?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Objectives

To demonstrate how medical purchasing power parities (mPPP) may harmonize economic evaluations from different jurisdictions and enable comparisons across jurisdictions.

Methods

We describe the use of mPPPs and illustrate this with an example of economic evaluations of nab-paclitaxel with gemcitabine (Nab-P + Gem) versus gemcitabine monotherapy in the setting of metastatic pancreatic cancer. Following a literature search, we extracted data from cost-effectiveness studies on these treatments performed in various countries. mPPPs from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development were used to convert reported costs in the jurisdiction of origins to US dollars for the most current year using two possible pathways: (1) reported costs first adjusted by mPPP then adjusted by exchange index; and (2) reported costs first adjusted by exchange index then adjusted by mPPP.

Results

Despite many of the pharmaco-economic evaluations sharing similar assumptions and inputs, even after mPPP conversion, residual heterogeneity was attributable to perspectives, discount rate, outcomes, and costs, among others; including in studies conducted in the same jurisdiction.

Conclusion

Despite the methodological challenges and heterogeneity within and across jurisdictions, we demonstrated that mPPP offers a way to compare economic evaluations across jurisdictions.

Introduction

With healthcare delivery and financing systems differing around the world, it is challenging to compare pharmacoeconomic evaluations for the same treatments across jurisdictions, whether these are countries, within-country jurisdictions (states, provinces, etc.), or transnational organizationsCitation1. In addition to differences in healthcare infrastructures, other factors contribute to this challenge, including incidence and severity of disease, clinical practice guidelines, healthcare resources, and pricesCitation1. Further, pharmacoeconomic evaluations may differ across jurisdictions in the type of models used; analyses applied; inputs; prevailing legal and regulatory aspects; and payment mechanisms. Unsurprisingly, pharmacoeconomic evaluations of the same treatment may differ in their results within and between jurisdictions. Differences up to a fourfold have been reported when comparing estimates on the basis of (unadjusted) foreign exchange ratesCitation2,Citation3. There are, however, compelling reasons for order-of-magnitude comparisons across countries, such as ensuring the reliability and validity of the outcomes among jurisdictions where healthcare systems are similar and understanding how different healthcare systems can affect these outcomes.

Major textbooks offer limited technical guidance on comparing pharmacoeconomic studies in different jurisdictionsCitation4–7. A Good Practices Task Force of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) offers guidance that is limited to the transferability of cost-effectiveness results across jurisdictionsCitation8. In this guidance, the Task Force focused on how to assess whether existing pharmaco-economic evaluation data from jurisdiction A can be applied to the new jurisdiction B, or whether a local economic evaluation must be conducted in jurisdiction B. The Task Force did not provide guidance on how to harmonize economic evaluation results across jurisdictions as the basis for a comparison of, say, cost-effectiveness or cost-utility analysesCitation8.

Notably, the ISPOR Task Force did mention using purchasing power parities (PPP) for adjusting costs but provided no further direction as to the procedures. In this Technical Note, we introduce the concepts of PPP and medical PPP (mPPP) and describe how to calculate these metrics. We further apply this to the case of cost-effectiveness studies comparing the regimen of albumin-bound paclitaxel plus gemcitabine (Nab-P + Gem) to gemcitabine monotherapy (GEM) in the treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer across different jurisdictions.

The concepts of PPP and mPPP

From an application perspective, PPPs aim to equalize purchasing power in situations where either cost, currency, or both are different. For our discussion, PPPs are defined as adjusted currency conversion rates that equalize the purchasing power of different currencies across jurisdictions by estimating, for a particular good or service (“product”), the ratio of the cost in one jurisdiction to the cost in another jurisdiction, each price expressed in its local currencyCitation9; or in its simplest formCitation10,

where X refers to the good or service of interest (hereafter “product”).

PPPs are price relatives that can be estimated at three levels. First, at the product level, it involves calculating price relatives for an individual product, where price relative is the ratio of one price of a given product to another price of the same productCitation11,Citation12. This level enables by-product comparisons between jurisdictions. Next, at the product group level, an individual product is grouped with other similar products into a product basket. The PPPs for each product are averaged, yielding an unweighted PPP for the group. This is of interest when, for instance, the cost of a class of products needs to be compared across jurisdictions. Lastly, at the aggregation level, the PPPs of various but related product groups are put into an aggregate basket. The PPPs are weighted based on their jurisdictions’ expenditures on the products, and a weighted average is calculated yielding an aggregate PPP.

For example, if one were to estimate PPPs for antihypertensive agents, the product level would comprise all approved antihypertensive agents, and a PPP would be calculated for each. At, the product group level, these agents could be classified on the basis of their mechanism of action: thiazide diuretics, adrenergic receptor antagonists, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists (ARB), and renin inhibitors. At the aggregate level, all agents would be rolled up into the aggregate of “Antihypertensive Agents”.

In this Technical Note, we define mPPPs as PPPs related to healthcare products and servicesCitation9,Citation11. Yearly, the OECD provides mPPPs using the US dollar (US$) as a base and expressing each country’s health economic data in US$PPPs: (1) current expenditure on health, per capita, US$PPP; (2) government and compulsory health insurance schemes expenditures, per capita, US$PPP; (3) out-of-pocket expenditure, per capita, US$PPP; and (4) current expenditure on pharmaceuticals and other medical non-durables, per capita, US$PPPCitation13. The mPPPs are reported annually and depending on the availability of data, OECD provides mPPPs to the most recent year. In the 2021 OECD Health, the most recent year for which mPPPs were reported was 2019. However, as 2019 and, to some extent, 2018 data, were still incomplete for some countries or some variables, the most recent year reported may have been 2018 or 2017Citation13.

Application of mPPP

Pancreatic cancer is the seventh leading cause of cancer deaths in industrialized countriesCitation14 and one of the major causes for cancer deaths in Europe and the USCitation15. Until the 2013 FDA approval of albumin-bound paclitaxel (nab-paclitaxel; Abraxane, Bristol Myers Squibb, New York, NY) as conjunctive therapy with gemcitabine, gemcitabine was the first-line therapy for 15 yearsCitation16–18, with FOLFIRINOX as a third optionCitation17. In the pivotal trialCitation19, the combination of Nab-P + Gem showed improvements in overall survival, progression-free survival, and response rateCitation19.

Regulatory approvals of nab-paclitaxel as conjunctive therapy in US and subsequently in other jurisdictions was followed by economic evaluations in many markets, often in support of payer and formulary listings. In turn, this raised the question as to how to compare these economic analyses across borders, healthcare delivery systems, and healthcare financing systems. In the independent exercise reported here, we propose to align pharmacoeconomic assessments of Nab-P + Gem by using the mPPP as the preferred approach.

Methods

We searched the Cochrane, PubMed, and EMBASE databases for full reports of economic evaluations of Nab-P + Gem from 2013 to 2021 using the keywords “pancreatic cancer”, “economic evaluation”, “gemcitabine”, and “nab-paclitaxel”, as well as variations of these to ensure a complete search. We extracted from each report, as available, the country, currency, year of costs, treatment regimens, costs of regimens, outcomes, discount rate, perspective, model, and funding source.

Since OECD reports mPPPs based on the availability of data, we defined the nearest reported year as the most recent year of mPPPs provided. For example, we utilized 2018 mPPP value for the US evaluations and 2019 mPPP for the Canadian studyCitation20. Inflation or deflation rates were not adjusted to these final values as we were more interested in utilizing mPPPs as an enabling factor for comparisons of economic studies.

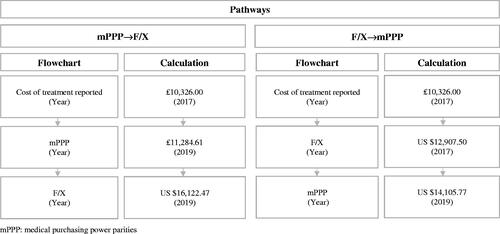

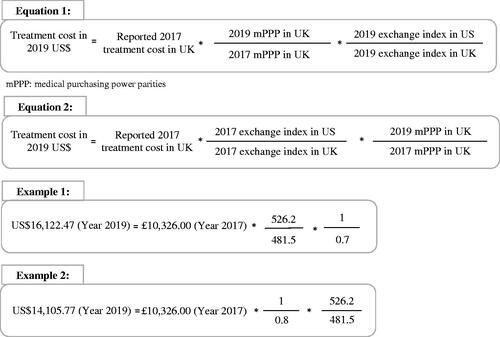

As illustrated in and , to calculate the updated costs to the nearest reported year of mPPPs, we used the reported cost data including the year of report, mPPPs, and currency exchange costs. We specified two pathways.

Figure 1. Flowcharts of pathways with application to estimating the cost of gemcitabine using the Gharaibeh 2018 UK study as a basis.

Figure 2. Equations for converting costs to 2019 US$ for both pathways with application to estimating the cost of gemcitabine using the Gharaibeh 2018 UK study as a basis.

In the first pathway, the reported costs are first adjusted to US$ on the basis of the ratio of the mPPP for the target year to the mPPP for the original year of estimation in the jurisdiction of origin. This estimate is subsequently adjusted on the basis of the ratio of the exchange index in the target jurisdiction to the exchange index in the jurisdiction of origin and this for the target year. Let C(Jt,Yt) denote the cost in the target jurisdiction Jt for the target year Yt; C(Jo,Ye) the cost in the jurisdiction of origin Jo in the original year of estimation Ye; mPPP(Jo,Yt) the mPPP in the jurisdiction of origin Jo for the target year Yt; mPPP(Jo,Ye) the mPPP in the jurisdiction of origin Jo, in the original year of estimation Ye; EI(Jt,Yt) the exchange index in the target jurisdiction Jt for the target year Yt; and EI(Jo,Yt) the exchange index in the jurisdiction of origin Jo for the target year Yt. Then,

(1)

Conversely, in the second pathway, the reported costs are first adjusted to US$ on the basis of the ratio of the exchange index in the target jurisdiction to the exchange index in the jurisdiction of origin and this for the original year of cost estimation; followed by the ratio of the mPPP for the target year to the mPPP for the original year of estimation in the jurisdiction of origin. Analogously to EquationEquation (1)(1) , let C(Jt,Yt) denote the cost in the target jurisdiction Jt for the target year Yt; C(Jo,Ye) the cost in the jurisdiction of origin Jo in the original year of estimation Ye; EI(Jt,Ye) the exchange index in the target jurisdiction for the original year of estimation; EI(Jo,Ye) the exchange index in the jurisdiction of origin Jo for original year of estimation; mPPP(Jo,Yt) the mPPP in the jurisdiction of origin Jo for the target year Yt; and mPPP(Jo,Ye) the mPPP in the jurisdiction of origin Jo, in the original year of estimation Ye. Then,

(2)

In the application shown in and , the mPPP inputs were sourced from the OECD and the currency exchange inputs from the World BankCitation21.

Results

Studies included

As summarized in , we retained 11 studies, including seven from (pre-Brexit) European member countries (three from the UK, and one each from Spain, Greece, Italy, and Slovakia), two from the US, and one each from Canada and JapanCitation2,Citation3,Citation20,Citation22–29. With the exception of the Japanese study, the remaining 10 studies included the outcomes of life years (LY) and quality-adjusted life years (QALY), including nine that reported the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) and/or the incremental cost-utility ratio (ICUR). While the Japanese study could have been excluded because it was markedly different in methodology from the other studies, we retained it nonetheless because the primary focus of the exercise reported here is the calculation of harmonized costs using mPPP. Studies that did not specify the dosing of the regimensCitation2,Citation25,Citation26,Citation29 were assumed to have based their dosing on the pivotal clinical trialCitation19.

Table 1. Overview of studies included.

also summarizes other methodological aspects (discount rate, perspective, model) for informational purposes. Of note, of the eight studies reporting their funding source, three were sponsored by Celgene (before its acquisition by Bristol Myers Squibb), while five were independent studies. As shown in , five studies sourced their treatment cost inputs from official listings, two studies applied data from comprehensive price compilations, while the remainder used less formal sources.

Table 2. Source of cost inputs.

It is evident that studies differed in some key methodological aspects, which is important to point out because this may affect the respective results and possibly induce heterogeneity. This heterogeneity needs to be considered when interpreting the data in and ; specifically, the costs of the treatment regimens (Nab-P + Gem versus Gem) in each jurisdiction, their subsequent mPPP conversion to US$, and the estimated cost differences between both regimens harmonized to US$ (note that these estimates are for nearest year reported).

Table 3. Costs inputs.

Table 4. Cost calculations.

Pathway 1: mPPP→F/X

As shows, converted costs based on the mPPP→F/X pathway ranged widely across countries. For instance, the highest cost for Nab-P + Gem was in the US at (rounded) 2018 US$57,316, while the lowest was 2018 US$14,977 in the UK. However, and despite being the two highest estimates across all studies, the two US estimates differed by only $6,145, compared to the high/low difference of US$34,180 in the three UK studies – underscoring also the within-jurisdiction volatility in estimates attributable to the source of the inputs. Note that the costs of Nab-P + Gem in Japan and Canada were rather closely aligned with the (still higher) cost of this regimen in the US. Regarding the costs of the Gem regimen – and considering that Gem is competitively available in several generic versions – here too the US had the prices at the higher end, US$24,059 and US$23,815 (difference US$244). However, most noteworthy is the high/low difference of US$21,013 for the UK, which raises questions about the inputs used in the Strainthorpe et al. study as this had the highest price of Gem at US$27,200Citation2,Citation3,Citation20,Citation22–29.

Pathway 2: F/X→mPPP

The costs calculated from the F/X→mPPP also showed wide cost ranges (). However, the highest and lowest costs of treatments and associated cost differences diverged from those obtained from the mPPP→F/X pathway calculations. The highest cost of Nab-P + Gem was in the Stainthorpe et al. study with (rounded) 2019 US$57,353.99 and the lowest was in the Slovakian study with 2019 US$10,878.12. Similarly, for Gem treatment, the UK study done by Stainthorpe et al. had the highest cost (2019 US$31,408.15), while the Slovakian study had the lowest cost (2019 US$4,356.37). The largest difference in costs was similar to the mPPP→F/X result, with Japan having the largest (2019 US$38,019.38) and Slovakia having the smallest cost difference (2019 US$6,521.75)Citation2,Citation3,Citation20,Citation22–29.

Difference in mPPP→F/X and F/X→mPPP

In general, the calculated costs and cost differences were similar for both pathways. Larger discrepancies were seen in countries whose exchange rates varied significantly between the original year of estimation and the target year. The calculated costs remained approximately the same for countries with stable exchange rates over the period of interestCitation2,Citation3,Citation20,Citation22–29.

Comments

Although the same concept of mPPP and currency exchange indexes were applied in both calculation pathways, cost estimates varied based on the calculation pathway. Because of this, it is important to understand when to use each pathway. The mPPP→F/X pathway may be preferred if estimates in present day value are required. Conversely, by adjusting for exchange rate at the time that the initial costs are estimated and subsequently using this currency-adjusted estimate to extrapolate to present day purchasing power, the F/X→mPPP pathway is indicated in the case of stable currency exchange rates or when the focus is on evaluating mPPP growth rates following an initial currency adjustment.

As a caution, mPPP-based conversion enables empirical comparisons of cost estimates of treatments for a given health condition across jurisdictions, however it does not guarantee that the estimates are comparable in methods and inputs. In its recommendations, the ISPOR Good Practices working party emphasized the importance of understanding differentiating factors in economic evaluations of a given jurisdiction when assessing the transferability of a study to other jurisdictionsCitation8. An important element in this is to determine (a) whether a jurisdiction has formalized guidelines and methods for the economic evaluation of health technologies and pharmaceutical products in particular, and (b) the degree to which these guidelines and methods vary from one jurisdiction to the next. We refer to the ISPOR document for further discussion of transferability of economic evaluationsCitation8.

Despite the inherent methodological challenges in directly comparing economic evaluations done in different jurisdictions, utilization of mPPPs can facilitate this process if this is done under consideration of the methods used. If the studies in a set of economic evaluations are conceptually and methodological similar, the mPPP approach offers a reliable way of comparing cost inputs but also such metrics as the ICER and ICUR. However, when study designs are not similar, mPPPs can be utilized only to compare the costs of treatments.

Lastly, focusing on the OECD statistics but generalizable to other data sources as well, not all countries may report their mPPPs for the same year. Consequently, there may be a 1- or 2-year lag for a particular country estimate that may be subjected to inflation of deflation.

Conclusion

Facing the challenges of comparing pharmaco-economic studies and extending prior recommendations regarding the transferability of economic evaluations across jurisdictions, we demonstrated in this Technical Note how to convert cost estimates in various currencies and in different jurisdictions on the basis of mPPPs. The mPPP pathways imply that these estimates, whether inputs or outputs, are conceptually and methodologically similar so that the exercise is one of “comparing comparables” rather than “comparing incomparables”.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study received no funding.

Declaration of financial/other interests

IA holds equity in Matrix45, LLC, which provides research and consulting services to, among others, the pharmaceutical industry. Matrix45, LLC previously was contracted by Celgene for work unrelated to the subject of this Technical Note. By company policy, associates of Matrix45, LLC cannot provide services to nor receive compensation independently from sponsor organizations. IA has no other disclosures related to the work reported herein.

All other authors have no disclosures related to the work reported herein.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

BMC and RBA contributed to study conceptualization, data collection, analyses and interpretation of data, revision, and final approval of the manuscript.

HH, MC, MOK, NA, and DA contributed to analyses of the data, revision, and final approval of the manuscript.

IA contributed to study conceptualization, study design, revision, analyses, and interpretation of data, and final approval of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank an anonymous reviewer for the helpful suggestion to consider a second calculation pathway.

Previous presentations

This study has not been presented previously.

References

- Sculpher MJ, Pang FS, Manca A, et al. Generalisability in economic evaluation studies in healthcare: a review and case studies. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8(49):iii–iv.

- Gharaibeh M, McBride A, Bootman JL, et al. Economic evaluation for the US of nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine versus FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine in the treatment of metastatic pancreas cancer. J Med Econ. 2017;20(4):345–352.

- Kurimoto M, Kimura M, Usami E, et al. Comparing the cost-effectiveness of FOLFIRINOX, nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine, gemcitabine and S-1 for the treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;7(1):125–130.

- Rascati KL. Essentials of pharmacoeconomics. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014.

- Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, et al. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

- Briggs A, Claxton K, Sculpher M. Decision modelling for health economic evaluation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2011.

- Bootman JL. Principles of pharmacoeconomics. Cincinnati, OH: H. Whitney Books; 1999.

- Drummond M, Barbieri M, Cook J, et al. Transferability of economic evaluations across jurisdictions: ISPOR good research practices task force report. Value Health. 2009;12(4):409–418.

- Purchasing power parities – frequently asked questions (faqs) [Internet]. OECD; 2021 [cited 2021 Sep 19]. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/sdd/prices-ppp/purchasingpowerparities-frequentlyaskedquestionsfaqs.htm.

- PPP calculation and estimation [Internet]. World Bank; 2021 [cited 2021 Sep 19]. Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/icp/brief/methodology-calculation.

- Eurostat-OECD methodological manual on purchasing power parities (2012 edition) [Internet]. OECDiLibrary. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2012. [cited 2021 Sep 19]. Available from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/eurostat-oecd-methodological-manual-on-purchasing-power-parities_9789264189232-en.

- Price relative [Internet]. OECD glossary of statistical terms. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; 2007 [cited 2021 Sep 19]. Available from: https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=2111.

- OECD health statistics 2021 [Internet]. OECD; 2021 [cited 2021 Sep 19]. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/health-data.htm.

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424.

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (eds). Seer cancer statistics review, 1975–2018 [Internet]. SEER [cited 2021 Sep 19]. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2018/.

- Conroy T, Bachet JB, Ayav A, et al. Current standards and new innovative approaches for treatment of pancreatic cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2016;57:10–22.

- Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al. Groupe tumeurs digestives of unicancer; PRODIGE intergroup. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(19):1817–1825.

- Saif MW. U.S. Food and Drug Administration approves paclitaxel protein-bound particles (Abraxane®) in combination with gemcitabine as first-line treatment of patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. JOP. 2013;14(6):686–688.

- Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(18):1691–1703.

- Coyle D, Ko YJ, Coyle K, et al. Cost-Effectiveness analysis of systemic therapies in advanced pancreatic cancer in the Canadian health care system. Value Health. 2017;20(4):586–592.

- World development indicators: The World Bank; 2021 [cited 2021 Sep 19]. Available from: http://wdi.worldbank.org/table/4.16.

- Carrato A, García P, López R, et al. Cost-utility analysis of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel (nab-paclitaxel) in combination with gemcitabine in metastatic pancreatic cancer in Spain: results of the PANCOSTABRAX study. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;15(4):579–589.

- Fragoulakis V, Papakostas P, Pentheroudakis G, et al. Economic evaluation of NAB-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine alone for the management of metastatic pancreatic cancer in Greece. Value Health. 2014;17(7):A632.

- Gharaibeh M, McBride A, Bootman JL, et al. Economic evaluation for the UK of nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine in the treatment of metastatic pancreas cancer. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(8):1301–1305.

- Gharaibeh M, McBride A, Alberts DS, et al. Economic evaluation for the UK of systemic chemotherapies as first-line treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(11):1333–1343.

- Gharaibeh M, McBride A, Alberts DS, et al. Economic evaluation for USA of systemic chemotherapies as first-line treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(10):1273–1284.

- Lazzaro C, Barone C, Caprioni F, et al. An italian cost-effectiveness analysis of paclitaxel albumin (nab-paclitaxel) + gemcitabine vs gemcitabine alone for metastatic pancreatic cancer patients: the APICE study. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;18(4):435–446.

- Stainthorpe A, Greenhalgh J, Bagust A, et al. Paclitaxel as Albumin-Bound nanoparticles with gemcitabine for untreated metastatic pancreatic cancer: an evidence review group perspective of a NICE single technology appraisal. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(10):1153–1163.

- Stetka R, Ondrusova M, Psenkova M, et al. A Cost-Utility analysis of Nab-Paclitaxel (abraxane) plus gemcitabine in metastatic pancreatic cancer in Slovak Republic. Value in Health. 2015;18(7):A464.