Abstract

Aims: Nocturia (getting up at night to urinate, where each urination being followed by sleep or intention to sleep) is a bothersome symptom with potentially negative consequences for individual health and daytime functioning. This study assessed the burden of nocturia in the workplace by investigating associations between nocturia and subjective well-being (SWB), work engagement and productivity.

Methods: Using large-scale international workplace survey data, the associations between nocturia, SWB, work engagement (Utrecht Work Engagement Scale, UWES-9) and productivity (Work Productivity and Activity Impairment, WPAI) were assessed. Bivariate and multivariate regression analysis was used with adjustment for a large set of confounding factors, including sleep duration and sleep quality.

Results: Across a study sample of 92,129 observations, aged 18–70, an average of 10% of the survey population reported ≥2 nocturnal voids (generally considered clinically significant nocturia), with prevalence of nocturia increasing with age. Individuals with nocturia reported a 35.7% (p < .001) higher relative sleep disturbance score and were 10.5 percentage points (pp) (p < .001) more likely to report short sleep. Adjusted for covariates, nocturia was associated with a 3.5% (p < .001) lower relative SWB score and a 2% (p < .001) lower relative UWES-9 work engagement score. Nocturia was associated with a 3.9 pp (p < .001) higher work impairment due to absenteeism and presenteeism (WPAI). Adjusting additionally for sleep disturbance and sleep duration reduced the magnitude of the estimated effects, suggesting a key role for poor sleep in explaining the relationship between nocturia and the outcomes (SWB, UWES-9, WPAI) assessed.

Conclusions: A key contribution of this study is the assessment of the association between nocturia and a range of work performance outcomes in a sizeable study using validated instruments to measure work engagement and productivity. The study highlights the importance of taking sleep into account when assessing the relationship between nocturia and associated outcomes.

Introduction

Waking up at night to go to the bathroom interrupts sleep. The more frequent the nocturnal voids, the more bothersome it becomes for individualsCitation1. The International Continence Society (ICS) defines frequent night-time bathroom visits as nocturia, a lower urinary tract symptom (LUTS)Citation2. Evidence suggests that less than two nocturnal voids are usually not regarded as having clinically significant nocturia that warrants a diagnostic or clinical investigation or treatmentCitation3,Citation4. In this study, therefore, we use the frequently applied definition of nocturia as the need to urinate at least twice during the night (e.g. Andersson et al.Citation5).

There are different etiologies of nocturia caused by different factors. Among the most common are a large urine volume produced during the night (nocturnal polyuria), as well an overactive bladder (OAB) or benign prostatic obstruction (BPO)Citation3,Citation6,Citation7. Nocturia is relatively common, affecting on average up to 20% of the overall population, with prevalence increasing with ageCitation3. There also tends to be a higher prevalence in young women than young men, which is reversed with older ageCitation3,Citation8.

Nocturia has been associated with adverse health consequences such as increased risk for depression, cardiovascular disease, reduced quality of life, poor sleep, increased mortality risk and – in older individuals – a higher risk of injury through fallsCitation9. However, often people are reluctant to report nocturia until it becomes unbearable and substantially affecting their quality of lifeCitation10. Due largely to the complaint of disrupted sleep, the consequences of nocturia extend to the daytime, and specifically the workplace, as well. Nocturia has been associated with daytime fatigue, cognitive impairment and lower workplace productivity, measured through work impairment due to absenteeism and/or presenteeismCitation8. However, quantitative analysis linking work performance outcomes and nocturia is very limited.

The objectives of this observational study are, therefore, to assess the associations between nocturia and performance at work, including work engagement, productivity and subjective well-being (SWB). While a few studies have quantitatively linked nocturia with productivity and SWBCitation11,Citation12, the interpretation of their findings is limited due to the inability to consistently control for variables that relate to nocturia and work performance simultaneously. These include, among others, comorbidities, lifestyle factors and sleep. Specifically, the inclusion of sleep as a covariate in the analysis is important given that sleep is known to be associated with nocturia as well as work performance and SWBCitation13,Citation14. To address these limitations, we examined nocturia as a factor of workplace performance using large international cross-sectional workplace survey data of working age men and women, and statistically controlling for a host of covariates that may confound associations, including sleep duration and quality.

Methods

Study design

This cross-sectional observational study combined two unique datasets that linked employer-employee data: (i) vitality UK’s Britain’s Healthiest Workplace (BHW) survey,i covering the United Kingdom and (ii) AIA’s Asian Healthiest Workplace (AHW) survey,ii covering Australia, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Thailand, Singapore and Sri Lanka.

Both cross-sectional internet-based workplace surveys were administered by organizations to their workforces. The surveys’ goal was to collect information across many aspects of health and well-being, and broadly ask similar sets of question, across the seven different countries. Organizational participation in the surveys was advertised in national newspapers and in networks (e.g. client base of insurance and benefits companies) and was open to most organizations with 20 or more employees. Questionnaires were translated from English into local languages by professional translators local to the countries for which each survey was conducted. To provide a translation closely resembling the original survey instrument, the translators were aware of the concepts the questionnaire intended to measure. For the survey instruments where a validated translation was available (e.g. Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI), Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES), Kessler Psychological Distress Scale), the language-specific instrument was applied.

Organizations, and their employees, voluntarily participated. The surveys support employees to understand their health and well-being via a personalized individual report while providing a comprehensive aggregated report to organizations to support their well-being strategies and improvement for productivity. At the level of each participating organization, participation among employees was encouraged through emails, newsletters and direct engagement with human resource (HR) managers. Employees were surveyed with over 100 questions related to demographic factors (e.g. age, gender, education, and income), lifestyle behavior (e.g. nutrition, smoking habits, physical activity, and sleep behavior), health factors (e.g. mental and physical health indicators, chronic and musculoskeletal conditions), SWB as well as measures including workplace engagement and productivity.

All survey participants provided electronic written consent for anonymized usage of their records for research purposes as required. The data anonymization and usage comply with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The Ethics Committee at the data collecting organization RAND Europe has reviewed and approved the data collection and research plan. Furthermore, as part of their scientific affiliation with RAND Europe, the University of Cambridge (United Kingdom) reviewed ethical considerations for the BHW survey, and the National University of Malaysia provided ethics approval for the AHW survey.

Study population

In the statistical analysis, for both the BHW and AHW surveys, two annual waves for the years 2017 and 2018 were included with a total number of responses of 93,432. Excluding responses with missing data and pregnant female respondents, the final data sample consisted of 92,179 responses, covering employed individuals aged 18–70. Figure S1 illustrates the criteria for inclusion in the study samples. About 38% of total respondents included were from the AHW survey and 62% from the BHW survey.

The average response rates among employees in participating organizations was between 33% (BHW) and 41% (AHW), which were broadly in-line with response rates for similar type of surveysCitation15. The mean respondent age was 35 in AHW and 39 in BHW. Furthermore, about 60% of respondents in the AHW survey were female, compared to 50% in the BHW survey.

Measures and survey instruments

Sociodemographic and general health characteristics

Based on the existing literature on nocturiaCitation3,Citation16,Citation17, and the information available in the AHW and BHW surveys, the analyses included the following sociodemographic variables: age, gender, ethnicity, education, income, irregular working hours (e.g. night shifts), marital status and children (aged ≤18) living in the same household. Furthermore included were the following health characteristics: body mass index (BMI), smoking status (current smoker), physical inactivity (performing less than 150 min per week), excessive salt intake (adding regularly more than a pinch of salt to a meal), excessive alcohol consumption (drinking more than 14 alcohol units of 10 ml/8 mg per unit), and comorbid clinically diagnosed health conditions (cancer, asthma, heart disease, kidney disease, diabetes, and hypertension). A description of these sociodemographic and health variables is provided in Table S1.

Mental health was assessed through the Kessler Psychological Distress ScaleCitation18,Citation19. The six-item scale is a simple measure of psychological distress, involving six questions (each with a five-level response scale from 0 to 4) about different emotional states. In line with previous research, a dichotomous variable was generated taking the value one if the overall Kessler score is above 13, which is generally applied as the threshold of medium to severe psychological distress and anxietyCitation20.

Nocturia and sleep measures

Focusing on nocturia, the survey questions were based on related medical studies and applied standard scales collected from voiding diaries, sleep diaries, and patient-report outcomes on sleep qualityCitation21–23. For example, both surveys included a question on the number of times the individual reports waking at night to visit the bathroom (“How often do you usually get up during the night to go to the bathroom?”).

Questions regarding sleep quality included self-reported measures drawn from the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQICitation24) (“During the last seven days, how would you rate your sleep quality”; 0 very poor – 4 very good). This was followed by three additional questions, on a five-point scale (0 not at all – 4 very much), which assess whether during the last seven days: (1) the sleep was refreshing; (2) the individual had a problem with sleep; or (3) had difficulties falling asleep. Each of the four sleep-quality items have been recoded so that higher values represent a lower sleep quality. Following the approach taken in previous research (e.g. Troxel et al.Citation25), a summary measure of sleep disturbance was created by summing the four items into a single composite score ranging from 0 to 16, with a larger score corresponding to higher sleep disturbance.

As an additional measure for sleep quality, respondents were asked about the first uninterrupted sleep period (FUSP) measured in hours. As nocturnal voiding often occurs within the first two to three hours of sleep onset, potentially negatively affecting stages 3 and 4 of restorative non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, a shorter FUSP is thought to be an indicator of lower quality sleep. In addition, the level of tiredness or fatigue during wake time was assessed on a five-point scale (0 rarely ever – 4 almost every day), with a larger score corresponding to higher levels of fatigue. Lastly, sleep duration was assessed through the average number of hours of sleep per night, which was coded into three binary sleep duration variables (≤6 h; 6–9 h; ≥9 h) measuring short, normal and long sleep duration.

Subjective well-being

The AHW and BHW surveys included a question regarding the overall SWB of an individual, representing a standard measure applied in numerous studies on SWBCitation26 (“How satisfied are you with your life nowadays? 0 not at all – 10 completely). A higher score corresponds to a higher level of SWB.

Utrecht Work Engagement Scale

Work engagement was assessed using the short nine-item Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9), which includes three dimensions of work engagement: vigor, dedication, and absorptionCitation27. The nine questions related to the scale were measured on a seven-point Likert scale (0 never – 6 always). The total nine-item score as indicator for work engagement was used, ranging from 0 to 54, with a larger score corresponding to a larger level of work engagement.

Work Productivity and Activity Impairment

Productivity was assessed using the WPAI Questionnaire. The WPAI is a tool to quantify productivity loss by measuring the effect on work productivity of general health and symptom severityCitation28. The instrument consists of six questions with a recall time frame of seven days. The questions asked the respondent about the number of hours missed from work; the number of hours worked; and the degree to which the respondent feels that a health problem has affected productivity while at work and their ability to do daily activities other than work. WPAI outcomes were expressed as impairment percentages, either due to absenteeism or presenteeism or both, where higher percentages indicate greater impairment and lower productivity.

Statistical analysis

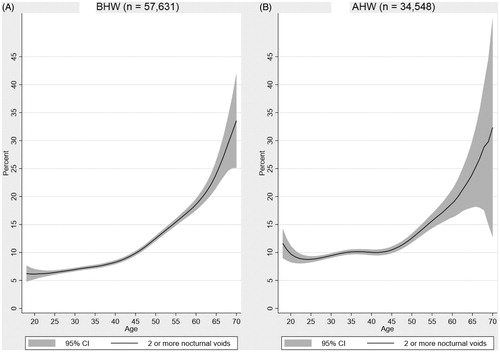

Three types of analyses were conducted. First, descriptive analyses were performed on the overall prevalence of clinically significant nocturia (≥2 nocturnal voids) across the two sample populations (BHW and AHW) by age and stratified further by gender. Chi-square tests were used to assess significant differences in the prevalence of nocturia within age groups across different sample populations. Furthermore, the prevalence of nocturia across the age distribution was plotted using a semi-parametric local polynomial estimation with Epanechnikov kernel and bandwidth of 5.

Second, we descriptively compared the non-nocturia and nocturia survey populations (0–1 vs. ≥2 nocturnal voids) with respect to sociodemographic and health characteristics, sleep quality and sleep duration, as well outcomes of interest (SWB, UWES-9, and WPAI). Chi-square tests were used to assess significant differences in categorical variables and Mann–Whitney’s tests to assess differences in continuous variables.

Third, we used multivariate generalized linear models (GLMs) to assess the difference between outcomes (SWB, UWES-9, and WPAI) for individuals with clinically significant nocturia and individuals without clinically relevant nocturia symptoms. All multivariate regression models were adjusted for sociodemographic and health characteristics. We also performed separate regression analyses which additionally adjusted for the sleep disturbance score and dummy variables for short and long sleep duration as additional covariates. We specified a Gaussian distribution, with identity link, in the GLMs for normally distributed outcomes (SWB and UWES-9). Furthermore, we specified a negative binomial distribution with log-link for outcomes with skewed distributions (WPAI). To mitigate the potential issue of employer selection bias into the AHW and BHW surveys, we included company identifier dummy variables in all GLMs and therefore only exploit variation across employees within the different organizations participating. All GLMs further included dummy variables for the week, month and year of the survey response given. For pooled regression analyses, based on the combined BHW and AHW samples, country dummy variables were included. We report Bonferroni’s corrected adjusted means, differences to the adjusted means across nocturia sub-groups, confidence intervals and p values.

For all analyses, statistical significance was assessed at a significance level of .05 and all statistical analyses were conducted in STATA 16 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Survey participants and nocturia prevalence

reports that across both samples, 9.5% (BHW) and 10.2% (AHW) of respondents report clinically significant nocturia (i.e. ≥2 nocturnal voids), but some significant differences are observed within age groups between the samples when stratified by gender. Across most age groups, nocturia prevalence among women tends to be higher than for men and prevalence is increasing with age ().

Figure 1. Prevalence of clinically significant nocturia (≥2 nocturnal voids) stratified by age, without adjustment. Abbreviations. BHW, Britain’s Healthiest Workplace survey; AHW, Asian’s Healthiest Workplace survey. Plotted using a semi-parametric local polynomial estimation with Epanechnikov kernel and bandwidth of 5.

Table 1. Prevalence of clinically significant nocturia (≥2 nocturnal voids) by age and gender, without adjustment.

reports that individuals with nocturia exhibit lower income and are more likely to work irregular hours. Furthermore, nocturia is associated with obesity, comorbid chronic health conditions (asthma, heart disease, kidney disease, diabetes, and hypertension) and higher levels of psychological distress and anxiety.

Table 2. Sociodemographic, health and lifestyle characteristics by number of reported nocturnal voids (0–1 vs. ≥2), without adjustment.

Bivariate associations between nocturia and sleep

Clinically significant nocturia is positively associated with short and long sleep duration, as well as lower sleep quality (). On average, individuals reporting two or more nocturnal voids are 10.5 percentage points (pp) (p < .001) more likely to be short sleepers (BHW: 13.2 pp; AHW: 5.5 pp) and 0.3 pp (p < .001) more likely to be long sleepers (BHW: 0.2 pp [p=.0287]; AHW: 0.5 pp [p < .001]). The mean sleep disturbance score is 1.5 (p < .001) higher among individuals with nocturia (BHW: 1.6 [p < .001]; AHW: 1.3 [p < .001]), corresponding to a 35.7% (=1.5/4.2) higher relative sleep disturbance score. The mean reported FUSP is 1 h (p < .001) shorter, (BHW: 1.3 h [p < .001]; AHW: 0.7 h [p < .001]). Furthermore, individuals with nocturia report on average a 0.2 (p < .001) higher daytime fatigue score (BHW: 0.3 [p < .001]; AHW: 0.1 [p < .001]), corresponding to a 6.9% (=0.2/2.9) higher relative score.

Table 3. Bivariate associations between clinically significant nocturia (≥2 nocturnal voids) and sleep.

Nocturia and associated outcomes (SWB, UWES-9, and WPAI)

Bivariate associations

reports that, without adjusting for covariates, clinically significant nocturia is associated with lower SWB and work engagement and higher levels of work impairment due to absenteeism and/or presenteeism. On average, individuals reporting two or more nocturnal voids report a –0.4 (p < .001) lower SWB score (BHW: −0.4 [p < .001]; AHW: −0.2 [p < .001]) than individuals reporting less nocturnal voids. This corresponds to a 5.8% (= −0.4/6.9) lower relative SWB score. In terms of work engagement, the UWES-9 score is –0.7 lower (p < .001) among individuals with nocturia (BHW: −1.0 [p < .001]; AHW: −0.2 [p=.132]), corresponding to a 2.1% (= −0.7/32.9) lower relative UWES-9 score. Unadjusted for covariates, total work impairment is 5.8 pp (p < .001) higher for individuals with nocturia (BHW: 5.9 pp [p < .001]; AHW: 5.4 pp [p < .001]).

Table 4. Bivariate associations between clinically significant nocturia (≥2 nocturnal voids), subjective well-being, work engagement and productivity.

Associations adjusted for socio-demographic and health characteristics, and sleep

reports the associations between nocturia and SWB, UWES-9 and WPAI outcomes adjusted for confounding factors. Adjusted for sociodemographic and health characteristics, the SWB score is on average –0.238 (p < .001) lower for individuals with nocturia (BHW: −0.243 [p < .001]; AHW: −0.212 [p < .001]), corresponding to a –3.5% (=–0.238/6.9) lower relative SWB score. Adjusting additionally for sleep disturbance, short, and long sleep duration reduces the magnitude of the relative difference in the SWB score to –0.031 (p=.103), rendering it to be statistically insignificant (BHW: −0.036 [p=.140]; AHW: −0.014 [p=.655]).

Table 5. Associations between clinically significant nocturia (≥2 nocturnal voids) and outcomes (SWB, UWES-9, and WPAI), adjusted for sociodemographic and health characteristics and poor sleep.

The adjusted UWES-9 score is –0.657 (p < .001) lower for individuals with nocturia (BHW: −0.636 [p < .001]; AHW: −0.662 [p < .001]), which corresponds to about a –2% (=–0.657/32.9) lower relative UWES-9 score. Adjusting additionally for sleep disturbance, short, and long sleep duration reduces the magnitude of the relative difference in the UWES-9 score to –0.073 (p=.448) (BHW: −0.051 [p=.694]; AHW: −0.092 [p=.494]).

Similar to the findings for the SWB and UWES-9 scores, adjusting for covariates reduces the magnitude of the relative difference in WPAI. Total work impairment due to absenteeism and presenteeism is 3.9 pp (p < .001) higher in the pooled sample (BHW: 3.4 pp [p < .001]; AHW: 4.3 pp [p < .01]) when adjusted for sociodemographic and health characteristics. Adjusting additionally for the sleep disturbance score and the short and long sleep duration dummy variables, the magnitude of the relative difference in total work impairment reduces further to 1.8 pp (p < .001) for individuals with nocturia (BHW: 1.6 pp [p < .001]; AHW: 1.9 pp [p < .001]). Thus, assuming a 35-hour working week, a full-time employed individual with nocturia loses weekly on average about 0.6 (=0.018 × 35) hours of work more than an individual reporting less than two nocturnal voids.

Distinguishing the associations between nocturia and total work impairment by different age groups reveals that the relative magnitude of the effect is larger for younger individuals than for older individuals with nocturia (Table S2). For the pooled sample, individuals aged 18–30 report on average a 2.8 pp (p < .001) higher total work impairment (BHW: 3 pp [p=.002]; AHW: 2.5 pp [p=.04]). In contrast, individuals aged 50–70 report on average a 0.9 pp (p=.012) higher total work impairment than individuals in the same age group without nocturia (BHW: 0.8 pp [p=.042]; AHW: 1.3 pp [p=.062]).

Discussion

This study directly contributes to the emerging evidence that examines nocturia as a symptom with adverse implications not only for the elderly (e.g. age 65 or above) but with potentially also negative consequences for young and middle-aged individuals in terms of lower SWB and performance at work. Except for a few studies, such as the Finnish National Nocturia and Overactive Bladder StudyCitation1,Citation17 and the Boston Area Community Health SurveyCitation29, there is limited evidence from population-based studies of all ages and both genders on the effects of nocturia.

To the best of our knowledge, the combined international workplace survey data used in this study represent the largest observational survey data on nocturia in employed non-patient populations. The findings of the study underscore the prevalence and importance of nocturia, and a key contribution is the assessment of the association between nocturia and a range of work performance outcomes using validated instruments to measure work engagement and productivity. The strength of this study is the demonstration that these negative consequences persist even after adjusting for many relevant covariates, highlighting the importance of taking poor sleep into account when assessing the relationship between nocturia and associated outcomes. Especially, the calculations of work impairment due to absenteeism and presenteeism are relevant for future calculations of the economic burden of nocturia.

Previous studies assessing the association between nocturia and work impairment using the WPAI instrument reported 8–39 pp higher relative total work impairment for individuals with clinically significant nocturia compared to individuals without nocturia symptomsCitation11,Citation12. However, these studies were limited to very small sample sizes or the inability to adjust the analysis for confounding factors. A novel finding of this study is that nocturia is indeed associated with a statistically significantly higher work impairment due to absenteeism and presenteeism, even after controlling for many sociodemographic and health characteristics, but the estimated magnitude of the associations is substantially lower than previous estimates. For instance, the analyses conducted in this study suggest that after adjusting for sociodemographic and health characteristics total work impairment for individuals with nocturia is on average 3.9 pp larger, with some variation across the two regional data samples (BHW: 3.4 pp; AHW: 4.3 pp). The relative magnitude of these associations tends to be larger for younger individuals (e.g. aged 18–30) than for older individuals (e.g. aged 50–70). In addition to the association with work impairment, there is evidence that nocturia is associated with lower SWB (SWB score) and lower work engagement (UWES-9 score).

Another novel aspect of this study is the ability to adjust for poor sleep as confounding factor in the analysis. With the exception of a few studiesCitation8,Citation30, other studies have failed to address the potential confounding factor of sleep, which is critical due to the known association between nocturia and sleep disruption. It is well documented that poor sleep is associated with adverse effects on work performance and SWBCitation13 and the findings of the multivariate regressions performed in this study indeed suggest that the association between nocturia, well-being and productivity outcomes might be best understood as reflecting the effects of poor sleep. That is, the magnitude of the associations between nocturia, the SWB score, UWES-9 score and work impairment (WPAI) were substantially reduced by adjusting for sleep disturbance and sleep duration in the regression models, suggesting that sleep is a key underlying factor in the relationship between nocturia and the outcome variables examined.

However, the bidirectional relationship between sleep and nocturia cannot be causally established with the nature of the observational cross-sectional data. For instance, disrupted sleep could be caused by other factors such as sleep apnea, which contributes to sleep fragmentation, and has been associated with nocturia episodes and increased urine productionCitation31,Citation32. Some descriptive evidence has suggested that poor sleep quality could be a predictor of nocturia, but longitudinal data also support the reverse direction; that nocturnal voiding is strongly predictive of poor sleep qualityCitation33. Overall, while this study cannot fully tease apart the directionality of the relationship between nocturia and poor sleep, which is an important area for future research, the empirical evidence presented in this study suggests that poor sleep likely plays a major role for the bidirectional relationship between nocturia and associated outcomes.

Overall, the nocturia prevalence in this non-patient population data corresponds to the population prevalence of two or more nocturnal voids suggested in previous studiesCitation3, with about 10% of the employed population across seven countries in our study sample experiencing the impact of nocturia. Our findings further suggest that the prevalence of nocturia may vary across different geographies, age and gender groups, which should be considered, and adjusted for, when analyzing the potential consequences of nocturia in future research. The descriptive results () on the sociodemographic and health characteristics associated with nocturia (e.g. income, irregular working hours, BMI, comorbid chronic health conditions) are in line with a comprehensive review of studies which have looked at correlates for nocturiaCitation16 and is aligned with the recent consensus paper from the ICS on the diagnosis and treatment of nocturiaCitation34.

Limitations

The present survey data and analysis have several strengths, such as the large sample size and comprehensive collection of data on sociodemographic and health characteristics, as well as measures of poor sleep, allowing an in-depth investigation of the association between nocturia and a variety of outcomes. Other strengths are its relevance and geographical scope due to coverage of different regions such as the United Kingdom, Asia and Australia, reflecting diversity and potentially different views on nocturia, sleep, SWB and work performance. However, there are some limitations to the empirical approach.

First, it is important to stress that all data are self-reported. This creates potential for the under-reporting of the real prevalence of certain lifestyle habits – such as smoking or alcohol consumption – or for overstating others, as physical activity for instance. Furthermore, while efforts have been made to linguistically and culturally adapt the questionnaires when translating them into local languages, it is important to highlight that due to the translation the validity of some of the survey measures used may not be guaranteed.

Second, as we define the nocturia population based on the self-reported frequency of nocturnal bathroom visits, the main variable in the analysis may be subject to inaccuracies since it has not been clinically diagnosed by a health professional and no bladder diary has been used to diagnose nocturia (e.g. as recommended by Hashim et al.Citation2) Furthermore, the nocturia variable used in the analysis does not allow for a differentiation of possible etiologies of nocturia (e.g. nocturnal polyuria or low bladder capacity, or other conditions where it is present). However, in contrast to nocturia-specific patient surveys, this study focused on the associations between nocturia, poor sleep and outcomes such as SWB, work engagement and productivity, and the survey data cover a broad array of health and workplace topics, and thus would probably not be subject to response bias based on nocturia itself.

Third, SWB is measured using a single question. While this question has been used in many studies to assess the overall life satisfaction of an individual, it is important to highlight that SWB is indeed a complex construct which may not be measured adequately with one single item. Using other SWB tools such as the BBC-SWB scale or the Well-Being Scale (WeBS) would provide a more nuanced analysis on the association between nocturia and SWB.

Fourth, the sleep disturbance summary measure used in the analysis is partly based on validated sleep instruments such as the PSQI and consistent with the Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS) sleep disturbance instrumentsCitation35. However, it is important to highlight that the summary measure itself is not validated and hence the psychometric properties to measure sleep quality are not guaranteed.

Fifth, the response rates are average for organizational surveys conducted online, however, a larger response rate would have been generally beneficial. Furthermore, due to the internet-based data collection, there is a risk that respondents to both surveys were generally younger and more tech-savvy than the patient sample populations in previous nocturia research. It is also important to highlight that these survey data cover only employed individuals and findings of the study may not be directly applied to people currently not in the workforce.

Sixth, when interpreting the results, caution should be applied with regards to causality. Our statistical regression models capture associations and not necessarily causation. While each multivariate regression model adjusts for a large set of covariates, there is a possibility that reverse causality is an issue. For instance, when we examine the association between nocturia and sleep, it is not a priori clear in which direction this relationship holdsCitation33.

Finally, even though the data and the regression analysis include corrections for many potential confounders, we may have overlooked some underlying comorbidities and lifestyle factors.

Conclusions

Given nocturia’s potential negative consequences on sleep and daytime functioning, understanding the consequences of nocturia in younger populations, especially those in the working-age is important from a wider societal point of view, as it not only negatively affects individuals’ quality of life but potentially also has negative ramifications for their performance at work. The findings of this study emphasize that nocturia is a debilitating symptom that affects a broad age range in the population, including working adults. These findings highlight the considerable individual and societal burden of nocturia, and future research is encouraged to assess the economic burden of the nocturia-related work performance impairment.

Transparency

Declaration of financial/other relationships

FLA is an employee of International PharmaScience Center, Ferring Pharmaceuticals A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark; TB is an employee of Ferring International Center S.A., Saint-Prex, Switzerland. The other authors declare no financial interest.

JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work, but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

JME-2020-0049-FT.R1_supplement_CATS.docx

Download MS Word (65.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank Nadja Koch from RAND Europe for her research assistance. The BHW and AIA workplace surveys are conducted and collected by RAND Europe for Vitality UK and AIA. Vitality UK and AIA have given permission to use the data for this research, but they had no role in the analyses of the study or the preparation of the manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

References

- Agarwal A, Eryuzlu LN, Cartwright R, et al. What is the most bothersome lower urinary tract symptom? Individual- and population-level perspectives for both men and women. Eur Urol. 2014;65(6):1211–1217.

- Hashim H, Blanker MH, Drake MJ, et al. International Continence Society (ICS) report on the terminology for nocturia and nocturnal lower urinary tract function. Neurourol Urodyn. 2019;38(2):499–508.

- Bosch JL, Weiss JP. The prevalence and causes of nocturia. J Urol. 2010;184(2):440–446.

- Tikkinen KA, Johnson TM 2nd, Tammela TL, et al. Nocturia frequency, bother, and quality of life: how often is too often? A population-based study in Finland. Eur Urol. 2010;57(3):488–496.

- Andersson F, Anderson P, Holm-Larsen T, et al. Assessing the impact of nocturia on health-related quality-of-life and utility: results of an observational survey in adults. J Med Econ. 2016;19(12):1200–1206.

- Weiss JP. Nocturia: focus on etiology and consequences. Rev Urol. 2012;14(3–4):48–55.

- Cornu JN, Abrams P, Chapple CR, et al. A contemporary assessment of nocturia: definition, epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2012;62(5):877–890.

- Bliwise DL, Wagg A, Sand PK. Nocturia: a highly prevalent disorder with multifaceted consequences. Urology. 2019;133S:3–13.

- Weidlich D, Andersson FL, Oelke M, et al. Annual direct and indirect costs attributable to nocturia in Germany, Sweden, and the UK. Eur J Health Econ. 2017;18(6):761–771.

- Marinkovic SP, Gillen LM, Stanton SL. Managing nocturia. BMJ. 2004;328(7447):1063–1066.

- Kobelt G, Borgstrom F, Mattiasson A. Productivity, vitality and utility in a group of healthy professionally active individuals with nocturia. BJU Int. 2003;91(3):190–195.

- Miller PS, Hill H, Andersson FL. Nocturia work productivity and activity impairment compared with other common chronic diseases. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(12):1277–1297.

- Swanson LM, Arnedt JT, Rosekind MR, et al. Sleep disorders and work performance: findings from the 2008 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America poll. J Sleep Res. 2011;20(3):487–494.

- Hafner M, Stepanek M, Taylor J, et al. Why sleep matters-the economic costs of insufficient sleep: a cross-country comparative analysis. Rand Health Q. 2017;6(4):11.

- Mellahi K, Harris LC. Response rates in business and management research: an overview of current practice and suggestions for future direction. Br J Manage. 2016;27(2):426–437.

- Yoshimura K. Correlates for nocturia: a review of epidemiological studies. Int J Urol. 2012;19(4):317–329.

- Tikkinen KAO, Auvinen A, Johnson TM, et al. A systematic evaluation of factors associated with nocturia—the population-based FINNO Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(3):361–368.

- Kessler R, Mroczek D. Final versions of our Non-Specific Psychological Distress Scale [memo dated 10/3/94]. Ann Arbor (MI): Survey Research Center of the Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 1994.

- Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32(6):959–976.

- Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184–189.

- Carney CE, Buysse DJ, Ancoli-Israel S, et al. The consensus sleep diary: standardizing prospective sleep self-monitoring. Sleep. 2012;35(2):287–302.

- Romano CD, Lewis S, Barrett A, et al. Development of the Nocturia Sleep Quality Scale: a patient-reported outcome measure of sleep impact related to nocturia. Sleep Med. 2019;59:101–106.

- Hsu A, Nakagawa S, Walter LC, et al. The burden of nocturia among middle-aged and older women. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):35–43.

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index – a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213.

- Troxel WM, Buysse DJ, Hall M, et al. Marital happiness and sleep disturbances in a multi-ethnic sample of middle-aged women. Behav Sleep Med. 2009;7(1):2–19.

- Blanchflower DG. International evidence on well-being. Discussion paper no. 3354. Bonn, Germany: Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA); 2008.

- Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, Salanova M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire – a cross-national study. Educ Psychol Meas. 2006;66(4):701–716.

- Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4(5):353–365.

- Kupelian V, Wei JT, O'Leary MP, et al. Nocturia and quality of life: results from the Boston Area Community Health Survey. Eur Urol. 2012;61(1):78–84.

- Choi EPH, Wan EYF, Kwok JYY, et al. The mediating role of sleep quality in the association between nocturia and health-related quality of life. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17(1):181.

- Endeshaw Y. Correlates of self-reported nocturia among community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(1):142–148.

- Miyazato M, Tohyama K, Touyama M, et al. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure on nocturnal urine production in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36(2):376–379.

- Araujo AB, Yaggi HK, Yang M, et al. Sleep related problems and urological symptoms: testing the hypothesis of bidirectionality in a longitudinal, population based study. J Urol. 2014;191(1):100–106.

- Everaert K, Herve F, Bosch R, et al. International Continence Society consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of nocturia. Neurourol Urodyn. 2019;38(2):478–498.

- Yu L, Buysse DJ, Germain A, et al. Development of short forms from the PROMIS™ sleep disturbance and sleep-related impairment item banks. Behav Sleep Med. 2011;10(1):6–24.