for different reasons as well. In other words, in order to expand our knowledge on the impact of having immigrant parents on one’s own likelihood to migrate, it is essential to also study the emigration behaviour for other origin groups within the second generation.

Another substantial, though much less studied group within the second generation consists of the children of European immigrants. Many Western European countries have a long-established history of migration with their neighbouring countries. With the formation of the European Economic Community (EEC) and later the European Union (EU), agreements for international trade were established, and the freedom to work and reside in another member state became one of the fundamental principles of the EU. In line with these objectives, international moves between EU member states have been labelled ‘mobility’ rather than ‘migration’ (e.g. Koelet, Van Mol, and De Valk Citation2017). Related to their right to freedom of movement, EU citizens residing in another EU member state have remained largely unaddressed by studies on immigrant integration. Furthermore, compared to non-Western immigrants, EU migrants and their children resemble the majority population of the host country more closely in terms of their socio-economic position. These factors explain why previous research has mainly focused on the second generation with a non-Western background. Yet for similar reasons, the Western European second generation provides a particularly interesting case to study the impact of having immigrant parents and related mobility capital on international migration behaviour. After all, a greater resemblance to the Dutch majority population in terms of mobility rights, chosen destinations and position in society allows for a more straightforward comparison of their emigration behaviour. Further highlighting the relevance of studying this group, in the Netherlands, the share of the population who emigrated at adult ages was found to be as high for the largest Western-European groups (i.e. Belgium, Germany and the UK) as for the largest non-Western groups (i.e. Morocco and Turkey) (De Jong, Wachter, and Dieleman Citation2020). While qualitative studies have described experiences of ‘counter diasporic migration’ by descendants of specific European migrant groups (King and Christou Citation2014; Pelliccia Citation2017; White and Goodwin Citation2021), so far, the emigration behaviour of the Western European second generation has not been systematically compared with that of the majority population.

This study innovatively investigates the emigration patterns and determinants of the Western European second generation born in the Netherlands using unique longitudinal data from the Dutch population registers. We aim to understand whether the second generation is more likely to emigrate during early adulthood as compared to peers without a migration background, and if so, to disentangle whether this difference seems indeed related to having immigrant parents, or whether it can be explained from other socio-economic background characteristics. This way, the study provides novel insights on whether ‘mobility capital’, like other forms of capital (e.g. social, human capital), is transmitted across generations.

2. Theory

2.1. Mobility and migration-specific capital

Migration scholars often acknowledge the importance of ‘migration-specific capital’, that is, the abilities and resources that migrants mobilise or acquire during their migration trajectory, and that facilitate subsequent international moves (e.g. Deléchat Citation2001). Through movement, migrants are expected to accumulate the technical and cognitive skills that are useful for crossing borders again, or to cross them in an increasingly productive manner. This way, previous migration experiences may lower the perceived constrains and costs of migration and increase the willingness to move (Huinink, Vidal, and Kley Citation2014).

Comparable to the notion of migration-specific capital, the field of mobilities studies defines ‘mobility capital’ as skills or assets that allow people to cross borders rather easily, to feel comfortable and carry out activities in different places, and to return again (Clark and Lisowski Citation2018; Moret Citation2020). Mobility capital enables people to pursue specific cross-border mobility practices that bring advantages for themselves or their families (Moriarty et al. Citation2015). Important to this definition, mobility capital allows people to cross national borders when doing so appears worthwhile, but also to remain immobile by choice (Moret Citation2020).

2.2. Mobility capital of the second generation

So far, the concepts of migration-specific and mobility capital have been mainly applied to individuals with prior migration experience. In this respect, the use of these concepts differs from other forms of capital, like human and social capital, where the literature assumes a transfer of individual abilities, traits, behaviours and outcomes from parents to their children, known as ‘intergenerational transmission’ (e.g. Lundborg, Nordin, and Rooth Citation2018; Weiss Citation2012). Following the literature on intergenerational transmission, in this study we argue that individuals with a second-generation migration background – before ever deciding on migration themselves – share in the mobility capital of their immigrant parents.

The literature offers several cues in support of this claim. To start with, during their upbringing, the second generation is often exposed to the language and culture of the country of origin of their parents (e.g. Van Mol and De Valk Citation2018). The ability to manage several cultural repertoires at once may contribute to a transnational lifestyle, thereby influencing the mobility patterns of the second generation (Levitt Citation2009). Second, through regular contact with and visits to family and friends residing in the parents’ country of origin, the second generation often has access to social networks abroad (Groenewold and De Valk Citation2017). Third, and while these studies focused on internal rather than international moves, the literature on residential mobility has demonstrated that childhood moves generally increase the likelihood of residential mobility in adulthood (see Bernard and Vidal Citation2020; Myers Citation1999). The notion that ‘moves during childhood accustom individuals to moving in a way that raises their likelihood to become mobile later in life’ suggests that mobility is to some extent learned behaviour (Bernard and Vidal Citation2020). Here we take this reasoning one step further and argue that even prior to migrating themselves the second generation may have learned from their parents how to negotiate the complexity of leaving and entering social contexts. Finally, one may expect the second generation to grow up in families who are positively predisposed towards migration (see Cairns, Growiec, and Smyth Citation2013). The family’s history of migration may increase awareness of mobility as a valued personal competence, encouraging the second generation to pursue mobility opportunities themselves (Moriarty et al. Citation2015). To sum up, compared to individuals without a migration background, the second generation seems more likely to be introduced to mobility-related capital that facilitates international moves, as well as ‘tastes’ that render living abroad more attractive (Gundel and Peters Citation2008). We therefore expect to find a higher probability of emigration among the second generation as compared to individuals without a migration background.

2.3. A focus on the Western European second generation

In testing this hypothesis, we strategically focus on the second generation with a Western European background for several reasons. First, in the Netherlands, a person’s citizenship status is primarily determined by the citizenship status of the parents (Labussière and Vink Citation2020). Consequently, children born to non-Western immigrants typically inherit the non-Western nationality of their parents, while children born to EU citizens generally have a European passport. Prior research has identified a person’s residence status as an important form of mobility capital, as it affects the degree of control a person has over his or her own cross-border movements (Hoon, Vink, and Schmeets Citation2020; Moret Citation2020). This is particularly relevant in the context of the EU, where a national passport also functions as a European passport (Hoon, Vink, and Schmeets Citation2020). EU citizenship not only guarantees re-entry in the Netherlands after a stay abroad; it also provides the right to move to and reside or work in any part of the EU. Based on these citizenship rights, the potential to become mobile within the EU is therefore quite comparable for the European second generation and their Dutch peers without a migration background, while greater differences exist between these groups and the non-Western second generation. This greater comparability in terms of mobility rights forms a first important reason for this study to focus on the Western European second generation.

As a further and partly related reason, the mobility capital transmitted by immigrant parents to their children is likely to some extent specific to their own country of origin and may especially facilitate a move to this country rather than any other destination. Yet for the non-Western second generation, emigration from the Netherlands to the country of origin of their parents typically represents a move from a more, to a less developed country. While the second generation with a non-Western background may have the desire to emigrate to the country of origin of their parents (e.g. Bettin, Cela, and Fokkema Citation2018; Fokkema Citation2011), limited economic opportunities in these countries may prevent them from actually doing so (Çelik and Notten Citation2014). Focusing on the Western European second generation circumvents this issue, since Western European countries are comparable to the Netherlands regarding their level of economic development. Further contributing to a meaningful comparison, Western European countries are also the destinations most frequently selected by Dutch emigrants without a migration background (De Jong, Wachter, and Dieleman Citation2020).

Finally, according to Moriarty et al. (Citation2015), mobility capital entails the right combination of economic and social resources – that is, practical knowledge on how to be mobile plus financial support – for obtaining successful labour market outcomes. Access to mobility has been linked to socio-economic background as economic capital and social ties play a crucial role in determining who is capable of moving (e.g. Carling and Schewel Citation2018; De Haas Citation2010). In fact, the option of becoming mobile to improve one’s life chances has been recognised as a key indicator of inequality in a globalised world (Beck Citation2007). In Western European societies, Western European immigrants and their children typically resemble the majority population more closely in terms of their socio-economic position than the non-Western first and second generation. A focus on the Western European second generation therefore better allows to disentangle the impact of having immigrant parents on a person’s decision to emigrate from differences that purely stem from socio-economic inequalities.

2.4. Additional indicators of migration potential

To investigate the impact of having immigrant parents on a person’s likelihood to emigrate, we wish to capture to what extent differences in emigration rates of the second generation and individuals without a migration background stem from other structural factors that may influence a person’s migration potential. Historically, acquiring mobility capital has been used as a strategy of privileged families to reinforce their socio-economic position (Murphy-Lejeune Citation2002). With ongoing trends of individualisation and globalisation, a period of living, studying or working abroad when young has become an increasingly widespread part of the transition to adulthood in more developed countries (Cairns Citation2014; Conradson and Latham Citation2005; Frändberg Citation2014). Still, one can expect the chance of emigration to be higher among individuals who grew up in households with comparatively the highest income levels. Furthermore, especially young, highly skilled EU citizens are geographically flexible and financially less restrained, and are frequently characterised as the ‘winners’ of globalisation and European integration (Brandle Citation2020; Kriesi et al. Citation2008). We hence expect the chance of emigration over early adulthood to be higher among individuals with the highest levels of education.

Another factor that potentially plays a role in mobility decisions is geographical location. Living close to a national border may increase opportunities for a transnational lifestyle and may facilitate cross-border movements (Gielis Citation2009). Supporting this idea, emigration from the Netherlands to neighbouring countries Germany and Belgium appears to occur more often among people living in the Dutch border regions as compared to those living in other areas (see Graef and Mulder Citation2003; Van Houtum and Gielis Citation2006). The chance of emigration may also be higher for individuals living in the largest, most culturally diverse cities of the Netherlands, given that the level of diversity has been found to affect the volume of migration (Lee Citation1966). Considering these aspects of a person’s place of residence is particularly relevant for this study as previous research has indicated that Western European immigrants are in fact clustered in the border regions and most densely populated areas of the Netherlands (van Wissen and Heering Citation2014). As this clustering of the first generation may have an impact on the place of residence of the second generation later in life, we include information on both a person’s current place of residence, as well as their place of residence at age 15.

Finally, the decision to emigrate rather than to stay is likely influenced by a person’s current circumstances in the public and the private sphere. Regarding the former, one may expect that individuals who are unemployed will be more likely to leave the Netherlands than those who are employed, due to weaker ties to the country (e.g. Bettin, Cela, and Fokkema Citation2018). What is more, within the EU, arrangements like the ERASMUS programme have aimed to stimulate mobility among students in higher education (Van Mol Citation2019). One may therefore also expect a higher chance of emigration among individuals who are enrolled in higher levels of education in the Netherlands. In the private sphere, a person’s household composition has been found to affect the likelihood of emigration. More specifically, prior research has illustrated that living with a partner or children tends to connect people to their current place of residence, thereby lowering the preparedness to emigrate (e.g. Cairns and Smyth Citation2011). In the analyses we take each of these factors into account.

3. Data and methods

3.1. Data

For this study we use longitudinal, full population register data from the System of Social Statistical Datasets (SSD) compiled by Statistics Netherlands. The SSD consists of several registers that have been linked to the Dutch municipal population registers (Bakker, Van Rooijen, and Van Toor Citation2014). For every official inhabitant of the Netherlands the SSD covers a broad range of demographic and socio-economic indicators including age, position on the labour market, household composition and migration. To investigate the chance of emigration during early adulthood we focus on individuals born in the Netherlands between 1987 and 1992. The data allow us to follow these individuals from the year they turned 18 years old until the end of 2017, when they have reached ages between 25 and 30 years old.

3.2. Study population

To test the hypotheses, we focus on individuals who were born in the Netherland to at least one parent who was born in Belgium, Germany, France, or the United Kingdom (UK).Footnote1 We refer to this group as the Western European second generation. Although one can additionally think of Austria, Ireland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Monaco, and Switzerland as Western European countries, in the Netherlands the second generation from each of these origins is fairly small. we therefore chose to focus on the four largest groups, who together constitute the majority (around 67 per cent) of the European second generation in the Netherlands. What is more, these countries are rather comparable in terms of their migration history with, and geographical distance to the Netherlands.

Previous studies within the Dutch context have shown that it is not uncommon for Western European immigrants to have a Dutch partner (Van Mol, De Valk, and Van Wissen Citation2015; van Wissen and Heering Citation2014). In turn, it is likely that part of the Western European second generation in the study population will have one Dutch parent. In comparison with individuals whose parents were both born abroad, this group may be more strongly connected to the Netherlands and may therefore be less likely to emigrate. Where possible, in the analyses we therefore distinguish individuals with only one immigrant parent from those whose parents were both born abroad. As comparison group we include individuals born in the Netherlands without immigrant parents.

3.3. Dependent variable: emigration

In the Netherlands, residents are expected to officially deregister at a Dutch municipality if they expect to live outside the Netherlands for at least eight months. The population registers thus contain reported information on the timing of emigration, as well as the country of destination. In the analyses, we use this information to capture emigration. Unfortunately, in practice not everyone who leaves the country to live elsewhere actively deregisters at their Dutch municipality. In this study, we therefore assume that individuals whose whereabouts are unknown to the Dutch authorities for more than twelve months have left the country and treat this group as emigrants in our analyses. For the purpose of this study, we focus on the first international move at adult ages, rather than possible subsequent moves.

3.4. Independent variables

As motivated above, in the analyses we wish to distinguish the impact of having immigrant parents from other background characteristics that may affect a person’s likelihood to emigrate. For this we incorporate information on a person’s situation while growing up, as well as time-varying indicators since turning 18 years old. As a measure of the financial resources available within the household during early adolescence, we include information on the net household income at age 15. We distinguish households by their place in the income distribution (1 = ‘percentiles below 50’; 2 = ‘percentiles 50–70’; 3 = ‘percentiles 70–80’; 4 = ‘percentiles 80–90’; 5 = ‘percentiles above 90’). Following our theoretical line of argumentation, we account for the role of living close to the borders or in the larger cities (most densely populated areas of the Netherlands) by including information on the place of residence before turning 18 years old. First, we differentiate individuals who lived in a Dutch border region at age 15 (1 = yes; 0 = no). Border regions are defined as the regions at NUTS 3 level (or ‘COROP regions’) that are located directly at the German or Belgian border. Second, we distinguish individuals who at age 15 were living in the most densely populated areas of the Netherlands (1 = more than 2500 households per km2, 0 = 2500 or less households per km2).

The chance of emigration likely also depends on a person’s current socio-economic position, place of residence and household composition. Different from the previously described variables, these indicators may vary within an individual over the observed years and are therefore included in the models as time-varying factors. Regarding socio-economic position, we consider a person’s main occupation. The impact of being either employed, unemployed or enrolled in education likely depends on the highest level of education that a person has completed. For instance, students in tertiary education may be more likely to emigrate as part of their study as compared to those enrolled in lower levels of education. Also regarding being unemployed, the impact on emigration may vary depending on the level of education. Instead of entering main occupation and highest level of education in to model as two separate variables, we therefore combine the two dimensions into a single time-varying variable, which distinguishes the following six categories: (1) Student, enrolled in tertiary levels of education; (2) Student, enrolled in lower than tertiary levels of education; (3) Employed, completed tertiary levels of education; (4) Employed, completed less than tertiary levels of education; (5) Unemployed, completed tertiary levels of education; (6) Unemployed, completed less than tertiary levels of education. To investigate the impact of a person’s current place of residence, we include time-varying variables indicating whether a person lived in the border regions or most densely populated areas of the Netherlands (same coding of regions as above). In this coding, we included main occupation as measured on the first day of the respective year. To capture a person’s household composition, the time-varying variables ‘partner’ and ‘child’ indicate for each year whether an individual is married or in a registered partnership, and has a child (1 = yes, 0 = no). Finally, in all models we control for differences between men and women (male = 1; female = 0).

3.5. Analytical strategy

For the analyses we use an event-history setup which allows to analyse the time to an event – in this case emigration. Event-history models are less sensitive to right-censoring or skewed distributions in the dependent variable than alternative estimation methods, such as logistic and multinomial regression models (Allison Citation2014). The process time for emigration starts at age 18 and the population at risk consists of individuals born in the Netherlands between 1987 and 1992. Individuals are right-censored at the end of the observation period, which is December 2017.

To include time-varying effects in the models the data have to be restructured to a long format, with the rows representing person-years rather than persons. As this transformation increases the number of cases significantly, we are unable to perform the analyses on the full study population of over 800 thousand individuals. Instead, prior to restructuring the data, we drew a ten per cent random sample of the population without a migration background, while retaining the full Western European second generation. We use frequency weights in the analyses to account for this oversampling of the second generation. We report the findings with robust standard errors to correct for a clustering of person-years within individuals.

3.6. Missing values

For a small share of the person-years (1.6%), information on highest level of completed education – necessary to construct the variable capturing socio-economic status – was missing from the data. To solve this issue, we imputed missing values as much as possible with information on highest level of completed education from either the previous or next year. Individuals who after these adjustments still showed missing values on level of completed education for one or more years were excluded from the analyses (N = 2,169), as well as individuals with missing values on main occupation (N = 118), current place of residence (N = 811), household income at age 15 (N = 1,203) and place of residence at age 15 (N = 67). Missing values occurred more often among individuals who emigrated over the observation period: around one in five individuals with missing values emigrated. Removing cases with missing values resulted in the final study sample of 16,493 persons with and 75,521 without a migration background in the analyses.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive statistics

The German second generation formed the largest share of the Western European second generation in the study population (N = 7,223 or 44%), followed by the Belgian (N = 4,036 or 24%), and British second generation (N = 3,675 or 22%). The French second generation was the smallest of the four Western European origin groups included in this study (N = 1,559 or 9%). Background characteristics of our study population without, and those with one and two immigrant parents are described in in the Appendix.

4.2. Prevalence and timing of emigration

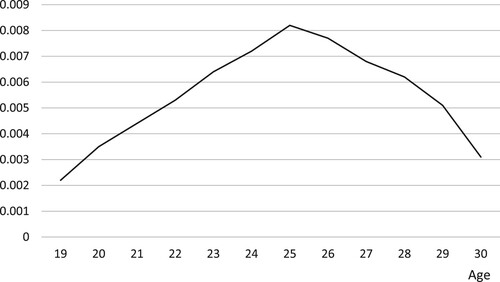

presents the prevalence of emigration over early adulthood as observed within the study population, that is, the Dutch majority group and the Western-European second generation born between 1987 and 1992. While the data signal that the emigration hazard peaks at age 25 and decreases with higher agers, the sharp turnaround at age 25 is in part an artifact of us being able to follow the study population until the end of 2017, when they have reached ages between 25 and 30 years old.

Figure 1. Hazard rate of observed emigration behaviour over early adulthood of the study population.

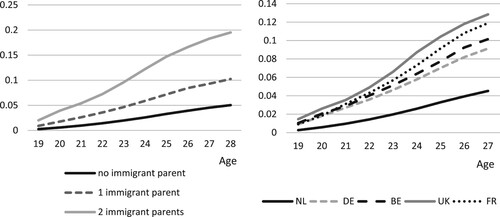

Between 2001 and 2017, 4.6 per cent of the individuals born to two Dutch parents emigrated from the Netherlands during early adulthood. Over the same years, 8.9 per cent of the second generation with one immigrant parent emigrated, and 14.1 per cent of those with two immigrant parents. presents the survival estimates by number of immigrant parents (left panel) and migration background (right panel). In line with our theoretical argumentation, the data show a higher likelihood of emigration during early adulthood for the Western European second generation than for their Dutch peers. The risk of emigration is highest among individuals with two foreign-born parents, and lowest among individuals without immigrant parents. Within the Western European second generation the highest risk of emigration is observed for individuals born to British parents, and the lowest for individuals born to German parents.

Figure 2. Survival estimates for emigration over early adulthood by number of immigrant parents (left) and migration background (right).

Within our study population, 75 per cent of the emigrants of the Western-European second generation moved to a European destination, compared to 64 per cent of emigrants of the Dutch majority population. While both groups thus often chose a European destination, a substantial share of emigrants of the second generation moved to the country of origin of (one of) their parents, indicating greater familiarity with their destination: 39 per cent of the emigrants with one immigrant parent, and 48 per cent of the emigrants with two immigrant parents. As this paper focuses on a comparison of the Western European second generation with individuals of the majority population, in the analyses we do not group emigrants by type of destination country though (i.e. parental home country vs other destination), since a grouping of this sort is relevant nor possible for individuals without immigrant parents.

4.3. Results from the event-history models

In the next sections we test our expectation that the second generation has a higher chance of emigration as compared to their peers without immigrant parents. provides the results from the event history models. The first model (column 1) clearly shows a higher probability of emigration for the second generation as compared to peers without a migration background, especially when both parents were born abroad. Yet as discussed above, the groups may differ with respect to other observable characteristics that relate to the probability of emigration. To account for such composition effects, we continue by introducing household characteristics at age 15 and current socio-economic, geographical, and demographic indicators to the model. As a person’s current geographical and socio-economic position may be influenced by his or her situation while growing up, we enter these sets of variables stepwise to get a clearer grasp on how recent and past conditions affect the likelihood to emigrate.

Table 1. Results from event history models for emigration over early adulthood.

4.3.1. Background characteristics at age 15

In the second model (column 2, ) we added information on the financial situation of the household and place of residence at age 15. The likelihood of emigration is highest among individuals who grew up in households with comparatively the highest and lowest income levels. This is in line with previous studies investigating the role of economic factors in migration decisions, where emigrants are generally found at both ends of the income distribution (e.g. Bijwaard and Wahba Citation2014). The likelihood of emigration was further higher among those who grew up in border regions. We do not find a significant impact of population density of the place of residence at age 15 on the probability of emigration.

4.3.2. Current circumstances

In the full model (column 3, ) the time-varying variables capturing a person’s current situation are included. The probability of emigration is clearly higher among individuals who are enrolled in tertiary levels of education than among individuals who are enrolled in lower levels of education, or those who are employed in the Netherlands. This finding indicates that student mobility forms an important type of emigration over early adulthood. However, the chance of emigration is even higher among the unemployed, in particular the highly skilled.

The model further shows a higher chance of emigration among individuals who currently live in border regions. After including the effect of currently living in a border region, the effect of living in a border region at age 15 no longer reaches statistical significance. The interplay of these two variables can be explained as a large share of the individuals who grew up in border regions still lives there over adulthood. The model indicates that currently living near the Dutch border has a stronger impact on the likelihood of emigration than growing up in such environment.

The chance of emigration is also higher among individuals who currently live in the most densely populated areas of the Netherlands. However, once population density of the place of residence at adult ages is added to the model, we observe a lower chance of emigration among those who lived in the most densely populated areas at age 15. These findings seem to indicate that especially individuals who currently live in the most densely populated areas, yet did not grow up there, are more likely to emigrate. One may think of different explanations for this finding. For instance, a move to the most densely populated areas since age 15 may signal a preference for a more culturally diverse or cosmopolitan environment, which in turn may be associated with a higher likelihood of moving abroad. Furthermore, and although the models do take level of education into account, a move to the largest cities of the Netherlands may occur more often among the higher educated, who frequently move there for study or work (Venhorst, Van Dijk, and Van Wissen Citation2010). One may also interpret this result more broadly as a mobility effect, that is, individuals who are prepared to move internally may be more willing to move internationally as compared to those who never moved (Schewel Citation2020). In any case, the findings indicate that big cities have an important role as stepping stones in international migration, a pattern which has been recognised in the migration literature as one of the ‘laws’ of migration (Lee Citation1966), yet is seldom considered for developed origin contexts.

Finally, the model captures the impact of current household characteristics. Very few individuals within the study population entered a marriage or registered partnership and had a child over the years of observation. Nevertheless, we can still observe that those who did experience these transitions were less likely to emigrate than those who did not, like we expected.

4.4. Separate model by number of immigrant parents

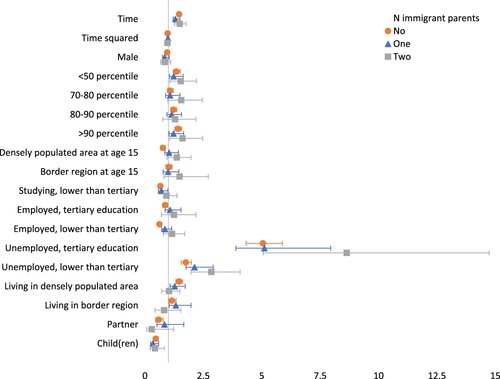

As shown above, we found the highest chance to emigrate among individuals with two immigrant parents. Important to note, however, is that this group makes up only 13 per cent within the Western European second generation in our study population. Moreover, the group with two immigrant parents turns out to be quite diverse: around 65 per cent had parents born in two different countries, and half of the individuals with two immigrant parents had one parent from a non-European country. This forms a clear difference with more often studied non-Western groups within the second generation (e.g. the Turkish second generation), of whom the vast majority has two immigrant parents, typically from the same country. As previous studies on the second generation for that reason seldom differentiated by the number of immigrant parents, in our case doing so seems a relevant endeavour. As a robustness check, we therefore estimated the complete model separately for individuals with no, one and two immigrant parents. The results are presented (for the odds ratios, see in the Appendix).

Figure 3. Odds ratios of event history models for emigration over early adulthood, by number of immigrant parents.

First and foremost, the figure shows that the confidence intervals are quite broad for the group with two immigrant parents, indicating large variation within this group. Possibly, part of the variation stems from differences between individuals with two parents from (Western) European countries, versus those who also have a parent from outside Europe. In our study population, the number of individuals with two immigrant parents is too low to distinguish more homogenous subgroups, for instance based on specific combinations of origin countries of the parents. However, studying this group in greater detail seems a relevant endeavour for future research.

When comparing the results by the number of immigrant parents, three findings stand out. First, growing up in households with the highest income levels seems a more important predictor of the migration potential of individuals with two immigrant parents, although the broad confidence intervals indicate that the effect is less robust for this group. Second, individuals without immigrant parents emigrate more often while enrolled in higher education while individuals with two immigrant parents more often emigrate from a situation of unemployment. These findings suggest different types of mobilities: that is, emigration for the purpose of study – possibly a short-term ERASMUS experience, versus emigration in search of work, which may be more permanent. One way for future research to shed more light on these patterns is to investigate the likelihood of a return to the Netherlands, and the length of stay abroad. Finally, in the previous section, we saw how moving to the most densely populated areas since turning 15 years old was found to increase the likelihood of emigration. In the separate models, however, this pattern only emerges among individuals without immigrant parents. One could explain this difference as the second generation more often grows up in the most densely populated areas, and thus often already lives there as they reach adulthood. Yet perhaps more importantly, the finding illustrates that something about these internal moves seems to contribute to the mobility capital of individuals without a migration background. As increasing intra-EU mobility is one of the main aims of the EU project, investigating the underlying mechanisms behind this result provides a relevant direction for further research.

5. Discussion

Due to the right to freedom of movement, EU citizens have a high degree of control over their own cross-border movements without being hampered by legal obstacles, as is the case for third country nationals. Still, the right to freedom of movement is exercised far less by EU citizens than one could expect given the low legal barriers to migrate to another EU member state. Clearly, the decision to emigrate requires more than openness of borders alone. In this study, we investigated to what extent a person’s own migration potential is influenced by the family’s history of migration. We argued that having immigrant parents may increase the chance of emigration due the intergenerational transmission of ‘mobility capital’, i.e. skills, values and preferences that facilitate migration. The analyses indeed show that the second generation has a higher chance to emigrate from the Netherlands than individuals without a migration background, and that this difference remains when taking socio-economic indicators, current individual demographics, and household characteristics at age 15 into account. These findings support the expectation that ‘mobility capital’, like other forms of capital (e.g. social, human), is transmitted from parents to their children. As such, the study is among the first to identify having a second-generation migration background as an important predictor of international migration. The findings stress the need for future studies to acknowledge and pay more empirical attention to this mobility capital, which goes over and beyond socio-economic characteristics of the person. The study further joins the argument for more reflexivity in migration studies, opposing a harsh demarcation between ‘migrants’ and ‘non-migrants’ (e.g. Dahinden Citation2016). We acknowledge that mobility capital is not confined to those with previous migration experience, but can be used to describe the potential to emigrate versus to stay for all individuals within society.

While the literature has often focused on an individual’s economic position and social ties to explain the likelihood of emigration, the findings further point at the importance of geographical location. To start with, chances to emigrate appear higher among individuals living in the border regions of the Netherlands. As main areas for sending and receiving EU migrants, these regions may play an important role in the process of European integration. What is more, while the migration literature recognises that international migration is often preceded by internal moves to the big cities in developing countries, we observed a similar mobility pattern from rural, to urban, to international migration among Dutch individuals emigrating from the Netherlands. Thus, while emigration decisions in Western Europe take shape under different circumstances than those in African or Asian origin countries, similar geographical patterns can be observed in the sense that big cities appear important steppingstones for international migration.

Despite the relevant insights gained with this study, several important pathways to advance our research can be pointed at. First, although the Dutch population registers provide a rich and detailed data source describing a large number of people over a longer period of time, the nature of the data has restricted our analyses to indicators and outcomes that are formally registered. In turn, we were not able to test expectations regarding migration motives, nor to include explanatory factors like social networks, norms and values, language skills or cultural identity in the models. To gain further insight into the mechanisms behind what we describe as the ‘intergenerational transmission of mobility capital’, different types of data and methods are needed to complement and extent our findings.

Second, the study shows that only a small share of the Western European second generation in the Netherlands had two immigrant parents from the same Western European country. This composition is notable, as research in Western European societies has mainly focused on the children of non-Western immigrants who seldom grow up in bi-national families. Although prior research has indeed indicated that intercultural relationships are not uncommon among mobile EU citizens (e.g. Haandrikman Citation2014), this composition may also signal a certain selection effect. That is, driven by social ties and culture preferences, couples consisting of two mobile EU citizens with the same Western European background may be more likely to move back to their origin country prior to having children, or before the child reaches school age (see Dustmann Citation2003). In fact, such mechanisms may imply that a substantial share of the second generation experiences their first international move already prior to reaching adult ages. While beyond the scope of the present study, investigating the impact of childhood migration on international migration behaviour later in life forms another interesting direction for future research.

Finally, it would be worthwhile to replicate the study and understand whether similar patterns and explanations are found for other origin groups and countries. A few interesting examples for future studies can be pointed at. To start with, while Western European countries traditionally have been the main countries of origin of European immigrants in the Netherlands, migration from Eastern European countries to Western Europe has rapidly increased after these countries joined the EU in 2004 and 2007. Investigating the migration behaviour of the second generation of Eastern European descent presents a relevant pathway for future studies as this group reaches adulthood in the years to come. Furthermore, and while we have had clear reasons to focus on the children of Western European migrants for the purpose of this study, empirical literature on the emigration behaviour of the second generation with a non-Western background is scarce as well. Addressing this gap in the literature is desirable and will contribute to a better understanding of the impact of having immigrant parents on migration decisions, as well as population dynamics in general. At the same time, in comparing the emigration rates of the non-Western second generation and their peers without a migration background, future studies should be careful to take differences related to citizenship rights into account between these groups and individuals without a migration background. What is more, as the children of non-Western immigrants more often experience a marginalised position in society, prior research focusing on the non-Western second generation has often explained their migration aspirations to the country of origin of the parents as ‘reactive transnationalism’. In a similar vein, the migration behaviour of this group may be fuelled by experiences of discrimination and lack of opportunities in the place of residence, resulting in different migration dynamics than the ones studied in this study.

While migration is often a subject of concern in Western European countries, and framed in terms of integration and social cohesion, mobility is typically perceived rather positively and is even promoted (Faist Citation2013; Glick Schiller and Salazar Citation2013). Underlying the promotion of youth mobility, EU policies seem to assume increased mobility over the life course (Bertoncini Citation2008), which would contribute to ‘the grand vision of a united European space characterised by unrestricted flows of goods, people, capital and services’ (Jensen and Richardson Citation2004). Moves during early adulthood are often part of exploring future social and professional opportunities, and hence may considerably affect a person’s future life trajectory (Frändberg Citation2014). As this study focused on the first emigration since turning 18, it remains to be seen to what extent mobility over early adulthood leads to transnational lives. Furthermore, while previous literature has demonstrated an impact of migration on the timing of relationship and family formation of non-Western immigrants (e.g. Andersson Citation2004), we know much less about the consequences of EU mobility on such demographic behaviour. Findings of this study stress the importance of investigating such additional ways in which EU mobility may affect the population dynamics in European societies.

To conclude, this study has importantly and innovatively illustrated that EU mobility of parents has an impact on the likelihood that their children will become mobile. As the European second generation is expected to grow and make up a significant share within Western European populations over the years to come, these findings regarding their mobility can be expected to have a long-term impact, not just for the individual life, but also at the population level, and will have important implications for projections on future migration.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Statistics Netherlands for providing the data and for the collaboration.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study have been prepared for analysis at Statistics Netherlands. The data are not publicly available, as they contain information that could compromise the privacy of the individuals in the research population.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In case immigrant parents are born in different Western European countries, a person is grouped by the country of origin of the mother.

References

- Allison, P. D. 2014. “Event History and Survival Analysis.” In Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences; series/number 07-46. 2nd ed. SAGE. http://srmo.sagepub.com/view/event-history-analysis-2e/SAGE.xml.

- Andersson, G. 2004. “Childbearing After Migration: Fertility Patterns of Foreign-born Women in Sweden.” International Migration Review 38 (2): 747–774. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7379.2004.tb00216.x.

- Bakker, B. F. M., J. Van Rooijen, and L. Van Toor. 2014. “The System of Social Statistical Datasets of Statistics Netherlands: An Integral Approach to the Production of Register-Based Social Statistics.” Statistical Journal of the IAOS 30 (4): 411–424. doi:10.3233/SJI-140803.

- Beck, U. 2007. “Beyond Class and Nation: Reframing Social Inequalities in a Globalizing world1.” The British Journal of Sociology 58 (4): 679–705. doi:10.1111/j.1468-4446.2007.00171.x.

- Bernard, A., and S. Vidal. 2020. “Does Moving in Childhood and Adolescence Affect Residential Mobility in Adulthood? An Analysis of Long-Term Individual Residential Trajectories in 11 European Countries.” Population, Space and Place 26 (1): e2286. doi:10.1002/psp.2286.

- Bertoncini, Y. 2008. Encourage Young People’s Mobility in Europe: Strategic Orientations for France and the European Union. Paris.

- Bettin, G., E. Cela, and T. Fokkema. 2018. “Return Intentions Over the Life Course: Evidence on the Effects of Life Events from a Longitudinal Sample of First- and Second-generation Turkish Migrants in Germany.” Demographic Research 39 (38): 1009–1038. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2018.39.38.

- Bijwaard, G. E., and J. Wahba. 2014. “Do High-income or Low-income Immigrants Leave Faster?” Journal of Development Economics 108: 54–68. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2014.01.006.

- Brandle, V. K. 2020. “Reality Bites: EU mobiles’ Experiences of Citizenship on the Local Level.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46: 2800–2817. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1524750.

- Cairns, D. 2014. ““I Wouldn't Stay Here”: Economic Crisis and Youth Mobility in Ireland.” International Migration 52 (3): 236–249. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2012.00776.x.

- Cairns, D., K. Growiec, and J. Smyth. 2013. “Leaving Northern Ireland: Youth Mobility Field, Habitus and Recession among Undergraduates in Belfast.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 34 (4): 544–562. doi:10.1080/01425692.2012.723869.

- Cairns, D., and J. Smyth. 2011. “I Wouldn't Mind Moving Actually: Exploring Student Mobility in Northern Ireland.” International Migration 49 (2): 135–161. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2009.00533.x.

- Carling, J., and K. Schewel. 2018. “Revisiting Aspiration and Ability in International Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (6): 945–963. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1384146.

- Çelik, G., and T. Notten. 2014. “The Exodus from the Netherlands or Brain Circulation: Push and Pull Factors of Remigration among Highly Educated Turkish Dutch.” European Review 22 (3): 403–413. doi:10.1017/S1062798714000246.

- Clark, W. A., and W. Lisowski. 2018. “Examining the Life Course Sequence of Intending to Move and Moving.” Population, Space and Place 24 (3): e2100. doi:10.1002/psp.2100.

- Conradson, D., and A. Latham. 2005. “Friendship, Networks and Transnationality in a World City: Antipodean Transmigrants in London.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 31 (2): 287–305. doi:10.1080/1369183042000339936.

- Crul, M., and J. Doomernik. 2003. “The Turkish and Moroccan Second Generation in the Netherlands: Divergent Trends Between and Polarization Within the Two Groups.” International Migration Review 37 (4): 1039–1064. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7379.2003.tb00169.x.

- Dahinden, J. 2016. “A Plea for the ‘De-Migranticization' of Research on Migration and Integration.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 39 (13): 2207–2225.

- De Haas, H. 2010. “Migration and Development: A Theoretical Perspective.” International Migration Review 44 (1): 227–264. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7379.2009.00804.x.

- De Jong, P. W. 2021. “Patterns and Drivers of Emigration of the Turkish Second Generation in the Netherlands.” European Journal of Population, 1–22. doi:10.1007/s10680-021-09598-w.

- De Jong, P. W., G. G. Wachter, and D. Dieleman. 2020. Emigratie van de tweede generatie.

- Deléchat, C. 2001. “International Migration Dynamics: The Role of Experience and Social Networks.” Labour 15 (3): 457–486. doi:10.1111/1467-9914.00173.

- Dustmann, C. 2003. “Children and Return Migration.” Journal of Population Economics 16 (4): 815–830. doi:10.1007/s00148-003-0161-2.

- Faist, T. 2013. “The Mobility Turn: A New Paradigm for the Social Sciences?” Ethnic and Racial Studies 36 (11): 1637–1646. doi:10.1080/01419870.2013.812229.

- Fokkema, C. M. 2011. “Return” Migration Intentions among Second-Generation Turks in Europe: The Effect of Integration and Transnationalism in a Cross-national Perspective.” Journal of Mediterranean Studies 20 (2): 365–388.

- Frändberg, L. 2014. “Temporary Transnational Youth Migration and its Mobility Links.” Mobilities 9 (1): 146–164. doi:10.1080/17450101.2013.769719.

- Gielis, R. 2009. “Borders Make the Difference: Migrant Transnationalism as a Border Experience.” Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie 100 (5): 598–609. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9663.2009.00572.x.

- Glick Schiller, N., and N. B. Salazar. 2013. “Regimes of Mobility Across the Globe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39 (2): 183–200. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2013.723253.

- Graef, P., and J. Mulder. 2003. Wonen over de grens. Een Onderzoek naar Woonmigratie van Nederlanders naar Duitsland. Enschede.

- Groenewold, G., and H. A. G. De Valk. 2017. “Acculturation Style, Transnational Behaviour, and Return-Migration Intentions of the Turkish Second Generation: Exploring Linkages.” Demographic Research 37: 1707–1734. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2017.37.53.

- Gundel, S., and H. Peters. 2008. “What Determines the Duration of Stay of Immigrants in Germany?” International Journal of Social Economics 35 (11): 769–782. doi:10.1108/03068290810905414.

- Haandrikman, K. 2014. “Binational Marriages in Sweden: Is There an EU Effect?” Population, Space and Place 20 (2): 177–199. doi:10.1002/psp.1770.

- Hammarstedt, M. 2009. “Intergenerational Mobility and the Earnings Position of First-, Second-, and Third-generation Immigrants.” Kyklos 62 (2): 275–292. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6435.2009.00436.x.

- Hermansen, A. S. 2016. “Moving Up or Falling Behind? Intergenerational Socioeconomic Transmission among Children of Immigrants in Norway.” European Sociological Review 32 (5): 675–689. doi:10.1093/esr/jcw024.

- Hoon, M. d., M. Vink, and H. Schmeets. 2020. “A Ticket to Mobility? Naturalisation and Subsequent Migration of Refugees After Obtaining Asylum in the Netherlands.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (7): 1185–1204. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1629894.

- Huinink, J., S. Vidal, and S. Kley. 2014. “Individuals’ Openness to Migrate and Job Mobility.” Social Science Research 44: 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.10.006.

- Jensen, O. B., and T. Richardson. 2004. Making European Space: Mobility, Power and Territorial Identity. http://site.ebrary.com/id/10098718.

- King, R., and A. Christou. 2014. “Second-Generation “Return” to Greece: New Dynamics of Transnationalism and Integration.” International Migration 52 (6): 85–99. doi:10.1111/imig.12149.

- Koelet, S., C. Van Mol, and H. A. De Valk. 2017. “Social Embeddedness in a Harmonized Europe: The Social Networks of European Migrants with a Native Partner in Belgium and the Netherlands.” Global Networks 17 (3): 441–459. doi:10.1111/glob.12123.

- Kriesi, H., E. Grande, R. Lachat, M. Dolezal, S. Bornschier, and T. Frey. 2008. West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Labussière, M., and M. Vink. 2020. “The Intergenerational Impact of Naturalisation Reforms: The Citizenship Status of Children of Immigrants in the Netherlands, 1995–2016.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 1–22. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1724533.

- Laurijssen, I., and I. Glorieux. 2015. “Early Career Occupational Mobility of Turkish and Moroccan Second-Generation Migrants in Flanders, Belgium.” Journal of Youth Studies 18 (1): 101–117. doi:10.1080/13676261.2014.933194.

- Lee, E. S. 1966. “A Theory of Migration.” Demography 3 (1): 47–57. doi:10.2307/2060063.

- Levitt, P. 2009. “Roots and Routes: Understanding the Lives of the Second Generation Transnationally.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35 (7): 1225–1242. doi:10.1080/13691830903006309.

- Lundborg, P., M. Nordin, and D. O. Rooth. 2018. “The Intergenerational Transmission of Human Capital: The Role of Skills and Health.” Journal of Population Economics 31 (4): 1035–1065. doi:10.1007/s00148-018-0702-3.

- Moret, J. 2020. “Mobility Capital: Somali Migrants’ Trajectories of (Im)Mobilities and the Negotiation of Social Inequalities Across Borders.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 116: 235–242. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.12.002.

- Moriarty, E., J. Wickham, S. Daly, and A. Bobek. 2015. “Graduate Emigration from Ireland: Navigating New Pathways in Familiar Places.” Irish Journal of Sociology 23 (2): 71–92. doi:10.7227/IJS.23.2.6.

- Murphy-Lejeune, E. 2002. Student Mobility and Narrative in Europe: The New Strangers. London: Routledge.

- Myers, S. M. 1999. “Residential Mobility as a Way of Life: Evidence of Intergenerational Similarities.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 61: 871–880. doi:10.2307/354009.

- Pelliccia, A. 2017. “Ancestral Return Migration and Second-generation Greeks in Italy.” Journal of Modern Greek Studies 35 (1): 129–154. doi:10.1353/mgs.2017.0006.

- Schewel, K. 2020. “Understanding Immobility: Moving Beyond the Mobility Bias in Migration Studies.” International Migration Review 54: 328–355. doi:10.1177/0197918319831952.

- Van Houtum, H., and R. Gielis. 2006. “Elastic Migration: The Case of Dutch Short-distance Transmigrants in Belgian and German Borderlands.” Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie 97 (2): 195–202. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9663.2006.00512.x.

- Van Mol, C. 2019. “Intra-European Student Mobility and the Different Meanings of ‘Europe’.” Acta Sociologica, 0001699319833135.

- Van Mol, C., and H. A. G. De Valk. 2018. “European Movers’ Language use Patterns at Home: A Case-Study of European Bi-national Families in the Netherlands.” European Societies 20 (4): 665–689. doi:10.1080/14616696.2018.1437200.

- Van Mol, C., H. A. G. De Valk, and L. Van Wissen. 2015. “Falling in Love with(in) Europe: European Bi-National Love Relationships, European Identification and Transnational Solidarity.” European Union Politics 16 (4): 469–489. doi:10.1177/1465116515588621.

- van Wissen, L. J. G., and L. Heering. 2014. “Trends and Patterns in Euro-marriages in the Netherlands.” Population, Space and Place 20 (2): 126–138. doi:10.1002/psp.1769.

- Venhorst, V., J. Van Dijk, and L. Van Wissen. 2010. “Do the Best Graduates Leave the Peripheral Areas of the Netherlands?” Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie 101 (5): 521–537. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9663.2010.00629.x.

- Weiss, H. E. 2012. “The Intergenerational Transmission of Social Capital: A Developmental Approach to Adolescent Social Capital Formation*.” Sociological Inquiry 82 (2): 212–235. doi:10.1111/j.1475-682X.2012.00414.x.

- White, A., and K. Goodwin. 2021. “Invisible Poles and their Integration into Polish Society: Changing Identities of UK Second-generation Migrants in the Brexit Era.” Social Identities 27 (3): 410–425. doi:10.1080/13504630.2020.1859361.

Appendix

Table A1. Descriptive statistics measured at time of emigration or censoring, by number of immigrant parents.

Table A2. Results from event history models for emigration over early adulthood, by number of immigrant parents.