ABSTRACT

The descendants of immigrants have become increasingly successful in Western European education systems and labor markets, which in principle supports Richard Alba’s new assimilation theory (NAT). Still, acceptance and recognition on the part of the mainstream has not kept pace. We have suggested outgroup mobility threat (OMT), the fear of being overtaken by intergenerational mobility, as one possible explanation. However, Richard Alba has argued that demographic changes widely lead to a non-zero-sum mobility and do not necessarily cause competition threat. In this paper, we relate Richard Alba's reasoning to the concept of OMT, focusing on the German immigration context. We bring together the arguments by distinguishing between realistic and symbolic threat and by differentiating between occupations and groups. We measure OMT and test our hypotheses using a vignette study that we recently conducted as part of the kick-off survey of the new National Discrimination and Racism Monitor (NaDiRa) in Germany. Our results confirm that Richard Alba's argument is superior to the simple competitive threat perspective. However, we also show that it is still insufficient, and OMT comes into play when immigrant groups move up into value-based occupations that are assumed to normatively shape society. Moreover, we demonstrate that this threat is felt particularly when Muslims ascend to these types of occupations.

Introduction

Looking at recent trends in contemporary Western European migration societies, research reveals an interesting and somewhat puzzling pattern of developments: On the one hand, there is strong, not to say overwhelming, evidence that integration, in its structural, cultural, and social components, is clearly progressing over time and especially across generations. This is true for different countries and for very different aspects of integration (Alba and Foner Citation2015; Kalter et al. Citation2018), including the structural domains of education systems and labour markets (Heath and Cheung Citation2007; Heath and Brinbaum Citation2014), which are widely considered to be of central importance. On the other hand, anti-immigrant attitudes, essentially based on the narrative that immigrants and their descendants would be unwilling or unable to integrate, appear to be remarkably persistent (Czaika and Lillo Citation2018; Dennison and Dražanová Citation2018), if not even on the rise (Meuleman, Davidov, and Billiet Citation2018; Küpper, Krause, and Zick Citation2019). This is especially true for anti-Muslim attitudes (Bell, Valenta, and Strabac Citation2021; Bertelsmann Stiftung Citation2015; Decker et al. Citation2022, 72; Gorodzeisky and Semyonov Citation2019), which have played a dominant role in European discourse in recent decades. Hostile attitudes toward Muslims are often most pronounced when compared to those toward other minority groups (Zick and Krott Citation2021).

These trends and observations are also ambiguous in the light of new assimilation theory, as put forward very prominently by Richard Alba. Basically, it is argued that assimilation as a revised and refined analytical-descriptive concept, understood as the decline of ethno-racial distinctions and their impacts, is a very likely process, especially in the structural realm (Alba and Nee Citation1997; Citation2003). This is widely supported by research (Drouhot and Nee Citation2019; Waters and Pineau Citation2015; White and Glick Citation2009). However, Richard Alba and his co-authors have also emphasised the two-sided nature of the process and that it also includes acceptance on the side of mainstream society (Alba and Foner Citation2015). The fact that intergenerational mobility and structural assimilation trends are not accompanied by respective recognition tendencies on the part of the dominant society thus poses a challenge also to new assimilation theory.

In previous papers, we have suggested outgroup mobility threat (OMT) as a mechanism that can contribute to the list of possible explanations for recognition gaps, especially for anti-Muslim attitudes (Foroutan et al. Citation2019; Foroutan and Kalter Citation2021). OMT reflects a variant of the ‘integration paradox’ (Verkuyten Citation2016) and means that the dominant society, or what Alba calls the ‘mainstream’, may develop negative attitudes toward immigrant and minority groups precisely because they are increasingly better structurally integrated. Intergenerational mobility can lead to a threat of being overtaken. But, as Richard Alba has also emphasised in much of his recent work, things are not so simple. It is questionable whether the structural mobility of the descendants of immigrants really causes competition and threat. Overall demographic changes are leading to what Richard Alba has called ‘non-zero-sum’ mobility (Alba Citation2020; Alba and Maggio Citation2022). But this makes the persistence of hostile attitudes towards minorities even more puzzling.

In this paper, we confront threat-theoretical arguments with Richard Alba's non-zero-sum argument and seek to develop these concepts and our construct of OMT further to understand the puzzle outlined. Building on the distinction between realistic and symbolic threat (Stephan and Stephan Citation2000) and related theoretical approaches, we argue that it can make a difference whether minority mobility is only about relative resources or whether it also affects values, norms, and habits, i.e. the shape of society and its ‘rules of the game’.

In the following, we explain and develop the theoretical ideas in more detail. We then derive hypotheses about which occupational characteristics might have an impact on OMT and for which minority groups this impact might be stronger. We measure OMT and test the hypotheses using a vignette study that we recently implemented in a submodule of the new National Discrimination and Racism Monitor (NaDiRa) in Germany, which is conducted by the German Center for Integration and Migration Research (DeZIM Institute). We present our main findings and discuss their implications for Richard Alba’s reasoning.

Theory and past research

New assimilation theory and its evidence

New assimilation theory as proponed by Richard Alba (Alba and Nee Citation1997; Citation2003) has made many fundamental clarifications and corrections to classical assimilation theory (e.g. Park Citation1950; Gordon Citation1964). Above all, it has emphasised that assimilation – in its core defined as ‘the attenuation of an ethnic or racial distinction and the cultural and social differences that are associated with it’ (Alba and Nee Citation1997, 834) – is to be understood as an analytical, descriptive concept, and that two accentuations are especially important: First, assimilation is no longer seen as an inevitable, law-like quasi-linear process, but as contingent, and outcomes may vary across contexts, groups, and dimensions of assimilation. However, it is still argued that, given general mechanisms of action and interaction (Nee and Alba Citation2013; Kalter Citation2022), there is much reason to believe that assimilation is very likely under the conditions of most modern migration societies, especially with respect to the important structural dimension. Second, it is stressed that assimilation is to be understood as a two-way process and not as a unilateral adaptation on the side of the immigrant minorities only.

In later work, Richard Alba has also occasionally switched to the concept of integration. He and Nancy Foner have argued that there is considerable overlap between the revised assimilation concept and the concept of integration, which is commonly favoured in the European context (Alba and Foner Citation2015). Within this outline, they have suggested the following definition:

‘Integration’, as we understand it, refers to the processes that increase the opportunities of immigrants and their descendants to obtain the valued ‘stuff’ of a society, as well as social acceptance, through participation in major institutions such as the educational and political system and the labor and housing market. (Alba and Foner Citation2015, 5)

It is safe to say that the first key view of new assimilation theory is strongly supported by research on mobility processes among disadvantaged minorities in Western societies (Alba and Foner Citation2015; Kalter et al. Citation2018), especially with respect to the structural areas of education and the labour market (Heath and Brinbaum Citation2014; Heath and Cheung Citation2007). Intergenerational trends are not least driven by high aspirations (Kao and Tienda Citation2012; Salikutluk Citation2016) and positive choice effects (Jackson, Jonsson, and Rudolphi Citation2012; Dollmann Citation2017) that contradict the narratives of the unwilling, non-integrable minorities who would finally end up as fiscal burdens, as employed by the populist right. At the same time, however, these right-wing populist parties have successfully built election campaigns on anti-immigrant strategies, and negative attitudes against immigrants have risen in many countries rather than declined (Meuleman, Davidov, and Billiet Citation2018; Küpper, Krause, and Zick Citation2019). So the recognition processes on the side of the mainstream population have by no means kept pace with the structural mobility processes on the side of most minorities.

Outgroup mobility threat and non-zero-sum mobility

There are many factors and arguments to explain anti-immigrant attitudes and some exogenous trends could be natural confounders to the recognition of the structural successes of the minorities. Explanations refer, for example, to economic crises (Billiet, Meuleman, and Witte Citation2014; Kuntz, Davidov, and Semyonov Citation2017; Meuleman, Davidov, and Billiet Citation2018) or growing polarisation due to the dynamics of social or traditional media (Štětka, Mihelj, and Tóth Citation2021). An interesting line of argumentation regards the trends as something that might partly be endogenous to the processes of structural integration. Some scholars argue that expectations on both the migrant and non-migrant side increase as adaptation progresses (Dixon et al. Citation2010; Tolsma, Lubbers, and Gijsberts Citation2012; Foroutan Citation2012; Ten Teije, Coenders, and Verkuyten Citation2013; Canan and Foroutan Citation2016; El-Mafaalani Citation2018). The migrants and their descendants perceive lack of recognition more strongly when they are better integrated and react more sensitively to devaluations and a lack of equality which can lead to a kind of ‘integration paradox’ when they withdraw into ethnic enclaves (Verkuyten Citation2016; De Vroome, Martinovic, and Verkuyten Citation2014; Schaeffer Citation2014; El-Mafaalani Citation2018) or use strategies of identity politics (Attia Citation2014; Dotson Citation2018). But there might also be another understanding of ‘integration paradox’ redirecting it towards the non-immigrant majority society that reacts with aversion and fear of status when immigrants integrate and ascend into power (Sutterlüty Citation2010; Foroutan Citation2019, 145f; El El-Mafaalani Citation2018). In other words, some members of the majority population may develop negative attitudes toward immigrant and minority groups, not because they are unable or unwilling to integrate, but precisely because they succeed in doing so.

This connects to traditional theories of ethnic competition and threat (Sherif and Sherif Citation1969; Blalock Citation1967; Blumer Citation1958), which assume that there is a basic conflict over scarce resources. In its classical understanding, however, the threat is usually related to new immigrants entering a society. To address the specific threat that might stem from the intergenerational mobility of longer settled immigrant groups, we suggested the concept of outgroup mobility threat (OMT). OMT, in other words refers to threats that are caused by the growing structural success of migrant and minority groups. The concept relates to Honneth and Sutterlüty (Citation2011), who have already addressed the idea that the rise to power of formerly marginalised groups is only accepted to a certain extent. We were able to show that OMT helps us to understand anti-Muslim attitudes in Germany independently of other factors (Foroutan et al. Citation2019; Foroutan and Kalter Citation2021).

However, in much of his recent work Richard Alba has emphasised that there should be a strong demographic force working against competition threat mechanisms in most Western societies (Alba Citation2020: Alba and Maggio Citation2022). As the dominant cohorts of the baby boomers are about to leave the labour market and as the younger cohorts have become increasingly diverse, many vacancies will appear, fostering ample opportunities for structural assimilation. This holds true also for the labour market in Germany (Baumann et al. Citation2019). Richard Alba speaks of ‘non-zero-sum mobility’, emphasising that there is no longer tight competition as the formerly largely White mainstream will not be able to refill these positions anyway.

Given these seemingly conflicting lines of reasoning – OMT vs. non-zero-sum mobility –, it is useful to refine and develop the arguments and concepts further. A fruitful starting point is to ask whether the logics of outgroup mobility threat or non-zero-sum mobility apply in principle to all kinds of occupations, or whether the arguments apply only to some but not to others. Here, the distinction between realistic and symbolic threat within the general framework of threat theory (Stephan and Stephan Citation2000) becomes important. Roughly speaking, realistic threat refers to the material situation and results from competition for scarce resources, while symbolic threat concerns cultural values, shared norms and beliefs, and agreement on the ‘rules of the game’ in a society (Campbell Citation1965; Stephan, Ybarra, and Morrison Citation2009; Stephan and Stephan Citation2017). From a more general theoretical perspective, one could say that realistic threat is about relative access to resources, while symbolic threat is about social production functions that determine the value of resources (Lindenberg Citation1989; Kalter and Granato Citation2002; Kalter Citation2022). This also relates to the juxtaposition of the ‘economic insecurity perspective’ and the ‘cultural backlash thesis’ (Inglehart and Norris Citation2017; Chung and Mau Citation2014; Lengfeld and Ordemann Citation2017) to explain the recent rise of the populist right.

While both realistic and symbolic threat usually contribute to explaining patterns of anti-immigrant/minorities attitudes, symbolic threat is often seen as being especially important in wealthy Western European countries (Davidov et al. Citation2020; Uenal Citation2016), where the competition is not mainly about shelter, food or personal security but more about personal freedom, expression and the quality of democracy (Inglehart and Norris Citation2017; Mudde Citation2021). Here competition between norms and lifestyles (Hochschild Citation2017; Kaschuba Citation2016) leads to a struggle for cultural sovereignty and a polarisation of society along the lines of pro- and anti-plurality (Foroutan Citation2019).

There is reason to assume that realistic threat might indeed be reduced by the rising number of job vacancies due to demographic change. The fact that upward-mobility of formerly underprivileged groups improves their material situation does not necessarily come at the cost of the already privileged mainstream members, at least not in absolute terms. And, as the pandemic has shown, a number of highly ‘system-relevant’ occupations are already over-proportionally filled by people with immigrant backgrounds (Khalil, Lietz, and Mayer Citation2020). Many high-ranking positions, e.g. physicians, are obviously system-relevant too. So, there is much room for win-win rather than non-zero-sum. However, the story is likely to be different for symbolic threat. Even if one’s material situation is not directly threatened by minority groups climbing up the social ladder, the fact that they might enter occupations that are involved in shaping and maintaining the values and rules of a society might feel threatening, as these values and rules have ensured one’s position and privileges in society so far.

The German context and the specific role of anti-Muslim sentiment

The threat posed by different minority groups may be perceived differently, depending on historical conditions or the context of their immigration, their demographic and socioeconomic selectivity, or perceived cultural distance. Minority group boundaries can be based on various characteristics, such as country of origin, religion, or skin colour, and are inherently blurred and fluid (Brubaker Citation2002; Wimmer Citation2008).

In Germany, people with a Turkish background are the largest group that is often distinguished. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Turkey became the main country of origin for the recruitment of guest workers in Germany, especially for low-skilled labour. Due to the dynamics of family reunions, transnational marriages, and other events, Turkey was still the most common country of origin (more than 2.7 million) among people with a migration background as defined by the Federal Statistical Office in 2021 (BMI/BAMF Citation2022, 172). Turkey is by far the leading country of origin among those who belong to the second generation in Germany.

Available estimates based on survey data suggest that about 90% of people with a Turkish background in Germany are Muslims (including Alevis) (Kalter and Heath Citation2018, 74; Schührer Citation2018, 25).Footnote1 The importance of this religion-based categorisation has increased enormously, as in many other countries, at the latest since September 11 (Mudde Citation2021). After Turkey, Kazakhstan (just under 1,3 million) and Syria (just under 1,1 million) account for the largest Islamic-shaped countries of origin in Germany (BMI/BAMF Citation2022, 172), with most Syrians having arrived as war refugees only since 2014. Other Islamic-shaped countries of origin with notable shares are, for example, Iraq, Afghanistan, Iran and Morocco. According to projections, between 5.3 and 5.6 million Muslims lived in Germany in 2019 which accounts for 6.4%–6.7% of the population (Pfündel, Stichs, and Tanis Citation2021).

In recent decades discussions about the claims of cultural, ethnic, religious, and national minorities have focused heavily on Islam and Muslims. Not only in Germany, but also in other European countries, Muslim immigration has increased (Pew Research Center Citation2017), coupled with high levels of anti-Muslim hostility (Bell, Valenta, and Strabac Citation2021; Gorodzeisky and Semyonov Citation2019). While Muslims invoke fundamental rights in almost all European constitutions that grant them religious freedom and the right to visibly practice their rites, they shape everyday life in public schools, cities, and workplaces by making concrete demands, such as eating halal food, building mosques, or going to work wearing headscarves or other visible signs of religiosity. In largely secular Western Europe, they challenge the existing habits and norms of society by demanding not only representation but also the right to reshape the society in which they live. And they are better able to do so the higher they are on the social ladder. In doing so, they contest the privileges of the established majority society that sets the ‘rules of the game’, which has led to constant debates about whether Islam and Muslims ‘belong’ to Germany, France, the Netherlands, etc. (Korteweg and Yurdakul Citation2014; Olgun Citation2015; Thomas Citation2011). In parallel, however, this has also led to Muslims fighting for their rights not only in the (pop)cultural and public spheres, but also in the political sphere, resulting in Muslims being the largest minority group in German parliaments at the federal and local levels (Hughes Citation2016; Schönwälder, Sinanoğlu, and Volkert Citation2013; Wüst and Bergmann Citation2023). As a result, people who represent ‘(…) sectors that were once culturally dominant in Western Europe may react angrily to the erosion of their privilege and status’ (Inglehart and Norris Citation2016, 3).

The data we will describe and use in the following will allow us to compare the threat felt from the social mobility of Muslims in comparison to other groups that are relevant in the German context. In addition to Islamophobia, the German government’s National Action Plan against Racism cites anti-Semitism, antiziganism, and anti-Black racism as particularly virulent forms of racism in Germany (Bundesregierung Citation2017). In the pandemic, anti-Asian racism also gained prominence and attention (Suda, Mayer, and Nguyen Citation2020), challenging the perception of Asians as a ‘model minority’. Due to the Nazi past, anti-Slavic racism in Germany deserves special attention, and immigrants from Eastern Europe dominated German immigration in the decades following the recruitment of guest workers. After Turkey, Poland (nearly 2.2 million) and Russia (about 1.3 million) are the second and third countries of origin for people with a migration background in 2019 (BMI/BAMF Citation2022, 172) and Romania is sixth (about 1 million).

Research questions and hypotheses

In this paper we study the acceptance of structural integration by analyzing outgroup mobility threat (OMT) with respect to different minority groups when these enter specific job positions in the German labour market. We focus on three different set of questions:

First, we are interested in group differences, i.e. whether OMT is felt more strongly when it relates to specific minority groups. More precisely, we are interested in how far the evidence for OMT is stronger when it comes to Muslims. As the discussion in the last section has shown, there are theoretical reasons and empirical hints that lead one to expect that this is the case in the context of the German discourse. We formulate this as the first hypothesis:

▪ H1: OMT is perceived more strongly in relation to Muslims than in relation to other minority groups in Germany.

Second, we are interested in differences between occupations. As outlined in the theoretical discussion above, not all kinds of job mobilities might pose the same amount of threat nor are they contested in the same way. The different theoretical perspectives lead to three different basic hypotheses:

⚬ Mere-competition hypothesis: Realistic threat theory and the general ‘economic insecurity perspective’ would lead to the conclusion, that minorities are welcome in the labour market as long as they do not challenge one’s own status. Accordingly, one would expect:

▪ H2: OMT is stronger for occupations with higher socio-economic status.

⚬ Non-zero-sum hypothesis: The structural assimilation perspective of Richard Alba suggests that the acceptance of minorities is not so much connected to status per se, but that it should be higher in occupations where a shortage is felt due to the general demographic changes. In other words:

▪ H3: OMT decreases with the perceived shortage in occupations.

⚬ Value-shaping hypothesis: Symbolic threat theories, the emphasis on values in the concept of social production functions and the ‘cultural backlash’ perspective, emphasise that social mobility is not only about the overall economic welfare but might also be considered as a threat because it challenges the ‘rules of the game’ and thus the value of one’s own resources and privileges. Accordingly, one would expect that:

▪ H4: OMT increases in those professions that play a role in shaping and upholding society's values and institutional rules.

Third, we are interested in whether there are interactions between minority groups and occupations; in particular, we ask whether H4 holds especially strongly for Muslims.

▪ H5: OMT is highest when Muslims enter professions that play a role in shaping and upholding society's values and institutional rules.

Data and methods

The data for our analyses come from the kick-off study (DeZIM Citation2022) of the National Discrimination and Racism Monitoring (NaDiRa) in Germany which is run by the German Center for Integration and Migration Research (DeZIM). It is based on a representative CATI survey in Germany, which was conducted between April and August 2021. The fieldwork of the study was carried out by the BIK Aschpurwis + Behrens GmbH. The target population of the survey is the German-speaking population living in private households aged 14 and over. The sample was drawn according to the usual ‘dual frame’ approach, which combines landline and mobile numbers (Häder and Häder Citation2014). The data set contains 5,003 interviews (for more details see: BIK Citation2021).

To capture group- and occupation-specific outgroup mobility threat (OMT), a factorial design module was implemented. The respondents were asked to evaluate vignettes of the following type combining three factors:

Different groups are more or less well represented in different areas of society. How good or bad would you find the following developments? Would it be very good, fairly good, neither good nor bad, fairly bad or very bad if more #factor1(minority groups) #factor2(gender specification) worked in/as #factor3(occupations).

Table 1. Occupational categories chosen for the vignettes.

We covered four different areas of the labour market, namely private production and services, medical sector, public sector, and political sector. In each we chose both higher status and also lower or medium status occupations which results in the eight cells of . In four of these eight cells we considered two different occupations, so that we included 12 occupations in total.

All respondents received eight vignettes, each of them covering a different cell of for factor3. In the cells containing two occupations, one of these was selected randomly. Minority groups (factor1) and gender specification (factor2) were randomly selected. For the analyses we only use the vignettes in which one of the seven minorities is inserted. These are 30,276 vignettes in total.

Note that the sample representing the (German-speaking) population in Germany naturally contains a number of respondents who, depending on the operationalisation, fall into one or more of the specified minority group categories. For instance, 100 respondents self-identify as ‘Asian’, 42 as ‘Jewish’, 243 as ‘Muslim’, 24 as ‘Sinti or Roma’, 250 as ‘Eastern European’, 63 as ‘Black’, and 127 were born in Turkey or have at least one Turkish-born parent. Overlaps, i.e. multiple group memberships, are possible. In total there are 736 vignettes in the analyses where the respondent is a member of the group specified in the vignette formulation. This is only a very small proportion (2.4%) of all vignettes. We decided to leave them in the analyses; we checked and found that dropping them would not lead to any substantive change of the results in this paper.Footnote3

We measure OMT by the share of those who evaluate a vignette either by ‘bad’ or ‘very bad’. In general, the evaluation answers to the vignettes show an uneven distribution with a clear break between the first three answer categories (very good, good, neither good nor bad) and the remaining two (bad, very bad).

To analyze the effect of vignette factors we run linear probability models estimating robust standard errors accounting for the clustering along respondents (see Appendix ). To ease the interpretation of the coefficients, we multiply the dependent OMT variable by 100; thus the coefficients of the independent variables can be read as a change in percentage.

To measure the status of an inserted occupation we use the International Socio-economic Index of Occupational Status (ISEI) (Ganzeboom, De Graaf, and Treiman Citation1992). contains the corresponding values of the occupations in brackets.Footnote4 To measure the societally perceived shortage in occupations, we make use of the fact that the data also contains vignettes with no minority group specification at all, but just insert an empty category for factor2. Accordingly, the vignettes reduce to, for example: ‘Would it be very good, fairly good, neither good nor bad, fairly bad or very bad if more people (woman, men) would work as nurses’. We use the percentage of ‘very good’ answers as a measure for the subjectively perceived shortage in an occupation. The respective percentages for the 12 occupations range from 14.9% (office clerks) to 41.9% (nurses). We use a dummy variable to indicate whether an occupation is one of the six in belonging to either the public or the political sector, as these are especially involved in the shaping or maintenance of societal norms, values and rules.

Results

Group differences

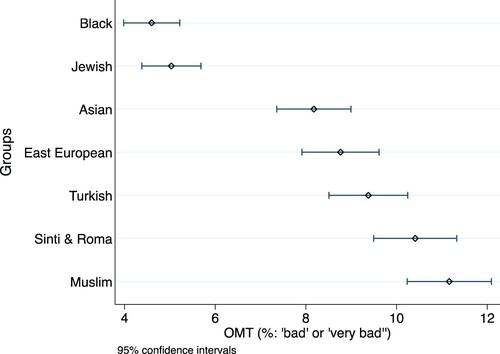

analyzes the differences between the minority groups over all gender specifications and occupations. The first thing to notice is that, overall, the share of aversive answers is relatively low. Summing up all minority groups included, 8 percent of all vignettes are evaluated with either ‘bad’ or ‘very bad’.Footnote5 However, there are clear differences between the minority groups.

While there is only little aversion to Black (4.6%) or Jewish (5.0%) people in the presented occupations, there is a significantly higher disapproval of the other five groups. The highest OMT shares are found towards Muslims (11.1%), followed by Sinti and Roma (10.4%), Turkish (9.4%), East European (8.8%) and Asian (8.2%).Footnote6

confirms hypothesis H1 which expects the OMT with respect to Muslims to be especially strong. As the confidence intervals in the figure suggest, and as Model 1 (Appendix ) confirms, the difference to almost all other groups is highly significant, Sinti and Roma being the only exception.Footnote7

Differences between occupations

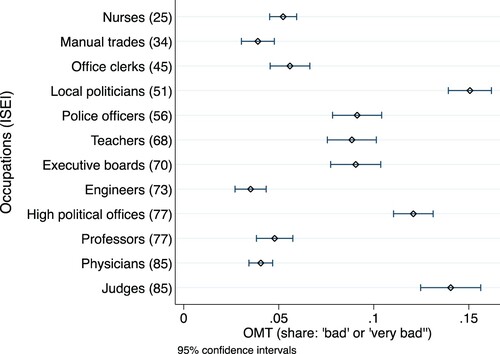

Turning to the differences between the occupational categories, shows the OMT shares summing up all minority groups combined. The occupations are ordered by their ISEI score which is given in brackets.

We find that there are huge differences in OMT between the different occupations, with the largest resistance against the minority groups assuming the functions of local politicians or judges. At the other extreme, only a tiny share of respondents dislikes them in manual trades or as engineers.

Testing the mere-competition hypotheses

According to hypothesis H2 there should be higher OMT in occupations with higher ISEI score. But this does not really seem to hold true when checking by eye. Most strikingly, OMT is high for ‘local politicians’ and low for ‘engineers’, ‘professors’, and ‘physicians’. There is also no clear pattern when comparing low or medium status occupations to high status occupations in the separate areas of the labour market. ‘Engineers’ receives even somewhat lower OMT than ‘manual trades’ or ‘office clerks’, ‘physicians’ even less than ‘nurses’, ‘professors’ less than ‘teachers’, and ‘high political offices’ less than ‘local politicians’.

Still, in a regression using all vignettes, controlling also for the group and gender specification of the vignette, the ISEI score of the occupation given in the vignette has a positive effect (see , Model 3 in the Appendix). This means that there is a tendency for OMT to be somewhat larger for higher status occupations. The effect is significant on a high level (p < .001); however, the number of observations (vignettes included in the analyses) is very large, and the actual effect size is rather weak: the probability of OMT rises by 0.03% with one unit of the ISEI score, which for the full range of ISEI scores included (25–85) can only account for a difference of 1.8%. Including the ISEI score also does not increase the explanatory power of Model 1 without it. In comparison, including the occupations as dummies in Model 2 increases the R2-value by more than a factor of 3.

In sum, there is only weak support for hypothesis H2. We conclude that a mere realistic competition view is far from sufficient to understand the patterns of resistance against minority groups being more integrated in different occupations.

Testing the non-zero-sum hypothesis

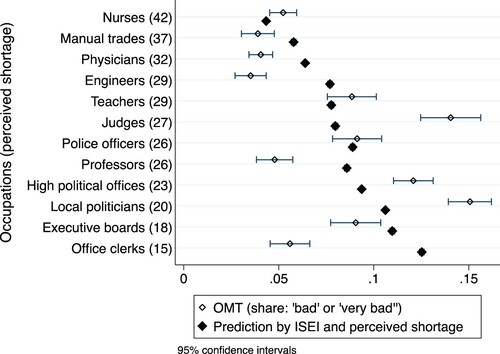

To test hypothesis H3, which is derived according to the non-zero-sum argument by Richard Alba, we add the perceived shortage to the regression (Model 4 in Appendix ). The explanatory power of the model rises. The variable has a negative effect of −31.2, which is significant on a high level. This means that an increase of one unit in perceived shortage would decrease OMT by 31.2%. Note that perceived shortage is measured as a percentage, so a unit reflects 100%. Still, the range of the variable (from 14.9% to 41.9%) covers 27% which yields a difference of 8.4% in the predicted OMT value.

illustrates the OMT differences between occupations again, but now ranked according to the perceived shortage. As compared to , a kind of trend is more clearly detectable. also shows the values predicted from the regression including the perceived shortage (Model 4 in Appendix ). The graph confirms that the model can capture some of the differences between the occupations. It also shows, however, that the actual OMT patterns partly still deviate greatly from the prediction.

Figure 3. OMT differences between occupations ranked by perceived shortage.

Data: NaDiRa kick-off study.

We conclude that the perceived shortage in occupations explains the differences in OMT for minority groups much better than the status, and that thus the demographic non-zero-sum argument expressed in H3 is generally supported. However, it still does not seem to grasp some major OMT differences between the occupations sufficiently.

Testing the value-shaping hypothesis

As a next step in our regression analyses of the vignettes, we add a dummy variable indicating whether an occupation is one of the six in the public or political sector (see ), and thus involved in the shaping and consolidating of societal values and rules. We find that this adds significantly to the explanation (see Model 5 in Appendix ). The coefficient tells us that, controlling for the other variables, OMT is on average 5.7% higher for value-related occupations as compared to the others. Including this variable also leads to a substantive increase in the R2-value.

Thus, hypothesis H4 is basically supported, and it seems that the value-shaping argument adds to the non-zero-sum argument. The inclusion of the value dummy reduces the effect of the perceived shortage variable, but the latter still contributes significantly to Model 5.

Interactions between groups and occupations

In the last step of our analyses, we address hypothesis H5 and investigate to what extent there is a specific OMT posed by Muslims when it comes to value-shaping occupations. To assess this, we add an interaction of the dummy variable for the public and political sector occupations with the dummy for the Muslim category and also with the dummy for the Turkish group to the regression (Model 6).Footnote8 We find that next to the positive main effect of the public and political sector, both interactions have a highly significant positive effect, the one for Muslims being stronger than the one for Turkish.Footnote9 This means that there is a specific OMT when respondents think of Turkish people, and even more so if they think of Muslims in these kinds of occupations.

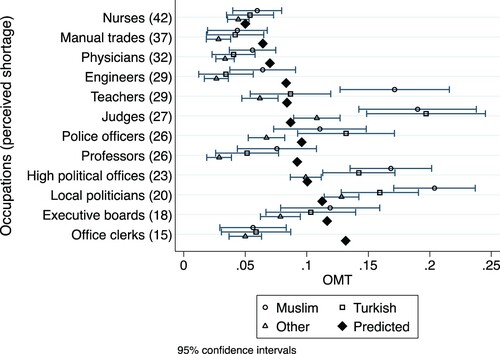

shows this in more detail. It compares the vignette answers for the different occupations between respondents asked about Muslims, Turkish people and the other groups. In addition, the figure contains the predicted OMT values from Model 4 (Appendix ), i.e. based on a regression on the occupations’ ISEI-scores and the perceived shortages.

Figure 4. OMT relating to Muslims and Turkish people compared to OMT relating to the other groups and to model predictions.

Data: NaDiRa kick-off study.

Interestingly, perceived OMT relating to Muslims and Turks does not differ significantly from that perceived with respect to the other groups in five of the six non-value-shaping occupations. There is a notable difference between Muslim and the others in the occupation ‘engineers’, but OMT is on a comparably low level here and the estimate for Muslim is still in the range of the value predicted by the ISEI score and the perceived shortage. The estimate for the category Turkish is in line with the estimate for the category ‘other’ even in all six non-value-shaping occupations.

Things are different in five of the six value-shaping occupations, professors being the only exception. There is a clearly higher OMT for Muslims in the occupation ‘teachers’, while the estimates for Turkish and other are in the range of the predicted value. For judges, the estimates for both Muslim and Turkish not only by far exceed the predicted values, but also the estimate for the group ‘others’. When it comes to police officers, there is no OMT higher than predicted for the ‘others’, but the category Turkish differs significantly, and the category Muslim is also (though not significantly) on a much higher level. For the occupations of high political offices and local politicians, we observe a slightly higher OMT than predicted for the others, a clearly higher value for Turkish, and a much higher value for Muslims.

There is, thus, a specific threat attached to Muslims, and to a large degree also to the overlapping group of people with a Turkish background, when it comes to entering positions in the public and political sector, positions that are related to the shaping and maintenance of societal values. For the other groups, the estimated threat differs only slightly from the values predicted by a mere competition (ISEI score) and non-zero-sum (perceived shortage) argument.Footnote10

Conclusions and discussion

Western societies have become increasingly diverse, and demographic processes will reinforce this in the years ahead. Richard Alba has rightly argued that in many countries the age structure of the workforce will offer the descendants of formerly socioeconomically disadvantaged immigrants unique opportunities for social mobility and thus for effective structural integration. As research on ethnic inequality has shown, this view is strongly supported by the increasing success of immigrant children in education systems and labour markets in many countries. But acceptance and recognition are also necessary components of sustainable societal integration, and it is less clear how the members of the previous mainstream or dominant society will perceive and deal with these processes.

Richard Alba’s view is also quite optimistic in this regard. He has emphasised that the game is basically a non-zero-sum game and that, given the demographic structure, the intergenerational gains of the immigrant groups are not necessarily at the expense of the former mainstream. Thus, there should be no serious reason for a threat perception as would be expected under traditional theories of ethnic competition. Our analysis in the German context provides some support for this argument: in our vignette study, we presented twelve different occupations and demonstrated that dislike of immigrant minorities varied across these occupations. In an attempt to explain the patterns of aversion and non-aversion by key characteristics, the perceived shortage in the occupation, which is related to the non-zero-sum argument, performs much better than the status of the occupation, which would indicate competition.

Nevertheless, attitudes of rejection against immigrant groups, especially against Muslims, persist controlling for the demand of different jobs. And in the vignette analyses perceived shortage does a much poorer job in explaining the aversion regarding occupations that are in the public and political sector and are thus involved in the shaping and maintenance of societal norms and values. And this holds, again, especially for Muslims. We argue that a refined version of our concept of outgroup mobility threat (OMT) can contribute to understanding this. OMT captures the specific fear of being overtaken by intergenerational integration successes. In this general formulation, this seems challenged by and in conflict with the non-zero-sum argument. However, it is helpful to explicitly make the meanwhile common distinction between realistic and symbolic threat. More precisely, we have argued that the non-zero-sum argument is plausible for realistic threat, but that the logic is likely to be different for symbolic kinds of threat. If immigrant minorities enter occupations that shape societal norms and rules, and thus the value of the resources that the so-far mainstream members possess, it is not a non-zero-sum game anymore. OMT and the non-zero-sum argument are thus necessary corrections to each other, and the seemingly conflicting perspectives can be integrated via this differentiation.

But given this differentiation, the long-term consequences for societal integration are less straight-forward. New assimilation theory is based on the idea that in immigration countries more and more people from different backgrounds form a continuously changing mainstream, and ethno-racial distinctions will lose their influence on crucial aspects of life over time (Alba and Nee Citation1997, 863; Alba and Foner Citation2015), driven by strong general mechanisms, supported by structural forces such as the demographic ones. Many assimilation and integration theories speak out to these blurring boundaries (Wimmer Citation2008; Lamont and Molnár Citation2002) and without doubt there is much empirical evidence for this in the U.S. and many other immigration contexts (Alba Citation2005; Drouhot and Nee Citation2019).

However, post-colonial theory and critical race theory point to the continuity of othering based on perceptions of racial inferiority and white supremacy even though racialized people ascend into the mainstream (Embrick and Moore Citation2020; Paré Citation2022). Theories of ambivalence (Bauman Citation2016), hybridisation (Bhabha Citation2000; Spivak Citation1990), and orientalism (Said Citation1978) are less optimistic about long-term recognition of minorities suggesting that it could be precisely the blurring of boundaries that leads to irritation and anxiety on the part of the white majority, because the blurring boundaries dissolve the idea of whiteness as purity and the Western world as more civilised. Questioning established positions and privileges (Craig and Richeson Citation2014; Craig, Rucker, and Richeson Citation2018; Davis and Wilson Citation2021) and addressing structural racism (Bailey et al. Citation2017; Bonilla-Silva Citation2021) is rather leading to polarised debates about culture wars and cancel culture (Norris Citation2023) than to a new relaxed hybrid mainstream. Philosophical approaches explain the reluctance toward blurring boundaries and an ever more diverse mainstream through the comfort we find in the binary logic in which we as humans are trained to position ourselves towards ‘the other’ (Buber Citation1995).

The possible explanation for the persistence of non-recognition that we have analyzed in this paper is based on a different and clearer mechanism, but touches on some of these elements. In contemporary Germany, as in most other European countries, ‘Muslim/Islam’ is the brightest boundary, which is confirmed by our results. As a ‘religious’ marker, the external attribution contains not only generalisations and stereotypes about socioeconomic background, relevant skills and resources, or cultural habits, but also about basic norms and values that are perceived as different from those of the largely secular mainstream. Many people feel that these norms and values are at odds with the general rules of how society works or should work. This leads to a particular danger of an ‘either/or’ struggle over the constitution of society, rather than gradual learning and adaptation. And at the same time, it is precisely this struggle that makes the boundary brighter.

It is an open empirical question whether OMT posed by Muslims in value-shaping occupations will nevertheless decline, albeit perhaps with a slower gradient, if the perceived shortages in theses occupations continue to increase. above gives the impression that this is not the case, but the design and data do not allow us to do analyse this in more detail; one would need a much larger number of occupations and greater variance in their shortages to say this with greater certainty.

Richard Alba has already pointed to the fact that ethno-racial differences in access to positions and resources will not disappear completely, but he takes a fundamentally optimistic stance, betting on learning and adapting to diversity and counting on strong demographic structural forces. Although much points in this direction, the continued opposition of a significant portion of the mainstream to immigration and certain ethno-racial groups remains puzzling, and the rise of anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim political parties poses a challenge to the idea of directional progress. Consequently, Western immigration societies also face increasing cultural, ethnic, religious, and racial self-emphasis that contradicts the notion that ethnic boundaries automatically fade out if structural integration succeeds. In Germany and elsewhere in Europe, pronounced identity politics is also a signature of the current time, particularly because, despite all the intergenerational progress, the promises of equity and equality – including recognition – have yet to be convincingly realised (Foroutan Citation2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank Steffen Shah for his extremely dedicated help and work in the development of the vignette items and in the setup of the survey. We thank Nina Bühler and Caroline Simpson for their excellent support in preparing the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data of this study will be made available for scientific use via the DeZIM Research Data Center (https://fdz.dezim-institut.de/en). Estimated date of publication is the end of 2023.

Notes

1 Precise data from the official statistics is not available as the information on religious affiliation is not included in the German Microcensus.

2 The category was included in the survey for other purposes, but it makes no sense to include it in the analyses here. The formulation of the vignette referring to Germans without migration background triggers an anti-diversity framing of the question and a ‘bad’ or ‘very bad’ answer probably represents a pro-diversity attitude rather than a feared threat by this group.

3 We refer to this again in footnote 6.

4 The occupations were coded according to the classification scheme for the German Microcensus suggested by GESIS (https://www.gesis.org/missy/files/documents/MZ/isco_isei.pdf).

5 Weighting the vignettes with the redressment weight that is contained in the data set only marginally increases this share from (8.0 to 8.3). As in this paper we are interested in differences between minority groups and occupations and not in characteristics of the respondents, we do not use the redressment weight throughout the analyses.

6 Here, it is important to emphasize once again that the results would remain unchanged even if we excluded those 736 cases where the respondent belongs to the minority group which is specified in the formulation (see 'Data and methods'). More precisely, the percentages would not deviate by more that 0.1% in each case. Therefore, the racial hierarchy depicted in is not influenced by the actual number of individuals from each group in the sample.

7 For the group ‘Turkish’ this holds on a 1%-level, for all other groups even on a 0.1%-level.

8 Most, but not all people with a Turkish background in Germany are Muslim and among Muslims those with a Turkish background constitute the largest subgroup, so there is a large but not perfect overlap between these two categories.

9 We also tested whether the two dummies (Muslim or Turkish) interact with the perceived shortage or with the ISEI of the occupations, but this is not the case (on a level of at least p < .05).

10 This holds true even more if one takes out the category ‘Sinti and Roma’, a group that has also been related to symbolic threat mechanisms in Germany (Jedinger and Eisentraut Citation2020), from the group ‘other’. Then, only in the occupation local politicians would there be a small significantly higher OMT as predicted by ISEI score and perceived shortage.

References

- Alba, Richard. 2005. “Bright vs. Blurred Boundaries: Second-Generation Assimilation and Exclusion in France, Germany, and the United States.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 28 (1): 20–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141987042000280003.

- Alba, Richard. 2020. The Great Demographic Illusion: Majority, Minority, and the Expanding American Mainstream. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Alba, Richard, and Nancy Foner. 2015. Strangers No More. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Alba, Richard, and Christopher Maggio. 2022. “Demographic Change and Assimilation in the Early 21st-Century United States.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119 (13): e2118678119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2118678119.

- Alba, Richard, and Victor Nee. 1997. “Rethinking Assimilation Theory for a New Era of Immigration.” International Migration Review 31 (4): 826–874. https://doi.org/10.1177/019791839703100403.

- Alba, Richard, and Victor Nee. 2003. Remaking the American Mainstream. Assimilation and Contemporary Immigration. Cambridge/London: Harvard University Press.

- Attia, Iman. 2014. “Partizipation Durch Identitätspolitik. Selbstorganisation von Migrant*Innen in Einer Einwanderungsgesellschaft Wider Willen.” In Migration, Asyl und (Post-)Migrantische Lebenswelten in Deutschland. Bestandsaufnahme und Perspektiven Migrationspolitischer Praktiken, edited by Miriam Aced, Tamer Düzyol, Arif Rüzgar, and Christian Schaft, 311–336. Berlin: Lit Verlag.

- Bailey, Zinzi, Nancy Krieger, Madina Agénor, Jasmine Graves, Natalia Linos, and Mary T. Bassett. 2017. “Structural Racism and Health Inequities in the USA: Evidence and Interventions.” The Lancet 389 (10077): 1453–1463. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X.

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2016. Moderne und Ambivalenz. Das Ende der Eindeutigkeit. Hamburg: Hamburger Editionen.

- Baumann, Anne-Luise, Valentin Feneberg, Lara Kronenbitter, Saboura Naqshband, Magdalena Nowicka, and Anne-Kathrin Will. 2019. Ein Zeitfenster für Vielfalt: Chancen für die Interkulturelle Öffnung der Verwaltung. Bonn: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

- Bell, David A., Marko Valenta, and Zan Strabac. 2021. “A Comparative Analysis of Changes in Anti-Immigrant and Anti-Muslim Attitudes in Europe: 1990–2017.” Comparative Migration Studies 9 (1): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-021-00266-w.

- Bertelsmann Stiftung. 2015. Religionsmonitor. Verstehen was Verbindet. Sonderauswertung Islam 2015. Die Wichtigsten Ergebnisse im Überblick. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung.

- Bhabha, Homi K. 2000. Die Verortung der Kultur. Tübingen: Stauffenburg.

- BIK. 2021. Repräsentative Telefonbefragung im Rahmen des Nationalen Diskriminierungs- und Rassismusmonitors (NaDiRa-001-CATI). Methodenbericht. Hamburg: BIK Aschpurwis + Behrens.

- Billiet, Jaak, Bart Meuleman, and Hans De Witte. 2014. “The Relationship Between Ethnic Threat and Economic Insecurity in Times of Economic Crisis: Analysis of European Social Survey Data.” Migration Studies 2 (2): 135–161. https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnu023.

- Blalock, Hubert M. 1967. “Status Inconsistency, Social Mobility, Status Integration and Structural Effects.” American Sociological Review 32 (5): 790–801. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092026.

- Blumer, Herbert. 1958. “Race Prejudice as a Sense of Group Position.” The Pacific Sociological Review 1 (1): 3–7. https://doi.org/10.2307/1388607.

- BMI/BAMF – Bundesministerium des Innern/Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge. 2022. Migrationsbericht des Bundesamtes für Migration und Flüchtlinge im Auftrag der Bundesregierung. Migrationsbericht 2021. Berlin/Nürnberg: BMI/BAMF.

- Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. 2021. “What Makes Systemic Racism Systemic?” Sociological Inquiry 91 (3): 513–533. https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12420.

- Brubaker, Rogers. 2002. “Ethnicity Without Groups.” European Journal of Sociology 43 (2): 163–189. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003975602001066.

- Buber, Martin. 1995. Ich und Du. Ditzingen: Philipp Reclam jun. Verlag.

- Bundesregierung. 2017. Nationaler Aktionsplan Gegen Rassismus. Positionen und Maßnahmen zum Umgang mit Ideologien der Ungleichwertigkeit und den Darauf Bezogenen Diskriminierungen. Berlin: Bundesministerium des Innern, für Bau und Heimat; Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend. Bundesregierung.

- Campbell, Donald T. 1965. “Ethnocentric and Other Altruistic Motives.” In Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, edited by David Levine, 283–311. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Canan, Coşkun, and Naika Foroutan. 2016. “Changing Perceptions? Effects of Multiple Social Categorisation on German Population’s Perception of Muslims.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (12): 1905–1924. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1164591.

- Chung, Heejung, and Steffen Mau. 2014. “Subjective Insecurity and the Role of Institutions.” Journal of European Social Policy 24 (4): 303–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928714538214.

- Craig, Maureen A., and Jennifer A. Richeson. 2014. “On the Precipice of a “Majority-Minority” America.” Psychological Science 25 (6): 1189–1197. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614527113.

- Craig, Maureen A., Julian M. Rucker, and Jennifer A. Richeson. 2018. “The Pitfalls and Promise of Increasing Racial Diversity: Threat, Contact, and Race Relations in the 21st Century.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 27 (3): 188–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417727860.

- Czaika, Mathias, and Armando Di Lillo. 2018. “The Geography of Anti-Immigrant Attitudes Across Europe, 2002–2014.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (15): 2453–2479. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1427564.

- Davidov, Eldad, Daniel Seddig, Anastasia Gorodzeisky, Rebeca Raijman, Peter Schmidt, and Moshe Semyonov. 2020. “Direct and Indirect Predictors of Opposition to Immigration in Europe: Individual Values, Cultural Values, and Symbolic Threat.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (3): 553–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1550152.

- Davis, Darren W., and David C. Wilson. 2021. Racial Resentment in the Political Mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Decker, Oliver, Johannes Kiess, Ayline Heller, and Elmar Brähler. 2022. “Autoritäre Dynamiken in Unsicheren Zeiten.” In Neue Herausforderungen – Alte Reaktionen. Leipziger Autoritarismus Studie 2022. Gießen: Psychosozial Verlag.

- Dennison, James, and Lenka Dražanová. 2018. Public Attitudes on Migration: Rethinking How People Perceive Migration: An Analysis of Existing Opinion Polls in the Euro-Mediterranean Region. Florence: Migration Policy Centre, European University Institute.

- Deutsches Zentrum für Integrations- und Migrationsforschung (DeZIM). 2022. Rassistische Realitäten: Wie setzt sich Deutschland mit Rassismus auseinander? Auftaktstudie zum Nationalen Diskriminierungs- und Rassismusmonitor (NaDiRa). Berlin: DeZIM-Institut.

- De Vroome, Thomas, Borja Martinovic, and Maykel Verkuyten. 2014. “The Integration Paradox: Level of Education and Immigrants’ Attitudes Towards Natives and the Host Society.” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 20 (2): 166–175. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034946.

- Dixon, John, Kevin Durrheim, Colin Tredoux, Linda Tropp, Beverley Clack, and Liberty Eaton. 2010. “A Paradox of Integration? Interracial Contact, Prejudice Reduction, and Perceptions of Racial Discrimination.” Journal of Social Issues 66 (2): 401–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2010.01652.x.

- Dollmann, Jörg. 2017. “Positive Choices for All? SES- and Gender-Specific Premia of Immigrants at Educational Transitions.” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 49: 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2017.03.001.

- Dotson, Kristie. 2018. “On the Way to Decolonization in a Settler Colony: Re-Introducing Black Feminist Identity Politics.” AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 14 (3): 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180118783301.

- Drouhot, Lucas G., and Victor Nee. 2019. “Assimilation and the Second Generation in Europe and America: Blending and Segregating Social Dynamics Between Immigrants and Natives.” Annual Review of Sociology 45: 177–199. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073117-041335.

- El-Mafaalani, Aladin. 2018. Das Integrationsparadox. Warum Gelungene Integration zu Mehr Konflikten Führt. Köln: Kiepenheuer & Witsch.

- Embrick, David G., and Wendy L. Moore. 2020. “White Space(s) and the Reproduction of White Supremacy.” American Behavioral Scientist 64 (14): 1935–1945. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764220975053.

- Foroutan, Naika. 2012. “Innerdeutsche Grenze Islam? Desintegrative Folgen der Integrationsdebatte.” In Asiatische Deutsche, Vietnamesische Diaspora and Beyond, edited by Kien Nghi Ha, 321–335. Berlin/Hamburg: Verlag Assoziation.

- Foroutan, Naika. 2019. Die Postmigrantische Gesellschaft: Ein Versprechen der Pluralen Demokratie. Bielefeld: transcript.

- Foroutan, Naika, and Frank Kalter. 2021. “Race for Second Place? Explaining East-West Differences in Anti-Muslim Sentiment in Germany.” Frontiers in Sociology 6: 735421. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2021.735421.

- Foroutan, Naika, and Frank Kalter. 2022. “Integration.” In Begriffe der Gegenwart. Ein Kulturwissenschaftliches Glossar, edited by Brigitta Schmidt-Lauber, and Manuel Liebig, 153–162. Bonn: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung.

- Foroutan, Naika, Frank Kalter, Coşkun Canan, and Mara Simon. 2019. Ost-Migrantische Analogien I. Konkurrenz um Anerkennung. Unter Mitarbeit von Daniel Kubiak und Sabrina Zajak. Berlin: DeZIM-Institut.

- Ganzeboom, Harry B.G., Paul De Graaf, and Donald J. Treiman. 1992. “A Standard International Socio-Economic Index of Occupational Status.” Social Science Research 21 (1): 1–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/0049-089X(92)90017-B.

- Gordon, Milton M. 1964. Assimilation in American Life. The Role of Race, Religion, and National Origin. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gorodzeisky, Anastasia, and Moshe Semyonov. 2019. “Unwelcome Immigrants: Sources of Opposition to Different Immigrant Groups Among Europeans.” Frontiers in Sociology 4: 24. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2019.00024.

- Häder, Michael, and Sabine Häder. 2014. “Stichprobenziehung in der Quantitativen Sozialforschung.” In In Handbuch der Methoden der Empirischen Sozialforschung, edited by Nina Baur, and Jörg Blasius, 283–289. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Heath, Anthony Francis, and Yaël Brinbaum. 2014. Unequal Attainments: Ethnic Educational Inequalities in Ten Western Countries, 196. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Heath, Anthony, and Sin Yi Cheung. 2007. Unequal Chances: Ethnic Minorities in Western Labour Markets. London: British Academy.

- Hochschild, Arlie Russell. 2017. Fremd in Ihrem Land: Eine Reise ins Herz der Amerikanischen Rechten. Frankfurt a. M.: Campus.

- Honneth, Axel, and Ferdinand Sutterlüty. 2011. “Normative Paradoxien der Gegenwart – Eine Forschungsperspektive.” WestEnd Neue Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung 8 (1): 67–85.

- Hughes, Melanie M. 2016. “Electoral Systems and the Legislative Representation of Muslim Ethnic Minority Women in the West, 2000–2010.” Parliamentary Affairs 69 (3): 548–568. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsv062.

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Pippa Norris. 2016. “Trump, Brexit, and the Rise of Populism: Economic Have-Nots and Cultural Backlash” HKS Working Paper No. RWP16-026. Cambridge: Harvard JFK School of Government.

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Pippa Norris. 2017. “Trump and the Populist Authoritarian Parties: The Silent Revolution in Reverse.” Perspectives on Politics 15 (2): 443–454. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592717000111.

- Jackson, Michelle, Jan O. Jonsson, and Frida Rudolphi. 2012. “Ethnic Inequality in Choice-Driven Education Systems.” Sociology of Education 85 (2): 158–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040711427311.

- Jedinger, Alexander, and Marcus Eisentraut. 2020. “Exploring the Differential Effects of Perceived Threat on Attitudes Toward Ethnic Minority Groups in Germany.” Frontiers in Psychology 10: 2895. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02895.

- Kalter, Frank. 2022. “Integration in Migration Societies.” In Handbook of Sociological Science, Contributions to Rigorous Sociology, edited by Klarita Gërxhani, Nande Graaf, and Werner Raub, 135–153. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Kalter, Frank, and Nadia Granato. 2002. “Demographic Change, Educational Expansion, and Structural Assimilation of Immigrants: The Case of Germany.” European Sociological Review 18 (2): 199–216. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/18.2.199.

- Kalter, Frank, and Anthony Heath. 2018. “Dealing with Diverse Diversities. Defining and Comparing Minority Groups.” In Growing Up in Diverse Societies. The Integration of the Children of Immigrants in England, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden, edited by Frank Kalter, Jan O. Jonsson, Frank van Tubergen, and Anthony Health, 62–82. Oxford: Oxford University.

- Kalter, Frank, Jan O. Jonsson, Frank van Tubergen, and Anthony Heath. 2018. Growing Up in Diverse Societies. The Integration of the Children of Immigrants in England, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kao, Grace, and Marta Tienda. 2012. “Optimism and Achievement: The Educational Performance of Immigrant Youth.” In The New Immigrants and American Schools Interdisciplinary Perspectives on the New Immigration, edited by Marcelo M. Suárez-Orozco, Carola Suárez-Orozco, and Desirée Qin-Hilliard, 345–358. New York: Routledge.

- Kaschuba, Wolfgang. 2016. “Wahlverwandtschaften? Alte Zugehörigkeiten und Neue Zuordnungen in Europa.” In In Identitäten im Prozess. Region, Nation, Staat, Individuum Edited by Anna Margaretha Horatschek and Anja Pistor-Hatam, 137–149. Hamburg: De Gruyter.

- Khalil, Samir, Almuth Lietz, and Sabrina J. Mayer. 2020. Systemrelevant und Prekär Beschäftigt: Wie Migrant*Innen Unser Gemeinwesen Aufrechterhalten. DeZIM Research Notes – RN-2020-05. Berlin: Deutsches Zentrum für Integrations- und Migrationsforschung (DeZIM).

- Korteweg, Anna C., and Gökçe Yurdakul. 2014. The Headscarf Debates: Conflicts of National Belonging. Redwood City: Stanford University Press.

- Kuntz, Anabel, Eldad Davidov, and Moshe Semyonov. 2017. “The Dynamic Relations Between Economic Conditions and Anti-Immigrant Sentiment: A Natural Experiment in Times of the European Economic Crisis.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 58 (5): 392–415. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020715217690434.

- Küpper, Beate, Daniela Krause, and Andreas Zick. 2019. “Rechtsextreme Einstellungen in Deutschland 2002–2018/19.” In Verlorene Mitte – Feindselige Zustände. Rechtsextreme Einstellungen in Deutschland 2018/19 Edited by Andreas Zick, Beate Küpper, and Wilhelm Berghan, 117–146. Dietz: Bonn.

- Lamont, Michèle. 2018. “Addressing Recognition Gaps: Destigmatization and the Reduction of Inequality.” American Sociological Review 83 (3): 419–444. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122418773775.

- Lamont, Michèle, and Virág Molnár. 2002. “The Study of Boundaries in the Social Sciences.” Annual Review of Sociology 28 (1): 167–195. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.28.110601.141107.

- Lengfeld, Holger, and Jessica Ordemann. 2017. “Der Fall der Abstiegsangst, Oder: Die Mittlere Mittelschicht als Sensibles Zentrum der Gesellschaft. Eine Trendanalyse 1984–2014.” Zeitschrift für Soziologie 46 (3): 167–184. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-2017-1010.

- Lindenberg, Siegwart. 1989. “Social Production Functions, Deficits, and Social Revolutions.” Rationality and Society 1 (1): 51–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043463189001001005.

- Meuleman, Bart, Eldad Davidov, and Jaak Billiet. 2018. “Modeling Multiple-Country Repeated Cross-Sections: A Societal Growth Curve Model for Studying the Effect of the Economic Crisis on Perceived Ethnic Threat.” Methods, Data, Analyses: A Journal for Quantitative Methods and Survey Methodology (mda) 12 (2): 185–209.

- Mudde, Cas. 2021. “Populism in Europe: An Illiberal Democratic Response to Undemocratic Liberalism (The Government and Opposition Leonard Schapiro Lecture 2019).” Government and Opposition 56 (4): 577–597. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2021.15.

- Nee, Victor, and Richard Alba. 2013. “Assimilation as Rational Action in Contexts Defined by Institutions and Boundaries.” In The Handbook of Rational Choice Social Research, edited by Rafael Wittek, Tom A.B. Snijders, and Victor Nee, 355–381. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Norris, Pippa. 2023. “Cancel Culture: Myth or Reality?.” Political Studies 71 (1): 145–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/00323217211037023.

- Olgun, Ufuk. 2015. “Does Islam Belong to Germany? On the Political Situation of Islam in Germany.” In The State as an Actor in Religion Policy. Policy Cycle and Governance Perspectives on Institutionalized Religion Edited by Maria Grazia Martino, 71–84. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Paré, Céline. 2022. “Selective Solidarity? Racialized Othering in European Migration Politics.” Amsterdam Review of European Affairs 1 (1): 42–61.

- Park, Robert Ezra. 1950. Race and Culture. Glencoe: The Free Press.

- Pew Research Center. 2017. Europe’s Growing Muslim Population. Washington: Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2017/11/FULL-REPORT-FOR-WEB-POSTING.pdf

- Pfündel, Katrin, Anja Stichs, and Kerstin Tanis. 2021. Muslimisches Leben in Deutschland 2020 - Studie im Auftrag der Deutschen Islam Konferenz. Forschungsbericht 38 des Forschungszentrums des Bundesamtes. Nürnberg: BAMF.

- Said, Edward W. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Salikutluk, Zerrin. 2016. “Why Do Immigrant Students Aim High? Explaining the Aspiration–Achievement Paradox of Immigrants in Germany.” European Sociological Review 32 (5): 581–592. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcw004.

- Schaeffer, Merlin. 2014. Ethnic Diversity and Social Cohesion: ImmiGration, Ethnic Fractionalization and Potentials for Civic Action. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Schönwälder, Karen, Cihan Sinanoğlu, and Daniel Volkert. 2013. “The New Immigrant Elite in German Local Politics.” European Political Science 12: 479–489. https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2013.17.

- Schührer, Susanne. 2018. Türkeistämmige Personen in Deutschland. Erkenntnisse aus der Repräsentivuntersuchung ,Ausgewählte Migrantentgruppen in Deutschland 2015 (RAM)‘. Working Paper 81. Nürnberg: BAMF Forschungszentrum.

- Sherif, Muzafer, and Carolyn W. Sherif. 1969. Social Psychology. New York: Harper & Row.

- Spivak, Gayatry Chakravorty. 1990. The Post-Colonial Critic. Interviews, Strategies, Dialogues. New York/London: Routledge.

- Stephan, Walter G., and Cookie W. Stephan. 2000. “An Integrated Threat Theory of Prejudice.” In In Reducing Prejudice and Discrimination, edited by Stuart Oskamp, 23–45. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Stephan, Walter G., and Cookie W. Stephan. 2017. “Intergroup Threat Theory.” In The International Encyclopedia of Intercultural Communication, edited by Kim Y. Yung, 1–12. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118783665.ieicc0162

- Stephan, Walter G., Oscar Ybarra, and Kimberly R. Morrison. 2009. “Intergroup Threat Theory.” In In Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination, edited by Todd D. Nelson, 43–60. New York: Psychology Press.

- Štětka, Václav, Sabina Mihelj, and Fanni Tóth. 2021. “The Impact of News Consumption on Anti-Immigration Attitudes and Populist Party Support in a Changing Media Ecology.” Political Communication 38 (2): 539–560.

- Suda, Kimiko;, Sabrina J. Mayer, and Christoph G. Nguyen. 2020. “Antiasiatischer Rassismus in Deutschland.” in: APuZ (Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte), 42–44, S. 39–44. (https://www.bpb.de/apuz/antirassismus-2020/316771/antiasiatischer-rassismus-in-deutschland

- Sutterlüty, Ferdinand. 2010. In Sippenhaft. Negative Klassifikationen in Ethnischen Konflikten. Frankfurt a. M.: Campus Verlag.

- Ten Teije, Irene, Marcel Coenders, and Maykel Verkuyten. 2013. “The Paradox of Integration.” Social Psychology 44 (4): 278–288. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000113.

- Thomas, Elaine R. 2011. Immigration, Islam, and the Politics of Belonging in France: A Comparative Framework. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Tolsma, Jochem, Marcel Lubbers, and Mérove Gijsberts. 2012. “Education and Cultural Integration among Ethnic Minorities and Natives in The Netherlands: A Test of the Integration Paradox.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 38 (5): 793–813. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2012.667994.

- Uenal, Fatih. 2016. “Disentangling Islamophobia: The Differential Effects of Symbolic, Realistic, and Terroristic Threat Perceptions as Mediators Between Social Dominance Orientation and Islamophobia.” Journal of Social and Political Psychology 4 (1): 66–90. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v4i1.463.

- Verkuyten, Maykel. 2016. “The Integration Paradox.” American Behavioral Scientist 60 (5-6): 583–596. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764216632838.

- Waters, Mary C., and Marisa Gerstein Pineau. 2015. The Integration of Immigrants Into American Society. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- White, Michael J., and Jennifer E. Glick. 2009. Achieving Anew: How New Immigrants Do in American Schools, Jobs, and Neighborhoods. New York: Russell Sage.

- Wimmer, Andreas. 2008. “The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: A Multilevel Process Theory.” American Journal of Sociology 113 (4): 970–1022. https://doi.org/10.1086/522803.

- Wüst, Andreas, and Henning Bergmann. 2023. “Repräsentation von Menschen mit Einwanderungsgeschichte in deutschen Parlamenten.” MDI-Expertise https://mediendienst-integration.de/fileadmin/Dateien/MDI_Expertise_Politische_Repraesentation.pdf.

- Zick, Andreas, and Nora Rebekka Krott. 2021. Einstellungen zur Integration in der Deutschen Bevölkerung von 2014 bis 2020. Universität Bielefeld: IKG – Institut für Interdisziplinäre Konflikt- und Gewaltforschung.

Appendix

Table A1. Linear probability models of OMT on vignette factors and occupational characteristics.