Abstract

Background

Pimavanserin (PIM) is the only FDA approved atypical antipsychotic (AAP) for the treatment of Parkinson’s Disease Psychosis (PDP) while other off-label AAPs like quetiapine (QUE) are also used. Real-world comparative effects of PIM and QUE on health resource utilization (HCRU) may provide insights about their relative benefits.

Objectives

To examine annual HCRU among newly initiated PIM or QUE monotherapy among patients with PDP.

Methods

Retrospective analysis of 100% Medicare (Parts A, B, and D) claims of patients with PDP during 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2019 was conducted. Treatment-naive patients with first prescription for PIM or QUE from 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2018 were selected if they had ≥12-months continuous monotherapy and had no prior AAP use for ≥12-month pre-index. Post-index 12-month HCRU was compared between 1:1 propensity score matched (PSM) PIM or QUE cohorts. HCRU outcomes included: rates of all-cause and psychiatric-related inpatient hospitalizations by stay-type [i.e., long-term stays (LT-stays), short-term stays (ST-stays), skilled nursing facility stays (SNF-stays)], outpatient hospitalizations, emergency room (ER) visits, and office visits. Relative risk and 95% confidence intervals are reported [RR (95% CI)].

Results

A total of 842 and 7,116 were treated with PIM and QUE, respectively. Mean age and gender distribution were similar among both groups. After PSM, those on PIM (n=842) had significantly lower RR for all-cause: inpatient hospitalizations [RR=0.78 (0.70–0.87)], ST-stays [RR=0.75 (0.66–0.84)], SNF-stays [RR=0.64 (0.54–0.76)], and ER visits [RR=0.91 (0.84–0.97)] vs. QUE (n=842). PIM patients had slightly higher RR for all-cause office visits [RR=1.03 (1.01–1.05)] vs. QUE. Psychiatric-related inpatient hospitalizations were also lower for PIM vs. QUE: [RR=0.63 (0.48–0.82)] ST-stays [RR=0.61 (0.43–0.86)], SNF-stay [RR=0.69 (0.47–1.02)], and ER visits [RR=0.53 (0.37–0.76)].

Conclusions

In this analysis of PDP patients, PIM monotherapy resulted in nearly 22% and 37% lower all-cause hospitalizations and psychiatric-related inpatient hospitalizations compared to QUE.

Introduction

Parkinson Disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that is characterized by the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra. It is estimated that 572 per 100,000 residents aged 45 years or older have PDCitation1. The Parkinson Disease foundation reports that, by 2030, more than 1 million people in the United States will be diagnosed with PD, and 60,000 new cases being diagnosed each yearCitation2. Approximately 25%–40% of PD patients are known to develop Parkinson’s disease psychosis (PDP), which are commonly characterized by symptoms of hallucinations and delusionsCitation3–5. Additionally, the care associated with psychotic symptoms in PDP patients impose a significant healthcare utilization and cost burden as well as inflicting a tremendous burden to caregivers and family membersCitation6. In a sample of Medicare claims data from 2000 to 2010, patients with PDP had higher all-cause healthcare resource utilization and costs than those with only PDCitation7.

To date, a vast majority of the treatment options for PDP have mostly included off-label atypical antipsychotics (AAPs) such as quetiapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole. Some studies suggest that approximately 60–75% of PDP patients have been treated with quetiapine (QUE), despite an unfavorable risk of adverse events, some of which include increased risk of stroke, mortality, weight gain, and other extrapyramidal symptomsCitation8,Citation9. QUE is an atypical antipsychotic (AAP) agent approved for the treatment of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression; however, in recent years, it has been widely used off-label for the management of psychosis in parkinsonismCitation10. In 2016, pimavanserin (PIM) became the first FDA approved agent for the treatment of delusions and hallucinations associated with PDPCitation11. PIM is an AAP with selective 5-HT2A inverse agonist/antagonist properties that also binds lesser in extent to 5-HT2c receptors, however, has no binding affinity for dopaminergic, adrenergic, muscarinic, or histaminergic receptorsCitation12. In contrast to QUE, a phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial, has demonstrated the effectiveness of PIM in improving psychotic symptoms of PD, establishing PIM being well-tolerated, and has displayed no worsening of motor symptoms in patients with PDPCitation13,Citation14. Evidence-based reviews by expert panels of the Movement Disorder Society and the American Geriatrics Society also have recommended the use of PIM as a clinically useful agent for the treatment of PDP symptoms while QUE has been suggested to have modest and inconsistent clinical benefitsCitation12,Citation15.

While several clinical trials have established the safety profile of PIM on hallucinations and delusions, data from the real-world assessment in terms of healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) is often scarce. A recent study of PDP among the commercially insured as well as those covered under Medicare indicate that nearly 3 in 4 patients with PDP have been treated with QUECitation16. Despite the widespread off-label use of QUE for treatment of PDP, studies examining its effect in usual care settings are lacking. Additionally, given the advent of PIM as the only approved AAP by US FDA for the treatment of patients with PDP, comparative head-to-head studies are needed. Therefore, it is important to conduct real-world comparative analyses of PIM vs. QUE to better understand the impact of these therapies among patients with PDP. In this study we examined differences in health care resource utilization (HCRU) patterns (i.e. inpatient and outpatient hospitalizations, emergency room (ER) visits, and healthcare encounter (office) visits) among Medicare beneficiaries treated with PIM and QUE for PDP.

Materials and methods

Study design

A retrospective cohort analysis of treatment naïve PDP patients newly initiating PIM or QUE monotherapy was conducted using data from 100% sample of CMS Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries. Eligible PDP patient sample was identified using a combination of Parts A, B, and D pharmacy claims from 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2019. Subsequently, new PIM and QUE initiators were identified based on Part D claims during 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2018, to allow for at least 12 months lookback period (pre-index) and 12 months follow-up period (post-index). Our study was conducted in accordance with the CMS data use agreement that was established after New England Institutional Review Board review and approval. All analyses were conducted in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996. Given the observational nature of this database analysis, a STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology) checklist is also included in the Supplementary Appendix to demonstrate the compliance with standards for reporting.

Patient population

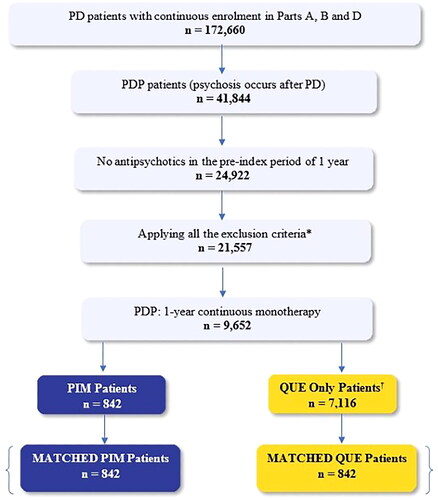

In this analysis, patients with PDP were identified based on medical claims for a PD diagnosis (ICD-9: 332.0, ICD-10: G20) plus one or more concurrent medical claims for the following psychosis related diagnosis: psychotic disorder with hallucination/delusions, psychosis, delusion disorder, visual disturbances, hallucinations (See Supplementary Table 1 for corresponding ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes). Patients with PDP who were started on PIM or QUE monotherapy for ≥12 months continuously (post-index) between January 2014 and December 2018 were included in the study sample. The index date was identified as the date of first prescription for PIM or QUE for the two study groups. Only patients without prior use of any AAP for at least 12-months prior to index date were included. PDP patients with a pre-index diagnosis of psychosis, secondary parkinsonism, delirium, other psychotic disorders, alcohol/drug-induced psychosis, schizophrenia, paranoia, or personality disorders, were also excluded from study population. A complete list of diagnosis codes used for the inclusion/exclusion criteria are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Patient selection criteria and attrition table is provided in .

Figure 1. Patient attrition diagram. Abbreviations. PD, Parkinson’s disease; PDP, Parkinson’s disease psychosis; PIM, pimavanserin; QUE, quetiapine. *Diagnosis of secondary Parkinsonism, delirium, other psychotic disorder, alcohol/drug-induced psychosis, schizophrenia, paranoia, or personality disorders. †Patients treated with other AAPs (n = 8,810) i.e. risperidone (n = 913), olanzapine (n = 446), and aripiprazole (n = 335) were removed to further obtain patients with QUE only (n = 7,116).

Covariates

The pre-index baseline characteristics including age, gender, race, region, clinical comorbidities, concomitant movement disorder medication (i.e. levodopa, carbidopa, levodopa/carbidopa) use, and coexisting insomnia or dementia status were examined during 12 months prior to index date. Clinical and individual comorbidities, as well as movement disorder medication (levodopa/carbidopa) were evaluated using the Elixhauser comorbidity index score for 12 months pre-index period.

Outcomes

HCRU outcomes related to any all-cause and psychiatric-related inpatient hospitalizations, ER visits, outpatient hospitalizations and health care provider office encounters (office visits) were analyzed. All-cause inpatient and outpatient hospitalizations ER visits, and office visits were defined as an admission or visits to a healthcare facility or a professional health care provider for any reasons. Psychiatric-related hospitalization or visits was defined as an admission/visit in any diagnosis field for any one of the psychotic disorders described in Supplementary Table 1. In Medicare claims, inpatient hospitalizations are further categorized into three types of admissions based on provider type/facility characteristics (i.e. facilities characterized by allowable length of stay): (1) short-term stay (ST-stay: any hospitalizations in a facility/hospital that provides care to patients that require an acute or critical setting following surgery, sudden sickness, injury, or flare-up of a chronic sickness); (2) long-term care stay (LTC-stay: hospitalizations in certified long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs) among patients who may transfer from intensive care units to LTACHs of stay >25 days upon admission; (3) skilled nursing facility stay (SNF-stay: hospitalizations that are longer than LTC-stays and may house patients for up to 100 days).

Propensity score matching

Patients newly initiating PIM or QUE were propensity score-matched in a 1:1 ratio to create a balanced sample. Propensity scores were calculated using multivariate logistic regression on patient age, gender, race, region, and 27 of the 31 Elixhauser comorbidity characteristics. Four other comorbidities such as psychosis, HIV, alcohol abuse, and substance abuse were not used in propensity score matching since patients with psychosis in the pre-index period were excluded in this analysis and data for patients with HIV, alcohol abuse and substance use may be suppressed by CMS to accommodate patient confidentiality, thus would not have allowed an appropriate method of matchingCitation17–20. An 8:1 Digit matching algorithm was utilized to perform the matching process in a greedy nearest neighbor fashion. Briefly, the algorithm matches PIM cases to QUE based on eight digits of the propensity score and for remaining unmatched cases, the algorithm continues sequentially down to one-digit matches, until no further matches can be made. The matching procedure used for this analysis has been described elsewhereCitation21. Covariate balance were assessed using standardized mean differences (SMDs) value of <0.1 between PIM and QUE beneficiaries. In our unmatched cohort prior to matching there are no covariates with missing data.

Statistical analysis

Baseline patient demographic and clinical characteristics such as gender (Male/Female), race (Unknown, White, Black, Other, Asian, Hispanic, American Native), region (Northeast, Midwest, West, South), Elixhauser comorbidities (Yes/No), were assessed using frequencies, proportions. Continuous variables such as age were reported as mean, standard deviation (SD), median, interquartile range (IQR) for both the matched and unmatched cohorts. Differences between PIM versus QUE were examined using chi-square tests for categorical measures, t-tests for parametric continuous outcomes and Wilcoxon-Rank sum tests for nonparametric continuous outcomes. Standardized rates and mean per-patient-per-year (PPPY) rates of all-cause hospitalizations, ER visits, outpatient and office visits were also assessed. Adjusted rates for all-cause and psychiatric-related inpatient and outpatient hospitalizations ER visits, and office visits, between PIM and QUE cohorts were analyzed using generalized linear models while controlling for baseline patient demographic, clinical characteristics, and comorbidities including baseline dementia and baseline insomnia. Relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated among the two groups and are reported. Unless otherwise specified, all p values were set to a threshold of p < .05 and all analyses were conducted using SAS Enterprise Guide Server 7.15 [SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC] via the CMS Virtual Research Data Center.

Results

Of the 9,652 patients who initiated continuous monotherapy for ≥ 12 months, 7,958 eligible patients with PDP met our study inclusion and exclusion criteria. Of these, 842 patients were newly treated with PIM and 7,116 newly treated with QUE. shows a study flow diagram of our study population. The average age of our pre-matched study sample was 77.4 (±7.2) and 78.1 (±7.7) for PIM and QUE, respectively (). After completing the 1:1 propensity score matching, there were 842 PIM patients matched to 842 QUE patients who were followed for 12 months. Patient demographic and baseline characteristics for PIM and QUE, before and after PS matching, are described in and . Among the matched PIM vs. QUE cohort, the median daily dose was 34 mg (IQR: 34, 34) and 38 mg during study follow-up period (IQR: 25, 50), respectively.

Table 1. Patient demographics: pre-matched and post-matched PIM vs. QUE groups.

Table 2. Baseline comorbidities, pre-matched and post-matched PIM vs. QUE groups.

In the matched sample, patients on PIM relative to QUE, displayed significantly lower relative risk for all-cause inpatient hospitalizations [RR = 0.78 (95 CI%: 0.70–0.87)], all-cause short-term stays [RR = 0.75 (95% CI: 0.66–0.84)], all-cause SNF stays [RR = 0.64 (95% CI: 0.54–0.76)], and all-cause ER visits [RR = 0.91 (95% CI: 0.84–0.97)]. All comparative HCRU results between PIM and QUE are described in .

Table 3. All-cause and psychiatric HCRU, among matched PIM vs. QUE.

Similar trends were seen when we examined relative risk of psychiatric-related hospitalizations. Patients with PIM had significantly lower rates of psychiatric-related inpatient hospitalizations [RR = 0.63 (95% CI: 0.48–0.82)], psychiatric-related short-term stays [RR = 0.61 (95% CI: 0.43–0.86)], and psychiatric-related ER visits [RR = 0.53 (95% CI: 0.37–0.76)]. Although rates for psychiatric-related SNF and outpatient hospitalizations were also lower in PIM compared to QUE, these differences were not statistically significant.

Rates of all-cause health care provider office visits and psychiatric-related office visits, however, were significantly higher in the PIM group compared to QUE, [RR = 1.03 (95% CI: 1.01–1.05)] and [RR = 1.73 (95% CI: 1.55–1.94)], respectively.

displays the mean all cause PPPY HCRU among beneficiaries on continuous PIM monotherapy compared with those on continuous QUE monotherapy. Relative to those on QUE, patients on PIM displayed a significantly lower standardized mean number all-cause of any inpatient hospitalizations (0.94 [±1.66)] vs. 1.44 [±2.09], p < .05), short term stays (0.59 [±1.09] vs. 0.85 [±1.30], p < .05), SNF stays (0.28 [±0.66] vs. 0.51 [±0.94], p < .05), and ER visits (1.27 [±1.57] vs 1.73[±2.69], p < .05) over one year follow-up. Standardized mean number of outpatient hospitalizations and office visits were also lower in PIM compared to QUE, but the differences were not statistically significant across the two groups.

Table 4. Mean all-cause PPPY HCRU, matched PIM vs. QUE cohorts.

Discussion

This analysis is the first to compare real-world HCRU patterns, specifically all-cause and psychiatric hospitalizations, ER visit differences between PIM versus QUE. Distribution of mean age and ratios of males to females, and race were comparable across the two cohorts (PIM and QUE) after matching. PIM cohort, however, had lower rates of patients with coexisting insomnia or dementia and lower comorbidity scores compared to QUE. In both PIM and QUE cohorts, over 4 in 5 patients (88% of PIM and 80% of QUE patients) were treated with movement disorder (e.g. levodopa/carbidopa) at index-date. The results of this real-world Medicare claims study demonstrate that patients with PDP on PIM monotherapy compared to those on QUE monotherapy had significantly lower all-cause and psychiatric related inpatient hospitalizations and ER visits. Patients on PIM displayed significantly lower incident rates of all-cause inpatient hospitalizations of all type, including short-term care and skilled nursing facility stays. Similarly, rates of all-cause ER visits among PIM treated patients were lower compared to patients treated with QUE. However, rates of all-cause outpatient office visits among PIM patients were significantly higher. The HCRU results observed here in this analysis may be indirectly correlated to and consistent with the Movement Disorder Society (MDS) evidence-based review findings about the clinical efficacy of AAP treatments for non-motor symptomsCitation15. According to them, quetiapine demonstrated moderate and inconsistent effects in improving hallucinations and delusions associated with PDP. In contrast, the recommendations indicate that PIM is clinically useful for treating psychosis symptoms among patients with PDPCitation15. The apparent increase in outpatient office visits while inpatient hospitalizations and ER visits were lower may be explained by a few possibilities. First, it is possible that PIM treated patients have potentially greater frequency of physician monitoring and follow-up visits, presumably due to more of the PIM remaining in an ambulatory setting rather than transferring to LTC/NH settings. Second, the low median dose of QUE suggests that it may have been prescribed for insomnia or dementia rather than PDP resulting in a lower likelihood of QUE patients needing to make office visits. In this analysis, median daily dose of quetiapine was found to be 38 mg/day (IQR: 25,50mg) potentially confirming our hypothesis that PDP patients receiving QUE may have been prescribed it for reasons other than PDP. In fact, the significantly higher proportion of dementia or insomnia in the pre-matched and post-matched QUE cohort and low median daily dosage of QUE support this possibility. Also, some neurologists use QUE to treat both sleep issues as well as PDP. Current studies also indicate widespread use of low-dose quetiapine to treat insomnia globallyCitation22–24. Future investigations of PIM vs QUE comparisons should also consider comparing PIM patients with patients who are prescribed a therapeutic dose range of QUE for the treatment of PDP symptoms. Chen et al. have suggested that while QUE has not been approved for the treatment of PDP, a daily dose range of 50–150 mg may be recommended for the treatment of PDP symptomsCitation6,Citation10. Third, it is also possible that PIM treated patients spend more time in the community, as demonstrated by the fewer LTC hospitalizations and SNF stays, potentially resulting in greater office visits.

While our study cohorts were required to be on continuous monotherapy, it is possible that medication adherence (i.e. prescription taking behavior) may be adversely impacted among those diagnosed with dementia in an outpatient setting. Additionally, direct safety and tolerability data that impact adherence are also unavailable for this kind of retrospective claims database study. Therefore, the extent to which actual adherence differences between these cohorts may impact subsequent HCRU is unknown.

Overall, these results suggest that future investigations should further examine the association between drivers of psychiatric episode occurrence such as frequency and severity of psychiatric symptoms (i.e. hallucinations and delusions) and rates of psychiatric hospitalizations and ER visits as well as hospital length of stays. Overall, results of this analysis are generalizable to the overall population with PDP since over 9 in 10 patients with PDP are over 65 and are likely to be covered under Medicare insurance.

Limitations

As with any research, this study is subject to the limitations of any administrative claims data analysis. Since claims data are primarily used for billing and reimbursement purposes, coding errors may have resulted in either underestimation or overestimation of the cohort sample. To the extent that our study utilized confirmatory diagnostic claims to identify patient sample, these errors have been minimized. Additionally, administrative claims do not have any clinical outcomes information. Therefore, analyses such as this cannot account for unobservable patient characteristics, facility characteristics, or other factors that may bias the results. Furthermore, the study also did not examine the association between prescriber type and consequent impact on HCRU outcomes related to inpatient, outpatient hospitalizations, and office visits were not examined. Therefore, future investigations examining the association between prescriber type and outcomes may be warranted. In this analysis, we did not control for variables in the causal pathway, such as baseline HCRU, to avoid masking true differences in HCRU outcomes between the treatment cohortsCitation25. However, literature also suggests that baseline HCRU is a well-known predictor of subsequent HCRU. Given this, it is possible that some of the differences may be attributable to baseline HCRU differences. Therefore, future studies should examine the role of baseline HCRU on post-index follow-up HCRU.

We utilized PS matching to ensure balanced cohorts, however, it is possible there may be a risk of overadjustment given some covariates overlap with PSM criteria or that residual confounding may exist. Given the large standard deviations in HCRU outcomes, it is possible that inter-individual variability among patients may be skewed by heavy service users. Additionally, our study relied on data encompassing the entire population of Medicare beneficiaries in the United States, thus providing a 100% sample from 2013 to 2019. Therefore, no power calculations were performed for this study. This approach ensures the generalizability of the study sample to overall Medicare population, as it includes all patients covered by Medicare during that period. It is also possible that the inclusion of patients initiating QUE during 2014–2015 for the QUE cohort (i.e. before FDA approval of PIM in 2016) may have created a bias between the PIM and QUE cohorts. However, to the best of our knowledge, off-label AAP prescribing patterns have not changed since the advent of PIM in 2016 and it is potentially unlikely to introduce any temporal bias between the cohorts.

Additionally, our analysis could not control for underlying PD or PDP severity since severity cannot be defined in claims data. Despite PS matching, PIM patients had a larger number of patients with no difference in majority of comorbidities compared to QUE cohort. This finding suggests that PIM and QUE patient groups may have had a different underlying severity distribution that we could not fully account for. Low QUE median dose and the higher proportion of patients in the QUE sample suggest the possibility of it being prescribed for insomnia rather than PDP which may likely bias the results, despite adjusting for coexisting insomnia in the inferential analysis. Future comparative analysis of PIM vs QUE may include patients of therapeutically equivalent dose of quetiapine based on chlorpromazine equivalents or some form of defined therapeutic daily dose. Notwithstanding the above, this analysis represents a significant addition to the body of neuropsychiatric literature about the real-world benefits of PIM compared to QUE.

Conclusions

This analysis evaluating the HCRU pattern among Medicare patients with PDP that are treated with PIM vs. QUE showed a significantly lower incidence rate of inpatient hospitalizations and ER visits for all-cause or psychiatric-related reasons. On the other hand, small but significantly higher rates of outpatient office visits were reported for PIM treated patients compared to QUE patients. Overall, these results show the real-world HCRU benefits of PIM vs. QUE as it relates to hospitalization by stay-type and ER visit outcomes among patients with PDP. The results of our research are consistent with a recent publication that demonstrated a 30% one-year lower risk of hospitalizations among PIM vs QUE usersCitation26. Future analysis examining the comparative effects of both medications, in terms of other clinical outcomes such as falls and fractures, may be warranted to understand the potential reasons for lower HCRU among PIM compared to QUE patients.

Transparency

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Krithika Rajagopalan is a current employee of Anlitiks Inc., a company that received funding from Acadia Pharmaceuticals to conduct this study. Nazia Rashid and Dilesh Doshi are employees of Acadia Pharmaceuticals. A reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed that they received manuscript or speaker’s fees from Astellas, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Elsevier Japan, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Kyowa Yakuhin, Lundbeck Japan, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Nihon Medi-Physics, Novartis, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Shionogi, Shire, Sumitomo Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Tsumura, Viatris, Wiley Japan, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin, and research grants from Eisai, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Shionogi and Sumitomo Pharma. The other peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (22 KB)Acknowledgements

Daksha Gopal, employee of Anlitiks conducted parts of the analysis and provided medical writing and editorial support for the manuscript. Safiuddin Shoeb Syed, employee of Anlitiks provided editorial support for the manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Marras C, Beck JC, Bower JH, et al. Prevalence of Parkinson’s disease across North America. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2018;4:21.

- Parkinsons Foundation. Prevalence and incidence. Available from: https://www.parkinson.org/understanding-parkinsons/statistics/prevalence-incidence

- Factor SA, Scullin MK, Sollinger AB, et al. Cognitive correlates of hallucinations and delusions in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 2014;347(1-2):316–321.

- Ffytche DH, Creese B, Politis M, et al. The psychosis spectrum in Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13(2):81–95.

- Aarsland D, Larsen JP, Tandberg E, et al. Predictors of nursing home placement in Parkinson’s disease: a population-based, prospective study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(8):938–942.

- Chen JJ, Hua H, Massihi L, et al. Systematic literature review of quetiapine for the treatment of psychosis in patients with parkinsonism. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;31(3):188–195.

- Hermanowicz N, Edwards K. Parkinson’s disease psychosis: symptoms, management, and economic burden. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(10 Suppl):s199–s206.

- Connolly B, Fox SH. Treatment of cognitive, psychiatric, and affective disorders associated with Parkinson’s disease. Neurotherapeutics. 2014;11(1):78–91.

- Zahodne LB, Fernandez HH. Pathophysiology and treatment of psychosis in Parkinson’s disease: a review. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(8):665–682.

- Chen JJ. Treatment of psychotic symptoms in patients with Parkinson disease. Ment Health Clin. 2017;7(6):262–270.

- Acadia Pharmaceuticals. Nuplazid® (pimavanserin) prescribing information. San Diego, CA: Acadia Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2018.

- By the American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227–2246.

- Hawkins T, Berman BD. Pimavanserin: a novel therapeutic option for parkinson disease psychosis [published correction appears in Neurol Clin Pract. 2017 Aug;7(4):282]. Neurol Clin Pract. 2017;7(2):157–162.

- Cummings J, Isaacson S, Mills R, et al. Pimavanserin for patients with Parkinson’s disease psychosis: a randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial [published correction appears in Lancet. 2014 Jul 5;384(9937):28]. Lancet. 2014;383(9916):533–540.

- Seppi K, Ray Chaudhuri K, Coelho M, et al. Update on treatments for nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease-an evidence-based medicine review [published correction appears in Mov Disord. 2019 May;34(5):765]. Mov Disord. 2019;34(2):180–198.

- Kumar S, Rashid N, Doshi D, et al. ER visits and hospitalizations among patients treated with pimavanserin or other-AAPs for Parkinson’s disease psychosis: analysis of Medicare beneficiaries [abstract]. Mov Disord. 2022;37(suppl 1). Available from: https://www.mdsabstracts.org/abstract/er-visits-and-hospitalizations-among-patients-treated-with-pimavanserin-or-other-aaps-for-parkinsons-disease-psychosis-analysis-of-medicare-beneficiaries/

- Sewell DD, Jeste DV, Atkinson JH, et al. HIV-associated psychosis: a study of 20 cases. San Diego HIV neurobehavioral research center group. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(2):237–242.

- Collins RL, Beckett MK, Burnam MA, et al. Mental health and substance abuse issues among people with HIV: lessons from HCSUS. Santa Monica (CA): RAND Corporation; 2007. Available from: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9300.html.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Co-occurring disorders and other health conditions; 2022 Apr 21 [updated 2022 Apr 21; cited 2022 Jul 29]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/medications-counseling-related-conditions/co-occurring-disorders

- Sterling S, Chi F, Hinman A. Integrating care for people with co-occurring alcohol and other drug, medical, and mental health conditions. Alcohol Res Health. 2011;33(4):338–349.

- Rajagopalan K, Rashid N, Kumar S, et al. Health care resource utilization patterns among patients with Parkinson’s disease psychosis: analysis of Medicare beneficiaries treated with pimavanserin or other-atypical antipsychotics. J Med Econ. 2023;26(1):34–42.

- Pringsheim T, Gardner DM. Dispensed prescriptions for quetiapine and other second-generation antipsychotics in Canada from 2005 to 2012: a descriptive study. CMAJ Open. 2014;2(4):E225–E232.

- Debernard KAB, Frost J, Roland PH. Quetiapine is not a sleeping pill. Kvetiapin er ikke en sovemedisin. Tidsskr nor Laegeforen. 2019;139(13). DOI:10.4045/tidsskr.19.0205

- Duncan D, Cooke L, Symonds C, et al. Quetiapine use in adults in the community: a population-based study in Alberta, Canada. BMJ Open. 2016;6(3):e010861.

- Diehr P, Yanez D, Ash A, et al. Methods for analyzing health care utilization and costs. Annu Rev Public Health. 1999;20:125–144.

- Alipour-Haris G, Armstrong MJ, Okun M, et al. Comparison of pimavanserin versus quetiapine for hospitalization and mortality risk among Medicare beneficiaries with Parkinson’s disease psychosis. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2023;10(3):406–414.