ABSTRACT

Across Europe, citizenship is traditionally attributed at birth through descent only. As immigrant populations grow, policy-makers have come under pressure to extend citizenship rights to the children of immigrants born in the country. While such inclusive measures often counter political opposition, public attitudes on this question remain remarkably underexplored. In this study, we report on the results of an original choice-based conjoint survey experiment designed to examine which parental attributes affect respondents’ willingness to grant citizenship to newborns. We implement the survey experiment in Italy, where over one million children do not have Italian citizenship, yet reform proposals have so far been unsuccessful. In line with our pre-registered expectations, we find that respondents are more likely to support birthright citizenship for children born to parents who are economically, legally and socially integrated in society. These attitudes vary little by political background, education and age-category of respondents. Our findings suggest that incorporating immigration-related conditionality in birthright citizenship proposals is key to convincing sceptical publics of the legitimacy of such measures.

Introduction

In many European countries citizenship is inherited through lineage, via the principle of ius sanguinis, as opposed to being granted based on birth in the territory of a state, via the principle of ius soli (Vink and Bauböck Citation2013). Children born to immigrant parents must typically meet specific requirements to register as citizens when they turn 18.

Proposals to introduce or expand territorial birthright citizenship for children born to immigrant parents have become the object of intense political debate in many European countries, from Germany to Greece and Italy (Tintori Citation2018). Social and political movements have called, sometimes successfully, for legal changes ensuring citizenship to the increasingly large population of children who currently grow up without the citizenship status of the country they were born in. Populist right-wing political parties, such as Germany’s Alternative for Germany or Italy’s Lega, have made these issues core tenets of their electoral campaigns and positions (Dekeyser Citation2017).

The outcomes of public debates on birthright citizenship have important societal implications. Governments must decide not only whether to introduce territorial birthright citizenship, but also what criteria to restrict it by. Although Germany, Portugal, Belgium, Ireland and the UK all adopted conditional ius soli legislation, their requirements differ extensively. These are consequential decisions because research shows that the acquisition of citizenship during childhood has positive implications for individual life chances. Labussière, Levels, and Vink (Citation2021) for the Netherlands, and Felfe et al. (Citation2021) for Germany find that children with citizenship have better educational trajectories than those without. In contrast, children without citizenship are at higher risk of dropping out of school. At the societal level, Felfe et al. (Citation2020) find that birthright citizenship increases the likelihood of cooperation between children of immigrant and native origin. Avitabile, Clots-Figueras, and Masella (Citation2013) show that eligibility for birthright citizenship may also have positive outcomes for parents. They find for Germany that parents whose children are eligible for citizenship are more likely to use the national language and to interact with the local community.

Opposition to proposed reforms rests on the assumption of resistance by the electorate. Yet, despite the societal relevance and political salience of these contested reforms, the attitudes of the general population on the question of ius soli for immigrants’ children have remained largely unexplored. Current political science literature has focused on attitudes towards immigrants (Hainmueller and Hopkins Citation2015), on preferences for naturalisation criteria (Donnaloja Citation2022), dual citizenship (Vink, Schmeets, and Mennes Citation2019) and immigrant voting rights (Rosenberg and Wejryd Citation2022). We build on this strand of research by investigating how out-group dynamics shape attitudes towards the legal inclusion at birth of children born in the country to immigrant parents. Following the findings from existing studies on the territorial admission and rights of immigrants, we hypothesise that public support for ius soli is conditional on attributes that signal economic, legal and social integration of the immigrant parents. We thus expect that broader exclusionary attitudes directed towards immigrant parents spill over to their children.

We investigate what drives support for, or opposition to, the granting of territorial birthright citizenship in Italy. Around one million children, either born in Italy or who arrived there as children, do not have Italian citizenship (ISTAT Citation2020). In order to become Italian citizens, they have to wait until they turn 18 and actively register within a year. In the last decade, attempts to change the law have failed due to strong right-wing political opposition and tepid left-wing support.

Using a choice-based conjoint experiment design we test whether different aspects of legal, economic and social integration of immigrant parents, as well as ascribed characteristics, affect respondents’ support for territorial birthright citizenship. We examine which of these aspects are most salient in the public’s view and to what extent preferences vary along respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics: age, educational attainment and voting behaviour. We find that respondents largely agree on the conditions under which ius soli citizenship becomes acceptable. Across all respondents, parents’ employment status, legal status and length of residence are the most relevant criteria for birthright citizenship entitlement. Manifestations of socio-cultural integration and ascribed characteristics affected right-wing voters’ likelihood of supporting ius soli, but to a significantly lesser extent.

We start by discussing the theory and evidence from the literature on attitudes toward immigrants to derive our hypotheses. We then outline our data and empirical strategy, followed by presenting the results of the conjoint experiment. We conclude with a discussion of our main findings and their implications.

Theorising attitudes to birthright citizenship

The public may or may not view ‘such arbitrary criteria’ as country of birth as a relevant criterion for inclusion (Shachar Citation2009). On the one hand, existing citizens may recognise those who were born in the country as equal stakeholders. Country of birth may also indicate current and future connection to the nation. On the other hand, natives may not deem birth sufficient for the full political inclusion provided by citizenship, especially in a country where citizenship has historically been administered entirely through the principle of descent-based birthright citizenship.

We expect the general public to value country of birth for the entitlement to citizenship at birth, but to do so conditionally. Any such conditionality will concern the child’ parents, rather than the child. The reason for this is that conditions for the entitlement to citizenship at birth necessarily depend -and in all European countries where such rules exist do so (Vink et al. Citation2021)- on ascribed characteristics of the child -deriving from the parents’ status and experience- and cannot be assessed based on the behaviour of the child at that point in time. Moreover, parents provide an indication of what the child is anticipated to be brought up to be. For this reason, we expect that public attitudes of exclusion towards the parents are likely to translate into a similar sentiment towards the parents’ offspring.

To derive theoretical expectations about the conditions under which public attitudes to birthright citizenship for immigrants’ children vary, we rely on two strands of literature that have approached attitudes to immigration broadly from two perspectives: first, social identity theory emphasises immigration as cultural threat; second, economic competition theory emphasises the perceived negative effects of immigration on material wellbeing. While not addressing the question of public acceptance of birthright citizenship directly -on which we were not able to identify any existing studies- these literature strands are relevant as we expect that attitudes to the political inclusion of native-born, but foreign-origin children are determined by attitudes to immigration more broadly.

When looking at the first strand of literature, derived from social identity theory, existing citizens are likely willing to accept as co-nationals those they recognise as part of their in-group (Tajfel and Turner Citation1979). People tend to have warmer attitudes towards the immigrants whose origins they perceive as culturally and ethnically more similar to theirs (Hainmueller and Hopkins Citation2015; Hainmueller and Hangartner Citation2013; Donnaloja Citation2022; Kobayashi et al. Citation2015). As country or region of origin may elicit prejudice due to several assumed characteristics associated with it, from ethnicity to skill-level and legal status, it is important to measure these characteristics separately from each other (Adida, Laitin, and Valfort Citation2010; Donnaloja Citation2022). Some studies on attitudes towards immigrants and naturalisation find evidence of a cultural and racial hierarchy (Ford Citation2011; Ostfeld Citation2017; Ramos, Pereira, and Vala Citation2020; Gang, Rivera-Batiz, and Yun Citation2013). Western Europeans also seem to prefer immigrants from other western as opposed to eastern European countries (Hellwig and Sinno Citation2017). For example, Sniderman et al.’s (Citation2000) research in Italy finds that Italians favour African to Eastern European immigrants. Country of origin may also signal differences in cultural practices which may lead to a perception of threat. Extensive evidence suggests that Europeans are hostile towards Muslims. This may be because they perceived Muslims to hold values and habits that are incompatible with the Christian way of life and to be a potential security threat (Hellwig and Sinno Citation2017; Donnaloja Citation2022; McLaren and Johnson Citation2007; Sobolewska, Galandini, and Lessard-Phillips Citation2017).

Based on this evidence we hypothesise that:

H1: Citizens are more likely to support territorial birthright citizenship for immigrants’ children if the newborn’s parents are ethno-culturally proximate to the majority population.

Participation in and adoption of the host country's culture may also signal socio-cultural integration. Cross-cultural psychology defines integration as one of four potential strategies of acculturation, which is the extent to which people who grew up in one cultural context adapt to a new culture (Berry Citation1997). In contrast to marginalisation and separation, integration and assimilation occur when there is participation in and adoption of the culture of the host country. Common indicators of socio-cultural integration are having friends, intermarriage and eating local foods (Sobolewska, Galandini, and Lessard-Phillips Citation2017; Ostfeld Citation2017). For example, Sobolewska, Galandini, and Lessard-Phillips’s (Citation2017) study on multidimensional integration finds that having friends from the host country is more important to people’s conceptions of integration than intermarriage.

Moreover, citizenship does not only grant rights, political equality and protection, but it also establishes a sense of national identity and belonging. Attachment to this group membership may lead people to expect loyalty, attachment and commitment to the group from fellow members. The perception of conflicting loyalties might drive current members to reject potential members. For example, debates around conflicting loyalties of athletes with dual citizenship often arise in the context of high-stakes sporting events, such as the World Cup and the Olympics, where people expect loyalty and commitment to one’s nation (Oonk Citation2021). Recently, the German midfielder of Turkish origins Mesut Ozil was criticised for singing the Turkish national anthem at a WorldCup game (Waas Citation2021). As Kostakopoulou and Schrauwen (Citation2014) note, these sport competitions have been entangled with narratives of national identity and allegiance. We therefore expect the following:

H2: Citizens are more likely to support territorial birthright citizenship for immigrants’ children if the newborn’s parents are more socially integrated.

A second strand of research has identified the perception or experience of economic contribution as determinants of people’s preferences for inclusion. Perceived or experienced economic threat may explain why citizens prefer immigrants who are highly skilled as opposed to low skilled and who are in employment as opposed to not. Research across country contexts has found that majority populations in western countries favour high-skilled as opposed to low-skilled immigrants both for entry into the country and for naturalisation (Dražanová Citation2022; Hainmueller and Hiscox Citation2010; Citrin et al. Citation1997; Donnaloja Citation2022; Hainmueller and Hangartner Citation2013; Harell et al. Citation2012; Kobayashi et al. Citation2015). People may perceive or experience low-skilled immigrants as competitors over public resources, e.g. the welfare state and taxes, as well as jobs (Kunovich Citation2013; Polavieja Citation2016). However, the uniform preference for the highly skilled suggests that socio-tropic considerations about the overall economic contribution of immigrants, rather than individual concerns, influence these attitudes (Ford and Mellon Citation2020). Research finds that attitudes are particularly negative towards those without an occupation. This may be because natives are less likely to consider immigrants as deserving of welfare provision, and they are worried about welfare magnetism (Wright and Reeskens Citation2013; Reeskens and van der Meer Citation2019). Language is also an indicator of socio-cultural and economic integration. Research on both citizenship preferences and on broader attitudes towards immigrants finds that respondents prefer immigrants who speak the native language well over those who do not (Donnaloja Citation2022; Hainmueller and Hopkins Citation2015; Chandler and Tsai Citation2001). Drawing on this literature, we expect that:

H3: Citizens are more likely to support territorial birthright citizenship for immigrants’ children if the newborn’s parents are socio-economically integrated.

In addition to drivers of openness towards immigrants, citizens may respond more positively to children whose parents meet additional conditions that signal legitimacy of stay. Studies have shown that attitudes are relatively more negative towards undocumented migrants (Espenshade and Calhoun Citation1993; Hainmueller and Hopkins Citation2015). This is likely due to assumptions around the low potential to integrate and to contribute economically associated with irregular migration (Blitz Citation2017). Unwanted irregular migration has also been at the centre of the Italian political debate (Urso Citation2018). However, studies for the USA are unclear on whether these negative attitudes extend to the children of undocumented immigrants or not (Davidson and Burson Citation2017; Park et al. Citation2011). Lawful residence is also typically a precondition for citizenship. Citizenship is the final step of a process of legal integration, which starts with having acquired permission from the state to enter and later settle on that territory (Whitaker and Doces Citation2021). If people view the birth of the child of undocumented immigrant parents on the territory as illegitimate, they are likely to see any subsequent form of legal integration as unwarranted. They may fear that parents use the birth of their child strategically in order to gain them entitlement to citizenship (Finotelli, La Barbera, and Echeverría Citation2018).

In contrast, a longer period of residence may indicate integration and commitment to settling for the long term (Donnaloja Citation2022). It may also assuage fears that parents strategise the birth of their child in order to gain them entitlement to citizenship (Finotelli, La Barbera, and Echeverría Citation2018). Most existing ius soli provisions in Europe are contingent on at least one parent’s legal status and length of stay (Vink et al. Citation2021). We therefore hypothesise that:

H4: Citizens are more likely to support territorial birthright citizenship for immigrants’ children if the newborn’s parents signal legitimacy of stay.

Media debates typically problematise immigrants by presenting them as part of a large phenomenon. In addition to individual immigrant characteristics, people may feel more threatened the higher they perceive the volume of claims to be (Sides and Citrin Citation2007). People may perceive numbers as a concern especially if they think immigrants will change the demographic, economic and cultural composition of the country for the worst (Alba, Rumbaut, and Marotz Citation2005). That is, people may be alarmed by the volume of immigration only for the groups of immigrants they are more hostile towards. Consistent with this, Jeannet, Heidland, and Ruhs (Citation2021) find that Europeans prefer refugee policies that impose limits on numbers of refugees allowed in. We therefore test the following hypothesis:

H5: Citizens are more likely to support territorial birthright citizenship for immigrants’ children if the newborn’s family size signals limited threat due to the volume of immigration.

Heterogeneous attitudes

Research has examined how variation in attitudes towards immigrants depends not only on the groups of immigrants who are the target of these attitudes, but also on the characteristics of the majority population that holds these attitudes. Natives of low socio-economic status, who are relatively older and who vote for right-wing parties are typically more averse to immigration and more prone to believe that immigration has negative economic and cultural effects. However, it is not clear why that is. Some studies suggest that the low-skilled are in a weaker economic position and therefore more vulnerable to competition over resources, including jobs (Mayda Citation2006; Scheve and Slaughter Citation2001). However, this explanation is not coherent with the fact that both low-skilled and high-skilled people are more likely to oppose low-skilled immigration (Hainmueller and Hiscox Citation2010). Alternatively, these groups may have more restrictive preferences because they are more concerned about the cultural and racial implications of immigration and because they are more attached to their national identity (Sniderman et al. Citation2000; McLaren and Johnson Citation2007; Dustmann and Preston Citation2007).

Beyond overall concerns about immigration, experimental studies have been able to investigate whether there is heterogeneity among respondents based on socio-economic status, age and political affiliation with respect to the type of immigrant who is preferred. Remarkably, these studies find very little variation (Hainmueller and Hopkins Citation2015; Donnaloja Citation2022; Sobolewska, Galandini, and Lessard-Phillips Citation2017; Whitaker and Doces Citation2021). Yet, in Italy, where the reform to include a ius soli principle in the citizenship law has been a salient political issue since 2017, we expect preferences to align with political partisanship. Given the importance of cultural and racial worries in shaping average attitudes we expect that average effects are driven by the groups most likely to be concerned about them, namely those who voted for a right-wing party in the last general elections. We expect supporters of the populist party Five Star Movement to be positioned somewhere in the middle. The party was ambiguous about its position on the issue, claiming it should be down to the electorate to vote on it. Party members abstained from voting on the motion when it was presented in the Senate at the end of 2017.

H6: Citizens who are right-wing party voters are more likely to support territorial birthright citizenship for immigrants’ children if the newborn’s parents are ethno-culturally proximate to the majority population; for left-wing party voters we expect that ethno-cultural attributes matter less or do not matter.

Empirical strategy

We test our hypotheses by employing a choice-based conjoint survey experiment design, whereby we presented respondents with fictitious profiles of children born to immigrant parents and had to express favouritism or lack thereof for each. Conjoint profiles are characterised by several attributes, which are randomised to allow to identify what drives differences in outcomes. This experimental design is ideal for investigating the drivers of multidimensional attitudes (Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto Citation2014). It is also less susceptible to social desirability bias than other survey designs as respondents are not asked directly about their attitudes (Horiuchi, Markovich, and Yamamoto Citation2022).

We commissioned the public opinion and data company YouGov to field the experiment through its online panel in December 2021. Our sample of 1521 respondents is weighted to be nationally representative in terms of gender, age, area of residence and education. Since we are interested in attitudes around the extension of citizenship, at the point of analysis we excluded respondents from the sample who are not Italian citizens for a total sample of 1463. We used Lukac and Stefanelli (Lukac and Stefanelli Citation2020)’s shiny app to do a-priori power analysis to estimate how many respondents we needed to have sufficient statistical power to carry out the intended analysis. Details of this are in the Supplementary Materials. The study received ethics clearance from the Ethics Committee at the authors’ institution (project code: 20211027). We pre-registered the study on the OpenScience Framework before data collection, including detailed hypotheses, design and analysis.

Following brief instructions, respondents were shown 10 profile conjoints in pairs to increase ecological validity (Hainmueller, Hangartner, and Yamamoto Citation2015). Hainmueller et al.’s research (Citation2015) shows that profiles shown in pairs aid decision-making because they give a direct comparison. Each conjoint profile included 11 attributes, each with several possible levels. Respondents were then asked to select for whom they are in favour of Italian citizenship at birth, with the option to support citizenship for only one, both or neither profile. We decided not to force respondents to choose between profiles in order to estimate their level of unconditional support for/opposition to ius soli. Moreover, as citizenship is not a finite and scarce resource, it can in principle be allocated to everyone. At the end of the conjoint exercise we collected socio-demographic information on the respondents.

Measures

- We operationalise ethno-cultural similarity as parents’ country of origin and religion. We choose countries of origin that have been the object of discussions in media and political debates (Urso Citation2018). The Chinese community is one of the largest immigrant groups in Italy and Chinese people have been the target of heightened abuse since the Covid-19 pandemic started in 2020 (Devakumar et al. Citation2020). Italians are also likely to be more averse to immigrants of origins associated with cultural practices deemed incompatible with Italian values, for example from a Muslim-dominant country such as Pakistan. Immigrants from African countries are often viewed as having entered the country without permission and may therefore be the target of greater hostility. Finally, people may be more likely to dislike eastern Europeans who tend to cluster in low-skilled and low-paid occupations. Conversely, we expect relatively more positive attitudes towards immigrants from Argentina. We choose this as a reference country against which to compare the others because it has historically been one of Italy’s most significant diaspora destinations. It received around three million Italians between the nineteenth and twentieth century (Rosoli Citation1994). To this day, the similarity in language and culture, including the Catholic religion, have translated into long-lasting close ties between the two countries. We therefore include the following countries of origin: China, Romania, Senegal, Pakistan, Argentina. We do not expect a country among Romania, Pakistan, China and Senegal to elicit more negative attitudes than the others and therefore choose Argentina as reference category. We measure religion in three categories, Muslim, Catholic and no religion. Muslims have been the main target of hostile sentiments in the West, including in Italy (Cervi, Tejedor, and Gracia Citation2021). Catholic indicates the country’s dominant religion, whereas no religion provides a neutral point of comparison.

- We measure social integration as the nationality of four best family friends and parents’ support in international sports events, such as the football WorldCup or the Olympic Games. In line with acculturation frameworks (Berry Citation1997), we distinguish between those who have no, some and all Italian family friends: all Italian; two Italian and two foreign; and between those who support the Italian team; both the Italian and country of origin team; the country of origin team.

- We operationalise socio-economic integration as Parents’ employment status, Parents’ educational attainment and Parents’ language fluency. We distinguish between mother’s and father’s employment status. This leads to four categories: both parents work, only mother works, only father works, neither parent works. We measure education in three levels: primary school diploma, secondary school diploma, university degree. We measure Italian language fluency in three levels: limited; sufficient for effective communication; excellent.

- We measure legitimacy of stay as parents’ legal status and parents’ length of stay. Legal status is measured as ‘permesso di soggiorno’, the documentation needed by non-EU citizens to lawfully reside in Italy and ‘senza permesso di soggiorno’ to indicate those without it. Since Romanians are not subject to this requirement to live in Italy, the attribute was not used in combination with Romania as country of origin. In Italy, the proposed ius soli reform was conditional on a five-year residency requirement. We therefore include options that are both below and above this threshold: 3 years, 5 years, 10 years, 15 years.

- Family size: we measure family size as one, two or four children.

To test H6 we used information collected by YouGov on how each respondent voted in the last general elections before the survey (2018). We recoded voting at the general elections of 2018 from nine to four categories: right-wing (including Lega, Forza Italia, Fratelli d’Italia), Fivestar movement and left-wing party (including Partitio Democratico, Piu’Europa, Liberi Uguali), other (including minor parties and those who abstained from voting). A summary of all attributes and of respondent characteristics can be found in Tables S1 S2 respectively. Table S2 also includes corresponding benchmark data for respondent characteristics taken from ISTAT, Eurostat and the Ministry of Interior.

Analytical strategy

We start by confirming the randomisation of attributes and check for balance of respondent characteristics. In the analysis we first calculate the proportion of profiles respondents consider favourably for citizenship (‘average acceptance rate’). We also calculate the proportion of respondents who accepted and who opposed all profiles presented to them. Second, we estimate the average marginal component effects (AMCEs) by employing a linear probability model, where the choice to be in favour or against citizenship is the outcome variable and the attributes are independent categorical variables (Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto Citation2014). The regression coefficient associated with each attribute level is an estimate of the AMCE, i.e. the effect of moving from the reference category to that level. As reference category for each attribute we choose the attribute level that we expected to lead to the least favourable outcome. This is with the exception of country of origin, for which we choose Argentina as reference category against which to compare the others to aid interpretation of results. To account for the randomisation restriction between country of origin and legal status we include an interaction term between the two attributes in the linear regression. To estimate the AMCEs of these two attributes we compute the linear combination of the appropriate coefficients in the interaction, weighted according to the probability of occurrence. In all the analyses we cluster standard errors by respondent and apply the weights provided by YouGov.

Third, to demonstrate that the preference patterns identified are not sensitive to the arbitrary choice of a reference category, we compute the marginal mean (MM), the marginal level of support, for each attribute level (Leeper, Hobolt, and Tilley Citation2020). To compare MMs of restricted attributes, we partition the sample in order to drop observations that included restricted attribute levels. Because ‘Romania’ was not allowed in combination with ‘undocumented legal status’, to compare the MM of ‘Romania’ and other countries we drop the profiles that included ‘undocumented’ as legal status.

Fourth and fifth, we investigate whether there is heterogeneity in preferences across respondents with respect to average acceptance rate and attribute level MMs.

Sixth, we explore interaction terms between attributes. Following Egami and Imai (Citation2019), we use the R package FindIt to estimate average marginal interaction effects (AMIE) on the probability of supporting birthright territorial citizenship. AMIE are not sensitive to differences in baseline values which is a typical issue when estimating interaction effects in conjoint experiments (Leeper, Hobolt, and Tilley Citation2020).

As robustness analysis we estimate alternative specifications. We first run the analysis including additional controls in the model for respondent characteristics to check that the findings are not driven by imbalance in sample characteristics. To account for the correlation of responses within each individual, we estimate a model incorporating fixed effects and another one incorporating random effects. To test carry-over assumptions we estimate whether AMCEs are stable across the five pairs of choice tasks (details on the design in the Supplementary materials).

Findings

We first look at the overall support for granting territorial birthright citizenship to immigrants’ children. Among all conjoint profiles, the average rate of acceptance is 59.5 per cent. This is relatively high given that a fraction of profiles, namely those of immigrants who have undocumented legal status, would not be eligible under the typical conditional ius soli provision. The average acceptance rate increases to 64 per cent if we restrict the sample to profiles with children born to documented migrant parents and decreases to 52.6 per cent among those with irregular migrant parents.

As much as 25 per cent (n = 362) of respondents were in favour of granting citizenship to children in all profiles presented to them, while 10 per cent (n = 142) were against territorial citizenship under any circumstances presented. The fact that those who opposed birthright citizenship in all profiles are overwhelmingly right-wing and that, in contrast, those who agreed in all profiles are mostly left-wing voters, suggests that these choices were intentional. The remaining 65 per cent of respondents support territorially-based birthright citizenship conditional on parental characteristics.

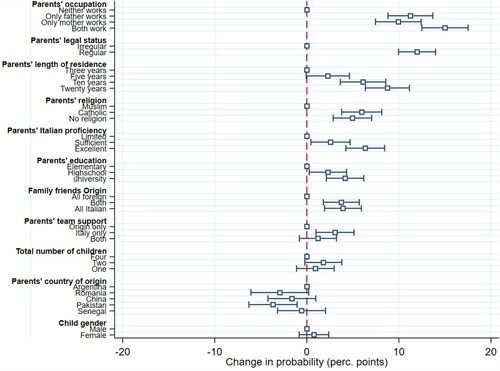

As shown in respondents are highly selective in their preferences, mostly in line with our expectations. All effects we comment on are statistically significant at the 5 per cent level of statistical significance (Table S4). In order of magnitude, the attributes that have most bearing on respondents’ choices are parents’ legal status, parents’ employment status and parents’ length of residence.

Figure 1. Attribute average marginal component effects on the probability of support for territorial birthright citizenship.

Note: OLS estimates of average effects of each randomised attribute of the probability of supporting birthright territorial citizenship with clustered standard errors and weights. Open squares show AMCE point estimates and the horizontal lines delineate 95% confidence intervals. Open squares without horizontal lines show reference categories.

Respondents are more likely to grant citizenship at birth to children whose parents have a legal right to stay as opposed to those who have not, by 12 percentage points. Both parents working, only the mother working, or only the father working increases the probability of the granting of citizenship by 15 percentage points, 9.9 percentage points and 11.2 percentage points, respectively. Strong preference for parents who reside legally in the country and who have been for long periods of time indicates that citizenship is viewed as a step that follows and, arguably, rewards legal integration. It is also possible that aversion towards undocumented migrants is due to fears of parents using the birth of their child to secure their own legal status. Existing citizens may be reluctant to granting a permanent, typically irreversible claim on belonging and rights in the country to immigrants whose stay is not lawful. In a related manner, fear of welfare dependency is the likely cause of the negative attitudes we find towards unemployed parents. Unemployed people are often the object of hostility, but more so if they are of immigrant origin (Reeskens and van der Meer Citation2019). With respect to citizenship it is possible that existing citizens fear that granting citizenship to a child entitles their parents to welfare benefits and claims. This finding is also consistent with evidence from the US, which suggests that people support restricting voting rights to taxpayers only (Rosenberg and Wejryd Citation2022).

To establish which parental residence requirement is typically acceptable in order to grant territorial birthright citizenship to immigrants’ children is policy relevant. We find that respondents place the cut-off point on average between 5 and 10 years of parental residence. Respondents are 6.1 percentage points and 8.8 percentage points more likely to grant citizenship to children whose parents lived in Italy for 10 and 20 years, respectively, as opposed to three years. There is no statistical difference in willingness to grant citizenship to children with parents who have lived in Italy for five as opposed to three years. This holds when we redo the analysis only on profiles of parents who are residing in Italy with a residency card.

Next, in order of magnitude of effects, Italians are more likely to be in favour of birthright citizenship for children whose parents are Catholic or not religious, as opposed to Muslim, by 6 percentage points and by 4.9 percentage points respectively. However, contrary to expectations, we find only partial support for the relevance of out-group hostility based on immigrants’ origin country. Respondents penalise applicants from Pakistan as opposed to Argentina by 3.7 percentage points, but we find no statistically significant aversion to the inclusion of children whose parents are from the other select countries. This is consistent with evidence on attitudes towards naturalisation criteria which suggests that religion weighs more substantially in people’s consideration of political inclusion dilemmas, compared to ascriptive origin characteristics (Donnaloja Citation2022).

Skill-level and language fluency have smaller, but statistically significant effects. Holding a university degree or a high school diploma as opposed to an elementary school diploma increases the probability of being granted citizenship by 4.2 and 2.3 percentage points respectively. Respondents are also more likely to grant citizenship to children whose parents speak excellent or sufficient Italian as opposed to basic Italian by 6.3 percentage points and by 2.6 percentage points respectively.

Sociocultural indicators of integration to the majority population and loyalty to the country are also less consequential, but do affect people’s likelihood of endorsement of ius soli. We find that both assimilationist and transnational attitudes are rewarded in comparison to participation in origin culture only. Having family friends who are only Italian or having both Italian and foreign friends as opposed to foreign only increases the likelihood of citizenship award by 3.9 and 3.7 percentage points respectively. Respondents are more likely to favour ius soli citizenship for children whose parents support the Italian football team as opposed to the origin country’s team by 3.1 percentage points. We find no difference between those who support both teams and those who supported their country of origin’s team only.

Finally, we find no evidence in support of concerns about the volume of immigration. Respondents are not more likely to grant birthright citizenship to children born into small families, compared to bigger ones; moreover, this is not conditional on country of origin or on religion (see Figures S1 and S2). A possible explanation for this lack of finding is that in a Catholic country like Italy people are unlikely to register the presence of children negatively, even if they fear demographic changes on the aggregate.

All findings are robust to alternative specifications (Figures S3, S4, S5, S6 and S7).

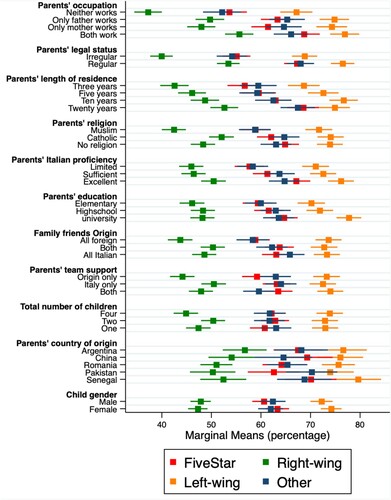

The average acceptance rate varies across groups of respondents (see Table S3). 57.5 percent of respondents with up to a primary school diploma only, 59.1 percent of respondents with a high school diploma, and 63.1 percent of respondents with university degree are in favour of birthright citizenship. 67.7 percent of 18–34 year olds, 58.7 percent of 35–54 year olds and 57.1 percent of over 55 years of age were in favour of ius soli. 73.7 percent of respondents who voted for a left-wing party, 62.1 percent of respondents who voted for the Five Star Movement and 46.5 percent of those who voted for a right-wing party support birthright citizenship. We therefore find the largest between-group variation between groups who voted for different political parties in 2018. This is illustrated graphically in .

Figure 2. Marginal means of support for territorial birthright citizenship by respondent voting behaviour.

Note: MMs calculated after OLS regression of the probability of supporting birthright territorial citizenship where respondent voting behaviour is interacted with the attributes, with clustered standard errors and weights. Open and full squares show MM point estimates; the horizontal lines delineate 95% confidence intervals. To allow comparisons between ‘country of origin’ categories all ‘irregular’ cases were dropped when computing MMs for country of origin. Similarly, Romania was dropped when calculating MMs for legal status.

Yet, in line with other evidence based on conjoint-experiments on attitudes towards immigrants (Hainmueller and Hopkins Citation2015) and naturalisation (Donnaloja Citation2022), we find a broad consensus on what matters for birthright citizenship. Irrespective of their age and educational attainment, respondents do not show significant differences in any of the criteria they apply to their choices, as shown in Figures S8 and S9. In contrast, shows that, depending on whom they voted for, respondents differ in some of the criteria they apply. Right-wing respondents appear to be driving overall average effects for religion and for indicators of socio-cultural integration. Right-wing respondents have a clear preference for Catholics as opposed to Muslim children, whereas left-wing voters do not express such preference. Similarly, if right-wing voters reward children whose parents have Italian as opposed to foreign family friends, or who support the Italian national team rather than the one of their country of origin at major sporting events, left-wing voters do not. Five-star voters and people who voted for a minor party (category: Other) are positioned somewhere in the middle: they have broadly similar preferences to right-wing voters, but differences between attribute levels are not statistically significant. These findings confirm the expectation that right-wing voters are more concerned about the permanent inclusion of culturally different migrants. This is likely due to their attachment to their national identity and to a conservative view about what it entails.

As registered before the experiment, we also explore trade-offs between attributes. We are particularly interested in examining whether behavioural attributes can compensate for the negative attitudes driven by ascriptive attributes. We focus on Muslim as an attribute that elicits hostility and occupation, length of residence and legal status as behavioural measures that could offset such sentiment. We do not find evidence of this, on average. However, since it is right-wing voters who drive the average effect of ‘Muslim’, we estimate the interaction effect for this subgroup only. Here we find that if both parents are in employment, the probability of being in favour of birthright citizenship increases by 5.2 percent for Muslim children, beyond the average effect of being Muslim (see S10).

Discussion and conclusion

Our study contributes to the growing literature on attitudes towards citizenship attribution by examining public attitudes on the contested question of citizenship for immigrants’ children. Using a conjoint experiment design we show how out-group dynamics and economic competition apply to the legal inclusion of children born in Italy to immigrant parents.

Our findings suggest that support for territorial birthright citizenship cannot be disconnected from broader sentiments towards immigrants. This is true across the political spectrum. Our findings suggest that respondents support ius soli under set conditions. These are parental characteristics, especially employment status of at least one parent, regular legal status and length of residence of more than five years. If socio-economic integration (i.e. parental occupation) is a controversial exclusionary criterion of eligibility, residency status and length of residence are not. Existing European ius soli provisions typically rely on legal status and length of residence for citizenship eligibility.

Yet, some differences along political lines remain. Average rates of support for ius soli are starkly higher for left-wing compared to right-wing voters. We also find that right-wing respondents are more reluctant to extend citizenship to children whose parents are Muslim or who are perceived to be less attached to the Italian nation. Such divergence of opinions closely reflects the debate around the introduction of a ius soli principle that preceded the 2018 general elections when the right-wing parties Lega and Fratelli d’Italia centred their electoral campaigns around opposition to the ius soli reform proposed in 2013.

We cannot say if these dynamics apply to Italy alone or also to other contexts. However, in a country where politicians have used the topic for electoral gains and where citizenship law has not changed since 1992, we find openness to change. Our findings may be reason for some optimism for those who campaign for the extension of citizenship policy in Italy and in Europe. We call for further research to examine attitudes towards the inclusion of children of non-citizen parents in other settings, including in those countries where citizenship is made available to minor children under facilitated conditions and to children who arrive in the destination country as minors. Any restriction to ius soli, however democratic, will perpetuate the existence of citizens and denizens, permanently settled members of society without full citizenship.

Moreover, our study focused on people born in Italy to immigrant parents, but 25 per cent of children without citizenship have migrated to Italy as children (ISTAT Citation2020). Any conditional ius soli provision cannot therefore be the sole remedy to the growing population of children without citizenship in Italy and Europe. Socialisation-based citizenship policy, such as Sweden’s, whereby children acquire entitlement to citizenship if they attend a few years of school there, can be an effective policy strategy in combination with ius soli. Future research should investigate public attitudes on these policies both alone and in combination with ius soli provisions. Finally, although crucial, citizenship is unlikely to suffice for the full inclusion of minorities who are often excluded and misrecognised independently of their legal status (Beaman Citation2017). Insight into what it takes for the majority to see the children of immigrants as equal members of society with a right to citizenship can inform political debate about how to overcome these barriers. On the one hand, our findings suggest that demonstrating legitimacy of stay of the children’s parents can be an effective strategy to garner public support for ius soli reform. On the other hand, a campaign focused on economic contributions and social integration of immigrants may resonate with the electorate, but can result in exclusionary policies as voters are at the same time inclined to exclude those who do not meet such criteria. Understanding what drives people’s attitudes to territorial birthright citizenship is therefore essential to identifying the parameters in which politicians and their proposed policies are likely to operate.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.5 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adida, Claire L., David D. Laitin, and Marie-Anne Valfort. 2010. “Identifying Barriers to Muslim Integration in France.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107 (52): 22384–22390. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1015550107

- Alba, Richard, Rubén G. Rumbaut, and Karen Marotz. 2005. “A Distorted Nation: Perceptions of Racial/Ethnic Group Sizes and Attitudes Toward Immigrants and Other Minorities.” Social Forces 84 (2): 901–919.

- Avitabile, Ciro, Irma Clots-Figueras, and Paolo Masella. 2013. “The Effect of Birthright Citizenship on Parental Integration Outcomes.” The Journal of Law and Economics 56 (3): 777–810. https://doi.org/10.1086/673266

- Beaman, Jean. 2017. Citizen Outsider Children of North African Immigrants in France. California: University of California Press.

- Berry, John W. 1997. “Immigration, Acculturation, and Adaptation.” Applied Psychology 46: 5–34.

- Blitz, Brad. 2017. “Another Story: What Public Opinion Data Tell Us About Refugee and Humanitarian Policy.” Journal on Migration and Human Security 5 (2): 379–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/233150241700500208

- Cervi, Laura, Santiago Tejedor, and Monica Gracia. 2021. “What Kind of Islamophobia? Representation of Muslims and Islam in Italian and Spanish Media.” Religions 427 12(6).

- Chandler, Charles R, and Yung-mei Tsai. 2001. “Social Factors Influencing Immigration Attitudes: An Analysis of Data from the General Social Survey.” The Social Science Journal 38 (2): 177–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0362-3319(01)00106-9

- Citrin, Jack, Donald P Green, Christopher Muste, and Cara Wong. 1997. “Public Opinion Toward Immigration Reform: The Role of Economic Motivations.” The Journal of Politics 59: 858–881. https://doi.org/10.2307/2998640

- Davidson, Theresa, and Karlye Burson. 2017. “Keep Those Kids Out: Nativism and Attitudes Toward Access to Public Education for the Children of Undocumented Immigrants.” Journal of Latinos and Education 16 (1): 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348431.2016.1179189

- Dekeyser, Elizabeth. 2017. “Germany’s AfD Wants to Roll Back Birthright Citizenship. The Right-Wing Party Has the Wrong Idea. – the Washington Post.” Monkey Cage. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2017/09/26/germanys-afd-wants-to-roll-back-birthright-citizenship-the-right-wing-party-has-the-wrong-idea/.

- Devakumar, Delan, Geordan Shannon, Sunil S. Bhopal, and Ibrahim Abubakar. 2020. “Racism and Discrimination in COVID-19 Responses.” The Lancet 1194 (395): 10231.

- Donnaloja, Victoria. 2022. “British Nationals’ Preferences Over Who Gets to Be a Citizen According to a Choice-based Conjoint Experiment.” European Sociological Review 38 (2): 202–218. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcab034

- Dražanová, Lenka. 2022. “Sometimes It Is the Little Things: A Meta-analysis of Individual and Contextual Determinants of Attitudes Toward Immigration (2009–2019).” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 87 (March): 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2022.01.008

- Dustmann, Christian, and Ian Preston. 2007. “Racial and Economic Factors in Attitudes to Immigration.” The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy 7: 1–39.

- Egami, Naoki, and Kosuke Imai. 2019. “Causal Interaction in Factorial Experiments: Application to Conjoint Analysis.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 114 (526): 529–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.2018.1476246

- Espenshade, Thomas J, and Charles A Calhoun. 1993. “An Analysis of Public Opinion Toward Undocumented Immigration.” Population Research and Policy Review 12 (3): 189–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01074385

- Felfe, Christina, Martin G Kocher, Helmut Rainer, Judith Saurer, and Thomas Siedler. 2021. “More Opportunity, More Cooperation? The Behavioral Effects of Birthright Citizenship on Immigrant Youth.” Journal of Public Economics 104448 (200).

- Felfe, Christina, Helmut Rainer, Judith Saurer, Julie Cullen, Natalia Danzer, Eva Deuchert, Beatrix Eugster, et al. 2020. “Why Birthright Citizenship Matters for Immigrant Children: Short-and Long-Run Impacts on Educational Integration “Granting Birthright Citizenship: A Door Opener for Immigrant Children’s Educa-Tional Participation and Success.” We Thank Prashant.” Journal of Labor Economics 38.

- Finotelli, Claudia, MariaCaterina La Barbera, and Gabriel Echeverría. 2018. “Beyond Instrumental Citizenship: The Spanish and Italian Citizenship Regimes in Times of Crisis.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (14): 2320–2339. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1345838

- Ford, Robert. 2011. “Acceptable and Unacceptable Immigrants: How Opposition to Immigration in Britain Is Affected by Migrants’ Region of Origin.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37 (7): 1017–1037. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2011.572423

- Ford, Robert, and Jonathan Mellon. 2020. “The Skills Premium and the Ethnic Premium: A Cross-National Experiment on European Attitudes to Immigrants.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (3): 512–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1550148

- Gang, Ira N., Francisco L. Rivera-Batiz, and Myeng-Su Yun. 2013. “Economic Strain, Education and Attitudes Towards Foreigners in the European Union.” Review of International Economics 21 (2): 177–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/roie.12029

- Hainmueller, Jens, and Dominik Hangartner. 2013. “Who Gets a Swiss Passport? A Natural Experiment in Immigrant Discrimination.” American Political Science Review 107 (1): 159–187. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055412000494

- Hainmueller, Jens, Dominik Hangartner, and Teppei Yamamoto. 2015. “Validating Vignette and Conjoint Survey Experiments Against Real-World Behavior.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 (8): 2395–2400. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1416587112

- Hainmueller, Jens, and Michael J Hiscox. 2010. “Attitudes Toward Highly Skilled and Low- Skilled Immigration: Evidence from a Survey Experiment.” American Political Science Review 104 (1): 61–84. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055409990372

- Hainmueller, Jens, and Daniel J Hopkins. 2015. “The Hidden American Immigration Consensus: A Conjoint Analysis of Attitudes Toward Conjoint Analysis of Attitudes Toward Immigrants.” American Journal of Political Science 59 (3): 529–548. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12138

- Hainmueller, Jens, Daniel J Hopkins, and Teppei Yamamoto. 2014. “Causal Inference in Conjoint Analysis: Understanding Multidimensional Choices via Stated Preference Experiments.” Political Analysis 22 (1): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpt024

- Harell, Allison, Stuart Soroka, Shanto Iyengar, and Nicholas Valentino. 2012. “The Impact of Economic and Cultural Cues on Support for Immigration in Canada and the United States.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 45 (3): 499–530. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423912000698

- Hellwig, Timothy, and Abdulkader Sinno. 2017. “Different Groups, Different Threats: Public Attitudes Towards Immigrants.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (3): 339–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1202749

- Horiuchi, Yusaku, Zachary Markovich, and Teppei Yamamoto. 2022. “Does Conjoint Analysis Mitigate Social Desirability Bias?” Political Analysis 30 (4): 535–549. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2021.30

- ISTAT. 2020. Identità e Percorsi Di Integrazione Delle Seconde Generazioni in Italia. Rome: ISTAT.

- Jeannet, Anne-Marie, Tobias Heidland, and Martin Ruhs. 2021. “What Asylum and Refugee Policies Do Europeans Want? Evidence from a Cross-National Conjoint Experiment.” European Union Politics 22 (3): 353–376. https://doi.org/10.1177/14651165211006838

- Kobayashi, Tetsuro, Christian Collet, Shanto Iyengar, and Kyu S. Hahn. 2015. “Who Deserves Citizenship? An Experimental Study of Japanese Attitudes Toward Immigrant Workers.” Social Science Japan Journal 18 (1): 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/ssjj/jyu035

- Kostakopoulou, Dora, and Annette Schrauwen. 2014. “Olympic Citizenship and the (Un)specialness of the National Vest: Rethinking the Links Between Sport and Citizenship Law.” International Journal of Law in Context 10 (2): 143–162. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744552314000081

- Kunovich, Robert M. 2013. “Labor Market Competition and Anti-immigrant Sentiment: Occupations as Contexts.” International Migration Review 47 (3): 643–685. https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12046

- Labussière, Marie, Mark Levels, and Maarten Vink. 2021. “Citizenship and Education Trajectories Among Children of Immigrants: A Transition-Oriented Sequence Analysis.” Advances in Life Course Research 50 (December): 100433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2021.100433

- Leeper, Thomas J., Sara B. Hobolt, and James Tilley. 2020. “Measuring Subgroup Preferences in Conjoint Experiments.” Political Analysis 28 (2): 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2019.30

- Lukac, Martin B., and Alberto Stefanelli. 2020. “Conjoint Experiments: Power Analysis Tool.” https://mblukac.shinyapps.io/conjoints-power-shiny/.

- Mayda, Anna Maria. 2006. “Who Is Against Immigration? A Cross-Country Investigation of Individual Attitudes Toward Immigrants” Review of Economics and Statistics 88 (3): 510–530. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.88.3.510

- McLaren, Lauren, and Mark Johnson. 2007. “Resources, Group Conflict and Symbols: Explaining Anti-Immigration Hostility in Britain.” Political Studies 55 (4): 709–732. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00680.x

- Oonk, Gijsbert. 2021. “Who May Represent the Country? Football, Citizenship, Migration, and National Identity at the FIFA World Cup.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 37 (11): 1046–1065. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2020.1844188.

- Ostfeld, Mara. 2017. “The Backyard Politics of Attitudes Toward Immigration.” Political Psychology 38 (1): 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12314

- Park, Yoosun, Rupaleem Bhuyan, Catherine Richards, and Andrew Rundle. 2011. “U.S. Social Work Practitioners’ Attitudes Towards Immigrants and Immigration: Results from an Online Survey.” Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies 9 (4): 367–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2011.616801

- Polavieja, Javier G. 2016. “Labour-Market Competition, Recession and Anti-Immigrant Sentiments in Europe: Occupational and Environmental Drivers of Competitive Threat.” Socio-Economic Review 14: 395–417.

- Ramos, Alice, Cicero Roberto Pereira, and Jorge Vala. 2020. “The Impact of Biological and Cultural Racisms on Attitudes Towards Immigrants and Immigration Public Policies.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (3): 574–592. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1550153

- Reeskens, Tim, and Tom van der Meer. 2019. “The Inevitable Deservingness Gap: A Study Into the Insurmountable Immigrant Penalty in Perceived Welfare Deservingness.” Journal of European Social Policy 29 (2): 166–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928718768335

- Rosenberg, Jonas Hultin, and Johan Wejryd. 2022. “Attitudes Toward Competing Voting-Right Requirements: Evidence from a Conjoint Experiment.” Electoral Studies 77 (June): 102470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2022.102470

- Rosoli, Gianfausto. 1994. “14: The Global Picture of the Italian Diaspora to the Americas.” Center for Migration Studies Special Issues 11 (3): 305–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2050-411X.1994.tb00769.x

- Scheve, Kenneth F, and Matthew J Slaughter. 2001. “Labor Market Competition and Individual Preferences Over Immigration Policy.” Review of Economics and Statistics 83 (1): 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1162/003465301750160108

- Shachar, Ayelet. 2009. The Birthright Lottery: Citizenship and Global Inequality. Boston: Harvard University Press.

- Sides, John, and Jack Citrin. 2007. “European Opinion About Immigration: The Role of Identities, Interests and Information.” British Journal of Political Science 37 (3): 477–504. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123407000257

- Sniderman, Paul M., Pierangelo Peri, J. P. De Jr. Figueiredo, and Thomas Piazza. 2000. The Outsider: Prejudice and Politics in Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Sobolewska, Maria, Silvia Galandini, and Laurence Lessard-Phillips. 2017. “The Public View of Immigrant Integration: Multidimensional and Consensual. Evidence from Survey Experiments in the UK and the Netherlands.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (1): 58–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1248377

- Tajfel, Henri, and John C. Turner. 1979. “An Integrative Theory of Integroup Conflict.” In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, edited by William G. Austin and Stephen Worchel. Brooks/Cole.

- Tintori, Guido. 2018. “Ius Soli the Italian Way. The Long and Winding Road to Reform the Citizenship Law.” Contemporary Italian Politics 10 (4): 434–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/23248823.2018.1544360

- Urso, Ornella. 2018. “The Politicization of Immigration in Italy. Who Frames the Issue, When and How.” Italian Political Science Review/Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica 48 (3): 365–381. https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2018.16

- Vink, Maarten Peter, and Rainer Bauböck. 2013. “Citizenship Configurations: Analysing the Multiple Purposes of Citizenship Regimes in Europe.” Comparative European Politics 11 (5): 621–648. https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2013.14

- Vink, Maarten, Hans Schmeets, and Hester Mennes. 2019. “Double Standards? Attitudes Towards Immigrant and Emigrant Dual Citizenship in the Netherlands.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 42 (16): 83–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2019.1567929

- Vink, Maarten, Luuk van der Baaren, Rainer Bauböck, Iseult Honohan, and Bronwen Manby. 2021. “GLOBALCIT Citizenship Law Dataset, V1.0, Country-Year-Mode Data ([Acquisition]/[Loss]).” Global Citizenship Observatory.

- Waas, Sabine. 2021. “Failure of Integration or Symbol of Racism: The Case of Soccer Star Mesut Özil.” International Migration 61 (1): 141–153.

- Whitaker, Beth Elise, and John Andrew Doces. 2021. “Naturalise or Deport? The Distinct Logics of Support for Different Immigration Outcomes.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (7): 1889–1918.

- Wright, Matthew, and Tim Reeskens. 2013. “Of What Cloth Are the Ties That Bind? National Identity and Support for the Welfare State Across 29 European Countries.” Journal of European Public Policy 20 (10): 1443–1463. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2013.800796