Abstract

Objective: To assess the impact of Medicaid prescription copayment policies on anti-psychotic and other medication use among patients with schizophrenia.

Method: The study sample included fee-for-service adult Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Medicaid claims records from 2003–2005 from 42 states and D.C. were linked with county-level data from the Area Resource File and findings from a state Medicaid policy survey. Patient-level fixed-effects regression models examined the impact of increases in generic copayments and generic/brand copayment differentials on monthly use of anti-psychotic (overall and by generic/brand status) and other non-antipsychotic medications. Medications for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes in sub-groups of patients with these comorbidities were also examined.

Results: Prescription copayment changes had a statistically significant but small impact on anti-psychotic use. For instance, for every $1 increase in the minimum or generic copayment per prescription, there was a reduction of 1.4 anti-psychotic drug fills per 100 patient months (relative reduction = 1.9%). The generic/brand copayment differential increases also had a minimal impact in changing utilization of first-generation (generic) and second-generation (brand) anti-psychotics. Effects of copayment changes on non-anti-psychotic medication use were substantially higher; for each $1 generic copayment increase, there was a reduction of 23 non-anti-psychotic drug fills per 100 patient months (relative reduction = 10.1%). Similarly, for each $1 increase in the generic/brand copayment differential, there was a reduction of 15 non-anti-psychotic drug fills (relative reduction = 5.6%). Reductions in the number of prescriptions filled for antidiabetics, antihypertensives, and lipid-lowering agents were 4–11-fold higher than corresponding reductions for anti-psychotics.

Limitations: Because federal law requires pharmacists to fill medications for Medicaid patients regardless of the ability to pay, these results may under-estimate the true impact of copayment increases.

Conclusions: Medicaid prescription copayment increases resulted in only a minimal decline in anti-psychotic medication use, but much larger reductions in use of other medications, particularly cardiometabolic medications.

Introduction

Faced with serious budgetary constraints and rapid growth in prescription drug expenditures, many state Medicaid programs have adopted prescription cost-containment strategies previously used only in the private insurance sector. These strategies have included increasing patient cost sharing and generic/brand copayment differentials (i.e. tiered copayments). The theoretical rationale behind these policies is that higher out-of-pocket payments will reduce utilization of drugs considered to be of low value, and that tiered copayments will encourage use of less expensive generic drugs, leading to decreased prescription expenditures. Because the individuals covered under Medicaid are low income, federal law has limited the extent of cost sharing that states can requireCitation1. However, even small copayment amounts may be sufficient to impede use of needed medications among low-income patients. In particular, higher copayments may place cumulative burden on individuals receiving medications for multiple conditions.

Medicaid prescription copayment changes have particular significance for individuals with schizophrenia, many of whom require pharmacological treatment for both psychiatric and general medical conditions. Anti-psychotic medications are the mainstay therapy for the management of schizophreniaCitation2, and medication adherence is critical to improve disease symptoms, reduce the risk of acute psychotic episodes, and decrease the frequency of psychiatric hospitalizationsCitation3–7. Even relatively small changes in adherence have been associated with changes in the risk of adverse clinical outcomesCitation8. Several studies have investigated the impact of copayments on use of anti-psychotics, and they have generally found that higher copayments are associated with decreased anti-psychotic use (especially in the non-Medicaid setting)Citation9–13. For example, a 25% reduction in psychiatric medication refills was observed among veterans with schizophrenia after their prescription copayments increased from $2 to $7Citation9. To date, only two studies using Medicaid data have examined the impact of copayments of up to $3 on anti-psychotic use and treatment continuity in schizophreniaCitation10,Citation13. However, both of these studies faced methodological limitations; one used a cross-sectional designCitation13, and the other lacked a contemporaneous control groupCitation10, thus potentially questioning the validity of the findings of non-linear reductions in anti-psychotic medication continuity across increasing copayment categories in the formerCitation13 and the significant reduction in anti-psychotic medication use following an increase in copayments in the latterCitation10. Furthermore, none of these studies have examined how increases in tiered copayment differentials impact utilization of generic vs brand anti-psychotic medications among Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Because Medicaid is the largest insurer of individuals with schizophrenia in the USCitation14, a closer examination of the effects of medication copayments on anti-psychotic medication use in adults with schizophrenia in the Medicaid program is warranted.

In addition to the importance of studying the impact in this population on anti-psychotic medications, it is also imperative to examine the effect of copayment increases on other non-anti-psychotic medications for multiple reasons. A complex series of factors (including anti-psychotic medication side-effects and higher rates of risk behaviors such as smoking) contribute to higher rates of metabolic conditions and cardiovascular disease among individuals with schizophrenia, who have up to double the risk of dying from cardiovascular disease compared to the general populationCitation15–18. Evidence indicates that individuals with schizophrenia often receive sub-standard care for hypertension, dyslipidemias, diabetes, and related medical conditions, and thus any additional barriers to appropriate management of these conditions would be cause for concernCitation15,Citation19–21. In light of evidence that individuals may be more likely to skip medications for asymptomatic as opposed to symptomatic conditionsCitation22, cumulative out-of-pocket copayment costs may place individuals at particular risk of skipping medication refills for general medical conditions that are frequently life-shortening. Little is known about whether overall copayment burden could lead Medicaid patients with schizophrenia and co-occurring general medical conditions to skip some medications in favor of others.

In this study, we sought to examine these issues in adults with schizophrenia who were facing stable vs increased prescription copayments, taking advantage of natural longitudinal variation in individual state Medicaid copayment policies. We first examine the impact of increases in Medicaid prescription copayments on use of anti-psychotic medications. By examining data from a time period when first-generation anti-psychotic medications (FGAs) were available as generic medications and second-generation anti-psychotic medications (SGAs) were available only as branded drugs (2003–2005), we were also able to examine the impact of increases in tiered (generic vs brand) copayment differentials on FGA vs SGA use. Next, we evaluate the relative impact of these copayment changes on use of anti-psychotics and other medications in adult patients with schizophrenia. Finally, we assess the relative impact of these copayment changes on use of anti-psychotics and medications for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes in sub-groups of patients with schizophrenia with these conditions.

Method

Study design and data sources

This claims-based study utilized a quasi-experimental design, capitalizing on the natural variation in prescription copayment policies that existed across state Medicaid programs from 2003–2005. During this time period, some state Medicaid programs implemented copayment changes, whereas others did not. Individuals in states that changed their copayment policies during the study period served as the study group, whereas individuals in states that did not change their copayment policies served as a contemporaneous control groupCitation23. Data from 44 states plus the District of Columbia (DC) were used in the analyses. The study was reviewed and approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

The study combined data from three sources: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) data files, the Area Resource File (ARF), and a survey of state Medicaid pharmacy directors conducted by the authors. The 2003–2005 MAX files were used to obtain patient-level information on Medicaid eligibility, medical diagnoses, and prescription drug use. The MAX prescription claims data include elements such as National Drug Code (NDC) numbers, prescription fill dates, quantities of medications dispensed, and number of days supplied. The ARF, which is a county-specific information system on health resources and socioeconomic and environmental characteristics, provides area-level characteristics including statistics on income, education, and availability of psychiatrists in each Medicaid patient’s county of residence. The survey of Medicaid pharmacy directors collected information on each state Medicaid program’s specific policies related to prescription copayments, prescription drug limits, preferred drug lists, prior authorization, and “fail first” (i.e. step therapy) policies, in general and for anti-psychotics specifically. The survey asked each state’s Medicaid program personnel to verify state-specific policy data collected by the authors from published sources and websites against their archived documents, and also to provide data where information was missing. In addition, the dates of implementation for changes in prescription copayments and other policies, if any, were obtained for each state. Medicaid officials were also asked to identify prescription policies that applied to anti-psychotics for each year captured in our data set. The individual-level state-identified data from the MAX files were then merged with state-level policy information from 2003–2005.

Study sample

For analyses of anti-psychotic use, the primary sample included all fee-for-service Medicaid enrollees with full pharmacy benefits and a diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9-CM 295.xx), identified via ≥1 inpatient or ≥2 outpatient claims with that diagnosis during a continuous 12-month identification window during 2003–2005Citation24. Patients were excluded if they were: (1) eligible for both Medicaid and Medicare (i.e. dual eligible), as Medicare is the primary payer for this population and, thus, MAX data are incompleteCitation25; (2) in risk-based Medicaid managed care organizations, since pharmacy benefits are often managed by the private managed care organization rather than the state Medicaid program; (3) less than 21 years of age at the beginning of the identification window; or (4) pregnant at any point from 2003–2005, since federal law exempts these patients from Medicaid copayments.

For the analysis of copayment changes on use of anti-psychotics and medications for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes, we selected patients from the primary sample who also had a comorbid diagnosis for hypertension (ICD-9-CM 401–405), hyperlipidemia (ICD-9-CM 272.0–272.4), or diabetes (ICD-9-CM 250, 357.2, 362.01, 362.02, or 366.41), identified via ≥1 inpatient or ≥2 outpatient claims with those diagnoses during a continuous 12-month identification window across 2003–2005.

A primary analytic file with longitudinal, monthly observations was constructed for each patient to capture measures of monthly use of anti-psychotics and other medications and to detect whether changes in medication use occurred before or after a copayment change in the patient’s state of residence. Observations began with the first month of the 12-month identification window, through December 2005. After the 12-month identification window, individual months were excluded if the patients in that month had a change in status that corresponded to any exclusion criterion (i.e. managed care enrollment, dual status, or no pharmacy benefits). This produced 6,115,454 person-month observations from 202,709 unique patients over the study period. For analysis of anti-hypertensive, lipid-lowering, and anti-diabetic medications (among patients who had ≥1 inpatient or ≥2 outpatient claims for the related condition during the 12-month identification window), the analytic files were sub-sets of the primary analytic file, with monthly observations beginning from the month of the first claim with a comorbid diagnosis of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or diabetes in the 12-month identification window until December 2005.

Anti-psychotic and other medication use measures

Use of anti-psychotics, overall and by FGA/SGA status, was captured through medication adherence and number of 30-day supply-equivalent prescription fillsCitation26. First, monthly measures of adherence to anti-psychotics for each patient were calculated using a measure of the proportion of days covered (PDC)Citation26. The PDC is calculated as the number of days with any anti-psychotic drug supply available in the month divided by the number of days in the monthCitation27. The monthly PDC was also captured separately for FGA and SGA medications.

Second, the number of anti-psychotic prescription fills per month was calculated for each patient over the study period. The number of prescription fills was converted into 30-day supply equivalents to permit standardized comparisons before and after policy changes, as well as between the study group and comparison group. As with PDC, the number of fills for anti-psychotic medications was also calculated separately for FGA and SGA medications. The number of prescription fills per month for other prescriptions (non-anti-psychotic medications [i.e. all other medications], non-anti-psychotic mental health medications, and non-mental health medications) was calculated in a similar manner for each patient in each month of the study period. Similar measures were calculated for cardiometabolic medications including lipid-lowering drugs, anti-hypertensives, or anti-diabetic agents, respectively, among the sub-groups of patients with these comorbidities.

Prescription copayment measures

Our primary independent variables of interest included state-level prescription copayment requirements in each month. These were captured using two variables in the model specifications. The first key independent variable was the minimum copayment required to obtain a prescription in each state in each month. For states with tiered copayments in a given month, the lowest or generic copayment was assigned as the minimum copayment level. For anti-psychotics, this represented the minimum copayment required to obtain any anti-psychotic prescription (i.e. FGA or SGA).

Our second key independent variable captured the difference between the maximum and minimum copayment (or the copayments for brands and generics) in each state in each month. States that had no copayments or flat copayments in a given month had a $0 differential assigned in that month. For anti-psychotics, this variable represented the copayment differential faced by the patient for SGA medications (available only as brand medications during the study period) vs FGA medications (available as generics) in each month.

Analyses

Patient-level fixed-effects models with robust estimation were used to examine how copayment changes affected monthly anti-psychotic medication use, other mental health medication use, and all other medication use, using observations from patients in states that did not implement policy change as controlsCitation28. This fixed-effects estimation strategy controls for relevant time-invariant patient-level and state-level variablesCitation29.

The analyses included time-varying patient-level, county-level, and state-level factors as control variables. The prescription drug hierarchical condition category (RxHCC) risk score for each patient was included to control for prescription need and comorbidity burdenCitation30–33. “Adjustments were also made for county-level variables—metropolitan status (urban/rural), mean per capita income, unemployment rate, and education level—that are known to influence medication adherence”Citation34. Measures of the supply of mental healthcare resources at the county level of each beneficiary’s residence included psychiatric hospital beds per 10,000 persons, and the number of psychiatrists per 10,000 persons. Time varying state-level Medicaid policies were also included as control variables. They included limits on the number of prescriptions per month/year, fail first policies, prior authorization programs, and preferred drug lists.

To test the robustness of study findings, we conducted sensitivity analyses using different sample inclusion criteria. We relaxed the diagnostic sampling criteria related to the identification of patients with schizophrenia (i.e. requiring only one or more inpatient or outpatient claim in the 12-month identification window), the requirement for length of continuous eligibility over the study period (i.e. continuously eligible between 2003–2005), and length of the identification window for the schizophrenia diagnosis (i.e. > 1 inpatient or outpatient claim any time between 2003–2005). All statistical analyses were carried out using Stata version 11.1 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

Results

displays the distribution of copayment requirements across the 44 states and DC at 6-month intervals between January 1, 2003 and December 31, 2005. A total of 12 state Medicaid programs had prescription copayment policy changes during the study period, which included 11 changes in generic or minimum copayments and nine changes in brand or maximum copayments. Although a majority of the states had no copayment requirement change during the study period, there was significant variation in magnitude of the changes when they did occur. Five states increased their minimum copayments by $2 or more, while six states implemented a copayment that increased out-of-pocket cost differentials between brand and generic drugs by $2 or more. Three states experienced copayment decreases for generic medications because of changes from a flat copayment model to either tiered or scaled copayment models.

Table 1. State Medicaid Prescription Copayments, 2003 to 2005

Patient characteristics are presented for the entire sample (N = 202,709) and separately for patients in states that did (n = 47,035) and did not (n = 155,674) change Medicaid prescription copayments (). More than half (55%) of the overall sample was <45 years of age, 51% were males, and 43% were White. Patients in states that implemented copayment changes were more likely to be Black and to live in rural areas and counties with lower incomes than those in states that did not implement copayment changes. On the other hand, patients in both the study and comparison groups were quite similar in their comorbidity burden. In general, baseline medication use measures were also similar across both groups.

Table 2. Sample baseline characteristics.

shows the results of fixed-effects regression analyses, whereby within-person changes in medication use were modeled as a function of within-person changes in copayments. In intervention group states, some of those months were subject to changes in copayment amount. In comparison group states, the copayments remained constant over time. The resulting beta coefficients represent the average change in medication use associated with a $1 increase in the medication copayment variable. Results show that prescription copayment changes had a statistically significant but small effect on anti-psychotic use. For every $1 increase in the generic or minimum copayment, there was a reduction of 0.014 anti-psychotic fills per patient per month. The copayment changes also had a statistically significant but small impact on adherence and prescription refills of both FGA and SGA medications (). In particular, the increases in generic/brand differentials had a minimal impact on reducing SGA (i.e. brand) medication use (–0.007) and almost no impact in terms of magnitude in increasing FGA (i.e. generic) medication use (–0.001). On the other hand, the impact of these copayment changes on non-anti-psychotic medication use was substantially higher. For every $1 increase in the generic or minimum copayments, there was a reduction of 0.23 other medication fills per patient per month. In other words, facing a $1 generic copayment increase, a patient with schizophrenia would reduce one anti-psychotic fill every 71.4 months (1/0.014) and cut one non-antipsychotic fill every 4.3 months (1/0.23). Similarly, for every $1 increase in the generic/brand copayment differential, there was a reduction of 0.15 non-anti-psychotic fills per patient per month, translating into one non-anti-psychotic fill being missed every 6.6 months (1/0.15).

Table 3. Impact of copayment changes on monthly adherence and number of 30-day supply equivalent prescription fills.

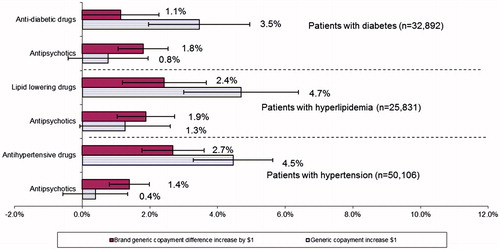

As compared to anti-psychotic fills, the percentage reduction in non-anti-psychotic fills was over 4-times higher for every $1 increase in generic copayments (8.8% vs 1.9%) and over 2-times higher for every $1 increase in the generic/brand copayment differential (5.7% vs 2.6%; ). Further examination within the type of non-anti-psychotic drug fills indicated that the relative impact of every $1 increase in generic copayments was almost twice as large for non-mental health drugs as compared to non-anti-psychotic mental health drugs (10.1% vs 5.4%, ).

Figure 1. Percentage reduction in number of 30-days supply equivalent prescription fills per $1 increase in copayments by anti-psychotic vs non-anti-psychotic drug classes.

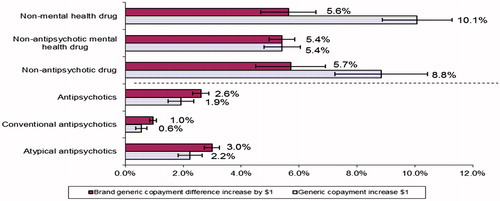

shows the relative comparisons of the percentage reductions in anti-psychotics associated with copayment increases as compared with reductions in medications for diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia in the sub-groups of patients with those conditions. The relative reduction in use due to generic copayment increases was 3.6–11.3-times for all three cardiovascular and metabolic drug classes as compared to anti-psychotics. The relative reduction in use due to generic/brand copayment differential increases was also higher for lipid-lowering drugs and anti-hypertensives as compared to anti-psychotics. Sensitivity analyses using alternative sample inclusion criteria showed similar findings (data not shown).

Discussion

This study is the first to evaluate the longitudinal impact of Medicaid prescription copayment changes on medication use for mental health and cardiometabolic conditions among patients with schizophrenia, using Medicaid data from 42 states and DC. We found that small prescription copayment increases and generic/brand copayment differentials resulted in only a minimal decline in anti-psychotic medication use and adherence (as measured by PDC), but more substantial reductions in use of other medications.

For each $1 increase in the minimum copayment amount, we observed a reduction of 1.4 anti-psychotic drug fills per 100 patient months, corresponding to a relative reduction of ∼1.9% in the mean number of fills per month. From a clinical perspective, it is reassuring that these small increases in prescription copayments had only a limited impact on anti-psychotic medication use, since these drugs are central to the management of schizophrenia, and anti-psychotic non-adherence is a leading source of preventable morbidity in the community management of schizophreniaCitation35. At the same time, there is an established relationship between anti-psychotic adherence and risk of hospitalization in this population, so each missed prescription fill has the potential to influence clinical outcomes.

From a Medicaid program perspective, generic/brand copayment differentials, which might be expected to lead to decreases in use of second-generation anti-psychotics (that were available only as brand medications during our study period), in fact had minimal impact on reducing SGA use and increasing FGA use. This is particularly interesting in light of evidence from large pragmatic clinical trials, suggesting there are few clinical differences between FGAs and SGAsCitation36–39. Our findings provide important data for policy-makers who may be considering broader implementation of differential (or tiered) copayment policies.

Interestingly, increases in prescription copayments and generic/brand copayment differentials had a larger negative effect on non-anti-psychotic medication use. For each $1 increase in minimum copayment, there was a reduction of 23 non-anti-psychotic drug fills per 100 patient months, or a relative reduction of ∼10.1%. Similarly, for each $1 increase in generic/brand copayment differential, there was a reduction of 15 non-anti-psychotic drug fills, or a relative reduction of ∼5.6%. The fact that individuals with schizophrenia appear to be less responsive to increases in copayments for their anti-psychotic medications compared with other medications suggests that the price elasticity of demand for anti-psychotic medications was substantially lower than for non-anti-psychotics. These findings also moderate the long-held perception that the demand for mental health services is particularly sensitive to priceCitation40. These findings also corroborate other research suggesting that patients with certain chronic diseases are not indiscriminate with regard to the choice between disease-specific medications and other medicationsCitation41. Patients were also more likely to forego their non-mental health drugs (e.g. statins) than other mental health drugs (e.g. anti-anxiety agents, anti-depressants). For example, among patients with depression, price elasticity estimates for anti-depressants were reported to be –0.08, whereas it was reported to be –0.25 for non-anti-depressant drugsCitation41. It is possible that individuals prioritized medications that were treating troubling symptoms, as opposed to more asymptomatic cardiovascular conditions. It is unknown whether these reductions had a clinically meaningful impact on the medical outcomes, quality-of-life, and healthcare costs of Medicaid beneficiaries diagnosed with schizophrenia. Nevertheless, it is of concern that individuals were foregoing prescription fills for medications that are used to treat major cardiovascular and metabolic diseasesCitation42,Citation43, which are substantial contributors to premature mortality and reduced life expectancy in individuals with schizophreniaCitation15. Thus, it is important that clinicians and pharmacists counsel such patients and help them make decisions regarding treatment choices in the face of increased cost sharing.

Several study limitations deserve mention. First, Medicaid copayments were not mandatory during our study period. By federal law, pharmacists cannot deny filling prescription drugs for Medicaid patients who cannot make their copayments. However, work by Fahlman et al.Citation44 indicates that 90% of pharmacists always collect copayments. In addition, even if copayments were waived for some patients in states that increased copayments, such waivers would bias our results towards the null; thus, our results may under-estimate the true relationship between copayments and medication use. Second, our study identified patients with schizophrenia in the 3-year study period, but did not include data on duration of illness or prior treatment history. As a result, we are not able to determine whether copayment policies had a differential impact on newly-diagnosed individuals who were initiating anti-psychotic treatment for the first time, as compared to individuals who were further along in their treatment course. We do not expect that duration of illness or treatment history would have differed across our intervention and comparison states, however. Finally, whereas our quasi-experimental study design took advantage of natural variation in state Medicaid copayment policies, our categorization of states into study vs comparison groups may not have been exact if there were other concurrent changes in Medicaid policies (e.g. prior authorization, step therapy requirements, physician visit copays) during the 3-year period. This concern is minimized by the fact that our survey of state Medicaid personnel confirmed that overlap of copayment changes with most other types of policy changes was rare during our study period.

Despite these limitations, our findings have important implications for pharmacological treatment of comorbid conditions in Medicaid patients with schizophrenia and underscore the need for clinicians and pharmacists to be attentive to the risk of interruptions in treatment when patients experience a change in out-of-pocket costs for medication, even if cost sharing increases are small. The findings also have direct implications for the future landscape of Medicaid policies at the state level. Recent legislation has permitted states to increase the maximum nominal copayment limit (otherwise historically fixed at $3 per prescription) in accordance with the percentage increase in the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) each year. While the medical component of the CPI rises at about twice the rate of the overall CPI, the incomes of Medicaid enrollees living below the poverty line tend to rise more slowly than the CPICitation45. Few states now require cost-sharing of up to $4 for preferred drugs and $8 for non-preferred drugs for all Medicaid-covered individuals, including individuals with incomes at or below 150% of the federal poverty levelCitation1. This may place many impoverished, Medicaid patients with schizophrenia at risk of facing higher out-of-pocket costs that would consume a larger share of their limited incomes over time. Given the ongoing attempts to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act, the situation is likely to get worse with the enormous increases in state budgetary pressures if the proposals to revamp Medicaid financing in recently proposed Republican healthcare plans come to fruitionCitation46. Thus, ongoing research will be needed to monitor whether Medicaid prescription copayment changes reduce essential medication use and health outcomes in this vulnerable population.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was supported by grant R01-MH080976 from the National Institute of Mental Health and 1-R01-HS018389-01 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

JAD reported serving as a consultant for Allergan, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, Shire, and Vertex; and had received research funding from Abbvie, Biogen, Humana, Janssen, PhRMA, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, and the National Pharmaceutical Council. Her spouse holds stock in Merck and Pfizer. SCM reported serving as a consultant for Allergan, Janssen, and Eli Lilly. PL and SD have no relevant financial relationships to disclose. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work, but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

No assistance in the preparation of this article is to be declared.

References

- Bruen B, Young K. Paying for prescribed drugs in Medicaid: current policy and upcoming changes. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2014. Available at: http://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/paying-for-prescribed-drugs-in-medicaid-current-policy-and-upcoming-changes/. [Last accessed 5 July 2017]

- Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:1-56

- Thieda P, Beard S, Richter A, et al. An economic review of compliance with medication therapy in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psych Serv 2003;54:508

- Weiden PJ, Zygmunt A. The road back: working with the severly mentally ill. Medication noncompliance in schizophrenia: I. assessment. J Pract Psychiatry Behav Health 1997:106-10

- Kane JM. Commentary on the schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) studies. Schizophr Bull 1998;24:20-3

- Kane JM, Marder SR. Psychopharmacologic treatment of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1993;19:287-302

- Davis JM, Gierl B. Pharmacological treatment in the care of schizophrenic patients. In: Bellack AS, editor. Treatment and care for schizophrenia. Orlando: Grune & Stratton; 1984

- Weiden PJ, Kozma C, Grogg A, et al. Partial compliance and risk of rehospitalization among California Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Psych Serv 2004;55:886

- Zeber JE, Grazier KL, Valenstein M, et al. Effect of a medication copayment increase in veterans with schizophrenia. Am J Manag Care 2007;13:335-46

- Hartung DM, Carlson MJ, Kraemer DF, et al. Impact of a Medicaid copayment policy on prescription drug and health services utilization in a fee-for service Medicaid population. Med Care 2008;46:565-72

- Gibson TB, Jing Y, Kim E, et al. Cost-sharing effects on adherence and persistence for second-generation antipsychotics in commercially insured patients. Manag Care 2010;19:40-7

- Kim E, Gupta S, Bolge S, et al. Adherence and outcomes associated with copayment burden in schizophrenia: a cross-sectional survey. J Med Econ 2010;13:185-92

- Brown JD, Barrett A, Caffery E, et al. Medication continuity among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Psych Serv 2013;64:878-85

- Khaykin E, Eaton WW, Ford DE, et al. Health insurance coverage among persons with schizophrenia in the United States. Psych Serv 2010;61:830-4

- Ringen PA, Engh JA, Birkenaes AB, et al. Increased mortality in schizophrenia due to cardiovascular disease - a non-systematic review of epidemiology, possible causes, and interventions. Front Psychiatry 2014;5:137

- Hennekens CH, Hennekens AR, Hollar D, et al. Schizophrenia and increased risks of cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J 2005;150:1115-21

- Carney CP, Jones L, Woolson RF. Medical comorbidity in women and men with schizophrenia: a population-based controlled study. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:1133-7

- Crump C, Winkleby MA, Sundquist K, et al. Comorbidities and mortality in persons with schizophrenia: a Swedish national cohort study. Am J Psychiatry 2013;170:324-33

- Correll CU, Nielsen J. Antipsychotic-associated all-cause and cardiac mortality: what should we worry about and how should the risk be assessed? Acta Psychiatr Scand 2010;122:341-4

- Mitchell AJ, Lord O. Do deficits in cardiac care influence high mortality rates in schizophrenia? A systematic review and pooled analysis. J Psychopharmacol 2010;24:69-80

- Druss BG, Bradford WD, Rosenheck RA, et al. Quality of medical care and excess mortality in older patients with mental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58:565-72

- Li P, McElligott S, Bergquist H, et al. Effect of the Medicare Part D coverage gap on medication use among patients with hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:776, 84, W-263, W-264, W-265, W-266, W-267, W-268, W-269

- Mortensen K. Copayments did not reduce Medicaid enrollees’ nonemergency use of emergency departments. Health Aff 2010;29:1643

- Lurie N, Popkin M, Dysken M, et al. Accuracy of diagnoses of schizophrenia in Medicaid claims. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1992;43:69-71

- Hennessy S, Leonard CE, Palumbo CM, et al. Quality of Medicaid and Medicare data obtained through Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Med Care 2007;45:1216

- Menzin J, Boulanger L, Friedman M, et al. Treatment adherence associated with conventional and atypical antipsychotics in a large state Medicaid program. Psych Serv 2003;54:719-23

- Peterson AM, Nau DP, Cramer JA, et al. A checklist for medication compliance and persistence studies using retrospective databases. Value Health 2007;10:3-12

- Wooldridge JM. Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press; 2002

- Allison PD. Fixed effects regression methods for longitudinal data using SAS. NC: SAS Publishing; 2005

- Robst J, Levy JM, Ingber MJ. Diagnosis-based risk adjustment for Medicare prescription drug plan payments. Health Care Financ Rev 2007;28:15-30

- Wrobel M, Doshi J, Stuart B, et al. Predictability of drug expenditures for Medicare beneficiaries. Health Care Financ Rev 2003;25:37-46

- Stuart B, Doshi J, Briesacher B, et al. Impact of prescription coverage on hospital and physician costs: a case study of Medicare beneficiaries with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Ther 2004;26:1688-99

- Stuart B, Briesacher B, Doshi J, et al. Will Part D produce savings in Part A and Part B? the impact of prescription drug coverage on Medicare program expenditures. Inquiry 2007;44:146-56

- Chernew M, Gibson TB, Yu-Isenberg K, et al. Effects of increased patient cost sharing on socioeconomic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:1131-6

- Valenstein M, Copeland LA, Blow FC, et al. Pharmacy data identify poorly adherent patients with schizophrenia at increased risk for admission. Med Care 2002;40:630-9

- Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al. Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) investigators. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1209-23

- McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, et al. Effectiveness of clozapine versus olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia who did not respond to prior atypical antipsychotic treatment. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:600

- Lewis SW, Barnes TRE, Davies L, et al. Randomized controlled trial of effect of prescription of clozapine versus other second-generation antipsychotic drugs in resistant schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2006;32:715-23

- Jones PB, Barnes TRE, Davies L, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effect on quality of life of second- vs first-generation antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: Cost utility of the latest antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia study (CUtLASS 1). Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63:1079-87

- Frank RG, Goldman HH, McGuire TG. A model mental health benefit in private health insurance. Health Aff (Millwood) 1992;11:98-117

- Goldman DP, Joyce GF, Escarce JJ, et al. Pharmacy benefits and the use of drugs by the chronically ill. JAMA 2004;291:2344-50

- Beary M, Hodgson R, Wildgust HJ. A critical review of major mortality risk factors for all-cause mortality in first-episode schizophrenia: clinical and research implications. J Psychopharmacol 2012;26:52-61

- Laursen TM, Nordentoft M. Heart disease treatment and mortality in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder - changes in the Danish population between 1994 and 2006. J Psychiatr Res 2011;45:29-35

- Fahlman C, Stuart B, Zacker C. Community pharmacist knowledge and behavior in collecting drug copayments from Medicaid recipients. Am J of Health-Syst Pharm 2001;58:389

- The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Deficit reduction act of 2005: implications for Medicaid. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2006. Available at: https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/7465.pdf. [Last accessed 5 July 2017]

- Park E. Medicaid per capita cap would shift costs and risks to states and harm millions of beneficiaries. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; 2017. Available at: http://www.cbpp.org/research/health/medicaid-per-capita-cap-would-shift-costs-and-risks-to-states-and-harm-millions-of). [Last accessed 6 July 2017]