Abstract

Aims: Due to the lack of studies evaluating compliance or persistence with Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) treatment outside High-Income Countries (HICs), this study aimed to assess compliance, persistence, and factors associated with non-compliance and non-persistence by utilizing existing “real-world” information from multiregional hospital databases in Thailand.

Materials and methods: Study subjects were retrospectively identified from databases of five hospitals located in different regions across Thailand. AD patients aged ≥60 years who were newly-prescribed with donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, or memantine between 2013 and 2017 were eligible for analysis. The Medication Possession Ratio (MPR) was used as a proxy for compliance, while the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was employed to estimate persistence. Logistic and Cox regressions were used to assess determinants of non-compliance and non-persistence, adjusted for age and gender.

Results: Among 698 eligible patients, mean (SD) MPR was 0.83 (0.25), with 70.3% of the patients compliant to the treatment (having MPR ≥ 0.80). Half of the patients discontinued their treatment (having a treatment gap >30 days) within 177 days with a 1-year persistence probability of 21.1%. The patients treated in the university-affiliated hospital were more likely to be both non-compliant (OR = 1.71; 95% CI = 1.21–2.42) and non-persistent (HR = 1.33; 95% CI = 1.12–1.58). In addition, non-compliance was higher for those prescribed with single AD treatment (OR = 2.52; 95% CI = 1.35–4.69), while non-persistence was higher for those unable to reimburse for AD treatment (HR = 1.34; 95% CI = 1.11–1.62).

Limitations: By using retrospective databases, a difficulty in validating whether the medications are actually taken after being refilled may over-estimate the levels of compliance and persistence. Meanwhile, possible random coding errors may under-estimate the strength of association findings.

Conclusions: This study reveals the situation of compliance and persistence on AD treatment for the first time outside HICs. The determinants of non-compliance and non-persistence underline key areas for improvement.

Introduction

By 2050, nearly two thirds of countries across the world will have become aged societyCitation1, where at least 20% of the population is aged 60 years or over. As incidence of dementia doubles with every 6.3-year increase in age after 60 years, up to 131.5 million people worldwide will have lived with dementia by the same yearCitation2. Approximately three quarters of all dementia cases are caused by Alzheimer’s disease (AD)Citation3. AD is a chronic disorder of the brain, causing a progressive deterioration of cognitive functions. People with AD gradually lose abilities to execute daily activities and become dependentCitation4. There are two classes of medications having efficacy of improving cognition, behavior, and global status of people with AD: (1) cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs: donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine); and (2) N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist (NMDA antagonist: memantine)Citation5–7.

Compliance and persistence play a crucial role in allowing patients to achieve the highest benefits from their prescriptions. The Special Interest Group (SIG) of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcome Research (ISPOR) has recommended that compliance and persistence should be defined and considered separatelyCitation8. Compliance assesses how well a patient acts in accordance with the prescribed regimen, while persistence measures how long a patient continues the treatment for the prescribed duration. A review of long-term use of ChEIs has suggested that treatment with ChEIs be continued for at least 1 year before discontinuation so that treatment effects can remain for up to 5 yearsCitation9. Furthermore, a cohort study of 8,614 AD patients has found that the sustained use of ChEIs for more than 2 years decreases annual mortality risk by 24%, compared to the short-term use for less than 1 yearCitation10.

Despite the paramount importance of compliance and persistence on patient’s outcomes, to date, the studies evaluating such behavior specifically with AD treatment have only been conducted in High-Income Countries (HICs)Citation11. The evaluation of compliance and persistence could be performed using either subjective (i.e. patient’s self-report and healthcare professional assessments) or objective (i.e. pill counts, electronic monitoring, secondary database analysis and biochemical measures) methodsCitation12. With the possibility of resource constraints in non-HICs, analyzing compliance and persistence behavior using secondary database analysis, which requires minimal time and expenditure, is considered appropriate, particularly for those non-HICs where pharmacy or claimed databases have been availableCitation13.

Thailand, a member of non-HICs, also has experience with the growing number of elderly, with no less than a half million AD cases in 2015Citation14,Citation15. Nonetheless, access to AD treatment for Thai patients has been limited. AD medications can only be prescribed in tertiary hospitalsCitation16, and are only subsidized by the Civil Servant Medical Benefit Scheme (CSMBS, covering 8% of entire Thai population)Citation17. While this is an important issue to be addressed, without the availability of relevant Health Technology Assessments (HTAs), decision-making on health policies for tackling this issue is susceptible to uncertaintyCitation18. The study of compliance and persistence behavior of AD treatment would provide crucial insights into the current situation of compliance and persistence levels among AD treatment users in Thailand. Knowledge of compliance and persistence can serve not only as a key input parameter for its own future full HTAs, but also as a reference for other non-HICs to develop their own study. We, therefore, aimed to assess compliance, persistence, and factors associated with non-compliance and non-persistence by utilizing existing “real-world” information from multiregional hospital databases in Thailand.

Methods

This study was reported in accordance with the recommendation of the ISPOR Medication Compliance and Persistence SIG to ensure the consistency and quality of compliance and persistence findingsCitation19.

Data sources

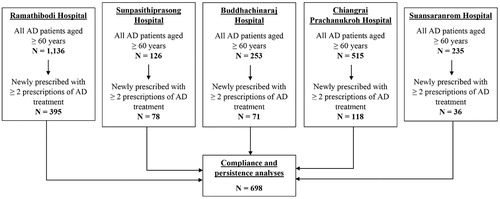

We retrospectively identified the study population from five hospital’s databases located in different regions of Thailand: (1) Ramathibodi Hospital, Bangkok, central Thailand (a 1,378-bed university-affiliated hospital); (2) Sunpasithiprasong Hospital, Ubon Ratchathani, northeastern Thailand (a 1,188-bed regional hospital); (3) Buddhachinaraj Hospital, Phitsanulok, lower northern Thailand (a 1,063-bed regional hospital); (4) Chiangrai Prachanukroh Hospital, Chiangrai, upper northern Thailand (a 787-bed regional hospital); and (5) Suansaranrom Hospital, Surat Thani, southern Thailand (a 1,300-bed psychiatric hospital). We requested de-identified datasets consisting of outpatient and inpatient information on demographics, diagnosis, hospital visits, and prescribed medications from each hospital. The first four hospitals provided datasets from January 1, 2013 to December 31, 2015, with another from October 3, 2014 to August 3, 2017 due to data availability. Ethical approvals on the study protocol were granted from all five hospital’s ethics committee.

Study subjects

Study subjects included elderly people aged 60 or above with a diagnosis of AD according to the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10) codes as F00 (dementia in Alzheimer’s disease) and G30 (Alzheimer’s disease)Citation20, who were newly-prescribed with at least two successive prescriptions of donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, or memantine within the first 6 monthsCitation21. New AD treatment users were identified as not receiving any of the four AD medications during the past 6 months prior to the index prescription date (the date of the first AD treatment prescription for each subject)Citation13,Citation22. Datasets of each eligible study subject were analyzed in a 1-year period following their index date.

Measurements of compliance and persistence

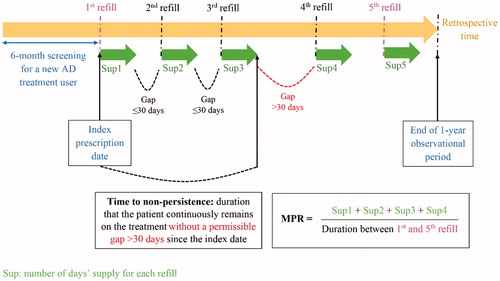

We estimated the Medication Possession Ratio (MPR) as a proxy for compliance to AD medications. MPR was calculated by summing the number of days for which the treatment had been supplied during the observational period without the last refill, divided by the number of days between the first and the last refillCitation19. Patients with MPR ≥0.8 were considered to be compliant AD treatment usersCitation23. In the case that MPR was greater than 1.0, which reflected patients refilling AD treatment before the depletion of their previous supply, we capped the MPR value at 1.

We employed the Estimated Level of Persistence with Therapy (ELPT) approach to measure time to non-persistence and persistence probabilitiesCitation13,Citation19. Time to non-persistence, equivalent to time to treatment discontinuation, was defined as the duration that the patient continuously stayed on AD treatment without a permissible gap (a period of time between the expected exhaustion of one prescription and the initiation of subsequent prescription) exceeding 30 consecutive days, counting from the index dateCitation22,Citation24. Persistence probabilities were identified as proportions of patients persistent with their AD treatment at a given time throughout the observational period of 1 yearCitation13,Citation19.

Since switching from initial AD treatment to another was neither non-adherent nor non-persistent behavior, which benefited the patients as it lengthened the overall treatment duration; therefore, we allowed the switchers to remain in the analysesCitation25. Measurements of compliance and persistence are illustrated using a hypothetical example of AD treatment refilling course in .

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data of patient characteristics, compliance (MPR, percentage of compliant subjects), and persistence (median time to non-persistence, persistence probability). The survival curve of persistency probabilities over the observational period was generated using the Kaplan–Meier estimateCitation26. Bivariate analyses, logistic, and the Cox proportional hazard models were used to determine factors that potentially had influences on compliance and persistenceCitation27. These factors included age, gender, types of hospital, types of AD treatment, use of AD combination treatment, use of patch dosage form, polypharmacy (prescription of ≥ five medications during 6 months preceding the index date), and reimbursement status for AD prescription costsCitation28,Citation29. Sensitivity analyses were carried out to check robustness of the findings as follows: (1) excluding the datasets from a hospital which captured a different period of prescribing information; and (2) varying the permissible gap of persistence analysis to 15, 45, and 60 daysCitation24. Results from the sensitivity analyses were compared to those from the main analyses using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis testCitation30. All data processing and statistical analyses were undertaken in STATA (version 13.0, StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Characteristics of study subjects

A total of 698 eligible AD patients were identified from all five hospital databases. Details of the study subject selection are outlined as a flow diagram in . Of the 698 patients, the mean (SD) age was 78.1 (7.8) years; and 445 (63.8%) were female. Donepezil (339/698, 48.6%) was most frequently prescribed as the first AD treatment, followed by memantine (169/698, 24.2%), rivastigmine (111/698, 15.9%), and galantamine (79/698, 11.3%). About one in 10 patients (88/698, 12.6%) initiated their treatment with AD combination treatment, which was comprised of one type of ChEIs plus memantine. None of the patients starting with multiple AD medications had their AD treatment switched, whereas 11.8% (72/610) of those starting with single AD medication did. The majority of patients (478/698, 68.5%) were found to have polypharmacy in the past 6 months prior to the index date. Almost three quarters of new AD treatment users (517/698, 74.1%) were the patients insured under the CSMBS (8% of all population whose AD treatment costs were subsidized), leaving a small proportion (25.9%) of accessibility to new AD treatment prescriptions to the rest of the Thai population (92%). Characteristics of study subjects are presented in .

Figure 2. Identification of eligible study subjects from five hospitals’ databases in Thailand for compliance and persistence analyses.

Table 1. Distribution of study subject’s characteristics.

Measures of compliance and persistence with AD treatment

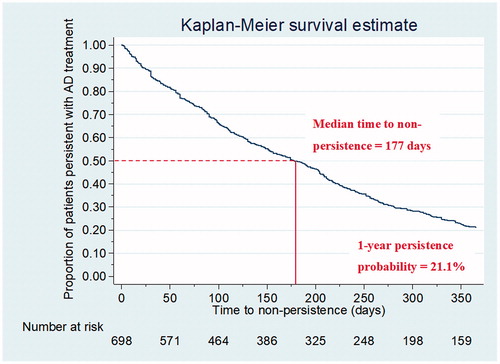

Medication compliance among Thai AD treatment users was fairly high, with a mean MPR (SD) of 0.83 (0.25). When applying the cut-off value of MPR at 0.80, we found that seven out of 10 patients (70.3%; 95% CI = 66.8–73.7%) were compliant to AD treatment. According to the survival curve of persistence probabilities with AD treatment shown in , median time to non-persistence was slightly shorter than 6 months (177 days; IQR = 72–330 days). However, there were only 21.1% (95% CI = 18.1–24.2%) of the patients persistent with their treatment for a 1-year period following the index date.

Determinants of medication non-compliance

Factors potentially associated with non-compliance to AD treatment () were found to be (1) receiving AD treatment from a university-affiliated hospital, (2) using single AD medication, and (3) using a non-patch dosage form (p-value of the Chi-square statistics <.2). These factors were further verified using the multivariate logistic regression. According to the forward selection process, the final model (), adjusted for age and gender, revealed that (1) receiving AD treatment from the university-affiliated hospital (Odds Ratio (OR) = 1.71; 95% CI = 1.21–2.42; p-value = .003), and (2) using single AD medication (OR = 2.52; 95% CI = 1.35–4.69; p-value = .004) were statistically significant determinants of non-compliance to AD treatment.

Table 2. Bivariate analyses exploring associations between patient characteristics and compliance with AD treatment.

Table 3. Multivariate analyses of the patient characteristics selected from the bivariate analyses to investigate determinants of non-compliance and non-persistence.

Determinants of medication non-persistence

Factors potentially related to non-persistence with AD treatment () included (1) receiving AD treatment from university-affiliated hospital, and (2) being ineligible for AD treatment reimbursement (p-value of the Chi-square statistics <.2). We, therefore, further investigated these factors using the multivariate Cox regression. Based on the forward selection process, the final model (), adjusted for age and gender, disclosed that (1) receiving AD treatment from the university-affiliated hospital (Hazard Ratio (HR) = 1.33; 95% CI = 1.12–1.58; p-value = .001), and (2) being ineligible for AD treatment reimbursement (HR = 1.34; 95% CI = 1.11–1.62; p-value = .002) were statistically significant determinants of non-persistence with AD treatment. These determinants did not violate the proportional-hazards assumption of the Cox model.

Table 4. Bivariate analyses exploring associations between patient characteristics and persistence probabilities with AD treatment.

Sensitivity analyses

In the sensitivity analyses (), exclusion of the datasets, in which different periods of prescribing information was captured, did not significantly alter the results from the main analysis (p-values of the Kruskal-Wallis tests on mean MPR and median time to non-persistence >.05). However, variations of permissible gap in persistence analysis lead to significant differences in median time to non-persistence and 1-year persistence probability, compared to the main analysis (p-values of the Kruskal-Wallis tests ≤.05). Not surprisingly, both of the persistence outcomes were increased with more flexible permissible gaps.

Table 5. Sensitivity analyses.

Discussion

Principal findings

This study generates the first “real-world” evidence of compliance and persistence on AD treatment outside HICs. We found that most of the patients (70.3%) were compliant to their treatment, whereas only 21.1% could manage to persist with the treatment throughout the 1-year observational period. Co-prescription of AD medications was found to exert a positive influence on the level of compliance. However, the patients who received AD treatment from the university-affiliated hospital were deemed to have significantly higher chances of being both non-compliant and non-persistent. Only a small portion of the Thai population, particularly those whose AD treatment expenses were subsidized, had access to AD treatment and remained on the treatment for a longer duration. These findings reveal the current status of compliance and persistence behavior and highlight specific areas to consider for improving levels of such behavior among AD treatment users in Thailand.

Levels of compliance and persistence with AD treatment

Compliance and persistence provide different perspectives of medication-taking behavior. As recommended by the SIG of ISPORCitation8, we defined and assessed both of them independently. Overall, Thai AD patients appeared to have high-compliant (70.3% were found to be compliant to AD treatment over 1 year) but low-persistent (21.1% were found to be persistent with AD treatment over 1 year) behavior. They may possess enough medications to consume with respect to the prescribed regimen, but they intermittently take the medications with an early treatment gap that goes beyond the tolerable level. Since it has been reported that interruption of donepezil for more than 6 weeks can lead the patients to lose all benefits gained from the previous treatmentCitation31, we decided to use the 30-day permissible gap, which is more sensitive to detect discontinuation, in our main analysis. The large difference between compliant and persistent levels could be explained by the differences in methodology between the MPR and the ELPT. The major difference is that the calculation of MPR does not consider the gaps between refills, thus tolerating the gaps of every levelCitation13, resulting in the higher estimates. Hence, the recommendation of the SIG should be encouraged because considering only one measure instead of another could lead to partial understanding or even misapprehensions of medication-taking behavior.

When compared to existing literature, although our compliance and persistence levels are somewhat similar to those of other countries, the levels are fallen on the lower half percentile of worldwide results. The majority of studies have used the MPR to quantify compliance on AD treatment, although the variations of MPR formulas are found across the studiesCitation10,Citation23,Citation32–36. The reported MPRs have ranged from 0.59Citation35 to 0.94Citation33, placing our MPR of 0.83 on about the 45th percentile of all available results from the seven studies. Turning to consider the studies assessing persistence on AD treatmentCitation10,Citation22–24,Citation29,Citation32,Citation35–43, a wide range of permissible gaps have been used from 30Citation22,Citation24,Citation32,Citation35,Citation37,Citation38 to 180 daysCitation43. Most of the studies have defined the gap of 30 days and reported 1-year persistence probabilities between 18.4%Citation35 and 57.3%Citation38. As a result, our 1-year persistence probability of 21.1% is ranked about the 25th percentile in all available results from the six studies. We also conducted sensitivity analyses using a variety of permissible gaps; however, at the gaps of 45 and 60 days, our levels of persistence were still below those from other countries. These findings indicate that AD treatment users in Thailand may have not received adequate therapeutic benefits from AD medications.

Significant determinants of non-compliance and non-persistence

The combination treatment between one kind of ChEIs and memantine demonstrated a positive impact on compliance behavior of newly-treated AD patients. This finding is consistent with a large population-based study conducted in the Republic of Ireland, in which the co-prescription of AD treatment has been reported to almost double the time to treatment discontinuationCitation29. This finding is also in agreement with the most recent network meta-analysis of 142 studies comparing effectiveness of AD treatment, in which donepezil plus memantine has been found to be the most effective therapyCitation7. Synergistic effects of the combination treatment, which result in increased therapeutic benefits, could be a possible explanation for the better compliance and persistence behavior among AD treatment users.

On the other hand, the higher rates of non-compliance and non-persistence were found in the patients who were prescribed with AD treatment from the university-affiliated hospital. This type of hospital has been renowned for its proficiency of medical specialists, but it is situated in only a few major cities across the country. The major reason behind these higher non-compliance and non-persistence rates is probably due to the farther distance from patients’ residences to the university-affiliated hospital. In Thailand, to date, only tertiary hospitals where AD specialists are available are capable of prescribing AD medications. Generally, patients need to visit the outpatient department of their regular tertiary hospital every 2–16 weeks, dependent on the stage of the disease, in order to refill their AD medications. To allow the patients to refill AD treatment from a nearby non-specialized hospital, the World Health Organization’s Mental Health Gap Action Program (WHO’s mhGAP)Citation44 should be considered to put into action. This program provides evidence-based guidance enabling non-specialists to deliver psychosocial and pharmacological interventions for mental health conditions under the necessary supervision of specialists. Together with the fact that face-to-face interventions delivered by pharmacists are the most effective strategy in improving medication adherenceCitation45, nationwide hospital pharmacists are encouraged to get involved in the WHO’s mhGAP. After the program is successfully implemented, not only the AD patients but patients with other psychological disorders would gain benefits from the ease of access to mental health services, which potentially ameliorates the levels of compliance and persistence.

Another great concern has arisen when we found that the vast majority of Thai people were possibly inaccessible to AD treatment due to the inability to reimburse for the treatment costs. The lack of financial support was also significantly associated with the increased risk of early AD treatment discontinuation. Previous studies from HICs have found a similar possibility of socioeconomic barriers to AD treatmentCitation36,Citation41,Citation46,Citation47. Maxwell et al.Citation48 suggested that the worsened compliance and persistence may have been contributed from the increased out-of-pocket expenses with the sustained use of AD treatment along the course of the disease. As a consequence, to tackle with both limited accessibility and early treatment discontinuation issues, the expensive expenditure incurred by AD treatment should be considered to equitably cover all Thai citizens. Nonetheless, in order to facilitate the policy-maker’s ability to make such a decision, future full HTAs, assessing whether or not AD treatment is cost-effective and able to contribute considerable positive effects to the whole society, are warranted.

Strengths and limitations

An important strength of this study is that study subjects were identified from the databases of five hospitals located in different regions across the country, thus enhancing the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, since the diagnosis and prescription data have been documented as a part of routine practice by healthcare professionals, another strength is that recall bias is negligible. Nevertheless, the findings should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, although the hospital databases in Thailand have been evaluated as having a high level of validityCitation49, the possibility of random coding errors could not be excluded. This may lead to non-differential misclassification, resulting in under-estimation of the strength of the association findings. Second, we are unable to investigate other variables that may be associated with the levels of compliance and persistence such as cognitive status, functional ability, psychiatric symptoms, individual health behaviors, and healthcare system factorsCitation10,Citation48, for these variables have not been captured in the hospital databases. Finally, the retrospective analyses using prescription refills may over-estimate the levels of compliance and persistence, because it is difficult to validate whether or not the medications are actually taken after being refilled. However, it is reasonable to assume that the patients would not return to refill a prescription without the intention to comply or persist with the treatmentCitation13.

Conclusions

Our study applies the joint approach of compliance and persistence analyses to scrutinize the situation of compliance and persistence behavior among AD treatment users in Thailand. The somewhat inferior levels of compliance and persistence, when compared to other countries, serve a useful purpose in calling the attention of healthcare professionals and policy-makers to take action on the modifiable determinants to promote both compliance and persistence levels. Ultimately, these “real-world” findings not only make valuable contributions to future full HTAs of AD treatment in Thailand, but also represent themselves as the commencement of compliance and persistence study on AD treatment outside HICs.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

There is no sponsor involved in this study.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

CD has received honoraria for speaker’s bureaus from pharmaceutical companies in Thailand including Eisai, Novartis Janssen-Cilag, and BLH from 2007 to the present. The other authors have no conflict of interest to report. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Previous presentations

The abstract of this study was presented at the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR), September 2018, Tokyo, Japan.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the hospitals that provided databases for analysis in this study.

References

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World population ageing. New York: United Nations; 2015

- Prince M, Wimo A, Guerchet M, et al. World Alzheimer report 2015: the global impact of dementia: an analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI); 2015

- Prince M, Jackson J. World Alzheimer report. London, UK: Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2009

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013

- Wong CW. Pharmacotherapy for dementia: a practical approach to the use of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine. Drugs Aging 2016;33:451-60

- DiPiro J, Talbert R, Yee G, et al. Pharmacotherapy: a pathophysiologic approach. 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2015

- Tricco AC, Ashoor HM, Soobiah C, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of cognitive enhancers for treating Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and network metaanalysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66:170-8

- Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health 2008;11:44-7

- Johannsen P. Long-term cholinesterase inhibitor treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Drugs 2004;18:757-68

- Ku LE, Li CY, Sun Y. Can persistence with cholinesterase inhibitor treatment lower mortality and health-care costs among patients with Alzheimer’s disease? A population-based study in Taiwan. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dementias 2018;33:86-92

- El-Saifi N, Moyle W, Jones C, et al. Medication adherence in older patients with dementia: a systematic literature review. J Pharm Pract 2017:897190017710524

- Lam WY, Fresco P. Medication adherence measures: an overview. BioMed Res Int 2015;2015:217047

- Dezii CM. Persistence with drug therapy: a practical approach using administrative claims data. Managed Care 2001;10:42-5

- Aekplakorn W. The fifth national health survey of Thai population by medical examination. Nonthaburi: Health Systems Research Institute (HSRI); 2014

- Official Statistics Registration Systems. National population by age. Bangkok, Thailand: OSRS; 2015. Available at: http://stat.dopa.go.th/stat/statnew/upstat_age.php [Last accessed 23 December 2016]

- Prasat Neurological Institute. Clinical practice guideline: dementia. Bangkok: Prasat Neurological Institute; 2014

- Asia Pacific Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Policy note: Thailand health systems in transition. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (WHO); 2016

- Eddy D. Health technology assessment and evidence-based medicine: what are we talking about? Value Health 2009;12(Suppl 2):S6-S7

- Peterson AM, Nau DP, Cramer JA, et al. A checklist for medication compliance and persistence studies using retrospective databases. Value Health 2007;10:3-12

- World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems 10th revision (ICD-10). WHO; 2016. Available at: http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en [Last accessed 6 February 2018]

- Dilokthornsakul P, Chaiyakunapruk N, Nimpitakpong P, et al. The effects of medication supply on hospitalizations and health-care costs in patients with chronic heart failure. Value Health 2012;15(1 Suppl):S9-S14

- Herrmann N, Binder C, Dalziel W, et al. Persistence with cholinesterase inhibitor therapy for dementia: an observational administrative health database study. Drugs Aging 2009;26:403-7

- Le Couteur DG, Robinson M, Leverton A, et al. Adherence, persistence and continuation with cholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer's disease. Aust J Ageing 2012;31:164-9

- Ahn SH, Choi NK, Kim YJ, et al. Drug persistency of cholinesterase inhibitors for patients with dementia of Alzheimer type in Korea. Arch Pharm Res 2015;38:1255-62

- Gauthier S, Emre M, Farlow MR, et al. Strategies for continued successful treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: switching cholinesterase inhibitors. Curr Med Res Opin 2003;19:707-14

- Goel MK, Khanna P, Kishore J. Understanding survival analysis: Kaplan-Meier estimate. Int J Ayurveda Res 2010;1:274-8

- Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Multilevel and longitudinal modeling using Stata. 3rd ed. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2012

- Massoud F. Persistence with cholinesterase inhibitor treatment in Alzheimer’s disease. Can J Neurol Sci 2013;40:623-4

- Brewer L, Bennett K, McGreevy C, et al. A population-based study of dosing and persistence with anti-dementia medications. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2013;69:1467-75

- Riffenburgh RH. Statistics in medicine 2nd ed. Boston, US: Elsevier Academic Press; 2006

- Doody RS, Geldmacher DS, Gordon B, et al. Open-label, multicenter, phase 3 extension study of the safety and efficacy of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2001;58:427-33

- Mucha L, Shaohung S, Cuffel B, et al. Comparison of cholinesterase inhibitor utilization patterns and associated health care costs in Alzheimer’s disease. J Manag Care Pharm 2008;14:451-61

- Blais L, Kettani FZ, Perreault S, et al. Adherence to cholinesterase inhibitors in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:366-8

- Poon I, Lal LS, Ford ME, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in medication use among veterans with hypertension and dementia: a national cohort study. Ann Pharmacother 2009;43:185-93

- Haider B, Schmidt R, Schweiger C, et al. Medication adherence in patients with dementia: an Austrian cohort study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2014;28:128-33

- Borah B, Sacco P, Zarotsky V. Predictors of adherence among Alzheimer’s disease patients receiving oral therapy. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:1957-65

- Dybicz SB, Keohane DJ, Erwin WG, et al. Patterns of cholinesterase-inhibitor use in the nursing home setting: a retrospective analysis. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2006;4:154-60

- Kroger E, van Marum R, Souverein P, et al. Discontinuation of cholinesterase inhibitor treatment and determinants thereof in the Netherlands: a retrospective cohort study. Drugs Aging 2010;27:663-75

- Pariente A, Fourrier-Reglat A, Bazin F, et al. Effect of treatment gaps in elderly patients with dementia treated with cholinesterase inhibitors. Neurology 2012;78:957-63

- Bent-Ennakhil N, Coste F, Xie L, et al. A Real-world analysis of treatment patterns for cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine among newly-diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease patients. Neurol Ther 2017;6:131-44

- Amuah JE, Hogan DB, Eliasziw M, et al. Persistence with cholinesterase inhibitor therapy in a population-based cohort of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacoepidemiol drug Safety 2010;19:670-9

- Suh DC, Thomas SK, Valiyeva E, et al. Drug persistency of two cholinesterase inhibitors: rivastigmine versus donepezil in elderly patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs Aging 2005;22:695-707

- Bohlken J, Jacob L, Kostev K. Association between anti-dementia treatment persistence and daily dosage of the first prescription: a retrospective analysis in neuropsychiatric practices in Germany. J Alzheimer’s Dis 2017;58:37-44

- World Health Organization. mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press, World Health Organization; 2010

- Conn VS, Ruppar TM. Medication adherence outcomes of 771 intervention trials: systematic review and meta-analysis. Prevent Med 2017;99:269-76

- Saleh S, Kirk A, Morgan DG, et al. Less education predicts anticholinesterase discontinuation in dementia patients. Can J Neurol Sci 2013;40:684-90

- Tian H, Abouzaid S, Chen W, et al. Patient adherence to transdermal rivastigmine after switching from oral donepezil: a retrospective claims database study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2013;27:182-6

- Maxwell CJ, Stock K, Seitz D, et al. Persistence and adherence with dementia pharmacotherapy: relevance of patient, provider, and system factors. Can J Psychiatry 2014;59:624-31

- Lai EC, Man KK, Chaiyakunapruk N, et al. Brief report: databases in the Asia-Pacific region: the potential for a distributed network approach. Epidemiology 2015;26:815-20