Abstract

Aims: The utilization of healthcare services and costs among patients with cancer is often estimated by the phase of care: initial, interim, or terminal. Although their durations are often set arbitrarily, we sought to establish data-driven phases of care using joinpoint regression in an advanced melanoma population as a case example.

Methods: A retrospective claims database study was conducted to assess the costs of advanced melanoma from distant metastasis diagnosis to death during January 2010–September 2014. Joinpoint regression analysis was applied to identify the best-fitting points, where statistically significant changes in the trend of average monthly costs occurred. To identify the initial phase, average monthly costs were modeled from metastasis diagnosis to death; and were modeled backward from death to metastasis diagnosis for the terminal phase. Points of monthly cost trend inflection denoted ending and starting points. The months between represented the interim phase.

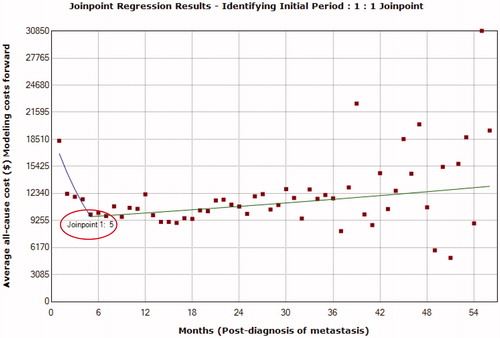

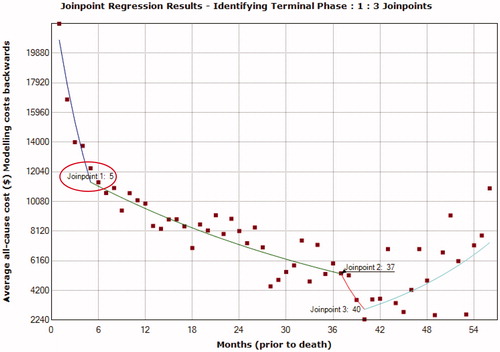

Results: A total of 1,671 patients with advanced melanoma who died met the eligibility criteria. Initial phase was identified as the 5-month period starting with diagnosis of metastasis, after which there was a sharp, significant decline in monthly cost trend (monthly percent change [MPC] = –13.0%; 95% CI = –16.9% to –8.8%). Terminal phase was defined as the 5-month period before death (MPC = –14.0%; 95% CI = –17.6% to –10.2%).

Limitations: The claims-based algorithm may under-estimate patients due to misclassifications, and may over-estimate terminal phase costs because hospital and emergency visits were used as a death proxy. Also, recently approved therapies were not included, which may under-estimate advanced melanoma costs.

Conclusions: In this advanced melanoma population, optimal duration of the initial and terminal phases of care was 5 months immediately after diagnosis of metastasis and before death, respectively. Joinpoint regression can be used to provide data-supported phase of cancer care durations, but should be combined with clinical judgement.

Introduction

Practice patterns in oncology are evolving that necessitate updated estimates of cost of cancer care in the US. Several approaches have been used to estimate costs of cancer care, including incidence, prevalence, and phase of care approachesCitation1. HornbrookCitation2 defined the following three phases of care conceptually: the initial phase of care included the primary course of therapy and any adjuvant therapy normally provided within the first few months of diagnosis (e.g. surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy); the continuing phase of care was composed of surveillance activities for detecting recurrences and new primary cancers, including the treatment of complications derived from the initial course of therapy; and the terminal phase of care included care received at the end of life, which may have been palliative in nature. Cancer cost studies have based estimates on previous studies of direct medical costs or used clinical input or a trend in average monthly costs (defined as the point at which average monthly charges dropped by more than half) to define the duration of phases of careCitation1–3.

The duration of phases of care vary by the type of cancer and the stage of diagnosisCitation3–6. For example, the terminal phase for patients with breast and pancreatic cancer was defined as 12 months before death, whereas the terminal phase was defined as 3 months for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. There has been no consistent basis to define the duration of phases of care, with prior studies defining the phases arbitrarily or based on clinical judgment.

The objective of the current study was to establish a data-driven approach that, in concert with clinical judgment, can be considered a consistent basis to define the phases of care. The current study establishes this methodological approach using advanced melanoma as an example. It is important to note that the timeframe of data used for this analysis pre-dates the advent of newer therapies for the treatment of advanced melanoma, which have had a significant impact on survival. Therefore, the duration of phases of care and costs of advanced melanoma in this analysis should be considered as benchmark data for assessing the impact of future therapies on the cost of care.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using integrated healthcare claims data from the IMS LifeLink PharMetrics Plus™ Claims Database during the period from January 1, 2009, to September 30, 2014. The database contains administrative medical and pharmacy claims and eligibility records for more than 103 different managed healthcare plans, including Blue Cross Blue Shield data, encompassing more than 150 million lives, of which ∼90 million have both medical and pharmacy benefits. All patients aged 18 years or older with evidence of death during the enrollment period (January 1, 2010, to September 30, 2014) were included. Patients without continuous eligibility from date of metastases to date of death were excluded. Additionally, those with a diagnosis of other non-melanoma primary malignancy occurring on, or during 180 days prior to the diagnosis of metastases were excluded unless (1) the other primary cancer was skin cancer or a hematologic malignancy, or (2) the patient had a claim for melanoma on the diagnosis date, or (3) the site of the reported other cancer was the same as the site of metastasis. The study index was defined as the date of death, which corresponded to the date of the last medical claim with a qualifying code used as a proxy for end of life. As date of death is not available in the data source, death was identified using a previously published algorithmCitation7–9. The algorithm defines death as having any of the codes for hospice, cardiac event including cardiac arrest/failure, hospitalization, emergency room visit, ambulance service, or inpatient stay having discharge status of “expired” in the last month before date of last claims activity or disenrollment in the claims database. The algorithm has recently been validated using the 5% Medicare claims data which has both costs data and an indicator for dead/alive. The algorithm performed really well, with a positive predictive value (PPV) for overall death being 99.5%Citation10 (Reference to be added after AMCP 2017).

Patients with advanced melanoma were required to have a diagnosis of metastases (ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes 196.xx, 197.xx, 198.xx) on ≥1 non-diagnostic medical claim (the date of diagnosis of metastases corresponded to the earliest claim for metastases during the study period). For patients with stage III disease, a diagnosis of melanoma (ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes 172.xx) on ≥1 inpatient or ≥2 non-diagnostic outpatient medical claims (on different days) occurring in the 180 days before the date of metastases was required. Patients were defined as having stage IV disease if they met the above criteria and additionally presented with a claim for a skin biopsy or removal of skin lesion procedure in the 180 days before their metastases date with a diagnosis of melanoma on any inpatient or outpatient medical claim within 30 days of the date of the procedure. The selection of the 180-day duration prior to the first date of metastases diagnosis is arbitrary, and was only done to evaluate the claims history closer to the date of metastases to help ensure that the primary cancer related to the metastases was melanoma.

Study outcomes

All-cause costs per month per phase (initial, interim, and terminal) were the main outcomes of interest and were reported by phase of care. Components of the total all-cause costs (medical and prescription) were also computed. Costs were based on the total paid amounts of adjudicated claims to providers of care, including insurer payments and patient cost-sharing in the form of deductibles, co-payments, and coinsurance, and were adjusted to 2014 US dollars by the medical component of the consumer price index. All-cause resource use in terms of the number and percentage of patients by site of care (inpatient or outpatient, including emergency department, office, and other outpatient visits) was reported by phase of care to understand the drivers of costs, as was the use of melanoma-related treatment, defined as radiation therapy, surgery, and drug treatment, including chemotherapy, biologic therapy (immunotherapies), and molecularly targeted therapies.

Analysis

Joinpoint regression analysis was performed using the Joinpoint Trend Analysis Software originally developed by the National Cancer Institute to analyze the trends of cancer-related incidence, prevalence, mortality, and survivalCitation11. The dependent variable in the joinpoint regression was the monthly all-cause healthcare costs (log-transformed) and the independent variable was the time in monthly intervals from diagnosis of metastasis to death. Joinpoint regression is a piecewise linear regression used to identify the best-fitting points, where statistically significant changes in the trend of monthly costs occurCitation12. Two models were estimated: one for the initial phase and the second for the terminal phase. A heteroskedastic, uncorrelated error model was used for both, based on the Cook–Weisberg test for heteroscedasticity and the Breusch–Godfrey LM test for autocorrelation. Average monthly costs were modeled from metastasis diagnosis to death for the initial phase model, and costs were modeled backward from death to metastasis diagnosis for the terminal phase model. A sequential algorithm-based method called grid search was used to identify the best fit of data, where a minimum of one to a maximum of three joinpoints were specified for each model. Joinpoints were defined as points of inflection in the trend of the dependent variable, which in this case were monthly costs. Bonferroni correction was used for the overall significance-level testing of joinpointsCitation12. The joinpoints were then used to estimate the duration of the initial and terminal phases. The months in-between represented the interim phase.

Results

A total of 1,671 patients with advanced melanoma who died met the study criteria (). The average age of patients with advanced melanoma was 61.2 ± 12.6 years, with a higher proportion of the study population between 55 and 64 years of age (). The average comorbidity burden, as measured by the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), was 2.5 ± 2.6. The mean time from diagnosis of metastasis to death in days was 383 ± 349 days, with 75% of the sample having an event of death within a year of diagnosis of metastases.

Table 1. Sample attrition.

Table 2. Sample description.

The duration of the initial phase () was identified as the 5 months from diagnosis of metastasis using a 1-joinpoint model identified as the best fit using the grid search method. Following the diagnosis of metastasis there was a statistically significant and sharp decline in monthly cost trend at month 5 (monthly percent change [MPC] = −13.0%; 95% confidence interval [CI] = −16.9% to –8.8%). The duration of terminal phase () was identified as the 5 months before death using a 3-joinpoint model identified as a best fit with the grid search method. There was a statistically significant and sharp decline in monthly cost trend at month 5 (MPC = −14.0%; 95% CI = −17.6% to −10.2%) before death.

Once the joinpoints were identified, the time from diagnosis of metastases to death for each patient was divided into phases depending on the total duration of time available. For patients with ≤11 months from metastases diagnosis to death, the time period of up to 5 months preceding the date of death was first allocated to the terminal phase, and then the remainder to the initial phase with no interim phase. Patients with ≤5 months by definition were only assigned a terminal phase.

As the study criteria included all patients who died, all patients were included in the terminal phase with 1,167 and 810 patients evaluated in the initial and interim phases, respectively (). All-cause average monthly costs in the terminal phase were the highest ($17,746), with costs doubling from the interim to the terminal phase (). Monthly costs in the initial phase ($11,852) were lower than terminal costs, but higher than interim costs ($8,868). Thus, the distribution of medical costs followed a similar trend as the total costs, but prescription costs increased steadily across the phases (initial = $704; interim = $1,006; terminal = $1,241).

Table 3. All-cause monthly cost and resource use by phase of care in all patients.

The distribution of inpatient resource use for patients with advanced melanoma followed a U-shaped curve similar to that of the monthly costs. Inpatient resource use was higher in the initial phase, followed by lower interim resource use, and the highest inpatient resource use was in the terminal phase (i.e. initial = 44.9%; interim = 41.9%; terminal = 78.0%; ). Outpatient resource use was relatively similar across all phases of care, decreasing slightly from initial to terminal for all types of outpatient resource use, except for use of emergency department visits, which increased across all phases from 18.1% to 41.0% during the initial and terminal phases, respectively.

Approximately 70% of patients with advanced melanoma had evidence of a melanoma-related therapy during the initial and terminal phases of care. Use of radiation therapy almost doubled from the interim to the terminal phase (25% to 45%, respectively) and surgery dropped by half from the initial to the interim phase (42% to 24%, respectively) and continued to decrease in the terminal phase (16%). Drug therapy, including immunotherapy, molecularly targeted therapies, and chemotherapy, was used by one-quarter to one-third of patients in all phases.

Discussion

The use of joinpoint regression in this advanced melanoma population who died helped identify the optimal duration of the initial and terminal phases of care to be 5 months immediately after diagnosis of metastasis and before death, respectively. Furthermore, the pattern of monthly all-cause costs of care following the diagnosis of metastasis to death in patients with advanced melanoma was similar to the trend following the diagnosis of (any) cancer until death, which is U-shapedCitation3, with initial monthly costs being higher, followed by lower interim costs and, finally, higher costs in the terminal phase.

While phase-based costing is increasingly being recognized as the method of choice for costing oncology studies, the method of assessing phases has differed. For example, Chang et al.Citation5 defined three phases of care for pancreatic cancer based on shifts in the treatment of cancer patients as the disease progressed. The initial treatment phase was defined as the period from first cancer diagnosis until the switch to a new intervention 3 months following the last administered cancer-related treatment (chemotherapy, radiation, or surgery). Secondary treatment phase was the period after treatment switch until diagnosis of advanced cancer or onset of palliative care, and the third phase was called the palliative treatment phaseCitation3. A previous cost of melanoma study, involving patients with either advanced or non-advanced melanoma, defined the end of the initial phase as the point at which the average monthly charges per-patient dropped by more than one-half (4 months) and the terminal phase was defined as the 6-month period before melanoma-related deathCitation4. The joinpoint technique has been used by other researchers to define the phases of care for colorectal cancer and hepatocellular carcinomaCitation13,Citation14. This technique affords a more precise estimation through empirical means of defining the phases of care.

In the case of melanoma, the cost per phase in this study of only advanced melanoma was much higher compared with prior studies evaluating all patients with melanoma (i.e. with or without advanced melanoma)Citation15. In a study using phase-based costing method to assess costs of melanoma, the average monthly per-patient melanoma charges in the previous study were $2,194 during the initial phase (4 months), $902 during the interim phase, and increased to $3,933 during the terminal phase (6 months)Citation4. Higher costs in the current study may be attributable to the types of therapy available for the treatment of advanced melanoma at the time of this study; the previous study was conducted between 1991 and 1996.

While researchers have used the joinpoint method in colorectal cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma, this paper demonstrates the application of the joinpoint method for the first time in advanced melanoma. The strengths of the study include assessment of melanoma costs in a relatively younger population compared to other published estimates to-date. Furthermore, we restricted the study population to only those with advanced melanoma who died, and, hence, the estimation of especially terminal phase costs is likely to be more accurate compared to other studies that include patients across stages. There are certain limitations, however, that should be highlighted. First, this study used a claims-based algorithm to identify diagnosis of metastasis and death. The diagnoses of metastases were identified using a claims-based algorithm, which has not yet been validated, and, in the absence of clinical data, this may have led to the under-estimation of patients who have metastases of melanoma if patients were misclassified. Regarding stage IV, the ICD codes for distant metastases does not include distant lymph nodes. The diagnosis code 196.xx—metastases to lymph nodes was used for stage III, and distant vs regional cannot be differentiated. The algorithm used both hospitalizations and emergency department visits in the last month before the last claim date and the end of enrollment as a death proxy, which may over-estimate costs in the terminal phase. Furthermore, the cost estimates for advanced melanoma may be under-estimated and not reflective of the current cost of therapy because newer therapies, approved after the study period, were not included. As a result, caution should be exercised when using initial- and terminal-phase cost estimates from this study, as it is anticipated that newer cancer therapies could prolong survival in a greater number of patients and would, therefore, increase the initial phase-of-care costs to the point where they might be higher than terminal costs for patients with advanced melanoma. Furthermore, the possibility of a cure due to newer therapies may render the terminal phase obsolete with regards to death from advanced melanoma and, therefore, affect the estimates associated with the cost of care for patients in the terminal phase. The results are only generalizable to advanced melanoma and not all melanoma patients, and primarily to patients enrolled in commercial health plans and less to the Medicare and Medicaid population. Future research using the joinpoint methodology may be used in conjunction with other methods to evaluate other objectives, for example, use of a matched control group to evaluate the incremental cost of melanoma or use of survival methods in combination with phase-based costs to estimate lifetime costs. Also, use of this methodology in conjunction with data that allows for assessment of disease progression may be useful to evaluate the association between phases of care and disease progression. While it is possible that the timing of progression may be related to the phase duration, especially from interim to terminal phase, it is unlikely to be related to the change from initial to interim. Nevertheless, differences in progression-free survival between treatments may impact the phase-based costing approach time points.

Conclusions

In this advanced melanoma population, the optimal duration of the initial and terminal phases of care was 5 months immediately after diagnosis of metastasis and before death, respectively. This data-supported approach, using joinpoint regression, should be complemented with clinical judgment to identify the appropriate duration of phases of care for reporting costs from the diagnosis of metastasis to death. This study could set the stage for future cost studies involving patients with advanced melanoma by phases of care, especially in light of newer therapies that prolong life.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

MA is an employee of Georgetown University and has received consultant fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb. ADC and ME are employees of Xcenda, which has received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb for the conduct of this study and for the preparation of this manuscript. SN is a student at the University of Mississippi and was an intern at the time of conduct of this study. KG-S is an employee of Bristol-Myers Squibb. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Previous presentation

Nunna S, Coutinho AD, Eaddy M, Landsman-Blumberg P. Use of joinpoint regression to define phases of care from diagnosis of metastases until death in patients with advanced melanoma. Presented at the 21st ISPOR Annual Meeting 2016; Value in Health Vol 19 (3); Pg A6.

Acknowledgments

Pamela Landsman-Blumberg from Xcenda for strategic oversight and review of the analysis and manuscript, Jasmine Knight from Xcenda for her medical writing services, and StemScientific, an Ashfield Company, for editorial services funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

References

- Yabroff KR, Davis WW, Lamont EB, et al. Patient time costs associated with cancer care. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007;99:14-23

- Hornbrook MC. Definition and measurement of episodes of care in clinical and economic studies. In Conference Proceedings: Cost Analysis Methodology for Clinical Practice Guidelines, edited by Grady MC, Weis KA. DHHS Pub No (PHS) 95-001. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1995, pp 15-40

- Brown ML, Riley GF, Schussler N, et al. Estimating health care costs related to cancer treatment from SEER-Medicare data. Med Care 2002;40(Suppl8):IV-104-17

- Seidler AM, Pennie ML, Veledar E, et al. Economic burden of melanoma in the elderly population: population-based analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)–Medicare data. Arch Dermatol 2010;146:249-56

- Chang S, Long SR, Kutikova L, et al. Burden of pancreatic cancer and disease progression: economic analysis in the US. Oncology 2006;70:71-80

- Paramore LC, Thomas SK, Knopf KB, et al. Estimating costs of care for patients with newly diagnosed metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2006;6:52-8

- Joyce AT, Iacoviello JM, Nag S, et al. End-stage renal disease-associated managed care costs among patients with and without diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004;27:2829-35

- Fintel D, Joyce A, Mackell J, et al. Reduced mortality rates after intensive statin therapy in managed-care patients. Value Health 2007;10:161-9

- Pelletier EM, Shim B, Goodman S, et al. Epidemiology and economic burden of brain metastases among patients with primary breast cancer: results from a US claims data analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008;108:297-305

- Stafkey-Mailey D, Wang W, Murty S, Shetty S. Validation of an Algorithm to Identify Death in Administrative Claims Data. JMCP 2017;23:S38

- National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Cancer Institute. Surveillance research program: Joinpoint trend analysis software. Version 4.2.0 – April 2015; Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch. https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/

- Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, et al. Permutation tests for Joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med 2000;19:335-51 (correction: 2001;20:655)

- Thein HH, Isaranuwatchai W, Campitelli MA, et al. Health care costs associated with hepatocellular carcinoma: a population-based study. Hepatology 2013;58:1375-84

- Brown ML, Riley GF, Potosky AL, et al. Obtaining long-term disease specific costs of care: application to Medicare enrollees diagnosed with colorectal cancer. Med Care 1999;37:1249-59

- Guy GP Jr, Ekwueme DU, Tangka FK, et al. Melanoma treatment costs: a systematic review of the literature, 1990–2011. Am J Prev Med 2012;43:537-45