Abstract

Aims: This study analyzed discrepancies in the quantity of medical services supplied by physicians under different payment systems for patients with different health statuses and illnesses by means of a field experiment.

Methods: Based on the laboratory experiment of Heike Hennig-Schmidt, we designed a field experiment to examine fee-for-service (FFS), capitation (CAP), and diagnosis-related group (DRG) payment systems. Medical students were replaced with 220 physicians as experimental subjects, which more closely reflected the clinical choices made by physicians in the real world. Under the three payment mechanisms, the quantity of medical services provided by physicians when they treated patients with different health statuses and illnesses were collected. Finally, relevant statistics were computed and analyzed.

Results: It was found that payment systems (sig. = 0.000) and patient health status (sig. = 0.000) had a stronger effect on physicians’ choices regarding quantity of medical services than illness types (sig. = 0.793). Additionally, under the FFS and CAP payment systems, physicians overserved patients in good and intermediate health while underserving patients in bad health. Under the DRG payment system, physicians overserved patients in good health and underserved patients in intermediate and bad health. Correspondingly, under FFS and CAP, the proportional loss of benefits was the highest for patients in bad health and the lowest for patients in good and intermediate health; while under DRGs, patients in good and intermediate health had the largest and smallest loss of benefits, respectively.

Limitations: In order to increase external effects of experiment results, we used the field experiment to replace laboratory experiment. However, the external effects still existed because of the blurring and abstraction of the parameters.

Conclusions: Medical treatment cost and price affected the quantity of medical services provided by physicians. Therefore, we proposed that a mix of payment systems could address the common interests of physicians and patients, as well as influence incentives from payment systems.

Introduction

By the end of 2017, China’s basic medical insurance had covered 1.1768 billion peopleCitation1, and become one of the largest healthcare systems worldwide. At the same time, China’s annual health expenditure increased sharply from 3.1662 trillion yuan in 2013 to 5.1598 trillion yuan in 20172, and the annual average growth rate reached 12.59% over 5 years. As the range of healthcare costs were covered and the level of insurance coverage increased, China’s government became more concerned about how its new medical payment system could be modified to use healthcare resources more efficiently. To identify the optimal payment system, various pilot payment systems were used in public hospitals in 200 pilot cities where a fee-for-service (FFS) payment system has been dominantCitation3. Additionally, since 2011, payment systems, such as diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) and capitation (CAP), have been included in local governments’ lists of possible healthcare payment systems. At present, in order to explore the payment method, the most suitable for China's national conditions, China has implemented a parallel payment system with multiple payment methods. Especially in the beginning of 2018, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security of the People’s Republic of China announced 130 payment standards for DRG. Under the guidance of this document, most provinces refined catalogues of payment standards by DRG in line with local health conditions. Taking Jiangsu Province as an example, it has formulated a detailed reform plan, including that more than 150 kinds of DRG should be developed and fulfilled in each urban area, and detailed operational rules for Changzhou, Nanjing, and other pilot areas.

Payment systems had a multidimensional impact on medical insurance expenditures. This research focused on the influence of payment systems about the quantity of medical services provided by physicians. Échevin and FortinbCitation4 found that reforming a payment system could affect physician behavior, in that the variety of medical options provided by physicians changed remarkably under different systems. Some laws had been confirmed by laboratory experiments in some countries, such as the finding that FFS provided physicians with an incentive to deliver more medical servicesCitation5. In contrast, under the CAP payment system, physicians might deliver fewer medical services because they received a fixed payment for each patientCitation6,Citation7. In addition, several studies had shown that medical services (for example, nursing and examinations) paid for the insurer through CAP cost more than that through FFS8. Recently, however, some researchers have obtained different results after conducting a laboratory experiment controlled for irrelevant variables. The irrelevant variables referred to the factors may affect subjects’ decisions, while they were not independent variables and dependent variables in the experiment. The results showed that, under FFS, CAP, and DRGs, the quantity of medical services provided by physicians failed to achieve the predicted amount. Intrinsic motivators such as incentives was an important factor in the quantity of medical services provided by physicians. Thus, the goal of healthcare reform should increase the economic benefits to physicians in order to improve patient healthcareCitation9. However, external stimuli such as payment systems and performance assessments only had a limited effect on healthcare quality and quantityCitation10. Moreover, a compensation incentive system was essential to ensure that an adequate quantity of healthcare was provided. SchmitzCitation11 used representative health-related data on German families from 1995–2002 to determine how payment system reform impacted patients’ budgets indirectly by varying the amount of medical services.

Additionally, Chinese scholars found that, without an incentive to provide a greater quantity of medical services, physicians served their own self-interest under FFS by reducing their workloadsCitation12. Both in theory and in practice, physicians avoided severely ill patients, preferring to perform medical services that resulted in higher rewards, and preferring patients with lower treatment-related risks and paying more attention routinely to disease prevention under CAP13. Although DRGs theoretically encouraged physicians to provide moderate levels of medical services, their popularization was challenged by both the complexity of classifying diseases and the DRG fee system. The DRG-based payment system had resulted in reducing intensity of care and shortened length of stay, which meant that both the quality and quantity of medical services had declinedCitation14.

This paper has studied the effects of different medical payment systems, using a laboratory experiment that was usually employed in behavioral studies. Compared to experiments performed in a natural environment, laboratory experiments were different because the dependent variables could be accurately observed when irrelevant variables were controlled and independent variables were used according to a planCitation15. In 1962, the “Double Auction Mechanism” experiment of Vernon L. Smith transformed experimental economics into an independent disciplineCitation16. In research fields, such as game theoryCitation17, public administrationCitation18,Citation19, and industrial organizationCitation20, controlled laboratory experiments had become essential. In experimental economics, they had become commonplace. Since 2002, when Vernon Smith, the “Father of Experimental Economics”, won the Nobel Prize in Economics, laboratory experiments, which were accepted by the mainstream economics community, gained popularity quickly. Recently, laboratory experiments have been gradually applied to health economics studies. For example, Hennig-Schmidt et al.Citation21 used this technique for early behavioral research on physicians’ provision of medical services. GodagerCitation22 used data from a laboratory experiment performed by Hennig-Schmidt et al.Citation21 to analyze the heterogeneity of physician altruism, and conducted a regression analysis on those data to determine the relationship between choosing medical options out of self-interest and choosing medical options to benefit the patient. Another work was that of CharnessCitation23, who reclassified various types of experiments and showed how to use them for healthcare research. Based on psychology and sociology theories, DjawadiCitation24 developed a framework of experimental research to identify behavioral changes during the medical treatment process. The same method was used to analyze comparisons between medical and non-medical students. The authors investigated motives for delivering medical care. They concluded that non-medical students were less likely than medical students to sacrifice their profits to benefit patient healthCitation25.

We used a field experiment study design to examine the behaviors of physicians. If a laboratory experiment were performed instead of a field experiment, the conclusions might not be valid due to hyper-abstraction and simplificationCitation26. However, the participants in a field study were not restricted to college students, instead, they were adults in society. Moreover, the experimental environment was not confined to a laboratory. A field experiment, as defined by Harrison and ListCitation27, was an experiment conducted in multiple locations, including laboratories and actual environments. Its participants included both students and non-college adults. Therefore, under the real social conditional, the experiment subjects could make realistic choices. Above all, because of the differences between the experimental environment and subjects, the field experiment could represent actual conditions in a real environment, and subjects might act instinctively as they do in daily life, increasing the external validity of resultsCitation28.

In this study, we performed a laboratory experiment based on the work of Hennig-SchmidtCitation5, with the modification of two elements. Instead of sampling medical students, we improved externality by asking physicians to participate. Additionally, because DRGs were the favored payment system in China, we included them in our comparison groups. Therefore, this study used a field experiment to analyze and compare how incentives from the FFS, CAP, and DRG payment systems influenced the quantity of medical services provided by physicians. Furthermore, we determined which payment system was optimal for China.

Experimental design and procedure

Sampling

Our research used simple random sampling to select practicing physicians as subjects. A total of 220 physicians were selected from among 5,689 practicing assistant physicians at 10 public hospitals in Nanjing, Jiangsu, China. We chose public hospitals for three reasons. First, 42.78% of Chinese hospitals were public hospitals in 2016; second, there were 2.85 billion visits to public hospitals in 2016, accounting for 87.2% of total hospital visits; and, finally, the three studied payment methods were widely used in public hospitals. We required the participants to select medical interventions based on their own health and disease status; such selections represented physicians’ choices in an actual working environment.

Experimental materials and parameters

Tools

Our research built on research conducted in a laboratory setting and used parameters of disease diagnosis and medical treatment quantity in hospitals identified. In addition, questionnaires were designed to simulate a laboratory environment and complicated medical conditions.

This study presented five illnesses (K = A, B, C, D, and E) to physicians working under conditions with FFS, CAP, and DRG payment systems. Patients’ health was denoted using the variable J, which included three levels of health: good, intermediate, and bad. Therefore, there were 15 possible decisions for each payment method. showed the results when patients were in good health and had disease A.

Table 1. FFS (K = A, J = 1).

The first two columns of show the quantity of medical care provided and the medical services provided, denoted A1–A10. The third column shows the charge for treatment, Rjk(q). Column 4 shows physicians’ treatment cost, Cjk(q). The fifth column shows the benefit to the physicians, πjk(q). The final column shows the benefit to the patients, Bjk(q). Quantity choice, Q, varied according to patients’ level of health and physicians’ interest in treating the patient, πjk(q), which could take values of 0–10 from the first column.

Variables and parameters

FFS, CAP, and DRGs were chosen for this study because they were likely to be the payment systems that will be used in China in the future.

Five types of illnesses were selected and denoted by the variable K. After reviewing the literature and collecting information, we requested opinions from physicians who screened for five common diseases with high morbidity K (K–A, B, C, D, and E) under DRGs. The five diseases were only used to calculate parameters, and five types of illnesses were replaced by K in the questionnaire. The physicians did not know the illnesses’ details. As a result, we selected five diseases according to the following principles: first, under the DRG payment system in China, there were clear standards for treatment costs; second, patient health state was easy to categorize using these diseases; third, the effect of treatment was relatively significant for these diseases. The variable “A” denoted femoral shaft fracture; “B” denoted ureteral calculus; “C” denoted acute simple appendicitis; “D” denoted varicose veins in a lower limb; and “E” denoted gastroduodenal ulcer. The physicians just decided the quantity of the medical services, and they did not have to diagnose the conditions.

A patient’s disease level, i.e. his or her level of health (denoted by the variable J) for the five diseases was determined by expert consensus according to Chinese clinical diagnostic guidelines.

The optimal quantity of patient treatments, which was denoted by the variable q*jk, yielded the greatest benefit to a patient in state j for illness k (j ∈ {1,2,3}, k ∈ {A,B,C,D,E}). The patient’s optimal quantity of medical interventions were as follows: q*1k = 3, q*2k = 5, and q*3k = 7 for patient types 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The average quantity of patient treatment, which was denoted by the variable qjk, was represented in the figures as ‘qjk. The categories for the quantity variable were also determined using the Delphi method.

The amount of deviation of actual services from the optimal values denoted by the variable D can be calculated by using the following equation: D = (qjk-q*jk)/q*jk. Experimental results were denoted by D, which represented the extent to which the average quantity of medical services provided by physicians departed from the optimal quantity, q*jk, for different health levels and illness types to compare the extent of disparities among physician behaviors under the three payment systems.

Treatment charge, Rjk(q), varied among payment systems. Under the CAP system, payment was a fixed, lump sum equal to the charge determined by the medical insurance provider in the capital city of Nanjing, China. In contrast, fees for medical care under FFS, as the name suggests, were charged according to the price of the medical service to treat the type of disease at issue. Therefore, the fees varied. DRGs provided the standards, and determined payment by considering both the disease and the patient’s level of health.

The treatment cost Cjk(q) for the optimal treatment quantity was paid through using a virtual currency, Taler. The exchange rate was 1 Taler = ¥100. The following formula was used to calculate Cjk(q): Cjk(q) = (((Cjk(q*jk) /q*jk) × q)/10. Therefore, treatment costs increased as the quantity of medical services increased.

Physician benefit πjk(q) was equal to the payment amount minus the cost and was calculated as follows: πjk(q) = Rjk(q) – Cjk(q). In addition, the value of the optimal patient benefit was given in units of 10 and was determined by the Delphi method.

The degree of the loss of health benefits to the patient was denoted by the variable Ljk(q), which was calculated as follows: Ljk(q) = (B(qjk*) – B(qjki))/B(qjk*). The difference between the benefit of the patient under the optimal treatment quantity and the benefit of the patient under the actual quantity of medical services supplied by physician ratios the optimal benefit of the patient which is the health loss degree of the patient.

We used the aforementioned parameters to design questionnaires and perform the experiment.

Experimental protocol

Preparations

Voluntary agency contact: We contacted volunteer organizations, explained the research purposes, and signed mutual agreements. Physicians’ choices about the quantity of medical services to provide had real-world consequences for patients. The money corresponding to benefits provided to fictitious patients was donated to charities for real patients.

Physician recruitment: Based on the long-time cooperation with hospitals in Nanjing, before the experiment, we contacted deans of the hospitals, and mobilized physicians to participate in the experiment. We selected physicians through simple random sampling, explained the experimental goals and their importance, described the experimental procedures and method used for collecting physician benefits, and signed the implementation protocol.

Data collection training: We recruited 40 medical students to volunteer to gather data through the method taught to them by the researchers. The content of the experiment, definitions of variables, and problems addressed by the experiment were explained to ensure a comprehensive understanding and the correct execution of the experimental procedures.

Experimental operations

Research group leaders contacted hospitals and schedule experiments. After completing their procedural training, the medical students were randomly assigned to 10 groups: Four students in each group arrived at the designated hospitals at a prescribed time. Next, the students and physicians met in hospital meeting rooms, where volunteers would explain the elements of the questionnaires and answer questions. The topics which were explained included the three payment systems, the range of the quantity of medical service choices, the definitions of variables (e.g. treatment cost and physician and patient benefits), and the physicians’ treatment options for each illness and level of health. Medical student volunteers, who were grouped according to the payment system for which they were responsible, would ask subjects three test questions to verify that the subjects understand the tasks.

After the above explanation, physicians completed the questionnaires for the experiment. In the questionnaires, the physician made 15 decisions about the quantity of medical services to provide. As a result, in the three payment systems, every physician needed to make 45 possible choices regarding the quantity of medical services provided to fictitious patients. The order in which physicians participated in the three payment schemes was random, and physicians can’t choose their payment system. Sessions lasted ∼1.5 h, during which filling out the survey (every treatment decision) cost 1–3 min.

After the experiment, student volunteers recorded the treatment choices regarding the quantity of medical services provided by the physicians. We converted the quantities of medical services and experimental variables into treatment funds and donated this amount to a previously contacted charitable organization. To increase the experiment’s authenticity, subjects were paid an amount based on their experimental choices via a bank transfer to their hospital work accounts 3 weeks after the experiment.

Ethical considerations

Our study was a laboratory experiment in an artificial setting: patients were not involved. The physicians’ answers to questionnaire items and their identities were confidential pursuant to the agreement that they signed. In addition, the treatment funds and physicians’ monetary incentives were financed by the research project. Therefore, there was no financial incentive for the experimenters.

Data processing

Because of the large volume of questionnaires, we sorted them by payment system. Six researchers (two per payment system) entered the data, collated the data, and analyzed the reliability and validity of the data. Then we computed and analyzed relevant statistics, such as the deviation between patients’ degrees of health benefit loss, the optimal quantity of medical services, and the results of a test of significance.

Results

In total, 209 physicians signed the agreement and participated in the experiment. They completed 9,045 questionnaires that included the three payment systems. The exclusion of invalid questionnaires through data auditing resulted in 8,550 valid questionnaires. The questionnaires had a 94.53% response rate. The criteria for excluding invalid questionnaires were as follows: first, obviously unreasonable choices, such as 10 units of medical services for a mild condition; second, completely uniform choices, such as the same 45 choices for patients with different conditions and disease types in the three payment systems; and, third, incomplete questionnaires.

We calculated a value of Cronbach’s α equal to 0.943 (> 0.8), which confirmed the reliability and validity of the questionnaire. Hospital and physician sampling and the number of collected and valid questionnaires are shown in .

Table 2. Sample of physicians and numbers of collected questionnaires.

Quantity of medical services provided

Physicians provided the lowest quantity of medical care under DRGs, and the highest quantity of medical care under FFS. In addition, there were significant differences in the quantity of medical services provided by the three systems. Physicians provided the lowest quantity of medical services when patients were in good health, and they provided the highest quantity of medical services when patients were in bad health; this difference was significant. Physicians treating illness E provided the greatest quantity of medical services. Unlike the aforementioned classifications, there was no significant difference in the quantity of medical services provided among the five illnesses. The results are shown in .

Table 3. Quantity of medical services provided by physicians under different payment systems.

Table 4. Influences of FFS and CAP on physicians’ provision of medical services for patients with the same level of health.

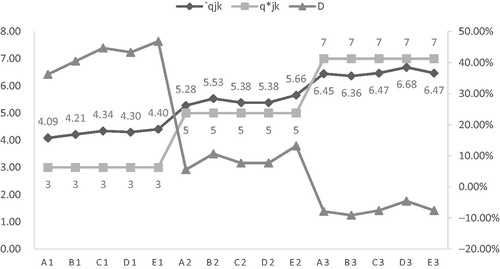

Comparisons between physicians’ quantity choices and patients’ optimal quantity under FFS

Tests of the significance of the 15 conditions showed that there were marked differences between a physician’s choice of the quantity of medical services provided and the quantity that was optimal for the patient. For mild or moderate illnesses, physicians tended to provide more medical services than the optimal quantity for the patient, as shown in . When the patient was in good health, the difference D increased. In addition, for patients in bad health, the average quantity of medical services provided by physicians was lower than the optimal quantity. Thus, physicians under-provided medical care when the patient was in bad health.

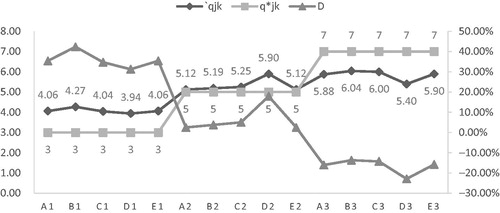

Comparisons between physicians’ quantity choices and patients’ optimal quantity under CAP

Similar to FFS, the CAP system resulted in significant differences in the quantity of medical services provided when the patient’s level of health was considered. For the five illness types, the average quantity of medical services provided was greater than the patient’s optimal quantity when the patient was in good or intermediate health. In contrast, the opposite was observed when patients were in bad health. As shown in , the greatest deviation was for mild and severe illnesses.

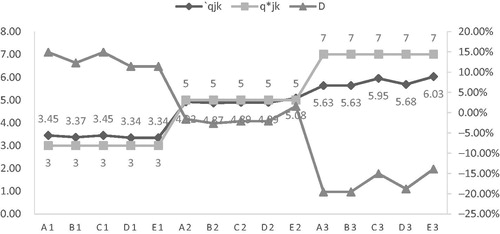

Comparisons between physicians’ choices regarding the quantity of medical services provided and patients’ optimal quantity of medical services under DRGs

In contrast to the aforementioned payment systems, under DRGs, the average quantity of medical services provided was greater than the optimal quantity for patients in good health. Physicians tended to under-serve patients in intermediate or bad health. There was a significant difference in the quantity of medical services provided to the three levels of health. As shown in , the disparity between the average and optimal quantity of health services provided was highest for severe illnesses, lower for mild illnesses, and lowest for moderate illnesses.

Impact of FFS and CAP on the quantity of medical services provided by physicians to patients with a given level of health

As observed in above, the trends in physicians’ provision of medical care under FFS and CAP for patients with the same level of health were similar. Therefore, we investigated whether different payment systems had created significant differences for patients with the same level of health. A data analysis revealed that, for the three levels of health, there was no significant difference in medical service quantity between FFS and CAP.

Comparisons of patients’ loss of health benefits

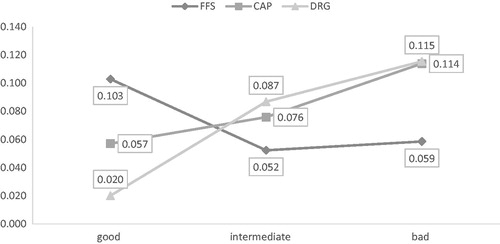

Influence of payment systems on the degree of patients’ loss of health benefits

Next, we investigated how patient health had been affected by payment systems by examining physicians’ medical provision behavior. As shown in , the degree of the loss of health benefits to the patient varied under the three payment methods for patients with the same level of health. Patients in good health experienced the largest loss of health benefits under FFS and the smallest loss of health benefits under DRGs; these results were significantly different. Patients in intermediate health experienced the largest loss of health benefits under DRGs and the smallest loss of health benefits under FFS. Again, the results showed significant differences. Patients in bad health lost more health benefits under DRGs and CAP, but fewer under FFS. Again, the results showed significant differences.

Effects of health status on patients’ loss of health benefits

Under the three payment systems, a patient’s level of health had a varying impact on the patient’s loss of benefits, as shown in . Under FFS and CAP, the proportional loss of benefits was the highest for patients in bad health and the lowest for patients in good or intermediate health. Under DRGs, patients in good health had the largest loss of benefits, patients in bad health had a smaller loss, and patients in intermediate health had the smallest loss. Therefore, we found that the three health statuses had resulted in notable differences under the three payment systems.

Table 5. Impacts of patient health status on loss of health benefits under the same payment system.

Impact of illness type on the quantity of medical services provided by physicians under DRGs

Next, we focused on how illness type influenced the quantity of medical services provided by physicians under DRGs. In DRGs, illness types were important for classifying diseases into groups for determining service fees and for cost accounting. We assumed that all patients had the same level of health and analyzed the quantity of medical services provided by physicians for patients with illnesses A, B, C, D, and E. The results, which are shown in , indicated that, for patients in good, intermediate, and bad health, the results of the significance test were 0.95, 0.82, and 0.30, respectively, across the five diseases. Therefore, illness type did not correlate with the quantity of medical care provided to a patient in a given state of health.

Table 6. Quantity of medical services provided by physicians for patients with different illnesses and with the same health status.

Discussion

Effects of incentives from payment systems on the quantity of medical services provided by physicians

The experimental data showed significant differences among the three payment systems, reflecting the strong influence of the payment system on physician behavior.

The results of the analysis showed that, under FFS and CAP, physicians overserved patients in good and intermediate health, but underserved patients in bad health. By examining treatment cost data, we concluded that physicians’ decisions were motivated by benefits not only to themselves, but also to their patients.

Under FFS, for a patient in bad health, the increase of the economic benefits of doctors and the health benefits of patients were limited for the increase of the quantity of medical services when the quantity of medical services exceeded the optimal quantity (7 units). For instance, the physician’s treatment cost and profit increased by 1.50 and 0.12, respectively, and the patients had a large loss of health benefits, when the quantity of medical services provided by the physician exceeded the optimal quantity of 7 by one unit. At the same time, with the increase of the quantity of medical services, the patient’s financial burden was getting heavier. Considering the patient's economic and health benefits, physicians made rational choices. However, for patients in good or intermediate health, physicians earned considerable profits and patients had minimal loss of health benefits when the quantity of medical services provided was higher than the optimal quantity.

In contrast, under CAP, patients in good and intermediate health experienced a health benefit of 1.5 and 7.0, respectively, when the quantity of medical services provided by physicians was one unit less than the optimal quantity. Additionally, the health benefit for patients in good and intermediate health was 9.5 when physicians’ profits were –1.2 and –2.0, respectively. Patients in bad health experienced a 0.45-fold greater loss of health benefits when physicians provided one unit of medical services more than the optimal quantity. This created a win–win situation in which small losses of patient benefits resulted in a 1.3-fold increase in physicians’ profits. In summary, physicians weighed their profits against the health benefits to the patient and made rational decisions when delivering medical services. DRGs will be discussed in more detail below.

According to the results described above, there was no significant difference between FFS and CAP. The reason for this may be related to the Chinese health system. The FFS payment system has been the standard in China for ∼40 years. Doctors may still choose a service model similar to FFS, due to its familiarity. In recent years, however, China has promoted and implemented the DRG payment system, which was expected to replace FFS as the standard system in the future; this had a great influence on doctors’ actual behavior. Overall, when the results presented above were considered in light of the background of the Chinese health system, there were significant differences among the three payment systems, and the payment mechanism had a remarkable impact on the behavior of doctors.

Effects of payment systems on patient health benefits

As shown above, payment systems had diverse effects on the loss of patient benefits. For example, for patients in good health, the loss of benefits was the greatest under FFS, and was significantly different from that under the other payment systems. Unlike physician behavior under CAP and DRGs, physicians under FFS preferred to provide more medical services, thus increasing their income. Therefore, they met their profit goals and guaranteed health benefits to their patients. This showed that FFS provided a considerable incentive for the over-provision of medical services. For patients in intermediate or bad health, DRGs resulted in greatest loss of patient benefits, CAP resulted in second-greatest loss, and FFS resulted in third-greatest loss. This implied that DRGs failed to ensure sufficient medical services for patients in bad health.

By evaluating both patients’ health benefits and the practices resulting from China’s three payment systems, we found that CAP and FFS matured and became more adaptable to physicians’ needs over the long term. Under CAP, physicians avoided treating severely ill patients when their conditions deteriorated gradually. In contrast, under FFS, the more medical services physicians provided, the greater the benefit both to physicians and to patient health. Finally, the popularization of DRGs was impeded by the complex nature of disease classification and measurement of the quantity of health services provided. Moreover, DRGs had drawbacks when patients’ illnesses became more severe.

Impact of health status on the quantity of medical services provided by physicians

We explored how health status affected the loss of health benefits to the patient and determined that the severity of an illness had a statistically significant impact on the loss of benefits. This finding accounted for the fact that patient health was a primary consideration in the quantity of health services provided by a physician.

Influence of DRGs on the quantity of medical services provided by physicians

The data showed that, under DRGs, illness types slightly influenced medical service quantity for patients with all three health statuses. We proposed the following reasons for this finding. First, this finding might be attributable to China’s poor disease classification and illness grouping. This flaw could be unobservable with patients in good health while creating disadvantages for patients in bad health. Although DRGs typically limited healthcare to managing a single disease, severe diseases featured complex conditions and complications universally. Consequently, the difficulty of classifying a disease, judging the severity of an illness, and setting the standard for medical services resulted in controversy. If DRGs were implemented while the system was immature, patients would experience a greater loss of health benefits. Another concern was that, when physicians’ profits were no longer linked to the quantity of medical services provided, physicians required additional sources of motivation to provide a high quantity of health services. Without suitable motivation in the form of economic compensation or other benefits, physicians would under-serve patients, minimizing treatment costs in an effort to maintain their own benefits.

Comparison of the findings in this study with findings in the existing literature

Our findings were in accordance with the following conclusions of other scholars. Hennig-Schmidt et al.Citation29 asserted that medical decisions were influenced by both physicians’ profits and health benefits to the patient. In a study performed by GreenCitation30, incentive was an important factor in treatment decisions, because of the role of the crowding-out effect in payment systems. The heterogeneity of altruism was the focus of a study by Godager and WiesenCitation31, in which the method physicians used to measure self-interest and patient benefits varied under different payment systems. Additionally, the authors asserted that the single payment method, such as only FFS, would not result in the optimal quantity of health services. The research of Van Herck et al.Citation32 showed that physicians preferred payment systems that increased their benefits. Thus, it would be challenging to reform a payment system that did not reward the work of physicians. In addition, a study found that, in Germany, physicians had strong negative reactions to a payment system and adjusted to it by altering the means of payment by patientsCitation33. In contrast to the results of the present research, several earlier studies found no connections between payment incentives and the quantity of health services provided, concluding that the payment system had no influence on physicians’ provision of medical careCitation34,Citation35.

Innovations and limitations

This study was different from earlier studies in two ways. First, it was the first field experiment to study the medical services payment system in China and to examine physicians’ internal motivation for providing a higher quantity of health services. This result facilitated research into controlling medical expenses through the reform of payment systems. Second, instead of recruiting medical students as participants, we recruited physicians both to eliminate peer pressure and to obtain results in an actual medical care environment, strengthening the study’s reliability. Incorporating real people into a field experiment, which was distinct from the laboratory experiment conducted by Hennig-SchmidtCitation5, prevented the loss of authenticity caused by over-abstraction, thus increasing the external effect of this study. Despite this modification, our research would prompt discussions of its low replicability and externality. To address this bias, we controlled the variables during data collection and simulated a real environment to the greatest extent possible, ensuring the study’s validity and reproducibility.

This study had the following limitations. First, we concluded that variations in results were unavoidable based on the differing responses to the questionnaire items. Although both the contents of the experiment and confidentiality were explained and guaranteed, after removing invalid surveys, we found that several participants had selected responses based on their moral beliefs, for example, by choosing the optimal quantity of health services for all items. This consequence of the research method did not accurately reflect physicians’ choices related to the quantity of health services when they encountered different types of patients in practice, resulting in experimental inaccuracy. Additionally, the study was limited geographically. External effects that existed before the experiment were increased because of the blurring and abstraction of the parameters, which included the experimental setting and existing national healthcare payment systems. To counter this, we sampled only physicians from Grade-A tertiary hospitals in Nanjing, China, and used data to determine typical medical service fees, payment per patient and the price of each illness in Nanjing, China, potentially decreasing the external effect.

Conclusion

Based on this empirical study, we concluded that both medical service payment systems and patient health status influenced physicians’ choice of the quantity of medical services provided. Moreover, we concluded that medical service payment methods varied in their effects on both the quantity of medical services provided and the benefits to patient health. Under the FFS and CAP payment systems, physicians over-served patients in good and intermediate health while they under-served patients in bad health. Under the DRG payment system, physicians over-served patients in good health and under-served patients in intermediate or bad health. Additionally, illness type did not result in a significant difference in the quantity of medical services provided. Under DRGs, the average quantity of medical services provided by physicians was almost equal to the optimal quantity for the patient.

We investigated how and why payment systems and patient health status influenced the quantity of medical services provided by physicians and found that the primary determinants of the quantity of medical services provided were how much the physicians would profit and the health benefits to the patient. After controlling for patient health benefits, we found that medical treatment cost and price affected the quantity of medical services provided by physicians. From this research, we concluded that requiring a set payment created problems in the execution of a payment system. Therefore, we recommended a mix of payment systems based on hospital characteristics and patients’ level of health to optimize the benefits to both patients and physicians. Future reforms should appropriately leverage the effect of incentives to transform physicians and patients into parties with a common interest instead of creating opponents with conflicting goals.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This manuscript is supported by “Double First-Class” University project (CPU2018GY39) in China Pharmaceutical University. The research funding for this study is from educational institutions that had no interests associated with this research.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The authors have no financial or other relationships to disclose. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this manuscript acknowledge that this article could not have been finished without the help of the medical institutions, doctors, and experimental data collection and processing staff who participated in the experiment. Special tribute is also paid to the professionals who provided advice and criticism on this paper for their valuable suggestions that further perfected this paper.

References

- The State Council the People’s Republic of China. Human resources and social security development statistical bulletin in 2017 [EB/OL]. Beijing, China. Available at: http://www.mohrss.gov.cn/ghcws/BHCSWgongzuodongtai/201805/t20180521_294290.html,2018-05-21/2018-07-14

- The State Council the People’s Republic of China. Statistical bulletin on the development of health care in China in 2017 [EB/OL]. Beijing, China. Available at: http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/guihuaxxs/s10743/201806/44e3cdfe11fa4c7f928c879d435b6a18.shtml,2018-06-12/2018-07-14

- Gao C, Xu F, Liu GG. Payment reform and changes in health care in China. Soc Sci Med 2014;111:10–16

- Échevin D, Fortinb B. Physician payment mechanisms, hospital length of stay and risk of readmission: evidence from a natural experiment. J Health Econ 2014;36:112–24

- Hennig-Schmidt H, Selten R, Wiesen D. How payment systems affect physicians’ provision behaviour—an experimental investigation. J Health Econ 2011;30:637–46

- Ellis RP, McGuire TG. Provider behavior under prospective reimbursement: cost sharing and supply. J Health Econ 1986;5:129–51

- Frank RG, Glazer J, McGuire TG. Measuring adverse selection in managed health care. J Health Econ 2000;19:829–54

- Allard M, Jelovac I, Léger PT. Treatment and referral decisions under different physician payment mechanisms. J Health Econ 2011;30:880–93

- Yang J. Wage reforms, fiscal policies and their impact on doctors’ clinical behaviour in China’s public health sector. Policy Soc 2006;25:109–32

- Green EP. Payment systems in the healthcare industry: an experimental study of physician incentives. J Econ Behav Org 2014;106:367–78

- Schmitz H. Practice budgets and the patient mix of physicians – the effect of a remuneration system reform on health care utilization. J Health Econ 2013;32:1240–9

- Mao Y, Chen G. Economic analysis of the payment mechanism of medical insurance. Mod Econ Sci 2008;4:99–104, 128

- Xie C-Y, Hu S-L, Sun G-Z, et al. Exploration and experience of provider payment system reform in China. Chin Health Econ 2010;5:27–9

- Cheng S-H, Chen C-C, Tsai S-L. The impacts of DRG-based payments on health care provider behaviors under a universal coverage system: a population-based study. Health Policy 2012;107:202–8

- Levitt SD, List JA, Reiley DH. What happens in the field stays in the field: exploring whether professionals play minimax in laboratory experiments. Econometrical 2010;78:1413–34

- Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 1979;47:263–91

- Simon HA A behavioral model of rational choice. Q J Econ 1955;1:343

- Bozeman B, Scott P. Laboratory experiments in public policy and management. J Public Admin Res Theory 1992;2:293–313

- Bozeman B. Experimental design in public policy and management research: introduction. J Public Admin Res Theory 1992;2:440–2

- Kanazawa S. Testing macro organizational theories in laboratory experiments. Soc Sci Res 1999;28:66–87

- Hennig-Schmidt H, Selten R, Wiesen D. How payment systems affect physicians’ provision behavior – an experimental investigation. J Health Econ 2011;30:637–46

- Godager G. Profit or patients’ health benefit? Exploring the heterogeneity in physician altruism. J Health Econ 2013;32:1105–16

- Charness G. Experimental methods: extra-laboratory experiments-extending the reach of experimental economics. J Econ Behav Org 2013;91:93–100

- Djawadi BM. Conceptual model and economic experiments to explain nonpersistence and enable mechanism designs fostering behavioral change. Value Health 2014;17:814–22

- Hennig-Schmidt H, Wiesen D. Other-regarding behavior and motivation in health care provision: an experiment with medical and non-medical students. Soc Sci Med 2014;108:156–65

- Plott CR. Industrial organization the theory and experimental economic. J Econ Lit 1982;20:1485–527

- Harrison GW, List JA. Field experiments. J Econ Lit 2004;42:1009–55

- Lucking-Reiley D. Using field experiments to test equivalence between auction formats: magic on the internet. Am Econ Rev 1999;89:1063–80

- Hennig-Schmidt H, Selten R, Wiesen D. How payment systems affect physicians’ provision behaviour—an experimental investigation. J Health Econ 2011;30:637–46

- Green EP. Payment systems in the healthcare industry: an experimental study of physician incentives. J Econ Behav Org 2014;106:367–78

- Godager G, Wiesen D. Profit or patients’ health benefit? Exploring the heterogeneity in physician altruism. J Health Econ 2013;32:1105–16

- Van Herck P, Kessels R, Annemans L, et al. Healthcare payment reforms across western countries on three continents: lessons from stakeholder preferences when asked to rate the supportiveness for fulfilling patients’ needs. Health Policy 2013;111:14–23

- Schmitz H. Practice budgets and the patient mix of physicians – the effect of a remuneration system reform on health care utilization. J Health Econ 2013;32:1240–9

- Gosden T, Forland F, Kristiansen I, et al. Impact of payment method on behavior of primary care physicians: a systematic review. J Health Serv Res Policy 2001;6:44–54

- Sørensen R, Grytten J. Service production and contract choice in primary physician services. Health Policy 2003;66:73–93