?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

According to new assimilation theory, assimilation can entail not only the adoption, by immigrants, of the established population's cultural practices, but also the adoption, by the established population, of immigrants' cultural practices. However, empirical research on assimilation has either neglected adaptation on the part of the established population or identified only modest changes. We examine reactions to a massive and rapid inflow of immigrants, and specifically, those of Mexican-origin Californios around the time of the Gold Rush of 1849. Treating naming patterns as indicators of assimilation, we find that Mexican American children born in California after 1849 were significantly less likely to receive distinctively Hispanic first names. As a placebo test, we further show that a similar pattern does not obtain in areas (e.g. New Mexico) that did not experience a rapid inflow of new American settlers. The findings validate an important insight of new assimilation theory, as well as shed new light on contemporary research on demographic change.

1. Introduction

Classic assimilation theory characterises assimilation as a process that runs in one direction: from immigrants toward established populations (Gordon Citation1964). Alba and Nee's (Citation2003) new assimilation theory instead posits that assimilation involves changes among both immigrant and established populations that bring them closer together culturally.

Following Alba and Nee's important theoretical innovation, most empirical research on assimilation has continued to focus on changes among immigrant groups that bring them in line with established populations (Foner Citation2022). Jiménez (Citation2017) on the ‘other side of assimilation’ is an important exception, but even this work uncovers only limited change among the established population. Importantly, Jiménez's majority–Asian field site exists within a broader national context characterised by Whites', not Asians', numeric and cultural dominance.

What if the broader context were shifting more decisively toward immigrants, as many Americans, abetted by Census Bureau projections, believe is happening to the United States today (see Alba Citation2018, Citation2020; Alba, Rumbaut, and Marotz Citation2005)? Rapid, large-scale demographic turnover could lead established residents to adopt the cultural practices of immigrants, not simply to admire or admonish them at arms' length.

To illustrate such dynamics, we examine the reactions of an established population to a massive inflow of immigrants, and specifically those of Mexican origin Californios around the time of the California Gold Rush of 1849. In the decade following the discovery of gold, California witnessed a massive in-migration of settlers from the Eastern United States. We ask whether Californios adopted cultural practices, and specifically naming practices, associated with Anglo newcomers.

We use individual records from the 1860 US census to compare the first names of Mexican American children born before and after the Gold Rush in California. We find that, even among siblings, children were significantly less likely to receive distinctively Hispanic names if they were born after 1849. Notably, we do not detect the same effects for Mexican American children born in New Mexico, which was annexed to the United States following the Mexican–American War, like California, but which did not experience a similar influx of Anglo settlers during this period, unlike California.

Our results reveal an established population adopting immigrants' cultural practices. They serve as a proof-of-concept for one of new assimilation theory's most important theoretical propositions: that assimilation can involve bidirectional changes, including from an established population toward immigrants. More broadly, and as we discuss in the conclusion, the results qualify the impression – fuelled by social science research on the contemporary United States – that demographic shifts inevitably prompt threat and conflict from established populations. Indeed, under certain conditions, established populations react to numeric displacement with attempts at acculturation.

1.1. Classic assimilation theory

In his canonical theory of assimilation, Milton Gordon described assimilation as a multistage process that begins with acculturation, or an immigrant group's ‘change of cultural patterns to those of [the] host society’ (Citation1964, 71). In Gordon's formulation, acculturation runs in one direction: from the immigrant group to the ‘host’ or ‘core group’ (p. 72), comprised, in the United States, of White Anglo-Saxon Protestants. Although Gordon acknowledged that the core group might change, alongside immigrants, to create a hybrid, ‘cultural blend’ (p. 74), he downplayed the depth of these changes:

Some reciprocal cultural influences have, of course, taken place. American language, diet, recreational patterns, art forms, and economic techniques have been modestly influenced by the cultures of non-Anglo-Saxon resident groups since the first contacts with the American Indians, and the American culture is definitely the richer for these influences. However, the reciprocal influences have not been great. (p. 76)

Instead, Gordon described acculturation as an ‘inevitable tide’ (p. 245) that carries immigrants and especially their children toward an ‘idealised ‘Anglo-Saxon’ model’ (p. 128): ‘Culturally, this process of absorbing Anglo-Saxon patterns has moved massively and inexorably, with greater or lesser speed, among all ethnic groups’ (p. 129).

In characterising assimilation as the end-point of an inexorable, one-way process of acculturation, Gordon diverged from some of his contemporaries, including Brewton Berry, who defined assimilation as ‘the process whereby groups with different cultures come to have a common culture’ (Citation1951, 217), and Joseph Fichter, who defined it as ‘a social process through which two or more persons or groups accept and perform one another's patterns of behaviour’ (Citation1957, 229). In even earlier work, Chicago School sociologists Robert Park and Ernest Burgess described assimilation as ‘a process of interpenetration and fusion’ producing a ‘common cultural life’ (Citation1969 [1921], 735).

1.2. New assimilation theory

Although Gordon's theory came to dominate subsequent assimilation research, it was also met with resistance. Alba and Nee (Citation2003) identify four, main shortcomings of classic assimilation theory. The first is the apparent inevitability and desirability of assimilation. The second is the theory's ‘ethnocentrism,’ which treats White Anglo-Saxon Protestants as the ‘normative standard’ (p. 4). A related shortcoming is that assimilation theory overlooks the possibility that attachment to the ethnic group can facilitate – not simply hinder – mobility. As Alba and Nee explain it, ‘Insofar as individuals and groups retained ethnic cultural distinctiveness, they were presumed to be hampered in achieving socioeconomic and other forms of integration’ (Citation2003, 4).

Segmented assimilation theory partly addressed the ethnocentrism issue by proposing that groups may assimilate into different segments of society (Portes and Zhou Citation1993); similarly, research on ethnic enclaves – like that of Cuban immigrants in Miami – has shown that dense communities of coethnic immigrants can promote economic and other opportunities (Wilson and Portes Citation1980). However, the fourth and final shortcoming of classic assimilation theory remained largely unaddressed prior to Alba and Nee's new assimilation theory, and it boils down to the ‘one-sided nature of the assimilation process’ (Alba and Nee Citation2003, 4).

In response to these shortcomings, new assimilation theory conceptualises assimilation as ‘the decline of an ethnic distinction and its corollary cultural and social differences’ (Alba and Nee Citation2003, 11). Alba and Nee go on to explain that their definition ‘intentionally allows for the possibility that the nature of the mainstream into which minority individuals and groups are assimilating is changed in the process’ (p. 11). In this respect, the authors identify new assimilation theory as the heir to the earlier, Chicago School perspective, which viewed the mainstream as a changing and ‘composite’ culture (see p. 10).

In Rethinking the American Mainstream and later work (Alba Citation2009), Alba articulates assimilation trajectories in terms of ethnic boundary dynamics. He views straight-line assimilation as a case of boundary crossing: ‘individuals move from one side of the boundary to the other through a process that can be likened to conversion,’ that is, by ‘discarding most aspects of their ethnic culture and replacing them with their mainstream equivalents’ (Alba Citation2009, 46). While Alba does not dispute that assimilation can and sometimes does proceed in this fashion, assimilation can also follow boundary blurring if interethnic boundaries become less and less significant as more individuals from visible minority backgrounds ‘[press] into the mainstream’ (p. 47). Critically, this possibility hinges on the mainstream being flexible and capacious, as conceptualised by new assimilation theory.

How does a boundary blur? One avenue is through an expansion of the mainstream to encompass cultural elements that were previously excluded. Alba and Nee (Citation2003), for example, describe how an American mainstream that was seen as Protestant expanded during and after the Second World War to include Catholicism and Judaism. As Alba and Nee point out, however, even in Jewish–non-Jewish marriages, the Jewish spouse is less likely to convert to Judaism than not (p. 93). In other words, religious boundaries blurred through a symbolic expansion of the mainstream to include Jews, Catholics, their offspring and those of interreligious unions; it was not primarily the result of Protestant Americans adopting the beliefs and practices of Judaism or Catholicism.

In some cases, however, a boundary may blur because members of the established population adopt the cultural forms of an immigrant minority. On this point, Alba and Nee (Citation2003, 12–13) provide familiar examples:

The recreational practices of Germans played an important role in relaxing puritanical strictures against Sunday pleasures and left a deep mark on what is now viewed as the quintessentially American culture of leisure…. This influence was in addition to the most obvious cultural borrowing – German Christmas customs, including the decorated Christmas tree.

These and other changes highlight that assimilation occurs not only when immigrants adopt the cultural practices of an established population or when a symbolic boundary expands to include immigrant cultural elements, but also when an established population adopts the cultural practices of immigrants.

1.3. Research on the ‘other side of assimilation’

Alba and Nee proposed a bidirectional model of assimilation, but ‘Remaking the American Mainstream, despite its title, is almost entirely about how immigrants assimilate to America rather than the other side of the equation: how they remake it as well’ (Foner Citation2022, 4). Nevertheless, Foner (Citation2022) contends, past and present immigration flows have profoundly changed American society, for example, in terms of racial composition and beliefs, electoral politics –via new voters, White backlash and ethnic succession–, and other ways. The processes through which immigrants remake the host society, especially through the adoption of newcomers' cultural practices, call for more research (Foner Citation2022, 154).

Tomás Jiménez's The Other Side of Assimilation (Citation2017) is a notable example of such research. The Other Side of Assimilation is an interview study with third-plus generation Americans in Silicon Valley, an area with a sizeable population of Asian and, secondarily, Latino immigrants. Seeking to correct the ‘passive role’ that established populations play in assimilation research (p. 9), Jiménez (Citation2017) proposes the concept of ‘relational assimilation’ to capture the ‘established population's important, but not-so-well documented assimilation to a context heavily defined by individuals who are immigrants or the second-generation children of immigrants’ (p. 3).

However, and despite the fact that first- and second-generation immigrants make up the majority of Silicon Valley residents, Jiménez uncovers only limited change among the established population. On one hand, everyday exposure to newcomers does foster a vision of a kaleidescopic mainstream where ‘strong connections to an ethnic culture’ are normative (Citation2017, 80). On the other, Jiménez's respondents do not adopt newcomers' symbols and practices as their own. As one respondent puts it, they do not ‘take it away, take it home’ (Citation2017, 84).

Instead, public displays of ethnic culture prompt established respondents to long for stronger connections to their own ancestry, which they view as ‘culturally hollow’ by comparison (Jiménez Citation2017, 96). A different response among established respondents is to criticise practices they associate with newcomers. This comes up, for example, in the case of educational achievement, where established respondents do worse compared to newcomers, and particularly Asian students. Some respondents characterise newcomers' parenting practices as ‘strange’ and ‘weird’ (p. 140) and frame their own as ‘normal, and tacitly superior,’ without interpreting ‘the shifting meaning and status of whiteness as a wake-up call to adopt the new norms’ (p. 143).

In sum, the ‘other side of assimilation’ in contemporary Silicon Valley involves many of the same markers listed by Gordon (Citation1964) (‘American language, diet, recreational patterns, art forms’ [p. 76]). Established residents envy and criticise newcomers by turns, while they passively partake of their food and public rituals. And, although they may go out for an ethnic meal, they more rarely adopt immigrants' rituals as their own. In the short term, these changes may appear superficial, but over the long term, they can of course reconfigure American popular culture – and other institutions – in profound and durable ways (Foner Citation2022).

In Silicon Valley, limited adjustment on the part of the established population likely reflects a combination of group size, high status, and broader institutions, three features that modulate the symmetry of relational cultural exchange, according to Jiménez (Citation2017, 12). Indeed, although immigrants and their children were a small majority of Silicon Valley residents when Jiménez was in the field, Silicon Valley was and continues to exist in a broader national context in which later-generation Whites are numerically, culturally, and institutionally dominant.

1.4. Questions and approach

What happens when immigration unfolds more quickly and on a larger scale? In that case, we should expect to see more decisive adaptation from the established population. This would firmly corroborate a core theoretical proposition of new assimilation theory: that assimilation can result from changes that bring an established population in line with the cultural practices of newcomers.

To this end, we explore how Mexican-origin Californios (the established population) responded to the massive in-migration of settlers from the Eastern United States (the newcomers) around the time of the California Gold Rush of 1849. Broadly, we are interested in understanding whether and how much Californios' cultural practices changed following the Gold Rush. Specifically, we examine Californios' naming practices, and we compare these practices to those of the Mexican-origin population in New Mexico, which was also annexed by the United States around the same time, but which did not experience a notable influx of Anglo settlers.

Reviewing research on naming, Sue and Telles (Citation2007, 1385) write, ‘Sociological inquiry into naming practices provides an excellent opportunity to study complex social processes.’ They go on to note, ‘Naming is an especially useful indicator of cultural assimilation because everyone is given a first name, those names are all registered upon birth, and they can be quantified on a continuum from ethnic to nonethnic’ (p. 1387). Indeed, social scientists have looked to names to quantify the cultural adaptation of diverse ethnic groups, including Asian, Black, Jewish, and Mexican Americans (Lieberson Citation2000), Mexican Americans in Los Angeles (Sue and Telles Citation2007), Southwest European, Turkish, and Yugoslav immigrants in Germany (Gerhards and Hans Citation2009), and German Americans following World War I (Fouka Citation2019, Citation2020).

This work distinguishes three general rationales for naming choices. The first is exposure: Immigration exposes established residents and newcomers alike to each other's cultural traits, including their names. Supporting this account, Gerhards and Hans (Citation2009) finds that immigrants who have more German friends are more likely to give their children German first names (also see Lieberson Citation2000). The second rationale is to avoid discrimination. For example, Gerhards and Hans (Citation2009) recount the case of Serbian parents who gave their daughter a name that was common in Germany so that she would not ‘stand out or be disadvantaged’ (p. 1105). Finally, and consistent with a more general motivation to express ethnic belonging via names, Fouka (Citation2020) finds that German Americans chose more German names in response to language restrictions in schools after World War I.

2. Historical case

Although European contact with California dates to the 16th century, Spanish settlement began only in the late 1700s, reflecting the territory's position as a remote province of Spain's New World empire (and later of Mexico). Geographic isolation hindered efforts to attract would-be colonists. However, a population of second-generation native-born Californios had established itself by the time of Mexican Independence, and these numbers would swell to around 7000–8000 during the Mexican period (Pitt Citation1998, 2).

The early 19th century witnessed the introduction of small Anglo elements into Californio society. Most early immigrants – seafarers, shipping agents, and the like – were associated with the maritime trade. They assimilated to the local culture, learned Spanish, ‘swore allegiance to the Mexican Republic, adopted Catholicism, married local women, and obtained legal land grants’ (Pitt Citation1998, 18–19). The situation changed somewhat beginning with the overland arrival of family groups in the early 1840s. Most newer arrivals consisted of farmers and fur trappers who settled in the Sacramento River valley. By and large, they kept to their own communities and did not integrate with the Californios.

While these early Anglo settlers represented a numerical minority in comparison to the population of resident Californios, this situation was to reverse dramatically with the Gold Rush. Pitt (Citation1998, 52–53) estimates that California witnessed the arrival of 100,000 newcomers – including 80,000 Anglos – in 1849 alone. These numbers would continue to swell into the decade.

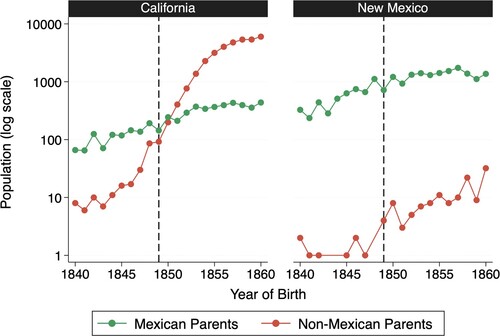

Although we lack yearly figures on the number of new arrivals, we can obtain an approximate picture of the scale of demographic changes by examining the number of children born in California by their date of birth. The left panel of displays these totals (on a log scale) separately for children born to Californio vs. non-Californio parents. Data are drawn from the 1860 census.

Figure 1. Demographic Change in California and New Mexico. The left panel displays the number of children born in California to Mexican vs. non-Mexican parents, by birth year. The right panel displays analogous information for children born in New Mexico. The data are drawn from the 1860 census. We define Mexican parentage as having both parents born in either Mexico or California/New Mexico before 1849.

At the beginning of the period, Californio births outnumber non-Californio births by a factor of ten to one. However, there is a steep rise in the number non-Californio births, and the two lines cross around the year 1850. By the end of the observation period, demographics have shifted completely such that non-Californio births now outnumber Californio by ten to one.

For comparison, the right panel in displays demographic developments in New Mexico Territory, most of which was also annexed by the United States following the Mexican–American War. Here, we observe little change in population shares, and the number of non-Neuvo Mexicanos remains negligible throughout the observation period.

Faced with demographic changes, did Californios feel threatened? Historical evidence indicates that, already in the 1840s, the arrival of Anglo families was a source of considerable consternation. Most salient was a fear of a ‘repeat of Texas’, where numerically dominant Anglos were able to wrest power away from old-line Tejanos. As stated by General Mariano Vallejo ‘if the invasion which is taking place from all sides continues, the Mexican citizens of California will be replaced by or dominated by another race’ (Rawls and Bean Citation2011, 81). Indeed, such fears were realised with annexation and the arrival of the argonauts. The Californio elite would end up losing a vast proportion of their wealth and lands at the hands of Anglo squatters, and ordinary Californios would face discrimination and even collective violence in the gold fields. Against this backdrop, we study Californios' cultural practices, and specifically their naming choices.

The California Gold Rush is a strategic case. On the one hand, it surpassed contemporary migration flows in terms of its speed and scale, allowing us to empirically identify cultural adaptation on a relatively short timescale. On the other hand, although it was fierce and occasionally violent, it was not – from the perspective of CaliforniosFootnote1 – so brutal or oppressive as to defy the very notion of voluntary cultural adaptation (Dunbar-Ortiz Citation2014, 5).

3. Data and methods

Our analyses utilise individual records from the 1860 US census. In particular, our census sample comprises all households containing at least one individual born in either California or New Mexico, as well as a ‘flat sample’ of approximately 20% of remaining census households. The New Mexico sample serves as a counterfactual Hispanic population that was also annexed to the US following the Mexican War, but which did not experience large-scale Anglo immigration. In contrast, the 20% ‘flat sample’ is utilised to construct a benchmark for naming conventions within the non-Hispanic population. Census data are obtained from the Minnesota Population Center and Ancestry.com (Citation2013).

3.1. Identifying Californios

Our task of identifying the Californio population is complicated by the fact that the US census during this period did not contain a separate ‘ethnicity’ question for Hispanic origin. In addition, census enumerators were instructed to classify all Hispanics as ‘white.’ We therefore rely upon place of birth to identify the Californio population. More specifically, we code as Californio all individuals (i) born in California with (ii) both parents born either in Mexico or California/New Mexico before 1849 – that is, while these areas were still under Mexican control.Footnote2

Our decision to utilise information on parental birthplace is informed by several considerations. Most importantly, it allows us to exclude from the Californio population the California-born children of Anglo settlers who began arriving in the early 1840s (because parents' birthplace in such cases would be east of the Mississippi). Further, because we consider the birthplace of both parents, we are able to exclude cases of intermarriage, and focus on the naming decisions of Hispanic couples. Overall, we identify 5,216 individuals as Californios in the 1860 census.Footnote3

3.2. Coding Hispanic names

Our strategy is to compare the first names of children born in California before and after the Gold Rush. We adopt a measure of name distinctiveness first developed by Fryer Jr. and Levitt (Citation2004). Specifically, our Hispanic Name Index (HNI) represents the frequency of a given name among the Hispanic populationFootnote4 relative to its frequency in the American population at large:Footnote5

Note that the HNI is calculated separately for boys and girls and for each year of birth c, such that the information on name frequencies comes only from people born before that year.Footnote6 HNI scores range from 0, representing a name that is present only among non-Hispanics, to 100, representing a name that is present only amongst Hispanics. A score of 50 represents a name that is equally popular in both populations. Overall, we are able to calculate gender-specific HNI scores for 532 unique names covering 3,629 individuals (70%) in our sample of Californio children.

The HNI offers several advantages over manual categorisation schemes employed in prior sociological research (Gerhards and Hans Citation2009; Sue and Telles Citation2007). In particular, these schemes often rely upon subjective judgments about the frequency of a given name – as well as phonetically similar cognates – across cultures. These judgments may differ across researchers. Moreover, in our setting, such judgments likely also reflect contemporaneous notions of whether a name is Hispanic or Anglo, rather than its historical usage. The HNI avoids such anachronism by utilising empirical name frequencies for each birth cohort. In addition, by building frequencies directly into the calculation of the dependent variable, we eliminate the need for subjective judgments entirely, thereby increasing the reproducibility of our research.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive results

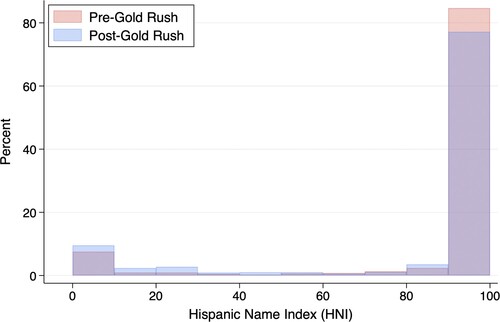

shows the distributions of HNI scores for Californio children born before versus after the Gold Rush. We observe a decline in the percentage of children born after the Gold Rush with highly distinctive Hispanic names (HNI > 90) such as Francisco, Juan, José, Jesús, Dolores, Guadalupe, etc. We can also detect an increase in the frequency of names such as Mary, John, William, Louisa, Caroline, etc. with low HNI scores (HNI < 30).

4.2. Regression results

To assess the statistical significance of these patterns, we next turn to regression analysis. Because parents' naming decisions are likely correlated across children, we nest individual observations within groups of biological siblings.

Model (1) of reports results from a random effects linear regression of HNI scores on an indicator variable for individuals born after the Goldrush. We observe that, on average, parents select names which score about 3 points lower on the HNI scale for children born during or after 1849 (se = 1.19; p < 0.01). In substantive terms, these estimates imply that roughly 3 out of 100 children who would have been named Jesús are instead named John.

Table 1. Regression Results: Effect of the Gold Rush on HNI Scores.

These results provide preliminary evidence of acculturation in response to demographic change. However, we must be careful with our interpretation for several reasons. First, there may be unobserved heterogeneity across families in the propensity to select a Hispanic name. If such heterogeneity is correlated with the timing of births across families, this would introduce bias into our random effects estimates.

A specific case of this phenomenon relates to the arrival of Anglo family groups in the early 1840s. In particular, the California-born children of these settlers may themselves have started having children by 1860. Thus, our coding of Californios may potentially contain some third-generation Anglo immigrants. Further, because third-generation Anglos are likely to appear only around 1860 (because their parents must have been born in the early 1840s), their misclassification as Californios would mechanically result in lower HNI amongst later birth cohorts.

To address this issue (and problems of omitted variable bias more generally), we employ a model with sibling-group fixed effects. The fixed effects model estimates the within-family change in HNI scores between siblings born before versus after the Gold Rush. Such a model avoids misclassifying third-generation Anglos because it is extremely unlikely that a child of settlers who arrived in California in the early 1840s would herself have given birth before 1849. Our fixed effects estimates are reported in Model (2) of . The estimated effect of the Gold Rush is similar to the random effects coefficient ( se = 1.51; p < 0.05).

A second issue relates to the challenge of separating the effects of demographic change from the fact that the Gold Rush occurred almost simultaneously with the annexation of California following the Mexican–American War. Thus, changes in naming patterns may have been a reaction to a change in political boundaries and not solely or primarily to demographic changes due to Anglo immigration.

To account for this possibility, we compare the naming choices of Californios and Neuvo Mexicanos using a difference-in-differences estimation strategy. Most of the territory of New Mexico was also annexed at the same time as California, but New Mexico, unlike California, experienced almost no population inflow during this time (see ). We can therefore use changes in naming patterns among Neuvo Mexicanos as a counterfactual to represent the effect of a ‘pure’ boundary change. The difference-in-difference in pre- versus post-Gold Rush HNI scores between Californios and Neuvo Mexicanos can then interpreted as the effect of demographic change, net of the effect of shifting political boundaries.

Following a similar logic, we can also leverage the fact that Anglo immigration did not proceed evenly over California. In particular, historical sources tell us that Anglos tended to favour settlement in Northern California. In contrast, Southern California offered little attraction before the advent of irrigation and the railroad boom of the 1880s. Pitt (Citation1998, 122) for instance estimates that ‘In 1853 Los Angeles attained a total of 3500 to 4000 souls, including about 300 Americanos; and in 1854 a total of 5000 of whom 1500 or 2000 were resident Yankees…’ This regional variation provides us with a further opportunity to test the specific effects of demographic change, holding political boundaries constant. In particular, we predict that acculturation will proceed most rapidly in Northern California – that is, the area most affected by Anglo immigration.

The results from both difference-in-differences analyses are presented in Models (3) through (8) of . Comparing Californios and Neuvo Mexicanos, we see from Models (3) and (4) that, if anything, Neuvo Mexicano parents reacted to American annexation by choosing slightly more Hispanic names (Model 4: se = 0.44; p < 0.01). Taking this counterfactual into account, our estimate of the Gold Rush effect among Californios even increases in magnitude to around −4.5 HNI points (Model 4:

, se = 1.57, p < 0.01).

From Models (5) through (8), we observe that the average effect for Californios is driven by individuals living in Northern California (Model 6: , se = 2.80, p < 0.01). In contrast, the effect for Southern Californios is much smaller in magnitude and statistically insignificant (Model 8:

, se = 1.79, n.s.). Overall, we take these patterns as evidence supporting our contention that Californios' naming choices reflect specific responses to Anglo immigration rather than contemporaneous political changes.

5. Conclusion

To summarise our findings, following the influx of Anglo settlers during the Gold Rush of 1849, Californios were less likely to give their children distinctively Hispanic names. This result holds even when comparing siblings within the same family who were born before versus after 1849. Moreover, anglicisation was limited to Californios in Northern California, which experienced more Anglo in-migration. By contrast, Mexican-origin Nuevo Mexicanos' naming practices were stable during this period, which suggests that changes among Californios were a response to Anglo in-migration, rather than the territory's concurrent annexation into the United States.

The findings illustrate one of new assimilation theory's most important insights, one that echoes the Chicago School's perspective on assimilation: assimilation entails changes on the part of the established population that bring it closer to immigrants; it is not only or always primarily the result of changes on the part of immigrants themselves. This insight has received sparse empirical attention, with the important exception of Jiménez (Citation2017), who illustrates the ‘other side of assimilation’ in Silicon Valley, an area with a large share of Asian and Latino immigrants. In Silicon Valley, however, the established population did not adopt immigrants' cultural practices as their own, although they consumed immigrant culture, envied it, and criticised it by turns. However, and in contrast to the modest changes identified by Jiménez, the shifts we uncover are consistent with rapid, straightforward cultural adaptation.

A rich literature regards naming practices as indicators of ‘complex social processes,’ chief among them, assimilation (Sue and Telles Citation2007, 1385; also Fouka Citation2019, Citation2020; Gerhards and Hans Citation2009; Lieberson Citation2000). Moreover, the anglicisation of Californios' names illustrates a theorised pathway through which boundaries can blur: through the adoption, by an established population, of immigrants' cultural practices. When they do not focus on the adoption, by immigrants, of the established population's practices, accounts of boundary blurring focus on the symbolic expansion of a boundary to include formerly excluded elements. This was the case, for example, when a Protestant American mainstream expanded around mid-century to symbolically include Catholics and Jews, without sizable conversions among Protestants, Catholics, or Jews (Alba and Nee Citation2003). Instead, in the California case, the established population ‘converted’ to the practices of newcomers.

Our findings also speak to an active literature on how established populations, and in particular US Whites, are reacting to contemporary demographic changes, which have become especially salient following Census Bureau projections that have non-Hispanic, monoracial Whites becoming a numerical minority in coming decades. In general, White people's reactions to perceived changes – ranging from more conservative political positions (Abascal Citation2023; Craig and Richeson Citation2014a; Maggio Citation2021; Wetts and Willer Citation2018), to more negative outgroup attitudes (Craig and Richeson Citation2014b; Outten et al. Citation2012), to stronger identification with other Whites (Abascal Citation2015; Knowles and Tropp Citation2018; Outten et al. Citation2012) and heightened policing of the White boundary (Abascal Citation2020; Cooley et al. Citation2018) – are indicative of attempts by Whites to distance themselves from growing populations. Notably, the Census Bureau projections that are often used to elicit such reactions rest on a narrow definition of ‘Whites’ that excludes Hispanic and multiracial Whites (Alba Citation2018, Citation2020) and reproduce a binary vision of US society that disregards the ‘bridging’ role played by the upwardly mobile children of immigrants (Alba and Maggio Citation2021). These important caveats aside, this literature paints a largely consistent picture of demographic change, one in which an established population reacts to newcomers with attempts to exclude them and distance themselves.

Our findings suggest a different possibility: an established population can react to immigration by aligning their cultural practices with those of newcomers. Why does demographic change lead, in some instances, to distancing and, in others, to alignment? The cases of Anglo immigration to California during the Gold Rush of 1849 and that of contemporary Latino and Asian immigration to the United States are of course different. One notable difference is the sheer volume and speed of Anglo immigration to California: in the space of 20 years, Californio births went from outnumbering Anglo births ten to one, to being outnumbered by them ten to one. By contrast, and despite the fact that some Whites ‘telescope’ Whites' minority status ‘into the very near future, or even the present’ (Alba Citation2018, 1), contemporary demographic changes were precipitated in 1965 (nearly 60 years ago), immigrants have yet to exceed 14 percent of the US population (Budiman Citation2020), and Whites are likely to remain a majority well into the foreseeable future (Alba Citation2018). In sum, the decision to recoil or assimilate may be motivated by a practical consideration: How likely attempts to push away or push out newcomers are to be successful or to antagonise a population whose numeric dominance is inevitable.

This line of thought suggests that power may determine which response flows from demographic threat. Groups who retain significant power – through numeric dominance and/or other advantages – can pursue distancing and exclusion. Those whose power has largely slipped away are better served by defensive strategies that bring them closer to the ascendant group. California's annexation into the United States, which further cemented the Anglo newcomers' political dominance, may have been a contributing factor – if not a sufficient condition – for the adaptive strategy Californios undertook. The intervening role of power may be overlooked in the literature on demographic threat because it focuses primarily on contemporary experiences in North America and Western Europe, where largely White native populations retain significant material, symbolic, and numeric dominance, despite unfolding demographic shifts. Recognizing the role of power allows us to see how populations may pursue adaptive strategies,Footnote7 even in the face of felt threat. Recall that Californios initially viewed Anglo settlement as an ‘invasion’ that threatened their way of life.

Anglo settlers' symbolic and material power also derived from the swiftness and scale of the California Gold Rush. Its speed and scale set the Gold Rush apart from contemporary immigration – making it a strategic case for observing decisive cultural adaptation. However, the Gold Rush also differs from other chapters of settler colonialism in US history,Footnote8 like the Jackson-era forced removal of Native Americans and the American Indian Wars of the 1800s. To interpret the dissolution and absorption of Native American peoples and cultures as ‘cultural adaptation’ or ‘change’ stretches these terms – which imply some agency – beyond recognition (Dunbar-Ortiz Citation2014, 5).

The experience of Californios nevertheless parallels other instances in which once-dominant groups have lost power. Consider for examples David Laitin's account of linguistic assimilation amongst Russian-speakers in Estonia following breakup of the USSR (Laitin Citation1998, Citation2007). Although Russian-speakers constituted the dominant group within the Soviet Union, this was no longer true within the sovereign Republic of Estonia. This reversal of power resembles the fate of the Californios, except that the change was brought by a redrawing of political boundaries rather than an influx of immigrants. Further, the new Estonian government ‘raised the costs for maintaining Russian monolingualism by denying citizenship to any Russian who could not pass an examination in Estonian…[and] making certain jobs available only to Estonian-speakers’ (Laitin Citation2007, 48). While such actions were certainly threatening to Russian-speakers, they nonetheless adopted assimilationist strategies, like their Californio counterparts: ‘Soon there were waiting lists for the few Estonian-medium schools…And summer programs that brought Russian-speakers to Estonian rural areas for acculturation were quickly oversubscribed’ (p. 48).

Following a massive and rapid influx of Anglo settlers, Mexican-origin Californios were less likely to give their children distinctively Hispanic names. The shift exemplifies an established population adopting the cultural practices of immigrant newcomers and validates a key insight of new assimilation theory. It also serves to remind scholars that reactions to demographic changes may be bounded by scope conditions that are rendered invisible by contemporary cases alone.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 From the perspective of California Native people, the Gold Rush brought a ‘true reign of terror,’ killing, by one estimate, 100,000 Native people in 25 years (Dunbar-Ortiz Citation2014, 129).

2 A parallel strategy is employed to identify the population of Neuvo Mexicanos.

3 Unfortunately, we are not able to classify individuals in cases where both parents are not present in the household at the time of census enumeration, because full data on parental birthplace is unavailable. These individuals are therefore excluded from our analyses.

4 We define the Hispanic population based on parental birthplace. Specifically, individuals are coded as Hispanic if both parents are born in Mexico, Spain, Latin America or California/New Mexico before 1848. As before, individuals of mixed parentage are dropped, as are individuals for whom we do not have full parental information. The remaining sample is coded as non-Hispanic.

5 And specifically, in the remaining, non-Hispanic population in the California, New Mexico, and flat samples.

6 Following standard practice, we drop from our calculations ‘rare’ names that occur than 10 times in the 20% sample.

7 Statham (Citation2021)'s study of ‘imported assimilation’ amongst Thai-Western couples provides a contemporary example of how power asymmetries can drive the direction of cultural assimilation as Thai women shift their tastes, identities and lifestyle to accommodate their Western partners. See also Statham (Citation2020).

8 Again, from the perspective of Californios.

References

- Abascal, Maria. 2015. “Us and Them: Black–White Relations in the Wake of Hispanic Population Growth.” American Sociological Review 80 (4): 789–813. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122415587313.

- Abascal, Maria. 2020. “Contraction As a Response to Group Threat: Demographic Decline and Whites' Classification of People Who Are Ambiguously White.” American Sociological Review 85 (2): 298–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122420905127.

- Abascal, Maria. 2023. “Latino Growth and Whites' Anti-Black Resentment: The Role of Racial Threat and Conservatism.” Du Bois Review 20 (1): 21–41.

- Alba, Richard. 2009. Blurring the Color Line: The New Chance for a More Integrated America. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press.

- Alba, Richard. 2018. “What Majority-minority Society? A Critical Analysis of the Census Bureau's Projections of America's Demographic Future.” Socius 4:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023118796932.

- Alba, Richard. 2020. The Great Demographic Illusion: Majority, Minority, and the Expanding American Mainstream. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Alba, Richard, and Christopher Maggio. 2021. “Demographic Change and Assimilation in the Early 21st-Century United States.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119 (13): e2118678119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2118678119.

- Alba, Richard, and Nee Victor. 2003. Remaking the American Mainstream: Assimilation and Contemporary Immigration. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Alba, Richard D., Rubén G. Rumbaut, and Karen Marotz. 2005. “A Distorted Nation: Perceptions of Racial/Ethnic Group Sizes and Attitudes Toward Immigrants and Other Minorities.” Social Forces84 (2): 901–919. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2006.0002.

- Berry, Brewton. 1951. Race Relations: The Interaction of Ethnic and Racial Groups. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co.

- Budiman, Abby. 2020. Key Facts About U.S. Immigrants. Technical report Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/08/20/key-findings-about-u-s-immigrants/.

- Cooley, Erin, Jazmin L. Brown-Iannuzzi, Christia Spears Brown, and Jack Polikoff. 2018. “Black Groups Accentuate Hypodescent by Activating Threats to the Racial Hierarchy.” Social Psychology and Personality Science 9 (4): 411–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617708014.

- Craig, Maureen A., and Jennifer A. Richeson. 2014a. “More Diverse Yet Less Tolerant? How the Increasingly Diverse Racial Landscape Affects White Americans' Racial Attitudes.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 40 (6): 750–761. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214524993.

- Craig, Maureen A., and Jennifer A. Richeson. 2014b. “On the Precipice of a ‘Majority-Minority’ America: Perceived Status Threat From the Racial Demographic Shift Affects White Americans' Political Ideology.” Psychological Science 25 (6): 1189–1197. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614527113.

- Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. 2014. An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Fichter, Joseph H. 1957. Sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Foner, Nancy. 2022. One-Quarter of the Nation: Immigration and the Transformation of America. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Fouka, Vasiliki. 2019. “How Do Immigrants Respond to Discrimination? The Case of Germans in the US During World War I.” American Political Science Review 113 (2): 405–422. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055419000017.

- Fouka, Vasiliki. 2020. “Backlash: The Unintended Effects of Language Prohibition in US Schools After World War I.” The Review of Economic Studies 87 (1): 204–239. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdz024.

- Fryer Jr., Roland G, and Steven D Levitt. 2004. “The Causes and Consequences of Distinctively Black Names.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 119 (3): 767–805. https://doi.org/10.1162/0033553041502180.

- Gerhards, Jürgen, and Silke Hans. 2009. “From Hasan to Herbert: Name-Giving Patterns of Immigrant Parents Between Acculturation and Ethnic Maintenance.” American Journal of Sociology114 (4): 1102–1128. https://doi.org/10.1086/595944.

- Gordon, Milton M. 1964. Assimilation in American Life: The Role of Race, Religion, and National Origins. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Jiménez, Tomás R. 2017. The Other Side of Assimilation: How Immigrants are Changing American Life. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Knowles, Eric D., and Linda R. Tropp. 2018. “The Racial and Economic Context of Trump Support: Evidence for Threat, Identity, and Contact Effects in the 2016 Presidential Election.” Social Psychological and Personality Science 9 (3): 275–284. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550618759326.

- Laitin, David D. 1998. Identity in Formation: The Russian-Speaking Populations in the Near Abroad. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Laitin, David D. 2007. Nations, States, and Violence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lieberson, Stanley. 2000. A Matter of Taste: How Names, Fashions, and Culture Change. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Maggio, Christopher. 2021. “Demographic Change and the 2016 Presidential Election.” Social Science Research 95:102459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2020.102459.

- Minnesota Population Center and Ancestry.com. 2013. “IPUMS Restricted Complete Count Data: Version 1.0 [Machine-Readable Database].”

- Outten, H. Robert, Michael T. Schmitt, Daniel A. Miller, and Amber L. Garcia. 2013. “Feeling Threatened About the Future: Whites' Emotional Reactions to Anticipated Ethnic Demographic Changes.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 38 (1): 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211418531.

- Park, Robert E., and Ernest W. Burgess. 1969 [1921]. Introduction to the Science of Sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Pitt, Leonard. 1998. Decline of the Californios: A Social History of the Spanish-Speaking Californians, 1846–1890. Berkeley, CA: Univ of California Press.

- Portes, Alejandro, and Min Zhou. 1993. “The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and Its Variants.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 530 (1): 74–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716293530001006.

- Rawls, James J., and Walton Bean. 2011. California: An Interpretive History. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Statham, Paul. 2020. “Living the Long-term Consequences of Thai-Western Marriage Migration: the Radical Life-course Transformations of Women Who Partner Older Westerners.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (8): 1562–1587. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1565403.

- Statham, Paul. 2021. “‘Unintended Transnationalism’: The Challenging Lives of Thai Women Who Partner Western Men.” Population, Space and Place 27 (5): e2407. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.v27.5.

- Sue, Christina A., and Edward E. Telles. 2007. “Assimilation and Gender in Naming.” American Journal of Sociology 112 (5): 1383–1415. https://doi.org/10.1086/511801.

- Wetts, Rachel, and Robb Willer. 2018. “Privilege on the Precipice: Perceived Racial Status Threats Lead White Americans to Oppose Welfare Programs.” Social Forces 97 (2): 793–822. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soy046.

- Wilson, Kenneth L., and Alejandro Portes. 1980. “Immigrant Enclaves: An Analysis of the Labor Market Experiences of Cubans in Miami.” American Journal of Sociology 86 (2): 295–319. https://doi.org/10.1086/227240.