Abstract

Aim

To evaluate the cost utility of adjunct racecadotril and oral rehydration solution (R + ORS) versus oral rehydration solution (ORS) alone for the treatment of diarrhoea in children under five years with acute watery diarrhoea in four low-middle income countries.

Method

A cost utility model, previously developed and independently validated, has been adapted to Egypt, Morocco, Philippines and Vietnam. The model is a decision tree, cohort model programmed in Microsoft Excel. The model structure represents the country-specific clinical pathways. The target population is children under the age of five years presenting with symptoms of acute watery diarrhea to an outpatient clinic or general physician practice. A healthcare payer perspective has been analysed with the model parameterised with local data, where available. Most recent cost data has been used to inform the drug, outpatient and inpatient costs. Uncertainty has been explored with univariate deterministic sensitivity.

Results

According to the base case models, R + ORS is dominant (cost-saving, more effective) versus ORS alone in Egypt, Morocco, Philippines and Vietnam. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratios in each country fall in the southeast (cost-saving, more effective) quadrant and represent a cost savings of −304,152 EGP per QALY gain in Egypt; −6,561 MAD per QALY gain in Morocco; −428,612 PHP per QALY gain in Philippines and −113,985,734 VND per QALY gain in Vietnam. Univariate deterministic sensitivity analysis shows that the three most influential parameters across all country adaptations are the utility of children without diarrhea; the utility of inpatient children with diarrhea and the cost of one night of inpatient care.

Conclusion

In keeping with similar findings in upper-middle and high-income countries, the cost utility of R + ORS versus ORS is favourable in low-middle income countries for the treatment of children under five with acute watery diarrhoea.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Decision-makers rely on cost utility models to inform decisions about whether to publicly fund treatments as part of Universal Health Care. In low-middle income countries, the capacity to prepare cost utility models may be limited and using existing validated models is a practical solution to assist decision making. This study uses a cost utility model developed and independently validated for the United Kingdom, and adapts it to Philippines, Egypt, Morocco and Vietnam. The model evaluates the clinical benefit and economic impact of using racecadotril in addition to rehydration solution to treat diarrhoea in children. The results show that racecadotril is cost-saving and improves the quality of life for children in Philippines, Egypt, Morocco and Vietnam.

Introduction

Diarrhea continues to be a public health priority in low middle-income countries (LMIC) and remains among the top ten causes of death in children under five in Egypt, Morocco, Philippines and VietnamCitation1. The under-five mortality rate (deaths per 1,000 live births) due to diarrhea has decreased from 86 to 20 in Egypt, 57 to 27 in Philippines, 79 to 21 in Morocco and 51 to 20 in Vietnam between 1990 and 2019Citation2. In spite of these reductions in mortality, the morbidity of diarrhea is a significant burden on public health servicesCitation3–7. According to the World Bank, the percentage of children who received ORS for diarrhea was 28% in Egypt (2014); 22% in Morocco (2011), 44% in Philippines (2017) and Vietnam 50% in Vietnam (2014) Citation8. Assuming constant percentage, a crude calculation based on the latest available population estimates would mean an excess of 340 million children in Egypt, 85 million in Morocco, 514 million in Philippines and 394 million in Vietnam treated for childhood diarrhoea in one yearCitation9–11.

Children with diarrhea commonly present in polyclinics, outpatient clinics and general practitioner settingsCitation12–16. If there is evidence of dehydration, they are referred for inpatient careCitation12–15,Citation17,Citation18. This places a substantial burden on already constrained health care services and although there is no direct evidence from the countries in focus, the economic burden of diarrhea in LMIC is widely establishedCitation4–6,Citation19–22.

Publicly funded treatment options are available via National Formularies and Essential Medicines Lists. The decision to list treatment, in turn, depends on decision-making processes using health technology assessment (HTA). Egypt, Morocco, Philippines and Vietnam are at different stages of adoption of HTA. The Philippines is leading the way, in 2019 the Philippines Universal Healthcare Act institutionalized HTA as a priority-setting mechanism to provide a recommendation to the DOH and PhilHealth for the development of medical intervention policiesCitation23. In 2020 the HTA Unit, Department of Health, Republic of Philippines released the first edition of the Methodological standards in the evaluation of health technologies in the Philippines in which they refer to the ‘reference case’Citation23. Egypt is following and is currently integrating HTA processes into decision-making. Morocco and Vietnam appear to be in the preliminary phases of moving towards the use of HTA for decision makingCitation1,Citation24–33. In Morocco, HTA is currently not mandatory and therefore relies on the Essential Medicines List of the World Health Organisation to guide treatment. It is noted that the Philippines and Vietnam are listed as being part of the International Decision Support InitiativeCitation34. For countries in the early stages of HTA with limited local capacity, leveraging on existing evidence and expertise is advantageousCitation35. To this end, health economic model adaptations are a pragmatic and widely accepted way of achieving thisCitation36–38.

Racecadotril is an oral enkephalinase inhibitor used for the treatment of acute diarrhoea and authorised by the European Medicines AgencyCitation39,Citation40. To date, no study has been done to evaluate the cost utility of racecadotril for the treatment of children with diarrhea in LMIC, although several studies have been published for high-income and upper-middle-income countriesCitation41–43. In view of the persistent challenge of diarrhoea, the growing importance of HTA in the countries in focus and the acceptability of leveraging on existing economic evaluations, this study has been undertaken. The objective is to evaluate R + ORS versus ORS alone in children under the age of five with acute watery diarrhoea in Egypt, Morocco, Philippines and Vietnam to support emerging HTA processes and inform public health funding bodies at country level.

Methods

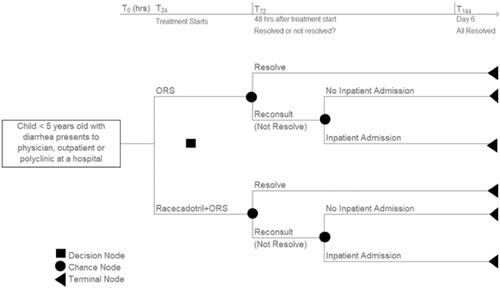

A core model developed for a high-income country and adapted to two upper-middle-income countries has been previously publishedCitation41–43. This study adapts the model to local country settings in Egypt, Morocco, Philippines, and Vietnam. The pre-specified decision problem for each country is to determine the cost utility (cost per quality-adjusted life-year) of the intervention R + ORS versus the comparator ORS alone. The intervention Racecadotril is currently licensed and reimbursed in many countries worldwide but is not publicly funded in Egypt, Morocco, Philippines, and VietnamCitation40. The comparator is ORS alone, the recommended treatment according to international and national guidelinesCitation12–15,Citation17,Citation18. A publicly-funded healthcare payer perspective is adopted in line with the Philippines HTA guideline which requires a government payor perspective, the Egypt guideline which requires the perspective of the health care system, and the International Decision Support Initiative which requires direct health costs and outcomes for countries with no local guidelinesCitation23,Citation24,Citation34. The target population is children under the age of five years presenting with symptoms of acute watery diarrhea to an outpatient clinic or general physician practice. The model schematic has been previously published and is reproduced with permission from the original publisher, Dove Medical Press as Citation41.

Figure 1. Model schematic reproduced with permission from Dove Medical Press. Rautenberg et al. Citation41.

The model structure represents the following clinical situation: children present to an outpatient facility or general physician’s (GP) office with diarrhea and use ORS alone versus R + ORS as the first treatment option. If diarrhea persists, the assumption is that the child re-presents and at this stage may have clinical signs of dehydration. If no signs of dehydration, the child is assumed to be treated under outpatient/GP care. If there are clinical signs of dehydration then a proportion of children are referred to an inpatient hospital setting.

Four key sets of parameters capture the clinical effects in the core model and are retained in the country adaptations. The first set of parameters relates to the proportion of patients whose diarrhea resolves/does not resolve within 48 h of starting ORS or R + ORS. It is a synthesis-based estimate from a meta-analysis by Lehert et al. using nine studies from countries including Peru, India, Mexico and Guatemala that have similarities to the healthcare system in LMICCitation44. It shows that twice as many patients recover at any time with R + ORS: hazard ratio 2.04 (95% CI: 1.85–2.32; p < .001) Citation44. Based on the meta-analysis, diarrhea resolves at 48 h in 26% of ORS and 58% of R + ORS childrenCitation41,Citation44. The second set of parameters relates to the proportion of patients on ORS versus R + ORS referred for inpatient care at second consultation (48 h). This parameter is retained from the core model and is from a clinical study done in Spain to evaluate secondary referral at 48 h in 148 children aged 3–36 months with acute gastroenteritisCitation45. The study reported that 36% on ORS alone versus 6% on R + ORS had secondary referralCitation45. The third set is the proportion of children experiencing adverse events for ORS and R + ORS. In the core model, the data informing the adverse events comes from individual case safety reports (ICSR) and clinical trials between March 1993 and March 2009Citation46. In total there were 94 ICSR from 34 countries reporting 94 ICSRs (144 adverse events) among 26.12 million patients, a frequency of approximately one for every 278,000 patientsCitation46. According to Baumer et al. 16% of ORS and 12% of R + ORS patients experienced adverse eventsCitation46. The frequency of vomiting is 5.1% versus 5.8%; fever 2.3% versus 4.6% and other allergic reactions 1.3% versus 1.4% for R + ORS and ORS alone respectivelyCitation46. The fourth is the utility of children with diarrhea in a primary care (0.7345) and secondary care (0.6145) setting and is taken from a study by Martin et al. which measured quality of life in children with acute infectious gastroenteritis rated by general physicians and paediatricians in the United Kingdom. The utility of a well-child is based on the utility of a well adult (0.94) Citation47,Citation48. The reader is referred to a full description and justification of the clinical evidence used in the core model and retained in the adaptationsCitation41. For convenience, the parameters are summarised in Supplementary Material Table 1.

Table 1. Cost parameters for Egypt, Morocco, Philippines and Vietnam (local currency).

No differential mortality is expected (conservative approach) therefore the time horizon of six days has been used which is sufficiently long to capture all relevant differences in costs and outcomesCitation41. Due to the short time horizon, no discounting is applied to costs or outcomes. No subgroup analysis has been undertaken. Resource use is estimated and valued according to local country cost data shown in . The latest available cost data has been used to inform the drug, ORS, inpatient and outpatient cost. All other aspects of the model have been previously describedCitation41–43. A deterministic univariate sensitivity analysis has been undertaken. In all country adaptations, cost data is inputted in the local country currency shown in .

Results

According to the model pathways shown in , in a cohort of 100 children who present to the outpatient setting and start treatment with ORS alone, diarrhea will resolve in 26 children 48 h after receiving ORS alone and not resolve in 74 children who will be followed up as outpatients. Of these 74, 36 will be referred for inpatient care while 64 will remain in outpatient care. In comparison, in a cohort of 100 children who present to the outpatient setting and start treatment with R + ORS, diarrhea will resolve in 58 children 48 h after receiving R + ORS and not resolve in 42 children and will be followed up as outpatients. Of these 42, 6 will be referred for inpatient care while 94 will remain in outpatient care.

In all countries, R + ORS resulted in cost savings and a gain in quality of life. In Egypt, for R + ORS there was a cost savings of −236 EGP per gain of 0.0008 QALYs resulting in a dominant incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER) of −304,152 EGP/QALY gain versus ORS alone. In Morocco, for R + ORS there was a cost savings of −5 MAD per gain of 0.0008 QALYs resulting in a dominant ICER of −6,561 MAD/QALY gain versus ORS alone. In Philippines, for R + ORS there was a cost savings of −334 PHP per gain of 0.0008 QALYs resulting in a dominant ICER of −428,612 PHP/QALY gain versus ORS alone. In Vietnam, for R + ORS there was a cost savings of −88,595 VND per gain of 0.0008 QALYs resulting in a dominant ICER of −113,985,734 VND/QALY gain versus ORS alone. The results are presented in .

Table 2. Cost-effectiveness results in local country currency per country for Egypt, Morocco, Philippines and Vietnam.

All parameters are varied around 20%, or within plausible range (for example maximum utility is 1.00) for the purpose of univariate deterministic sensitivity analysis. Parameters that affect the results more than twenty percent are shown in . In general, the three most influential parameters across all country adaptations are the utility of children without diarrhea; the utility of inpatient children with diarrhea and the cost of one night of inpatient care. There is some variation due to inpatient referral at 48 hrs for ORS, diarrhoea resolution at 48 hrs for ORS, daily drug cost of R + ORS and outpatient consultation cost for Morocco and Philippines, but not for Egypt and Vietnam. On the other hand, the Egypt and Philippines versions show sensitivity to diarrhoea resolving at 48 hrs (R + ORS), but not the Egypt and Vietnam versions. All model adaptations show low (<20%) sensitivity to the parameter’s utility of outpatient children with diarrhoea, inpatient referral at 48 hrs (R + ORS), daily drug cost of ORS, the weighted average cost of adverse events, the proportion of children with adverse events (ORS and R + ORS) as shown in .

Table 3. Univariate sensitivity analysis, parameters influencing the results by more than twenty percent.

The reader is referred to a previous paper which details the exploration of the critical components of the model to demonstrate the robustness of the results, the principles hold true for the model adaptations because the underlying structure of the model has remained unchangedCitation43.

Discussion

The results show that according to the underlying evidence base and assumptions of the model adaptations, R + ORS is potentially cost-saving in Egypt, Morocco, Philippines, and Vietnam. There are strengths and limitations of the adaptations which should be considered.

One strength is that the adaptations comply with local country HTA guidelines, where available. For example, according to the Philippines guideline, cost-effectiveness is warranted in instances of superior efficacy, with cost utility being the preferred approachCitation23,Citation49. Expressing the outcome as preference-based QALY gain is acceptable, with the EQ-5D named as the preferred instrument for measuring health-related quality of lifeCitation17. As per the guideline, capital costs are not included and results are reported in Filipino pesos (PHP) Citation23. In keeping with the guideline, the model is based on the best available evidence and local clinical practice guideline inform clinical pathways and resource use, etc. The guideline advocates that the model mimics the patients’ pathway from current to final status, in this case: curedCitation23.

In Egypt, a preliminary set of recommendations is explored in a paper by Elsisi et al. in 2013 and a summary of recommendations is available via the International Society for Pharmacoeconomic Outcomes Research (ISPOR) websiteCitation24,Citation50. According to these recommendations, cost utility is accepted with measurement of utility with EQ5D preferred, deterministic analysis mandatory and probabilistic analysis optional.

In Vietnam, the Ministry of Health has assigned the Health Strategy and Policy Institute (HSPI) to oversee HTA activities in Vietnam to close the gap between HTA and policyCitation31,Citation32. According to Kieu’s commentary, HTA is in development due for completion in October 2017, however, no publicly available guideline is identifiedCitation31. To the best of our knowledge, no pharmacoeconomic HTA guidelines are available for Morocco and Vietnam. In the absence of national HTA guidelines for Morocco and Vietnam, it is worth noting that this research generally aligns with the international decision support initiative reference case which may be used to guide economic evaluation in LMICCitation34.

A further strength is that the model structure represents the clinical situation at the country level. In contrast to other medical conditions, there is almost universal agreement on clinical management and for the last three decades, international guidelines recommend ORS as the standard of careCitation12–14,Citation18. Once clinical features of dehydration are present, children are admitted to the hospital. This agreement in clinical scenarios across a wide range of high, upper-middle- and low-income countries means that the core model is highly amenable to adaptation to a wide range of countries because the inherent structure of the model is transferable to most clinical outpatient and inpatient settings. For example, in Egypt, a new consensus guideline for children with Acute Gastroenteritis recommends that primary care physicians evaluate the hydration status of children under five, and confirms that children with no dehydration can be managed at home and children at high risk of developing dehydration should be hospitalizedCitation15. Similarly in the Philippines, according to the Clinical Practice Guidelines of the Department of Health (2019), children with mild to moderate dehydration are treated with ORS, whereas, children with severe dehydration are given rapid intravenous rehydrationCitation18. The model aligns with both of these guidelines. In the Philippines, the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth) is the national single-payer for all hospital admissions and sets out acceptable interventions for inpatients and case ratesCitation16. Children admitted with diarrhea are reimbursed by PhilHealth with 6,000 PHP with a minimum length of stay of 3 daysCitation51. ORS and intravenous fluids are the standard treatment for dehydration caused by diarrhea and are administered based on the degree of dehydrationCitation16. The document states that the use of non-formulary "anti-diarrheal" drugs has no proven benefit and is not indicated for acute diarrheaCitation16. These include adsorbents such as kaolin, activated charcoal, cholestyramine, attapulgite and antimotility drugs including loperamide hydrochloride and diphenoxylate. Use of these non-formularies is penalized with non-payment of case ratesCitation16.

One of the limitations is that country-specific data is not available for all parameters in the model. There are two cost-driving components in the model: The first is the proportion of children in whom diarrhea does/does not resolve with ORS and R + ORS after 48 h after receiving ORS or R + ORS. In the country adaptations, this parameter is retained from the core model. Note that related publications show that this is a critical component of the modelCitation43. There is only one more recent study: a meta-analysis that confirms that R + ORS reduces time to cure from 4.4 days to 3.2 days and that the tolerability (described below) was comparable to placebo in both groupsCitation49. Unfortunately, the data cannot be used directly in the model because the outcomes do not align with the model structure (number of stools on the second day of treatment; time to cure, global efficacy categorized as markedly effective, effective or ineffective; global efficacy categorized as cured, improved or not-improved; % of patients cured after 72 h day of treatment) Citation49. However, it is worth noting that all outcomes favour racecadotrilCitation49. No other recent or country-specific data was available, so these parameters in the core model were retained.

The second cost driver is the proportion of children whose diarrhea does not resolve at the second visit who are referred for inpatient care. Implicit in this assumption is that they present with dehydration. To the best of our knowledge, no other studies reporting this endpoint have been published therefore this information was again retained in the core model.

Local country data is also not available for adverse events. More recently, Eberlin found that adverse event incidence was 10.4% for R + ORS versus 10.6% (comparator including placebo), respectively based on six blinded studies including 326 and 312 patients in their combined racecadotril and placebo armsCitation49. When this data is entered into the model the ICERs remain dominant and are −818,739 EGP/QALY gain for Egypt, −6,456 MAD/QALY gain for Morocco, −428,559 PHP/QALY gain for Philippines and −113,499,828 VND/QALY gain for Vietnam.

All country adaptations would benefit from local utility data for children under five who are well, children with diarrhea in an outpatient setting and children with diarrhea in an inpatient setting. However, no such data is currently available and is an area for future potential research. The utility used for outpatient and inpatient children with diarrhea comes from a study in the United Kingdom that measured the utility of children with rotavirus gastritis using EQ5DCitation47. Literature searching identified no studies measuring utility with EQ5D in children with diarrhea in any of the countries in question, or any comparable LMIC countries. Therefore, the results of the Martin study are retained in the adaptations such that utility of outpatient children with diarrhea (0.7345) and inpatient (0.6145) Citation35. The most closely comparable study measures utility in children with diarrhea in the upper-middle-income country Thailand, and reports the mean utility of hospitalised children with all-cause diarrhea as 0.604, lower than our base case inpatient valueCitation52. When this utility value is inputted in the adaptations, the ICER results remain dominant and are −296,256 EGP/QALY gain for Egypt, −6,391 MAD/QALY gain for Morocco, −417,485 PHP/QALY gain for Philippines and −111,026,561 VND/QALY gain for Vietnam.

The utility of a well-child (without diarrhea) is a proxy taken from a study measuring the utility of the general population in the United KingdomCitation37. No data for under-fives is available and there are challenges to measuring the utility of under-fivesCitation53,Citation54. Therefore, the mean value for under 25 s (0.94) is usedCitation48. The sensitivity analysis shows that all the model adaptations are most sensitive to this value. The highest variation occurs when the utility is increased above 0.94, which is unlikely to be the case in LMIC. It is more likely that the utility of a well-child would be lower due to living conditions, co-morbidities and socio-economic factors in LMIC. When the utility is lowered by 20% for sensitivity analysis the base case result varies far less (−17%) unanimously for all four adaptations. Therefore, we varied the utility to determine the lower threshold of cost-effectiveness. In all adaptations, R + ORS remained cost-effective versus ORS when the utility of well-child with diarrhea is greater than 0.65. A more recent study measures the utility in the general population in 20 countriesCitation55. The population norms across twenty countries for 18–24-year-old ranged from 0.869 to 0.990, the lower value is far greater than this threshold required for cost-effectivenessCitation55. Therefore, within the constraints of the adaptations, the cost utility of R + ORS versus ORS has been demonstrated.

Conclusions

In keeping with similar findings in upper-middle and high-income countries, the cost utility of R + ORS versus ORS is favourable in low-middle income countries for the treatment of children under five with acute watery diarrhoea.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This research was funded by Abbott Products Operations AG. The research team and authors had the final decision on the methods used to adapt the model, the parameters used and the content of the manuscript.

Declaration of financial/other interests

PK and NA have received honorarium from Abbott. KK and ARD are employed by Abbott. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

TR developed the original core model. AN performed the adaptation for Egypt, TR performed the other adaptations, TR drafted the manuscript, TR, MD, KT, AN, KK reviewed and provided substantial input into the manuscript.

Previous presentations

The core model (UK) and its adaptations to Malaysia and Thailand have been published. There are no publications or conference presentations relating to the Egypt, Morocco, Philippines and Vietnam adaptations described in this paper.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (207.9 KB)Acknowledgements

Thank you to Abbott country affiliates who provided the country data and the key opinion leaders Professors Ehab Khairy Elkhashab and Ahmed M Hamdy who provided cost estimates for Egypt.

References

- World Health Organisation. Report on the Second intercountry meeting on health technology assessment: guidelines on the establishment of programmes within national health system Washington (DC): WHO; [cited 2021 July 13]. Available from: https://applications.emro.who.int/docs/IC_Meet_Rep_2015_16354_en.pdf?ua=1.

- United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund. Levels & Trends in Child Mortality. UNICEF. 2020. [cited 14 July 2021]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/reports/levels-and-trends-child-mortality-report-2020.

- Levine MM, Nasrin D, Acácio S, et al. Diarrhoeal disease and subsequent risk of death in infants and children residing in low-income and middle-income countries: analysis of the GEMS case-control study and 12-month GEMS-1A follow-on study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(2):e204–e214.

- Global Burden of Disease Collaborators. Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of diarrhoea in 195 countries: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(11):1211–1228.

- Fischer TK, Duc Anh D, Antil L, et al. Health care costs of diarrheal disease and estimates of the cost-effectiveness of rotavirus vaccination in vietnam. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(10):1720–1726.

- Vu Nguyen T, Le Van P, Le Huy C, et al. Etiology and epidemiology of diarrhea in children in Hanoi, Vietnam. Int J Infect Dis. 2006;10(4):298–308.

- Abdel-Aziz1 SB, Mowafy MA, Galal YS. Assessing the impact of a community-based health and nutrition education on the management of diarrhea in an urban district, cairo, Egypt. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;8(2):46–55.

- The World Bank. Diarrhea Treatment Percentage of Children Under 5 Who Received Oral Rehydration Solution Packet. Country Indicators [cited 2022. January 19]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.ORTH.

- Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS), Egypt. Population Demographics. [cited 2020. July 19]. Available from http://www.capmas.gov.eg/.

- Haut Commissariat au Plan (HPC) Morocco. Population Demographics. [cited 2020. July 16]. Available from: www.hcp.ma.

- Philippine Statistics Authority. [cited 2020. July 13]. Available from: https://psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/attachment/hsd/pressrelease/Table4_9.pdf.

- Armon K, Lakhanpaul M, Stephenson T. An evidence and consensus based guideline for acute diarrhoea management. Arch Dis Child. 2002;86(2):138.

- World Health Organization (WHO). The treatment of diarrhoea – a manual for physicians and other senior health workers. 2005. [cited 14 July 2021]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43209.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Diarrhoea and vomiting caused by gastroenteritis – diagnosis, assessment and management in children younger than 5 years. 2009. [cited 14 July 2021]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK63844/.

- El-Khayat H, El-Hodhod M, Gad S, et al. Management of acute gastroenteritis in children below five years by general practitioners: an egyptian consensus. J Gastrointest Dig Syst. 2021;11(5):2–8.

- PhilHealth Website. PhilHealth Circular No 2016-001. Policy statement on the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Gastroenteritis as reference by the Corporation in ensuring quality of care. 2016. [cited 14 July 2021]. Available from: https://www.philhealth.gov.ph/circulars/2016/circ2016-001.pdf.

- Philippines Department of Health. Philippine National Formulary Manual for Primary Healthcare 8th Edition. Manila: Philippines, 2014. [cited 14 July 2021]. Available from: https://caro.doh.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/PNF-Manual-for-Primary-Healthcare.pdf.

- Philippines Department of Health. Adoption of the National Food and Waterborne Disease Prevention and Control Program Clinical Practice Guideline on Acute Infectious Diarrhea Reference Manual Department Circular 2019-0233. 2019. [cited 14 July 2021]. Available from: https://doh.gov.ph/sites/default/files/publications/FWBD%20MOP%202019.pdf.

- Sultana R, Luby S, Gurley ES, et al. Cost of illness for severe and non-severe diarrhea borne by households in a low-income urban community of Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(6):e0009439.

- At Thobari J, Sutarman Mulyadi AWE, et al. Direct and indirect costs of acute diarrhea in children under five years of age in Indonesia: health facilities and community survey. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2022;19:100333.

- Barakat A, Halawa EF. Household costs of seeking outpatient care in Egyptian children with diarrhea: a cross-sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;14:42.

- Hasan MZ, Mehdi GG, De Broucker G, et al. The economic burden of diarrhea in children under 5 years in Bangladesh. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;107:37–46.

- Health Technology Assessment Unit, Department of Health Philippines. Philippine Health Technology Assessment Methods Guide. Methodological standards in evaluation of health technologies in the Philippines. First Edition. 2020. [cited 14 July 2021]. Available from: https://doh.gov.ph/sites/default/files/health_advisory/HTA%20Methods%20Guide_Public%20Consultation%2003.2020_1.pdf.

- Elsisi GH, Kalo Z, Eldessouki R, et al. Recommendations for reporting pharmacoeconomic evaluations in Egypt. Value Health Reg Issues. 2013;2(2):319–327.

- Farid S, Elmahdawy M, Baines D. A systematic review on the extent and quality of pharmacoeconomic publications in Egypt. Clin Drug Investig. 2019;39(2):157–168.

- Tran BX, Nong VM, Maher RM, et al. A systematic review of scope and quality of health economic evaluation studies in vietnam. PLOS One. 2014;9(8):e103825.

- Alefan Q, Rascati K. Pharmacoeconomic studies in world health organisation Eastern Mediterranean countries: reporting completeness. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2017;33(2):215–221.

- Khoudri I, Belayachi J, Dendane T, et al. Measuring quality of life after intensive care using the arabic version for Morocco of the EuroQol 5 dimensions. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5(1):56.

- Griffin AE, Ragab G, Ziada S, et al. Setting recommendations for good practice of health technology assessment in the Egyptian ministry of health. Value in Health. 2016;19(7):A497.

- Griffiths UK, Legood R, Pitt C. Comparison of economic evaluation methods across low-income, middle-income and high-income countries: What are the differences and why? Health Econ. 2016;25(Suppl 1):29–41.

- Researchgate. 2017. News Across Asia. Health Technology Assessment and Its Application in Vietnam. [cited July 13 2021]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Tuan-Kieu/publication/318351014_Health_Technology_Assessment_and_Its_Application_in_Vietnam/links/59e045890f7e9bc512589519/Health-Technology-Assessment-and-Its-Application-in-Vietnam.pdf.

- Vo TQ. Health technology assessment in developing countries: a brief introduction for vietnamese health-care policymakers. Asian J Pharm. 2018;12(1). DOI:10.22377/ajp.v12i01.2340

- Sharma M, Teerawattananon Y, Dabak SV, et al. A landscape analysis of health technology assessment capacity in the association of South-East Asian Nations Region. Health Res Policy Syst. 2021;19(1):19.

- Wilkinson T, Sculpher M, Claxton K, et al. The international decision support initiative reference case for economic evaluation: an aid to thought. Value Health. 2016;19(8):921–928.

- World Health Organisation. WHO. 2015 Global Survey on Health Technology Assessment by National Authorities. Geneva Switzerland. 2015. [cited 13 July 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-technology-assessment/MD_HTA_oct2015_final_web2.pdf.

- Manca A, Willan AR. 'Lost in translation': accounting for between-country differences in the analysis of multinational cost-effectiveness data. Pharmacoeconomics. 2006;24(11):1101–1119.

- Mullins DC, Onwudiwe NC, de Aruajo GTB, et al. Guidance document: global pharmacoeconomic model adaption strategies. Value Health Reg Issues. 2014;5:7–13.

- Drummond M, Barbieri M, Cook J, et al. Transferability of economic evaluations across jurisdictions: ISPOR good research practices task force report. Value Health. 2009;12(4):409–418.

- Matheson AJ, Noble S. Racecadotril. Drugs. 2000;59(4) :829–35. discussion 836:–7.

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). List of Nationally Authorised Medicinal Products. [cited 2022. January 20]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/psusa/racecadotril-list-nationally-authorised-medicinal-products-psusa/00002602/202003_en.pdf.

- Rautenberg TA, Zerwes U, Foerster D, et al. Evaluating the cost utility of racecadotril for the treatment of acute watery diarrhea in children: the RAWD model. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2012;4:109–116.

- Rautenberg TA, Zerwes U. The cost utility and budget impact of adjuvant racecadotril for acute diarrhea in children in Thailand. CEOR. 2017;9:411–422.

- Rautenberg TA, Zerwes U, Lee WS. Cost utility, budget impact, and scenario analysis of racecadotril in addition to oral rehydration for acute diarrhea in children in Malaysia. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;10:169–178.

- Lehert P, Cheron G, Alvarez Calatayud G, et al. Racecadotril for childhood gastroenteritis: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43(9):707–713.

- Alvarez Calatayud E, Pinei Simon G, Taboada Castro L, et al. Efectividad de racecadotrilo en el tratamiento de la gastroenteritis aguda [the effectiveness of racecadotril in the treatment of acute gastroenteritis]. Acta Pediatr.Esp. 2009;67(3):117–122.

- Baumer P, Joulin Y. Pre- and postmarketing safety profiles of racecadotril sachets, a “new” antidiarrhoeal drug. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48(Suppl 3):E99.

- Martin A, Cottrell S, Standaert B. Estimating utility scores in young children with acute rotavirus gastroenteritis in the UK. J. Med Econ. 2008;11(3):471–484.

- Kind P, Hardman G, Macran S. UK population norms for EQ-5D, discussion paper 172. Centre for Health Economics York University; 1999. Available from: https://www.york.ac.uk/che/pdf/DP172.pdf

- Eberlin M, Chen M, Mueck T, et al. Racecadotril in the treatment of acute diarrhea in children: a systematic, comprehensive review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18(1):124.

- International Society for Pharmacoeconomic Outcomes Research ISPOR. Pharmaceconomic Guidelines Around the World, Egypt. 2021. [cired 14 July 2021]. Available from: https://tools.ispor.org/PEguidelines/countrydet.asp?c=39&t=1.

- PhilHealth Website. Annex A. List of Medical Case Rates. 2017. [cited 14 July 2021]. Available from: https://www.philhealth.gov.ph/circulars/2017/annexes/0019/AnnexA-MedicalCaseRates.pdf.

- Rochanathimoke O, Riewpaiboon A, Postma MJ, et al. Health related quality of life impact from rotavirus diarrhea on children and their family caregivers in Thailand. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;18(2):215–222.

- Thorrington D, Eames K. Measuring health utilities in children and adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. PLOS One. 2015;10(8):e0135672.

- Ungar WJ. Challenges in health state valuation in paediatric economic evaluation: are QALYs contraindicated? Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29(8):641–652.

- Janssen MF, Szende A, Cabases J, et al. Population norms for the EQ-5D-3L: a cross-country analysis of population surveys for 20 countries. Eur J Health Econ. 2019;20(2):205–216.