Abstract

Aim: To assess the cost-effectiveness of interleukin (IL)-17A inhibitor secukinumab vs the currently licensed biologic therapies in ankylosing spondylitis (AS) patients from a Canadian healthcare system perspective.

Methods: A decision analytic model (semi-Markov) evaluated the cost-effectiveness of secukinumab 150 mg compared to certolizumab pegol, adalimumab, golimumab, etanercept and etanercept biosimilar, and infliximab and infliximab biosimilar in a biologic-naïve population, over 60 years of time horizon (lifetime). The Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI 50) response rate was used to assess treatment response at week 12. Non-responders or patients discontinuing initial-line of biologic therapy were allowed to switch to subsequent-line biologics. Model input parameters (short-term and long-term changes in BASDAI and Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index [BASFI], withdrawal rates, adverse events, costs, resource use, utilities, and disutilities) were obtained from clinical trials, published literature, and other Canadian sources. Benefits were expressed as quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). Cost and benefits were discounted with an annual discount rate of 1.5% for all treatments.

Results: In the biologic-naïve population, secukinumab 150 mg dominated all comparators, as patients treated with secukinumab 150 mg achieved the highest QALYs (16.46) at the lowest cost (CAD 533,010) over a lifetime horizon vs comparators. In the deterministic sensitivity analysis, results were most sensitive to changes in baseline BASFI non-responders, BASDAI 50 at 3 months and discount rates. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis showed that secukinumab 150 mg demonstrated higher probability of achieving maximum net monetary benefit vs all comparators at various cost thresholds.

Conclusions: This analysis demonstrates that secukinumab 150 mg is the most cost-effective treatment option for biologic-naïve AS patients compared to certolizumab pegol, adalimumab, golimumab, etanercept and etanercept biosimilar, and infliximab and infliximab biosimilar for a lifetime horizon in Canada. Treatment with secukinumab translates into substantial benefits for patients and the healthcare system.

Introduction

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is an axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) that primarily affects the spine (debilitating inflammation of the sacroiliac joints). AS also affects peripheral joints, and enthesesCitation1 and extra-articular manifestations are also observedCitation2–4. Inflammation of sacroiliac joints can lead to progressive worsening pain, fatigue, stiffness, poor health-related quality-of-life, discomfort, and eventual progression to fusion (ankylosis) of the inflamed spinal joints, reducing spinal mobilityCitation5,Citation6.

Globally the prevalence of AS ranges from 10 per 10,000 to 140 per 10,0007,Citation8, with a prevalence in Canada of 60 per 10,000 in 20099. Clinical, humanistic, and economic burden of AS is significantCitation10. In 2003, mean annual costs per AS patient was Canadian Dollar (CAD) 9,008 in Canada, with direct healthcare accounting for 29% of these costsCitation11.

As per the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS) and European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the first line treatment for AS, while biologic therapies, such as the anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNFs), like etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, and golimumab, and the IL-17A inhibitor secukinumab are recommended in patients with persistently high disease activity, despite conventional treatments. If the initial biologic therapy fails, it is recommended to switch to secukinumab (level of evidence 1b) or a second anti-TNF (level of evidence 2)12. The 2016 updated recommendations also include a new overarching principle that the disease and its treatment are associated with high costs, and the cost of treatment should be considered while deciding on the treatmentCitation12. The Canadian Rheumatology Association (CRA)/Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada (SPARCC) has similar recommendations for AS treatmentCitation13.

Secukinumab is the first fully human monoclonal antibody that selectively neutralizes interleukin (IL)-17A. Health Canada approved secukinumab in April 2016 for the treatment of adult patients with active AS who have responded inadequately to conventional therapyCitation14. Secukinumab is a highly efficacious treatment for AS, demonstrating a rapid onset of action, sustained clinical response, and a good safety profile according to the results of several phase 3 clinical trialsCitation15–18. Secukinumab showed higher improvement in signs & symptoms vs adalimumab in matching-adjusted indirect comparison (MAIC)Citation19. A head-to-head superiority study (SURPASS) vs adalimumab with radiographic progression as the primary endpoint is underwayCitation20.

We report the results of a cost-effectiveness study of secukinumab 150 mg in comparison with the currently licensed biologics (certolizumab pegol, adalimumab, golimumab, etanercept and etanercept biosimilar, infliximab and infliximab biosimilar) over 60 years of time horizon (lifetime) among the biologic-naïve population. The perspective is that of the Canadian healthcare system. This is the first cost-effectiveness analysis on secukinumab for AS in Canada.

Methods

Patient population and interventions

The target population is Canadian adults aged 18 years of age and older who fulfilled the modified New York criteria for AS and exhibited inadequate response to NSAIDs. The base case analysis was conducted in a biologic-naïve population (having no prior exposure to biologics). The population inputs shown in Supplementary Table SCitation1 define the baseline characteristics for the selected model population. Population data are calculated as the weighted average across all patients from the MEASURE 1 and MEASURE 2 pooled trial dataCitation21.

Details regarding treatment regimens like dosing and frequencies are available in Supplementary Table SCitation2. Biosimilars for etanercept and infliximab are included in the model with the assumption of equivalent efficacy to the originator and different drug acquisition costs.

Model structure

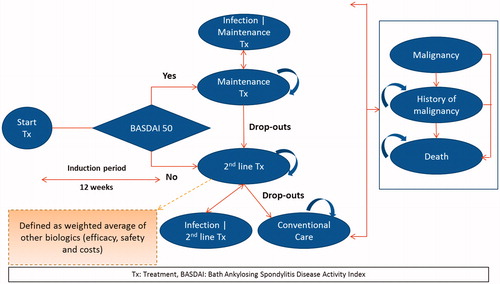

A semi-Markov model was developed using Microsoft Excel, and the model structure can be seen in . This structure was chosen based on time-dependent probabilities associated with mortality. Patients start a given treatment, and the response to treatment was assessed using a 50% improvement of the initial Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI 50) response at 3 months.

In the model, patients transitioned to different health states dependent on the probabilities of BASDAI 50 response rate, drop-out rate, serious infection, malignancy, and death. Malignancy and adverse events (AEs) such as infections were modeled as separate health states to better track their associated costs and quality-of-life effects. Patients that experienced infections were allowed to continue biologic treatment or switch to conventional care (CC). It was assumed that all patients discontinued biologic treatment upon entering the “Malignancy” health state. Patients in the malignancy health state had a higher risk of mortality for an additional 2 years following initial malignancy event. Upon entering the malignancy health state, patients could move to death or stay in the health state to track the history of malignancy and to model time-dependent survival probabilities following malignancy.

Patients switched to a subsequent-line biologic treatment upon discontinuing the initial line of treatment. In the absence of relevant data for subsequent-line biologics, average values of the efficacy, costs, and AE incidence rates across all biologics were considered. No switching to biologics was allowed for patients receiving CC.

Model inputs

Clinical inputs

The main clinical input for the model was BASDAI 50 response at 3 months (Supplementary Table SCitation3), which is consistent with the existing British Society for Rheumatology treatment recommendationCitation22, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) appraisals for ASCitation23,Citation24, and the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) drug expert committee recommendationCitation25. BASDAI consists of a 1–10 scale, which is based on five major symptoms of AS including fatigue, spinal pain, joint pain/swelling, enthesitis, morning stiffness duration, and morning stiffness severityCitation26. BASDAI 50 response refers to patients having a 50% improvement in BASDAI score from baseline. This is used to classify patients as responders and non-responders. Additional clinical inputs include short-term changes in the BASDAI and Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) responses (Supplementary Table SCitation4), which measures change in BASDAI and BASFI scores at 3 months from baseline; long-term changes in BASFI response captured at 1 year through the modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spinal Score (mSASSS) (Supplementary Table SCitation5), and biologic withdrawal rates (Supplementary Table SCitation6). Long term BASFI change over time is modeled to characterize the progression of AS, specifically to model the impact of different clinical processes on BASFI over time. Specifically, the independent effects on BASFI because of disease activity (BASDAI) and the extent and progression of radiographic disease (as measured by the mSASSS) for AS is measured. It allows for consideration of the impact on BASFI that might be achieved via symptomatic improvements (i.e. in terms of reductions in disease activity) and those which might be conferred by disease modification properties (i.e. the effect on the likelihood and/or rate of further radiographic progression).

The comparative effectiveness data for treatments including change in BASDAI and BASFI at 3 months were taken from a Bayesian network meta-analysis (NMA)Citation27. NMAs were conducted in accordance with health technology assessment guidanceCitation28. A total of seven trials were identified for biologic-naïve patients involving 1,361 patients. Randomized clinical trial data for the respective drugs were used to inform the NMA27. Wherever the data were missing for any biologic, an average of other biologics was taken.

Cost inputs

Four types of direct costs were incorporated into the model including drug acquisition costs, disease-related costs, medical support costs, and AE costs. The drug acquisition costs for secukinumab and comparators were obtained from the Ontario drug benefit formulary/comparative drug index ()Citation29.

Table 1. Drug acquisition costs for biologics for AS patients in Canada.

Disease-related costs included to account for the AS disease management costs are estimated based on an exponential BASFI regression model, where Cost (CAD) = CAD 2,421.51 × EXP (0.213 × BASFI)Citation30,Citation31.

Medical support costs included costs related to medical visits, as well as laboratory test (Supplementary Table SCitation7).

The model also included costs for treating and managing adverse events. The adverse events considered in the model are serious infection and malignancy as the product labels include caution for these events (Supplementary Table SCitation8).

All costs were converted to CAD, if they were not already available in CAD. All cost inputs were inflated to 2018 using the general Canadian Consumer Price IndexCitation32. A sole Canadian healthcare system perspective was considered in this analysis. Hence, all indirect costs, such as productivity losses, were excluded.

Utility inputs

Utility weight inputs were used in the model to calculate quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) to reflect the improvement in health-related quality-of-life experienced by patients who achieved the various levels of BASDAI and BASFI responses. A linear mixed model was used to fit the EQ-5D utility score as a response variable and BASDAI and BASFI response scores, age and sex as predictors (Supplementary Table SCitation9). The model also included disutilities associated with AEs of serious infection and malignancy (Supplementary Table SCitation10).

Mortality inputs

Three mortality inputs were considered in the analysis: age-related all-cause mortality, disease-specific mortality, and AE-related mortality. Higher mortality rates associated with older age were incorporated in the form of all-cause mortality. All-cause mortality was estimated based on the National Life Tables for Canada and are presented in Supplementary Table S1133. AS patients have a higher mortality rate compared to the general population. The disease-specific mortality risk was based on relative risk values to account for higher mortality in AS patients vs the general population (Supplementary Table SCitation12). In addition, relative risks of mortality due to AEs, such as tuberculosis, other serious infection, or malignancy were obtained from the literature (Supplementary Table SCitation12).

Base case analyses

The analyses assessed the cost-effectiveness of subcutaneous secukinumab 150 mg in a biologic-naïve population compared to other licensed biologics (subcutaneous treatments with certolizumab pegol, adalimumab, golimumab, etanercept and its biosimilar, and intravenous treatments with infliximab and its biosimilar). The primary effectiveness outcome was QALYs.

The primary analysis was conducted over a lifetime horizon due to the chronic nature of the disease (60 years of disease duration considered for the present analysis). Future costs and outcomes were discounted with a discounting rate of 1.5% per annum for all treatmentsCitation34.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses (deterministic one-way, probabilistic, and alternative scenario analyses) were carried out to assess the robustness of the findings.

In deterministic one-way sensitivity analysis, the model input parameters such as BASDAI 50 response rate, disease-related costs, laboratory costs, AE costs, and utility weight inputs were modified (one at a time) by ±10% to identify sensitive parameters with the largest effect on model results (see lower and upper bound assumptions in Supplementary Table SCitation13).

In probabilistic sensitivity analysis, to estimate the uncertainty around the results, the model was run 1,000 times assuming a certain distribution for each input in the model and a specific cost and QALY was generated for each comparator. These were plotted as a scatter plot and, furthermore, results were presented using cost-effectiveness acceptability curves for each treatment calculated from the net monetary benefit statistic across a wide range of willingness-to-pay thresholds. The net monetary benefit statistic was selected because it allowed for the comparison of all treatment regimens simultaneously (distributions are shown in Supplementary Table SCitation13).

Various alternative scenario analyses were also carried out in the model. This included analyses for a mixed population (a combination of biologic-naïve and biologic-experienced populations), using other published utility valuesCitation35, excluding disutilities, and assuming an initial gain on BASFI rebound assumption (see for alternative assumptions).

Table 2. Summary of ICER results for secukinumab vs biologics by varying base-case assumptions.

Results

Base case results

Secukinumab 150 mg was compared with the other biologics to assess its cost-effectiveness in the biologic-naive population. In this population, patients treated with secukinumab 150 mg achieved the highest number of 16.46 QALYs at a total cost of CAD 533,010. Golimumab achieved the second highest number of 16.13 QALYs at a total cost of CAD 588,053, followed by certolizumab pegol, which achieved 15.78 QALYs at a total cost of CAD 586,732. The total costs and QALYs for all comparators are reported in . As secukinumab had the highest number of QALYs at the lowest cost among all treatments, it dominated all comparators in this population.

Table 3. Total costs, QALYs for biologic-naïve AS patients over a lifetime horizon (60 years).

Among all biologics, secukinumab had lower overall drug and other medical costs (consisting of disease related costs, monitoring, and adverse events related costs), leading to lower total costs (). Lower costs were seen due to lower dropouts beyond year 1 among those on secukinumab (withdrawal rates of 1.6% among those on secukinumab vs 6.2–25.1% among those on comparators beyond year 1) (Supplementary Table SCitation6), which led to less patients on a more expensive subsequent line of treatment. Lower dropouts meant more patients tended to stay in the maintenance treatment phase leading to a higher BASFI score, thus contributing to higher QALYs. In addition, a lower incidence of adverse events like serious infections among patients on secukinumab (low serious infection rates of only 0.16%) (Supplementary Table SCitation8) also ensured lower costs.

Table 4. Costs and QALYs breakdown.

Sensitivity analysis

In the deterministic one-way sensitivity analysis, model results were most sensitive to BASDAI 50 response at 3 months, baseline BASFI non-responders, and discount rates (Supplementary Figure S1).

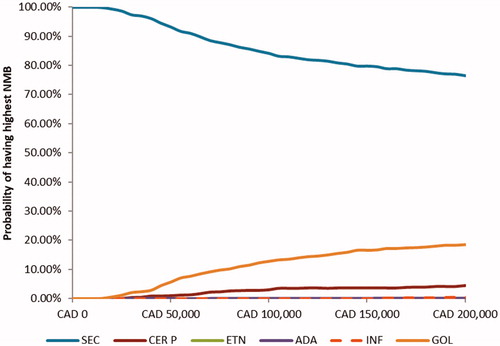

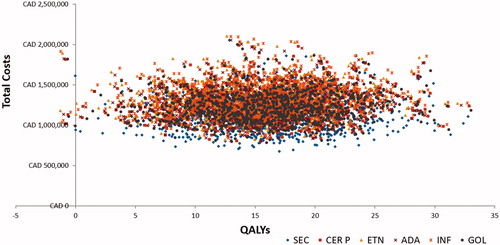

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses demonstrated that, at different willingness-to-pay (WTP) thresholds, the probability of being cost-effective was highest for secukinumab 150 mg in the biologic-naïve population among comparators (). It was observed that, in nearly 89.4% of simulations, secukinumab exhibited lower costs and higher QALYs compared to other biologics. The scatter plot representing costs and QALYs for all treatment is available in .

Figure 2. Probability of net monetary benefit of AS treatments at different willingness-to-pay thresholds. NMB, Net monetary benefit; SEC, secukinumab; ADA, adalimumab; CER P, certolizumab pegol; ETN, etanercept; GOL, golimumab; INF, infliximab.

Figure 3. Cost-effectiveness scatter plot. ADA, adalimumab; CAD, Canadian dollar; CE, cost-effectiveness; CER P, certolizumab pegol; ETN, etanercept; GOL, golimumab; INF, infliximab; SEC, secukinumab; QALYs, quality adjusted life years.

For the alternate scenario analyses, considering the mixed population (combination of biologic-naïve and biologic-experienced) perspective, results were similar to base-case analysis, with secukinumab 150 mg (14.98 QALYs at a total cost of CAD 1,141,452) dominating all other biologics (golimumab achieved the highest number of 14.74 QALYs at a total cost of CAD 1,230,255). Secukinumab 150 mg also dominated all comparators in all other alternative scenarios, reinforcing the robustness of our analysis. A summary of results for all alternate scenarios is presented in .

Discussion

The present analysis assessed the cost-effectiveness of secukinumab 150 mg vs currently licensed biologics (certolizumab pegol, adalimumab, golimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept and etanercept biosimilar, golimumab, infliximab and infliximab biosimilar) for the treatment of AS patients over a lifetime (60 years) in a Canadian healthcare system setting.

Secukinumab 150 mg achieved 16.46 QALYs at a cost of CAD 533,010 over a lifetime horizon in the biologic naïve population. Secukinumab 150 mg produced more QALYs at a lower cost relative to all other comparators. Thus, secukinumab 150mg dominated all comparators. The present model has been submitted and reviewed by NICE and resulted in a positive decision for secukinumab 150 mg in AS36. Different sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of the results.

Several studies from different countries have reported the cost-effectiveness of secukinumab vs other biologics for the treatment of AS (Supplementary Table SCitation14). These include studies from TurkeyCitation37, ColombiaCitation38, the UKCitation39,Citation40, BulgariaCitation41, and RussiaCitation42. As these published studies were conducted for different countries, results are not directly comparable to our study. However, all these published studies also reported that secukinumab is a cost-effective treatment for AS.

The present analysis provides a new body of evidence, particularly as it assesses the cost-effectiveness of a treatment with a novel mechanism of action (IL-17A inhibition with secukinumab) vs the previous treatment standard (TNF inhibition). The model results suggest that, for physicians, payers, and patients, secukinumab should be the first biologic of choice, as more patients can be treated effectively and cost-efficiently.

Various factors add to the strength of this analysis. In the absence of head-to-head trials, the data for comparative efficacy of other biologics was obtained from a NMA which was conducted using Bayesian NMA techniques, which is scientifically robustCitation27. Inclusion of granular cost details (costs for drug acquisition, medical support, adverse events, as well as disease-related costs) provides a real-world picture of the economic burden on a healthcare system due to AS patients. Uncertainty analysis has been done using probabilistic and deterministic sensitivity analysis, as well as alternative scenario analyses, which strengthens the robustness of the results. Considering the chronic nature of diseases like AS, the base case analysis used a lifetime time horizon (60 years).

While the model reflects the merits of the approach used, the model also presents certain limitations. There might be an under-estimation of long-term efficacy of secukinumab, since the effectiveness data is derived from the NMA, which included data up to week 1627. Secukinumab has shown sustained efficacy in signs, symptoms, physical function, and preventing radiographic damage in AS patients up to 4 years in long-term clinical trial dataCitation43,Citation44, and has also demonstrated higher improvement in signs and symptoms vs adalimumab in Matching Adjusted Indirect Comparisons (MAIC)Citation45. Other limitations of this analysis include lack of efficacy data from TNFi in the biologic-experienced population. In the case of missing data, it was assumed that patients are treated with an average biologic based on all other biologics modeled. The societal impact of AS is mainly related to indirect costs. However, these costs, along with costs borne by patients and their families, were not included in the analysis.

Conclusion

Secukinumab dominated (higher QALYs at lower total costs) all modeled biologic treatments (certolizumab pegol, adalimumab, golimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept and its biosimilar, golimumab, infliximab and its biosimilar) in the biologic-naïve population of patients with active AS from the Canadian healthcare system perspective. Treatment with secukinumab translates into substantial benefits for AS patients as well as the Canadian healthcare system.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material contains detailed information on population inputs, biologic drug dosing, clinical inputs, other model inputs and sensitivity analyses inputs and outputs.

Transparency

Declaration of financial/other interests

RG is a consultant for Novartis. SCR is an employee of Novartis Pharmaceuticals Canada Inc., Dorval, Canada. PG and MJ are employees of Novartis Product Life Cycle Services-NBS, Novartis Healthcare Private Limited, Hyderabad, India. SMJ is an employee and shareholder of Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Previous presentation

An abstract titled “Cost-effectiveness analysis of secukinumab in ankylosing spondylitis: a Canadian perspective” was accepted and presented as a poster at the ISPOR 20th Annual European Congress 201746.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (111.4 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank GS Ramakrishna, Novartis Healthcare Private Limited, Hyderabad, India for editorial writing support and RTI Health Solutions for project management support during the model development phase.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Schett G, Lories RJ, D’Agostino MA, et al. Enthesitis: from pathophysiology to treatment. Nature Rev Rheumatol 2017;13:731–41

- Taurog JD. The spondyloarthritides. In: Fauci ASLC, editor. Harrison’s rheumatology. 16th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005. p 139–55

- Garg N, van den Bosch F, Deodhar A. The concept of spondyloarthritis: where are we now? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2014;28:663–72

- Stolwijk C, van Tubergen A, Castillo-Ortiz JD, et al. Prevalence of extra-articular manifestations in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:65–73

- Heuft-Dorenbosch L, Vosse D, Landewe R, et al. Measurement of spinal mobility in ankylosing spondylitis: comparison of occiput-to-wall and tragus-to-wall distance. J Rheumatol 2004;31:1779–84

- Sieper J, Poddubnyy D. Axial spondyloarthritis. Lancet 2017;390:73–84

- Akkoc N. Are spondyloarthropathies as common as rheumatoid arthritis worldwide? A review. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2008;10:371–8

- Dean LE, Jones GT, MacDonald AG, et al. Global prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology 2014;53:650–7

- Barnabe C, Jones CA, Bernatsky S, et al. Inflammatory arthritis prevalence and health services use in the first nations and non-first nations populations of Alberta, Canada. Arthritis Care Res 2017;69:467–74

- Boonen A, van der Linden SM. The burden of ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol Suppl 2006;78:4–11

- Kobelt G, Andlin-Sobocki P, Maksymowych WP. Costs and quality of life of patients with ankylosing spondylitis in Canada. J Rheumatol 2006;33:289–95

- van der Heijde D, Ramiro S, Landewe R, et al. 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:978–91

- Rohekar S, Chan J, Tse SM, et al. 2014 Update of the Canadian Rheumatology Association/Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada treatment recommendations for the management of spondyloarthritis. Part II: specific management recommendations. J Rheumatol 2015;42:665–81

- Novartis Pharmaceuticals Canada Inc. Cosentyx® Product Monograph. Canada: Novartis; 2016. Available at: http://www.novartis.ca [Last accessed July 2017]

- Baeten D, Sieper J, Braun J, et al. Secukinumab, an interleukin-17A inhibitor, in ankylosing spondylitis. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2534–48

- Sieper J, Deodhar A, Marzo-Ortega H, et al. Secukinumab efficacy in anti-TNF-naive and anti-TNF-experienced subjects with active ankylosing spondylitis: results from the MEASURE 2 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:571–92

- Pavelka K, Kivitz A, Dokoupilova E, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of secukinumab in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized, double-blind phase 3 study, MEASURE 3. Arthritis Res Ther 2017;19:285

- Kivitz AJ, Wagner U, Dokoupilova E, et al. Efficacy and safety of secukinumab 150 mg with and without loading regimen in ankylosing spondylitis: 104-week results from MEASURE 4 study. Rheumatol Ther 2018 Aug 18. doi:10.1007/s40744-018-0123-5. PubMed PMID: 30121827; eng

- Maksymowych WP, Strand V, Baeten D, et al., editors. Secukinumab for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: comparative effectiveness results versus adalimumab for up to 52 weeks using a matching-adjusted indirect comparison (P147). 10th International Congress on Spondyloarthritides. September 15–17, 2016, Ghent, Belgium

- Clinicaltrials.gov. Effect of secukinumab on radiographic progression in ankylosing spondylitis as compared to GP2017 (adalimumab biosimilar). 2017. Available at: https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03259074 [Last accessed January 2018]

- Braun J, Baraliakos X, Kiltz U. Secukinumab (AIN457) in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2016;16:711–22

- Keat A, Barkham N, Bhalla A, et al. BSR guidelines for prescribing TNF-alpha blockers in adults with ankylosing spondylitis. Report of a working party of the British Society for Rheumatology. Rheumatology 2005;44:939–47

- NICE. TNF-alpha inhibitors for ankylosing spondylitis and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: NICE Technology Appraisal 383. UK: NICE; 2016. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/TA383 [Last accessed July 2017]

- NICE. Golimumab for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. NICE Technology Appraisal 233. UK: NICE; 2011. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta233 [Last accessed July 2017]

- CADTH. Canada expert drug advisory committee final recommendation and reconsideration and reasons for recommendation. Canada: CADTH; 2007 Available at: https://www.cadth.ca/sites/default/files/cdr/complete/cdr_complete_Humira_Resubmission_June-27-2007.pdf2007 [Last accessed October 4, 2018]

- Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, et al. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J Rheumatol 1994;21:2286–91

- Baeten DPM, Strand V, McInnes I, et al. Secukinumab for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: comparative effectiveness results versus currently licensed biologics from a network meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75(suppl 2):809–810

- Dias S, Welton NJ, Sutton AJ, et al. NICE decision support unit technical support documents. A generalised linear modelling framework for pairwise and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2014

- Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Ontario drug benefit formulary/comparative drug index. Ottawa, Ontario: Government of Canada; 2016. Available at: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/drugs/odbf/odbf_except_access.aspx2016 [Last accessed May 5, 2016]

- Corbett MSM, Jhunti G, Rice S, et al. TNF-alpha inhibitors for ankylosing spondylitis and axial spondyloarthritis without radiographic evidence of ankylosing spondylitis (including a review of technology appraisal 143 and technology appraisal 233). York: CRD/CHE Technology Assessment Group (Centre for Review and Dissemination/Centre for Health Economics) University of York; 2014

- Corbett M, Soares M, Jhuti G, et al. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors for ankylosing spondylitis and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2016;20:1–334, v–vi

- Statistics Canada. Consumer Price Index, historical summary (1996 to 2017) [Internet]. Government of Canada; Ottawa, Ontario; 2018. Available at: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/econ46a-eng.htm [Last accessed August 19, 2016]

- Statistics Canada. Probability of dying by age and sex, Canada, 2007/2009 period. Ottawa, Ontario: Government of Canada; 2013. Available at: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/91-209-x/2013001/article/11785/c-g/desc/desc02-eng.htm [Last accessed August19, 2016]

- CADTH Guidelines for the Economic Evaluation of Health Technologies: Canada; 2017. Available at: https://www.cadth.ca/sites/default/files/pdf/economic_guidelines_worked_example.pdf 2017 [Last accessed October 4, 2018]

- McLeod C, Bagust A, Boland A, et al. Adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and economic evaluation [Review]. Health Technol Assess 2007;11:1–158, iii–iv

- NICE. NICE Technology Appraisal - Secukinumab for active ankylosing spondylitis after treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or TNF-alpha inhibitors [TA 407]. UK: NICE; 2016. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta407 [Last accessed April 1, 2018]

- Sarioz F, Ozdemir O, Direk S, et al. Secukinumab is dominant vs. TNF-inhibitors in the treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis: results from a Turkish cost-effectiveness model. Value Health 2017;20:A534

- Romero Prada ME, Roa Cardenas NC, Serrano GY, et al. Cost-utility analysis of secukinumab use versus tnf-a inhibitors, in patients with ankylosing spondilytis. Value Health 2017;20:A938–A939

- Marzo-Ortega H, Halliday A, Jugl S, et al. The cost-effectiveness of secukinumab versus tumour necrosis factor a inhibitor biosimilars for ankylosing spondylitis in the UK. Rheumatology 2017;56:ii92

- Emery P, Van Keep M, Beard SM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of secukinumab for the treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis in the UK. Value Health 2017;20:A534

- Djambazov S, Vekov T. Incremental cost-effectiveness analysis of biological drug therapies for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis in Bulgaria, 2016. Value Health 2017;20:A221

- Fedyaev D, Derkach EV. Cost-effectiveness analysis of different biologic agents for ankylosing spondylitis treatment in Russia. Value Health 2016;19:A539

- Braun JBX, Deodhar AA, Poddubnyy D, et al. Secukinumab demonstrates low radiographic progression and sustained efficacy through 4 years in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69

- Baraliakos X, Braun J, Deodhar A, et al. SAT0268 secukinumab demonstrates low radiographic progression and sustained efficacy through 4 years in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77(Suppl 2):997–8

- Maksymowych W, Strand V, Baeten D, et al. OP0114 secukinumab for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: comparative effectiveness results versus adalimumab using a matching-adjusted indirect comparison. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75(Suppl 2):98

- Chiva-Razavi S, Jain M, Graham CN, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of secukinumab in ankylosing spondylitis: a Canadian perspective. Value Health 2017;20:A533–A534