Abstract

Background

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a lifelong burdensome disorder of heterogenic expression. This study investigated the longer-term economic burden of severe presentation of SCD. As SCD treatment landscapes evolve toward curative intent gene therapies, understanding how SCD-associated costs may change over the patient lifetime will be important for medical decision-making.

Methods

Patients with severe presentation of SCD (presence of acute vaso-occlusive events [VOEs] or history of stroke and/or other disease-related sequelae), were identified within the MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental and Multi-state Medicaid Databases from 1/1/2010 to 12/31/2018. The first SCD claim served as the index date and patients were followed over a 5-year post-period. Clinical characteristics and healthcare resource utilization and costs were assessed over follow-up for eligible cohorts of commercial and Medicaid patients with severe SCD presentation and age-based subgroups (<18, 18–30, and ≥31).

Results

A total of 4,487 patients, primarily insured via Medicaid (79.2%), qualified for the analysis. Patients evidenced persistent VOEs over follow-up; prevalence of most comorbidities increased with age. Mean total healthcare costs over the 5-year follow-up were $275,143 (SD± $406,770) and $362,728 (SD± $620,189) in the commercial and Medicaid samples, respectively. Disease severity, assessed by the number of VOEs and utilization of inpatient and emergency services, peaked in the 18–30 year group in both samples. These groups also evidenced the highest mean healthcare costs over the 5-year follow-up at $344,776 (SD± $434,521) and $671,321 (SD± $938,764) in the commercial and Medicaid samples respectively.

Conclusion

Results indicate high clinical need and economic burden among patients with severe presentation of SCD. These findings not only highlight the need for improved therapeutic options to limit or prevent disease progression, but also start to provide insight on lifetime costs of SCD that will be needed in the evaluation of emerging curative intent therapies.

Introduction

As sickle cell disease (SCD) is a lifelong, monogenic disorder of a chronic, progressive nature, studying disease trajectory across the full lifespan is critically important to understanding the complete burden of SCD.Citation1–3 The condition is associated with reduced quality of life (QoL) and high rates of morbidity and mortality.Citation4–6 Studies to date have demonstrated a notable economic burden of SCD due to costs of day-to-day disease management, the development of comorbidities and disease-related complications overtime, and lost productivity.Citation4,Citation7–11 Healthcare costs are largely driven by high utilization of emergency and inpatient services to manage vaso-occlusive events (VOEs), comorbidities, and other disease-related complications, and can be extremely variable depending on disease progression, presence of complications, number of VOEs, and other patient factors.Citation6–10,Citation12–14

Currently available disease-modifying therapies, including medications and red blood cell transfusions, play a role in pain management and may reduce the frequency and severity of acute events.Citation15,Citation16 However, these therapies are not able to fully eliminate VOEs or stop long-term disease progression; thus, they can only offer limited QoL improvement and are unlikely to support a meaningful reduction in disease-driven societal or economic burden. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (alloHSCT) is a curative intent therapy that should halt progression of SCD, and it has been associated with a remarkable improvement in patients’ health-related QoL across different domains.Citation17 However, application of the procedure requires availability of a matched and willing donor and carries risks of toxicity from conditioning regimens, graft versus host disease, infertility, and graft failure, all of which limit the proportion of the SCD population eligible for the procedure. Different modifications of the allogenic transplant process, including using alternative donor and conditioning regimens, are being studied to improve availability of this technique. Outcomes are improving, but to date remain suboptimal compared to a matched related donor in the pediatric population with myeloablative conditioning. Promising innovations in gene therapy are also on the horizon; these one-time interventions seek to correct the underlying biological cause of SCD and thus have the potential to fundamentally change the trajectory of disease, providing life-changing benefits to patients, healthcare systems, and society at large. Overall, it is an exciting and momentous period in the treatment development landscape for individuals with SCD who’s healthcare needs have been ignored, misunderstood, and under supported for far too long.

Although multiple costing studies on SCD are available, few provide current, longitudinal assessment of patients with a more severe presentation of disease, whom are the focus of curative intent therapy and ongoing gene therapy clinical trials. This study examined patient characteristics and the economic burden of disease over a 5-year period in a population of patients with severe presentation of SCD, defined as evidence of either persistent acute VOEs or history of stroke and/or other disease-related sequelae. The prolonged, 5-year duration of follow-up as well as inclusion of both commercially and publicly insured individuals and patients of all ages provides a comprehensive, longitudinal assessment of severe presentation of SCD in the United States. Further, investigation of the clinical and economic burden of disease across various age groups helps to provide additional insight into the trajectory of disease over the lifespan of disease. Understanding of longer-term patient costs is expected to be of particular importance in understanding the potential value of anticipated one-time gene therapies.

Methods

Data source

This study utilized the MarketScan Commercial, Medicare Supplemental, and Multi-state Medicaid Databases, composed of de-identified administrative claims data, from 1/1/2010 through 12/31/2018. The three databases contain all healthcare claims (inpatient, outpatient, and outpatient pharmacy) for patients covered via private or public insurance plans. The commercial database is derived from employer-sponsored health plans and contains data from employees and their dependents. The Medicare supplemental database includes individuals with a Medicare supplemental insurance policy provided by a current or former employer; both supplemental insurance and Medicare-paid portions of claims are represented. The Medicaid database collects enrollee data from multiple states. All study data were obtained using International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM) codes, Current Procedural Terminology 4th edition codes, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes, and National Drug Codes. Because this study used only de-identified patient records and did not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, this study was exempted from Institutional Review Board approval.

Patient selection

The sample included individuals with severe presentation of SCD, defined as evidence of acute VOE or history of stroke and/or other disease-related sequelae. Eligible patients had ≥2 claims with a diagnosis of SCD in a 12-month period; the first SCD claim served as the index date. Patients were also required to be continuously enrolled with medical and pharmacy benefits for 60-month post-index and not have a bone marrow or stem cell transplant during follow-up for any reason; Medicaid patients who were dual eligible for Medicare were excluded from the study sample. The prolonged duration of follow up (5 years) was imposed to offer more longitudinal insight into disease progression and associated costs; this was determined to be of particular importance in assessing patients with chronic disease-related sequelae for whom progression of morbidity-associated cost is less well characterized. Although the requirement for 60 months of post-index continuous eligibility could impose selection bias, the authors felt this tradeoff (vs. a shorter duration of observation) was justified in order to support research where gaps persist.

Patients were also required to have evidence of either acute VOEs or history of stroke and/or other disease-related sequelae in the 24-months following index. This requirement was imposed to classify patients as having severe presentation of disease for whom, again, are more likely to be earlier candidates for gene therapy. Patients were permitted to evidence both acute VOEs or history of stroke and other disease-related sequelae. No distinctions, other than reporting the proportions qualifying for each category, were made between patients who qualified for the acute VOE or history of stroke versus the other disease-related sequelae criteria in the remainder of the analysis. Acute VOEs or history of stroke was defined as ≥1 of: ≥4 inpatient admissions or emergency visits carrying a VOE diagnosis (SCD crisis, splenic sequestration, hepatic sequestration/infarction, or priapism); a diagnosis of acute chest syndrome; a diagnosis of stroke. Other disease-related sequelae were defined as ≥1 claim for any of the following: osteomyelitis, sepsis, splenic infarction, acute kidney injury or chronic kidney disease, acute renal failure, embolism (venous thromboembolism, deep vein thrombosis, or pulmonary embolism), osteonecrosis, pulmonary hypertension, pre-eclampsia/eclampsia, hepatic sequestration/infarction, stroke, or non-pressure ulcers.

Outcomes and descriptive analyses

Eligible patients were followed over a 5-year post-index period; analyses were conducted separately in the MarketScan Commercial/Medicare Supplemental and Medicaid databases. Outcomes were assessed for the full eligible samples of commercial/Medicare supplemental (hereafter referred to as commercial) or Medicaid patients with SCD and age-based subsets within each (<18, 18–30, and ≥31). Demographics were assessed on the index date. Post-period outcomes included clinical and treatment characteristics as well as healthcare resource utilization and costs all of which were assessed over the full 5-year post-index period and on an annual basis (e.g. year 1, year 2, etc.). All-cause healthcare resource utilization included inpatient admissions, outpatient (emergency room [ER] visits, office visits, and other services) encounters, and outpatient pharmacy fills. Costs were calculated based on paid amounts on adjudicated claims including both insurer and patient payment and inflated to 2018 US medical prices using the medical component of the consumer price index; costs for capitated plans were estimated via payment proxy. Categorical variables are reported as frequency and percent; continuous variables are reported as mean with standard deviations (±SD); see Supplemental materials for median reporting. All analyses were conducted using WPS version 4.1 (World Programming, UK).

Data sharing

The data that were used for this study are available from Merative. Restrictions apply to the availably of this data, which were used under license for this study.

Results

Study population

A total of 4,487 patients qualified for the analysis; 79.2% of patients were covered by a Medicaid plan (). The majority of both the commercial (76.7%) and the Medicaid samples (91.4%) had evidence of acute VOEs or history of stroke in the first 24 months, while 58.0% of commercial patients and 45.8% of Medicaid patients exhibited ≥1 other disease-related sequelae over the same period. The Medicaid sample was younger than the commercial sample with a mean age of 15.2 (SD± 14.3) vs. 28.3 (SD± 19.2); age distributions within Medicaid and commercial samples were 63.6% vs. 37.4% <18 years old, 21.5% vs. 17.9% 18–30 years old, and 14.9% vs. 44.8% ≥31 years old, respectively (). There were slightly more females (59.4%) in the commercial sample. Race information was only available within the Medicaid sample; consistent with disease epidemiology in the United States, approximately 75% of the sample was black with another 24% classified as other/unknown race ().

Table 1. Sample attrition.

Table 2. Demographic, clinical, and treatment characteristics.

Clinical characteristics

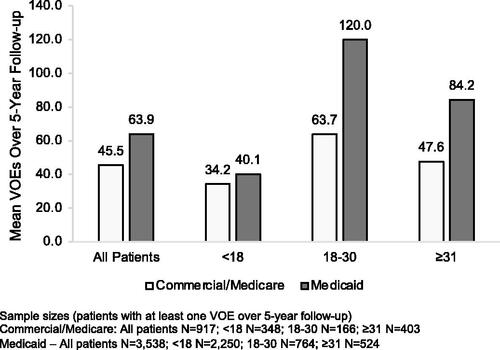

The vast majority of patients in both the commercial (98.2%) and Medicaid (99.6%) cohorts had ≥1 VOE over the 5-year follow-up; mean number of VOEs per patient over the full follow-up was 45.5 (SD± 64.8) in the commercial cohort and 63.9 (SD± 95.9) in the Medicaid cohort (). On a year-over-year basis the proportion of patients with ≥1 VOE in a 1-year period ranged from 75.6%-97.3% in commercial and 83.0–98.6% in Medicaid patients. The commercial sample had an average of 10.2 (SD± 12.8) to 10.9 (SD± 19.0) VOEs on an annual basis; mean number of annual VOEs in the Medicaid sample ranged from 13.2 (SD± 19.5) to 14.5 (SD± 24.6). The mean number of VOEs over the 5-year follow-up peaked in the 18–30 year group in both samples. In the commercial sample the number of VOEs increased from 34.2 (SD± 33.1) in the <18 year group to 63.7 (SD± 79.6) in the 18–30 year group before declining to 47.6 (SD± 75.9) in the ≥31 year group; in the Medicaid sample the number of VOEs in the <18, 18–30, and ≥31 year groups was 40.1 (SD± 51.4), 120.0 (SD± 134.2), and 84.2 (SD± 130.6), respectively ().

While the commercial and Medicaid samples had similar proportions of patients with comorbidities over the 5-year follow-up (), the percentage of patients with comorbidities varied across the three age groups (). There was a general trend of increasing comorbidity with older age, which is consistent with the chronic progressive nature of the disease. Compared to the <18 year group, patients in the 18–30 and ≥31 groups for both the Commercial and Medicaid samples reported at least a 50% age-associated increase in the proportion of affected patients for at least 14 of 31 (45.2%) of the comorbidities studied.

Table 3. Comorbidities and disease-related complications over the 5-year follow-up by age groups.

From a treatment perspective, utilization of antibiotics and pain medications was extremely common over the 5-year follow-up; conversely, the percentage of patients using SCD disease modifying therapies over the 5-year follow-up was generally lower (). SCD therapy utilization trends were relatively static year-over-year with the exception of hydroxyurea use which increased from 29.0% to 41.8% in the Medicaid cohort and 25.1–34.0% in the commercial cohort over the 5-year study period. The greatest utilization of SCD therapies was observed in the 18–30 year group who also had the highest disease severity as measured by VOE frequency ().

Table 4. Treatment utilization over the 5-year follow-up by age group.

Healthcare resource utilization and costs

There was high healthcare resource utilization over the follow-up period in both samples with almost universal use of outpatient visits, other outpatient services, and outpatient pharmacy. There was also high utilization of inpatient and ER services. Over the 5-year follow-up, 90.3% of commercial and 93.8% of Medicaid patients had ≥1 inpatient admission with an average of 7.0 (SD± 9.7) and 11.0 (SD± 15.0) admissions, respectively. Average length of stay per admission was 4.1 (SD± 3.7) in the commercial sample and 3.7 (SD± 2.7) for Medicaid patients. The majority of both commercial (94.2%) and Medicaid (97.9%) patients also had ≥1 ER visit, with an average of 11.5 (SD± 22.6) and 23.2 (SD± 46.2) visits over the 5-year follow-up respectively. Annually, the percentage of patients with ≥1 hospitalization ranged from 48.4% to 68.2% in the commercial sample with the average number of hospitalizations ranging from 1.2 (SD± 2.2) to 1.7 (SD± 2.3). In the Medicaid sample, between 57.1% and 73.0% of patients had ≥1 hospitalization on an annual basis with the mean number of annual hospitalizations ranging from 2.1 (SD± 3.5) to 2.4 (SD± 3.4). Annual percentages of patients with ≥1 ER visit ranged from 57.6% to 73.4% in the commercial/Medicare sample and 74.0–82.6% in the Medicaid sample. The average number of annual ER visits ranged from 2.1 (SD± 5.3) to 2.6 (SD± 4.4) in the commercial and 4.4 (SD± 9.0) to 4.8 (SD± 11.9) Medicaid samples. The 18–30 year group evidenced increased numbers of inpatient admissions and ER visits compared to both the <18 and ≥31 year groups in both samples. There were slight increases in the per-admission length of stay in the 18–30 and ≥31 year groups compared to the <18 groups in both the commercial and Medicaid samples. Numbers of office visits, other outpatient services, and outpatient pharmacy fills tended to increase across the three age groups in both the commercial and Medicaid populations.

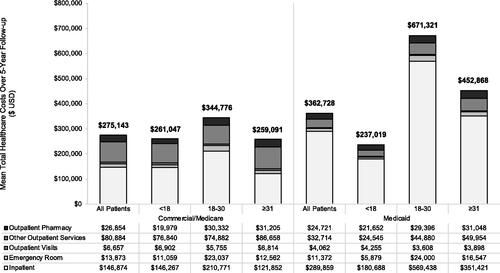

Consistent with high utilization of healthcare services, healthcare costs were substantial over the follow-up period (). The commercial cohort incurred mean total all-cause healthcare costs of $275,143 (SD± $406,770) over the 5-year follow-up, while mean total all-cause healthcare costs for the Medicaid sample over the same period were $362,728 (SD± $620,189). Annual mean costs ranged from $51,598 (SD±$89,814) to $60,058 (SD± $99,156) in the commercial sample and $67,482 (SD± $164,011) to $77,321 (SD± $179,278) for Medicaid patients. Inpatient costs were the primary driver of total healthcare costs in both the commercial and Medicaid samples (). The highest total 5-year healthcare costs were observed in the 18 to 30 year group in both the commercial ($344,776 [SD± $434,521]) and Medicaid ($671,321 [SD± $938,764]) samples, consistent with the observed increases in service utilization, number of VOEs, and prevalence of comorbidities in this group (). Average annual costs of care for the 18 to 30 year groups ranged from $59,284 (SD± 93,396) to $81,455 (SD± $140,449) for commercial patients and $127,827 (SD± $181,734) to $149,154 (SD± 288,521) for Medicaid patients. In the commercial sample, costs in the 18–30 year group were 1.3-fold higher than those in the <18 year group; differences between age groups were even more notable in the Medicaid sample where the 18–30 year group evidenced total mean healthcare costs 2.8-fold higher than the <18 year group.

Discussion

With improved newborn screening and disease management options over 95% of children in the United States with SCD now survive to adulthood.Citation3,Citation4,Citation8,Citation18 Despite this, life expectancy remains 20–30 years lower as compared to individuals without SCD.Citation19,Citation20 Living with SCD requires management of a multitude of comorbidities and disease-related complications that are by no means trivial, making it more important than ever to understand the long-term burden of this progressive disease. This retrospective, longitudinal analysis utilized the MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental and Multi-state Medicaid Databases to explore clinical and economic burden of SCD over a 5-year period; further, investigation of three distinct age-based subgroups provided insight into alterations in disease presentation and burden over the full lifespan of disease. The results from this analysis provide an updated real-world, longitudinal assessment of the burden of severe presentation of SCD in the United States.

Overall, the majority of SCD patients (79.2%) were found in the Medicaid Database, partially due to a greater proportion of the potential Medicaid sample exhibiting severe presentation of disease (58.2% in Medicaid vs. 41.4% in commercial). Clinically, SCD in both databases was characterized by persistent VOEs over the 5-year follow-up and the progressive accumulation of comorbidities and disease-related complications with increasing age. Regardless of insurance type, patients with SCD exhibited high utilization of both inpatient and emergency services in addition to regular use of outpatient services. Frequent need of healthcare services, and most notably inpatient services, translated to high healthcare costs in this population. Examination of the three age-based subgroups also provided insight into the progression of SCD presentation over the lifespan. Specifically, we observed indicators of increased disease severity in late adolescence to young adulthood (18–30 year group) compared to other age groups, including high numbers of VOEs, a spike in comorbidity burden, high utilization of inpatient and emergency services, and high costs of care.

The trend for increased disease severity in late adolescence to young adulthood observed here likely derives from both clinical and institutional components.Citation6,Citation8,Citation21 This period marks a particularly vulnerable time in SCD as the transition from pediatric to adult care coincides with the emergence of end organ damage, resulting from years of SCD-related tissue damage, and increased prevalence of chronic pain crises.Citation18,Citation21,Citation22 Although we did not expressly examine this interaction between disease severity and pediatric-to-adult care transitions, we are seeing trends reported elsewhere.Citation18,Citation21 In our analysis, the 18–30 year subgroups only accounts for approximately 20% of patients in both the commercial and Medicaid samples. The sharp decline in sample size in both the commercial and Medicaid samples from the <18 year group to the 18–30 year group is likely associated with shifting insurance eligibility and access to care once minors become adults. Clinically, we also observe a shift toward increased reliance on inpatient/emergency care settings in the 18–30 year group in both the Medicaid and commercial samples as evidenced by lower ratios of outpatient:inpatient or outpatient: ER visits in the 18–30 year group compared to either the <18 or ≥31 year groups. For example, in the Medicaid sample, the 18–30 year group had 2.9 outpatient visits/inpatient visit and 1.2 outpatient visits/emergency visit over follow-up while the <18 year group had 7.4 outpatient visits/inpatient admission and 4.4 outpatient visits/ ER visit. These apparent shifts to a greater reliance on inpatient and emergency services for care within the 18–30 year group could be indicative of limited use of regular preventative care services whether derived from healthcare access, poor transition from pediatric to adult healthcare providers, or other circumstances.Citation18,Citation21–24 While today’s treatment options remain inadequate for many patients, suboptimal utilization of these therapies only amplifies issues with management of disease, resulting in higher rates of disease-related morbidity, poorer patient QoL, earlier mortality, and higher healthcare costs and patient productivity loss.

The costs associated with severe presentation of SCD identified within this analysis indicates a notable economic burden of disease, with estimated 5-year total healthcare costs of $275,143 in the commercial sample and $362,728 in the Medicaid sample. Healthcare costs peaked between 18 and 30 years of age with mean total 5-year costs of $344,776 and $671,321 in the commercial and Medicaid samples, respectively. Although annual cost estimates for SCD populations vary in the literature, most likely due to underlying differences in populations studied or research methods employed, other recent estimates place costs from approximately $17,000 to $83,000 annually.Citation8–10,Citation13,Citation14,Citation25 Annual costs in our study are at the higher end of this range at $55,000 and $73,000 in our commercial and Medicaid samples, respectively, consistent with our focus on patients with more severe disease. One of the more recent analyses by Shah et al. identified annual mean costs for patients with SCD based on the number of VOEs experienced. Their cohort of patients with ≥2 VOEs in 12-months closely aligns with one of our acute VOEs or history of stroke criteria, and their cost estimates of $64,555, $64,566, and $58,308 in commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid populations, respectively, are also aligned with our findings.Citation10 Further, the stratifications of healthcare costs based on the number of VOEs provided by both Shah et al. and Johnson et al. reveal that costs for patients with ≥2 VOEs are approximately 3–4-fold higher than costs for patients with 0 VOEs providing additional context for the impact of disease severity when estimating the burden of SCD.Citation10,Citation14 Other studies have also found notable elevations (e.g. approximately 4-fold increases) in costs among SCD patients who were high utilizers of inpatient services or patients with end organ damage compared to patients with lower resource utilization or less advanced disease.Citation7,Citation13 Although our analysis did not expressly look at costs stratified by disease severity, our finding of both increased disease severity and higher total healthcare costs in the 18–30 year group is consistent with the correlation between disease severity and costs in these previously published works. The differences in cost trends between our commercial and Medicaid samples may also speak to the relationship between severity and cost as we observe both increased healthcare costs and disease severity in the Medicaid versus commercial adult cohorts.

Limitations of this analysis include those associated with the use of administrative claims data for assessment of health outcomes. Administrative claims data are collected for billing and not research purposes; although these data are particularly well suited to assessments of healthcare costs, they can lack clinical detail that may be available as part of regular clinical assessment. Therefore, estimation of clinical characteristics within claims databases are restricted to coding and reporting limitations in the data and may further be subject to miscoding or coding errors. Toward this point, the number of VOEs assessed in this study was based on the number of inpatient admissions or ER visits during follow-up period with one of the defined VOE diagnosis used in the analysis. Therefore, the number of VOEs reported represents an estimate of the total number of VOE episodes. Actual numbers of VOEs may be higher if alternative diagnoses not assessed here were assigned to the VOE or lower in the case of VOE episodes that required multiple healthcare encounters to resolve. Additionally, healthcare resource utilizations presented here were calculated based on all-cause service utilization. Previous studies have reported that SCD-related resource use comprises the majority of all-cause resource use for SCD patients; however, it is possible that non-SCD related resource use is responsible for some of the trends observed here.Citation9 It is also worth noting that as with most administrative claims analyses healthcare cost data within this population is skewed. Further, although the sample for this study was sourced from both commercial and public insurance claims database, results may not generalize to specific subsets of insured patients or the un/underinsured. As noted previously, only patients with 5-years of follow-up were retained in the study sample. The goal of imposing a long period of continuous eligibility was to understand long-term costs and progression of SCD over the lifespan of disease. However, this methodology also results in the exclusion of patients who dis-enroll from insurance or die within 5-years; therefore, the findings of this study are specific to patients with at least 5 years of enrollment. From a medication perspective, utilization was examined at a high level by reporting the number and percentage of patients with evidence of at least one medication fill/administration; no information on duration of use or medication adherence was examined. Therefore, the impact of medication adherence on healthcare resource utilization and costs was not investigated.Citation25 It should also be noted that utilization of newer SCD therapies such as voxelotor and crizanlizumab are not reflected in these analyses due to period of data used; it would be expected that continued treatment with these medications would lead to escalated healthcare costs for users.

Our findings indicate that severe presentation of SCD is associated with a high burden of disease, both from clinical and economic perspectives, that progresses over the lifespan. Patients with severe presentation of SCD face lifelong, progressive complications that require intensive disease management translating to extremely high utilization of healthcare services. With clinical research advancing the possibility of one-time curative intent therapies, an understanding of the anticipated lifetime disease morbidity and cost is essential to supporting medical care decision-making, as the potential value for these new therapies will need to be considered from a lifetime perspective.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This analysis was funded by bluebird bio.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

MG and AC are employees of bluebird bio and Company shareholders. BLB is an employee of Merative who was funded by bluebird bio to conduct this analysis. SMB has received consultancy fees from bluebird bio, and Sanofi Genzyme; advisory board fees from Chiesi, Global Blood Therapeutics, Inc. (GBT), and Forma Therapeutics; and research funding from Pfizer.

Author contributions

MG, AC, and SMB designed the research study, BLB analyzed the data, MG, AC, SMB, and BLB interpreted the data, BLB drafted the article, MG, AC, and SMB critically revised the article, and all authors approved the submitted final version of the article.

Acknowledgement

None

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (64.4 KB)References

- Telen MJ, Malik P, Vercellotti GM. Therapeutic strategies for sickle cell disease: towards a multi-agent approach. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18(2):139–158.

- Sundd P, Gladwin MT, Novelli EM. Pathophysiology of sickle cell disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2019;14:263–292.

- Kato GJ, Piel FB, Reid CD, et al. Sickle cell disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):10810.

- Lubeck D, Agodoa I, Bhakta N, et al. Estimated life expectancy and income of patients with sickle cell disease compared with those without sickle cell disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1915374.

- DeBaun MR, Ghafuri DL, Rodeghier M, et al. Decreased medial survival of adults with sickle cell disease after adjusting for left truncation bias: a pooled analysis. Blood. 2019;133(6):615–617.

- Lee S, Vania DK, Bhor M, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and economic burden of adults with sickle cell disease in the United States: a systematic review. Int J Gen Med. 2020;13:361–377.

- Campbell A, Cong Z, Agodoa I, et al. The economic burden of end-organ damage among medicaid patients with sickle cell disease in the United States: a population based longitudinal claims study. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26(9):1121–1129.

- Kauf TL, Coates TD, Huazhi L, et al. The cost of health care for children and adults with sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol. 2009;84(6):323–327.

- Shah N, Bhor M, Xie L, et al. Treatment patterns and economic burden of sickle-cell disease patients prescribed hydroxyurea: a retrospective claims-based study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17(1):155.

- Shah NR, Bhor M, Latremouille-Viau D, et al. Vaso-occlusive crises and costs of sickle cell disease in patients with commercial, medicaid, and medicare insurance – the perspective of private and public payers. J Med Econ. 2020;23(11):1345–1355.

- Holdford D, Vendetti N, Sop DM, et al. Indirect economic burden of sickle cell disease. Value Health. 2021;24(8):1095–1101.

- Ballas SK. The cost of health care for patients with sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol. 2009;84(6):320–322.

- Carroll CP, Haywood C, Fagan P, et al. The course and correlates of high hospital utilization in sickle cell disease: evidence from a large urban medicaid managed care organization. Am J Hematol. 2009;84(10):666–670.

- Johnson KM, Jiao B, Ramsey SD, et al. Lifetime medical costs attributable to sickle cell disease among nonelderly individuals with commercial insurance. Blood Adv. 2022. DOI:10.1182/bloodadvances.2021006281

- Bakanay SM, Dainer E, Clair B, et al. Mortality in sickle cell patients on hydroxyurea therapy. Blood. 2005;105(2):545–547.

- Hankins J, Jeng M, Harris S, et al. Chronic transfusion therapy for children with sickle cell disease and recurrent acute chest syndrome. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;27(3):158–161.

- Badawy SM, Beg U, Liem RI, et al. A systematic review of quality of life in sickle cell disease and thalassemia after stem cell transplant or gene therapy. Blood Adv. 2021;5(2):570–583.

- Inusa BPD, Stewart CE, Mathurin-Charles S, et al. Paediatric to adult transition care for patients with sickle cell disease: a global perspective. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(4):e329–e341.

- Quinn CT, Rogers ZR, McCavit TL, et al. Improved survival of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2010;115(17):3447–3452.

- Colombatti R, Sainati L, Trevisanuto D. Anemia and transfusion in the neonate. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;21(1):2–9.

- Lanzkron S, Sawicki GS, Hassell KL, et al. Transition to adulthood and adult health care for patients with sickle cell disease or cystic fibrosis: current practices and research priorties. J Clin Transl Sci. 2018;2(5):334–342.

- Buchanan G, Vichinsky E, Krishnamurti L, et al. Severe sickle cell disease – pathophysiology and therapy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(1):S64–S67.

- Blinder MA, Vekeman F, Sasane M, et al. Age-related treatment patterns in sickle cell disease patients and the associated sickle cell complications and healthcare costs. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(5):828–835.

- van Beers EJ, van Tuijn CFJ, Mac Gillavry MR, et al. Sickle cell disease-related organ damage occurs irrespective of pain rate: implications for clinical practice. Haematologica. 2008;93(5):757–760.

- Vekeman F, Sasane M, Cheng WY, et al. Adherence to iron chelation therapy and associated healthcare resource utilization and costs in medicaid patients with sickle cell disease and thalassemia. J Med Econ. 2016;19(3):292–303.