ABSTRACT

Richard Alba has been at the forefront of renewing classical assimilation theory based on empirical data on post-1960s migrants in the US. He focused on the assimilation of migrant groups into the dominant non-Hispanic white majority group. This article − once again − rethinks assimilation theory. I argue that the new demographic reality in majority–minority cities in Europe and North America necessitates a new research direction, entailing the development of a novel theoretical framework and partially new research tools. Not only has the relative size of the majority group decreased, but shifting positions of power are also challenging us to rethink assimilation frameworks. I propose to look at present-day processes of integration and assimilation more as multi-directional. Everyone (including the former majority group) integrates into the ethnically and racially diverse urban context. I outline the contours of a new theoretical framework: Integration into Diversity (ID) Theory. This article focuses on how members of the former majority group integrate into the diverse city context. Based on their diversity attitudes and diversity practices, I analyse how their ID positions relate to socio-economic outcomes, the quality of inter-ethnic relations and feelings of belonging and safety.

1. Introduction

Richard Alba has been at the forefront of developing theoretical frameworks and concepts to analyze and understand assimilation processes for migrants that started to arrive in the 1960s and their American-born children, the second generation. Alba’s core contribution, together with Victor Nee, has been to revise and reformulate the classical assimilation theory (Citation2003). Central to their contribution is the understanding of how ethnic boundaries for migrants and their offspring become more and more blurred over time for the second and third generations. A key concept in Alba’s work is ‘the expanding mainstream’ (Citation2009). Irish Catholics, Russian Jews, and Catholic Italians all became part of this expanding mainstream over time. In his latest book, Alba argues that children born out of mixed unions between Asians and whites and Latinx and whites often identify as white and that they will be able to blur the colour line further and enter the mainstream too (Alba Citation2020).

The new assimilation theory by Alba and Nee (Citation2003) and segmented assimilation theory by Portes and others (Portes and Zhou Citation1993; Portes and Rumbaut Citation2001) have laid the foundation for an immense amount of research in the field of migration and ethnic studies that spans the globe. Portes and others (idem.) have outlined three different assimilation positions: classical assimilation, whereby people become similar to the Anglo-Saxon white group (now non-Hispanic whites) over time; downward assimilation into the inner-city ‘underclass’; and a third position in which groups resist Americanisation and build on their own ethnic capital and social cohesion. Alba and Nee (Citation2003) argue that in the long run, classical assimilation is still the main trend, also for groups in this third position. Most members of this latter group will first assimilate economically and their cultural adaptation will mostly follow in the second and third generations.

Alba’s empirical research involves comparative studies in different continents. His transatlantic comparison, made together with Nancy Foner, shows their impressive knowledge of a range of European countries and their specific migration histories (Alba and Foner Citation2015). Alba’s prominence in the field and large network in combination with his enchanting natural curiosity have enabled him to acquire a truly deep knowledge of these country contexts and their migrant groups. His empirical and theoretical work, which spans decades, has made an immense contribution to the fast-expanding field of migration and ethnic studies and has helped generations of researchers understand the complex societal processes related to migrants and their children.

In both the New Assimilation Theory and the Segmented Assimilation Theory the authors basically looked at two types of important indicators in relation to the assimilation process: people’s attitudes and people’s practices. People’s attitudes were assessed by looking, for example, at their resistance to Americanisation, whether or not they had embraced the values of the dominant majority group, or, in the case of one of the pathways of segmented assimilation, their adaptation to the norms and values of the urban underclass by, for example, adopting over an anti-school attitude. People’s social practices in relation to assimilation were measured by mapping how many of their friends belong to the majority group or whether they were in a union with someone from the majority group. For some ethnic groups, the level of openness to the dominant majority culture is related to educational or labour market gains, while for other ethnic groups, reliance on their group’s cultural norms and values secures educational success in the second generation.

Overall, looking at the mechanisms studied by Alba and others empirically, we could say that openness towards or rejection of the dominant culture’s norms and values are considered crucial elements in understanding different assimilation pathways. People’s social practices, like their circle of friends and partner choice, are also important because they have important consequences for their social and cultural capital. Alba and others consider contact with people from the majority group especially important as this enables newcomers to access information and to adopt the norms and values of the majority group and thus become part of mainstream society.

My ambition for this article is to see how we can, once again, renew New Assimilation Theory, some twenty years after it was formulated by Alba and Nee. One of the main reasons for doing so is the demographic developments in Europe’s and North America’s major cities in the new millennium that have turned these cities into majority-minority cities. This situation raises new questions about assimilation. In the US, a majority-minority context is described as a context in which the non-Hispanic white group is a numerical minority group among other numerical minorities. In continental Europe, a majority-minority context is described as a context in which people without a migration background form a numerical minority. Nowadays most continental European countries use the distinction ‘people with a migration background’ and ‘people without a migration background’. These are mutually exclusive categories. People without a migration background are people who are born in the survey country as are both their parents. The category ‘people without a migration background’ is not synonymous with an ethnic or racial group and also includes non-white people of the third generation and more. For this article I have, however, excluded those who identify as being of mixed race or from a migrant origin (third generation or more) from the analyses. I refer to the remaining group in this article as the (former) majority group.

Alba and Nee largely approached assimilation as a uni-directional relationship in which members of different migrant groups enter the mainstream by becoming more similar, both in cultural and socio-economic terms, to the dominant white majority group. I want to emphasise that this way of analyzing made perfect sense for the time period that they studied. The primarily uni-directional focus of the New Assimilation Theory largely fitted the demographic reality of the second part of the last century up until the 1990s. Because of the huge imbalance between the size of the dominant majority group versus the smaller newcomer groups and the imbalance in power, the pressure to adapt rested mainly on the new migrants and their children. Both in more equal social settings, such as children in a school class, and in settings characterised by clear power relationships, such as an employer-employee setting, the power to decide about the rules of engagement was clearly in the hands of the majority group. Alba and others therefore mainly focused on the potential assimilation pathways of migrants and their children, taking into consideration what the different ethnic groups brought with them in terms of useful cultural and social capital (Alba and Nee Citation2003; See also Portes and Zhou Citation1993; Portes and Rumbaut Citation2001).

The theoretical shift I am proposing in this article is a gradual shift from theories like the New Assimilation Theory and Segmented Assimilation Theory towards a new theoretical framework that, over time, will be a better fit with the new reality of majority-minority cities, soon to be followed by majority-minority states, and even majority-minority countries in the future. I argue that contemporary assimilation theories have been very useful for studying contexts in which there is a clear majority group and in which members of this majority group hold most of the power positions. In many present-day urban realities, however, the former majority group is no longer a numerical majority. Their numbers are declining fast and in many neighbourhoods, they do not even form the largest numerical minority group anymore. At the same time, partly because of processes of globalisation and partly because of social mobility among the second and third generation, positions of power are no longer only in the hands of the former majority group. How quickly this new societal situation becomes a reality varies from country to country and from city to city. Societal processes of assimilation, as we knew them, will slowly be replaced by new societal processes, for which we must find new concepts and new theoretical frameworks.

The core idea for the framework that I am proposing is to look at this societal process in majority-minority contexts as a bi-directional or multi-directional process in which members of the former majority group also need to make an effort to become part of the highly diverse context in which they live, work, and go to school. And secondly, I propose to include in the new framework the assertion that positions of power are not always in the hands of the former majority group. As Alba has also described in more recent research, more and more people from non-white groups are entering into leadership positions. This development has placed people from the former majority group on a more equal footing with people from other ethnic and racial groups; in fact, they may occupy subordinate positions when people from other ethnic and racial groups are their supervisors or employers. How do people from the former majority group react to this latter scenario?

The changing demographic context of majority-minority cities also requires us to rethink the concept of the mainstream. The implicit assumption of the concept of ‘the mainstream’ is that all members of the (former) majority group are already part of this mainstream. It seems to be somehow overlooked that the context, when we assume that the mainstream is changing, might be posing many new challenges for this group in terms of participating and belonging to this expanded mainstream. The concept of ‘the mainstream’ also supposes both a more symbolic (culture, language) and physical (ethnic neighbourhoods or ethnic enclaves) context outside of ‘the mainstream’, where other norms, values and rules of engagement are valid. How people belonging to the (former) majority group navigate spaces and contexts that are not considered ‘mainstream’ is a largely under-researched aspect. In contexts and spaces where members of the former majority group form a numerical minority group, their position might feel less secure and the dominance of their rules of engagement less evident. If they express resistance towards the diversity around them, this might lead to conflict and could very well diminish their feelings of safety and belonging.

Thinking through the consequences of these new societal processes means developing an alternative framework that builds on some of the key assumptions of new and segmented assimilation theory. In this new reality we need, once again, to look at people’s attitudes and practices, as assimilation theorists have done in the past. But this time, we have not only looked at the attitudes and practices of people belonging to migrant or minority groups, but also at those of the people belonging to the former majority group. We should also study what the consequences of their attitudes and practices are while living in a majority-minority context. How does it impact people’s position in society if they reject the migration-related diversity of today’s society and what are the consequences if they self-segregate? These are empirical questions that have not yet been asked by previous assimilation theorists. We can also ask what happens when members of the former majority group find themselves in a subordinate position to people with a migration background. Are they able to adapt to a reversed power relationship? If not, what are the consequences for their own feelings of well-being and, also interesting, for their socio-economic position?

Asking these new questions has prompted us to think of a new theoretical framework that would be able to capture these situations and analyze these positions and their potential impact. The framework we developed is the Integration into Diversity (ID) Theory (See also Crul and Lelie Citation2023). I propose that rather than thinking of a mainstream context and contexts outside of that mainstream, we should take the ethnically and racially diverse city and neighbourhood as the starting point when we research the context in which people live, interact, and try to belong (Crul Citation2016). Based on their attitudes and practices we can identify whether people are more or less integrated into the diverse society in which they live and whether or not the different levels of integration have consequences for their well-being, feeling of safety, or socio-economic situation. This is true for both people who belong to the former majority group and those who do not belong to this group. In this article, I will concentrate on the former majority group because they are the group that is mostly overlooked in assimilation research. In our framework the (previous) majority group is not automatically considered the norm group and it is not assumed that individual members of this group can set the rules of engagement; rather, this is empirically tested. This is especially relevant regarding members of the former majority group who are in subordinate positions and lack the individual power to dominate spaces or set rules of engagements. However, it is also relevant in settings with more equal power relations, such as semi-public spaces in neighbourhoods with a high level of diversity. By studying different Integration into Diversity (ID) positions, we can see how they relate to people’s socio-economic and socio-cultural outcomes.

2. Renewing assimilation theory

The need to renew assimilation theory is driven by the new reality of the majority-minority context characterised by ethnic and racial diversity. I assume that settings with less ethnic and racial diversity will still largely be determined by classical and new assimilation processes due to the dominance of the majority group. The new framework we propose is mostly applicable in majority-minority contexts in mostly urban settings. This is the context in which, to our understanding, all groups need to ‘integrate into diversity’ to be able to participate successfully and achieve a sense of well-being and belonging.

This means that from the onset the focus of our research will be different than that of assimilation theorists. The aim is to assess how skilful people are in navigating an ethnically and racially diverse context. The main difference is that, as a result, we will also study the integration of the former majority group into this diverse context. We will, for instance, assess whether their social circle reflects the ethnic and racial diversity around them, and if not, whether this limits their access to different forms of social and cultural capital. We can then investigate whether those who are better ‘integrated into diversity’ also show better socio-economic outcomes than those who are less well-adapted. Do they also have a greater sense of belonging and well-being than, for instance, those who self-segregate in their own ethnic group?

With these questions, we will study the societal process of integration as a multi-directional process in which all groups need to make an effort to belong and become successful. It also forces us to look at the process of integration as a more general sociological process not specifically aimed at only migrants, but at all inhabitants, whether or not they have a migration background. This is maybe best explained by zooming in on a particular position, that of a subgroup of people who see their own cultural norms and values as superior and who largely avoid having any personal contact with members of other ethnic and racial groups. We find people from this subgroup among both the former majority group and among people who do not belong to this group. Both can be characterised by a lack of acceptance and flexibility in responding to an ethnically and racially diverse context. Both think that the close proximity of people with other cultural norms and values than their own threatens their way of living. The similarities between the members of this subgroup of people who prefer to ‘stick to their own’ show that this position has little to do with whether or not one has a migration background, or, conversely, is a member of the former majority group, but hints at broader sociological and psychological processes.

If we pursue this new avenue of research, we also need to revise the tools that assimilation researchers developed to assess contact, belonging and identity. In assimilation theory, a great many indicators have been developed to establish assimilation outcomes for migrant groups only, such as command of the national language, the number of non-Hispanic white friends, having a non-Hispanic white partner or identifying with the national identity. We can, however, adapt these indicators quite easily to include people from the former majority group. Let me give an example to illustrate the new pathway I want to explore. In assimilation theory, an indicator of successful assimilation is having many friends that belong to the non-Hispanic white group versus having only or mainly friends belonging to one’s own ethnic group. To analyse how members of the former majority group are integrated into diversity, I propose to look at the share of interethnic friendships versus the share of friends belonging to the former majority group. In more and more ethnically and racially diverse contexts, the former majority group is becoming an ever-smaller numerical group. If these people primarily interact with people belonging to the former majority group, their potential pool to form social circles is becoming smaller and smaller. The consequences of this new situation have hardly been studied. It could, for instance, mean that their opportunities to find a job are reduced because of their limited social network. Furthermore, self-segregation may also have an impact on their ability to successfully interact with colleagues, both employees or supervisors, from other ethnic and racial groups, thus affecting their productivity and their ability to fit into diverse teams. These are new research questions that we should investigate empirically. In the next paragraph, I will do this by showing different integration into diversity (ID) positions that we distinguished using the data from the Becoming a Minority (BaM) project.

I want to emphasise that my attempt to think through societal processes in diverse city contexts is not a plea to replace the New Assimilation Theory altogether. New assimilation processes as described by Alba and Nee are also found in the present-day demographic reality of majority-minority cities. My argument is that the proposed new theoretical framework will become more relevant over time as societies are becoming more ethnically and racially diverse and the former majority group is becoming smaller and less powerful. This can also mean that even in the distant future there will still be certain subfields or physical spaces, also within majority-minority cities, where new assimilation processes are dominant. For example, in order to find a job and get ahead in areas where the former majority group (still) holds most of the positions of power, it will still be important for newly arrived migrants to build a social network with people from this most powerful group and to understand their values and ways of thinking. But as society becomes more and more diverse, also in the higher echelons, I predict that being integrated into diversity in the form of building a diverse social network and understanding how to act in diverse settings will become more important. Or, to frame it more carefully, it will be an empirical question as to which societal context and at which level of ethnic and racial diversity individuals’ Integration into Diversity positions have more relevance for their social mobility and sense of belonging than new assimilation indicators that measure adaptation to the former majority group.

2.1. Integration into diversity theory

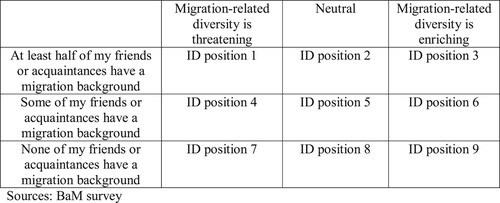

In this paragraph I will present the proposed new Integration into Diversity (ID) framework in more detail. The major aim of the ID framework is to measure different ID positions and related socio-economic outcomes and levels of well-being. To be able to measure integration into diversity we have developed the ID matrix. Like new assimilation theory, I argue that we should look at both people’s attitudes and their social practices. For this reason, we distinguish ID positions in the ID matrix based on two axes: diversity attitudes and diversity practices (see ). On the one axis we look at people’s attitudes towards the increased diversity of their neighbourhood. Do they see this as enriching or as threatening for their own culture? On the other axis we look at people’s social practices. Do they participate in and connect to the ethnically and racially diverse context in which they live, study, work and raise their children? We measured this by asking about the ethnic composition of their group of friends and acquaintances.

Figure 1. Integration into Diversity Matrix, Diversity Attitudes and Diversity Practices.

Sources: BaM survey.

The goal of the ID matrix is to assess whether different positions in terms of attitudes and/or practices relate to differences in socio-economic positions (income, employment, being dependent on benefits etc.) and well-being (feelings of belonging, identity and safety). Similar to the authors of assimilation theory, we will examine how attitudes and behaviours are related to different societal outcomes. This will enable us to build a hypothesis to test underlying mechanisms of integration into diversity for different subgroups. One hypothesis could, for instance, be that people belonging to the former majority group living in an ethnically and racially diverse context who see migration-related diversity as a threat and self-segregate will present more negative outcomes regarding their socio-economic position and well-being.

In line with classic and new assimilation theories, we acknowledge that there may be a contradiction between people’s attitudes and their practices. Some people have positive, or even very positive attitudes towards ethnic diversity, but when it comes to their own social circle, they almost only have meaningful contact with people from their own ethnic or racial background and, in effect, live a self-segregated life (ID Position 9). You could say that their practices do not align with their attitudes. This results in contrasting ID positions in the matrix, with some positions showing more integration into diversity and others less. ID position 3 can be labelled as the position of the people who are most integrated into diversity, while ID position 7 can be labelled as the position occupied by those who are least integrated into diversity.

The Integration into Diversity Matrix is a first step towards building a theoretical framework. I want to emphasise that it is not my intention, nor is it yet possible, to flesh out a completely new theoretical framework on par with New Assimilation Theory. More empirical research is required to make this possible. My intention here is merely to draw the potential contours of such a new theoretical framework. I will demonstrate the importance and relevance of this new approach, using BaM project data. One ambition for the future is to map the relative size of different integration into diversity positions in highly diverse neighbourhoods and cities, both for the former majority group and for other ethnic and racial groups living in these same neighbourhoods and cities. This would provide an important new indicator to explain the potential for either conflict or social cohesion within these contexts. This indicator could also be used to understand social mobility patterns in a city, if we take into consideration that positions of power are occupied by people from the former majority group as well as people who do not belong to the former majority group. However, my ambitions for this article are much more modest.

3. Integration into diversity matrix: different ID positions for people without a migration background

It is when new theoretical frameworks are tested empirically that they prove their worth. I will do this, using empirical findings from my last international comparative project: the Becoming a Minority (BaM) project. BaM looks at people without a migration background living in majority-minority neighbourhoods in major European cities. The findings I present therefore can only be related to majority-minority contexts. The dynamics in less ethnically and racially diverse contexts may be different.

The data for the BaM project were gathered in six European cities: Amsterdam, Antwerp, Hamburg, Malmö, Rotterdam and Vienna. We collected data in all of the majority-minority neighbourhoods in these cities. In these neighbourhoods we drew a sample of people between the age of 25 and 45 who were born in the country and whose both parents were also born there. We chose this age cohort because people often make important decisions about where they want to live in this particular part of their life course. They also often find a partner during this period and some already have a family and have to make choices on where to raise their children and which schools their children will attend. This group is particularly interesting due to the decisions they make in relation to the diverse context in which they live. But at the same time, choosing this age cohort means that we do not claim that their responses are representative of all people without a migration background in these majority-minority neighbourhoods.

For the analyses for this article, I restricted the sample further by excluding people who self-identified as being of mixed origin or descendants of older migration cohorts (third generation and onwards). This created a sample of people without a migration background who do not identify as being of migrant origin in older generations or as being mixed. We call this group the former majority group in the analysis.

In most cities, we used population register data to sample this group. If this was not possible, we used the available register data and screening based on name recognition (onomastic sampling). We then screened people to determine whether they belonged to our target group. We approached our respondents by sending them a letter, asking them to fill in the online questionnaire. If they did not respond, we sent them a reminder and a paper questionnaire. After assessing that males from a lower-class background were still underrepresented, we approached people in lower-class neighbourhoods to ask them for face-to-face interviews (for more extensive details of the sampling method, see Crul et al. Citation2023).

In total, we interviewed about 3000 people in majority-minority neighbourhoods in six European cities. After excluding respondents who identified as having mixed backgrounds and people belonging to the third generation, the sample for analysis contained 2720 respondents. For more detailed analyses, see the BaM Special Issue of JEMS (Crul, Lelie, and Keskiner Citation2023). shows the percentage score for the different ID positions among the sample in all six cities. Here, I will only show the data for all six cities together. A comparison between cities is interesting, but beyond the scope of this article. I want to emphasise that differences in the percentages of the different ID positions between majority – minority neighbourhoods across the cities, but, also within the cities vary. All of the majority-minority neighbourhoods have their own characteristics. In several publications by members of the BaM team, we show that these differences, such as high-rise versus low-rise housing neighbourhoods, correlate with the size of the different ID groups in these particular contexts (See Crul, Lelie, and Keskiner Citation2023; Crul et al. Citation2023). One of the important contributions we hope to make with our research is analysing these differences to understand what fosters a positive practice of living together in highly diverse contexts. The ambition that I have for this article is, however, different. Here, I will use the full sample of people without a migration background living in majority-minority neighbourhoods in the six cities. This allows us to show ID positions among a sufficiently large sample (almost 3000 respondents) without the sample size in the separate ID position becoming too small for a more detailed analysis of ID sub-groups.

Table 1. Integration into the Diversity Matrix. ID Positions in six majority-minority cities.

The two most diametrically opposed groups in the ID matrix are the people in ID position 3 and 7. People in ID position 7 could be described as the group least integrated into diversity, while the people in ID position 3 can be described as the group most integrated into diversity. These groups turned out to be equal in size in our sample. We see that the group that sees diversity as an enrichment (60%) is much larger than the group that sees it as threatening (24%). The findings over all of the cities show a high percentage of people who self-segregate (37%), which is remarkable given that these are all people who live in majority – minority neighbourhoods. A third stated having no or hardly any friends or acquaintances with a migrant background. Only 17% has a group of friends and acquaintances that is representative of the neighbourhood composition.

4. What characterises the most opposite ID positions?

What does it mean in practice for the respondents to belong to one of the ID positions in the ID matrix? Due to lack of space, I will concentrate on the two ID positions that exhibit the most contrasting differences: people in ID position 3 and ID position 7. People in ID position 7 self-segregate within their own group while living in a majority-minority neighbourhood and they see migration-related diversity as a threat. The literature usually ascribes a number of characteristics to people in this group. They describe a feeling of becoming a minority (Craig and Richeson Citation2014), feelings of being a stranger in their neighbourhood, of unsafety, and economic ethnic competition (Hochschild Citation2016; Kaufmann Citation2014; Lamont Citation2002; Mepschen Citation2016; Schneider Citation2008), in addition to the feeling that they are the victim of reverse discrimination and unfair treatment, and are being neglected by society and politicians (Gest Citation2016; Haga Citation2000; Hochschild Citation2016; Klandermans, Linden, and Mayer Citation2005; Mepschen Citation2016; Stockemer Citation2016). These people usually position themselves on the political right (Arzheimer Citation2008; van der Brug and Fennema Citation2009; Dahlström and Esaiasson Citation2013; Rydgren Citation2008).

People in ID position 3, on the other hand, both live lives that are integrated into the diverse reality around them and see migration-related diversity as enriching. They could be considered the mirror group of the people in ID position 7, but, based on the literature, they can also be characterised by specific indicators. In the literature they are described as cosmo-multiculturalists (Haga Citation2000), diversity seekers (Blokland and van Eijk Citation2010) or their attitudes and behaviour are described as corner-shop cosmopolitanism (Wessendorf Citation2014). They are tolerant and open to different ethnic groups, which creates a sense of cosmopolitanism (Jiménez Citation2017, 91). The people in this group usually position themselves on the left politically (Crul and Lelie Citation2021; De Vries Citation2018; Rooduijn et al. Citation2017).

When we look at the BaM data analysis, the people in ID position 7 pretty much live up to how they are characterised in the literature. About a third (34%) reported feeling like a stranger in their neighbourhood. Within this group, 39% said that people in their neighbourhood cannot be trusted; 36% thought that people without a migration background are ‘discriminated against (reversed discrimination) often’ or ‘all the time’, and 40% said that it happens sometimes. Two-thirds thought that recent migrants are treated better by the government than people like themselves who were born in the country. About a third thought that they are systematically neglected in the country and slightly more than half thought that politicians are not interested in their problems. Slightly fewer than two-thirds position themselves on the political right or centre right. On almost all these indicators they differ from the people in ID position 3 at the highest significant level.

The people in ID position 3 also pretty much live up to the picture we have from the literature. An overwhelming 82% of the people in ID position 3 said that they feel at home in the neighbourhood. Only 11% felt like a stranger in the neighbourhood and 48% said that people can be trusted in the neighbourhood while only 9% disagreed with this statement. Among this group, 73% placed themselves on the political left and 68% disagreed with the statement that people like them are systematically neglected in this country. An astounding 82% said that they saw themselves as ‘a world citizen’ and about two-thirds disagreed with the statement that their national culture is superior to other cultures.

5. ID positions and the impact on socio-economic position and well-being

In line with traditional assimilation theories, we analysed whether there is a correlation between occupying one of these two opposite positions and the respondents’ socio-economic position in society. We looked at welfare dependency, unemployment and income, type of labour contract, house ownership and whether people have a supervisory position in the labour market. One could imagine that there is a relationship between self-segregation and negative attitudes towards diversity and socio-economic position. Do these people, for instance, have fewer chances in the labour market (because some of their potential employers could be people of migrant background) or are they less suitable for a supervisory position based on their negative opinions about diversity and self-segregation?

However, we did not find any significant differences between those in ID position 7 and those in ID position 3 when we looked at welfare dependency, unemployment, temporary or fixed contracts, income, being in a supervisory position or owning a house. Self-segregation has not (yet) impacted the socio-economic position of the people in ID position 7. We can conclude that being in ID Position 7 has not yet had a negative impact on being hired or being promoted to a supervisory position.

We were, however, able to examine whether people in ID position 7 reported negative interactions in the workplace more frequently by analysing the reported quality of the relationships with the people they work with on a daily basis. Especially interesting is the subgroup that works in lower-level jobs because they are most likely to encounter people who do not belong to the former majority group in their workplace. For instance, about a quarter (25%) of the respondents without a higher education diploma (no BA or MA diploma) in ID Position 7 reported that half or more of their colleagues have a migration background. When asked about the quality of relationships with their co-workers, people in ID position 7 (without a higher education diploma) reported having a negative relationship with their co-workers significantly more often than people in ID Position 3. A third of the lower educated group also reported being supervised by managers with a migration background (vertical power relations), putting them in an unequal position with people belonging to one of the migrant groups. The people in ID position 7 who reported having a supervisor/s with a migration background reported negative interactions in such environments significantly more often. As more and more workplaces are becoming culturally mixed and supervisors will also be of migrant origin more often, people in ID position 7 will find themselves in working situations that are problematic for them. Equally important, employers might start to find these employees problematic because of their involvement in conflicts in the workplace, or they might decide not to promote them because they do not consider them fit to lead a diverse team. Although our findings do not show this yet, the quality of relationships reported by this group indicates that this is a potential scenario, especially as the workplace will become more diverse in the future.

Another important domain for social well-being is the neighbourhood. Social relationships in the neighbourhood can be characterised by more equal power relations than we find in the workplace. Here we find a clear negative relationship between people in ID position 7 and their well-being. Respondents in ID position 7 who were living in majority-minority neighbourhoods reported feeling like a stranger in their own neighbourhood significantly (at the highest level) more often than respondents in ID position 3. They ‘feel like a minority’ significantly more often, and reported having more conflicts with and less trust in their fellow neighbourhood residents. Half (51%) of the respondents in ID position 7 reported that at least half of their neighbours have a migration background. Given their levels of self-segregation and statement that diversity is a threat, it is plausible to say that their housing situation could be described as uncomfortable, to say the least. This was further confirmed by how this group characterises interethnic interactions in the streets, shops and parks. Among the respondents in ID position 7, 52% characterised interethnic interactions in the streets as unpleasant. This percentage was 34% in the parks and 30% in shops. In a majority-minority neighbourhood where they will need to interact in an ethnically diverse context on a daily basis, this could be an emotionally draining experience. Thirty-eight percent of this group reported harassment in the street in the past year (as opposed to 22% in ID position 3). Their answers paint a picture of a group that experiences their neighbourhood as a hostile environment.

On the other side of the spectrum, the results for ID position 3 clearly show that being integrated into diversity offers considerable gains. These respondents said that they felt a strong sense of neighbourhood belonging, of feeling at home in the neighbourhood, and feeling safe there. They experienced less harassment, and mainly experienced pleasant interactions. Being integrated into diversity seemed to have a particularly positive impact on their socio-emotional well-being.

The overall results show that there is not −or not yet − a correlation between people’s ID positions and hard socio-economic outcomes such as income or occupying a supervisory position. This is probably due to the fact that power relations in the workspace have not yet changed dramatically. However, where they already have changed and our target group is working under people with a migration background, we can observe a negative relationship with well-being in the workplace. Furthermore, within semi-public spaces characterised by more equal social relations, those who are the least ‘integrated into diversity’ are already exhibiting significantly more unfavourable outcomes regarding their well-being.

6. Conclusion

In this article I have undertaken the task to − once again − rethink assimilation theory, building on decades of empirical work done by Richard Alba and his distinguished colleagues. I argue that the new demographic reality in majority-minority cities in Europe and North America necessitates a new research direction, entailing the development of a novel theoretical framework and partially new research tools. In his work, Alba has shown how the mainstream is expanding by including new groups. He argues that within this process people are becoming more similar to each other. I am not arguing that this process is not taking place. However, I would like to add that today’s society is characterised by a process of increasing ethnic and racial diversity, and by shifts in power positions whereby the dominance of the former majority group is no longer a given. These two processes will unfold in parallel to some extent while society is undergoing demographic change. To understand how this works out in practice, I have drawn the contours of a new theoretical framework: Integration into Diversity (ID) Theory. I developed an ID matrix to define the positions that people adopt within the Integration into Diversity framework. The ID theoretical framework will gain more relevance over time as societies become more ethnically and racially diverse and the former majority group becomes smaller in number and also less powerful. In formulating an ID theoretical framework, we identified nine potential ID positions. We found particularly large differences between the most contrasting ID positions. Peoples’ social well-being correlates with their social relationships in the workplace and in the majority-minority neighbourhood context they live in. Being strongly ‘integrated into diversity’ shows considerable gains in terms of feelings of belonging and safety. ‘Not being integrated into diversity’ is correlated with a number of negative social well-being indicators and we observed that adopting this attitude has a huge impact on people’s lives. Given the high incidences of conflict in semi-public spaces for this group, this ID position seems to lead to a feeling of being under permanent threat. Vertical power relations have not changed so dramatically, and members from the former majority group still mostly occupy the positions of power in the labour market. While ID Theory has already gained some traction to explain outcomes for social relationships in the workplace and at the neighbourhood level, it does not yet seem to influence socio-economic outcomes. I argue that this might be different in the future when more people with a migration background occupy positions of power and will employ and supervise people from the former majority group. The outcomes of the ID matrix can be used in future research to map and compare the diversity climate in neighbourhoods and in sectors like the labour market. This will also contribute to a better understanding of social mobility opportunities and feelings of belonging and identification with a neighbourhood or city of people with a migration background in different city and neighbourhood contexts. This could potentially help to contextualise integration outcomes for people with a migration background across different neighbourhood and city contexts.

In general, our empirical findings suggest a gradual acceptance of diversity as the new norm among members of the (former) majority group and increased social contact as their living and working environments become more ethnically and racially diverse. This outcome and optimistic outlook for the future are very much in line with the empirical findings based on Richard Alba’s New Assimilation Theory, which predicts social mobility for migrant groups and increased feelings of acceptance and belonging.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alba, R. 2009. Blurring the Color Line: The New Chance for a More Integrated America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Alba, R. 2020. The Great Demographic Illusion: Majority, Minority, and the Expanding American Mainstream. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Alba, R., and N. Foner. 2015. Strangers No More: Immigration and the Challenges of Integration in North America and Western Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Alba, R., and V. Nee. 2003. Remaking the American Mainstream: Assimilation and Contemporary Immigration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Arzheimer, K. 2008. “Protest, Neo-Liberalism or Anti-Immigrant Sentiment: What Motivates the Voters of the Extreme Right in Western Europe?” Zeitschrift für vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 2 (2): 173–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-008-0011-4.

- Blokland, T., and G. van Eijk. 2010. “Do People Who Like Diversity Practice Diversity in Neighbourhood Life? Neighbourhood Use and the Social Networks of ‘Diversity-Seekers’ in a Mixed Neighbourhood in the Netherlands.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36 (2): 313–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830903387436.

- Craig, M., and J. Richeson. 2014. “On the Precipice of a “Majority-Minority” America: Perceived Status Threat From the Racial Demographic Shift Affects White Americans’ Political Ideology.” Psychological Science 25 (6): 1189–1197. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614527113.

- Crul, M. 2016. “Super-diversity vs. Assimilation: How Complex Diversity in Majority–Minority Cities Challenges the Assumptions of Assimilation.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (1): 54–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2015.1061425.

- Crul, M., and F. Lelie. 2021. “Measuring the Impact of Diversity Attitudes and Practices of People Without Migration Background on Inclusion and Exclusion in Ethnically Diverse Contexts. Introducing the Diversity Attitudes and Practices Impact Scales.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 44 (13): 2350–2379. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2021.1906925.

- Crul, M., and F. Lelie. 2023. The New Minority. People Without a Migration Background in the Superdiverse City. Amsterdam: VU University Press.

- Crul, M., F. Lelie, and E. Keskiner. 2023. “Becoming a Minority.” Special Issue of the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (8).

- Crul, M., F. Lelie, E. Keskiner, L. Michon, and I. Waldring. 2023. “How do People Without Migration Background Experience and Impact Today’s Superdiverse Cities?” Introduction to the Special Issue of Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (8): 1937–1956. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2023.2182548.

- Dahlström, C., and P. Esaiasson. 2013. “The Immigration Issue and Anti-Immigrant Party Success in Sweden 1970-2006. A deviant case analysis.” Party Politics 19 (2): 343–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068811407600.

- De Vries, C. 2018. “The Cosmopolitan-Parochial Divide: Changing Patterns of Party and Electoral Competition in the Netherlands and Beyond.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (11): 1541–1565. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1339730.

- Gest, J. 2016. The New Minority. White Working-Class Politics in an age of Immigration and Inequality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Haga, G. 2000. White Nation. Fantasies of White Supremacy in a Multicultural Society. New York: Routledge.

- Hochschild, A. 2016. Strangers in their Own Land. Anger and Mourning on the American Right. New York: The New Press.

- Jiménez, T. 2017. The Other Side of Assimilation. How Immigrants are Changing American Live. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Kaufmann, E. 2014. “‘It's the Demography, Stupid’: Ethnic Change and Opposition to Immigration.” The Political Quarterly 85 (3): 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12090.

- Klandermans, B., A. Linden, and N. Mayer. 2005. “Le monde des militants d’extrême droite en Belgique, en France, en Allemagne, en Italie et aux Pays Bas.” Revue Internationale de Politique Comparée 12: 469–485.

- Lamont, M. 2002. The Dignity of Working Men. Morality and the Boundaries of Race, Class and Immigration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Mepschen, P. 2016. Everyday Autochthony. Difference, discontent, and the politics of home in Amsterdam. Amsterdam: UVA PhD Thesis.

- Portes, A., and R. Rumbaut. 2001. Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Portes, A., and M. Zhou. 1993. “The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and its Variants.” Annals 530: 74–96.

- Rooduijn, M., B. Burgoon, E. van Elsas, and H. van der Werfhorst. 2017. “Radical Distinction: Support for Radical Left and Radical Right Parties in Europe.” European Union Politics 18 (4): 536–559. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116517718091.

- Rydgren, R. 2008. “Immigration Sceptics, Xenophobes or Racists? Radical Right-Wing Voting in six West European Countries.” European Journal of Political Research 47 (6): 737–765. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2008.00784.x.

- Schneider, S. 2008. “Anti-Immigrant Attitudes in Europe: Outgroup Size and Perceived Ethnic Threat.” European Sociological Review 24 (1): 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcm034.

- Stockemer, D. 2016. “The Success of Radical Right-Wing Parties in Western European Regions – new Challenging Findings.” Journal of Contemporary European Studies 54 (4): 999–1016.

- van der Brug, W., and M. Fennema. 2009. “The Support Base of Radical Right Parties in the Enlarged European Union.” Journal of European Integration 31 (5): 589–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036330903145930.

- Wessendorf, S. 2014. Commonplace Diversity: Social Interactions in a Super-Diverse Context. Dordrecht: Springer.