Abstract

Background

Real-world evidence on atypical antipsychotic (AAP) use in pediatric bipolar disorder is limited.

Objective

To assess the risk of all-cause and psychiatric hospitalization among pediatric patients with bipolar disorder when treated with lurasidone versus other atypical antipsychotics (AAPs).

Methods

This retrospective cohort study used commercial claims data (January 1, 2011 to June 30, 2017) to identify pediatric patients (age ≤17 years) with bipolar disorder treated with oral atypical antipsychotics (N = 16,201). The date of the first claim for an AAP defined the index date, with pre- and post-index periods of 180 days. Each month of the post-index period was categorized as monotherapy treatment with lurasidone, aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, or risperidone, no/minimal treatment, or other. The risk of all-cause and psychiatric hospitalizations (defined by a psychiatric diagnosis on the facility claim) was analyzed based on treatment in the current month, time-varying covariates (prior treatment-month classification, hospitalization in the prior month, emergency room visit in the prior month), and fixed covariates (age, gender, pervasive development disorder/mental retardation, disruptive behavior/conduct disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, depression, anxiety, adjustment disorder, obesity, diabetes, antidepressants, anxiolytics, other co-medication) using a marginal structural model.

Results

Treatment with aripiprazole (OR = 1.60, 95% CI: 1.08–2.36) and olanzapine (OR = 1.68, CI: 1.03–2.71) was associated with significantly higher odds of all-cause hospitalizations compared to lurasidone, but treatment with quetiapine (OR = 1.03, CI: 0.69–1.54) or risperidone (OR = 1.02, CI: 0.68–1.53) was not. Similarly, treatment with aripiprazole (OR = 1.61, 95% CI: 1.08–2.38) and olanzapine (OR = 1.73, CI: 1.06–2.80) was associated with significantly higher odds of psychiatric hospitalizations compared to lurasidone, but treatment with quetiapine (OR = 1.02, CI: 0.68–1.54) or risperidone (OR = 1.01, CI: 0.67–1.51) was not.

Conclusion

In usual clinical care, pediatric patients with bipolar disorder treated with lurasidone had a significantly lower risk of all-cause and psychiatric hospitalizations when compared to aripiprazole and olanzapine, but not quetiapine or risperidone.

Introduction

Bipolar disorder is a chronic and debilitating psychiatric disorder with lifetime prevalence estimates in the US ranging from 3.9% to 4.4%Citation1,Citation2. Among children and adolescents, the prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorders is estimated at 3.9%Citation3. Patients with bipolar disorder experience episodes of mania or depression and interludes of no symptomsCitation4, with depressive episodes accounting for approximately two-thirds of symptomatic timeCitation5.

Pediatric bipolar disorder is associated with functional impairment, along with high rates of comorbid psychiatric and medical problemsCitation6. Perhaps of most concern is the increased risk of suicide for children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted among juveniles with bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder reported suicide attempt rates of 31.5% for bipolar disorder and 20.5% for the major depressive disorderCitation7. The risk of suicide attempts was found to be 1.7-times greater for bipolar disorder versus major depressive disorder. The rates of suicide attempts for patients with a current diagnosis of hypomania or mania without major depression were lower than for those for patients diagnosed with the major depressive disorderCitation7. In addition to the emotional cost of self-harm and suicidal ideation, there is an increased burden on healthcare resource utilization. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts have been found to account for 1.2% of all child and adolescent emergency department visits between 2010 and 2014Citation8. Bipolar disorder in particular is associated with substantial healthcare costs, which are largely driven by hospitalizations and emergency room visitsCitation9–11.

The Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT)/International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) guidelines include recommendations regarding the treatment of pediatric bipolar disorderCitation12. For the acute management of pediatric bipolar depression, lurasidone is recommended as a first-line treatment. Lithium and lamotrigine are recommended as second-line agents and olanzapine-fluoxetine combination and quetiapine are recommended as third-line options. Lithium, risperidone, aripiprazole, asenapine, quetiapine, olanzapine, ziprasidone, and Divalproex are included in the recommendations for the treatment of pediatric bipolar mania. Currently, only two second-generation antipsychotic medications are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of major depressive episodes associated with bipolar disorder in children and adolescents: olanzapine/fluoxetine combination and lurasidoneCitation13,Citation14. The efficacy of the olanzapine/fluoxetine combination was established in an 8-week placebo-controlled trial of 255 patients (age 10–17) that found significantly larger reductions on the Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised (−28.4 vs −23.4, p = .003) for patients treated with olanzapine/fluoxetineCitation15. The efficacy of lurasidone for the treatment of children and adolescents with acute bipolar depression was established in a 6-week randomized placebo-controlled trial of 347 patients (age 10–17) that found significantly larger reductions on the Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised (−21.0 vs −15.3, p < .0001) for patients treated with lurasidoneCitation15. For further details of treatment issues in pediatric disorder, including an overview of other placebo-controlled trials the interested reader is referred to treatment guidelines and recent review papersCitation12,Citation16,Citation17.

To date, there have been no head-to-head studies comparing outcomes for atypical antipsychotics in pediatric bipolar disorder. In addition, no studies have examined hospitalization rates between lurasidone and other atypical antipsychotics in pediatric bipolar disorder. Thus, a real-world evaluation of hospitalization rates and outcomes associated with different atypical antipsychotics may serve to inform clinical and formulary decision-making. The purpose of this retrospective observational study was to evaluate the risk of all-cause and psychiatric hospitalization among pediatric patients with bipolar disorder when treated with lurasidone versus other atypical antipsychotics.

Methods

Study design, methods, and database

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using commercial claims data from the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database, which is representative of the US population with employer-provided health insurance. The study used claims data from January 1, 2011 to June 30, 2017. The analysis consisted of de-identified data that was extracted via processes compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996Citation18. Therefore, institutional review board approval was not required.

Patient inclusion/exclusion criteria

Patients were included in the study if they initiated one of the following oral atypical antipsychotics: lurasidone, quetiapine, risperidone, aripiprazole, or olanzapine between July 1, 2011 and December 31, 2016. Lurasidone patients were selected first to maximize cohort size. The date of the first claim for the atypical antipsychotic was identified as the index date and the atypical antipsychotic filled on the index date was designated as the index atypical antipsychotic.

Patients were children and adolescents (age ≤17 years) who had continuous health plan enrollment for a minimum of 6 months pre- index (baseline period) and 6 months post-index date, and no claims for any use of typical or atypical antipsychotics during the pre-index period or more than 1 antipsychotic on the index date. Patients were required to have at least 1 primary diagnosis of bipolar disorder on the index date or during the 6-month pre-index period. Bipolar disorder diagnoses were determined using ICD-9/10-CM diagnoses codes from medical claims (ICD-9-CM: 296.0, 296.1, 296.4–296.9; ICD-10-CM: F30, F31)

Treatment categorization

The primary unit of analysis was treatment months. To control for temporal effects of switching and concomitant therapy, the 180-day post period was divided into six 30-day intervals (“months”). Patients were assigned to one of the seven mutually exclusive treatment categories each month. Five of the 7 treatment categories were lurasidone, aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, or risperidone monotherapy. Monotherapy treatment was operationally defined as ≥22 days of an atypical antipsychotic during the 30-day interval (over 75%) with no treatment with other atypical antipsychotics, or lithium or valproate. The 5 atypical antipsychotic monotherapies were the primary treatments of interest. The remaining two treatment categories were categorized as either no/minimal treatment or other treatment. The no/minimal treatment category was defined as either no treatment with an atypical antipsychotic or ≤7 days of treatment with the atypical antipsychotics of interest. The other treatment category was heterogeneous and defined as the use of multiple oral atypical antipsychotics, use of any of the antipsychotics of interest for 8–21 days, or use of a single antipsychotic combined with lithium or valproate. The no/minimal and other treatment categories were included for statistical modeling purposes.

Outcome variable definitions

The primary outcome variable was a binary indicator of all-cause hospitalization, defined as any inpatient hospital stay. A secondary outcome variable was a binary indicator of psychiatric hospitalization in each post-index month. Psychiatric hospitalization was defined as hospitalization with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, adjustment disorder, anxiety disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), communication and learning disorders, depression, disruptive behavior/conduct disorder, and other mental disorders in any position on the facility claim.

Adherence rates

As the unit of analysis in this study was the treatment-month rather than patient, commonly used measures of adherence, such as medication possession ratio or proportion of days covered, were not appropriate. Adherence was measured descriptively using a method developed specifically for the design of this studyCitation19. Adherence was conceptualized as possessing monotherapy antipsychotic treatment for at least 22 days of a treatment month (≥75%). Each treatment month with ≥22 days of antipsychotic monotherapy treatment was coded as adherent and assigned a value of 1, and treatment months of no/minimal or other treatment were coded as non-adherent and assigned a value of 0. When a patient switched to a new antipsychotic, the adherence calculation reset and was attributed to the new antipsychotic unless a switch to another antipsychotic occurred or the end of the study period was reached. The final determination of adherence was weighted by the number of months for the treatment. Adherence could range from 0 to 1, with 1 representing full adherence.

Demographics, comorbidities, and healthcare resource utilization during the pre-index period

Patient characteristics were coded to describe the patient population or to control for patient and treatment-month differences in the models. Demographics (age and gender) and baseline clinical characteristics, such as co-medications (antidepressants, anxiolytics, stimulants, mood stabilizers, and α2-agonists) and clinical comorbidities were compared between the lurasidone and other atypical antipsychotic cohorts.

All-cause healthcare resource use did not have diagnostic restrictions and thus was inclusive of psychiatric-related care. Pre-index psychiatric-related healthcare resource utilization was identified using at least one relevant diagnostic code. Psychiatric-related use code could be in any position on the associated claim.

Statistical methods

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics were descriptively compared using numbers and percentages for categorical variables and means and standard deviations for continuous variables. The lurasidone cohort was compared to each of the other first-month treatment cohorts using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. A generalized linear mixed model for repeated measures with a compound symmetry covariance structure was used to compare adherence rates between lurasidone and other atypical antipsychotics.

The unadjusted all-cause and psychiatric hospitalization rates per 100 patient months were reported. In addition, marginal structural models were used to examine the effects of atypical antipsychotic treatment on hospitalizations. Marginal structural models can be used to estimate causal treatment effects in cases where treatment and other covariates change over timeCitation20. This is achieved by weighting the data with the probability of receiving each of the treatments in each treatment period using stabilized inverse propensity of treatment weighting. Specified time-dependent confounding variables can be controlled for when the outcomes of interest are modeledCitation21. Stabilized inverse probability weights were calculated for each patient month in the post-index period. A multinomial logistic regression model was used to predict assignment to each treatment category using pre-index (fixed) and post-index (time-varying) covariates. The fixed covariates included age, gender, pervasive development disorder/mental retardation, disruptive behavior/conduct disorder, ADHD, depression, anxiety, adjustment disorder, obesity, diabetes, antidepressants, anxiolytics, other co-medication (stimulants, mood stabilizers, α2-agonists). The time-varying covariates included prior treatment-month classification, hospitalization in the prior month, emergency room visits in the prior month. Because there was no pre-index antipsychotic treatment, stabilized inverse probability weights could not be calculated for month 1; therefore, outcomes were modeled over month 2 through month 6. The counts of hospitalization were modeled using generalized estimating equations with an autoregressive correlation matrix, binomial distribution, and logit link function, and were reported as odds ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals. The generalized estimating equation models were weighted using the stabilized inverse propensity of treatment weightings. SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used to complete all analyses with an alpha level set at p < .05.

Results

Patient characteristics

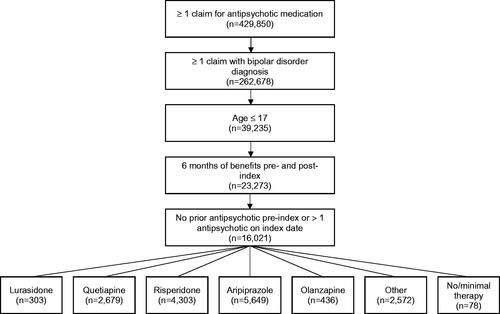

A total of 16,201 children or adolescents with bipolar disorder met all the inclusion/exclusion criteria. shows the patient flow through selection criteria. At month 1 of the study period, the number of patients assigned to the various atypical anti-psychotic treatment groups was: lurasidone (n = 303), quetiapine (n = 2,679), risperidone (n = 4,303), aripiprazole (n = 5,649), olanzapine (n = 436), other treatment (n = 2,572), and no/minimal antipsychotic treatment (n = 78).

Pre-index patient characteristics at month 1 of the study period by initial treatment are shown in . The average age among all patients was 13.8 years and nearly half (49%) were female. The lurasidone cohort had a significantly higher proportion of adolescent patients (aged 13–17 years) compared to other cohorts (92.4% vs 54.4–87.8%, p < .01). In addition, patients prescribed lurasidone in month 1 had a significantly higher proportion of anxiolytic use (18.2% vs 4.7–10.1%; p < .005) and other medication use (61.7% vs 39.5–51.3%; p < .001) compared to other cohorts. The lurasidone cohort also had a higher proportion of antidepressant use (52.1% vs 39.7%; p < .001) compared to the risperidone cohort. On average, patients who have prescribed lurasidone in month 1 had significantly fewer psychiatric inpatient admissions compared to patients prescribed quetiapine and olanzapine (0.50, 0.65, and 0.64, respectively; p < .05). The most common comorbidities observed across all cohorts were depression or unspecified mood disorder, ADHD, and conduct disorder (46%, 39%, and 27%, respectively).

Table 1. Pre-index patient demographics, comorbidities, and healthcare utilization by treatment group at month 1.

Adherence rates

shows the number of patients in each treatment group over time. Lurasidone-treated patients had a mean weighted adherence of 0.52. Which was significantly higher than quetiapine (0.46; p < .001), risperidone (0.39; p = .006), and aripiprazole (0.49; p = .010), but not olanzapine (0.53; p < .001).

Table 2. Number of patients in each treatment group by month.

Hospitalization rates during the 6-month follow-up period

The observed rates of all-cause and psychiatric hospitalizations during months 2–6 stratified by the prior month’s treatment are shown in . The unadjusted all-cause hospitalization rates per 100 patient months were 4.3 for lurasidone, 5.2 for quetiapine (p = .307 vs lurasidone), 3.6 for risperidone (p = .287), 6.8 for aripiprazole (p = .008), and 8.4 for olanzapine (p = .001). Treatment with aripiprazole or olanzapine was associated with a significantly higher rate of all-cause hospitalizations in the post-index period versus lurasidone. The vast majority (98%) of the 2,257 all-cause hospitalizations were psychiatric hospitalizations (n = 2,211). Thus, the unadjusted psychiatric hospitalization rates were very similar to but slightly lower than the all-cause hospitalization rates. The unadjusted psychiatric hospitalization rates per 100 patient months were 4.2 for lurasidone, 5.1 for quetiapine (p = .307 vs lurasidone), 3.5 for risperidone (p = .286), 6.7 for aripiprazole (p = .007), and 8.2 for olanzapine (p = .001). Treatment with lurasidone was associated with a significantly lower rate of psychiatric hospitalizations in the post-index period versus aripiprazole and olanzapine.

Table 3. Unadjusted rates of psychiatric and all-cause hospitalizations by antipsychotic treatment.

Marginal structural model

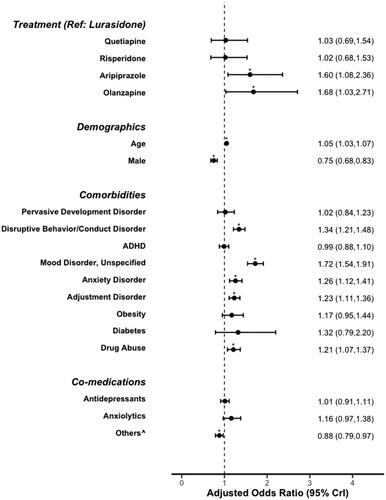

The odds of an all-cause hospitalization for each treatment group versus lurasidone are shown in . After applying inverse probability weights and statistically controlling for pre-index covariates, treatment with aripiprazole or olanzapine was associated with significantly higher odds of all-cause hospitalizations when compared to lurasidone. Psychiatric comorbidities (disruptive/conduct disorder, unspecified mood disorder, anxiety disorder, adjustment disorder) and substance abuse were associated with significantly increased odds of hospitalization while being male and use of a stimulant, mood stabilizer or α2-agonist at baseline was associated with significantly decreased odds of hospitalization ().

Figure 2. All-cause hospitalizations during the 6-month follow-up period from the marginal structural model. ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval. ^Includes stimulants, mood stabilizers, or α2-agonists.

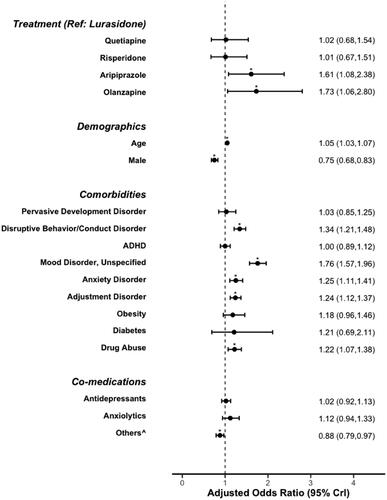

The odds of psychiatric hospitalization for each treatment group versus lurasidone are shown in . After applying inverse probability weights and statistically controlling for pre-index covariates, aripiprazole and olanzapine treatment had statistically significantly higher odds of psychiatric hospitalization than lurasidone. Similar to all-cause hospitalization risk, the presence of psychiatric comorbidities and substance abuse were associated with significantly increased odds of hospitalization, and male gender and stimulant, mood stabilizer, or α2-agonist use were associated with significantly decreased odds of hospitalization ().

Discussion

To date, no studies have examined hospitalization rates between lurasidone-treated patients compared with other atypical antipsychotics for pediatric bipolar disorder in a real-world setting. This retrospective, comparative, claims database analysis found that relative to lurasidone-treated patients, aripiprazole- and olanzapine-treated patients had 61–73% higher odds of all-cause hospitalization. All-cause hospitalization risk was not significantly different for quetiapine- or risperidone-treated patients than lurasidone-treated patients. As expected, the findings regarding the risk of psychiatric hospitalizations were similar as the vast majority of all-cause hospitalizations in this study were psychiatric. A psychiatric hospitalization generally reflects a poor clinical outcomeCitation22, where a patient may have become a danger to themselves or othersCitation23, and an important economic burden to the healthcare systemCitation9,Citation24.

The findings in this study were consistent with those in a similarly designed study among adults with the bipolar study. Ng-Mak and colleagues reported a lower risk of psychiatric hospitalization for lurasidone-treated patients when compared to aripiprazole-, olanzapine-, quetiapine-, and risperidone-treated patientsCitation19. In addition, adherence rates were significantly higher for lurasidone when compared to the other treatments.

A recent systematic review of medication adherence in pediatric patients with bipolar disorder only found 6 published studies and only 3 published studies that included antipsychoticsCitation25. Full adherence rates reported in the review ranged from 34% to 68%, but there was high variability in study designs, populations, and statistical methodsCitation25. The adherence rates found in this study (39–53%) are consistent with this range, but not directly comparable to any of the prior studies due to the differences in study designs and measures of adherence.

Minimizing the risk of hospitalizations in pediatric bipolar disorder is an important treatment goal. Hospitalizations for serious mental illness are associated with poor patient outcomesCitation26,Citation27. In addition, bipolar disorder is associated with substantial healthcare costs. In 2015, direct costs for bipolar I disorder in the US were estimated at nearly 47 billion dollars, with hospitalizations and emergency room visits accounting for over one-third of the costsCitation9. Few studies have assessed the cost of bipolar disorder in children. One study in children with bipolar disorder reported mental health services comprised 71% of total health care costs, with hospitalizations accounting for the largest portion of spendingCitation10. Another study using behavioral health insurance claims from approximately 1.7 million individuals found that while only 3.0% were identified as having bipolar disorder, they accounted for 12.4% of the total plan expendituresCitation11. Furthermore, the high rate of suicide attempts in pediatric bipolar disorder is likely to add to the number of hospitalizations in cases where they have become a danger to themselves or othersCitation7,Citation23,Citation28. The findings as we report here, that are based on comparative, real-world analyses, may help inform clinicians and formulary decision-makers to help reduce the number of pediatric bipolar hospital admissions.

In addition to evaluating the effect of treatment on outcomes, this study also identified risk factors for hospitalization. Patients with comorbid psychiatric conditions, such as disruptive/conduct disorder, unspecified mood disorder, anxiety disorder, and adjustment disorder, and substance abuse were at increased risk of hospitalization. Many of these comorbidities are common in pediatric bipolar disorder and associated with poor clinical outcomes beyond the increased risk of hospitalization. A systematic review examining the prevalence and clinical impact of comorbidities in pediatric bipolar disorder found the most prevalent were anxiety disorders (54%), ADHD (48%), disruptive behavioral disorder (31%), and substance use disorder (31%)Citation29. These comorbidities were found to be associated with poorer recovery and greater number of mood episodes after the first hospitalization, and greater functional impairment.

A strength of this study is the use of marginal structural modeling. Patients with bipolar disorder frequently switch between treatments and treatment changes are often related to emergency room visits or hospitalizations that occur during follow-up. Observational studies using an intent to treat approach in this population are challenging as they cannot estimate the effect of change in treatment on outcomes. The estimation of causal effects of treatment is considered to be improved by using a structural model that assessed treatment in each month and adjusted for known and measured time-sensitive confounding variablesCitation30.

Limitations

Results from this administrative claims-based study are subject to the limitations of the underlying data including potential miscoding and missing information. While administrative claims are excellent measures of hospitalization and other healthcare service use, the diagnoses were made for billing purposes and may not be as robust as diagnoses in clinical research. While the marginal structural models adjusted for multiple pre- and post-index covariates, it is possible that residual confounding remains due to important, but unavailable patient characteristics (i.e. symptom severity, duration of illness, race, etc.). The potential for residual confounding based on clinical characteristics that were not available represents the largest threat to the validity of this study. The ultimate cause of the hospitalizations cannot be determined from the administrative data and patients may have changed treatment or not filled prescriptions before being hospitalized. The risk estimates in this study were based on the prescription fill information during a month and the proximity in time to a claim for a hospitalization. Finally, the study only included pediatric bipolar disorder patients covered by employer-provided commercial insurance only and may not be generalizable to patients with other types of insurance, or uninsured patients.

Conclusions

In this retrospective claims database study, lurasidone treatment was associated with a significantly lower risk of all-cause and psychiatric hospitalization compared to treatment with aripiprazole and olanzapine over a 6-month follow-up period. Treatment with lurasidone was also associated with significantly better adherence compared to quetiapine, risperidone, and aripiprazole. These findings suggest that lurasidone may be a beneficial treatment option for pediatric patients with bipolar depression.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Declarations of financial/other interests

AK, CDembek, and RW are full-time employees of Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc the sponsor of the study and manufacturer of lurasidone (brand name Latuda). The peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work. In addition, a reviewer on this manuscript has received manuscript or speaker’s fees from Astellas, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Elsevier Japan, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Kyowa Yakuhin, Lundbeck, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Nihon Medi-Physics, Novartis, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Shionogi, Shire, Tsumura, Wiley Japan, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin and research grants from Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Eisai, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, and Shionogi. The reviewers have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Authors' contributions

AK, CDembek, and RW made substantial contributions to the design of the study, the interpretation of the data and have substantially revised the work. YL and CDieyi made substantial contributions to the design of the study, the data analysis, the interpretation of the data, and have substantially revised the work. All authors have approved the final submitted version of the manuscripts and agree to be both personally accountable for their contributions and ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work will be appropriately investigated, resolved, and documented in the literature.

Previous presentations

Some of these were previously presented in poster form at the US Psychiatry and Mental Health Congress held in San Diego in 2019: Ng-Mak, Kadakia A, Shrestha et al. Hospitalization risk in pediatric bipolar patients treated with lurasidone vs. other oral atypical antipsychotics: A real-world retrospective claims database study presented at 32nd US Psychiatry and Mental Health Congress (USPsych) Oct 3–6, 2019; San Diego.

Acknowledgements

We thank Michael Stensland of Agile Outcomes Research Inc and Thomas Lee of Pandion Communications Inc, who provided technical writing services on behalf of Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc.

References

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602.

- Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):543–552.

- Van Meter A, Moreira ALR, Youngstrom E. Updated meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies of pediatric bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80:18–r12180.

- American Psychiatric Association, editor. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Miller S, Dell'Osso B, Ketter TA. The prevalence and burden of bipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2014;169:S3–S11.

- Goldstein BI. Recent progress in understanding pediatric bipolar disorder. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(4):362–371.

- De Crescenzo F, Serra G, Maisto F, et al. Suicide attempts in juvenile bipolar versus major depressive disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(10):825–831.e3.

- Carbone JT, Holzer KJ, Vaughn MG. Child and adolescent suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: evidence from the healthcare cost and utilization project. J Pediatr. 2019;206:225–231.

- Cloutier M, Greene M, Guerin A, et al. The economic burden of bipolar I disorder in the United States in 2015. J Affect Disord. 2018;226:45–51.

- Dusetzina SB, Farley JF, Weinberger M, et al. Treatment use and costs among privately insured youths with diagnoses of bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(10):1019–1025.

- Peele PB, Xu Y, Kupfer DJ. Insurance expenditures on bipolar disorder: clinical and parity implications. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(7):1286–1290.

- Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) and international society for bipolar disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97–170.

- Eli Lilly and Company. Zyprexa (olanzapine) tablets prescribing information [Internet]. U.S. Food & Drug Administration; 2018. [cited 2019 Jun 6]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/020592s071,021086s046,021253s059lbl.pdf

- Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc. Latuda (lurasidone hydrochloride) tablets prescribing information. U.S. Food & Drug Administration; 2018. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/200603s029lbl.pdf

- DelBello MP, Goldman R, Phillips D, et al. Efficacy and safety of lurasidone in children and adolescents with bipolar I depression: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(12):1015–1025.

- Post RM, Grunze H. The challenges of children with bipolar disorder. Medicina. 2021;57(6):601.

- Findling RL, Chang KD. Improving the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(2):62–69.

- United States Congress. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. 104–191 [cited 1996 Aug 21]. Available from: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-104publ191/html/PLAW-104publ191.htm

- Ng-Mak D, Halpern R, Rajagopalan K, et al. Hospitalization risk in bipolar disorder patients treated with lurasidone versus other atypical antipsychotics. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(2):211–219.

- Faries DE, Leon AC, Haro JM, et al. Chapter 9 analysis of longitudinal observational data using marginal structural models. In: Anal obs health care data using SAS®. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc.; 2010.

- Linden A, Adams JL. Evaluating health management programmes over time: application of propensity score-based weighting to longitudinal data. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16(1):180–185.

- Tunis SL, Ascher-Svanum H, Stensland M, et al. Assessing the value of antipsychotics for treating schizophrenia: the importance of evaluating and interpreting the clinical significance of individual service costs. Pharmacoeconomics. 2004;22(1):1–8.

- Hedman LC, Petrila J, Fisher WH, et al. State laws on emergency holds for mental health stabilization. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(5):529–535.

- Stensland M, Watson PR, Grazier KL. An examination of costs, charges, and payments for inpatient psychiatric treatment in community hospitals. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(7):666–671.

- Sanchez M, Lytle S, Neudecker M, et al. Medication adherence in pediatric patients with bipolar disorder: a systematic review. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2021;31(2):86–94.

- Feng JY, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Readmission after pediatric mental health admissions. Pediatrics. 2017;140(6):e20171571.

- Healy E, Fitzgerald M. A 16-year follow-up of a child inpatient population. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;9(1):46–53.

- Goldstein TR, Birmaher B, Axelson D, et al. History of suicide attempts in pediatric bipolar disorder: factors associated with increased risk. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7(6):525–535.

- Frías Á, Palma C, Farriols N. Comorbidity in pediatric bipolar disorder: prevalence, clinical impact, etiology and treatment. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:378–389.

- Fewell Z, Hernán MA, Wolfe F, et al. Controlling for time-dependent confounding using marginal structural models. The Stata Journal. 2004;4(4):402–420.