Abstract

Aim

To estimate the incremental phase-specific and lifetime economic burden among newly diagnosed cervical and endometrial cancer patients vs. non-cancer controls.

Methods

Cervical and endometrial cancer patients newly diagnosed between January 2015 and June 2018 were identified in the Optum Clinformatics DataMart database. The index date was the date of the first diagnosis for cancer cases and the first claim date after 12 months of continuous enrollment for non-cancer controls. Patients were followed until death/loss of enrollment/end of data availability. Per patient per month (PPPM) costs attributable to cancer were calculated for four phases: pre-diagnosis (3 months before diagnosis), initial (6 months post-diagnosis), terminal (6 months pre-death), and continuation (remaining time between initial and terminal phases). Survival data were obtained to determine the monthly proportion of patients in each phase. Total survival adjusted monthly costs were obtained by multiplying the proportion of patients in each phase by the total cost incurred during that month. Phase-specific and lifetime incremental costs of cervical and endometrial cancer were obtained using generalized linear models.

Results

The analytic cohort included 1,002 cervical cancer patients and 4,005 matched non-cancer controls and 5,003 endometrial cancer patients matched with 19,999 non-cancer controls. Mean adjusted incremental PPPM lifetime costs (95% CI) for cervical cancer and endometrial cancer cases were $5,910 ($5,373–$6,446) and $3,475 ($3,259–$3,691), respectively. Incremental total PPPM phase-specific costs attributable to cervical and endometrial cancer were pre-diagnosis (cervical: $1,057; endometrial: $3,315), initial ($12,084; $8,618), continuation ($2,732; $1,147), and terminal ($2,702; $5,442). Incremental costs were significantly higher for cancer patients vs. non-cancer controls across patient lifetime and all phases of care (except terminal phase costs for cervical cancer). Outpatient costs were the major driver of costs across all post-diagnosis phases.

Conclusion

This study highlights the cost burden associated with cervical/endometrial cancer and cost variation by phases of care.

Introduction

Cancers of the cervix and the uterine corpus are two of the most common malignancies of the female reproductive system in the United States (US). In 2019, cervical and uterine cancers accounted for an estimated 12% and 57%, respectively, of newly diagnosed gynecological cancers in the USCitation1. While the widespread adoption of screening has contributed to a significant decline in the incidence of cervical cancer, the number of patients diagnosed with advanced disease has continued to riseCitation2. A large proportion of cervical cancer patients (52%) present with regional or distant disease at diagnosisCitation3. This in turn has contributed to an estimated 5-year survival rate of 66.1% among cervical cancer patientsCitation3. Adenocarcinomas of the endometrium are the most common gynecological cancers, accounting for over 90% of uterine cancer casesCitation1. Unlike patients diagnosed with other gynecological cancers, a majority of endometrial cancer patients (67%) are diagnosed at an early stage, resulting in an 81.2% 5-year survival rateCitation4. Treatment of cervical and endometrial cancer requires consideration of the type and stage of cancer and the desire to maintain fertility. These treatment considerations coupled with the higher overall survival in this patient population in turn affect the accumulation of health care costs over the patient’s lifetime.

The phase-of-care approach is one method that can be used to estimate the long-term costs of cancer care; it divides patients’ follow-up period into clinically meaningful time periodsCitation5–7. Previous studies have reported the health care costs accrued by cancer patients in multiple phases of care. These studies’ findings indicate that health care costs in cancer patients follow a U-shaped curve across the care continuum. Specifically, costs are expected to rise in the time after diagnosis and again toward the end of lifeCitation8,Citation9. A study conducted by Yabroff et al. summarized the net costs of care for elderly cancer patients using data obtained from the 1999 to 2003 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)–Medicare files. These authors reported that women diagnosed with cancers of the cervix and the corpus uteri had the highest total incremental costs during the last year of life, followed by the initial 12 months after cancer diagnosisCitation5. It is important to note that the treatment landscape for gynecological cancers has changed since the study conducted by Yabroff et al. Therefore, there is a need for a more contemporary analysis of the phase-specific costs associated with cervical and endometrial cancer.

Studies to date, however, have not estimated the longitudinal accumulation of direct medical costs from diagnosis to death among newly diagnosed cervical and endometrial cancer patients in a commercially insured US population. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to describe the lifetime economic burden of treating cervical and endometrial cancer stratified by phase of care and to determine the drivers of costs associated with cervical and endometrial cancer in each phase in a commercially insured US population.

Methods

Data source

This study is a retrospective database analysis using data obtained from the 2014–2019 Optum Clinformatics DataMart, a nationally representative US claims database containing aggregated medical, laboratory, and prescription claims. The database includes information on 45 million individuals and up to 500,000 Medicare beneficiaries. Mortality data for the study cohort were obtained from the Death Master File (DMF) provided by the Social Security Administration (SSA). The DMF provides the name, birth date, and date of death of each deceased person reported to the SSA and can be linked to the claims dataset using a unique encrypted patient ID variable.

Study population

The study population included incident cervical and endometrial cancer patients diagnosed between January 2015 and June 2018 matched to non-cancer controls. Eligible cancer patients and non-cancer controls were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revisions, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM) diagnosis codes. Cervical cancer patients were identified using the ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes of 180.x and ICD-10-CM codes of C53.x. Endometrial cancer patients were identified using ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes of 182.0–182.8 and ICD-10-CM codes of C54.0–C54.9 and C55.9.

Adult (≥18 years of age) cancer patients were included if they met the following criteria: (1) two or more diagnosis codes for cervical or endometrial cancer within a 2-month period, (2) continuous enrollment for ≥12 months before and ≥6 months after the first cervical or endometrial cancer diagnosis.

Cancer patients were excluded if they had: (1) a diagnosis of other cancers in the ≤12 months before the first diagnosis of cervical or endometrial cancer, (2) diagnosis or procedure codes for metastasis, systemic therapy, RT, or gynecological cancer–related surgeries (hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, conization, trachelectomy, or lymphadenectomy) in the ≤12 months before the first diagnosis date of cervical or endometrial cancer. The index date for cancer cases was the date of the first cervical or endometrial cancer diagnosis.

Non-cancer controls included patients without cancer-related ICD-9-CM (140.x–239.x) or ICD-10-CM (C000-D3A8) diagnosis codes, and with at least 12 months of continuous enrollment in the Optum Clinformatics DataMart database. Non-cancer controls were assigned a pseudo-index date that was defined as the first claim date after a 12-month period of continuous enrollment. A pseudo-index date was assigned because there were no specific diagnoses or treatments of interest for non-cancer controls. Cancer cases and non-cancer controls were followed from the index date until death, loss of enrollment, or the end of the study period, whichever occurred first.

Baseline covariates

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics were assessed for cancer cases and non-cancer controls in the 12 months before the index date. Key demographic variables extracted were age at index date, geographic region, health insurance type, and index year. Comorbidities during the baseline period were summarized using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)Citation10. The covariates used to describe cancer cases and non-cancer controls were selected based on their clinical relevance and their availability in the administrative claims database.

Health care costs

The primary outcomes of interest were the lifetime and phase-specific costs associated with cervical and endometrial cancer from a health care payer perspective. Direct medical costs (the allowed charges) accrued by cases and non-cancer controls were aggregated for each month of follow-up and were categorized as inpatient, emergency department (ED), outpatient, or prescription costs. Direct medical costs for cancer patients and non-cancer controls used in this study correspond to the standardized costs reported by Optum. Standardized costs are calculated by Optum researchers using algorithms that account for variations in allowed charges across health plans and provider contractsCitation11,Citation12. Direct non-medical costs, such as lost time due to travel to a health care facility, and indirect costs associated with lost work productivity and absenteeism were not considered since they are not captured in the database. Total direct medical costs (the allowed charges) for each month were obtained by summing the individual component costs for a specific month. All costs were standardized to 2018 US dollars using the Consumer Price Index for medical care from the US Bureau of Labor StatisticsCitation13.

Newly diagnosed cervical and endometrial cancer patients were then matched with up to 4 non-cancer controls on the propensity score, index year, and year of the last follow-up using a greedy matching algorithm without replacementCitation14. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to estimate the propensity of receiving a cervical or endometrial cancer diagnosis conditional on baseline covariates (age at index date, geographic region, health insurance type, and CCI score).

Definition of phases of care

The total follow-up period for each case-control pair before and after the index date was divided into four phases of care (). The phases of care included pre-diagnosis (3 months before diagnosis), initial (6 months post-diagnosis), terminal (6 months before death or end of follow-up), and continuation (any remaining time between the initial and terminal phases). A 3-month pre-diagnosis phase was included to account for the costs associated with cancer-related symptoms and the testing required to establish a cancer diagnosis. Previous real-world studies have shown that rates of inpatient hospitalizations, ED visits, and outpatient visits substantially increase in the 3 months leading up to a cancer diagnosisCitation15,Citation16. A 6-month initial phase of care was included to reflect the primary course of treatment recommended for newly diagnosed cancer patients and any subsequent adjuvant therapyCitation7,Citation17. A 6-month terminal phase was chosen to reflect the resource- and cost-intensive period observed before deathCitation18,Citation19. The length of the continuation phase of care, which corresponds to long-term maintenance therapy and the treatments given as patients progress, was not pre-defined since the time between the primary course of treatment and death can vary substantially among newly diagnosed cancer patientsCitation17,Citation20. In summary, the lengths of the phases of care were chosen based on clinical knowledge, prior studies that have used phase-specific approaches to estimate health care costs of cancer patients across several indications, and the inflection points in cumulative costs observed in our analysis. Previous studies have used similar data-driven approaches, such as joinpoint regression analyses, to determine the duration of the phases of care based on inflection points in monthly cost trendsCitation21.

Patients who died within 6 months of follow-up (all-cause mortality) had all costs attributed to the terminal phase, while patients who died after at least 6 months of follow-up had their post-index costs first assigned to the terminal phase, with any remaining time assigned to the initial phase followed by the continuation phase. Patients who did not die during follow-up had their post-index costs attributed to the initial and continuation phases (up to 6 months before the end of follow-up). Therefore, cases and controls without a death date contributed data only to the continuation phase and not to the terminal phase, ensuring that there was no biased estimation of costs in the terminal phase of care.

Statistical analysis

The probability of survival at each month was calculated for the first 24 months of observation after the index date (initial and continuation phases) and for all months of the terminal phase (months 1–6). A preliminary check of mortality data for cases and controls showed only 5% of the patients in this study reached the terminal phase of care. Therefore, survival probabilities for cervical cancer patients were obtained from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)*Explorer website, which provides mortality data by cancer siteCitation22. SEER is a valuable resource for mortality data, given that it collects and publishes data on cancer incidence and survival from various cancer registries that are representative of the US cancer population. The 2017 US life tables from the National Center for Health Statistics provided survival probabilities for non-cancer controlsCitation23. The total survival adjusted monthly health care costs were obtained by multiplying the proportion of patients in each phase by the total cost incurred during that month.

The average monthly cost of patients in the pre-diagnosis phase was not adjusted for censoring, as all patients had 3 months of data in the pre-diagnosis phase. The monthly adjusted costs for the first 24 months after the index date (initial and continuation phases) were calculated by weighting the cost attributable to each month by the probability of survival in that month. The monthly costs for subsequent months of follow-up (on or after 25 months of follow-up) were assumed to remain constant in the non-terminal phase. The monthly cost of the terminal phase was obtained by multiplying the average cost of months 1–6 of the terminal phase by the probability of death within 1–6 months among patients who survived each month.

The per patient per month (PPPM) total, inpatient, outpatient, ED, and prescription costs were calculated for each phase of care using the total censoring adjusted costs. Generalized linear models (GLMs) with a gamma distribution and log link function accounting for clustering within matched case-control pairs were used to estimate the adjusted mean PPPM phase-specific health care costs for cases and controls, as well as the difference in the mean phase-specific costs between cases and controls.

Results

The analytic cohort included 1,002 cervical cancer patients matched with 4,005 non-cancer controls and 5,003 endometrial cancer patients matched with 19,999 non-cancer controls. Cases and controls were well balanced in terms of baseline characteristics (age, region, insurance type, and CCI score) after propensity score matching as indicated by an absolute standardized difference <20% ().

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of matched newly diagnosed cancer patients and non-cancer controls.

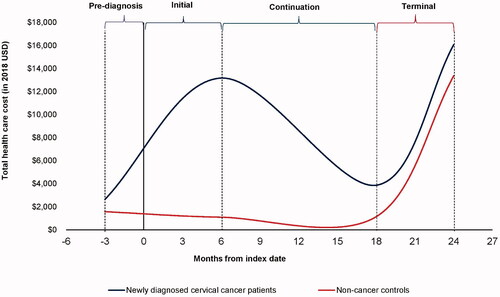

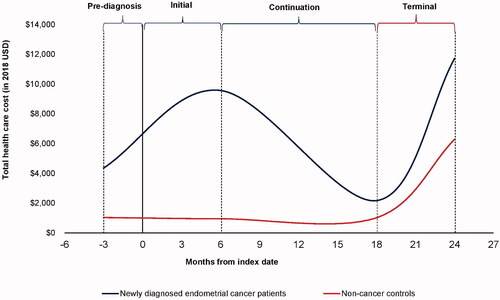

The results of the unadjusted analysis comparing costs for each phase of care between the cancer cases and the matched non-cancer controls are presented in . Mean PPPM costs among cervical and endometrial cancer patients followed a U-shaped pattern in all post-diagnosis phases, with inflection points observed at 6 months post-diagnosis and 6 months before death (). The inflection points in the mean PPPM total costs observed during the initial (6 months post-diagnosis) and terminal (6-months before death) phases among cancer patients suggest that the lengths of the phases of care used in our analysis were appropriate. Costs were high in the initial phase and decreased considerably in the continuation phase before increasing sharply again in the terminal phase.

Table 2. Mean per patient per month unadjusted health care costs among cervical cancer patients and non-cancer controls.

Table 3. Mean per patient per month unadjusted health care costs among endometrial cancer patients and non-cancer controls.

Results from the adjusted analyses for assessing the incremental lifetime, phase-specific, and cost driver (inpatient, outpatient, prescription drug, and other) costs within each phase stratified on matched pairs are presented in . The mean incremental PPPM costs among cervical and endometrial cancer patients across the phases of care were as follows: pre-diagnosis (cervical: $1,057; endometrial: $3,315), initial (cervical: $12,084; endometrial: $8,618), continuation (cervical: $2,732; endometrial: $1,147), and terminal (cervical: $2,702; endometrial: $5,442). The mean adjusted incremental PPPM lifetime costs (95% CI) for cervical cancer and endometrial cancer cases were $5,910 ($5,373–$6,446) and $3,475 ($3,259–$3,691), respectively. Incremental costs were significantly higher for cancer patients vs. non-cancer controls across a patient lifetime and all phases of care (except terminal phase costs for cervical cancer).

Table 4. Mean per patient per month adjusted health care costs among cervical cancer patients and non-cancer controls.

Table 5. Mean per patient per month adjusted health care costs among endometrial cancer patients and non-cancer controls.

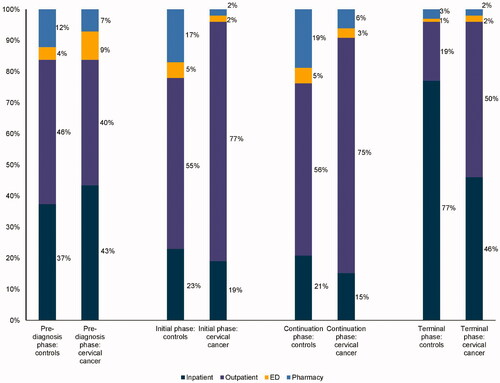

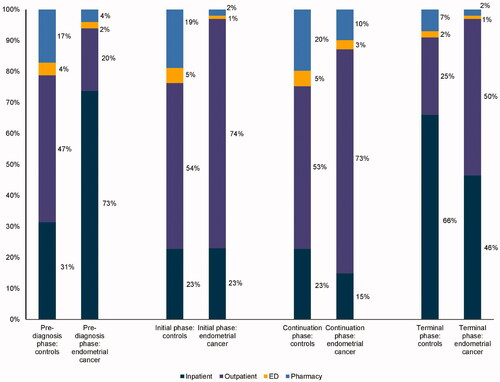

Among cervical and endometrial cancer patients, inpatient costs were the primary drivers of total costs in the pre-diagnosis phase (>40%), while outpatient costs were the major driver of total costs for all post-diagnosis phases (initial phase: >70%; continuation phase: >70%; terminal phase: 50%) ().

Discussion

In the current study, we used a phase-based approach to estimate the incremental costs associated with cervical and endometrial cancer over patients’ lifetimes and for each phase of care (pre-diagnosis, initial, continuing care, and terminal). To our knowledge, this is the first US-based study to estimate the cost burden of cervical and endometrial cancer in a commercially insured patient population. Our findings show that cervical and endometrial cancer patients had a higher mean PPPM total (all-cause) cost compared with non-cancer controls across all phases of care. Incremental costs were also significantly higher for cervical cancer patients vs. non-cancer controls in the pre-diagnosis, initial, and continuation phases of care. Lastly, our results show that cervical cancer patients had the highest mean PPPM total (all-cause) costs during the initial and terminal phases of care.

Previous studies have estimated the longitudinal accumulation of health care costs among cervical and endometrial cancer by phase of care. For example, a 2008 study by Yabroff et al. conducted using 1999–2003 SEER-Medicare data reported that the incremental costs for treating cervical and endometrial cancer were highest during the terminal phase (final 12 months of life), followed by the initial phase (first 12 months after diagnosis) and continuation (months between the initial phase and the last year of life) phases of careCitation5. The incremental costs reported by Yabroff et al. were as follows: initial (cervical: $26,302; endometrial: $16,268), continuation (cervical: $831; endometrial: $916), and terminal (cervical: $28,264; endometrial: $24,651). Differences in the phase-specific costs between those obtained from our analysis and those estimated by Yabroff et al. are likely due to the number of months used to define the initial and terminal phases of care, as well as differences in the study populations. Furthermore, it is important to note that Yabroff et al. conducted their analyses using the 1999–2003 SEER-Medicare data. Thus, it may not be entirely appropriate to compare the magnitude of the phase-specific estimates obtained from Yabroff et al. with those of our study since there has been a change in the treatment landscape for gynecological cancers in the US since 2003.

Subsequent studies have also summarized phase-specific costs of gynecological cancers in non-US settings. For example, a study conducted by Liu et al. summarized the health care costs accrued by newly diagnosed cervical cancer patients in a public payer Canadian settingCitation6. The authors defined the phases of care as pre-diagnosis (1 year before the index date), initial (index date to 1 year after), continuing (1 year after index date to 1 year before death), and terminal (the last year of life) phases of care. Liu et al. reported that cervical cancer patients had a higher mean total health care cost compared with non-cancer controls across all phases of care. The mean total phase-specific costs among cervical cancer patients were reported as follows: pre-diagnosis ($3,155), initial ($17,938), continuing ($6,429), and terminal ($58,319). Contrary to the findings reported in other cancer studies, the authors reported that the total incremental health care costs of cervical cancer compared with non-cancer controls were the highest in the terminal phase of care, followed by the continuation and initial phases of careCitation6. The total incremental costs reported by Liu et al. were significantly higher for cancer patients compared with non-cancer controls across all phases of care. The cost trends reported by Liu et al. were consistent with the trends observed in our study. Differences in the magnitude of the phase-specific estimates between those obtained from our analysis and those estimated by Liu et al. are likely due to the differences between the health care systems in the US and Canada.

Our findings show that following cervical and endometrial diagnosis, cost trends followed a U-shaped curve indicating the higher costs seen in the initial phase, decreased costs in the continuing care phase, and then increased costs again in the terminal phase (). Outpatient costs were the major driver of costs in all phases of care post-diagnosis. Inpatient costs also accounted for a considerable percentage (46%) of the total costs in the terminal phase of care.

The cost trends observed in our analysis can be explained by the treatments recommended for cervical and endometrial cancer patients by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Treatments recommended for early-stage cervical and endometrial cancer patients, including surgery and radiation therapy given with or without chemotherapy, can account for the high total costs observed in the initial phase of careCitation24,Citation25. A recently published study by Blanco et al. examining the cost of care during the first year after a diagnosis of cervical cancer showed significant health care costs among patients treated primarily with surgery and radiationCitation26. The authors further reported that outpatient services accounted for the majority of the median total expenditure among cervical cancer patients treated primarily with surgery. The findings of Blanco et al. suggest that common treatments recommended for early-stage cervical and endometrial cancer patients are associated with high costs, with outpatient services driving total health care costs.

In the continuation phase of care, cervical and endometrial cancer patients can receive systemic chemotherapy or immunotherapy, which are mainly administered at outpatient infusion clinicsCitation24,Citation25. Thus, outpatient costs would be expected to drive total health care costs in the continuation phase of care. Finally, the terminal phase of care among cancer patients can include costs for intensive care services, aggressive chemotherapy or immunotherapy, and palliative end-of-life care, all of which are recommended for patients with advanced diseaseCitation24,Citation25. Treatment approaches for cervical and endometrial cancer patients with the advanced or metastatic disease include chemotherapies or immunotherapies given alone or in combination with radiation therapy. A retrospective analysis by Chastek et al. examined the end-of-life costs among commercially insured oncology patients. The authors reported high total cancer-related costs, with inpatient and outpatient care accounting for 55% and 41% of total costs, respectivelyCitation27.

Our study has several strengths. First, this is the first study to comprehensively describe how health care costs vary among commercially insured cervical and endometrial cancer patients across each phase of care. Second, our analysis is the first to provide lifetime cost estimates for commercially insured newly diagnosed cervical and endometrial cancer patients that account for patient survival in each phase of care. Third, the results of this real-world study are generalizable to commercially insured cervical and endometrial cancer patients and Medicare beneficiaries with commercial coverage. Therefore, the cost estimates from this study can be used as inputs in future cost-effectiveness analyses to project the impact of key interventions as patients progress from one health state to another and can be used by payers to guide resource allocation.

Despite the strengths mentioned above, the study has some limitations. First, the use of diagnosis and procedure codes to identify patients may not accurately capture all required information. Claims databases are always subject to coding errors as these data were collected for the purposes of reimbursement and not research. Second, some clinical variables of interest are not available in claims databases, including Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scores, cancer stage, grade, and tumor size. In the absence of such clinical covariates in the database, study findings are subject to the unobserved confounding that is inherent to observational studies. Moreover, it is not possible to link the phases of care with the disease stage. Third, the mortality information linked to the Optum claims dataset is provided by the SSA and is subject to missing data. This is a key limitation because only 5% of the patients in this study reached the terminal phase of care. Fourth, while analytic methods such as propensity matching have been used to minimize the impact of selection bias and observed confounding, study findings are subject to residual confounding. Fifth, while we aimed to achieve a perfect match for all 1,002 cervical cancer patients and 5,003 endometrial cancer patients, the nearest neighbor greedy matching algorithm used in our analysis was unable to find 4 non-cancer controls for some cancer patients. Sixth, the database does not capture a patient’s health care resource use outside of the plans included in Optum data, which may have resulted in underestimating costs. Lastly, the results observed in this analysis may not be generalizable to uninsured patients, Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries, and patients covered by Medicaid.

Conclusions

This study highlights the substantial economic burden associated with a cervical and endometrial cancer diagnosis and care. Findings on the economic burden of these cancers, including the lifetime and phase-specific cost burden, and the drivers of cost in each phase of care can aid policy makers’ discussions regarding resource allocation and treatment reimbursement.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This research was funded by Merck & Co., Inc.

Declaration of financial/other interests

R.S., S.C., A.S., and N.K. are employees of Open Health Evidence and Access, which received research funding from Merck & Co., Inc. for this study. C.N. is an employee of Merck & Co., Inc. and owns Merck and Co. stock.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

R.S., S.C., A.S., N.K., and C.N. designed the study. R.S., S.C, A.S., N.K., and C.N. interpreted the study results and drafted the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the copy-editing services provided by Christina DuVernay, Ph.D., of Open Health Evidence and Access.

References

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2019. Atlanta (GA): American Cancer Society; 2019.

- Funke M, Goyal G, Silberstein PT. Demographic and insurance-based disparities in diagnosis of stage IV cervical cancer: a population-based analysis using NCDB. Alexandria (VA): American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2015.

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer stat facts: cervix uteri cancer. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute; 2018.

- National Cancer Institute: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: uterine cancer; 2019.

- Yabroff KR, Lamont EB, Mariotto A, et al. Cost of care for elderly cancer patients in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(9):630–641.

- Liu N, Mittmann N, Coyte PC, et al. Phase-specific healthcare costs of cervical cancer: estimates from a population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(5):615.e1–615.e11.

- de Oliveira C, Pataky R, Bremner KE, et al. Phase-specific and lifetime costs of cancer care in Ontario, Canada. BMC Cancer. 2016;16(1):809.

- Aly A, Johnson C, Doleh Y, et al. The real-world lifetime economic burden of urothelial carcinoma by stage at diagnosis. J Clin Pathways. 2020;6(4):51–60.

- Deshmukh AA, Zhao H, Franzini L, et al. Total lifetime and cancer-related costs for elderly patients diagnosed with anal cancer in the United States. Am J Clin Oncol. 2018;41(2):121–127.

- D'Hoore W, Bouckaert A, Tilquin C. Practical considerations on the use of the Charlson Comorbidity Index with administrative data bases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(12):1429–1433.

- Shah D, Allen L, Zheng W, et al. Economic burden of treatment-resistant depression among adults with chronic non-cancer pain conditions and major depressive disorder in the US. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39(6):639–613.

- Zhao X, Bhattacharjee S, Innes KE, et al. The impact of telemental health use on healthcare costs among commercially insured adults with mental health conditions. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36(9):1541–1548.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index (CPI) Databases; 2019. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

- Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399–424.

- Hornbrook MC, Fishman PA, Ritzwoller DP, et al. When does an episode of care for cancer begin? Med Care. 2013;51(4):324–329.

- Christensen KG, Fenger-Grøn M, Flarup KR, et al. Use of general practice, diagnostic investigations and hospital services before and after cancer diagnosis—a population-based nationwide registry study of 127,000 incident adult cancer patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):224–228.

- Taplin SH, Barlow W, Urban N, et al. Stage, age, comorbidity, and direct costs of colon, prostate, and breast cancer care. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87(6):417–426.

- Seidler AM, Pennie ML, Veledar E, et al. Economic burden of melanoma in the elderly population: population-based analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare data. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(3):249–256.

- Yabroff KR, Warren JL, Brown ML. Costs of cancer care in the USA: a descriptive review. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4(11):643–656.

- Aly A, Clancy Z, Ung B, et al. Drivers of phase-based costs in patients with multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(15_suppl):e20022.

- Bhattacharya K, Bentley JP, Ramachandran S, et al. Phase-specific and lifetime costs of multiple myeloma among older adults in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2116357.

- Surveillance Research Program NCI. SEER* Explorer: An interactive website for SEER cancer statistics; 2019. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/explorer/

- Arias E. United States life tables, 2017. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019;68(7):1–66.

- Koh W-J, Abu-Rustum NR, Bean S, et al. Cervical cancer, version 3.2019. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(1):64–84.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Uterine neoplasms (version 3.2019); 2019. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/uterine.pdf

- Blanco M, Chen L, Melamed A, et al. Cost of care for the initial management of cervical cancer in women with commercial insurance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;224:286.e1–286.e11.

- Chastek B, Harley C, Kallich J, et al. Health care costs for patients with cancer at the end of life. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8(6):75s–80s.