Abstract

Aims: This retrospective chart review examined the six-month migraine-related healthcare resource use (HRU) among European patients who had ≥4 migraine days per month and previously failed at least two prophylactic migraine treatments.

Methods: Neurologists, headache specialists, and pain specialists in France, Germany, Italy, and Spain who treated ≥10 patients with migraine in 2017 were recruited (April–June 2018) to extract anonymized patient-level data. Eligible physicians randomly selected charts of up to five adult patients with clinically-confirmed migraine, ≥4 migraine days in the month prior to the index date, and had previously failed at least two prophylactic migraine treatments. Treatment failure was defined as discontinuation due to lack of efficacy and/or tolerability. Demographic and disease characteristics as of the index date, and migraine-related HRU incurred during the 6-month study period, were recorded.

Results: A total of 104 physicians contributed 168 charts for patients (63% female). On average, patients were 38 years old and failed 2.3 prophylactic treatments as of the index date. During the study period, 83% of patients had ≥1 outpatient visit for migraine in the physician’s office, and 27% went to the ER/A&E. Approximately 5% of patients were hospitalized for migraine, with an average of one hospitalization and an average length of stay of 3 days. Approximately 39% of patients had ≥1 blood test, 22% had ≥1 magnetic resonance imaging, 17% had ≥1 electroencephalogram, and 13% had ≥1 computerized tomography scan. Visits to other healthcare providers were common.

Limitations: This study is subject to the limitations of chart review studies, such as errors in data entry.

Conclusions: Across four European countries, the HRU burden of migraine among patients who previously failed at least two prophylactic treatments was high, indicating a need for more effective prophylactic treatments to appropriately manage migraine and reduce the HRU burden attributable to this common disorder.

Introduction

Migraine is a common neurological disorder typically characterized by recurrent severe headaches and often accompanied by sensory and autonomic symptoms such as nausea and/or light and sound sensitivityCitation1,Citation2. Migraine has been ranked among the top causes of disability globally and affects multiple domains of life for individuals (i.e. health, personal, career, etc.)Citation3. While the condition affects both sexes, it is more prevalent among women than menCitation4,Citation5. Comorbidities common among people with migraine include stroke, coronary heart disease, depression and anxiety, epilepsy, and fibromyalgia, among othersCitation6,Citation7. Approximately 11–16% of the worldwide population experiences migraineCitation8,Citation9, although estimates of prevalence vary depending on the definition of migraine (i.e. chronic vs episodic, or whether clinical criteria such as those outlined in the International Classification of Headache Disorders [ICHD-2] are applied). A literature review by Stovner and AndreeCitation10 estimated that the prevalence of migraine in Europe was ∼15%. Due to the high prevalence and substantial impact migraine has on patients and health systemsCitation11,Citation12, the cost of migraine in Europe was estimated at €27 billion annually in 2008Citation13.

The management of migraine depends on the type of headache and can include the modification of identified triggers, prescription of pharmaceuticals for acute symptom relief, and/or prophylaxis to reduce the frequency and severity of future episodes. Depending on the country, common prophylactic migraine treatments may include flunarizine, propranolol, metoprolol, timolol, amitriptyline, divalproex, sodium valproate, onabotulinumtoxinA, and topiramateCitation14,Citation15. While there are no universally accepted guidelines for the initiation of migraine prophylaxis, appropriate candidates include patients with >3 migraine days per month, contraindications to acute medications, and/or headache-related impairmentCitation16. Epidemiologic studies have suggested that ∼38% of patients with migraine need preventive treatment, but only 3–13% currently use itCitation17.

However, even among patients who receive migraine prophylaxis, treatment adherence is often suboptimal and patients have high rates of discontinuation and treatment switching for reasons including adverse events, patient choice, and loss to follow-upCitation18–20. Berger et al.Citation19 reported that, by the end of a 6-month follow up period, 67–73% of patients who initiated migraine prophylaxis with antidepressants, antiepileptics, or beta blockers were non-adherent. Hepp et al.Citation18 reported that among patients with chronic migraine using oral prophylactic migraine medication, over two-thirds had discontinued by 6 months, the majority of whom remained untreated for an extended period before switching to a new treatment. Thus, patients who have discontinued multiple prophylactic treatments may go untreated for periods of time and impose a high burden on the health system.

Few studies have examined the burden of migraine treatment failure on healthcare resource utilization (HRU). Bloudek et al.Citation21 estimated the healthcare burden associated with migraine in Europe using a survey of migraine patients in five countries. That study found that the most common services used for migraine were healthcare provider visits, diagnostic testing, and blood tests, and that these resources were used far more frequently by patients with chronic vs episodic migraine. However, the authors did not assess resource use by prophylactic treatment history or treatment failure, and, to date, the healthcare burden of prophylactic treatment failure has not been quantified.

To address this gap in the literature, this study aimed to estimate the 6-month migraine-related HRU among patients in France, Germany, Italy, and Spain who had four or more migraine days per month and who previously discontinued at least two prophylactic migraine treatments due to lack of efficacy and/or tolerability.

Methods

Data source

This retrospective, non-interventional, panel-based chart review study collected anonymized patient-level clinical and HRU data extracted by neurologists, headache specialists, and pain specialists from France, Germany, Italy, and Spain (four of the five most populous European nations in the European Union). Physicians were recruited by a leading global market research provider with a large and well-established panel of neurologists and headache specialists. The physicians were from geographically diverse sites and practiced at academic, community, and private practices. Practicing physicians were screened from April 2018 to June 2018 for treating ≥10 patients with migraine in 2017, and those eligible were invited to randomly select up to five patient charts that met the pre-specified inclusion criteria described below. De-identified data were collected through an electronic case report form developed by the study investigators that had been pilot-tested by one physician from each country. Each chart extraction took ∼15–20 minutes for the contributing physicians to complete. This study was granted an exemption from full institutional board review by the Western Institutional Review Board on March 14, 2018.

Study population and selection criteria

Physicians followed a random patient selection process in which a random letter was generated by the survey and physicians were instructed to pull all charts for patients with a last name starting with that letter. Physicians were then told to identify the first of these charts that met all of the eligibility criteria described below. The potential for “recall bias” was minimized using logic checks and allowing the answer choices of “unknown/not sure”.

Charts of patients who initiated at least one prophylactic treatment for migraine and included migraine-related medical records available from the first time the patient saw the physician for migraine through their last follow-up for migraine were eligible for this study. In addition, physicians were required to know the total number of prophylactic migraine treatments the patient received, including treatments prescribed before the patient was first under the physician’s care. The most recent date of a prescription for a prophylactic treatment for migraine on or after January 1, 2013 that met all of the following criteria was defined as the index date: (1) patient was ≥18 years old; (2) patient had a history of migraine, including evidence of International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD)-1st, 2nd, or 3rd edition criteriaCitation22–24, or physician notes specifying migraine in the patient chart; (3) patient had 4 or more migraine days in the month prior to the date; (4) patient previously discontinued at least two prophylactic migraine treatments due to lack of efficacy and/or tolerability; and (5) patient was under the care of the physician for ≥6 months after the date. There was no requirement that the patient must have visited the physician during the 6-month period following the index date. The patient may have initiated prophylactic treatment in a different setting while still under the physician’s care.

Chart extraction

The online chart extraction form included three sections used to identify and confirm physician and patient eligibility. The first section contained questions related to the physician’s experience and practice to determine the eligibility of the physician. The second section showed the list of patient inclusion/exclusion criteria and required acknowledgement by the physician that selected patients met these eligibility criteria. The third section contained questions that were answered based on information contained in the patient’s medical chart to confirm the eligibility of the patient. The online chart extraction form was tested following potential modifications from the pilot test (one physician from each country) and soft launch (10% of physicians) to ensure that all questions were clear and correctly interpreted. During the pilot test, physicians could comment on the online chart extraction form and validate questions.

Data entered in the chart extraction forms were reviewed to assure quality (i.e. checking for extremely short completion times, typos in entry, misinterpretation, etc.) and consistency, and data range checks were performed (e.g. ensuring that the age of patients met eligibility criteria and that the dates entered for key events were chronologically accurate).

Study definitions

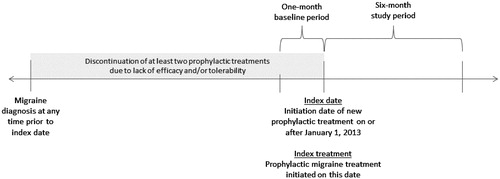

The study’s design is shown in . The baseline period was defined as the 1-month period prior to the index date. The study period was defined as the 6-month period following the index date. The index treatment was the prophylactic migraine treatment initiated on the index date. Treatment failure was defined as discontinuation due to lack of efficacy and/or tolerability.

Study measures

The following patient and disease characteristics were collected during the baseline period: demographics (age, sex, weight, body mass index [BMI]) at the index date, employment status, comorbidities prior to the index date, loss of productivity due to migraine (yes/no), days of work/school missed due to migraine, time since initiation of prophylactic treatment, the average number of migraine days and non-migraine headache days per month and the average duration in hours of a migraine episode and of a non-migraine headache.

Migraine-related HRU outcomes assessed during the study period included the numbers of migraine-related prescribed sick days, migraine-related outpatient visits, migraine-related emergency room (ER)/accident and emergency (A&E) visits, migraine-related hospitalizations and days hospitalized, diagnostic migraine-related procedures (i.e. cranial computerized topography [CT] scans, electroencephalograms [EEGs], cranial and cranio-cervical magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] scans, and blood tests), interventional migraine-related procedures (transcutaneous nerve stimulator procedures and occipital nerve block procedures), and migraine-related nurse practitioner, psychologist, psychiatrist, physiotherapy, or other specialist visits.

Statistical analyses

The analyses were conducted among all eligible patients from the four countries who failed at least two prophylactic treatments for migraine prior to initiating the index treatment. Categorical variables were summarized using counts and percentages, and continuous variables were summarized using means and standard deviations (SD). Only observed data were used, and missing variables were not imputed. Physicians were required to input HRU at their practice completely. For key questions, such as number of migraine-related hospitalizations and ER/A&E visits that would occur outside the practice, only 2% and 4% of the data were missing entries, respectively. Sub-group analyses stratified by country were also conducted.

Results

Physician characteristics

A total of 104 physicians from France (n = 28), Germany (n = 17), Italy (n = 38), and Spain (n = 21) contributed charts for patients who failed at least two prophylactic treatments for migraine ( and Supplementary Appendix ). These physicians treated an average of 298 patients with migraine in 2017 and had an average of 15 years in practice. The majority of physicians (55%) practiced in an academic, teaching, or tertiary hospital, and 72% worked in small practices with 1–5 neurologists/headache specialists. In addition to neurologists (75%) and headache specialists (37%), 10% of the physicians identified themselves as pain specialists.

Table 1. Physician characteristics.

Patient characteristics

The physicians contributed 168 patients from France (n = 51), Germany (n = 28), Italy (n = 44), and Spain (n = 45) who had failed at least two prior prophylactic treatments for migraine ( and Supplementary Appendix ). The mean age of the patients was ∼38 years at the index date, and a numerically higher proportion were female (63%). The majority of patients were employed full time (57%). The average BMI was ∼24 and ∼41% of patients had no comorbidities prior to the index date, whereas 26% had anxiety, 23% had depression, 15% had hypertension, and 10% had obesity.

Table 2. Characteristics of patients with two or more failed prophylactics for migraine.

Disease characteristics

On average, initiation of the index treatment was 3.5 years after the initiation of the first prophylactic treatment for migraine ( and Supplementary Appendix ). In the month prior to the index date, patients experienced an average of ∼10 migraine days, with an average migraine duration of 22 h per migraine episode. Patients missed an average of 5 days of work/school due to migraine, and 81% suffered from a loss of productivity at work/school due to migraine in the month before the index date.

Table 3. Disease characteristics of patients with two or more failed prophylactics for migraine.

Migraine-related HRU

During the 6-month study period, ∼83% of the patients had at least one outpatient visit for migraine in the physician’s office and 27% went to the ER/A&E (). These patients had an average of three outpatient visits and three ER/A&E visits due to migraine during that time period. A total of 17% of patients did not have an outpatient visit. Approximately 5% of patients were hospitalized for migraine, with an average of one hospitalization and an average length of stay (LOS) of 3 days. Nearly one-third (32%) of patients were prescribed sick days by participating physicians, with an average of 8 sick days. Diagnostic migraine-related procedures were common during the study period, and ∼39% of patients had at least one blood test, 22% had at least one MRI, 17% had at least one EEG, and 13% had at least one CT scan. Interventional migraine-related procedures were less common, with ∼8% of patients receiving nerve stimulation and 7% receiving a transcutaneous occipital nerve block. Visits to other healthcare providers were common, with 18% of patients receiving care from a psychologist, 13% from a psychiatrist, 19% from a physiotherapist, and 8% from another specialist.

Table 4. Migraine-related HRU during the 6-month study period by patients with two or more failed prophylactics for migraine.

In the stratified analysis by country (Supplementary Appendix ), Spain had the numerically highest proportion of patients with at least one migraine-related ER/A&E visit (34% and an average of three visits among those who had at least one visit), followed by France (32% and an average of two visits), Italy (23% and an average of five visits), and Germany (13% and an average of two visits). Germany had the numerically highest proportion of patients with at least one migraine-related hospitalization (23% and an average LOS of 3 days), followed by France (6% and an average LOS of 3 days); no patients in Italy or Spain had migraine-related hospitalizations. Germany also had the numerically highest proportion of patients with at least one outpatient visit (100% and an average of three visits), followed by Spain (91% and an average of two visits), Italy, (86% and an average of three visits), and France (65% and an average of two visits).

Discussion

This chart review study of European patients with four or more migraine days in the month prior to the index date found that HRU was high during the 6-month study period despite the recent initiation of a prophylactic treatment for migraine. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate HRU among patients with prophylactic treatment failures and sheds light on the burden of sub-optimal prophylactic treatment, which is often discontinued due to lack of efficacy and/or tolerabilityCitation18,Citation19.

Few prior studies have assessed the HRU burden of migraine in Europe, and none have specifically focused on patients who have failed prophylactic treatment for migraine. Bloudek et al.Citation21 estimated the HRU and medical costs associated with chronic (≥15 headache days/month, of which 8 are migraine days) and episodic (<15 headache days/month) migraine among patients in the UK, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain. They reported that patients with chronic migraine had more outpatient, hospital, and ER/A&E visits as well as more diagnostic tests than those with episodic migraine. The patients with chronic migraine in Bloudek et al.Citation21 had a comparable number of ER/A&E visits to the patients in the present study; however, a numerically higher proportion of the patients in the present study were hospitalized due to migraine. Bloudek et al.Citation21 reported that the annual medical costs were generally the highest in the UK and Spain and lower in France and Germany. While the present study did not record costs as Bloudek et al.Citation21, it did find that Spain had the numerically highest proportion of patients with at least one migraine-related ER/A&E visit and had the second highest rate of outpatient visits, although no patients had hospitalizations. Germany had the numerically lowest proportion of patients with at least one migraine-related ER/A&E visit, but the highest rate of hospitalizations and outpatient visits.

In the present study, the majority of patients in all countries had at least one outpatient visit for migraine during the study period, and in Germany, 100% of the patients had at least one outpatient visit. Almost one-third of all patients visited the ER/A&E for migraine for an average of three times, and over 5% of the patients were hospitalized due to migraine and spent an average of 3 days in the hospital. In addition to the high rates of provider visits and hospitalizations, many patients in this study received procedures and blood tests during the study period, and almost one-fifth received care from a physiotherapist or a psychologist. While there was a consistently high burden of migraine-related HRU across the four countries, there was variation in the commonly used types of resource use. For example, Germany had numerically higher rates of migraine-related hospitalizations, while Spain, France, and Italy had numerically higher rates of migraine-related ER/A&E visits. These high rates of migraine-related hospitalizations and ER/A&E visits are both expensive and preventable, suggesting a deficit in the current treatments patients are receiving for migraine prophylaxis.

In this study, about one-third of the patients were prescribed with an average of 8 sick days during the study period. This demonstrates the high societal burden and indirect costs associated with migraine among patients who failed multiple prophylactic treatments. Furthermore, the direct and indirect burden of migraine estimated in this study (sick days, outpatient visits, and migraine-related procedures) is likely to be conservative, as all patients received prophylactic migraine treatment for at least a portion of the study period. Additionally, while the physicians who participated in the study had full data on the HRU incurred in their office, they may have had limited information on the HRU outside of their offices. Because it is possible that patients were seen by multiple physicians for migraine, the HRU burden described is likely an under-estimate as it represents only the portion of the patient’s healthcare known to the contributing physician. Even with this under-estimate, the burden of migraine among patients who had at least two prior prophylactic treatment failures was high, and there is a need for more effective prophylactic treatments in order to appropriately manage migraine and reduce the HRU burden due to migraine. In addition, the current HRU results are likely an under-estimate of the true burden of migraine treatment failure since they were collected after patients initiated a new prophylactic treatment. However, the interaction between treatment type and subsequent HRU was not assessed, and should be explored in future studies. Similarly, the proportion of females in this study is smaller as compared to literature describing the prevalence of migraine overall, as migraine is three-times more prevalent in women vs menCitation25. As there is limited literature describing a population with at least two previous prophylactic treatment failures, examining these differences by sex, this is an especially good area for future research.

Medical charts represent a rich source of existing clinical data, and this retrospective chart review study benefits from several strengths. For example, migraine diagnosis can be clinically confirmed in a chart review, unlike a patient survey where the migraine diagnosis is provided by the patient. Similarly, chart reviews are subject to less recall bias and the data reflect the real-world patterns of care. Data extraction was carefully monitored and the quality of the data was reviewed, and a pilot test was performed with physicians to ensure that the questions were correctly interpreted.

This study is also subject to several limitations, some of which are common to retrospective or chart review studies. For example, there is the possibility for errors introduced during data entry as physicians extract the information. However, logic checks in the questionnaire and in the analysis programs were implemented to minimize the errors, such as ensuring that the initiation of the index prophylactic treatment occurred after the physician first saw the patient. This study may also be affected by inaccurate data recorded in the primary charts, recall bias (e.g. “unknown/not sure” response options), and non-random missing data (e.g. specifically omitting a particular answer option across questions). While the patients eligible for the study were required to have four or more migraine days in the month prior to the index date, there was no requirement for number of migraine days per month during the study period. Thus, the average migraine days per month during this period may have been lower. Like many chart reviews, the sample size of this study is relatively small, thus characteristics or outcomes with low occurrence rates may not be estimated reliably. In addition, this study did not compare the results with a control group without treatment failure, which is a topic that should be explored in the future. However, this study was designed to describe the HRU among a pre-specified patient population, instead of assessing the changes in migraine days per month or efficacy of specific treatments. Despite these limitations, this study provides timely clinical data within a snapshot of patients with migraine in Europe who previously failed two or more prophylactic treatments.

Conclusions

Across all four European countries analyzed, the HRU burden of migraine among patients who failed at least two prior prophylactic treatments was high. The majority of these patients had at least one outpatient visit due to migraine during the 6-month study period, around a third of patients had an ER/A&E visit, and nearly half of patients had some migraine-related procedures or tests. In addition, around a third of patients were prescribed sick days (with an average of eight in the 6-month study period), demonstrating a high personal and societal burden associated with migraine even after the initiation of a new prophylactic treatment. These findings indicate that there is a need for more effective prophylactic treatments to appropriately manage migraine and reduce the HRU burden attributable to this common disorder.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This research was sponsored by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp., and the sponsors were involved in all stages of the work and in the manuscript preparation.

Declaration of financial/other interests

ES, WG, MLZ, EF, and EF are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., which has received consulting fees from Novartis. PV, MAV, TT, NM, MMP, SR, MN, and DR are employees of Novartis. The peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work. In addition, a reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed receiving compensation for consulting services and/or speaking activities from Novartis. Another reviewer of this manuscript has disclosed being involved in clinical studies and advisory boards of various pharmaceutical companies in the headache field, including Novartis. The reviewers have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (48.2 KB)Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance was provided by Shelley Batts, an employee of Analysis Group, Inc. and funded by the sponsor.

References

- Persico AM, Verdecchia M, Pinzone V, et al. Migraine genetics: current findings and future lines of research. Neurogenetics. 2015;16:77–95.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (Beta version). 2013 [cited 2017 February 1]. Available from: https://www.ichd-3.org/.

- Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Vos T, et al. Migraine is first cause of disability in under 50s: will health politicians now take notice? J Headache Pain. 2018;19:17.

- Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68:343–349.

- Hazard E, Munakata J, Bigal ME, et al. The burden of migraine in the United States: current and emerging perspectives on disease management and economic analysis. Value Health. 2009;12:55–64.

- Wang S-J, Fuh J-L, Chen P-K. Comorbidities of migraine. Front Neurol. 2010;1:16.

- Ifergane G, Buskila D, Simiseshvely N, et al. Prevalence of fibromyalgia syndrome in migraine patients. Cephalalgia. 2006;26:451–456.

- Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1545–1602.

- Woldeamanuel YW, Cowan RP. Migraine affects 1 in 10 people worldwide featuring recent rise: a systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based studies involving 6 million participants. J Neurol Sci. 2017;372:307–315.

- Stovner LJ, Andree C. Prevalence of headache in Europe: a review for the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain. 2010;11:289–299.

- Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Katsarava Z, et al. The impact of headache in Europe: principal results of the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain. 2014;15:31.

- Vo P, Paris N, Bilitou A, et al. Burden of migraine in Europe using self-reported digital diary data from the migraine buddy(c) application. Neurol Ther. 2018;7:321.

- Stovner LJ, Andree C, Eurolight Steering C. Impact of headache in Europe: a review for the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain. 2008;9:139–146.

- Gürsoy AE, Ertaş M. Prophylactic treatment of migraine. Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 2013;50:S30–S35.

- Antonaci F, Ghiotto N, Wu S, et al. Recent advances in migraine therapy. Springerplus. 2016;5:637–650.

- Lipton RB, Silberstein SD. Episodic and chronic migraine headache: breaking down barriers to optimal treatment and prevention. Headache. 2015;55:103–122; quiz 23–26.

- Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337–1345.

- Hepp Z, Dodick DW, Varon SF, et al. Persistence and switching patterns of oral migraine prophylactic medications among patients with chronic migraine: a retrospective claims analysis. Cephalalgia. 2017;37:470–485.

- Berger A, Bloudek LM, Varon SF, et al. Adherence with migraine prophylaxis in clinical practice. Pain Pract. 2012;12:541–549.

- Hepp Z, Bloudek LM, Varon SF. Systematic review of migraine prophylaxis adherence and persistence. JMCP. 2014;20:22–33.

- Bloudek LM, Stokes M, Buse DC, et al. Cost of healthcare for patients with migraine in five European countries: results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). J Headache Pain. 2012;13:361–378.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33(9):629–808.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(Suppl 1):9–160.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Cephalalgia. 1988;8:1–96.

- Peterlin BL, Gupta S, Ward TN, et al. Sex matters: evaluating sex and gender in migraine and headache research. Headache. 2011;51:839–842.