Abstract

Aims: To better understand the impact of the clinical course of multiple sclerosis (MS) and disability on employment, absenteeism, and related factors.

Materials and methods: This study included respondents to the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis Registry spring 2015 update survey who were US or Canadian residents, aged 18–65 years and reported having relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), secondary progressive MS (SPMS), or primary progressive MS (PPMS). The RRMS and SPMS participants were combined to form the relapsing-onset MS (RMS) group and compared with the PPMS group regarding employment status, absenteeism, and disability. Multivariable logistic regression was used to examine the relationship between employment-related outcomes and factors that may affect these relationships.

Results: Of the 8004 survey respondents, 5887 (73.6%) were 18–65 years of age. The PPMS group (n = 344) had a higher proportion of males and older mean age at the time of the survey and at time of diagnosis than the RMS group (n = 4829). Female sex, age, age at diagnosis, cognitive and hand function impairment, fatigue, higher disability levels, ≥3 comorbidities, and a diagnosis of PPMS were associated with not working. After adjustment for disability, the employed PPMS sub-group reported similar levels of absenteeism to the employed RMS sub-group.

Limitations: Limitations of the study include self-report of information and the possibility that participants may not fully represent the working-age MS population.

Conclusions: In MS, employment status and absenteeism are negatively affected by disability, cognitive impairment, and fatigue. These findings underscore the need for therapies that prevent disability progression and other symptoms that negatively affect productivity in persons with MS to enable them to persist in the workforce.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, incurable disease of the central nervous system that causes symptoms such as fatigue and progressive impairment in many domains, including physical functioning and cognition. Diagnosis typically occurs between the ages of 20–40 years, when most people are of working age. Approximately 85% are diagnosed with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), which usually progresses over many years to a secondary progressive phase (SPMS); collectively, RRMS and SPMS can be referred to as relapsing-onset MS (RMS). The remaining 10–15% of persons with MS have a progressive course at onset without the usual relapsing phaseCitation1. Although there are multiple Food and Drug Administration–approved treatments for relapsing forms of MS, there are currently none for primary progressive MS (PPMS), and all clinical trials in this population, except oneCitation2, have been unsuccessful. Early interventions that slow disease progression could potentially benefit maintaining employment.

The adverse effects of MS on employment are substantial, with unemployment rates of 40–80% across various levels of disabilityCitation3–9. The loss of employment, voluntarily or involuntarily, is associated with older age, female sex, greater financial security, and disability levelCitation6,Citation10–15. A recent review by Schiavolin et al.Citation9 shows that studies conducted on employment status after 2006 have included a majority of RRMS patients or do not have the MS clinical course noted in their study. Understanding whether these factors affect those with PPMS similarly as those with RMS is important to consider when identifying strategies to maintain employment, such as vocational rehabilitation programs. Vocational rehabilitation may offer a means to help persons with MS stay in the workforce, although the success rate is generally not as high as that for other populations receiving this rehabilitationCitation16.

For those who remain employed, challenges such as presenteeism and absenteeism can occur. In one study, employees with MS missed 4-times more work days in a 1-year period compared with control employeesCitation17. In the CLIMB (Comprehensive Longitudinal Investigation of Multiple Sclerosis at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital) study, 14% of working patients with a clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) or RRMS reported absenteeism, with a mean of 4% of work time lostCitation18. The investigators found no statistically significant relationship between absenteeism and cognition on the Symbol Digit Modalities Test or between absenteeism and fatigue (Modified Fatigue Impact Scale), quality of life ([QoL]; MSQOL-54, SF-36), depression (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale), or anxiety (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults). However, this could be due in part to only a small proportion of patients reporting absenteeism. Also, information on the effects of overall disability, cognition, fatigue, hand function, and sociodemographic factors on absenteeism in working-age persons with MS is limited and comes primarily from RMS populations. Studies that have evaluated absenteeism in PPMS have been small; of these, only one was conducted in the USCitation6,Citation19,Citation20.

The objective of this study was to describe and compare factors associated with employment and absenteeism in participants of the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) Registry between those with a PPMS clinical course and those with an RMS clinical course to identify potential differences.

Methods

NARCOMS Registry

The NARCOMS Registry is a voluntary self-report registry for persons with MS that began in 1996 under the auspices of the Consortium of MS CentersCitation21. Participants enroll by submitting a completed questionnaire either online or by mail. After enrollment, participants are asked to update their information by completing surveys semiannually, on paper or online as per their preference. This study was limited to registry participants who completed the spring 2015 update survey, resided in the US or Canada, were of the traditional working age (18–65 years), and reported a clinical course of RMS or PPMS.

The institutional review board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham approves the NARCOMS Registry and its projects. Registry participants gave written informed consent for their de-identified information to be used for research purposes.

Employment/absenteeism

Registry participants were asked to indicate whether they were employed (yes, full time; yes, part time; or no) in the past 6 months and the number of hours worked per week, if employed (<20, 20–30, 31–35, 36–40, or >40). For this analysis, the questions were considered together to create two employment categories: (1) employment (employed/not working) for those who reported any hours worked (employed) and those who reported no hours worked (not working); and (2) employment status (full time/part time), where those employed full time reported working >35 hours per week and those employed part time reported working <35 hours per week. Absenteeism was evaluated by asking participants whether MS had caused them to cut back on the number of hours worked in the past 6 months (yes/no) or to miss any work days in the past 6 months (yes/no). For those who reported missing work days, the number of days missed in the past 6 months was also collected.

Clinical and demographic characteristics

Disability was measured using the Patient Determined Disease Steps (PDDS). The PDDS is a validated measure that correlates highly with the physician-scored Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS)Citation22. Similar to the EDSS, the PDDS emphasizes mobility. It is scored ordinally from 0 (normal) to 8 (bedridden), for which a score of 0 approximates an EDSS score of 0, a score of 3 approximates an EDSS score of 4.0–4.5 and represents early gait disability without the need for an assistive device, and scores of 4, 5, and 6 represent EDSS scores of 6–6.5. The Performance Scales (PS) are single items used to measure the level of symptom disability in eight domains, including cognition, fatigue, and hand function (CPS, FPS, HPS, respectively), and have adequate convergent and divergent validityCitation23–25. Participants rated their cognitive, fatigue, and hand function status as one of six levels of disability: 0 (normal), 1 (minimal), 2 (mild), 3 (moderate), 4 (severe), or 5 (total disability).

Survey participants reported information such as their date of birth, year of diagnosis, race, and level of education at enrollment. The spring 2015 update survey included questions pertaining to the clinical course of the MS, worsening of symptoms, annual income, marital status, and disability benefits. Education categories were <12 years, high school diploma, associate’s degree or technical degree, bachelor’s degree, and postgraduate degree. Participants reported their current clinical course of MS from the following choices: CIS, RRMS, SPMS, PPMS, progressive-relapsing MS, don’t know, or other. Only those with RRMS, SPMS, and PPMS were included in this analysis. Symptom worsening was assessed using the question: “Over the last 6 months, have your MS symptoms worsened in a gradual, progressive manner (not due to relapses or exacerbations)?” with response choices of yes, no, or unsure. Occurrence of a relapse in the past 6 months that was treated with a corticosteroid was assessed using two questions on whether the participant had a relapse in the past 6 months (yes, no, or unsure) and how many relapses were treated with a corticosteroid (0–6). Those participants who responded that they had a relapse and one or more were treated with a corticosteroid were considered to have a relapse. Annual income was reported as < $15,000; $15,001–$30,000; $30,001–$50,000; $50,001–$100,000; > $100,000, or I do not wish to answer. Marital status was indicated as never married, married, divorced, widowed, separated, or cohabitating/domestic partner. The spring 2015 update survey asked NARCOMS participants to report various comorbid conditions (presence/absence) using the following question format: “Has a doctor ever told you that you have …?”Citation26. Individual comorbidities (in parentheses) were grouped into the following categories: vascular (high cholesterol, hypertension, heart trouble, diabetes), autoimmune (thyroid), gastrointestinal (irritable bowel disease), cancer, musculoskeletal (osteoporosis, fibromyalgia), and other (lung trouble, sleep apnea, migraines), as described previouslyCitation27, and to be consistent with other MS studiesCitation28,Citation29. Participants were asked whether they received disability benefits such as Social Security or private disability insurance (yes/no).

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized using frequencies (percentages) and mean (SDs). Comparisons between groups, responders vs non-responders and RMS vs PPMS cohorts, were based on Chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables.

The association of being employed and employment status with the PDDS and clinical course of MS, RMS vs PPMS, was evaluated using Chi-square tests. The association of absenteeism, for those cutting back hours and missing work days in the past 6 months, with disability and clinical course of MS was evaluated using nominal logistic regression. Similarly, the association of disability and clinical course of MS with receiving disability benefits was evaluated using nominal logistic regression.

To evaluate the association of multiple demographic and clinical factors with employment status, absenteeism, and receiving disability benefits, multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted separately for each of these outcomes. The models investigating absenteeism were restricted to those who reported working more than 35 hours per week. The demographic and clinical characteristics considered for these models included sex, race (white or nonwhite), education (less than bachelor’s degree or bachelor’s degree or higher), marital status (married and cohabitating/domestic partner or not married), annual income, age at the time of the survey, age at diagnosis, whether a relapse treated with a steroid occurred in the past 6 months (yes/no), number of comorbidity categories, PDDS, CPS, FPS, and HPS. For the PDDS, participants were classified as having mild (0–2), moderate (3–4), or severe (5–8) disabilityCitation30. The CPS, FPS, and HPS were classified as normal (0), mild impairment (1–2), or moderate-to-severe impairment (3–5). The number of comorbidity categories per respondent was categorized as 0, 1, 2, or ≥3. The covariates were evaluated using a forward stepwise procedure with a minimum corrected Akaike information criterion used as the entrance criterion; PDDS and clinical course were forced into the model. Goodness of fit was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test and the discriminating ability of the model was described using c-statistics. Some factors were required to be retained in the model, including sex, age, PDDS group, clinical course of MS, and age at diagnosis.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study cohort

The overall response rate for the NARCOMS spring 2015 update survey was 74.0% (n = 8,004 participants of 10,816 invited). Compared with respondents, non-respondents were more likely to be younger (mean [SD] age = 55.4 [11.7] vs 58.8 [10.3] years; p < .0001), with a shorter disease duration at the time of the update (17.1 [10.4] vs 20.1 [9.9] years; p < .0001), and were less likely to be white (87.8% vs 92.1%; p < .0001). The majority of respondents (99.8%) were residents of the US or Canada. After restriction of the sample to respondents aged 18–65 years, 5,887 respondents (73.6%) were retained. Of those aged 18–65 years, 5,173 reported a clinical course of RMS or PPMS. Demographic and clinical characteristics of all working-age respondents combined, as well as the RMS (n = 4,829) and PPMS (n = 344) groups separately, are presented in . The PPMS group had a lower proportion of females and was more severely disabled and older at the time of the survey and at diagnosis (all p < .0001).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics overall and by clinical course of MS.

Employment and disability

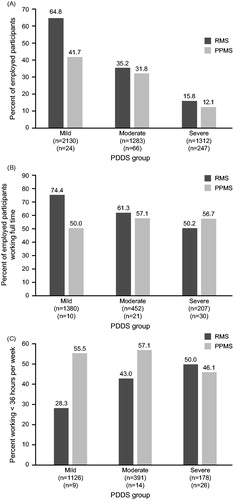

The proportion of respondents employed in the RMS group was higher compared with the PPMS group (43.1% vs 18.1%, respectively; ). Also, the proportion of respondents employed full time was higher for the RMS group (69.1% vs 55.7%, respectively; ). The association of disability (PDDS) with employment showed that, as expected, respondents with mild PDDS levels were more likely to be employed than those with severe PDDS levels (64.5% vs 15.2%, respectively, χ12 = 81.4, p < .0001; ). Age, sex, age at diagnosis, number of comorbidity categories, MS clinical course, FPS, HPS, CPS, and PDDS were included in the final multivariable logistic regression model for being employed. After adjusting for these factors, the PPMS group was no longer an independent predictor of being employed (p = .0507). The odds of not working were associated with older age, younger age at diagnosis, male sex, and higher levels of cognition, fatigue, hand function, and overall disease severity ().

Figure 1. Proportion of participants employed (A) and proportion of employed participants working more than 35 hours per week (B) by PDDS group and clinical course of MS (C). PDDS: Patient Determined Disease Steps; PPMS: primary progressive multiple sclerosis; RMS: relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis/secondary progressive multiple sclerosis.

Table 2. Employment proportions for each clinical course of MS.

Table 3. Employment (employed vs not working) multivariable logistic regression modelTable Footnotea.

For those employed, 74.2% of RMS and 51.1% of PPMS participants reported working more than 35 hours per week. In the RMS group, respondents with mild PDDS levels were more likely to be working more than 35 hours per week than those with severe PDDS levels (χ12 = 937.8, p < .0001; ). Age, sex, age at diagnosis, number of comorbidity categories, MS clinical course, FPS, HPS, and PDDS were included in the final multivariable logistic regression model for factors being associated with working more than 35 hours per week. Similar to employment, after adjusting for these factors, the PPMS group was no longer an independent predictor of being employed (p = .6374). The odds of working more than 35 hours per week were associated with younger age, older age at diagnosis, male sex, not having three or more comorbidities, no fatigue, and mild disability (PDDS) compared to severe PDDS levels ().

Table 4. Multivariable logistic regression modelTable Footnotea for the odds of working more than 35 hours per week compared to those working less than 35 hours per week.

Table 5. Absenteeism (cut back hours and missed work days) assessed using multivariable logistic regression models for those employed.

Absenteeism

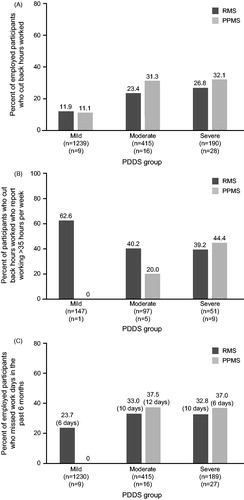

The proportion of participants reporting cutting back on hours worked was higher in the moderate and severe PDDS groups than in the mild PDDS group (). There was no significant difference between RMS and PPMS groups on hours cut back (16.0% vs 28.3%); however, results did differ by disability level, being lower for those with mild disability compared with those with moderate (odds ratio (95% confidence interval) [OR (95% CI)] = 2.25 (1.698–2.969), p = .031) or severe disability (OR (95% CI) = 2.72 (1.922–3.859), p = .0004). Of the participants with RMS who cut back their hours, 62.6% of those with mild disability were still working more than 35 hours per week compared with 40.2% and 39.2% of those with moderate or severe disability, respectively ().

Figure 2. Proportion of employed participants who have cut back hours worked (A), proportion of employed participants who have cut back hours worked in past 6 months who reported working more than 35 hours per week (B), and proportion of employed participants who missed work days in the past 6 months, with mean number of work days missed shown in parentheses (C), by PDDS group and clinical course of MS. PDDS: Patient Determined Disease Steps; PPMS: primary progressive multiple sclerosis; RMS: relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis/secondary progressive multiple sclerosis.

In addition to reduced hours, missed work days are another important aspect of absenteeism. Again, there was no significant difference between the proportion of participants reporting missed work days in the RMS (26.6%) and PPMS (30.8%) groups (χ12 = 0.4389, p = .5076). However, a lower proportion of participants in the mild PDDS group (RMS, 23.7% and PPMS, 0%) reported missed work days compared with those in the moderate (RMS, 33.0% and PPMS, 37.5%) and severe (RMS, 32.8% and PPMS, 37.0%) PDDS levels. A greater number of work days missed in the last 6 months was seen at higher PDDS disability levels for RMS (mild, mean = 6.0 days; moderate = 10.0 days; severe = 11.7 days; ) in those still employed. The PPMS group had more variability in the mean number of days missed. In the multivariable model, older age, having three or more comorbidities compared to none, and moderate-to-severe impairment in cognition, fatigue, and hand function were associated with increased odds of absenteeism ().

Disability

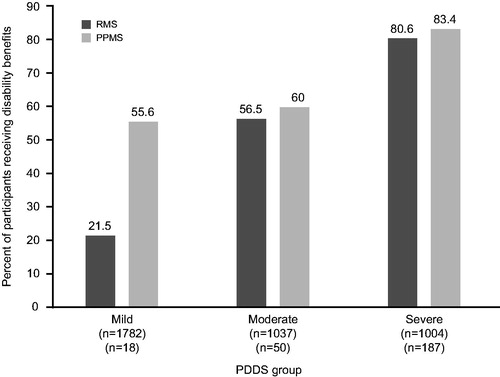

Almost half (48.5%) of respondents reported receiving disability benefits at the time of the survey (RMS, 46.5%; PPMS, 76.9%). Of those receiving benefits, a small proportion were employed (12.6%), with most working less than 35 hours per week (81.5%). The odds of receiving disability benefits were higher for those with moderate (OR [95% CI] = 4.16 [3.916–5.440], p = .0141; ) and severe disability (OR [95% CI] = 14.59 [12.097–17.590], p < .0001) compared to those with mild disability, but did not differ between those with RMS and those with PPMS (p = .0512). Age, sex, age at diagnosis, number of comorbidity categories, MS clinical course, FPS, HPS, CPS, and PDDS were included in the final multivariable logistic regression model for receiving disability benefits. The odds of receiving disability benefits were associated with older age, younger age at diagnosis, male sex, having three or more comorbidities compared to none, and moderate-to-severe levels of cognition, fatigue, hand function, and overall disease severity ().

Figure 3. Proportion of participants receiving disability benefits by PDDS group and clinical course of MS. PDDS: Patient Determined Disease Steps; PPMS: primary progressive multiple sclerosis; RMS: relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis/secondary progressive multiple sclerosis.

Table 6. Disability benefits (yes vs no) multivariable logistic regression modela.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated employment and absenteeism in large RMS and PPMS cohorts in the NARCOMS Registry. We found that a lower proportion of working-age PPMS respondents were currently employed compared with RMS respondents, which is explained in part by differences in age between the two groups. However, among those employed, the reported absenteeism was remarkably similar between those with RMS and those with PPMS. Older age, having three or more comorbidities compared to none, and moderate-to-severe impairment of cognition, fatigue, and hand function were consistently associated with an increased risk of absenteeism.

Many of the factors associated with not working, including older age, female sex, younger age at diagnosis, cognitive impairment, fatigue, impaired motor function, and higher disability, are consistent with factors found in other studies in MSCitation6,Citation10–13,Citation31–36. Disability level was strongly associated with employment status, even before the traditional retirement age of 65 years. Bauer et al.Citation31 showed an association between the clinical course of MS and employment, with a higher proportion of patients with relapsing courses being employed vs those with primary or secondary progressive courses. In the present study, we found that respondents in the PPMS group were 2–3-times less likely to be employed than those in the RMS group. The proportion not working reported by our working-age participants was 58.6%, which is similar to the rate reported in Julian et al.Citation3 of 58%, but lower than what was recently found (42.2%) by Van Dijk et al.Citation37 in Australia for 2013. However, neither of these studies examined differences in the clinical course of MS.

We also noted that participants who had three or more categories of comorbidities were more likely to be unemployed, suggesting that a higher burden of illness generally contributes to difficulty maintaining employment. Older persons are more likely to have multiple conditionsCitation38; however, the increased odds of not working when a participant had three or more comorbidities persisted after adjusting for age. Of note, results of a Swedish study suggest that persons with MS who had psychiatric comorbidities were more likely to receive disability benefitsCitation39. While there is strong evidence that education is related to work-related difficulties, there is limited evidence that the level of education is a predictor of unemploymentCitation6,Citation15,Citation40. After controlling for other factors, we did not find that the level of education was associated with not working, potentially due to the larger sample size associated with this study.

More than three-quarters of PPMS working-age respondents were receiving disability payments, with the majority reporting part-time employment. Not surprisingly, as the PDDS levels increased, the proportion of respondents receiving disability benefits increased. As observed in other studiesCitation17,Citation18, we found that almost one-quarter of working-age persons with MS reported absenteeism. Participants with moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment or moderate-to-severe fatigue were consistently at an increased risk of absenteeism, an effect that persisted even after adjusting for disability level as measured by the PDDS, which reflects mainly mobility. Similarly, Glanz et al.Citation18 found univariate relationships between absenteeism and fatigue, as well as anxiety and physical and mental QoL, although no factors were found to be statistically significant in multivariable analyses. In our study, after adjusting for disability, the PPMS group retaining employment reported similar numbers of missed days and reduced hours as those in the employed RMS group, thus demonstrating the potential for productive employment, regardless of the type of MS. At mild and moderate PDDS levels, the PPMS group was more likely than the RMS group to report working of 35 hours or less, which may reflect a pre-emptive practical adjustment to accommodate changes in symptoms, medical appointments, or burden of additional comorbiditiesCitation17.

Limitations of this work include self-reporting of information pertaining to absenteeism, disability, and comorbidities by participants. However, participants were familiar with these questions because they are routinely asked in the semiannual update surveys. Self-reported disability and comorbidity instruments have been validated previouslyCitation22–24,Citation26. In addition to evaluating differences between different types of MS, we were able to consider a range of disability levels and domains of impairment other than mobility. NARCOMS participants may not fully represent the working-age MS population; although we restricted the analysis to those aged 18–65 years, we were still able to retain a sufficient number of respondents in each MS clinical course category. Other information that was not collected from participants was the nature of employment and the necessity to maintain employment vs having the option to elect to work. Although the nature of employment and the ability to elect to work have rarely been considered in other studies, they likely do have an effect on employment status. Although the negative impact of informal caregiving on work productivity has been demonstrated and may be an important consideration in participants with MSCitation41, it was not assessed in this study. The cross-sectional nature of this study did not allow for us to assess causal relationships.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that the clinical course of MS has a significant impact on employment status, with a greater proportion of PPMS participants reporting unemployment compared with RMS participants, after adjusting for various factors, including disability levels. Cognition, fatigue, and hand function emerged as having strong associations with employment status, regardless of the clinical course of MS, and this reinforces the role that rehabilitation interventions can play in this area. Although reports on physical QoL overall were lower in the PPMS than RMS group, both the physical and mental aspects of QoL were closely associated with levels of absenteeism in both groups. Although the direction of these relationships cannot be determined based on this analysis, these results highlight the need for patient-centered approaches to enhance job retention, job satisfaction, and work productivity among people with MS.

Future research could use a longitudinal design to examine how to help persons with MS stay in the workforce and maintain productivity, and to identify differences in job retention between those with PPMS and those with SPMS. Further studies are necessary to assess the potential impact of the nature of job functions, working environment, disease-modifying therapies, and symptomatic medications on sustaining employment.

Regardless of the course of MS, there is an unmet need to treat symptoms and prevent disability to optimize participation in the workforce.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

NARCOMS is a project of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC). NARCOMS is funded in part by the CMSC and the Foundation of the CMSC. Additional funding for this project was provided by Genentech, Inc.

Declaration of financial/other interests

NPT is an employee of Genentech. GC has served on data and safety monitoring boards for AMO Pharma, Apotek, Biogen-Idec, GlaxoSmithKline, Gilead, Horizon, Modigenetech/Prolor, Merck, Opko, Neuren, Sanofi, Teva, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (protocol review committee), and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (OPRU oversight committee) and consulting or advisory boards for Cerespir, Consortium of MS Centers, D3, Genzyme, Genentech, Innate Therapeutics, Janssen, Klein-Buendel, MedImmune, Medday, Novartis, Opexa Therapeutics, Receptos, Roche, Savara, Spiniflex, Somahlution, Teva, Transparency Life Sciences, and TG Therapeutics. RAM receives research funding from Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Research Manitoba, Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada, Multiple Sclerosis Scientific Foundation, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, Rx & D Health Research Foundation, the Waugh Family Chair in Multiple Sclerosis, and Crohn’s and Colitis Canada, and has conducted clinical trials funded by Sanofi. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Previous presentation

Some data contained in this paper were presented as poster presentations at the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy and Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers meetings in 2016.

Acknowledgments

Third-party writing support for this manuscript was provided by Health Interactions, Inc., and Articulate Science LLC, and funded by Genentech, Inc. This study was funded in part by Genentech, Inc. Copyright for cognition, fatigue and hand function Performance Scales (Registration Number/Date: TXu000743629/1996-04-04) assigned to DeltaQuest Foundation, Inc., effective October 1, 2005. US copyright law governs terms of use.

References

- Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet 2002;359:1221-31

- Montalban X, Hauser SL, Kappos L, et al. Ocrelizumab versus placebo in primary progressive multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2016 Dec 21. [Epub ahead of print]

- Julian LJ, Vollmer T, Mohr DC. Exiting and re-entering the work force. J Neurol 2008;255:1354-1360

- Moore P, Harding KE, Clarkson H, et al. Demographic and clinical factors associated with changes in employment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2013;19:1647-54

- Pompeii LA, Moon SD, McCrory DC. Measures of physical and cognitive function and work status among individuals with multiple sclerosis: a review of the literature. J Occup Rehabil 2005;15:69-84

- Bøe Lunde HM, Telstad W, Grytten N, et al. Employment among patients with multiple sclerosis—a population study. PLoS One 2014;9:e103317

- Kobelt G, Berg J, Lindgren P, et al. Costs and quality of life of patients with multiple sclerosis in Europe. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006;77:918-26

- Kobelt G, Berg J, Atherly D, et al. Costs and quality of life in multiple sclerosis: A cross-sectional study in the United States. Neurology 2006;66:1696-1702

- Schiavolin S, Leonardi M, Giovannetti AM, et al. Factors related to difficulties with employment in patients with multiple sclerosis: a review of 2002–2011 literature. Int J Rehabil Res 2013;36:105-111

- Larocca N, Kalb R, Scheinberg L, et al. Factors associated with unemployment of patients with multiple sclerosis. J Chronic Dis 1985;38:203-10

- Kornblith AB, La Rocca NG, Baum HM. Employment in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Int J Rehabil Res 1986;9:155-65

- Roessler RT, Fitzgerald SM, Rumrill PD, et al. Determinants of employment status among people with multiple sclerosis. Rehabil Couns Bull 2001;45:31-39

- Edgley K, Sullivan MJ, Dehoux E. A survey of multiple sclerosis: II. Determinants of employment status. Can J Rehabil 1991;4:127-32

- Roessler RT, Rumrill PD Jr, Li J, et al. Predictors of differential employment statuses of adults with multiple sclerosis. J Vocat Rehabil 2015;42:141-152

- Raggi A, Covelli V, Schiavolin S, et al. Work-related problems in multiple sclerosis: a literature review on its associates and determinants. Disabil Rehabil 2016;38:936-44

- Chiu C-Y, Chan F, Bishop M, et al. State vocational rehabilitation services and employment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J 2013;19:1655-64

- Ivanova JI, Birnbaum HG, Samuels S, et al. The cost of disability and medically related absenteeism among employees with multiple sclerosis in the US. Pharmacoeconomics 2009;27:681-91

- Glanz BI, Degano IR, Rintell DJ, et al. Work productivity in relapsing multiple sclerosis: associations with disability, depression, fatigue, anxiety, cognition, and health-related quality of life. Value Health 2012;15:1029-35

- O’Connor RJ, Cano SJ, Ramió i Torrentà L, et al. Factors influencing work retention for people with multiple sclerosis: cross-sectional studies using qualitative and quantitative methods. J Neurol 2005;252:892-6

- Smith MM, Arnett PA. Factors related to employment status changes in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2005;11:602-9

- The Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC). http://www.mscare.org/?page=about_the_cmsc. Accessed November 4, 2015

- Learmonth YC, Motl RW, Sandroff BM, et al. Validation of patient determined disease steps (PDDS) scale scores in persons with multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol 2013;13:37

- Schwartz CE, Vollmer T, Lee H. Reliability and validity of two self-report measures of impairment and disability for MS. Neurology 1999;52:63

- Marrie R, Goldman M. Validity of performance scales for disability. Mult Scler 2007;13:1176-82

- Marrie RA, Cutter G, Tyry T, et al. Validation of the NARCOMS Registry: fatigue assessment. Mult Scler 2005;11:583-4

- Horton M, Rudick RA, Hara-Cleaver C, et al. Methods in neuroepidemiology validation of a self-report comorbidity questionnaire for multiple sclerosis. Neuroepidemiology 2010;35:83-90

- Marrie RA, Horwitz R, Cutter G, et al. Comorbidity delays diagnosis and increases disability at diagnosis in MS. Neurology 2009;72:117-24

- Tettey P, Simpson S, Taylor BV, et al. Vascular comorbidities in the onset and progression of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 2014;347:23-33

- Moccia M, Lanzillo R, Palladino R, et al. The Framingham cardiovascular risk score in multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol 2015;22:1176-83

- Marrie RA, Cutter G, Tyry T, et al. Does multiple sclerosis-associated disability differ between races? Neurology 2006;66:1235-40

- Bauer HJ, Firnhaber W, Winkler W. Prognostic criteria in multiple sclerosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1965;122:542-51

- Mitchell JN. Multiple sclerosis and the prospects for employment. J Soc Occup Med 1981;31:134-8

- Roessler RT, Rumrill PD, Fitzgerald SM. Predictors of employment status for people with multiple sclerosis. Rehabil Couns Bull 2004;47:96-103

- Rao SM, Leo GJ, Ellington L, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: II. Impact on employment and social functioning. Neurology 1991;41:692-6

- Cadden M, Arnett P. Factors associated with employment status in individuals with multiple sclerosis cognition, fatigue, and motor function. Int J MS Care 2015;17:284-91

- Dyck I, Jongbloed L. Women with multiple sclerosis and employment issues: a focus on social and institutional environments. Can J Occup Ther 2000;67:337-46

- Van Dijk PA, Kirk-Brown AK, Taylor B, et al. Closing the gap: Longitudinal changes in employment for Australians with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J 2016 Nov 24. [Epub ahead of print]

- van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Metsemakers JFM, et al. Multimorbidity in general practice: prevalence, incidence, and determinants of co-occurring chronic and recurrent diseases. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:367-75

- Tinghög P, Björkenstam C, Carstensen J, et al. Co-morbidities increase the risk of disability pension among MS patients: a population-based nationwide cohort study. BMC Neurol 2014;14:117

- Busche KD, Fisk JD, Murray TJ, et al. Short term predictors of unemployment in multiple sclerosis patients. Can J Neurol Sci 2003;30:137-42

- McKenzie T, Quig ME, Tyry T, et al. Care partners and multiple sclerosis: differential impact on men and wormen. Int J MS Care 2015;17:253-60