Abstract

Background

Neuroblastoma (NB) is notorious in childhood cancer because of its high incidence and poor prognosis. The Children’s Oncology Group reported that the 3-year OS in the high-risk (HR) group is 50%, and the HR-NB with bone marrow metastasis in our center is 43.1%. Thousands of families in China suffer from the cost of NB, but the true costs of therapy are unknown; to date, no study has ever performed a detailed therapy costs analysis for NB. The objective of this study was to assess the economic burden of NB treatment in children to the family, to ultimately reduce related expenses for patients and promote the establishment of NB management policy.

Materials and methods

Data in this cross-sectional study were collected via questionnaires completed by parents at the outpatient clinic and was verified via a computer system. Therapy costs of children with NB of differing risks were analyzed through descriptive statistics (1 CNY ≈ 0.1412 USD).

Results

Median direct medical costs of low risk (LR), middle risk (MR), and HR NB during treatment were 180.0 (120.0, 300.0), 200.0 (166.0, 300.0), and 650.0 (415.5, 850.0) thousand Chinese yuan (CNY), respectively. Direct non-medical costs including transportation, food, and accommodation were 60.0 (37.0, 100.0), 80.0 (60.0, 120.0), and 100.0 (80.0, 157.5) thousand CNY in the LR, MR, and HR groups, respectively. Additionally, parents accrued work absences to attend treatment, and lost a total of 100.0 (50.0, 150.0) thousand CNY in indirect costs.

Limitations

Families whose children had relapsed or died were excluded from this analysis and therefore limited the conclusions drawn. Parents were asked to recall costs since initial diagnosis (1–6 years in the past), but this extended time period may have introduced recall bias.

Conclusions

Direct non-medical and indirect costs play an important role in the total treatment costs of NB. Children with NB treated in local hospitals and followed up in hospital specialized in childhood oncology may save many unnecessary expenses. China's healthcare system should establish mechanisms and provide financial support for children with NB.

Background

Neuroblastoma (NB) is the most common extracranial solid tumor in children, accounting for 3–8% of all malignant tumors before the age of 15Citation1. In recent years, patients with NB have achieved a certain level of treatment success, mainly through surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and immunotherapyCitation2. With the development of immunotherapy and targeted drugs such as chimeric antigen receptor-transduced T cells and I-metaiodobenzylguanidine, therapy costs have increased alongside the survival rateCitation3,Citation4.

The economic burden of NB consists of direct and indirect costsCitation5. In turn, direct costs are divided into direct medical cost and direct non-medical cost. The former is defined as all costs of medical service, such as treatment, examination, continuing care, and sickbeds, among other resources. The latter includes non-medical expenses such as meals, accommodation, and transportation. Conversely, indirect costs, otherwise known as time costs, are the economic loss due to the family’s cessation of employment because of hospitalization. There is a wide gap between Chinese and European medical systems, with one example being the difference in the expected roles of general practitioners and family doctorsCitation6. Different countries administer healthcare in different ways (private insurance, public healthcare, a combination of the two). In China, there are also many types and complicated medical insurance. Method of NB reimbursement is similar to other child cancer. Depending on the type of insurance, drugs located in the National Drug Reimbursement Catalog can be reimbursed for different proportions. They generally have a minimum payment amount and an annual maximum limit. Native medical insurance has a higher reimbursement ratio than non-native medical insurance. Reimbursement ratio of outpatient costs is lower than hospitalization expense. However, due to the short period of popularization of the graded therapy system and the difficulty of NB treatment, most NB families prefer to be treated in non-native tertiary hospital. Therefore, patients in China are concentrated in first-tier cities, resulting in increasing overhead costs.

One Canadian study suggested that the average total cost incurred by families with NB over the course of treatment was $205,747Citation7. Tsimicalis et al. proposed the largest costs for children with cancer were travel and time previously allocated for unpaid activitiesCitation8. Another data reported that multidisciplinary therapy combined with low-cost adaptations such as modifying chemotherapy protocol, limiting clinical examination before autologous stem cell transplantation, decreasing stem cell cryopreservation conditions could reduce NB treatment costsCitation9. Children with cancer also have a negative impact on the quality of life of the family and the emotional health of parentsCitation10.

However, there has been no research on the detailed cost of NB in China to date, despite the country having the most NB cases worldwide. The objective of this study was to perform a therapy cost analysis for NB to the family, with the intention that the results can be used to promote the establishment of management policy for the diagnosis and treatment of NB in China and to help patients’ families reduce related expenses as much as possible.

Methods

Study setting

The study was conducted at the Hematology Oncology Center of Beijing Children’s Hospital (BCH) in Beijing, China and began in December 2018. Since 2006, we received approximately 400 new patients diagnosed with a solid tumor every year. We adopted a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis and treatment, and considerably improved the short-term effects of solid tumors. As the hospital with the largest number of children diagnosed with NB in China, we received 160 cases of NB in 2017 and a further 190 cases in 2018.

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study based in hospital. The data were collected by distributing questionnaires to parents at the outpatient clinic, and the objectivity of the information was verified through cross-check with the existing hospital data on hospitalization and outpatient expenses. In the case where the majority of data in the questionnaire and the system are not significantly different, we adopt the former because they also incurred costs in other hospitals during their treatment. For a very small number of patients with large differences, we selected the final data source via telephone. This study design was approved by the Beijing Children’s Hospital Institutional Ethics Committee (2019-35).

In this survey, direct medical costs were divided into treatment costs and follow-up costs, derived from drugs, registration, surgery, examination, treatment, hospitalization, consumables, external hospital examinations, and external hospital treatment. Direct non-medical costs included transportation, food, and accommodation expenses were categorized as. Indirect costs were measured as the loss of income from parents’ work absence while accompanying their childrenCitation5. Only children whose registered permanent residence is Beijing can have medical insurance for Beijing urban residents. Children registered in cities except Beijing can apply for medical insurance for foreign urban residents. New rural cooperative medical insurance is a medical insurance designed for rural population. Commercial insurance refers to private insurance that receives compensation from the enterprise.

Study participants

The study sample included children with NB diagnosed in the Hematological Oncology Center of BCH between 2012 and 2018. In order to discuss the cost of the entire NB treatment course, all patients completed treatment and were in complete remission of the disease. One hundred percent of eligible parents approached agreed to participate in the study. We distributed electronic questionnaires to parents who had given informed consent during outpatient follow-up. Each family chose a representative to complete the survey.

Questionnaire survey

A structured questionnaire was used to assess financial burden, developed by the author in consultation with oncologists, nurses, psychologists, and social workers (Supplemental file 2). The questionnaire consisted of 33 items that covered personal information, grouping and treatment stages of disease, disease-related costs, social security, and family impact. In order to ensure the accuracy of the data, we included 22 fill-in, 10 multi-choice, and one multi-answer question. Simultaneously, we had professional research executives available to answer questions at any time to help parents accurately fill out the questionnaire.

Management of NB

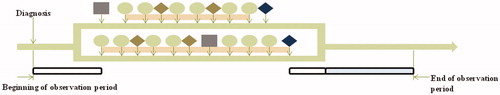

All the children enrolled according to different risk groups were treated according to the NB program (BCH-2007-NB) of BCH, affiliated with Capital Medical University. The time axis of regular treatment for high, middle, and low risk (LR) children in our center is shown in and and Supplemental file 1. Among them, children in the middle-low risk group adopted the chemotherapy regimen of CO (cyclophosphamide + vincristine), CBVP (carboplatin + etoposide), and CADO (cyclophosphamide + doxorubicin + vincristine). Intensive induction chemotherapy was alternated with CAV (cyclophosphamide + adriamycin + vincristine) and CVP (cisplatin + etoposide) in high-risk (HR) children. Participants also combined this treatment with surgical resection, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, local radiotherapy, 13-cis retinoid maintenance, immunotherapy, MIBG, and other multidisciplinary treatments.

Figure 1. The timeline of high-risk NB treatment.

Surgery;

Surgery;

Figure 2. The timeline of low-risk NB treatment.

Surgery;

Surgery;

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPSS, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) version 22. The economic and living burden of NB with differing risk on children's families was analyzed through descriptive statistics. Normally distributed quantitative data were described in the form of mean (standard deviation); otherwise, data were described using the median (upper and lower quartile). Frequency (percentage) was used for categorical variables. Costs were described by mean, median, upper and lower quartiles, and maximum and minimum values. According to 2019 bank's currency conversion rate, 1 CNY is approximately equal to 0.1412 USD.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 155 patients with NB participated in the study (), including 70 males (45.16%) and 85 females (54.84%). In total, 46 (29.7%) of patients were less than 1 year-old, 17 (11%) were between 1 and 1.5 years old, 71 (45.8%) were between 1.5 and 5 years old, and 21 (13.5%) were 5 years or older when diagnosed. The median age of onset was 28 (9, 46) months. For detailed risk grouping and follow-up information (see ).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of NB cases.

Direct costs

After assessment, there were 122 families with clear and reliable costs data. The median direct medical cost for all families during treatment was 300.0 (200.0, 612.5) thousand Chinese yuan (CNY), which included 180.0 (120.0, 300.0) thousand CNY for the LR group, 200.0 (166.0, 300.0) thousand CNY for the middle risk (MR) group, and 650.0 (415.5, 850.0) thousand CNY for the HR group. It could be seen that the direct medical cost during treatment in the HR group was significantly higher than that in the LR and MR group. The average cost per person for each follow-up was 6.0 (5.0, 10.0) thousand CNY. Among them, the LR group spent an average of 5.5 (4.8, 8.5) thousand CNY each time, while the MR group spent 7.0 (5.0, 10.0) thousand CNY, and the HR group spent 7.0 (4.9, 10.0) thousand CNY. This cost of the HR group was similar to that of the MR group, but higher than that of the LR group. This is because different groups of NB children have different tests during follow-up. Treatment alone accounted for 71.43% (61.16%, 79.79%) of total expenditure during each follow-up period.

To date, the mean cost of transportation, food, and accommodation for the patient and his entourage over the treatment course has amounted to 60.0 (37.0, 100.0), 80.0 (60.0, 120.0), and 100.0 (80.0, 157.5) thousand CNY in the LR, MR, and HR groups, respectively, as detailed in . This is obviously because the higher the malignancy, the longer the treatment time, the more direct non-medical costs incurred. Furthermore, 16 patients (10.32%) believed that these direct non-medical costs were reasonable and had enough property to pay, 81 (52.26%) found them unreasonable but could hardly afford, and 58 (37.42%) were unable to cope with the financial strain.

Table 2. Direct and indirect costs in different groups (thousand CNY)Table Footnoteb.

Indirect costs

When seeing a doctor, patients were accompanied by either one additional person (2.58%), two (74.84%), three (18.71%), four (3.23%), or five additional people (0.65%). Their main caregivers spent an average of 12 (10, 16) hours per day looking after and accompanying the children, with 12 (10, 15.75) hours spent for those with LR NB, 14 (12, 16) hours for MR NB, and 12.5 (11.25, 16) hours for HR NB. By accompanying the children, caregivers were absent from their work and lost a total of 100.0 (50.0, 150.0) thousand CNY, as shown in . Only the HR group had a higher cost than the MR and LR group because of the long treatment period and serious illness (100.0 (80.0, 200.0) vs. 80.0 (57.5, 100.0) vs. 80.0 (50.0, 110.0)).

Medical insurance and social security

Among these children, 101 (65.16%) were insured and 54 (34.84%) were not. Specific insurance policy categories and endurance capacity are shown in . Most policies were medical insurance for foreign residents (40.59%) and new rural cooperative medical insurance (44.55%). Sixty-one patients (60.40%) knew their reimbursement amount and 40 (39.60%) did not know. Of those 61 patients, they had so far been reimbursed a total of 40.0 (18.0, 130.0) thousand CNY. The LR group had been reimbursed 27.5 (1.8, 40.0) thousand CNY, the MR group 30.0 (16.5, 48.8) thousand CNY, and the HR group 130.0 (60.0, 200.0) thousand CNY.

Table 3. Insurance categories and endurance capacity for family with NB.

Discussion

Despite the biological and immunological characteristics of NB, such as high heterogeneity, difficult diagnosis, high recurrence rate, and easy escape from immune control, the survival rate of NB treatment has greatly improved in recent yearsCitation11,Citation12. This has been due to the emergence of Multiple Disciplinary Treatment and cooperation between the family members of the patient and the medical staff. Recent statistics from our center have shown that the overall 5-year survival rate of NB in the low-middle-risk group and the HR group is 86.7% and 38.9%, respectively, which is at the domestic leading level. With the improvement of social burdens and parents' medical awareness, newly diagnosed families are increasingly eager to understand the therapy costs of NB. However, there has been no study performed specifically on the detailed costs of NB treatment for children.

Most families in our study expressed reluctance or difficulty in accepting direct costs, especially direct non-medical expenses such as family transportation, accommodation, and meals at the time of entering the hospital. As the risk of NB increased, each cost for the family increased. This was consistent with results from a previous survey of the economic burden of other children in the world. According to a Lancet articleCitation13, the expenditure of newly diagnosed cancer patients (over fixed-time periods) in China accounted for 57.5% of the annual household income, creating financial difficulty for 77.6% of households. A New England group reported that the cost of treatment alone for a living child was NZ $220, about 13% of after-tax household income, while other expenses were much higherCitation14. Oliveira et al.Citation15 revealed that the cost of cancer in children was much higher than in adolescents and well above the reported cost of adults. For the initial, continuation, and final phases, net therapy costs per child for 1 year were $138,161, $15,756 and $316,303 respectively after reimbursement. Another study showed that in the first 12 months of treatment, except for the median total expenditure of $1,000 per household, additional financial burdens such as vehicle costs, air tickets, extra food, accommodation, and childcare, among others, were more burdensomeCitation16. In addition, many working parents are unable to manage the child's treatment, and ultimately choose one or even both parents to resign to accompany their children to the hospital. This has resulted in the indirect (related) costs of work absence. The more people that accompany the patient during treatment, the longer the work absence and the higher the related costs will be. Families of children with cancer face a variety of direct and time costs, the largest of which are travel and time previously allocated to unpaid activitiesCitation8. Parents usually have emotional and mental health burden leading to ongoing psychological problems because of heavy financial burden. Financial difficulties caused by cancer may also cause baseline low-income, single-parent status, longer treatment protocols, and receipt of care far from home. A report recommended that assessment of risk for financial hardship should be incorporated at time of diagnosis as a Standard of Care in Pediatric Oncology. Afterwards, the government and charities provide them with targeted financial counseling and supportive resourcesCitation10.

Only 13.86% of patients with NB had local health insurance; most patients came from outside Beijing and had to apply for reimbursement elsewhere. The proportion of local reimbursement and the minimum reimbursement amounts varied, and were accompanied by cumbersome procedures. Additionally, some newer treatments, such as foreign immunotherapy for children with NB, could not be reimbursed at all. In the United States, more than 2 million cancer survivors have experienced huge economic burdens due to lack of medical financial aid, seven mainly in Hispanic and African American householdsCitation17. Similarly, Mostert et al.Citation18 studied families in Kenya who gave up treatment and identified that the financial burden and lack of insurance for cancer treatment were important predictors of their abandonment. It obviously affected cancer cure rates in Kenya. Due to the high co-insurance rates in China, it is difficult for cancer patients to find a method to obtain financial resources and effectively manage their cancer burdenCitation19.

The above key findings have practical medical and social implications. First, families with children who are newly diagnosed or currently being treated for NB will gain the psychological preparation for future treatment costs and will be able to guide their next choice of medical services. Second, healthcare institutions will have access to favorable data. This will help them obtain supportive evidence and valid reasons for exhortations to divert patients. In addition, we anticipate that our findings will be useful for urging relevant government departments to pay more attention to pediatric oncology and its practical challenges. We hope those departments will establish more management for NB, such as increasing the proportion of NB reimbursement in different cities, reimbursing some medical expenses incurred abroad, popularizing NB-related knowledge in grass-roots institutions, changing the way that healthcare funding assessed and distributed, giving parents employment insurance or benefits to off-set the costs and so on. This may also encourage the publication of more social welfare and public medical deployment policies. More charities will focus on children with NB. Targeting referral for financial counseling for families with social workers and accessing charitable organizations is encouraged to explore. This study also provides background on the socioeconomic influence of the diagnosis and treatment of NB in China for pediatric oncology departments worldwide.

Limitations

Despite the many advantages of the data collected, there were still some shortcomings in this study. Considering the parents’ psychology and the reality of the study implementation, the researchers only selected patients with complete remission of the disease and did not include families whose children had relapsed or died. The questionnaire reminded parents of the cost since diagnosed (nearly 1–6 years), but this time period may have been too long and could have caused recall errors. And limited sample size and insufficient follow up time also became one of the shortcomings. In future investigations, we will focus on comparing the economic costs of children with NB diagnosed by early screening with post-morbid diagnosis, as well as the financial challenges of refractory and recurrent NB.

Conclusions

Direct non-medical costs and indirect costs play a significant role in the total therapy costs of NB. Patient with NB treated in local hospitals may avoid many unnecessary expenses, such as transportation, accommodation, meals, and lost earnings, and may even get more medical subsidies. China's healthcare system urgently needs to establish the appropriate mechanisms and introduce more policies for children with solid tumors, in addition to providing financial support for NB. It is also important to pay attention to the emotional and psychological health of NB families.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This work was funded by the Cultivation Projects of National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

CYJ and SYC are co-first authors and wrote the paper. XLM and XXP designed and reviewed the study. In addition, CD recruited the patients. NX and YCZ collected the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Complying with ethics of experimentation statement

Due to the nature of the questionnaire, all participants gave handwritten consent to participate in the study. This research was approved by the Beijing Children’s Hospital Institutional Ethics Committee (2019-35).

Supplemental Material File 1

Download MS Word (23.6 KB)Supplemental Material File 2

Download MS Word (19.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The thank the participating patients and their families. As all participants were under 16 years old, informed consent was obtained from their respective parents. Parents signed the informed consent form including publication requests, filled out the electronic version of the questionnaire, and delivered it to us online.

Data availability statement

The original dataset is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Steliarova-Foucher E, Colombet M, Ries LAG, et al. International incidence of childhood cancer, 2001–10: a population-based registry study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(6):719–731.

- Smith V, Foster J. High-risk neuroblastoma treatment review. Children (Basel). 2018;5(9):114.

- Maria Chimeno J, Sebastià N, Torres-Espallardo I, et al. Assessment of the dicentric chromosome assay as a biodosimetry tool for more personalized medicine in a case of a high risk neuroblastoma 131I-mIBG treatment. Int J Radiat Biol. 2018;95:1–13.

- Parihar R, Rivas CH, Huynh M, et al. NK cells expressing a chimeric activating receptor eliminate MDSCs and rescue impaired CAR-T cell activity against solid tumors. Cancer Immunol Res. 2019;7(3):363–375.

- Tsimicalis A, Stevens B, Ungar WJ, et al. The cost of childhood cancer from the family's perspective: a critical review. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56(5):707–717.

- Lu S, Ye M, Ding L, et al. Cost-effectiveness of gefitinib, icotinib, and pemetrexed-based chemotherapy as first-line treatments for advanced non-small cell lung cancer in China. Oncotarget. 2017;8(6):9996–10006.

- Oliveira CD, Bremner KE, Liu N, et al. Costs for childhood and adolescent cancer, 90 days prediagnosis and 1 year postdiagnosis: a population-based study in Ontario, Canada. Value Health. 2017;20(3):345–356.

- Tsimicalis A, Stevens B, Ungar WJ, et al. A prospective study to determine the costs incurred by families of children newly diagnosed with cancer in Ontario. Psychooncology. 2012;21(10):1113–1123.

- Jain R, Hans R, Totadri S, et al. Autologous stem cell transplant for high-risk neuroblastoma: achieving cure with low-cost adaptations. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(6):e28273.

- Pelletier W, Bona K. Assessment of financial burden as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(S5):S619–S631.

- Lee SI, Jeong YJ, Yu AR, et al. Carfilzomib enhances cisplatin-induced apoptosis in SK-N-BE(2)-M17 human neuroblastoma cells. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):5039.

- Fletcher JI, Ziegler DS, Trahair TN, et al. Too many targets, not enough patients: rethinking neuroblastoma clinical trials. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18(6):389–400.

- Huang HY, Shi JF, Guo LW, et al. Expenditure and financial burden for common cancers in China: a hospital-based multicentre cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2016;388(Special Issue):S10.

- Dockerty J, Skegg D, Williams S. Economic effects of childhood cancer on families. J Paediatr Child Health. 2003;39(4):254–258.

- Oliveira CD, Bremner KE, Liu N, et al. Costs of cancer care in children and adolescents in Ontario, Canada. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(11):e26628.

- Heath JA, Lintuuran RM, Rigguto G, et al. Childhood cancer: its impact and financial costs for Australian families. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2006;23(5):439–448.

- Weaver KE, Rowland JH, Bellizzi KM, et al. Forgoing medical care because of cost: assessing disparities in health care access among cancer survivors living in the United States. Cancer. 2010;116(14):3493–3504.

- Mostert S, Njuguna F, Langat SC, et al. Two overlooked contributors to abandonment of childhood cancer treatment in Kenya: parents' social network and experiences with hospital retention policies. Psychooncology. 2014;23(6):700–707.

- Sun XJ, Shi JF, Guo LW, et al. Medical expenses of urban Chinese patients with stomach cancer during 2002–2011: a hospital-based multicenter retrospective study. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):435.