Abstract

Aim: To evaluate nuclear imaging center attributes that cardiologists and primary care physicians (PCPs) consider when referring patients for single-photon emission computed tomography myocardial perfusion imaging (SPECT-MPI) tests, and how these attributes impact physician referral decisions in the United States.

Methods: A targeted literature review and seven one-to-one interviews with physicians and imaging center directors were conducted to identify attributes that could impact physicians’ referral decisions. The impact of the identified attributes was assessed via an online discrete choice survey among eligible PCPs and cardiologists randomly selected from a nationally representative panel, and quantified with an odds ratio (OR) scale estimated with a multivariable logistic regression.

Results: Nine two-level attributes were identified: ease of the referral process, waiting time for tests, insurance preauthorization assistance, time to receive results, conclusive test reports, patient satisfaction, a protocol for rapid conversion from an exercise to a pharmacological stress test, patient communication, and assistance with parking/wheelchair access. A total of 410 physicians, including 208 (50.7%) cardiologists and 202 (49.3%) PCPs completed the survey. Among all physicians, a protocol that allows for a rapid conversion from an exercise to a pharmacological stress test (OR = 2.9) and preauthorization assistance (OR = 2.6) were the most impactful attributes. Additionally, cardiologists preferred imaging centers that provide an easy referral process (OR = 2.7), while PCPs favored centers offering a conclusive test report (OR = 2.4).

Limitations: Some center features that might impact physician referral decision were not evaluated in this study, if they were not easily changeable from an imaging center’s perspective.

Conclusions: The availability of a protocol for rapid conversion from an exercise to a pharmacological stress test and preauthorization assistance had the most significant impact on physician referral decisions for SPECT-MPI. Additionally, cardiologists preferred centers providing an easy referral process, while PCPs favored those offering a concluding statement and actionable steps in test reports.

Introduction

The most common type of cardiovascular disease is coronary artery disease (CAD), a complex disorder characterized by occluded or reduced blood flow within the arteries that perfuse the heartCitation1. Manifestations of CAD include atherosclerosis, ischemia, angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, and sudden cardiac deathCitation2. Non-invasive assessment of myocardial perfusion plays an important role in the detection, management, and prognosis of CADCitation3. Single-photon emission computed tomography myocardial perfusion imaging (SPECT-MPI) is a non-invasive technique that measures the relative differences in myocardial blood flow to detect blockage in coronary arteries, a hallmark of CADCitation4. During SPECT-MPI, a radioactive perfusion tracer is administered to the patient, and the coronary arteries are imaged in three dimensions while the patient is at rest and during physical (exercise) or pharmacologic (e.g. vasodilators or dobutamine) stressCitation5. Studies have shown that SPECT-MPI is highly accurate in detecting the location and extent of ischemiaCitation6,Citation7, leading to its wide adoption for the diagnosis of CAD.

SPECT-MPI is available in a range of healthcare facilities; thus, physicians are likely to have multiple options when referring patients for this imaging testCitation8. These facilities include cardiologists’ private offices, affiliated hospitals, and independent nuclear imaging centers or labs, and may differ substantially in how they schedule and perform tests, communicate findings, and support physician referrals. Improving the patient experience of care, reducing healthcare costs, and improving population-level health are three interdependent goals (the “Triple Aim”) for elevating the overall quality of the US healthcare systemCitation9. Extensive knowledge of ways to improve site-specific patient care and better allocate resources presents an opportunity to further these aims. Thus, it is important for nuclear imaging centers to have a thorough understanding of which attributes physicians consider when referring patients to SPECT-MPI tests and how these attributes impact their referral decisions.

To date, few studies have evaluated the impact of nuclear imaging center attributes on physician referral patterns. While other studies have provided general discussion on strategies for imaging centers or radiology departments to improve services and increase referralsCitation10,Citation11, none have quantified how center attributes affect physicians’ decision-making during the referral process for SPECT-MPI tests. To address this gap in the literature, this study evaluated which attributes of nuclear imaging centers cardiologists and primary care physicians (PCPs) consider when referring patients for SPECT-MPI, and to what extent these attributes impact physician referrals in US clinical practice.

Methods

This survey study was a conjoint analysis designed to: (1) identify important attributes of nuclear imaging centers that physicians consider when referring patients; and (2) quantify the impact of these attributes on physician referrals. To identify important center attributes and associated levels (i.e. alternative characteristics of the attribute) of nuclear imaging centers, a literature review and one-to-one phone interviews of eligible physicians and imaging center directors were conducted. Then, to evaluate the impact of identified center attributes, the study used a discrete choice experiment (DCE) approach via an online survey.

Literature review and interviews

First, a search on PubMed and on the grey literature (including reports, working papers, government documents, white papers, and evaluations produced by organizations outside of the traditional commercial or academic publishing and distribution channels) was performed to identify an initial list of center attributes and their levels. The initial list consisted of center attributes regarding accessibility, responsiveness, quality, stress agents, imaging modalities, and patient experience. This initial list was discussed with five physicians (three cardiologists and two PCPs) and two imaging center directors who were randomly selected from nationally representative panels and had agreed to have a one-on-one phone interview. During the interview, each participating director or physician was asked to rank the importance of each attribute from the initial list and comment on the levels of each attribute they consider to be important. The list of center attributes and their levels for use in the survey study were finalized based on feedback and opinions from these discussions.

Study population

Physicians were eligible to participate in the survey study if they: (1) were a cardiologist or a PCP; (2) had more than three years of practice in the US; and (3) had treated at least 10 patients in need of a SPECT-MPI test in the three months preceding the survey. Cardiologists and PCPs who participated in the study were recruited via an existing US physician panel managed by a professional survey vendor. Based on a checklist for conjoint analysis developed by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes ResearchCitation12, the rule of thumb for the sample size decision is at least 300, with a minimum of 200 respondents per group for subgroup analysisCitation13. This recommended sample size is supported by literature describing and using DCE methodologyCitation12–16. Therefore, a total of 200 cardiologists and 200 PCPs were targeted for recruitment in this study. Data was de-identified to maintain participant anonymity. This study was granted an exemption from institutional review by the New England Institutional Review Board on 28 April 2016.

Conjoint analysis and discrete choice experiment methodology

Conjoint analysis is a scientific discriminating statistical technique used to elicit individual preference and has been applied to healthcare researchCitation17. It is based on the premise that a product or service can be described by a number of attributes, and the extent to which an individual values a product or service depends on the level of these attributesCitation18. DCE is a commonly used approach in conjoint analysis studies to capture individuals’ preference for product or service attributes through realistic, hypothetical scenarios. DCE allows for the quantification of the relative importance of different attributes, the trade-offs between different levels of attributes, and is a valuable approach for physician or patient-centered evaluations of health technologiesCitation19.

Study questionnaire design

An online physician survey questionnaire using DCE methodology was developed based on the center attributes and levels derived from the literature search and interviews with physicians and center directors. The questionnaire included screening questions to confirm physician eligibility, questions about the physicians’ background and experience with SPECT-MPI, a tutorial explaining the study process and selected imaging center attributes, and choice cards to assess participating physicians’ preferences for alternative center profiles for referral.

Each choice card included profiles of two hypothetical nuclear imaging centers (i.e. Center A and Center B), generated with random combinations of the levels of each identified attribute. With nine two-level attributes, an orthogonal design of 60 pairs of hypothetical imaging center profiles was adopted based on the DCE approach. Each pair of hypothetical imaging center profiles constituted one choice card. The generated choice cards served as a question bank and were grouped into question sets. Six question sets, each with 10 choice cards, were randomly generated from the 60 choice-card pairs. Together with four additional choice cards for validity tests, each participating physician was presented with a total of 14 choice cards in the survey. When making a choice, physicians were instructed to assume that patients to be referred had insurance coverage, the test was not urgently needed, and distances from patients to the two hypothetical centers under consideration were of similar distances from patients.

Each participating physician was presented with one randomly selected question set from the question bank and asked to select the preferred hypothetical imaging center on each choice card. Four additional choice cards were added to each question set to test response validity and consistency. These included test–retest and transitivity questions.

Survey launch and data collection

First, a series of pilot tests with three physicians (two cardiologists and one PCP) were conducted via a video conferencing tool (WebEx) to ensure the logic and clarity of the questionnaire. During each pilot test, a moderator went through the questionnaire with the participant and documented and addressed questions and concerns. The questionnaire was then revised based on this feedback. Second, a limited launch of the online survey was conducted in approximately 10% of the targeted sample. Results of the limited launch were reviewed to ensure that the physicians understood the questions and that their answers were logical. After confirming its clarity and logic, the online survey was fully launched among physicians randomly sampled from the physician panel that was geographically representative of the US. The results of the surveys were de-identified and collected via an online portal.

Data analysis

An analytical data set was created following the online data collection. Characteristics of participating physicians and their practices were described with counts and percentages for categorical variables and with means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables. Multivariable analyses using a logistic model were conducted to analyze physician preferences between alternative center profiles. In each choice card, the preference between two hypothetical imaging centers was regressed on the differences in attribute levels. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated based on the model coefficients, which indicated the relative impact of a center attribute on physician preference. An OR greater than one for an attribute indicated that physicians preferred a profile with that attribute level to the alternative level when making referrals, assuming all other center attributes remained unchanged. A p-value of ≤.05 indicated whether the impact of an attribute was statistically significant. Statistical tests were conducted in SAS 9.3 software.

Results

Center attributes and levels

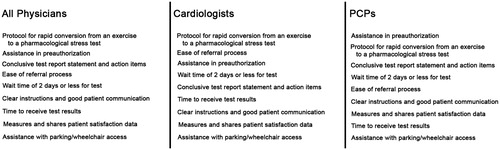

The targeted literature review identified 23 potential attributes of a nuclear imaging center in terms of accessibility, responsiveness, quality, stress agents and imaging modalities, and patient experience (Supplemental Table 1). Based on discussions with interviewed physicians and center directors, a list of nine attributes, each with two levels, was included in the survey. Detailed specifications of these nine center attributes and levels are provided in . These attributes were related to the ease of the referral process, the typical waiting time for the scheduled test, whether assistance in obtaining preauthorization from health insurance was available, the time to receive test results, the availability of a conclusive statement in test reports, patient satisfaction measures and results sharing with referring physicians, the availability of a protocol that allows for a rapid conversion from an exercise to a pharmacological stress test, clear instructions and good communication with patients, and assistance with parking and wheelchair access.

Table 1. Nuclear imaging center attributes and levels included in the survey.

Physician characteristics

Among physicians who were randomly selected and invited to participate via email, a total of 410 eligible physicians, composed of 208 (50.7%) cardiologists and 202 (49.3%) PCPs, completed the survey. describes the characteristics of the participating physicians and their practice. Of the PCPs, 85 (42.1%) were in family or general practice and 117 (57.9%) specialized in internal medicine. The distribution of physician practice region was balanced among the four US census regions, with a higher proportion (31.7% of PCPs and 40.4% of cardiologists) from the Northeast US. On average, PCPs had been in practice longer than cardiologists (mean [SD]: 20.3 [6.8] vs. 17.2 [8.0] years). More PCPs than cardiologists were in private practice (71.3% vs. 47.1%), while more cardiologists than PCPs practiced in academic centers (21.6% vs. 6.9%), community hospitals (16.8% vs. 7.4%), and outpatient departments in a hospital setting (12.0% vs. 7.4%). In addition, 34.6% of cardiologists’ practices were affiliated with imaging centers compared to 10.9% of PCPs’ practices.

Table 2. Summary of physician characteristicsTable Footnotea.

Regarding the average number of patient referrals for SPECT-MPI tests in the three months prior to survey participation, cardiologists referred nearly three times more patients than PCPs (97 vs. 36 patients). When making referral decisions, greater than half of cardiologists (56.7%) usually chose from no more than two centers while most PCPs (44.6%) usually considered three to four centers. However, the majority of cardiologists (86.5%) and PCPs (72.3%) typically used only one or two of these available options ().

Physician preferences

All physicians

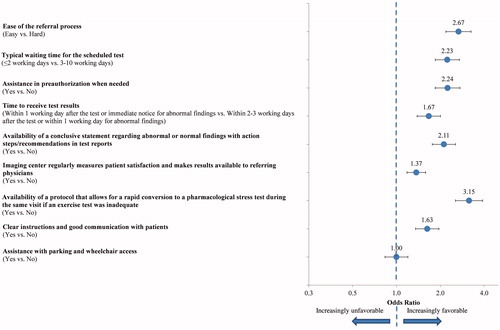

represents the DCE survey results evaluating the impact of the nine selected attributes on referrals among all participating physicians. The ORs of each attribute were statistically significantly greater than one (all p < .001, except for “assistance with parking and wheelchair access” [p = .038]), indicating that centers with the preferred attribute level vs. the alternative level were more likely to be selected by the physicians for SPECT-MPI imaging test referrals. The availability of a protocol that allows for rapid conversion from an exercise to a pharmacological stress test during the same visit if an exercise test was inadequate (OR = 2.87, p < .001) and assistance in obtaining preauthorization from health insurance (OR = 2.57, p < .001) were the most impactful attributes. For example, an imaging center with the availability of a protocol for rapid conversion from an exercise to a pharmacological stress test was associated with a 1.87 higher odds to be chosen by physicians compared to a center without such availability, while holding all other attributes the same.

Figure 1. Physician preferences for attributes of nuclear imaging centers – all physicians. An OR >1.0 (dotted line) for an attribute indicated that physicians preferred a profile with the first listed attribute level to the second listed attribute level when making referrals, assuming other center attributes remained unchanged. All comparisons were statistically significant (all p < .001, with the exception of “assistance without wheelchair access” [p = .038]).

![Figure 1. Physician preferences for attributes of nuclear imaging centers – all physicians. An OR >1.0 (dotted line) for an attribute indicated that physicians preferred a profile with the first listed attribute level to the second listed attribute level when making referrals, assuming other center attributes remained unchanged. All comparisons were statistically significant (all p < .001, with the exception of “assistance without wheelchair access” [p = .038]).](/cms/asset/a8eaabba-2552-40a9-95bf-f47dd1066d63/ijme_a_1314969_f0001_c.jpg)

Other important attributes with ORs greater than two included the availability of a conclusive statement regarding abnormal or normal findings with action steps/recommendations in test reports, an easy referral process, and a waiting time of less than two working days for the scheduled test (all p < .001). The ORs of the attributes regarding clear instructions and good communication with patients, time to receive test results, and the sharing of patient satisfaction measures were around 1.50 (all p < .001), indicating that these were considered to be less impactful on physician referrals compared to attributes with an OR greater than two. Assistance in parking and wheelchair access had the lowest OR (1.14, p = .038) and was considered by physicians to be the least important among the nine attributes considered. The absolute ranking of attributes by OR is presented in .

Cardiologists

Consistent with the trend observed among all physicians, the availability of a protocol that allows for rapid conversion from an exercise to a pharmacological stress test was the most impactful from the cardiologists’ perspective (OR = 3.15, p < .001) (). However, cardiologists ranked the ease of the referral process as the second most important attribute (OR = 2.67, p < .001), and assistance with preauthorization as the third most important attribute (OR = 2.24, p < .001). In addition, assistance in parking/wheelchair access was not found to have an impact on referral decisions by cardiologists (OR = 1.00, p = .993). The rankings of the other attributes were similar to those involving both cardiologists and PCPs ().

Figure 3. Physician preferences for attributes of nuclear imaging centers – cardiologists. An OR ratio >1.0 (dotted line) for an attribute indicated that physicians preferred a profile with the first listed attribute level to the second listed attribute level when making referrals, assuming other center attributes remained unchanged. All comparisons were statistically significant (p < .001), except for “assistance without wheelchair access” (p = .993).

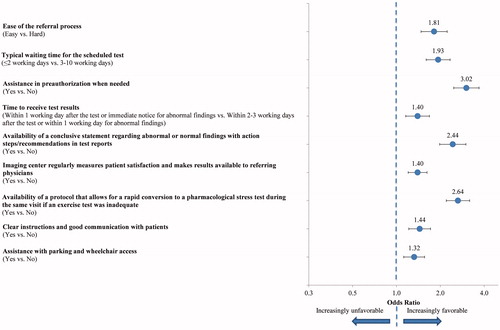

Primary care physicians

Compared to cardiologists who referred more patients for SPECT-MPI, PCPs shared similar preferences on most attributes and had slightly different considerations on some attributes. They most valued assistance in insurance preauthorization when needed and highly preferred centers with that attribute (OR = 3.02, p < .001) (). The availability of a protocol for rapid conversion from an exercise to a pharmacological stress test was also very important (ranked the second most important) to PCPs (OR = 2.64, p < .001). In addition, the availability of a conclusive statement in test reports was the third most important attribute for PCPs (OR = 2.44, p < .001). Differing from cardiologists’ stated preference, PCPs considered assistance in parking and wheelchair access to be somewhat important (OR = 1.32, p < .001), although this was still the lowest ranked attribute. The remaining attributes were ranked in a similar order to those of cardiologists ().

Figure 4. Physician preferences for attributes of nuclear imaging centers – PCPs. Legend: An OR ratio >1.0 (dotted line) for an attribute indicated that physicians preferred a profile with the first listed attribute level to the second listed attribute level when making referrals, assuming other center attributes remained unchanged. All comparisons were statistically significant (p < .001). PCPs: primary care physicians.

Discussion

This study identified nine important attributes of nuclear imaging centers that physicians consider when referring patients for SPECT-MPI tests, and used a DCE approach to quantify how these attributes impact referral decisions. This method has recently been applied in other healthcare scenarios and is considered valuable for evaluations of health products and servicesCitation18,Citation19. The results of the DCE survey in this study were used to generate and rank hypothetical nuclear imaging center profiles, mimicking a real-world setting. In this way, physician preferences for both individual imaging center features and overall imaging center profiles were captured.

Of the nine identified attributes, the availability of a protocol that allows for rapid conversion from an exercise to a pharmacological stress test and assistance in obtaining preauthorization from health insurance were considered to be the most impactful for SPECT-MPI referrals among all physicians. Overall, cardiologists and PCPs displayed consistent preferences on most center attributes including the primary importance of the two mentioned above. However, these two groups of physicians also weighed some attributes differently, which could be taken into consideration by imaging centers serving particular populations of physicians. For instance, cardiologists, who had nearly three times the number of referrals for SPECT-MPI compared to PCPs, considered ease of the referral process to be more important compared to PCPs. Conversely, PCPs indicated that a conclusive statement regarding normal/abnormal findings with recommendations in test reports was more critical than cardiologists. Most cardiologists have frequent exposure to imaging reports and are less likely to need assistance with management decisions given their area of expertise. In addition, PCPs, who generally have an established relationship with patients and tend to have more responsibility for long-term patient care, might be expected to consider patient-centered attributes (e.g. assistance in insurance preauthorization and assistance with parking and wheelchair access) more than cardiologists when making referral decisions.

The findings of the current study are consistent with prior literature regarding the impact of certain imaging center attributes. A study published in 1990 examined physicians’ considerations when making referrals to radiologists and reported that the ability to schedule patients quickly (wait time), personal familiarity with the radiologist, and quickly receiving results were the three most important considerationsCitation20. Similarly, a study conducted in an urban teaching hospital identified three key issues in physician referrals to CT or MRI exams: wait time to get an appointment, scheduling procedures, and communication of findingsCitation21. In addition, a prior survey study on physicians who referred patients to a single, large academic radiology department found that one-third of referring physicians would change service provider if their expectations of scheduling ease were not metCitation22. Ease of the referral process was also identified as an important center attribute physicians would consider in this study. The current study also revealed that assistance in insurance preauthorization was a highly impactful attribute among cardiologists, which had not been evaluated in prior studies. Additionally, a new attribute specific to SPECT-MPI – a protocol for converting from an exercise to a pharmacological stress test – was identified as an important characteristic that physicians consider. Such a protocol is time saving and permits flexibility. This suggests that physicians consider the specific type of imaging test to be performed when evaluating imaging centers for referrals, and that different attributes may be more or less important depending on the referred test.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to quantify how imaging center attributes impact physicians’ decision-making processes during referrals for SPECT-MPI tests. This study ranked the impact of nine center attributes on physician referrals and quantified which attributes were the most important to PCPs versus cardiologists. The quantification of the importance of each attribute also informed degrees of trade-offs that physicians were willing to accept among different significant factors. This assessment provides greater granularity and specificity than prior studies, contributing valuable information on similarities and differences in making referral decisions among these two groups of physicians regarding SPECT-MPI imaging centers. Future studies are encouraged to investigate the impact of different features of imaging centers in physician referrals, perhaps from the perspective of an imaging center director, or to gauge the interest in new radiopharmaceuticalsCitation23 for SPECT-MPI. In addition, as patients move towards greater awareness of their healthcare utilization and costsCitation24, knowledge of attributes most important to the ultimate consumers of imaging tests may further improve the delivery of care.

The results of this study should be interpreted in light of its limitations. Although this study sampled a large group of physicians, the physician panel may not be completely representative of the broader cardiologist and PCP population. Also, more PCPs were found to practice in private practice (71.3%) than cardiologists (47.1%), while more cardiologists were in academic medical centers than PCPs (21.6% vs. 6.9%). Future studies are needed to evaluate center attributes and their impact on referral decisions among cardiologists and PCPs in different practice settings. Additionally, to reduce response burden, only a limited number of features considered to be most impactful were included in the DCE survey. Some center features that might impact referral but were not easily changeable from a center’s perspective (the distance from imaging centers to patients, attributes related to an urgent test, the organizational structure of a center, and relationships between referring physicians with imaging centers) were not evaluated in the current study. These unassessed attributes could also have a significant impact on a referring physician’s preference for a specific imaging center.

Conclusion

Of the nine center attributes identified, the availability of a protocol allowing for rapid conversion from an exercise to a pharmacological stress test and assistance in obtaining preauthorization from health insurance had the most significant impact on physician referrals for SPECT-MPI tests. Additionally, cardiologists preferred imaging centers that provide an easy referral process, while PCPs favored centers offering a conclusive statement and actionable steps in test reports. These results may provide useful information to imaging centers wishing to accommodate physician preferences.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Funding for this research was provided by Astellas Pharma Global Development Inc.

Author contributions: All authors participated in the design of the study and contributed to the manuscript development. Data was collected by Analysis Group Inc. and analyzed and interpreted in collaboration with all other authors. The authors collectively vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data reported and the adherence of the study to the protocol. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work, and made the decision to submit the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

C.R.H., J.R.S., R.M.K. and T.M.K. have disclosed that they are employees of Astellas Pharma Global Development Inc. J.L., H.Y., C.Q.X., and E.Q.W. have disclosed that they are employees of Analysis Group Inc., which has received consultancy fees from Astellas Pharma Global Development Inc.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work, but have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing assistance was provided by Shelley Batts, PhD an employee of Analysis Group Inc., ultimately paid by the sponsor, Astellas Pharma Global Development Inc.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Coronary Artery Disease (CAD). 2015. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/coronary_ad.htm Last accessed 23 March 2017]

- Wong ND. Epidemiological studies of CHD and the evolution of preventive cardiology. Nat Rev Cardiol 2014;11:276-89

- American Heart Association. Heart-Health Screenings. 2016. Available at: http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/Heart-Health-Screenings_UCM_428687_Article.jsp#.V9LFwvkrLmF [Last accessed 30 August 2016]

- Mann DL, Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow RO. Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Health Sciences, 2014

- Wolk MJ, Bailey SR, Doherty JU, et al. ACCF/AHA/ASE/ASNC/HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR/STS 2013 multimodality appropriate use criteria for the detection and risk assessment of stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:380-406

- Parker MW, Iskandar A, Limone B, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of cardiac positron emission tomography versus single photon emission computed tomography for coronary artery disease a bivariate meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2012;5:700-7

- Li J, Li T, Shi R, Zhang L. Comparative Analysis between SPECT Myocardial Perfusion Imaging and CT Coronary Angiography for Diagnosis of Coronary Artery Disease. International Journal of Molecular Imaging 2012;2012:7. doi:10.1155/2012/253475

- Levin DC, Intenzo CM, Rao VM, et al. Comparison of recent utilization trends in radionuclide myocardial perfusion imaging among radiologists and cardiologists. J Am Coll Radiol 2005;2:821-4

- Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:759-69

- Hoe J. Quality service in radiology. Biomed Imaging Interv J 2007;3:e24

- Boland GW. Hospital-owned and operated outpatient imaging centers: strategies for success. J Am Coll Radiol 2008;5:900-6

- Bridges JF, Hauber AB, Marshall D, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health – a checklist: a report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health 2011;14:403-13

- Orme BK. Getting started with conjoint analysis: strategies for product design and pricing research. Madison, WI: Research Publishers LLC, 2010

- de Bekker-Grob EW, Donkers B, Jonker MF, Stolk EA. Sample size requirements for discrete-choice experiments in healthcare: a practical guide. Patient 2015;8:373-84

- Lancsar E, Louviere J. Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making: a user’s guide. Pharmacoeconomics 2008;26:661-77

- Marshall D, Bridges JF, Hauber B, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health – how are studies being designed and reported? An update on current practice in the published literature between 2005 and 2008. Patient 2010;3:249-56

- Ryan M, Farrar S. Using conjoint analysis to elicit preferences for health care. BMJ 2000;320:1530-3

- Ryan M, Gerard K. Using discrete choice experiments to value health care programmes: current practice and future research reflections. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2003;2:55-64

- Ryan M. Discrete choice experiments in health care. BMJ 2004;328:360-1

- Lopiano M, Stolz J, Sunshine J, et al. Physician referrals to radiologists. Am J Roentgenol 1990;155:1327-30

- Seltzer S, Gillis A, Chiango B, et al. Marketing CT and MR imaging services in a large urban teaching hospital. Radiology 1992;183:529-34

- Mozumdar BC, Hornsby DN, Gogate AS, et al. Radiology scheduling: preferences of users of radiologic services and impact on referral base and extension. Acad Radiol 2003;10:908-13

- Sogbein OO, Pelletier-Galarneau M, Schindler TH, et al. New SPECT and PET radiopharmaceuticals for imaging cardiovascular disease. Biomed Res Int 2014;2014:942960

- Santilli J, Vogenberg FR. Key strategic trends that impact healthcare decision-making and stakeholder roles in the new marketplace. Am Health Drug Benefits 2015;8:15-20