Abstract

Aims

The study compared quality outcomes, resource utilization, and costs in Medicare beneficiaries with chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) with and without a worsening heart failure event (WHFE).

Methods

This retrospective observational study evaluated claims data for two cohorts of Medicare beneficiaries with chronic HFrEF who were enrolled in Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) or Medicare advantage (MA) plans. The index date was the first claim of HFrEF between October 2015 and September 2017. Patients with WHFE were identified if they had IV diuretic use or hospitalization for HF during 12 months after index date; with remaining patients classified as non-WHFE. During follow-up, starting from the 13th month after HFrEF index date to end of follow-up, generalized linear models were used to adjust for patient characteristics to compare mean per patient per year (PPPY) quality outcomes, resource utilization, and costs between HFrEF patients with and without WHFE

Results

Of the 1,182,509 FFS and 28,645 MA patients with HFrEF, 34.2% and 32.5% developed WHFE, respectively. Compared to patients without WHFE, patients with WHFE had higher rates of all-cause 30-day readmissions (FFS: 42% vs. 31%; MA: 41% vs. 31%), hospitalizations (FFS: 2.27 vs. 1.36; MA: 1.47 vs. 0.78 PPPY) and ED visits (FFS: 1.82 vs. 1.25; MA: 1.43 vs. 0.96 PPPY); all comparisons p < .05. Mortality rates in FFS patients were higher among patients with WHFE (34.3%) compared to those without (23.4%). All-cause total PPPY costs were higher for patients with WHFE compared to those without by $20,825 in FFS and $15,974 in MA. Similar trends were observed for HF-related outcomes.

Conclusion

Medicare patients with chronic HFrEF experiencing a WHFE had worse quality outcomes as well as higher resource utilization and costs compared to those without WHFE, thus, suggesting the need for better treatments and interventions to manage these patients.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a burdensome disease affecting approximately 6.5 million adult AmericansCitation1, with almost half of HF patients having reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF)Citation2. HFrEF is a progressive condition and a subset of HFrEF patients experience a worsening HF event (WHFE) characterized by escalating symptoms requiring treatment in an outpatient or inpatient settingCitation3–8. There is evidence that WHFE is associated with poor prognosis, worse clinical outcomes, and higher healthcare resource utilization (e.g. hospitalizations and readmissions) that generate substantially higher treatment-related costsCitation3–8. Among patients with chronic HFrEF following a WHFE, readmission rates are high, with 56% of patients readmitted within 30 days of a WHFECitation3. Readmissions have been a critical quality improvement focus for hospitals and health plans since the introduction of Medicare’s public reporting and value-based purchasing programs, potentially resulting in large penalties for higher-than-expected readmissionsCitation9–11.

Approximately 65% of HF patients are 65 years and older, and HF is the leading cause of death in the Medicare population in the United StatesCitation1,Citation12,Citation13. The total direct medical cost of HF was estimated to be $31 billion in 2020 with 84% attributed to patients 65 and olderCitation13. With the rapidly aging US population, the total medical cost of HF is projected to increase to $53 billion by 2030, with the contribution of patients 65 and older projected to increase to 88% of total costsCitation13, underscoring the significantly increased burden to the Medicare program including both traditional Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) and private Medicare advantage (MA) plans. Over one-third of all Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in private MA plans, while two-thirds remain enrolled in the federally administered traditional Medicare FFS programCitation14.

Given the prevalence of HFrEF in Medicare beneficiaries and the poor prognosis of patients with chronic HFrEF following a WHFE, it is critical to understand the clinical and economic burden of chronic HFrEF following a WHFE within the growing Medicare population. Identifying areas of unmet needs among patients with and without WHFE can guide healthcare decisions, improving outcomes and reducing Medicare costs overall. The objective of this study is to compare quality outcomes, healthcare resource utilization, and costs in Medicare beneficiaries with chronic HFrEF with and without a WHFE.

Methods

Data sources

We identified eligible patients with chronic HFrEF using two different Medicare databases. First, the 100% Medicare FFS claims including part A and B medical claims and prescription drug event data for all Medicare part D plans. The FFS data includes enrollment data, demographic, mortality, and all medical/pharmacy encounters including hospital claims, emergency department (ED) visits, skilled nursing facility stays, hospital outpatient ambulatory surgical center services, physician office visits, home health services, durable medical equipment, hospice care, and all prescription drug utilization.

Second, we extracted claims for a large sample of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in private managed MA plans from Inovalon’s medical outcomes research for effectiveness and economics registry (MORE2 RegistryFootnotei). MORE2 is a real-world database inclusive of enrollment data, demographics, and medical and pharmacy encounters (including diagnoses, procedures, lab tests, and results with exact dates of service). The data are de-identified using expert statistical determination and accessed through HIPAA-compliant data use agreements with contributing MA plans. The MA data does not include mortality due to requirements of the statistical de-identification process and does not include actual payments from health plans to providers.

Study design and patient population

This retrospective observational study examined Medicare FFS and MA beneficiaries with chronic HFrEF during the study period of October 2014 to December 2018. Medicare beneficiaries were required to have continuous enrollment for a minimum of 12 months prior to the index date and 12 months post-index date in Medicare Parts A, B, and D for those enrolled in FFS and with both medical and pharmacy coverage for those enrolled in MA. The index date was defined based on the date of the earliest evidence of HFrEF within the identification period between October 2015 to September 2017. HFrEF was identified as one inpatient claim or two outpatient claims of systolic HF (ICD-10 codes: I50.20–I50.23, I50.40–I50.43), or one outpatient claim of systolic HF plus one outpatient claim of HF on two different dates during the identification period (ICD-10 codes: I11.0, I50.1, I50.2x, I50.3x, I50.4, I50.40–I50.43, I50.8x, I50.9).

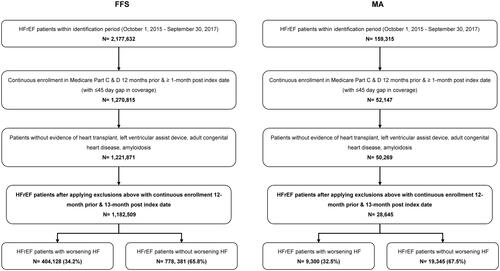

Figure 1. Consort diagram for population selection. Abbreviations. HF, Heart failure; HFrEF, Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

The baseline period was defined as the 12 months prior to the index date. Patients were excluded if there was evidence of a heart transplant procedure, left ventricular assist device, adult congenital heart disease, or amyloidosis during the baseline period. Demographic characteristics were assessed at index date and clinical variables were assessed during the baseline period. Additionally, patients with a WHFE were defined as having an HF hospitalization (i.e. HF diagnosis in the first or second position of claims) and/or IV diuretic treatment (IV diuretic use with no overnight stay in the hospital) during the one-year period after HFrEF index date (WHFE identification period). Patients without WHFE were defined as HFrEF patients who did not have a WHFE during the WHFE identification period (Supplemental Figure 1).

Outcomes were evaluated during the follow-up period which was defined as the period from the 13th month after the index date (i.e. after the end of the WHFE identification period) through the end of follow-up for each patient (i.e. time to disenrollment, end of the study period of December 2018, or date of death for Medicare FFS beneficiaries, whichever occurred first). Patients were required to have continuous enrollment for at least 1 month during the follow-up period to be included in the outcome analysis. Outcomes were reported per patient per year (PPPY) to account for varying duration of follow-up. This study did not conduct comparisons of the two Medicare populations due to multiple differences in coverage and benefits not evaluated as part of this analysis; thus, results for FFS and MA patients are presented together for reference only and are not intended for direct comparison.

Study variables

Demographic variables included age, gender, race/ethnicity, census region, dual eligibility status (patients with both Medicare and Medicaid coverage), and the original reason for Medicare entitlement (individuals aged 65 years or individuals under the age of 65 years with disability/end-stage renal disease). Clinical variables included the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), select comorbid conditions, and medication use.

Quality outcome measures including all-cause and HF-related 30-day and 90-day readmissions and patient mortality were calculated during the follow-up period. Mortality was only calculated for patients enrolled in Medicare FFS. Healthcare resource utilization measures were calculated during the baseline and follow-up periods, including all-cause and HF-related hospitalizations and length of stay, ED visits, and outpatient visits. An HF-related service was defined as a service with HF diagnosis in the primary or secondary diagnosis position on the claim. To account for differences in baseline patient characteristics, risk-adjusted utilization measures were calculated for the follow-up period.

All-cause and HF-related healthcare costs, reported as PPPY, were calculated for the baseline and follow-up periods including total cost, and cost by spending category (hospitalizations, ED visits, outpatient visits, durable medical equipment, post-acute care, and pharmacy costs). For FFS, costs were calculated using actual payments to providers. For MA, healthcare costs were calculated by applying standardized Medicare-allowed payment amounts to each type of service based on published Medicare FFS rates. Standardized pricing was applied at the National Drug Code level for each pharmacy claim using a standard discount from the average wholesale price. All costs were inflation-adjusted to 2018 prices using the Consumer Price Index medical care componentCitation15.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were evaluated using descriptive statistics. Cumulative risks of WHFE after controlling for disenrollment were calculated and plotted over the 12-month period following the index date. Differences in demographic and clinical characteristics, quality outcomes, healthcare resource utilization, and the associated costs between chronic HFrEF patients with a WHFE vs. those without WHFE were determined by chi-squared test for categorical and t-test for continuous variables. Means were calculated for continuous variables, and percentages were calculated for categorical variables. A p value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

At follow-up, quality outcomes, healthcare resource utilization, and costs were compared between patients with a WHFE vs. those without WHFE after adjusting for baseline characteristics using generalized linear models. To account for the overdispersion of count data for utilization measures, negative binomial distribution and log link function were used in the generalized linear models. The model covariates included baseline characteristics for age, gender, race, census region, dual status, chronic conditions, and hospitalizations. Models with costs as the outcome variable used gamma distribution and log-link function in the generalized linear models to fit with right-skewed cost data with a mass of zero. The cost model used the same covariates but replaced baseline hospitalization with baseline total cost.

Results

Patient population

The analysis included a total of 1,182,509 Medicare FFS and 28,645 MA beneficiaries with chronic HFrEF (). Among those, 34.2% of FFS patients and 32.5% of MA patients experienced a WHFE within 12 months after the HFrEF index date. After adjusting for the censoring event, 36.8% of FFS patients and 36.5% of MA patients experienced a WHFE within 12 months after the index date (Supplemental Figure 2).

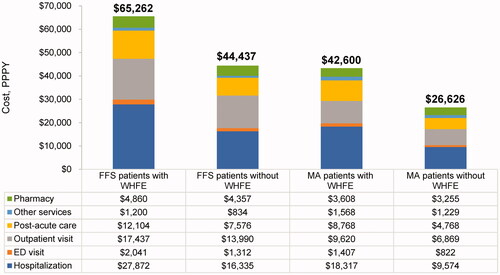

Figure 2. Adjusted all-cause cost of care during the follow-up period. Abbreviations. ED, Emergency department; FFS, Fee-for-service; MA, Medicare advantage; PPPY, Perpatient per year; WHFE, Worsening heart failure event. Costs are presented as PPPY costs in USD. The adjusted costs of care were estimated using generalized linear models with gamma distribution and log link function with covariates age, gender, race, census region, dual status, chronic conditions, and baseline total cost. p-values comparing patients with worsening HF vs. without worsening HF <0.0001 for all variables. Post-acute care setting refers to skilled nursing facilities, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, long-term acute care hospitals, or home health agencies; Other services include durable medical equipment, laboratory tests, or physician drugs.

Baseline characteristics

Compared to patients without WHFE, patients with chronic HFrEF following a WHFE were about one year older, more often female, more likely to be of Black race, and slightly more likely to be dual-eligible for Medicare and Medicaid in both FFS and MA (). Clinically, patients with WHFE had higher CCI scores on average compared to those without WHFE (FFS: 4.2 vs. 3.7; MA: 4.1 vs. 3.6). Rates of comorbidities were consistently higher among patients with WHFE compared to those without WHFE in both FFS and MA, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, type II diabetes and anemia. HF medication use, including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker (ACEI/ARB), ARNi, beta-blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRAs) was similar among patients with and without WHFE; and the use was suboptimal in both cohorts. However, patients with WHFE reported higher use of oral diuretics compared to those without WHFE (FFS: 74.3% vs. 65.4%; MA: 73.0% vs. 62.8%; ).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics, healthcare resource utilization and cost.a

Patients with chronic HFrEF following a WHFE had higher healthcare resource utilization and costs compared to those without WHFE in both FFS and MA during the baseline period. Specifically, patients with WHFE had 28% (FFS) and 62% (MA) higher all-cause hospitalization rates compared to those without WHFE (FFS: 1.25 vs. 0.98 PPPY; MA: 1.04 vs. 0.64 PPPY). All-cause total medical and pharmacy costs were 9% higher in FFS and 25% higher in MA patients with WHFE than in those without WHFE ().

Quality outcomes

During the follow-up period, mortality rates in FFS patients were higher among patients with chronic HFrEF following a WHFE (34.3%) compared to those without WHFE (23.4%; ). Rates of all-cause and HF-related 30-day readmissions were consistently higher in patients with WHFE vs. those without WHFE in both FFS (all-cause: 42% vs. 31%; HF-related: 37% vs. 27%) and MA (all-cause: 41% vs. 31%; HF-related: 32% vs. 26%). A similar pattern was observed for all-cause and HF-related 90-day readmissions for both FFS and MA.

Table 2. Adjusted healthcare resource utilization and quality outcomes during the follow-up period.a

The differences in readmission rates between patients with and without WHFE were persistent even after adjusting for patient characteristics. After adjusting for patient characteristics, all-cause and HF-related 30-day readmissions in FFS were, respectively, 2.0 times (0.71 vs. 0.36 PPPY) and 3.1 times (0.29 vs. 0.09 PPPY) higher in patients with WHFE compared to those without WHFE (). A similar pattern was observed in MA patients, where all-cause and HF-related 30-day readmissions were, respectively, 2.2 times (0.77 vs. 0.35 PPPY) and 5.2 times (0.29 vs. 0.05 PPPY) higher in the patients with WHFE compared to those without WHFE (). Unadjusted rates of quality outcomes are presented in Supplemental Table 1.

Healthcare resource utilization

All-cause and HF-related hospitalizations, ED visits, and outpatient visits were consistently higher among patients with chronic HFrEF following a WHFE compared to those without WHFE in both FFS and MA. These results were consistent even after adjusting for patient characteristics. Specifically, among FFS patients with WHFE, adjusted all-cause and HF-related hospitalization rates were, respectively, 1.7 times (2.27 vs. 1.36 PPPY) and 2.5 times (0.82 vs. 0.33 PPPY) higher compared to patients without WHFE (). Among MA patients with WHFE, adjusted all-cause hospitalization rates were 1.9 times higher (1.47 vs. 0.78 PPPY) and HF-related hospitalization rates were 3.4 times higher (0.51 vs. 0.15 PPPY). Similar findings were observed for ER and outpatient visits in both FFS and MA (). Unadjusted rates for healthcare resource utilization are presented in Supplemental Table 1.

Healthcare costs

Healthcare costs were higher in patients with WHFE than in those without WHFE, and the results were consistent after adjusting for confounding factors. Compared to patients without WHFE, patients with WHFE incurred $20,825 (FFS) and $15,974 (MA) higher adjusted total healthcare costs (FFS: $65,262 vs. $44,437 PPPY; MA: $42,600 vs. $26,626 PPPY; ). Hospitalizations were the main driver of total costs, with the similar average cost per stay in patients with and without WHFE (FFS: $12,041 vs. $12,366; MA: $11,139 vs. $11,558).

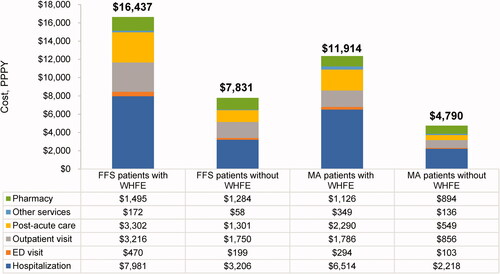

Similar to overall healthcare costs, HF-related costs were consistently higher in patients with WHFE than in those without WHFE. Adjusted total HF-related healthcare costs were $8,606 (FFS) and $7,124 (MA) higher in patients with WHFE compared to those without WHFE (FFS: $16,437 vs. $7,831 PPPY; MA: $11,914 vs. $4,790 PPPY; ) adjusted costs for HF-related hospitalizations were $4,775 higher in FFS and $4,296 higher in MA) for patients with WHFE than for those without WHFE (FFS: $7,981 vs. $3,206 PPPY; MA: $6,514 vs. $2,218 PPPY).

Figure 3. Adjusted heart failure-related cost of care during the follow-up period. Abbreviations. ED, Emergency department; FFS, Fee-for-service; MA, Medicare advantage; PPPY, Per patient per year; WHFE, Worsening heart failure event. Costs are presented as PPPY costs in USD. The adjusted costs of care were estimated using generalized linear models with gamma distribution and log link function with covariates age, gender, race, census region, dual status, chronic conditions, and baseline total cost. p-values comparing patients with worsening HF vs. without worsening HF <0.0001 for all variables. Post-acute care setting refers to skilled nursing facilities, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, long-term acute care hospitals, or home health agencies; Other services include durable medical equipment, laboratory tests, or physician drugs.

Discussion

HFrEF represents an important public health issue that will continue to increase as the population ages. This retrospective observational study compared patient characteristics and outcomes among patients with chronic HFrEF following a WHFE to those without WHFE in two distinct populations of Medicare beneficiaries, those in traditional Medicare FFS and those in private MA plans. MA plans are private managed health plans (primarily Health Maintenance Organizations and Preferred Providers Organizations) that provide medical benefits for Medicare beneficiaries as an alternative to the federally administered traditional Medicare FFS programCitation16. MA plans are important to evaluate due to their rapid growth as a proportion of the Medicare population, now representing more than one-third of all Medicare beneficiariesCitation14. In contrast to FFS claims data that have been studied for decades, MA data has not been available; thus, until now, little has been known about this rapidly growing component of Medicare. Since the majority of patients with HFrEF are aged 65 and above, examining HFrEF patients from 100% of Medicare FFS claims and a large representative sample of MA plans provides a comprehensive profile of patients with chronic HFrEF to better inform healthcare decision making.

In this study, approximately one-third of Medicare patients with chronic HFrEF experienced a WHFE within 12 months of their HFrEF index date diagnosis within the WHFE identification period. This is higher than the 27% of commercially insured HFrEF patients under the age of 65 years who developed WHFE within 12 months of the HFrEF index date reported by Butler et al. (2020)Citation4. The higher rates of WHFE in this study—34% in FFS and 33% in MA—could be due to Medicare beneficiaries being older on average with more comorbiditiesCitation3,Citation4. Adjusted HF-related hospitalizations were similarly 2.5 times higher in FFS and 3.4 times higher in MA patients with chronic HFrEF following a WHFE compared to those without WHFE. These results are consistent with several previously published studies demonstrating the disease burden in patients who develop worsening heart failureCitation3,Citation4,Citation17,Citation18. Adjusted total costs and spending within categories were also higher among patients with chronic HFrEF following a WHFE compared to those without WHFE. Higher healthcare resource utilization and costs in patients with chronic HFrEF following a WHFE compared to those without WHFE is consistent with results reported by Butler et al. (2020) in a commercially insured patient populationCitation4.

Quality outcomes evaluated using Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services quality measures were also higher in patients with chronic HFrEF following a WHFE compared to those without WHFE. These results were consistent after adjusting for patient baseline characteristics. There were high rates of mortality in the FFS population; 34.3% among patients with chronic HFrEF experiencing a WHFE compared to 23.4% among patients who did not experience WHFE. Rates of all-cause 30-day readmissions were 31% higher in FFS and 32% higher in MA in patients with WHFE compared to those without WHFE. All-cause 30-day readmissions are a key focus area for MA plans as it is a triple-weighted quality measure in the five-star rating system used in public reporting and to determine bonus paymentsCitation19. Similarly, FFS providers are subject to value-based purchasing programs such as the Medicare Shared Savings Program that include readmissions as a key measure, and hospitals serving Medicare patients are subject to penalties for higher-than-expected readmissionsCitation11. Therefore, these findings highlight the importance of addressing these poor outcomes in patients with chronic HFrEf following a WHFE.

While the study objectives were not intended to compare outcomes between the FFS and MA populations, similar trends between patients with chronic HFrEF following a WHFE and those without WHFE were observed in quality outcomes, healthcare utilization, and costs among FFS and MA beneficiaries. However, there were also some differences in outcomes between MA and FFS beneficiaries to note. For example, HF-related hospitalization rates were 0.82 PPPY for FFS patients and 0.51 PPPY for MA patients with WHFE. These differences between MA and FFS could be due to multiple factors related to how the traditional FFS program operates in practice compared to managed MA plans (e.g. beneficiaries enrolled in MA plans tend to receive better-coordinated care and more preventative services than those in FFS), as well as differences in characteristics of beneficiaries who select FFS vs. MACitation10. In addition, mortality data is not available in MA (it is only available in Medicare FFS), and the lack of mortality data may impact some outcomes reported here. However, evaluating which factors contributed to the differences observed between FFS and MA plans was not the objective of this study.

Limitations

Despite the importance of the present findings, there are limitations to this study. First, the primary data source includes only Medicare FFS beneficiaries and MA patients and may not be generalizable to patients without insurance coverage or other coverage types, such as managed Medicaid or commercial insurance plans. Furthermore, the results presented here may not be generalizable to individuals outside of the United States. Second, there are limitations of using administrative claims to ascertain HFrEF. Billing diagnosis codes specific for reduced-ejection fraction may underestimate or overestimate the number of patients with chronic HFrEF because ejection-fraction level is not available. In addition, there are no data on implantable cardioverter-defibrillator and implantable cardiac resynchronization therapy. Finally, as a retrospective study design, results cannot be used to determine cause and effect, as claims data only capture those disease entities and variables with their own specific billing codes. Some diagnoses and medication use may not be consistently documented or captured in claims data.

Conclusions

In this study, one-third of Medicare beneficiaries with chronic HFrEF experienced worsening HF within 12 months of diagnosis, and 34.3% died during the follow-up period. Despite improvements in care, quality outcomes (i.e. mortality and readmissions), healthcare resource utilization, and costs of care were higher in patients with chronic HFrEF following a WHFE compared to those who did not experience a WHFE, even after adjusting for baseline patient characteristics. Overall differences in outcomes indicate substantial unmet needs among Medicare beneficiaries with chronic HFrEF experiencing WHFE, underscoring the need for better treatments and innovative approaches to improve clinical and economic outcomes in the vulnerable and fast-growing Medicare population.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The study was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

Declaration of financial/other interests

R.J. Mentz reports grants and personal fees from Merck, grants and personal fees from Bayer, during the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from Novartis, from Amgen, grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from BI, outside the submitted work; and RJM received research support and honoraria from Abbott, American Regent, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim/Eli Lilly, Boston Scientific, Cytokinetics, Fast BioMedical, Gilead, Innolife, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis, Relypsa, Respicardia, Roche, Sanofi, Vifor, and Windtree Therapeutics.

Z. Pulungan has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

S. Kim has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

C. Teigland has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

L.M. Djatche and R. Hilkert are employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA, and are shareholders of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

M. Yang was an employee of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA, at the time of the study.

JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work, but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

L.M. Djatche, M. Yang, C. Teigland, Z. Pulungan and R.J. Mentz made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study. Data acquisition and analysis were conducted by Z. Pulungan and S. Kim. All authors contributed to data interpretation and approve the final version of the published manuscript. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (197 KB)Acknowledgements

Barnabie Agatep and Anny Wong of Avalere Health provided research and project management support for this study, which was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA

Data availability statement

Eligible patients were selected using two different de-identified Medicare databases: 1) the 100% Medicare fee-for-service claims including part A and B medical claims and prescription drug event data for all Medicare part D plans and 2) Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in private managed Medicare advantage plans data from Inovalon’s medical outcomes research for effectiveness and economics registry (MORE2 Registry).

Notes

i MORE2 Registry is a registered trademark of Inovalon, Bowie, MD, USA.

References

- Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2020 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141(9):e139–e596.

- Fitch K, Lau J, Engel T, et al. The cost impact to Medicare of shifting treatment of worsening heart failure from inpatient to outpatient management settings. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;10:855–863.

- Butler J, Yang M, Manzi MA, et al. Clinical course of patients with worsening heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(8):935–944.

- Butler J, Djatche LM, Sawhney B, et al. Clinical and economic burden of chronic heart failure and reduced ejection fraction following a worsening heart failure event. Adv Ther. 2020;37(9):4015–4032.

- Ambrosy AP, Fonarow GC, Butler J, et al. The global health and economic burden of hospitalizations for heart failure: lessons learned from hospitalized heart failure registries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(12):1123–1133.

- Okumura N, Jhund PS, Gong J, et al. Importance of clinical worsening of heart failure treated in the outpatient setting: evidence from the prospective comparison of ARNI with ACEI to determine impact on global mortality and morbidity in heart failure trial (PARADIGM-HF). Circulation. 2016;133(23):2254–2262.

- Rame JE, Sheffield MA, Dries DL, et al. Outcomes after emergency department discharge with a primary diagnosis of heart failure. Am Heart J. 2001;142(4):714–719.

- DeVore AD, Hammill BG, Sharma PP, et al. In-hospital worsening heart failure and associations with mortality, readmission, and healthcare utilization. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(4):e001088.

- America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP) Center for Policy and Research. Innovations in Reducing Preventable Hospital Admissions, Readmissions, and Emergency Room Use. 2010. Available from: http://docshare01.docshare.tips/files/26469/264694950.pdf

- Teigland C, Pulungan Z, Shah T, et al. As it grows, medicare advantage is enrolling more low-income and medically complex beneficiaries. The Commonwealth Fund. 2020.

- CMS. Medicare shared savings program: Accountable Care Organization (ACO) 2018. quality measures. Published online 2018 [cited 2020 October 29]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/Downloads/2018-reporting-year-narrative-specifications.pdf

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2–e220.

- Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, et al. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(3):606–619.

- Jacobson G, Freed M, Damico AA. Dozen facts about Medicare advantage in 2019 Published 2019 June 6 [cited 2020 October 9]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/a-dozen-facts-about-medicare-advantage-in-2019/

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. How BLS measures price change for medical care services in the consumer price index [cited 2020 August 28]. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/cpi/factsheets/medical-care.htm#A2

- CMS. Health plans – general information [cited 2020 October 15]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/HealthPlansGenInfo

- Allen LA, Smoyer Tomic KE, Wilson KL, et al. The inpatient experience and predictors of length of stay for patients hospitalized with systolic heart failure: comparison by commercial, Medicaid, and Medicare payer type. J Med Econ. 2013;16(1):43–54.

- Allen LA, Smoyer Tomic KE, Smith DM, et al. Rates and predictors of 30-day readmission among commercially insured and Medicaid-enrolled patients hospitalized with systolic heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5(6):672–679.

- CMS. Medicare 2020 Part C & D star ratings technical notes. Published online 2019. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovGenIn/Downloads/Star-Ratings-Technical-Notes-Oct-10-2019.pdf