Abstract

Objective: To develop cases of preference-sensitive care and analyze the individualized cost-effectiveness of respecting patient preference compared to guidelines.

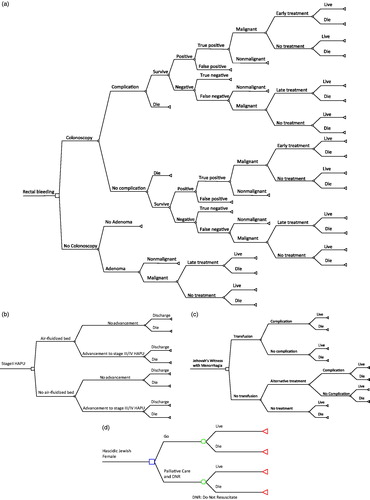

Methods: Four cases were analyzed comparing patient preference to guidelines: (a) high-risk cancer patient preferring to forgo colonoscopy; (b) decubitus patient preferring to forgo air-fluidized bed use; (c) anemic patient preferring to forgo transfusion; (d) end-of-life patient requesting all resuscitative measures. Decision trees were modeled to analyze cost-effectiveness of alternative treatments that respect preference compared to guidelines in USD per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) at a $100,000/QALY willingness-to-pay threshold from patient, provider and societal perspectives.

Results: Forgoing colonoscopy dominates colonoscopy from patient, provider, and societal perspectives. Forgoing transfusion and air-fluidized bed are cost-effective from all three perspectives. Palliative care is cost-effective from provider and societal perspectives, but not from the patient perspective.

Conclusion: Prioritizing incorporation of patient preferences within guidelines holds good value and should be prioritized when developing new guidelines.

Introduction

Providers are challenged on a daily basis with using practice-based guidelines to treat their patients. These guidelines are typically effective and efficient clinical and management protocols developed by providers to improve population health. Such protocols are often implemented as checklists or electronic-based notificationsCitation1. Guidelines sometimes include caveats that do not apply to every situation and, therefore, necessitate clinical judgmentCitation2. As healthcare delivery systems and providers face increasing financial risk for performance on quality measures in the wake of the Affordable Care Act into entities such as accountable care organizations (ACOs)Citation3, providers will be held increasingly accountable to following guidelines when caring for patients. As ACOs begin to monitor provider adherence to guidelines, it will become increasingly important to study how well providers attend to hospitalized patient preferences that run contrary to guideline implementation but still achieve improved outcomes.

Providers do not always use guidelines, but, if they do, departures from guidelines are often viewed as errors. Yet, some departures occur because providers are accommodating patient preferences. Departures resulting from patient preferences are not well studied in medical literatureCitation4. There are many circumstances in which patient preferences do not align with guidelines. Respecting patient preferences can generate a clinical dilemma, as many guidelines do not include protocols for discussing other treatment optionsCitation5,Citation6. Operating outside of guidelines can have variable results, ranging from worsening health status or mortality to potentially better outcomes attributable to patient-centered careCitation7. According to Veroff et al.Citation8, regardless of the outcome, the patient typically gains utility for having personal preferences met.

Guidelines are believed to hold good value based upon their impact on a population. However, depending on the perspective and individual situations, value and efficiency vary. This study uses individualized cost-effectiveness analysis to assess value of preference-sensitive care that departs from guidelinesCitation9. We hypothesize that patient-centered approaches to implementing guidelines are cost-effective at a willingness-to-pay (WTP) of $100,000/QALY from patient, provider, and US societal perspectives. The exception to this hypothesis is when guidelines prevent the occurrence of undesirable outcomes.

Methods

Departure from guidelines in favor of respecting patient preferences was modeled in four unique cases. These hypothetical cases were based on actual patient encounters observed by providers at an urban, tertiary care academic medical center. In each case, patient decision-making occurred at a moment when diagnostics, protocol management, or procedural management were to be administered. Cost-effectiveness analyses were performed to compare the value of guidelines vs the alternative treatment protocol that respected patient preference.

Study design

Decision trees were constructed to analyze the individual cost-effectiveness of guidelines vs patient preference-driven treatment based on an approach described by Ioannidis and GarberCitation9. Treatment protocol that respected patient preference was determined using a patient-centered approach in combination with alternative treatment protocols outlined in existing literature. Each model had a 1-year time horizon. The primary outcome measure of these analyses was the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) in terms of cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) at a WTP threshold of $100,000/QALY. All costs were measured in terms of 2015 US dollars (2015 USD)Citation10. All calculations were performed in Microsoft Excel.

The analyses were conducted from patient, provider, and US societal perspectives. In calculating societal costs and effectiveness, all health outcomes and changes in resource use caused during alternative treatments were considered. Costs presented in the literature were identified as being from either provider or societal perspectives, and were accordingly used in our calculations (). When estimating the cost to patients, the average sum of patient co-pays and deductibles for an insured patient in the US was used to inform an upper-limit of $1,300 in out-of-pocket costsCitation11. This study incorporated patient’s lifetime expectancy for measuring QALYs in all three perspectives. Basic life expectancy of 83 years was used. Costs and probabilities were extracted from the literature. Health utilities for each patient were derived from EQ-5D index scoresCitation12. Univariate sensitivity analyses were conducted on parameters with the greatest uncertainty in the model, this was judged based on previously published ranges of values, or because values were based on assumptions. Base-case inputs and ranges are summarized in , and details of parameter measures appear in the Supplemental Technical Appendix.

Table 1. Model parameters: costs (2015 USD).

Table 2. Model parameters: probabilities.

Table 3. Model parameters: health utilities.

Case 1: Forgo colonoscopy

Case

A 61-year-old, underweight African American male was admitted through the emergency department for evaluation of unexplained weight loss. He had a significant weight loss of 30 pounds in the last year and a maternal family history of colon cancer. The patient, reluctant to be examined, agreed to submit stool samples. Two of the three tests were positive for the presence of occult blood. During a quickly arranged follow-up visit, the patient denied gross blood in stool, but he did admit to chronic constipation and a thinning in stool caliber. The physical exam noted pale conjunctiva, cachexia, and firmness of the general abdomen. A CT scan of the abdomen with contrast demonstrated some descending colonic narrowing and regional lymphadenopathy. The patient preferred not to undergo colonoscopy given improved bowel movements since switching to a prune juice and psyllium-rich diet.

Model

The colonoscopy strategy considered the possibility of proceeding complications (). A colonoscopy was considered positive if polyps were discovered. A true positive indicated the presence of an adenomatous polyp; a false positive indicated a non-adenomatous polyp. If the patient did have an adenomatous polyp, and if this polyp was malignant, they were assumed to undergo early treatment for cancer. If the colonoscopy was negative, and the physician missed an adenomatous polyp (false negative) that was cancerous, the patient was assumed to undergo late treatment as the cancer would not be detected until a more advanced stage. If the patient had an adenocarcinoma and refused colonoscopy, he underwent late treatment, as diagnosis was made at a more advanced disease stage.

Figure 1. Decision tree models. (a) Case 1: Forgo colonoscopy; (b) Case 2: Forgo air-fluidized bed; (c) Case 3: Forgo transfusion; (d) Case 4: Forgo palliative care. DNR, do not resuscitate.

Figure 2. Cost-effectiveness plane of incremental cost-effectiveness ratios for each case, stratified by patient, provider, and societal perspectives, relative to a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100,000/QALY (not to scale). Decisions to forgo transfusion and colonoscopy are cost-effective from all perspectives, as well as the decision to forgo palliative care and DNR [do not resuscitate] from the patient perspective. All other cases and perspectives are of low value.

![Figure 2. Cost-effectiveness plane of incremental cost-effectiveness ratios for each case, stratified by patient, provider, and societal perspectives, relative to a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100,000/QALY (not to scale). Decisions to forgo transfusion and colonoscopy are cost-effective from all perspectives, as well as the decision to forgo palliative care and DNR [do not resuscitate] from the patient perspective. All other cases and perspectives are of low value.](/cms/asset/98b8eb48-e7b8-40fb-8464-f395f8703bc6/ijme_a_1254091_f0002_b.jpg)

Uncertainty

We evaluated the uncertainty around the probability of complication during colonoscopy. The literature suggests that the probability of complication can be as low as 0.09% or as high as 0.3%Citation13.

Case 2: Forgo air-fluidized bed

Case

This is the case of a 55-year-old woman with a body-mass index (BMI) over 40 who was in post-operative care for a coronary-artery bypass graft (CABG). Prior to her hospitalization, she was wheelchair-bound for 15 years due to deteriorating health and uncomfortable walking. The CABG went well but, following surgical recovery, she began complaining about pains in her legs and lower back. Nurses performing a routine skin exam discovered non-blanchable redness on her sacrum and deep bruising on her heels, although no open wounds were noted. Given her immobility, nurses ordered an air-fluidized bed to reduce risk for pressure ulcer (PrU) development. However, the patient preferred a traditional hospital bed, noting that the air fluidized bed during a prior hospitalization was uncomfortable and kept her from sleeping well.

Model

This case models an air-fluidized bed order vs alternative protocol that allows for a patient to use a traditional hospital bed despite high risk for pressure ulcer development (). In the air-fluidized bed strategy, a 55-year-old patient with a stage II PrU accepts all International Guidelines for PrU treatment and preventionCitation14. These guidelines include: skin check and risk assessment every 12 h; repositioning from side-to-side every 3 h; managing moisture and incontinence; nutritional management; and use of modern support surfaces (e.g. air-fluidized bed). In the case of an alternative protocol that respects the patient’s desire to have a traditional hospital bed, the patient received all other practice guidelines and was repositioned side-to-side twice as frequently, thus requiring more nursing time. Despite repositioning, the patient was still at increased risk for PrU progression to stages III or IV.

Uncertainty

We evaluated uncertainty around the probability of advancing to a stage III/IV PrU when using the air-fluidized bed. The probability of advancing can be as low as 0.0497 or as high as 0.067 ()Citation15. We also evaluated uncertainty around the probability of advancing to stage III/IV when refusing the air-fluidized bed. Here, the probability of advancing ranged from 0.198–0.267Citation15.

Additionally, we tested the two-way sensitivity of disutility for hospitalization and PrU incidence under the condition that the patient’s preference was honored; in this case, they were in a preferred state so the outcome could be somewhat preferential (+0.03 QALYs). The utility of hospitalization with a new bed order was simultaneously reduced since the patient would presumably sleep worse than without the bed, −0.03 QALYs ().

Case 3: Forgo transfusion

Case

A 44-year-old female, self-identifying as a Jehovah’s Witness, was admitted for worsening weakness with onset menorrhagia. A laboratory workup determined that she was profoundly anemic with a hemoglobin (Hgb) level of 2.5 g/dL. Her management was complicated given religious observances that called for abstention from any blood productsCitation16. She had similar episodes in the past, but none were quite as severe.

Model

This model was derived on the assumption that guidelines favor transfusion over alternative treatments in order to stabilize patients (). In both arms, the aim of care was to stabilize the patient until they could undergo surgery for fibroids or a hysterectomy. However, surgery, and other interventions that would have been applied to both situations, were not included in the model as they would cause no difference in the relative outcomes between the two branches. Assuming one transfusion raised hemoglobin levels by 3 g/dL, the patient would receive three transfusions in order to raise her hemoglobin to a minimum value sufficient for interventional surgery, 11 g/dL. One of the most serious complications of transfusion was transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI). TRALI was assumed to be the sole complication in this model; hemolytic transfusion reaction is another potentially lethal complication, but considered too rare for a decision model. Treatment alternatives included administration of hydroxyethyl starch, Darbepoetin, ferric gluconate, and uterine artery embolization (UAE). Hydroxyethyl starch would be administered every 30 min until a sufficiently stable blood pressure was attained; assuming this took 3 h, she would receive six units. The provider would administer 200 μg darbepoetin weekly for 3 weeks and a 60-h course of 125 mg ferric gluconate would be given every hour. Complication following alternative treatment considered adverse events associated with darbepoetin/ferric gluconate and a UAE.

Uncertainty

We evaluated the uncertainty of health utility in this patient if, despite her preferences, a provider gave her a life-saving blood transfusion. While survival has a high utility (e.g. 0.8 QALYs), her personal preferences may weight her health state low (e.g. −0.3 QALYs) to represent her dissatisfaction to live against her religious beliefs and prolonged anxiety.

Case 4: Forgo palliative care

Case

A 95-year old Hasidic female presented with multiple chronic conditions, including: chronic kidney disease; coronary artery disease with a history of four CABGs; congestive systolic and diastolic heart failure with an ejection fraction of 15%; insulin dependent diabetes; and peripheral vascular disease requiring both bilateral ileofemoral bypass grafts as well as a right leg amputation below the knee. She was admitted 2 months prior following a cardiac arrest and her hospital course included two more cardiac arrests that were successfully coded. The new resident on service re-addressed goals of care with her primary caregiver. The caregiver recognized the minimal likelihood of the patient ever leaving the hospital in better or similar health as to when she was admitted. However, given the patient’s devout belief that includes the preciousness of life at all costs, an aggressive care plan was preferred.

Model

Guidelines would encourage the patient’s family to consider a palliative care approach including pain management and do not resuscitate (DNR) orders in case of arrest given her low likelihood of recovery (). The patient’s preference directs the model along the resuscitate branch, which had only a slight chance of survival compared to DNR.

Uncertainty

We evaluated the uncertainty around the probability of survival following resuscitation. Among those greater than 90, survival ranged from 0.032–0.073Citation17. We also performed a two-way sensitivity analysis of preferences for living with or without the palliative care approach by varying QALYs ±25%; an increased utility for living without palliative care could be as high as 0.5 QALYs, and a decreased utility for living with the palliative care and DNR approach could be as low as 0.3 QALYs.

Results

ICERs presented in summarize the results of the cost-effectiveness analysis. The results portray varying levels of cost-effectiveness from a WTP threshold of $100,000/QALY (). Controlling for the patient, provider, and societal perspectives of each model highlights variation in the value of each case.

Table 4. Results of cost-effectiveness analysis comparing evidence-based practices to patient preferences in four cases.

Case 1: Forgo colonoscopy

Respecting preferences to forgo colonoscopy generated no clinically meaningful change in effectiveness (18.175 QALYs) vs receiving colonoscopy (18.174 QALYs). In all three perspectives, undergoing colonoscopy produced a greater expected cost than not undergoing colonoscopy. Thus, respecting patient preference dominated colonoscopy in all three perspectives, since it was less costly at the same relative effectiveness.

Case 2: Forgo air-fluidized bed

The use of an air-fluidized bed yielded greater expected effectiveness per hospitalization (16.293 QALYs) than an adjusted care approach (16.158 QALYs). From the patient perspective, inclusion of the air-fluidized bed generated no difference in expected costs per hospitalization, since costs exceeded the out-of-pocket maximum of $1,300. From the provider and societal perspectives, expected costs were greater for an adjusted care approach than with adherence to EBPs. In all three perspectives, use of the air-fluidized bed resulted in cost-savings and increased effectiveness. Therefore, guidelines dominated accommodation of patient preferences.

Case 3: Forgo transfusion

Undergoing alternative treatment yielded 31.034 QALYs, whereas receiving a transfusion yielded 21.722 QALYs. In all three perspectives, undergoing the alternative treatment resulted in greater cost-per-hospitalization than undergoing transfusion. Each ICER was less than $100,000/QALY, and are, therefore, considered cost-effective alternatives to blood transfusion in this patient’s case.

Case 4: Forgo palliative care

In all three perspectives, palliative care and DNR orders resulted in no QALY generation as the patient did not survive, nor were any additional costs incurred. Resuscitation yielded an incremental effectiveness of 0.019 QALYs. The expected cost of resuscitation was greater in all three perspectives. ICERs for resuscitation varied. From the patient perspective, resuscitation was cost-effective given her personal preference for sustained life. However, from the provider and societal perspectives, palliative care was the cost-effective approach, since resuscitation exceeded an ICER of $100,000/QALY.

Sensitivity and threshold analyses

We performed sensitivity and threshold analyses for variables where the literature specified a range, or for variables where assumptions were made. These uncertainties were applied to each perspective. Variation in all input values used in the protocol respecting a patient’s desire to forgo colonoscopy did not change results.

The ICER for an alternative protocol allowing for traditional bed use varied based on small changes in the utility of patient preference for a new bed. From the patient perspective, alternative protocol generated increased QALYs and was cost-effective, as the QALYs of a new bed scenario were reduced.

For transfusion abstention, varying the utility of survival post-transfusion changed the results in all three perspectives. At a value of 0.796 QALYs, transfusion would deliver greater effectiveness than abstention, making transfusion the dominant strategy.

In the palliative care case, varying the probability of survival following resuscitation changed the ICER from the patient perspective. At a rate of survival less than 3.62%, the ICER for resuscitation exceeded $100,000/QALY. The ICER was not sensitive to changes in QALYs based on preference for resuscitation.

Discussion

The individualized cost-effectiveness of guidelines to preferred alternatives that respect patient preference varied depending on both the case and the perspective (i.e. patient, provider, or US societal). For the colonoscopy case, effectiveness for each branch was equal; however, respecting the preference to forgo colonoscopy generated cost-savings that led to this approach dominating guidelines in all three perspectives. In the high-risk PrU case, accepting the air-fluidized bed resulted in greater effectiveness than embracing patient preference. From all perspectives, the cost of alternative protocol allowing for traditional bed use was equal or greater than the cost of implementing guidelines. Thus, guidelines dominate patient preference in the case of the high-risk PrU patient, although these results are sensitive to some variance in QALYs. For the transfusion case, embracing patient preference was more costly, but provided greater effectiveness from each perspective. These outcomes suggest that alternatives to transfusion could be cost-effective. In the resuscitation case, patient preference for all life saving measures was more expensive and generated only marginal gains in effectiveness except for the patient perspective, where the ICER was below $100,000/QALY. From the hospital and societal perspectives, DNR was the cost-effective alternative.

Providers in primary and specialty care face difficult decisions like these in order to balance stringent guideline adherence with patient preferences. Respecting patient preference can redirect a patient off of guidelines, placing providers in a vulnerable situation, since they are consciously making such changes rather than committing an error. Guidelines typically reference population data to generate cost-effective recommendations at the societal-level. Consequently, guidelines are inherently limited at delivering individually cost-effective decisions when considering the circumstances of each patient or providerCitation18. The results of these individualized cost-effectiveness analyses provide insight with respect to operating outside of guidelines. This leaves open the question of whether guidelines that fail to incorporate patient preferences are truly the best standard of care. If respecting patient preferences leads to improved health, then there is the dual benefit of greater utility and patient satisfaction.

These results also illustrate that patients can make economical decisions about procedural management of their care while maximizing the value of their out-of-pocket deductibleCitation19. For preferences leading to more expensive care, insured patients rarely feel the extent of financial burden beyond $1,300 for an incremental gain in QALYs. The incremental effectiveness gained from an alternative treatment that maximizes out-of-pocket expenses would only need to be greater than 0.013 QALYs in order to be cost-effective at the specified WTP threshold. Increased effectiveness above this margin could arguably yield clinically meaningful changes in the patient’s quality-of-life as well.

Limitations

This study is limited by several factors. First, these cases use population health data, and are not necessarily the results of individual patients. Second, data used to guide probabilities and costs were acquired from existing literature including randomized controlled trials; thus, some cited studies were limited in their sample size and generalizability. Third, since health utilities did not explicitly exist for each case, we estimated these utilities based on nationally representative EQ-5D index scores. These index scores did not necessarily vary by perspective, except where assumptions were made about a range of preferences. Occasionally, proxy EQ-5D scores were used when given chronic conditions were not valued in the existing literature (i.e. the disutility of an acquired foot deformity was used for “below knee amputation” as reported in the literature).

Implications

This study is meant to highlight the value of shared decision-making to providers, patients, and policy-makers. Shared decision-making is a tool for balancing evidence-based practice with patient autonomy without incurring inferior clinical results. Additionally, this study further erodes the 21st-century provider’s autonomy, since evidence-based medicine has given providers the semblance of scientific reasoning for asserting increased influence over medical management decisions. Despite a complicated decision-making process, this study highlights that increased patient input can be cost-effective, even without considerations of financial incentives from the Affordable Care Act such as reimbursement policies that influence providers’ decisions at the health-system level.

In response to these findings, medical education needs to continue embracing shared decision-making as a crux of quality improvement. Providers who are well trained in shared decision-making should be supported for accommodating patient preferences, even when it results in care not explicit in guidelines. Presently, healthcare places higher value on the individuality of patient care, and guidelines do not always meet the needs and autonomy of certain individualsCitation20. As these results show, not all guidelines are cost-effective depending on the individual circumstances of the patient. Thus, providers would benefit from a system that stratifies patient cases by those where guidelines are feasible, or alternative approaches are necessary.

Given the opportunity to redesign elements of healthcare delivery systems in the wake of the Affordable Care Act, there should be consideration for allowing providers to deliver care based on patient autonomy. A partial antidote of incorporating patient autonomy into clinical practice could be to increase patient engagement in the development of guidelines. Guidelines should also reflect patients’ decision-making process with decision nodes and refusal guidelines rather than fixed care pathways. The next generation of care guidelines must become more prescriptive, in that these guidelines will expand to consider alternative care pathways that respect patient preference. Creation of such prescriptive guidelines will not necessarily require extensive research or development of new strategies, but rather a return to next best practices and adaptive problem-solving that is already witnessed in a hospitalized setting lacking the resources necessary to follow guidelinesCitation21. In the case of a patient at high risk for pressure ulcer development who prefers a traditional hospital bed, prescriptive guidelines would outline the use of more frequent turning and changing of bed sheets to reduce ulcer development. In the case of a patient who forgoes a medically indicated colonoscopy, prescriptive guidelines might suggest fecal immunochemical testing, which has higher detection rates for colorectal cancer than fecal occult blood test, followed by re-assessment of patient attitudes in light of these mores sensitive test resultsCitation22.

As health systems continue to gather data on clinical processes and patient outcomes from EHRs, providers should have the ability to indicate cases where departure from guidelines are taken. These departures should be stratified by the belief that guidelines would not benefit the patient or are at odds with patient preferences. Especially in the case of the latter, health systems will have to recognize that a provider’s departure from protocol can be justified and is not a consequence of ignorance or error. The measures of quality and performance given to providers by important stakeholders of performance bodies such as CMS, The Joint Commission, or an ACO should be scaled not only by guideline adherence or patient outcomes, but by the provider’s ability to accommodate patient preferences and increase satisfaction. An ordinal scale would transform efficiency of the current system where medical errors are perceived as dichotomousCitation23, and providers are burdened with the cost of unavoidable adverse eventsCitation24.

Conclusions

The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) has made the topic of patient-centered care a funding priority, but does not support the use of economic evaluation to study outcomesCitation25. This study highlights that patient-centered care does hold good value from most perspectives (i.e. patient, provider, and societal), and that patient utility strongly influences value from the patient perspectiveCitation26. We believe that, given these results, it will have a strong impact on the PCORI community and have influence on the Methods Committee’s current dilemma of a lacking endorsement for economic evaluation in conjunction with patient-centered outcomes researchCitation25,Citation27.

Ultimately, extensive investigation will be required to support current efforts of customizing guidelines for patient-centeredness. Working in a complex system of healthcare delivery with providers and patients makes it prone to human error, as well as opportunities where non-standardized approaches succeed for select patients that do not fit an obvious moldCitation28. In cases where patients vocalize their own preferences for care that are not economically or medically beneficial, the medical community must ensure appropriate education and disclosure of the risks and benefits pertaining to the various care options. This conversation should be carried out with the knowledge that, ultimately, the physician should defer to the patient’s wishes.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This manuscript was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Rockville, MD, USA.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

WVP and ADW were the recipients of an AHRQ T32 National Research Service Award (5 T32 HS000078-17), which was sponsored by David Meltzer at The University of Chicago. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Technical Appendix

Download MS Word (21.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The Authors wish to thank the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality for providing WVP, ADW and DOM with financial support from a T32 award to explore this research topic.

References

- Pronovost PJ, Vohr E. Safe patients, smart hospitals: how one doctor's checklist can help us change health care from the inside out. New York, NY: Penguin, 2010

- Mold JW, Gregory ME. Best practices research. Fam Med 2003;35:131-4

- Fisher ES, McClellan MB, Safran DG. Building the path to accountable care. N Engl J Med 2011;365:2445-7

- Bingham SL. Refusal of treatment and decision-making capacity. Nurs Ethics 2012;19:167-72

- Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Crump RT. Decision support for patients: values clarification and preference elicitation. MCRR 2013;70(1 Suppl):50s-79s

- Padula WV, Wald HM, Makic HM. Pressure ulcer risk pssessment and prevention. Ann Intern Med 2013;159:718

- Meterko M, Wright S, Lin H, et al. Mortality among patients with acute myocardial infarction: the influences of patient-centered care and evidence-based medicine. Health Serv Res 2010;45:1188-204

- Veroff D, Marr A, Wennberg DE. Enhanced support for shared decision making reduced costs of care for patients with preference-sensitive conditions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:285-93

- Ioannidis JP, Garber AM. Individualized cost-effectiveness analysis. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1001058

- Consumer Price Index. May 2007 National occupational employment and wage estimates. In: U.S. Department of Labor, editor. Washington DC: Bureau of Labor Statistics Division of Occupational Employment Statistics, 2007

- Claxton G, Rae M, Panchal N, et al. Health benefits in 2014: stability in premiums and coverage for employer-sponsored plans. Health Affairs 2014;33:1851-60

- Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan V. Preference-based EQ-5D index scores for chronic conditions in the United States. Med Decis Making 2006;26:410-20

- Hur C, Chung DC, Schoen RE, et al. The management of small polyps found by virtual colonoscopy: results of a decision analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract Je Am Gastroenterol Assoc 2007;5:237-44

- Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: clinical practice guideline. Washington, DC: National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP), 2014. http://www.npuap.org/resources/educational-and-clinical-resources/prevention-and-treatment-of-pressure-ulcers-clinical-practice-guideline/. Accessed May 15, 2015

- Sullivan PW, Lawrence WF, Ghushchyan V. A national catalog of preference-based scores for chronic conditions in the United States. Med Care 2005;43:736-49

- West JM. Ethical issues in the care of Jehovah's Witnesses. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2014;27:170-6

- Menon PR, Ehlenbach WJ, Ford DW, et al. Multiple in-hospital resuscitation efforts in the elderly. Crit Care Med 2014;42:108-17

- Basu A, Meltzer D. Value of information on preference heterogeneity and individualized care. Medical Decision Making 2007;27:112-27

- Meltzer DO. Accounting for future costs in medical cost-effectiveness analysis. J Health Econ 1997;16:33-64

- Meltzer DO. Hospitalists and the doctor-patient relationship. J Legal Studies 2001;30:589-606

- Padula WV, Gibbons RD, Pronovost PJ, et al. Using clinical data to predict high-cost performance coding issues associated with pressure ulcers: a multilevel cohort model. JAMIA 2016; [Epub ahead of print, August 18, 2016]

- Jensen CD, Corley DA, Quinn VP, et al. Fecal immunochemical test program performance over 4 rounds of annual screening: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2016;164:456-63

- Armstrong BG, Sloan M. Ordinal regression models for epidemiologic data. Am J Epidemiol 1989;129:191-204

- Phillips RL, Jr., Bartholomew LA, Dovey SM, et al. Learning from malpractice claims about negligent, adverse events in primary care in the United States. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13:121-26

- Messner DA, Towse A, Mohr P, et al. The future of comparative effectiveness and relative efficacy of drugs: an international perspective. J Comp Eff Res 2015;4:419-27

- Frank L, Basch E, Selby JV. The PCORI perspective on patient-centered outcomes research. JAMA 2014;312:1513-14

- Methodology Committee of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). Methodological standards and patient-centeredness in comparative effectiveness research: the PCORI perspective. JAMA 2012;307:1636-40

- Padula WV, Duffy MP, Yilmaz T, et al. Integrating systems engineering practice with health-care delivery. Health Syst 2014;3:159-64

- Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Van Ballegooijen M, Zauber AG, et al. Effect of rising chemotherapy costs on the cost savings of colorectal cancer screening. J National Cancer Inst 2009;101:1412-22

- Padula WV, Mishra MK, Makic MB, et al. Improving the quality of pressure ulcer care with prevention: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Med Care 2011;49:385-92

- Forbes JM, Anderson MD, Anderson GF, et al. Blood transfusion costs: a multicenter study. Transfusion 1991;31:318-23

- Cox CE, Carson SS, Govert JA, et al. An Economic evaluation of prolonged mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med 2007;35:1918-27

- Warren BB, Durieux ME. Hydroxyethyl starch: safe or not? Anesth Analg 1997;84:206-12

- Kong CY, Meng L, Omer ZB, et al. MRI-guided focused ultrasound surgery for uterine fibroid treatment: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Am J Roentgenol 2014;203:361-71

- Pizzi LT, Bunz TJ, Coyne DW, et al. Ferric gluconate treatment provides cost savings in patients with high ferritin and low transferrin saturation. Kidney Int 2008;74:1588-95

- Powell J, Gurk-Turner C. Darbepoetin alfa (Aranesp). Proceedings (Baylor University Medical Center). 2002;15:332-5

- Sznajder M, Aegerter P, Launois R, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of stays in intensive care units. Intensive Care Med 2001;27:146-53

- The Dartmouth Atlas. Inpatient spending per decedent during the last six months of life, by gender and level of care intensity. Lebanon, NH: Trustees of Dartmouth, 2015. http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/data/table.aspx?ind=102&loc=2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11&loct =2&fmt =127&ch =9,32. Accessed July 20, 2016

- Pickhardt PJ, Choi JR, Hwang I, et al. Computed tomographic virtual colonoscopy to screen for colorectal neoplasia in asymptomatic adults. N Engl J Med 2003;349:2191-200

- Shaw JW, Johnson JA, Coons SJ. US valuation of the EQ-5D health states: development and testing of the D1 valuation model. Med Care 2005;43:203-20