Abstract

Aims

The primary objective was to examine direct costs and health resource utilization (HRU) among commercially insured young adults with schizophrenia (SCZ) in Colorado.

Materials and methods

The Colorado All-Payer Claims Database, covering approximately 76% of the insured Colorado population was used. Members aged 18–34, with and without SCZ, having commercial insurance were included. All-cause, mental health (MH) related and non-MH related per patient per month (PPPM) costs and per hundred patients per month (PHPPM) HRU were compared between an SCZ cohort and a propensity score matched non-SCZ cohort before and after index date up to 48 months.

Results

Five hundred and one patients with SCZ and 2,510 matched individuals without SCZ were included. HRU and costs were higher for SCZ patients both pre- and post-index date. Pre-index, there were 32.3 (24.0 MH; 8.4 non-MH) PHPPM more office visits; 2.1 (2.7 MH) PHPPM more admissions; 104.8 (67.02 MH; 37.7 non-MH) PHPPM more prescriptions in the SCZ cohort (all p<.01). After index date, the SCZ cohort had 89.6 (81.3 MH; 9.2 non-MH) more PHPPM office visits, 7.2 (6.1 MH; 0.9 non-MH) PHPPM more admissions, and 181.6 (123.1 MH; 58.6 non-MH) PHPPM more prescriptions (all p<.001). All-cause costs in the pre-index period were $457 PPPM ($373 MH) higher for the SCZ cohort (p<.001). In the post-index period, all-cause costs for the SCZ cohort were $1,687 PPPM ($1,258 MH; $412 non-MH) higher (all p<.001). Approximately, 40% of patients with SCZ were on commercial insurance after four years compared with approximately 75% in the non-SCZ cohort.

Limitations

This study was based on data from a single state, thus may not be generalizable to other states.

Conclusions

Healthcare costs and HRU for young adults diagnosed with SCZ are significantly more burdensome to commercial payers than matched patients without SCZ, both before and after an official SCZ diagnosis.

Introduction

Schizophrenia (SCZ) is a chronic mental disorder characterized by deficiencies in thought processes, perceptions, emotional responsiveness, and social interactionsCitation1. Estimates for the prevalence of SCZ range from 0.25% to 1.1% of US adultsCitation1–3. Although it is possible for SCZ to occur at any age, the average age of onset is generally the late teens to the early 20s for men, and the late 20s to early 30s for womenCitation1,Citation4.

Due to the typical early onset and chronic nature of the condition, SCZ is one of the costliest illnesses worldwideCitation5, with financial costs disproportionately high relative to other chronic mental and physical health conditionsCitation6. Schizophrenia patients incur significant direct healthcare costs, including inpatient hospitalizations, prescription medications and hospital outpatient, emergency department (ED), physician office, and home healthcare visits. A recent claims-based analysis reported average overall annual costs for SCZ of $22,338 per patientCitation7. The overall economic burden of SCZ has been estimated to be over $155 billion, including direct healthcare ($37.7 billion), non-healthcare ($9.3 billion), and indirect costs ($117.3 billion)Citation8. These estimated costs convey the all-encompassing and pernicious nature of this disease including costs related to law enforcement, homelessness, unemployment, caregiving, and low productivity. Young adults aged 18–35 with SCZ have been shown to incur higher all-cause health resource utilization (HRU) and higher inpatient, outpatient, and ED costs compared to both non-schizophrenic controls and to older adults aged 36–64 years with SCZCitation7.

Medicaid plays a key role in covering and financing patients with mental illnessCitation9. Given the chronic nature of SCZ and considerable life challenges the disease imposes on these patients, they are likely to qualify for Medicaid coverage by having either a sufficiently low income or disabilityCitation9. As it is estimated that 87% of SCZ patients are covered by either Medicaid or MedicareCitation10, the smaller segment that is commercially insured may be overlooked. However, this disorder is often diagnosed in young adulthood, when patients may have commercial coverage through their parents. In fact, the prevalence of patients with SCZ in commercially insured populations has increasedCitation11 since the Affordable Care Act (ACA)Citation12 federally mandated the extension of commercial coverage to young adults up until age 26 years under their parents' health plans. Further, the share of commercial insurance paying for the care of young adults with psychoses has increased since the passage of the ACACitation13. Indeed, a study of Colorado residents found that 40% of young SCZ patients had commercial insurance 4 years after their initial diagnosisCitation14.

The primary objective of this study was to examine direct costs and healthcare resource utilization (HRU) among commercially insured young adults with SCZ in the state of Colorado, from one year prior to diagnosis to four years post-diagnosis. These data will inform payers, policy makers and population health decision makers around aspects of SCZ care and associated health resource burden during this critical period in the disease cycle.

Methods

Data source

Insurance claims between 1 January 2012 and 31 December 2019 from the Colorado All-Payer Claims Database (CO APCD) were used to conduct the study. The CO APCD captures health insurance claims data for the majority (76%) of insured beneficiaries living in the stateCitation15,Citation16. It contains anonymized claims from all insurers operating within the state (commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid). These data do not include claims from members who become incarcerated, or were covered by TRICARE, Veterans Administration, tribal health care, federal employee health benefits, self-insured payers that do not report their claims, or those that leave the stateCitation15,Citation17. The HIPAA and HITECH compliant de-identified data request was reviewed by the Data Release Review Committee and met all requirements for security and privacy.

Inclusion criteria

Schizophrenia cohort

Inclusion criteria for the SCZ cohort were: at least one inpatient or two outpatient (on separate days) claims for SCZ or schizoaffective disorder (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code: 295.xx; International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) code: F20.xx, F25.xx) (index date was defined as the date of the earliest SCZ or schizoaffective disorder diagnosis code), continuous medical insurance coverage of any type for at least 12 months prior to index date, aged 18–34 years on the index date, and commercial medical insurance coverage on the index date (Supplementary Figure 1). Commercial insurance coverage included any of the following: Commercial, Health Maintenance Organization (HMO), Indemnity Insurance, Point of Service (POS), Preferred Provider Organization (PPO), or Self-Funded. Members with overlapping commercial and public insurance coverage were considered commercially insured during the overlapping months as commercial insurance is typically the primary payer.

Non-schizophrenia cohort

For the non-schizophrenia (non-SCZ) cohort, a 25% random sample of all 18–34 year old residents without a diagnosis of SCZ or schizoaffective disorder at any point in their record was used. Additional inclusion criteria for the non-SCZ cohort were the same as the SCZ cohort. The index date was randomly assigned based on the distribution of index dates observed in the SCZ cohort.

Full inclusion criteria for both cohorts are described in Supplementary Figure 1.

Follow-up period

Members in both cohorts were followed for 48 months, until the individual had no more commercial enrollment records, or the end of the study period, whichever occurred first.

Propensity score matching

In order to minimize bias between the two cohorts, members were propensity score matched (PSM) on: age at index date, gender, year of index date, health statistics regionCitation18, number of insurance churn events (to account for insurance instability) in the year prior to diagnosis (baseline period), Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) scoreCitation19 in the baseline period, and the number of inpatient hospital admissions not related to mental health (MH) conditions in the baseline period (see Supplementary Table 5 for a list of codes defining related MH conditions). A "greedy" matching algorithm was used to match non-SCZ cohort members to SCZ cohort members at a 5:1 ratio using an established SASFootnote2 macroCitation20.

Endpoints assessed

The primary outcome measures of interest were HRU and healthcare costs. HRU per hundred patients per month (PHPPM) and allowed costs per patient per month (PPPM) were determined and compared for both the SCZ and non-SCZ cohorts as: all-cause (total); MH-related; and non-MH-related with further breakouts by inpatient visits, outpatient visits, ED visits, ancillary visits, and pharmacy-related. Ancillary visits were those with a place of service code that was not physician office-based care such as: skilled nursing facilities, rehabilitation facilities, assisted living facilities, homeless shelters, laboratories, pharmacies, etc. MH-related visits were those where the primary or admitting ICD diagnosis code was MH-related (Supplementary Table 6). Allowed costs consisted of the total payment (payer + patient) received by the provider for services rendered after adjudication. Patient out-of-pocket (OOP) costs were also assessed for differences between cohorts. In addition, the proportion of patients remaining on commercial insurance in each month from index date through 48 months was assessed.

Statistical analysis/definitions

Statistical differences between groups were determined by Chi-square test for categorical variables and the Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables. Longitudinal Poisson’s models (using generalized estimating equations (GEEs)) were constructed to estimate HRU and test for differences between the SCZ and non-SCZ cohorts in both the 12-month pre-index period and the 48-month post-index period. For health care costs, a gamma regression with a log link clustered at the patient level was used to estimate health care costs and test for differences between cohorts for both for the 12-month pre-index period and the 48-month post-index period. A gamma regression model with log link was also used to estimate costs and test for differences between cohorts in 6-month periods starting 12 months pre-index. Robust standard errors and 95% CIs were calculated.

Results

Cohort selection

Before PSM, there were 16,374 patients diagnosed with SCZ and 1,197,191 patients in the non-SCZ cohort aged 18–34 in the CO APCD. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, there were 516 and 133,164 individuals in the SCZ and non-SCZ cohorts; after PSM, there were 501 patients in the SCZ cohort and 2,510 patients in the non-SCZ cohort (Supplementary Figure 1).

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics (pre- and post-PSM) are summarized in . Before PSM, 67% and 48% (p<.001) of individuals were male in the SCZ cohort and non-SCZ cohorts, respectively, with a median age of 23 and 27 years (p<.001). In the SCZ cohort, 68% of patients were aged 18–25, while in the non-SCZ cohort, the proportion in that age group was 43% (p<.001). Within the SCZ cohort, 53% had insurance through their employer (vs. 59% non-SCZ), 40% were the child of an employed/covered parent (vs. 27% non-SCZ), 7.6% were dependents/spouses/unknown (vs. 13.7%), (all p<.001). Patients in the SCZ cohort were more likely to have been covered by Medicaid at some point prior to the index date (30% vs. 8.5%; p<.001). Patients with SCZ had a higher number of prior non-MH inpatient admissions (20.3% with at least one visit vs. 8.3%; p<.001) and higher CCI scores than members of the non-SCZ cohort (11.0% of scores greater than 0 vs. 5.1%; p<.001). 29.9% of patients with SCZ had at least one insurance churn event during the baseline period compared to 18.3% of the non-SCZ cohort (p<.001) (). Following PSM, the cohorts were well matched on all variables with the exception of type of commercial insurance ().

Table 1. Baseline cohort characteristics.a

Prior MH conditions were seen in both groups but were much more common in the SCZ cohort (75% and 26%) (Supplementary Figure 2a). The most frequently reported diagnosis in the SCZ cohort was “other psychotic disorders” (44%). Bipolar and related disorders were reported in 26% of patients; trauma and stressor-related disorders in 20% of patients. In addition, depressive disorders (39%), anxiety disorders (37%), substance-related and addictive disorders (32%) were common. In the non-SCZ cohort, all categories were significantly below the SCZ cohort, with the most common being anxiety disorders (11%), depressive disorders (9%), and substance-related and addictive disorders (7%) (all p<.001). Prior non-MH conditions were uncommon in both the SCZ and non-SCZ cohorts, with the most common being chronic pulmonary disease 8% and 7% (p=.452) as defined by the Elixhauser Comorbidities ScaleCitation19, and other neurological disorders (7% and 2%, p<.01) (Supplementary Figure 2b).

Continuity of commercial coverage

Both cohorts saw a decline in individuals with commercial insurance from index date to 48 months after index date (Supplementary Figure 3). The decline was greatest in the first 8–10 months, after which point the decline slowed and was relatively constant. The decline in continuity of commercial coverage was greater in the SCZ cohort: at 12 months post-index date, the proportion of patients in the SCZ cohort with commercial insurance dropped to 69% vs. 86% in the non-SCZ cohort; at 48 months, only 38% of the SCZ cohort remained commercially insured vs. 74% of the non-SCZ cohort, respectively.

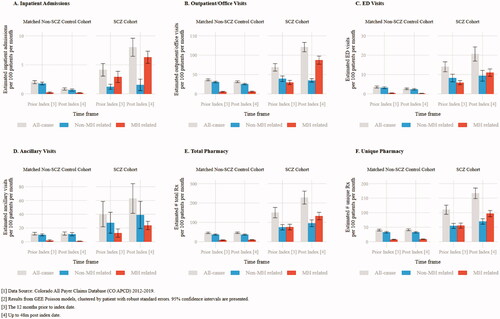

Pre-index health resource utilization

Health care utilization was reported in counts PHPPM. In the 12 months prior to the index date, all-cause utilization was higher in the SCZ cohort compared to the non-SCZ cohort for average inpatient admissions (4.14 PHPPM vs. 2.02; p<.001), average outpatient/office visits (68.61 vs. 36.29; p<.001), average ED visits (14.02 vs. 3.56; p<.001), ancillary services (40.15 vs. 11.71; p=.003), and average number of prescriptions (150.45 vs. 45.69; p<.001) (; Supplementary Table 1). Inpatient admissions, outpatient/office visits, and prescription medications; the increase in utilization was driven primarily by MH related utilization (; Supplementary Table 1). For example, the SCZ cohort had 23.98 PHPPM (p<.001) more MH related and 8.37 PHPPM (p=.028) more non-MH related outpatient/office visits in the one year prior to index date (; Supplementary Table 1b). In addition, the SCZ cohort averaged 2.69 PHPPM (p<.001) more MH related inpatient admits (; Supplementary Table 1a), 67.02 PHPPM (p<.001) more MH related prescriptions and 21.84 PHPPM (p<.001) more non-MH related prescriptions over the year prior to index date (; Supplementary Table 1e). The SCZ cohort also had 5.41 PHPPM more MH related (p<.001) and 5.03 PHPPM more non-MH related (p<.001) ED visits in the pre-index period (; Supplementary Table 1c).

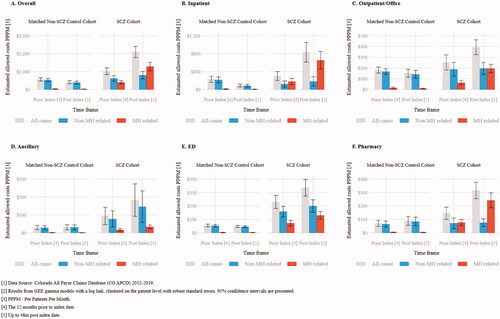

Pre-index costs

In the one year prior to index date, the all-cause PPPM allowed costs were higher in the SCZ cohort compared to the non-SCZ cohort ($1,021 PPPM vs. $564 PPPM; p<.001) (; Supplementary Table 2a). Pre-index costs were primary driven by MH related costs with patients in the SCZ cohort averaging $373 PPPM higher MH related costs (p<.001) in the pre-index period (; Supplementary Table 2a). The ED setting had the largest component of pre-index costs for the all-cause, MH, and non-MH related components. The SCZ cohort had $174 PPPM greater all-cause ED costs (p<.001), $69 PPPM greater MH related (p<.001) ED costs, and $105 PPPM greater (p<.001) non-MH related ED costs (; Supplementary Table 2e).

Post-index HRU

In the 48 months post-index, the SCZ cohort incurred higher HRU across all categories of service compared to the non-SCZ cohort (p<.001 in all categories): inpatient admits (8.03 PHPPM vs. 0.84 PHPPM), outpatient/office visits (120.95 PHPPM vs. 31.35 PHPPM), ED visits (20.60 PHPPM vs. 2.61 PHPPM), ancillary visits (62.88 PHPPM vs. 11.79 PHPPM), and prescriptions (228.07 PHPPM vs. 46.50 PHPPM total prescriptions and 166.87 PHPPM vs. 41.26 PHPPM unique prescriptions) (, Supplemental Table 1a–f). Across all categories, peak utilization was seen for the SCZ cohort in the index month, reflecting the resource use associated with the index diagnosis (Supplementary Figure 4a–e). While utilization in the months after index leveled off relative to peak utilization for the different resource categories, the SCZ cohort had consistently greater utilization every month (Supplementary Figure 4a–e). Mental health related utilization was significantly higher among patients in the SCZ cohort across all utilization settings (inpatient admits: 6.14 PHPPM greater, p<.001; outpatient/office visits: 81.26 PHPPM greater, p<.001; ED visits 10.75 PHPPM greater, p<.001; ancillary visits 22.86 PHPPM greater; total prescription medications: 123.10 PHPPM greater, p<.001; and unique prescription medications 88.33 PHPPM, p<.001) (), Supplemental Table 1a–f). While MH related utilization accounted for much of the overall utilization, in many service categories, non-MH utilization contributed as well. In the post-index period, the SCZ cohort had higher non-MH related outpatient/office visits (9.21 PHPPM greater, p<.001), ED visits (6.97 PHPPM greater, p<.001), ancillary visits (27.96 PHPPM greater, p=.024), total and unique prescription medications (58.60 PHPPM greater and 37.30 PHPPM greater, respectively; p<.001) (, Supplemental Table 1a–f).

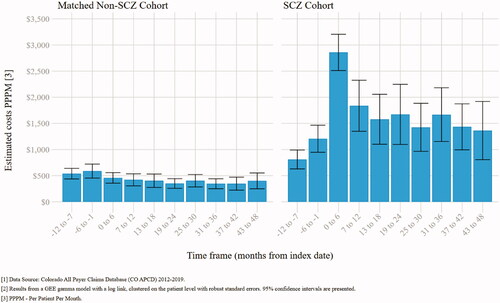

Post-index costs

In the 48 months after index-date, allowed costs were consistently higher in the SCZ cohort compared to the non-SCZ cohort in each 6-month interval (p<.001) (; Supplementary Table 3). The peak difference was in the 0–6 months period from index date ($2,858 PPPM vs. $457; p<.001), while the smallest difference was in the 43–48 months period ($1,362 PPPM vs. $400; p<.001). Across all 48 months of follow-up, SCZ patients incurred $1,687 PPPM (95% CI: $1,365–$2,008) more costs than non-SCZ patients (, Supplemental Table 2a).

Figure 3. Average PPPM commercial allowed costs in 6-month intervals (n = 3,011)Citation1,Citation2.

Higher overall costs were driven by both non-MH and MH related components with the SCZ cohort having $412 PPPM greater non-MH (p<.001) and $1,258 (p<.001) greater MH allowed costs over the 48 months following index date. Mental health related costs in the SCZ cohort over the 48 months post-index were greater than the non-SCZ cohort across all settings including: inpatient admits ($1,258 PPPM greater, p<.001), outpatient/office visits ($186 PPPM greater, p<.001), ancillary visits ($33 PPPM greater, p<.001), ED visits ($127 PPPM greater, p<.001), and prescription medications ($238 PPPM greater, p<.001). Patients in the SCZ cohort had higher non-MH related costs for ancillary visits ($115 PPPM greater, p=.11) and ED visits ($154 PPPM greater, p<.001) compared to the non-SCZ cohort (, Supplementary Table 2d–e).

Across all service categories, neither MH nor non-mental related costs increased for the non-SCZ cohort (; Supplementary Table 2b–f) over this period.

Out-of-pocket costs

In the pre-index period, overall, OOP costs were higher for patients with SCZ than without ($117 PPPM vs. $69 PPPM; p<.001). Forty-four percent of those OOP costs were due to MH related services in the SCZ cohort compared to 8% in the non-SCZ cohort. The largest portion of pre-index OOP costs in the SCZ cohort was due to ED visits ($25 PPPM vs. $9 PPPM; p<.001). In the post-index period, OOP costs in the SCZ cohort rose to $206 PPPM. This was $153 PPPM (p<.001) higher than the non-SCZ cohort. Mental health related OOP costs were unchanged in the non-SCZ cohort over the 48-month evaluation period. However, in the SCZ cohort, MH related OOP costs rose to $131 PPPM ($126 PPPM higher than the non-SCZ cohort; p<.001). Non MH related OOP costs also increased in the SCZ cohort. In the post-index period, the SCZ cohort averaged $26 PPPM greater OOP costs than the non-SCZ cohort (p<.001) (Supplemental Table 4a–f).

Discussion

This study found that commercially insured, young adults with SCZ residing in Colorado used more healthcare resources and incurred higher costs, both before and after their SCZ diagnosis, compared to a matched cohort of young adults without SCZ. These differences are due to increased utilization and costs from both MH related and non-MH related services.

Schizophrenia is a diagnosis of exclusion that also requires symptoms to persist for at least six monthsCitation21, thus lending itself to not being formally diagnosed until well after symptoms begin to appearCitation22. In a recent US study examining the time period 1–5 years prior to a diagnosis of SCZ, patients exhibited all-cause costs 1.7–3.1 times that of matched non-SCZ patientsCitation23. A further study of the same data showed higher HRU for SCZ patients during the same pre-diagnosis time periodCitation24. The current study observed all-cause costs of $1,021 PPPM for the SCZ cohort, which is 1.8 times that of patients without SCZ in the 1 year prior to diagnosis with the increased cost seen in each specific health care setting including non-MH related services. Not surprisingly, there was a corresponding greater utilization of healthcare resources across settings for SCZ patients before their official diagnosis, including outpatient/office visits, ED visits, ancillary visits, and prescription medications. Notably, a significant portion of this pre-index utilization was due to non-MH related services as well as MH related. This finding supports the aforementioned studies and indicates that these patients carry a high payer burden in the time period prior to a formal diagnosis and ensuing treatment for SCZ and that the burden is not only due to MH related care.

Once diagnosed, there were increases in costs and HRU in the SCZ cohort compared to the pre-index period. The largest increases in costs and HRU was seen in the first six months after diagnosis, driven by hospitalizations associated with an acute health service event (e.g. a psychotic episode) leading to the initial SCZ diagnosis. Of note, over the 48-month follow-up period, overall costs do not return to pre-index levels after the initial increase. Mental health-related inpatient, outpatient, and ED costs; and outpatient, ancillary, and prescription HRU all increased and remained elevated after the initial six-month peak. At the same time, in the post index period, costs related to non-MH services also increased almost 30% from the pre-index level. As these patients are receiving increased care, other health conditions may also be discovered and treated, leading to higher non-MH costs. This highlights the complex chronic nature of SCZ and persistent payer burden of the disease.

When compared to the matched non-SCZ cohort, the SCZ cohort exhibited five times higher overall PPPM costs ($2,097 vs. $411 for the SCZ and non-SCZ cohorts respectively). For HRU, the increase depended on the health care setting, with between 6 and 81 more visits PHPPM and 123 more prescriptions PHPPM. This corresponds with other studies conducted among commercially insured SCZ patientsCitation8,Citation11. Evidence for the significant burden to commercial payers is strengthened by our study with its added focus on the younger SCZ population.

Our study also showed demographic and clinical differences between those with and without SCZ. Before propensity score matching, the population of patients with SCZ had a higher proportion of males, a lower median age, and more often had a dependent relationship with the health insurance subscriber at index date than those without SCZ. Clinically, the SCZ cohort had higher CCI scores, indicating worse overall health even prior to their SCZ diagnosis. The increase in non-MH related utilization and costs was observed both prior to and following index reflects this.

The SCZ cohort had significantly more MH comorbidities than matched patients without SCZ in the pre-index period, which is consistent with other studiesCitation25–27. In addition, SCZ is not a sudden-onset condition with cognitive impairment and unusual behaviors sometimes appearing as early as childhoodCitation1,Citation4. As this is a young adult population, the high proportion of SCZ patients exhibiting MH comorbidities prior to diagnosis (i.e. depression, anxiety) may be due to misdiagnosis in adolescence or a prodromal symptom of SCZCitation28. Available data from heterogeneous studies also suggest a 25% prevalence of panic attacks and a 15% prevalence of panic disorder in patients with SCZCitation29. The higher disease burden for these patients leading up to diagnosis helps explain the higher costs and HRU in the pre-index period found in this study.

Remission is the ideal outcome for SCZ treatment and is associated with subjective well-being and better functional outcomes and is achieved in 20–60% of patientsCitation30. However, relapse, which itself incurs cost and HRU, is common in patients with SCZ. While relapse is mainly associated with stopping or reducing treatmentCitation31, patients with chronic illness who adhere to long-term treatment have an increased risk of relapse, suggesting that early intervention to prevent relapse may benefit patients and be cost effectiveCitation32. The use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) for treating first‐episode SCZ, shows promise as a way to control the disease and prevent relapseCitation33,Citation34. Life-long treatment is needed for SCZ, including both pharmacological and psychological treatmentCitation11. While this represents a significant financial and resource burden to commercial insurers, it also represents an opportunity to prevent further costs and improve patient outcomes with early and consistent treatment.

Finally, we also observed that patients with SCZ moved from commercial to public insurance both more quickly and more often than those without SCZ, with less than 40% of patients with SCZ remaining on commercial insurance by year 4, compared with approximately 75% of those without SCZ. A prior study of these data showed that 52.4% of patients with SCZ switched to public insurance within 48 months of being diagnosed compared to 10.7% without SCZCitation14. This is likely due to aging out of their parent’s commercial coverage after age 26, or not being able to sustain employment with commercial insurance coverage. Even with this reduction of commercially insured patients, more than one third of patients remain on commercial insurance 4 years after diagnosis, showing that this is a large and costly population for commercial insurance companies to cover. The complex nature of diagnosis and treatment of this population means that it could take a considerable amount of time for their psychoses to be properly managed and controlled. Commercial payers can create policies to better treat these patients while under their care as opposed to relying on public payers to manage them. One such solution would be the removal of prior authorization or step-therapy policies for the use of LAIs. There is a growing body of evidence that LAIs are more effective at controlling symptoms, preventing relapse, hospitalization, and reducing costs compared to oral antipsychoticsCitation33,Citation35–38. A recent meta-analysis comparing the use of LAIs vs. oral antipsychotics found that LAIs were superior to oral antipsychotics for hospitalization and relapse riskCitation35. A review of LAI use in early onset SCZ showed their use had better adherence, lower relapse rates, increased remission rates, reduced symptomatology, and the potential to be neuroprotectiveCitation33. This review also noted that LAIs use as a fist line therapy is cost effective and that the better adherence rates lead to lower SCZ related costs. Another meta-analysis comparing LAIs to oral antipsychotics found reduced hospital and emergency room admissions as well as increased adherence. In their analysis, there was no difference in all-cause health care costCitation36.

Our study has several limitations. Caution is required when generalizing these findings since the dataset only comprises patients living and insured in the state of Colorado. We did not investigate for differences between patients who were the primary beneficiary verses the dependent, which may mask differences between SCZ patients that can and cannot maintain employment. Since our sample included patients that could remain on their parents’ commercial coverage until age 26, it is possible that the commercial attrition observed is influenced by these patients aging out of their parents’ coverage and being forced to find their own or forego insurance coverage. The extent of this influence may be mitigated however as 51.9% of the SCZ cohort were listed as having their own insurance through an employer as opposed to 40.3% listed as a child. Claims data used for this analysis are generated for reimbursement, not research, and coding errors, misclassification, diagnostic uncertainty, and/or omissions could affect the reliability of the findings. Specifically, we could not clinically validate any diagnoses in this study because of privacy regulations and because the data were de-identified. In addition, in this study, we used SCZ diagnosis as the index date when analyzing costs and HRU; this marker may not capture the fluidity of identifying this disease, especially at onset. Nevertheless, health insurance claims data remain a valuable source of information because they contain a large and valid sample of patient characteristics in a real-world setting.

Conclusions

A substantial proportion of young adults diagnosed with SCZ while commercially insured remain on commercial insurance for up to four years. These patients' costs and HRU are significantly more burdensome to commercial payers than matched patients without SCZ, both before and after an official SCZ diagnosis. This finding highlights the need for intervention with evidence-based care for this vulnerable, challenging, and costly patient population.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This research was sponsored by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

JP, CP, and CB are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, and are stockholders of Johnson & Johnson. DR, EP, and RP are affiliated with SmartAnalyst Inc., New York, NY, USA, and their work on this study was funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

JP, CP, DR, EP, RP, and CB contributed to the conception and design of the study. JP, RP, and EP acquired the data. Data analysis was conducted by DR, EP, and RP. All authors contributed to data interpretation and drafting of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the article for important intellectual content and approved the final draft for submission.

Previous presentations

Data in this manuscript have been presented at the Psych Congress 2020 Virtual Experience; September 10–13, 2020.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (5.7 MB)Acknowledgements

This study used the CO APCD database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Medical writing support for the development of this manuscript was provided by Chris Whittaker, PhD of Ashfield MedComms Macclesfield, United Kingdom, an Ashfield Health company, and was funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Data availability statement

The data sets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the proprietary nature of the database from which they were derived and used under license for the current study. For questions regarding data sharing, please contact Jacqueline Pesa at [email protected].

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2021.2012983)

Notes

1 These 21 regions within Colorado were developed by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. They were determined by county population size, demographic factors, and the number of communities served by each county health department.

2 SAS Inc. (Cary, NC).

References

- What is schizophrenia? | NAMI: National Alliance on Mental Illness [Internet]; [cited 2021 Jun 1]. Available from: https://www.nami.org/About-Mental-Illness/Mental-Health-Conditions/Schizophrenia/Overview

- McGrath J, Saha S, Chant D, et al. Schizophrenia: a concise overview of incidence, prevalence, and mortality. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30(1):67–76.

- Hollis C, Rapoport J. Child and adolescent schizophrenia. In: Weinberger D, Harrison P, editors. Schizophrenia. 3rd ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. p. 24–46. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444327298.ch3

- NIMH. Schizophrenia [Internet]; [cited 2021 Jun 1]. Available from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/schizophrenia

- Rössler W, Joachim Salize H, Van Os J, et al. Size of burden of schizophrenia and psychotic disorders. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;15(4):399–409.

- Desai PR, Lawson KA, Barner JC, et al. Estimating the direct and indirect costs for community-dwelling patients with schizophrenia. J Pharm Heal Serv Res. 2013;4(4):187–194.

- Huang A, Amos TB, Joshi K, et al. Understanding healthcare burden and treatment patterns among young adults with schizophrenia. J Med Econ. 2018;21(10):1026–1035.

- Cloutier M, Aigbogun MS, Guerin A, et al. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2013. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(6):764–771.

- Zur J, Musumeci M, Garfield R. Medicaid’s role in financing behavioral health services for low-income individuals; [Internet]; [cited 2021 Jun 1]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaids-role-in-financing-behavioral-health-services-for-low-income-individuals/

- Khaykin E, Eaton WW, Ford DE, et al. Health insurance coverage among persons with schizophrenia in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(8):830–834.

- Fitch K, Iwasaki K, Villa KF. Resource utilization and cost in a commercially insured population with schizophrenia. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2014;7:18–26.

- Health insurance coverage for children and young adults under 26 | HealthCare.gov [Internet]; 2021 [cited 2021 Jun 1]. Available from: https://www.healthcare.gov/young-adults/children-under-26/

- Busch SH, Golberstein E, Goldman HH, et al. Effects of ACA expansion of dependent coverage on hospital-based care of young adults with early psychosis. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(11):1027–1033.

- Pesa J, Rotter D, Papademetriou E, et al. Real world analysis of insurance churn among young adult patients with schizophrenia using the Colorado All Payer Claims Database (CO-APCD) | Psychiatry & Behavioral Health Learning Network. Psych Congr [Internet]. Virtual; 2020; [cited 2021 Jun 1]. Available from: https://www.psychcongress.com/posters/real-world-analysis-insurance-churn-among-young-adult-patients-schizophrenia-using-colorado

- What’s in the CO APCD? CIVHC.org [Internet]; 2021 [cited 2021 Jun 1]. Available from: https://www.civhc.org/get-data/whats-in-the-co-apcd/

- CO APCD Info – CIVHC.org [Internet]; 2021 [cited 2021 Jun 1]. Available from: https://www.civhc.org/get-data/co-apcd-info/

- Capabilities of the Colorado All Payer Claims Database Type of Information What You Can’t Do With Claims Alone What You Can’t Do With the CO APCD Currently* What You CAN Do With the CO APCD Right Now Claim Type and Specifics [Internet]. Cent. Improv. Value Heal. Care. Capab. Color. All Payer Claims Database; 2017 [cited 2021 Jun 1]. Available from: http://www.civhc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/CO-APCD-Capabilities_Oct-2017_Final.pdf

- Colorado Health Institute. Colorado health access survey methodology report [Internet]; 2015 [cited 2021 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.shadac.org/sites/default/files/CO_2015_HH_Methodology.pdf

- Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–1139.

- Parsons LS. Performing a 1: N Case-Control Match on Propensity Score. SAS Conf Proc SAS Users Gr Int 29; [Internet]; 2004; Montreal: Paper 165-29. Available from: https://support.sas.com/resources/pap; https://support.sas.com/resources/papers/proceedings/proceedings/sugi29/165-29.pdf

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders [Internet]. American Psychiatric Association; 2013 [cited 2021 Jun 1]. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Hensel JM, Chartier MJ, Ekuma O, et al. Risk and associated factors for a future schizophrenia diagnosis after an index diagnosis of unspecified psychotic disorder: a population-based study. J Psychiatr Res. 2019;114:105–112.

- Wallace A, Barron J, York W, et al. Health care resource utilization and cost before initial schizophrenia diagnosis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;1–10.

- Wallace A, Isenberg K, York W, et al. Detecting schizophrenia early: prediagnosis healthcare utilization characteristics of patients with schizophrenia may aid early detection. Schizophr Res. 2020;215:392–398.

- Rosen JL, Miller TJ, D'Andrea JT, et al. Comorbid diagnoses in patients meeting criteria for the schizophrenia prodrome. Schizophr Res. 2006;85(1–3):124–131.

- Öngür D, Lin L, Cohen BM. Clinical characteristics influencing age at onset in psychotic disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50(1):13–19.

- Chuma J, Mahadun P. Predicting the development of schizophrenia in high-risk populations: systematic review of the predictive validity of prodromal criteria. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(5):361–366.

- White T, Anjum A, Schulz SC. The schizophrenia prodrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):376–380.

- Buckley PF, Miller BJ, Lehrer DS, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities and schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(2):383–402.

- Yeomans D, Taylor M, Currie A, et al. Resolution and remission in schizophrenia: getting well and staying well [Internet]. Advances in psychiatric treatment. Cambridge University Press; 2010 [cited 2021 Jun 1]. p. 86–95. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/advances-in-psychiatric-treatment/article/resolution-and-remission-in-schizophrenia-getting-well-and-staying-well/767E7B84B3EA3BDD8D81521EB80882E8

- Emsley R, Chiliza B, Asmal L, et al. The nature of relapse in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:50.

- Alphs L, Nasrallah HA, Bossie CA, et al. Factors associated with relapse in schizophrenia despite adherence to long-acting injectable antipsychotic therapy. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;31(4):202–209.

- Stevens GL, Dawson G, Zummo J. Clinical benefits and impact of early use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics for schizophrenia. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2016;10(5):365–377.

- Brissos S, Veguilla MR, Taylor D, et al. The role of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a critical appraisal. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(5):198–219.

- Kishimoto T, Hagi K, Kurokawa S, et al. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics for the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and comparative meta-analysis of randomised, cohort, and pre–post studies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(5):387–404.

- Lin D, Thompson-Leduc P, Ghelerter I, et al. Real-world evidence of the clinical and economic impact of long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics among patients with schizophrenia in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CNS Drugs. 2021;35:469–481.

- De Berardis D, Marini S, Carano A, et al. Efficacy and safety of long acting injectable atypical antipsychotics: a review. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2013;8(3):256–264.

- De Berardis D, Vellante F, Olivieri L, et al. The effect of paliperidone palmitate long-acting injectable (PP-LAI) on “non-core” symptoms of schizophrenia: a retrospective, collaborative, multicenter study in the “real world” everyday clinical practice. Riv Psichiatr. 2021;56(3):143–148.