?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

In this article, we explore how precise information about migrants' working conditions in their destination countries impacts their decision to migrate again upon returning home. Using household data from Kerala and Tamil Nadu from 2020–21, we study return emigrants (REM) who returned during the first COVID-19 lockdowns in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. Through a binary choice model, we discover that negative experiences in the destination country significantly influence the decision to re-migrate. Specifically, issues with salary payment and reduced working hours make re-migration less likely. We then apply a two-stage multinomial regression to identify the causes of these negative experiences and how they shape a migrant's future decisions. We conclude that such experiences discourage re-migration and increase the preference to work in the country of origin. Our research offers insights for shaping future migration policies in the region.

KEYWORDS:

1. Introduction

According to Article 37 of the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families,

Before their departure, or at the latest at the time of their admission to the State of employment, migrant workers and members of their families shall have the right to be fully informed by the State of origin or the State of employment, as appropriate, of all conditions applicable to their admission and particularly those concerning their stay and the remunerated activities in which they may engage as well as of the requirements they must satisfy in the State of employment and the authority to which they must address themselves for any modification of those conditions. (OHCHR Citation1990)

In other words, which are germane to the scope of this paper, international migrants are entitled to know the precise nature of their working conditions before their departure. However, we know this to not be the case across several migration corridors, not least because of the limited ratification by major countries of destination (henceforth CoD) and countries of origin (henceforth CoO). Nor is it practically possible for a migrant to have complete awareness because of behavioural biases; migrants may be predisposed to view the upcoming migration in a positive light or out of necessity and they may resist such knowledge. This paper aims to generate new scholarship which looks into the impact such knowledge can have on the migration decision.

We use the unique context of return migration of international migrants to their CoO as a result of COVID-19, to study how precise information of working conditions (henceforth PIWC), or direct experience of working conditions in the CoD, affects the decision to migrate again. Our study is set in the India-GCC corridor, which is one of the largest migration corridors in the world; Indians comprise 30% of the expatriate workforce in the Gulf states, and 90% of India’s expatriate labour being sent to the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries (Sasikumar and Thimothy Citation2015). Not only has this paved the way for international bilateral cooperation that facilitates the movement of people, but also for the flow of counter-cyclical remittances and foreign aid. Furthermore, India is both the largest sending country and the largest recipient of remittances in the world (Press Trust of India Citation2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented the biggest challenge in recent history to this corridor, by devolving from a health crisis into a migrant crisis due to its unprecedented nature (World Bank, Citation2020). When the first cases started appearing in multiple locations across the world, the declaration of lockdowns allowed government’s breathing room to contain the virus. However, these lockdowns were not costless; their negative effects were felt differentially across populations, conditional on socioeconomic characteristics and highly correlated with attendant inequality. The process highlighted existing weaknesses in social protection systems, especially by temporary emigrants or guest workers in richer countries. Several of them were left bereft of incomes, or even the ability to return to their countries of origin (Ghani and Morgandi Citation2023; Mia and Griffiths Citation2020; Rahman et al. Citation2023; Rajan and Arcand Citation2023).

Faced with several stranded migrant workers in multiple CoD, especially the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, the Indian Government responded with a repatriation exercise of immense scale and logistics (Rajan and Akhil Citation2022; Rajan and Arokkiaraj Citation2022). The lockdowns in the GCC were difficult for several emigrants (regular and irregular) who faced mixed experiences from their employers, which added to their economic and social uncertainty (Babar Citation2020; Shah and Alkazi Citation2023). Reductions and withholding of wages, threats of termination and unsafe working conditions, and a lack of social security because of the pandemic and their precarious housing situations were common (Foley and Piper Citation2021; Weeraratne Citation2023). Several migrants returned to escape these circumstances; more than 9 million Indians returned as of 31 October 2021 under the Vande Bharat Mission designed for repatriation (Rajan and Pattath Citation2022a; Citation2022b; Citation2023).

This setting provides a unique platform from which to study the effect of PIWC in the CoD on the future plan upon returning to the CoO. It is unique because of three reasons. First, it involves a situation of return for a large proportion of the migrant stock because of a covariate shock, i.e. COVID-19 that affected all of them. Even if they had different levels of insulation from the socioeconomic effects of COVID-19, they were all at risk of exposure to an unprecedented disease and had to be subject to the same overarching lockdowns and restrictions of mobility. This created a situation that did not discriminate solely based on initial characteristics which may in turn have afforded different privileges.

Second, they returned for an indefinite period of time to their CoO. Return migration is not an easy concept to universalise under one definition, partly because of the heterogeneity of return and its uncertain existence as a part of the migration continuum rather than an endpoint (King and Kuschminder Citation2022). The fact that almost all the REM were destined to be back in the CoO without an immediate possibility of remigration because of exogenous factors like the governance of international travel, resumption of work, and global business cycles affecting their employment, meant that each of them had a period of time available in their home environment to take stock of their migration experience so far, their most recent experience as a migrant during COVID-19 in a foreign country, and their future plan once things returned to some degree of normalcy.

Third, and most important, is that all the migrants who returned had an additional covariate shock; they were all exposed to the information of what it means to be an international migrant in the jobs they occupied. PIWC in the returned state, by way of direct experience, accentuated by an additional experience of working or not working during the initial months of COVID-19, were available to each of these REM. A key assumption of our analysis is that we assume the REM takes this information into account in how they think about their future plans after returning during COVID. We hypothesise and attempt to prove that the variation in characteristics or initial conditions of these mi- grants lends itself to idiosyncratic shocks experienced by them, i.e. their different experiences of working conditions. These experiences are what we expect to ultimately have an important bearing on their future decisions.

We take advantage of rich survey data collected from households to which a GCC migrant returned during COVID- 19, namely Return Emigrant Surveys from Kerala and Tamil Nadu. Designed and conducted by the senior author during December 2020- April 2021, sampled on a list of REM who returned in the Vande Bharat repatriation flights to India, the dataset contains data on 2458 households. The data is divided into modules that capture the employment and migration history, household details, repatriation and rehabilitation details, skills, future plans, and remittances of these REM (Rajan and Pattath Citation2021). By testing associations between the intended future plan of these REM at the time of the survey and a range of different experiences in the CoD, we study how PIWC in the CoD affects future migration decisions.

An important caveat for our results is that some of the survey questions regarding bad experiences related to working conditions concern the period covered by COVID-19 lockdowns and not the whole experience of migration in the CoD. Therefore, another key assumption in our paper is that the precise knowledge of the migration experience is largely proxied by the experiences of working or not working during COVID-19. We argue that these experiences are more salient for the REM reporting their future plan in the survey for three reasons. First, it encapsulates their most recent experience before return and will be stronger in their memory, especially if the experiences are negative (Reed and Carstensen Citation2012).Footnote1 Second, the uncertainty of the pandemic at the time of the survey, and the conditions that influenced the REMs to choose to be repatriated have no defined end-date at the time of the survey. If the REM is to consider the impact of previous migration experiences on their future decisions related to migration, there is every reason for them to extrapolate their personal experience from the prevailing circumstances of COVID-19 into what the future might look like. Third, traumatic experiences have a strong effect on people’s decision making in spheres of life that involve information asymmetry and trust. This has previously been observed in consumption of primary healthcare (Alsan and Wanamaker Citation2018; Martinez-Bravo and Stegmann Citation2022). Since the decision to migrate internationally involves information asymmetry which is partly mediated by the migrant’s optimism and trust in her safety, we can reasonably assume that the memories of traumatic experiences have a significant bearing on future migration decisions (Katz and Stark Citation1987).

In this paper, we employ multinomial and binary choice models to investigate whether negative experiences encountered by return migrants (REM) in their CoD are econometrically important predictors for their decision to migrate again during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further examination of the various options available to the REM revealed that difficulties with salary payment and reduced working hours were particularly likely to discourage re-migration. To further test our findings, we also conducted a two-stage multinomial regression analysis to identify the factors con tributing to negative experiences and the factors influencing the REM’s future migration decisions. The results of this analysis provide stronger evidence that negative experiences discourage re-migration and increase the likelihood of the REM seeking employment in their CoO.

The following sections will proceed this way: section 2 discusses the context of COVID-19 in India from the first cases to the period of lockdowns covered by the dataset. Section 3 reviews the literature we situate this paper in. Section 4 describes our data and empirical methods. Section 5 presents our analyses and results and Section 6 concludes with policy implications.

2. Context of COVID-19 in India

Similar to most governments around the world, the Government of India responded to the first cases of COVID-19 by imposing restrictions on mobility. A 21-day lockdown starting from late-March 2020 was followed by extensions in a bid to ‘flatten the curve’. A complete ban on the operation of any establishments as well as inter-state and inter- national travel led to several people, especially internal and international migrants from India being displaced and stranded across geographies. In the context of our study, this state of being stranded is key because of two reasons. First, it exposed deep fault lines within the relationship between migrant workers and their CoD, as their vulnerabilities were brought to the fore and even enhanced in some cases. In the context of a covariate shock like COVID-19 which affected people across the world indiscriminately, international migrants, especially those from developing countries, faced particular idiosyncratic shocks due to their differentiating characteristics from the rest of the population. Some of these characteristics include existing barriers due to their foreign nature such as inequities in access to social protection as well as differences in surviving in a hostile environment which already embodied differences of culture and language. Second, the aforementioned insecurities of these international migrants coupled with mis- treatment faced by several sections of workers and the potential risk of it necessitated the desire to return to their CoO among international migrants.

As a result, several international migrants applied to return when the Government of India began a repatriation mission called the Vande Bharat mission in May 2020. The official number of people who returned as of October 2021 exceeds 9 million.Footnote2 This figure is anywhere between 50 and 70% of the stock of Indian diaspora in the world.Footnote3 The precise details of the mission as well as standard operating protocol are covered by Rajan and Arokkiaraj (Citation2022). The mission involved bringing back Indian nationals but the efforts were hindered by diplomatic slowness, red-tapism, and inadequately tailored homogenous technological approaches (such as e-registrations on portals). Furthermore, REM were inconvenienced by exorbitant prices compared to the pre-COVID rates, inadequate as well as expensive quarantine facilities in the earlier stages due to poor planning and capacity by the respective state governments. Naturally, demand for repatriation exceeded supply, as the capacity was simply not adequate given constraints with operational airlines as well as diplomatic air bubbles. Most of the requests for repatriation came from the India-GCC corridor, the latter governments having urged the Indian authorities to repatriate their nationals, recognising earlier the scale of migrant stock in their territories.

Kerala and Tamil Nadu are important states not just in the context of international migration of Indians, but also for the India-GCC corridor. While migrants from Kerala have contributed to nation building in the Gulf states since the 1970s as a result of the wage differentials and diaspora effects of the first waves of emigrants aided by pro-emigration state governments, migrants from Tamil Nadu are currently some of the largest diaspora groups in these countries with rapidly increasing trends over the last couple of decades (Khan and Arokkiaraj Citation2021; Rajan et al. Citation2017; Zachariah, Mathew, and Irudaya Rajan Citation2001a, Citation2001b). While Kerala’s handling of the initial waves of COVID-19 was exceptional compared to that of other states, neighbouring Tamil Nadu’s was similarly effective in terms of restricting the caseloads (ReliefWeb Citation2023; Research Citation2023). Given that the Vande Bharat mission was a national effort with flights repatriating Indian nationals to all states, Kerala and Tamil Nadu received their REM stock around similar timelines. Both states set up rapid testing facilities at the airports of arrival and passengers were either directed to state quarantine facilities or to private facilities of their own. Rajan and Pattath (Citation2021) find considerable heterogeneity in the arrival, testing, and quarantine experiences of the REM in Kerala. In general, Kerala’s management of the pandemic for most of 2020 was lauded inter- nationally not just because of quick and effective responses by the state government and health department but also because of grassroot organisations of public health infrastructure. Even during later waves in which India’s caseloads increased exponentially, Kerala was among the few states that did not experience a severe shortage of hospital beds, ventilators, oxygen supply and essential medicines. In fact, Kerala supplied these to other states in cases where there was a surplus (NDTV Citation2023).

With the help of the Kerala Migration Survey which consists of two decades of longitudinal data on migrant house- holds that is representative for state level figures of migrant demographics and state fiscal measures, the public authorities could estimate accurate requirements for hospital beds, testing kits, and quarantine facilities before the repatriation missions began and allocate the required public outlays (Rajan Citation2020). Through the agency responsible for the welfare and provision of information to emigrants, NORKA roots, a pravasi (migrant) registration system which helped inform the sampling design for the dataset used in this study. The study also recorded several instances of wage theft, which became a commonly reported issue in the context of COVID-19 migration, but the options for redress are still vague for REM. The existing mechanisms permit an NRI returnee to grant a power of attorney to the Ministry of External Affairs to fight a case on their behalf through the Indian Embassy in the relevant country (Rajan and Pattath Citation2022a). While future migration flows may continue with modifications to skill specialisations and sectoral flows, these individual instances of wage theft may have strong network effects on deterring migration among those in the know.

3. Relevant literature

Because several definitions abound, it is important to clarify the exact connotations and essence of the terms we use in this paper. While Gmelch defines return migration as the movement of migrants to their homelands to resettle, re-emigration is defined as the event when those return migrants emigrate again(Gmelch Citation1980). According to them, frequent movement between places is defined as circular migration. Adapting these definitions to our setting requires focusing on the aspect of intention and volition in the movement of these emigrants. For example, there could have been migrants who intended to migrate permanently, but were forced to return. In the case of COVID-19, several return migrants were forced to return because of adverse circumstances in the host and/or source countries related to their jobs and income, place of stay, legal status, and health. In such circumstances, their decisions carry varying degrees of volition which also affects their subsequent intentions and decisions in the migration continuum. This blurring of opposite categories is acknowledged by several scholars as a spectrum of experiences (Erdal and Oeppen, Citation2018). In this paper, we deal with the return migration of individuals from various host countries to two Indian states, Kerala and Tamil Nadu, as a result of COVID-19. These migrants returned with varying degrees of volition. Their subsequent intentions upon return may include re-emigration or resettlement, and we focus on the intention by closely studying the factors related to either intention. We also focus specifically on subsequent intention after return given the unique nature of the COVID-19 return migration phenomenon and the nature of the data at our disposal, in which we are able to observe the determinants of return, and the intended future plan or either re-emigration or resettlement/reintegration. In what follows, we survey the literature on re-emigration intentions following return migration conditional on experiences in the host and source countries.

Cerase’s (Citation1974) fourfold typology of return is among the most well-known frameworks to understand return migra tion, linking stage of integration in the host country with the impact return migrants create in their homeland. This framework distinguishes return of failure (quick return with little to no savings), return of conservatism (savings are brought back which are then invested), return of innovation (after considerably longer stays, the migrant returns with knowledge to invest at home) and return of retirement (upon completion of migration goals with considerable savings). Other frameworks by Battistella (Citation2018) also list returns based on volition, differentiating between completion of contracts, setbacks which may force a return, or crisis returns (political failure, repatriation, environmental shock).

However, re-emigration is less organised, and does not exist independently of the motivations that influenced the decision to return (Davids and Houte Citation2008). In fact the typologies of return also indicate various factors affecting the decision to the re-emigrate. In our setting, the periods of interest start from the declaration of the COVID-19 lockdowns in the host countries to the decision to return to when the survey was conducted which the REM was in the CoO. In this paper we focus on factors relating their wage payments in the host country, distressed situations in the host country, protective measures and prospects in the CoO, and skills possessed by the REM at the time of survey.

When individuals self-select into temporary migration, it may be part of an optimal decision-making process in order to maximise lifetime utility (Djajić and Milbourne, Citation1988). This process yields an optimal amount of time that the migrant intends to work in the host country, in order to accumulate savings or to take advantage of higher returns in the origin country by way of remittances and investment. But when the intended time is cut short because of exogenous shocks that also affect the volition in return, re-migration may become more salient for the migrant. Borjas and Bratsberg (Citation1994) document re-emigration due to inability to complete the migration plans with respect to target savings. Therefore, wage is an important component of the migration plans, particularly since wage differentials between the home and host country influence migration preferences. In addition, Wolff (Citation2015) noted that temporary migrants are 10 percentage points more likely to remit while the amounts remitted are almost twice as high. Chabé Ferret et al. (Citation2018) also find that temporary migrants are more likely to invest in the CoO and less likely to invest in the host country. The savings held by these migrants are low in both cases. Therefore, disruptions to wage in any form (reduction, withholding, delay, or reduction in the number of days) are particularly bad instances in the migration experience for temporary migrants.

Whether a bad experience affects a subsequent re-emigration decision is a relatively new question in the literature, and one that we explore in this paper. Caron and Ichou (Citation2020) discuss the unfulfilled expectations hypothesis wherein migrants who are unable to complete their migration goals in terms of incomes, savings, or remittances will be likelier to re-emigrate. However, in cases of difficulties related to wage payments, the relationship could be ambiguous. On the one hand, bad experiences with the host employer relating to payment of wages may negatively affect the experience of migration overall, dissuading migrants from remigrating to that or similar locations. This could be pronounced for temporary migrants as in our case, especially those with low saving behaviour whose remit tance frequency and amounts are higher. On the other hand, migrants who have good relations with their employers and conditional on the type of firm or establishment may prefer to wait out the crisis and re-emigrate when prospects are better. It could also be the case that certain temporary emigrants who are very dependent on the wages because of the wage differential also do not base their intentions to re-emigrate on the non-wage related bad experiences with the employer.

Broader categorisations of bad experiences in the host country may also affect re-emigration intentions. When the migrant comes home, they are immediately in a negotiation with their dual identities regarding the change of environment (Kunuroglu, Van de Vijver, and Yagmur Citation2016). As a result, the migrant involuntarily engages in comparison, which may be magnified in the temporary migration case where there is always a goal of returning home as soon as the savings expectation is fulfilled. For someone encountering legal or employment related difficulties, adverse health situations and crisis contingencies, and being forced to stay in cramped accommodation, the comfort of their own homes and desire to resettle can be attractive (Cassarino Citation2004). While a patriarchal household where the division of within-household labour is unequal may lure an REM with such comforts, the same makeup of these households may also influence the migrant to temporarily ‘sacrifice’ for his family. Remittances too matter in this context, because the drying up of counter-cyclical cash flow during a prolonged period of crisis may affect the family’s ability to smooth consumption. Especially if there are significant investments or savings to divest or draw from. Therefore, an excessive reliance on remittances, which in turn depends on the income level, may spur re-emigration.

Networks in foreign countries are vital for migration flows. Large stocks of migrants in these countries over time may contribute to diaspora effects that affect bilateral flows and access, incentivising re-migration (Beine, Docquier, and Ozden Citation2011; Khan and Arokkiaraj Citation2021). However, there may also be exodus effects despite initial large migrant stocks based on negative shocks. Conditions in the source country, too, may affect the re-emigration decision. Upon return, the migrant (especially one who has faced wage reductions) may look for jobs or consider investing their savings into a business or start up. On the one hand, unemployment due to lack of employment opportunities in the source country and worsening of the possible baseline competition for less attractive jobs may be a factor that influences re-emigration (Wahba Citation2021). However, we do not have unemployment data on the REM at the time of survey. On the other hand, we have information about the migrants’ investment in start ups, their degree of awareness about post- crisis employment programmes aimed at migrants. Such protective factors are expected to have a positive influence on the decision to re-emigrate.

4. Data description and empirical strategy

The COVID-19 REM Survey was conducted from January to May 2021 on a total sample size of 2458 REM from Kerala (1878) and Tamil Nadu (694). The survey was conducted by the Centre for Development Studies (CDS) and the International Institute of Migration and Development (IIMAD) using the Computer Assisted Telephonic Interviewing (CATI) method. The sample was randomly drawn from a partial list of expatriates who returned to Kerala and Tamil Nadu from any international destination during April 2020 to November 2020. The sample is not weighted by the population of the districts, and hence lacks representativeness on that dimension and is broadly a non-probability sample. The questionnaire is divided into sections regarding the emigration history of the REM, the demographic and family characteristics, return experience, future plans, remittances, and household assets (see Rajan and Pattath (Citation2021) for the report of the survey and questionnaire).

The goal of the empirical analysis is to examine the association between different forms of bad experiences faced by the REM during the COVID pandemic and the future plans of these REM regarding migration or resettlement. In our empirical analysis, we estimate two baseline one-stage regressions using different dependent variables. In the first regression, we analyse the determinants of future plan using a multinomial logit framework. Here, the categorical dependant variable consists of the options of the future plan variable, which includes the options (1) start a new business in Kerala/Tamil Nadu, (2) re-emigrate to get a new job, (3) re-emigrate to the same job as before, (4) retire from work and (5) seek new job in Kerala/Tamil Nadu. In the second regression, the dependent variable is a binary variable that takes the value of 1 when the return emigrant plans to re-emigrate later and takes the value of 0 when he/she plans to stay in India as measured by the remaining options. As the dependent variable is a binary variable, we use a GLM model with a logit cumulative distribution function. Therefore, the form of our regression models is the following:

Age

Gender

District of origin

Last location of stay

Education

Duration of stay since return

Prior migration experience

Network in the other countries

Table 1. Summary statistics – Kerala.

Table 2. Summary statistics - Tamil-Nadu.

Through our empirical model, the goal is to identify the treatment parameter of interest taking advantage of the unique setting to reduce sample selection bias. Even though there are many unobservable variables that simultaneously affect both the re-emigration decision and our predictors, the nature of the COVID-19 shock was all-encompassing, necessitating a situation of returning to the country of origin among most international migrants in the India-GCC corridor. In the returned state, all REM have received an information shock, wherein they have precise knowledge and experience of the working conditions in their previous jobs (PIWC). That these experiences vary, and depend on initial conditions of the REM such as age, gender, education, district of origin allows for a further investigation of the exact typology of REM who may be subjected to difference experiences of working conditions in the first place. We proceed to investigate our research question in two ways.

In our analysis, we use a Generalised Linear Model (GLM) function and a Multinomial Logit Model (MNL), the latter in two ways. While the first regression model employs the logistic function to model the binary response of re-migration to the CoD or another country vs. staying back in the CoO determined by the different experiences faced by the REM, the second provides an insight into the relative probabilities of each choice of futureplan, expanding on the results of the first. Our third model takes a more careful view as we describe in the next paragraph. Regarding the aforementioned two models, although we do not claim that these experiences are exogenous, thereby allowing us to make causal inferences about their impact on the future plan, the endogeneity of these regressors is not as obvious as a result of the unique setting in which the survey data has been captured. Selection and more broadly, simultaneity bias is not apparent in this setting because of the unexpected nature of COVID-19, which proceeded to necessitate the process of return from the CoD and the subsequent intention of a future decision regarding the REM’s mobility. Regarding omitted variable bias, we try our best to control for the variables that could affect the regressors and the dependant variable.

However, we go a step further to test the validity of these results, and we turn to the determinants of these experiences themselves. We again use a multinomial logit framework, this time assuming a possible endogeneity of the regressors (the variables capturing different experiences) and we control for these using a two-stage regression. In the first stage, we perform a logit regression, where the dependent variable is one of the binary variables that indicate different experiences of the REM and the characteristics of the REM are modelled as predictors. In the second stage, the predicted probability obtained from the first stage along with the characteristics of the migrant enter as predictors against binary choices of the categorical variable representing each future decision of the REM. In all three models, the fixed effects are included at the district level.

5. Analysis and results

5.1 Binary model - marginal effects

presents the results of our regression analysis for different forms of lost wage. The dependent variable has a binary value; it takes the value equal to 1 when the REM intends to remigrate to a new or the old job and equal to zero when she intends to stay in her home town. As we use a GLM model, we cannot interpret the size of the coefficients. For this purpose, we calculate the marginal effects for each variable. shows the marginal effects for different forms of lost wage. We find that for an REM who is due a salary and had their wages reduced would be 35% and 32% less likely to remigrate respectively. However, working without a salary, having the number of working days reduced, and having poor living conditions have no significant effect on the decision to remigrate. It is meaningful that age is negatively related and highly significant since older REM tend to retire/seek a job in the place of origin especially because permanent residency in the GCC is not possible.

Table 3. The impact of different experiences on remigration decision, binary dependent variable, marginal effect.

As discussed in the review of the literature, the overall effect of negative experiences could be ambiguous. We see this partially through the strongly negative and significant effect of being owed salaries and facing reductions in the amount of salaries and partially through the insignificance of the remaining experiences on the decision to remigrate in our first and second models respectively.

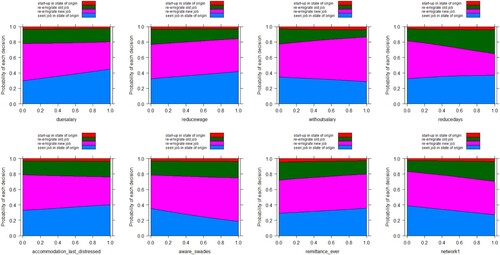

5.2 Multinomial model

presents the results of the one-stage MNL regression of different choices of future plan on different experiences faced by the REM. Seeking a job in the CoO (in this case in the states of either Kerala or Tamil Nadu) is the base category. When the REM is due a salary (Due Salary), the associated coefficients are negatively significant for the three given choices. Reduction of wages (Reduce Wage) are associated with a similar negative coefficient for remigration to the old job. When the REM’s working days are reduced (Reduce Days), the sign of the coefficient reverses with respect to re-emigrating to the old job but remains negative for re-emigrating to a new job. Simply reading this result suggests that a reduction of working days might either not disincentivise going back to the old job, or that it might even be an incentive to go back as the employee might have agreed to the reduction given the circumstances of COVID- 19, or may have been promised the guarantee of continuing their job after the uncertainty regarding COVID-19 was reduced in the future.

Table 4. The impact of different experiences on remigration decision, one stage MNL model.

However, the raw coefficients from a Multinomial Logit are not very informative as to even the direction of the marginal effects on the probability of a given outcome. Therefore, we produce plots of the effects of each of the main predictors on the probability of each future plan as demonstrated in (Arcand et al. Citation2021). We report these in the various panels in . These plots can be interpreted taking the example of the first panel concerning duesalary in the following way: an increase in the probability of the REM being owed a salary monotonically reduces the prob- ability of re-emigrating to a new job by more than it reduces the probability of re-emigrating to the old job. However, it increases the probability of seeking a job in the state of origin, i.e. Kerala or Tamil Nadu as the case may be, for the REM in our data. This result argues that the negative experience of being owed a salary during the uncertain months of COVID-19 were damaging enough for the REM to not just wish to return but also to not want to go back, and rather to seek a job their home state.

Similarly from , an increase in the probability of experiencing a reduction in wages and/or working for free without any salary reduces the probability of migration to the old job. But the former experience is associated with an increased probability of wanting to seek a job in the state of origin, while the latter experience is negatively predicts seeking a job in the state of origin at the expense of seeking a new job in a new CoD. An explanation for this result could be that working without a salary was a conscious choice made by the REM to bide their time before returning to India, with an expectation that they would migrate again to a new job which would be different to the unexpected and unique working conditions that were prevalent during COVID-19. Another result of note is that losing working days and working hours increases the probability of remigrating to the old job while decreasing the probability of remigrating to a new job. One possible explanation for this result is again an acknowledgement that the situation of reduced hours was peculiar to COVID-19 and a guarantee of better working conditions in their old job after remigration.

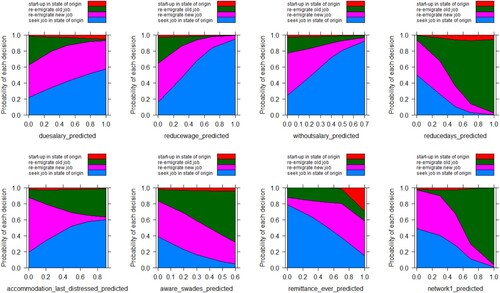

5.3 Two stage MNL

We now turn to the two-stage regression. presents the first stage results of regressing each determinant variable (four wage experiences, accommodation situation in the CoD, awareness about SWADES, and presence of a network in GCC countries) against a set of predictors, the initial conditions of the REM, at the individual level. The coefficient of duration of last stay is interesting qualitatively as it is negatively significant in two of the experiences, namely that of reduction of wages and reduction of working days, indicating that a longer duration of stay is associated with a lower probability of having had a bad experience with the employer during the COVID-19 lockdown. In addition, longer stays are associated with lower reliance on sending remittances, probably indicating a built up stock of savings or an investment in the CoO that pays dividends that support expenditure at home.

Table 5. First stage results/Logit/Migrant experiences and their characteristics.

Using the the predicted probabilities obtained from the first stage along with the characteristics of the migrant, we estimate the probabilities of each future decision in with seeking a job in Kerala/Tamil Nadu as the base category. The different experiences are hypothesised to be important determinants of the future plan. The columns of show these effects for each of the three future decisions compared to seeking a job in the CoO.

Table 6. The impact of different experiences on remigration decision, two stage MNL model.

As in the previous one-stage MNL, we report probability plots of the relative choices of future plan in . The three wage variables, namely due salaries, reduction of wages, and being asked to work without salary are mostly responsible for the cases in which the future decision is to seek a job in Kerala/Tamil Nadu. It aligns with the findings in the literature that negative experiences related to wage, and in the case of COVID-19, wage theft by the employers during an already harsh and unpredictable period has a big role to play in deterring future migration upon return. One could argue that these experiences were traumatic for the REM, thereby strongly influencing their outlook on the migration experience also considering recall bias at the time of the survey. In each of these three cases, the probability of wanting to resettle in Kerala/Tamil Nadu monotonically increases.

Remigration to a new job is generally spread out across experiences and is therefore not very meaningful although most cases have a similar trend of monotonically decreasing with increase in the probability of the negative experience in the CoD. Remigrating to the old job is a much more interesting result, with most of the conducing being done by reductions in working days and presence of strong networks in either the last CoD or other countries outside of India. Both these results are in line with the literature, and the latter is further evidence of diaspora effects that suggest positive incentives for migration when there are good social networks in the CoD.

6 Conclusion

During the run-up to the recently concluded FIFA World Cup, the international media attempted to highlight difficul- ties encountered by migrants from low-income countries in the Gulf states. Because of their presence as ‘temporary’ workers outside the social contract, the state treats them like the subservient underclass, lacking humanity, let alone compassion. The India-GCC migration corridor is an archetype of this phenomenon and posts some of the largest proportion of international migrant flows globally. While the question ‘why do they migrate to these countries with poor working conditions’ may be a perplexing question for many who cannot empathise with the initial factors that drive migrants to do so, academics are clear about a range of determinants of migration. Re-migration however, is a different question and one that is not easy to investigate because return migration still remains a process that lacks a universal definition, a precise set of conditions, and one in which surveying the migrant is a tall order. What is also important while investigating the determinants of re-migration is to have a setup that allows the migrant to have both agency to make their future decisions and a set of factors that make this decision ambiguous to the researcher.

COVID-19 created a situation wherein a large proportion of international migrants returned to their countries of origin during the initial lockdowns. These waves of return were facilitated by large repatriation missions in countries like India and the Philippines and these missions were in turn motivated by the respective Governments’ awareness of the precarious positions of several migrants from their countries (Opiniano and Ang Citation2023). This wave of return is unique because of its coverage of a majority of the migrant stock and the duration for which they returned. It is also unique because all the migrants who returned had two covariate shocks, wherein they were subject to the pandemic which was unprecedented in nature and whose health implications required all to adopt similar measures involving restricted mobility, economic uncertainty, and social distancing. The second covariate shock, that which was realised in the returned state, was that of information. With the precise knowledge of what migration previously entailed for them in their jobs, they had to make the decision on their future. Our survey data captures their intent, if not the decision itself, and we model this as a function of their previous migration experience and specifically their experience during COVID-19.

Our results highlight the role of bad experiences in affecting the decision to re-migrate vs. staying back at home, when the migrant is in the returned state. Through a combination of different empirical methods that take advantage of our rich dataset, we provide evidence that delineates the role played by different experiences on each type of future decision. We control for initial conditions or migrant characteristics and predict the set of determinants that in turn predict the future plan of the migrants, to address the causal pathway suggested by our written theory.

Our results have implications for how we think about migration decisions in the migration continuum of circular migration patterns in contexts where temporary migration is praxis. We see that migrants are not numb to difficult experiences and will update their stated preferences according to the information available to them. Even though it was previously thought that migrants were resilient to the harshest conditions, explained by the persistence of large migration flows and migrant stock in the Gulf countries, our results suggest that it could have been inertia more than volition which pushed these migrants to endure these conditions. The situation of return necessitated by COVID-19, and available to those whose home countries facilitated them, allowed for a period of introspection that led to the differences in stated preferences, conditional on the idiosyncratic shocks faced by the REM.

Another important implication of our result is that such a study was possible due to the availability of high quality data collected at a crucial period of time. It further highlights the need for routine and representative data collection among migrants, including a systematic way to record and document information about the process of return. While COVID-19 may be an anomaly that allowed for such an exercise, it is certainly of utmost importance to observe the differential effect of smaller shocks in the CoD on the cross-border movement of migrants. Such data and its periodic analysis by researchers and international organisations will enable better ex-ante prediction of migration flows, which can then lend itself to policy interventions as the case may be. Current endeavours to demystify the aftermath of shocks such as COVID-19 in a representative way in the region rarely benefits from the availability of primary data at scale. Instead, insights are generated either through in-depth interviewing (Rahman, et al., Citation2023) or through primary data collection efforts that adaptively use phone survey methods (Adhikari et al. Citation2023) or through innovative pooling together of multiple sources of secondary data as demonstrated by Farooq and Arif (Citation2023). Another pertinent example is the use of the Kerala Migration Survey’s 20 year panel which is representative spatially and temporally by Limani and Arcand (Citation2023) to estimate that Kerala’s migrant stock may return to and even exceed pre-pandemic levels relatively quickly.

Finally, it is important to publicise results like these to the CoD, which may continue to receive similar if not higher stocks of international migrants as cross-border mobility resumes as a result of wage differentials and job demands from relatively low-income countries. Humane and just treatment of workers is no longer a point of negotiation, de spite the harsh realities, and CoO need to advocate for their migrants by highlighting the disincentivizing effects that we show here as a negotiation tool. Migrants proved extremely resilience during the first stages of the pandemic, with remittances again proving countercyclical and exceeding the World Bank’s predictions. CoO owe a debt of gratitude to their migrants for their continued remittances, and while the international migrant certainly deserves better, the treatment received by several of them might just have been the last straw.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 In our analysis we control for age of the REM to mediate the relationship between selective memory and aging. Additionally we control for the time elapsed since return to the survey, to account for memory in relation to time.

2 This figure records return passengers in Vande Bharat flights to each state in India as published by the Ministry of External Affairs. It could possibly contain duplicates.

3 Consisting of individuals who are citizens of India but are residing in a foreign country and hold a valid Indian passport) and people of Indian origin or PIOs (foreign Citizens except for nationals of Pakistan and Bangladesh, who have either held an Indian passport at any point in time or their parents/grandparents/great-grandparents were permanent residents of India or are spouses of an Indian citizen.

References

- Adhikari, Jagannath, Mahendra Kumar Rai, Mahendra Subedi, Chiranjivi Baral 2023. “Foreign Labour Migration in Nepal in Relation to COVID-19: Analysis of Migrants’ Aspirations, Policy Response and Policy Gaps from Disaster Justice Perspective.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (20): 5219–5237. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2024.2268983

- Alsan, M., and M. Wanamaker. 2018. “Tuskegee and the Health of Black men.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 133 (1): 407–455. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjx029

- Arcand, J. L., D. Sylvan, A. Aladysheva, and E. Gadjanova. 2021. “Guns, Germs, and Slaves: an Alternative View of the Colonial Origins of Comparative Development”.

- Babar, Z. R. 2020. “Migrant Workers Bear the Pandemic’s Brunt in the Gulf.” Current History 119 (821): 343–348. https://doi.org/10.1525/curh.2020.119.821.343

- Battistella, G. 2018. “Return Migration: A Conceptual and Policy Framework.” International Migration Policy Report Perspectives on the Content and Implementation of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, 3-14.

- Beine, M. A., F. Docquier, and C. Ozden. 2011. “Diaspora Effects in International Migration: Key Questions and Methodological Issues.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (5721).

- Borjas, G. J., and B. Bratsberg. 1994. “Who Leaves? The Outmigration of the Foreign-Born.”

- Caron, L., and M. Ichou. 2020. “High Selection, low Success: The Heterogeneous Effect of Migrants’ Access to Employment on Their Remigration.” International Migration Review 54 (4): 1104–1133. https://doi.org/10.1177/0197918320904925

- Cassarino, J. P. 2004. “Theorising Return Migration: The Conceptual Approach to Return Migrants Revisited.” International Journal on Multicultural Societies (IJMS) 6 (2): 253–279.

- Cerase, F. P. 1974. “Expectations and Reality: A Case Study of Return Migration from the United States to Southern Italy.” International Migration Review 8 (2): 245–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/019791837400800210

- Chabé-Ferret, B., J. Machado, and J. Wahba. 2018. “Remigration Intentions and Migrants’ Behavior.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 68: 56–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2017.10.018

- Davids, T., and M. V. Houte. 2008. “Remigration, Development and Mixed Embeddedness: An Agenda for Qualitative Research?”

- Djajić, S., and R. Milbourne. 1988. “A General Equilibrium Model of Guest-Worker Migration: The Source-Country Perspective.” Journal of International Economics 25 (3-4): 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1996(88)90059-1

- Erdal, M. B., and C. Oeppen. 2018. “Forced to Leave? The Discursive and Analytical Significance of Describing Migration as Forced and Voluntary.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (6): 981–998.

- Foley, L., and N. Piper. 2021. “Returning Home Empty Handed: Examining how COVID-19 Exacerbates the non-Payment of Temporary Migrant Workers’ Wages.” Global Social Policy 21 (3): 468–489. https://doi.org/10.1177/14680181211012958

- Ghani, S., and N. A. Morgandi. 2023. “Return Migration and Labour Market Outcomes in South Asia: A CGE Exploration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (20): 5153–5168. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2024.2268965

- Gmelch, G. 1980. “Return Migration.” Annual Review of Anthropology 9 (1): 135–159. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.09.100180.001031

- Katz, E., and O. Stark. 1987. “International Migration Under Asymmetric Information.” The Economic Journal 97 (387): 718–726. https://doi.org/10.2307/2232932

- Khan, A., and H. Arokkiaraj. 2021. “Challenges of Reverse Migration in India: A Comparative Study of Internal and International Migrant Workers in the Post-COVID Economy.” Comparative Migration Studies 9 (1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-021-00260-2

- King, R., and K. Kuschminder. 2022. “Introduction: Definitions, Typologies and Theories of Return Migration.” In Handbook of Return Migration, 1–22. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Kunuroglu, F., F. Van de Vijver, and K. Yagmur. 2016. “Return Migration.” Online Readings in Psychology and Culture 8 (2). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1143

- Limani, D., and J.-L. Arcand. 2023. “Remembrances of Things Past: Evidence from a Twenty-Year Kerala Panel.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (20): 5305–5321. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2024.2268994

- Martinez-Bravo, M., and A. Stegmann. 2022. “In Vaccines we Trust? The Effects of the CIA’s Vaccine Ruse on Immunization in Pakistan.” Journal of the European Economic Association 20 (1): 150–186. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvab018

- Mia, M. A., and M. D. Griffiths. 2020. “The Economic and Mental Health Costs of COVID-19 to Immigrants.” Journal of Psychiatric Research 128: 23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.06.003

- NDTV. 2023. “Kerala State With Surplus Oxygen Amid Mounting COVID Crisis.” Accessed on February 23, 2023 https://www.ndtv.com/kerala-news/kerala-state-with-surplus-oxygen-amid-mounting-covid-crisis-2421039.

- OHCHR. 1990. “International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families.” Technical Report. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

- Opiniano, J., and A. Ang. 2023. “Should I Stay or Should I go? Analyzing Returnee Overseas Filipino Workers’ Reintegration Measures Given the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (20): 5281–5304. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2024.2268992

- Press Trust of India. 2021. “India Received $87 Billion in Remittances in 2021: World Bank”.

- Rahman, Md Mizanur, Sabnam Sarmin Luna, Pranav Raj. 2023. “Disgraceful Return: Gulf Migration and Shifting National Narratives Amid COVID-19.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (20): 5238–5258. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2024.2268987

- Rajan, S. I. 2020. “Migrants at a Crossroads: COVID-19 and Challenges to Migration.” Migration and Development 9 (3): 323–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2020.1826201

- Rajan, S. I., and C. S. Akhil. 2022. “Non-payment of Wages among Gulf Returnees in the First Wave of COVID 19.” In India Migration Report 2022: Health Professionals Migration, edited by S. I. Rajan, 244–263. Delhi: Routledge India.

- Rajan, S. I., and J.-L. Arcand. 2023. “COVID-19 Return Migration Phenomena: Experiences from South and Southeast Asia.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (20): 5133–5152. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2024.2268963

- Rajan, S. I., and H. Arokkiaraj. 2022. “Return Migration from the Gulf Region to India Amidst COVID-19.” In Migration and Pandemics: Spaces of Solidarity and Spaces of Exception, 207–225. Cham: Springer.

- Rajan, S. I., and B. Pattath. 2021. “Kerala Return Emigrant Survey 2021: What Next for Return Migrants of Kerala.” Centre for Development Studies Working Paper No. 504. Thiruvanantharpuam, Kerala.

- Rajan, S. I., and B. Pattath. 2022a. “Distress Return Migration Amid COVID-19: Kerala’s Response.” Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 31 (2): 176–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/01171968221115259

- Rajan, S. I., and B. Pattath. 2022b. “What Next for the COVID-19 Return Emigrants? Findings from the Kerala Return Emigrant Survey 2021.” In India Migration Report 2021, edited by S. I. Rajan, 1st ed., 181–195. London: Routledge India.

- Rajan, S. I., and B. Pattath. 2023. “COVID-19 Led Return Migration from the Gulf-India Migration Corridor.” In International Migration, COVID-19, and Environmental Sustainability (Contributions to Conflict Management, Peace Economics and Development, Vol. 32), edited by M. Chatterji, U. Luterbacher, V. Fert, and B. Chen, 31–46. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Rajan, S. I., B. D. Sami, and S. I. Rajan. 2017. “Tamil Nadu Migration Survey 2015.” Economic and Political Weekly, 85–94.

- Reed, A. E., and L. L. Carstensen. 2012. “The Theory Behind the age-Related Positivity Effect.” Frontiers in Psychology 3: 30180.

- ReliefWeb. 2023. “Management of COVID-19 Pandemic in Kerala Through the Lens of State Capacity and Clientelism.” Accessed February 23, 2023. https://reliefweb.int/report/india/management-covid-19-pandemic-kerala-through-lens-state-capacity 2023.

- Research, PRS Legislative. 2023. “Tamil Nadu Government’s Response to COVID-19.” Accessed February 23, 2023. https://prsindia.org/theprsblog/tamil-nadu-government/T1/textquoterights-response-to-covid-19?page=34&per-page=12023.

- Sasikumar, S. K., and R. Thimothy. 2015. From India to the Gulf Region: Exploring Links Between Labour Markets, Skills and the Migration Cycle. GDC Country Office Nepal, GIZ.

- Shah, N. M., and L. Alkazi. 2023. “COVID-19 and Threats to Irregular Migrants in Kuwait and the Gulf.” International Migration 61 (2): 138–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12992

- Shujaat, Farooq, and G. M. Arif. 2023. “The Facts of Return Migration in the Wake of COVID-19: A Policy Framework for Reintegration of Pakistani Workers.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (20): 5190–5218. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2024.2268976

- Wahba, J. 2021. Who Benefits from Return Migration to Developing Countries? IZA World of Labor.

- Weeraratne, B. 2023. “COVID-19 Pandemic Induced Wage Theft: Evidence from Sri Lankan Migrant Workers.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (20): 5259–5280. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2024.2268989

- Wolff, F. C. 2015. “Do the Return Intentions of French Migrants Affect Their Transfer Behaviour?” The Journal of Development Studies 51 (10): 1358–1373. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2015.1046443

- World Bank Group. 2020. “COVID-19 Crisis Through a Migration Lens,” Technical Report 2020.

- Zachariah, K. C., E. T. Mathew, and S. Irudaya Rajan. 2001a. “Impact of Migration on Kerala's Economy and Society.” International Migration 39 (1): 63–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2435.00135

- Zachariah, K. C., E. T. Mathew, and S. Irudaya Rajan. 2001b. “Social, Economic and Demographic Consequences of Migration in Kerala.” International Migration 39 (2): 43–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2435.00149