?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Aims

To assess, within the Italian healthcare system, the cost-effectiveness of baricitinib versus dupilumab, both in combination with topical corticosteroids (TCS), in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD) who are eligible for but have failed, have contraindications to, or cannot tolerate ciclosporin.

Materials and methods

Using the perspective of the Italian healthcare payer, direct medical costs associated with each intervention were estimated over a lifetime horizon. A Markov cohort model utilized the proportions of patients with ≥75% improvement Eczema Area and Severity Index obtained from clinical trials. Health outcomes were evaluated in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) to assess the cost effectiveness of baricitinib against a willingness-to-pay threshold of €35,000 per QALY gained.

Results

In the base case, with secondary censoring applied, patients treated with dupilumab or baricitinib, in combination with TCS, accumulated total costs of €135,780 or €129,586, and total QALYs of 18.172 or 18.133, respectively. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of dupilumab versus baricitinib was estimated at €160,905/QALY.

Limitations

Core assumptions were needed to extrapolate available short-term clinical trial data to lifelong data, adding uncertainty. Benefits of baricitinib seen in clinical trials and not assessed in dupilumab clinical trials were not included. Discontinuation rates for each treatment were derived from different sources potentially introducing bias. Results may not be generalizable to other populations.

Conclusions

This cost-effectiveness analysis shows that, from the Italian healthcare payer perspective, in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe AD who have experienced failure on, are intolerant to, or have contraindication to ciclosporin, dupilumab cannot be considered cost-effective when compared with baricitinib. Given its oral administration, favorable risk/benefit profile and lower acquisition cost compared with dupilumab, baricitinib may offer a valuable, cost-effective treatment option—after failure on conventional systemic agents—for patients with moderate to severe AD in Italy.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Baricitinib is the first oral systemic treatment for patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD). The drug was effective for treating patients with AD in clinical trials, producing improvements in skin inflammation, itch, sleep disturbances due to itch and skin pain, as well as the quality of life of patients. However, it is important to ensure that healthcare funds are well spent. We therefore compared the cost-effectiveness of baricitinib, with another new systemic treatment for AD, dupilumab, (both in combination with topical corticosteroids) in patients with moderate to severe AD who are eligible for but have failed or are unable to take ciclosporin, in Italy. We found that using dupilumab to treat these patients with AD cost more than using baricitinib, although dupilumab was more effective. Combining these considerations showed that the cost of obtaining the additional benefit from dupilumab over baricitinib was not cost-effective for the Italian healthcare system. Baricitinib may be a better treatment option because it is given orally, has a favorable balance between the risks and benefits of treatment, and costs less than dupilumab.

Introduction

Moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD) can cause widespread inflamed skin all over the body and constant itching, with areas of affected skin occasionally becoming infected.Citation1–3 AD causes the highest number of disability-adjusted life years among skin diseases,Citation4 and patients with moderate to severe disease often experience unbearable symptoms that interfere with practically every daily activity.Citation3,Citation5–7 An Italian study estimated the total annual financial burden of the disease to be €4,284 per patient,Citation8 and a recent United States study estimated the average lifetime cost of usual care with emollients for moderate to severe AD at approximately $271,450 per patient.Citation9 However, limited treatment options are available for these patients.

Topical therapies are the backbone of AD treatment.Citation10,Citation11 However, patients with moderate to severe AD who have been unable to achieve adequate disease control with first line topical corticosteroids (TCS), with or without adjunct topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI) are candidates for additional therapies, such as phototherapy, high-potency TCS, and systemic treatment.Citation10,Citation11 Ciclosporin is the only conventional systemic therapy approved in the European Union (EU), and although efficacious, it has a narrow therapeutic index and monitoring of renal function and blood pressure is recommended, as use can lead to renal impairment and increased blood pressure.Citation11 Current AD guidelines list off-label use of systemic corticosteroids (only as rescue therapy), methotrexate, and azathioprine as alternative therapeutic options; however, these therapies are limited by low quality evidence of efficacy, various contraindications, and, in some instances, severe toxicity.Citation11

In 2017, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) approved dupilumab,Citation12 an immunoglobin (Ig) G4 monoclonal antibody that inhibits interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13, for subcutaneous injection, with or without TCS, for patients with moderate to severe AD. Dupilumab was the first new treatment approved for moderate to severe AD since 2002.Citation12,Citation13 However, not all patients achieve disease control with this drug,Citation14 injections cause anxiety for some patients, with injection site reactions occurring in 8 to 19% of patients,Citation14,Citation15 and conjunctivitis occurring more frequently than with placebo in clinical trialsCitation14 and within 16 weeks of starting treatment in 34% of patients in long-term registries.Citation16

Baricitinib, the first oral systemic treatment for moderate to severe AD, was approved by the EMA for adult patients who are candidates for systemic therapy in 2020.Citation17 Baricitinib inhibits Janus Kinase (JAK) 1 and JAK2 with high selectivity, and targeted and reversible inhibition, suggesting it affects several cytokines involved in AD pathogenesis.Citation18 Three Phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials have confirmed the efficacy of baricitinib (e.g. improvements in skin inflammation, itch, sleep disturbances due to itch and skin pain), when used as monotherapy or in combination with TCS, in the approved patient population.Citation19,Citation20 A further Phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, trial confirmed the efficacy of baricitinib in combination with TCS in patients with prior failure of ciclosporin, or intolerance or contraindication to ciclosporin.Citation21 Furthermore, rapid, and sustained efficacy has been observed for many patient-reported outcomes, demonstrating the important impact baricitinib may have on patients’ quality of life.Citation19–21

In this analysis, we assessed the cost-effectiveness of baricitinib, as compared with dupilumab, both in combination with TCS therapy, in patients with moderate to severe AD who are eligible for but have failed, have contraindications to, or cannot tolerate ciclosporin, within the context of the Italian healthcare system.

Methods

General

Target population

The target population were adults (≥18 years) who had been diagnosed with moderate to severe AD for at least 12 months, had an inadequate response to existing topical medication within the last 6 months, were eligible for systemic therapy, and had experienced failure to ciclosporin, or were intolerant to, or had a contraindication to ciclosporin. The target population was selected as it reflected the population identified by the Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA) as eligible for treatment with the comparator, dupilumab.Citation22

Study perspective

Estimates of direct medical costs associated with each intervention were derived from the perspective of the Italian healthcare payer. These included the costs of the comparators (i.e. baricitinib plus TCS and dupilumab plus TCS), concomitant topical treatments, and rescue medications to treat flares often used in the management of moderate to severe AD, ongoing administration and monitoring costs, costs associated with adverse events (AEs), and the costs of best supportive care (BSC) for non-responders.

Comparators

Dupilumab was selected as the comparator for baricitinib as it is the only drug currently reimbursed in Italy for the treatment of moderate to severe AD after cyclosporin failure. In the absence of head-to-head clinical study data, new AIFA guidelines on the pricing and reimbursement of medicines (which came into effect March 2021) require a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) comparing any new drug with the appropriate comparator(s) in the relevant indication to be included in the submission dossier.Citation23 Both baricitinib and dupilumab were assumed to be administered with adjunct emollients and TCS,Citation10,Citation11,Citation21 in line with standard clinical practice. Dose regimens for both comparators reflect the main regimens recommended for AD in the EU: baricitinib 4 mg/day administered orallyCitation24 and dupilumab 600 mg starting dose followed by 300 mg once every 2 weeks administered by subcutaneous injection.Citation25

Time horizon

A lifetime horizon was adopted for the base case given the Italian healthcare payer perspective, as this was aligned with the earlier dupilumab submission.Citation7,Citation26 An alternative 3-year time horizon was explored in a scenario analysis, as this was considered long enough to capture all effects of both comparator treatments on benefits and costs.

Discount rate

Both costs and health outcomes were discounted at an annual rate of 3%, as recommended by Italian pharmacoeconomic guidelines.Citation23 Sensitivity analyses explored annual discount rates between 0% and 5%, as per Italian guidelines.

Censoring

Secondary censoring (i.e. censoring of data after permanent study drug discontinuation) was used for all utility and efficacy variables included in the models. This censoring method is considered to be reflective of clinical practice.

Outcomes

Choice of outcomes

The health outcomes of each intervention were evaluated in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) to assess the cost effectiveness of baricitinib against the willingness-to-pay threshold of €35,000 per QALY gained. This threshold is the approximate mid-value of published ranges for Italy of €12,000–€60,000.Citation27

Measurement of effectiveness

Estimates of clinical effectiveness were derived from an indirect treatment comparison (ITC) of baricitinib 4 mg/day versus dupilumab 300 mg once every 2 weeks (following a loading dose of 600 mg), in combination with TCS, in adult patients with moderate to severe AD who had failed, had contraindications to, or were intolerant of both topical agents and ciclosporin (ITC population B).Citation28 The ITC used Bucher methodologyCitation29 for meta-analysis of data when more than one study contributed, and placebo was used as the common comparator.

Relative efficacy was calculated as relative risk versus placebo for all outcomes, based on primary and secondary endpoints common across trials, including the proportion of patients with ≥50%, ≥75%, or ≥90% improvement Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI50, EASI75, EASI90) at Week 16, with missing data accounted for by non-responder imputation.Citation28 Clinical trials included in the ITC population B were BREEZE-AD4 (NCT03428100) for baricitinibCitation21 and LIBERTY AD CAFÉ (NCT02755649) for dupilumab.Citation30 Estimates of clinical effectiveness for BSC were derived from the placebo response rate in BREEZE-AD4.

Treatment response for the CEA base case was defined as an EASI75 response at the end of the induction period, measured using secondary censoring (). An alternative definition of treatment response, EASI50, was explored in sensitivity and scenario analyses.

Table 1. Outcomes—base case model inputs.

Responders were assumed to enter a maintenance phase, during which patients could discontinue treatment. Maintenance phase discontinuation rates for baricitinib and BSC were derived from the BREEZE-AD4 study. Source study permanent discontinuation rates between Week 0 and Week 52 (representing all-cause discontinuation; i.e. discontinuation of treatment due to lack of long-term efficacy, adverse event, patient or physician preference) were converted into discontinuation rates for the 36-week timeframe; that is, the probability of treatment discontinuation between the end of the induction period (time of response assessment; Week 16 in base case) and Week 52 (). The rate for dupilumab was derived from a real-world persistence study,Citation31 and was based on persistence at 12 months, with conversion to the appropriate timeframe (36 weeks). Loss of response was assumed to occur at a continuous and constant rate, and loss of response led to treatment discontinuation.

Annual probabilities of discontinuation after 52 weeks, representing the annual rates at which patients discontinue baricitinib or dupilumab each year due to lack of long-term efficacy, adverse events, patient or physician preference, were applied to patients in the maintenance health state starting in the second year of the model. These probabilities were derived as follows (): for dupilumab, a probability of 22.7% was set based on the abovementioned real-world persistence study,Citation31 and for baricitinib, post hoc analysis was performed on the long-term extension phase of the BREEZE-AD4 study ranging from Week 52 to Week 104. Patients were included if they started the trial receiving baricitinib 4 mg at baseline and remained on the same treatment after re-randomization after 52 weeks. As no similar analysis was possible for the placebo arm of the BREEZE-AD4 study (most patients had been re-randomized to baricitinib 2 mg or 4 mg treatment), annual all-cause discontinuation data (Week 0–52) were used for BSC. Patients who discontinued baricitinib or dupilumab were switched to BSC.

The average number of flares per patient per year was assumed to be eight with BSC and in non-responders,Citation32 and three while patients were receiving baricitinib or dupilumab; the average duration of a flare was assumed to be 15.2 days. AEs included were based on the most frequent and serious reported for each treatment, and derived from 16-week data from the BREEZE-AD4 study, rescaled to annual probabilities, for baricitinib, and from annual probabilities from National Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Technology Assessment (TA) 534 for dupilumab and BSC (). The risk of AEs was assumed to remain constant over the treatment duration, and AEs were not modelled as separate health states, rather AE rates and cost consequences accumulated in each cycle of treatment.

Age-adjusted mortality was stratified by sex and based on Italian Life Tables,Citation33 with no adjustment for AD-specific mortality. Gender-specific rates were combined to a blended rate based on the BREEZE-AD4 trial population gender proportions.

Measurement and valuation of preference-based outcomes

Utility values, baseline, and change from baseline at Week 16 based on observed and secondary censored responder criteria (e.g. EASI75), were derived directly from the BREEZE-AD4 study population, using linear repeated measurement models with utility values as dependent variables and response levels (using secondary censoring) as independent variables. Health state utility values were calculated by mapping EQ-5D-5L onto EQ-5D-3L response levels,Citation34 which were then valued against the Italian value set.Citation35

Given the base case lifetime horizon and the expectation that health utility declines with age, an annual adjustment factor for age, derived from United Kingdom (UK) data, was included in the model.Citation36 The annual adjustment factor Y enters the model multiplicatively and is derived using the following formula, where [38.2] is the mean age of the patients in the Phase 3 baricitinib clinical trials and [0.903] the overall utility at baseline age:

Included AEs were generally mild and transient, and generally balanced between treatment arms. No significant decrement to health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was expected due to AEs. Therefore, AE disutilities were not incorporated to avoid double counting, in line with previous AD economic assessments.Citation7,Citation37

Costs

Estimating resource use and costs

summarizes all cost inputs included in the model. Drug acquisition costs for baricitinib and dupilumab were derived from both the Compendio Farmadati and the Information Hospital Service (IHS) database,Citation38,Citation39 and calculated based on the cost per unit of each treatment and the required number of units per cycle for the approved AD regimens (Supplementary material Table S1). The cost of BSC, assumed to consist of TCS (clobetasol), was also derived from Compendio Farmadati, and calculated based on the pack cost and recommended daily dose (3 g/day)Citation38,Citation40 (Supplementary material Table S2). Patients receiving BSC were assumed not to accrue any drug acquisition costs during BSC response to avoid double counting costs with concomitant background TCS medication.

Table 2. Costs—summary of base case model inputs.

Costs of concomitant medication (bathing and emollient products, and background TCS) were derived from Compendio FarmadatiCitation38 (Supplementary material Table S3). Costs of rescue medications for flares, often required due to the relapsing remitting nature of AD, were based on five potential treatment options (with weight-based doses calculated based on the mean weight of patients in the BREEZE-AD4 studyCitation21) and derived from Compendio FarmadatiCitation38 (Supplementary material Table S4).

Resource use related to the administration and monitoring of treatment during induction and maintenance, which varied due to the differences in modes of action and administration routes of the comparators, was aligned with published Italian sources, and associated unit costs were derived from published Italian sourcesCitation8,Citation16,Citation41–46 (Supplementary material Table S5). Resource use and associated costs in the BSC non-response state, which comprised physician visit costs and the costs of other resource use for ongoing management, concomitant medication costs and the cost of rescue medication for flares, were derived from published Italian sourcesCitation8,Citation16,Citation38,Citation41–44,Citation47 (Supplementary material Table S6).

Costs associated with AEs were derived from the Italian Ministry of Health,Citation43 the Italian Diagnosis Related Groups (DRG)Citation48,Citation49 and NICE TA534Citation7 (Supplementary material Table S7).

Currency, price date, and conversion

Costs were calculated in 2020 Euro, with no adjustment for time.

Model

Choice of model

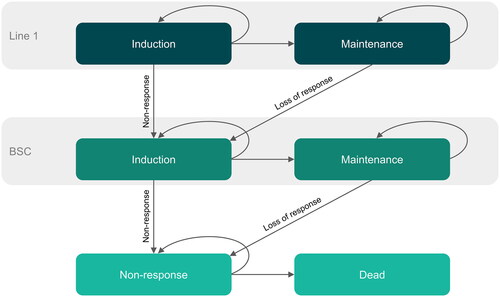

A Markov cohort model was built with four health states: induction, maintenance, non-response, and death (). It was programmed to facilitate pairwise comparisons of treatments as well as the implementation of different lengths of induction periods depending on treatment, with the same structural framework as the NICE TA534Citation7 and United States Institute for Clinical and Economic ReviewCitation50 models identified in a systematic literature review of cost-effectiveness model structures adopted in previous analyses for treatments of AD. A cycle length of 4 weeks (28 days) was sufficiently short to capture variations in costs and benefits resulting from changes in treatment.

Figure 1. Markov cohort model structure.

*Arrows to the Dead health state removed for simplification; Dead can be reached from any other health state at any time.

Treatment was dichotomized into two periods (induction and maintenance) as per other cost-effectiveness models undertaken in AD.Citation7,Citation37 A tunnel state framework was implemented in the induction period to reflect patients’ stay on treatment (baricitinib, dupilumab, or BSC) until first response assessment at 16 weeks (i.e. trial induction treatment period). Patients who responded to treatment at the end of the induction period remained on treatment by moving to the maintenance period. For patients on maintenance treatment, it was assumed that the level of response was constant at the level observed at the end of the induction period. Patients remained in this maintenance period until they transitioned to the next treatment in the sequence (i.e. BSC) or to non-response (i.e. after loss of response to BSC). Patients who did not respond to treatment at the end of the induction period transitioned to the BSC induction phase. Patients transitioned to the non-response health state when they lost response to BSC. Death was possible from every state.

Model assumptions

The model included a number of assumptions () including that only EASI75 responders continued treatment beyond 16 weeks; on average, patients maintained the level of response achieved at the end of the induction period until they discontinued treatment; patients with an initial response at Week 16 but without a response at Week 52 discontinued treatment at a continuous and constant rate between 16 and 52 weeks; patients in the non-response health state were assumed to remain in that state until the end of the model or death; and the risks of AEs remained constant over the treatment duration. In addition, health state utility values were derived from a baricitinib clinical trial capturing the impact of baricitinib and BSC on utility; although, given the different modes of action and routes of administration for baricitinib and dupilumab, the utility values may not reflect all AEs associated with dupilumab. It was also assumed that health utility values decline with age and that patients had 100% treatment adherence.

Table 3. Key model assumptions.

Analytical methods

A half-cycle correction was not included in the model due to the short cycle length (4 weeks). However, given the different time references for model inputs (e.g. annual [maintenance] and per 16-week period [induction]), variables were rescaled to 4-week durations. Probabilities (e.g. annual) were converted to an instantaneous rate and then converted back to the desired length probability (e.g. 4-week) as follows:

For absolute inputs (e.g. annual number of flares), linear conversions were applied by dividing the value to be adjusted by the number of days per year that the input was referring to, for example, 4-week frequency = annual frequency * (28/365.25).

Response data were calculated using non-responder imputation to account for missing data. Utility values were determined using linear repeated measurement models with utility as the dependent variable and response levels (using secondary censoring) as independent variables.

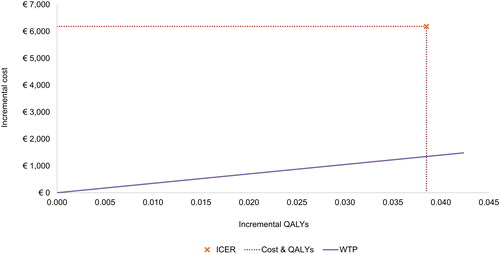

Base case results are presented as total and incremental deterministic costs and QALYs for dupilumab (followed by BSC) and baricitinib (followed by BSC), and the pairwise incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for dupilumab (followed by BSC) versus baricitinib (followed by BSC). A cost-effectiveness plane illustrates the base case results in the context of the Italian payer willingness-to-pay threshold.

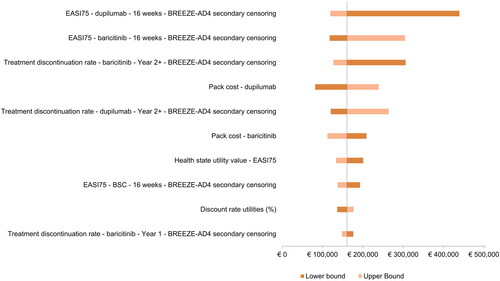

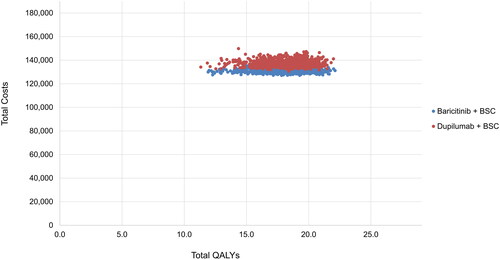

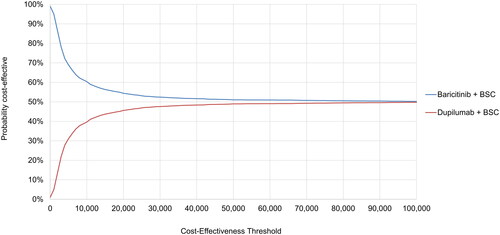

One-way sensitivity analysis (OWSA) was performed to consider the influence of individual parameters on model outputs, using pre-specified upper and lower limits for pre-selected parameters (Supplementary material Table S8); results are presented in the form of a Tornado diagram that includes the 10 most influential variables. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) was undertaken to address uncertainty around the means of input parameters by assigning appropriate distributions around the means (Supplementary material Table S9); results are presented as probabilistic mean costs and QALYs, with a scatterplot of individual simulations on the cost-effectiveness plane and a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve, both generated using 3,000 simulations of the PSA.

Scenario analyses were run to explore the impact of the assumptions and structural uncertainty of the model (). Results are presented as total and incremental deterministic costs and QALYs for baricitinib (followed by BSC) and dupilumab (followed by BSC), total life years for each treatment, and the pairwise ICER for dupilumab versus baricitinib.

Table 4. Scenario analyses.

Results

Incremental costs and outcomes

In the base case, in the BREEZE-AD4 study population (patients with moderate to severe AD who were eligible for systemic therapy and had experienced failure to ciclosporin, or were intolerant to, or had a contraindication to ciclosporin), dupilumab and baricitinib, in combination with TCS, accumulated total costs of €135,780 and €129,586, and total QALYs of 18.172 and 18.133, respectively (). The ICER of dupilumab versus baricitinib was estimated at €160,905/QALY. As seen in the cost-effectiveness plane shown in , this ICER is above the willingness-to-pay threshold of €35,000/QALY in Italy.Citation27

Figure 2. Base case results—cost effectiveness plane (dupilumab vs. baricitinib). ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; QALY, quality-adjusted life year; WTP, willingness-to-pay.

Table 5. Deterministic base case results.

Characterizing uncertainty

The 10 most influential variables in the OWSA are displayed in . In this diagram, each bar represents the impact of uncertainty in an individual variable on the ICER. The five variables with the largest impact on the ICER were the dupilumab and baricitinib EASI75 responses, the year 2+ treatment discontinuation rate for baricitinib, the dupilumab pack cost, and the year 2+ treatment discontinuation rate for dupilumab. All other variables had minimal effect.

Figure 3. One-way sensitivity analysis results—Tornado diagram (dupilumab vs. baricitinib). Secondary censoring, that is censoring of data after permanent study drug discontinuation, was applied to treatment outcomes. BSC, best supportive care; EASI75, 75% improvement Eczema Area and Severity Index.

A summary of the results of the PSA is presented in along with a scatterplot of total costs and QALYs in , and a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve in . The results of the PSA align well with the deterministic results with only minor deviations in incremental costs and QALYs.

Figure 4. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis results—cost-effectiveness plane (dupilumab vs. baricitinib). Scatterplot of total costs and QALYS. Generated using 3,000 simulations of probabilistic sensitivity analysis. BSC, best supportive care; QALY, quality-adjusted life year.

Figure 5. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis results—cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (dupilumab vs. baricitinib). Generated using 3,000 simulations of probabilistic sensitivity analysis. BSC, best supportive care.

Table 6. Probabilistic base case results.

The cost-effectiveness results for each scenario analysis described in are reported in . The scenarios with the largest impact on the ICER of dupilumab versus baricitinib were the scenarios on model time horizon and the definition of treatment response.

Table 7. Scenario analyses results.

Discussion

This study estimated that, from the perspective of the Italian healthcare payer, treatment with baricitinib accrued fewer total costs but also slightly fewer total QALYs compared with dupilumab in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe AD who have experienced failure on, are intolerant to, or have contraindications to ciclosporin. The base case results suggested that, for the EASI75 response criteria, dupilumab was associated with 0.038 more QALYs and additional costs of €6,194 over a lifetime horizon than baricitinib, resulting in an ICER of €160,905/QALY. This ICER is significantly above the Italian payer willingness-to-pay threshold of €35,000/QALY,Citation27 suggesting that dupilumab cannot be considered cost-effective in comparison to baricitinib from the Italian healthcare payer perspective. Further explorations suggested that this conclusion was not altered substantially under the range of plausible uncertainty in input parameters.

A recent Italian consensus statement confirmed the inclusion of the itch Numeric Rating Scale in the definition of moderate to severe AD,Citation5 and in the ITC, baricitinib produced faster and numerically greater itch improvement at Week 16 than dupilumab in a population similar to our analysis population (patients with moderate to severe AD who had experienced failure on, were intolerant to, or had contraindications to ciclosporin).Citation28 In contrast, the EASI75 results at Week 16 numerically favored dupilumab. These findings suggest that, if itch is considered, the ICER for dupilumab versus baricitinib may be even greater than obtained in the current CEA.

This CEA had several strengths. These include that the Markov cohort model structure used for this analysis has been used previously in AD by users from academia and the pharmaceutical industry, as well as healthcare payers and decision makers,Citation7,Citation37,Citation50,Citation53 and results from this type of model have been widely published in the literature. All input cost and resource use data were aligned with the current Italian 2020 setting. The model was designed with functionality to include treatment sequencing should a new market entry occur. Thus, given the restrictions of that, tunnel states were implemented. The model also allows flexible induction input so that we could also change the response for itch at 4 weeks and use the same model structure. Additionally, where appropriate, sensitivity and/or scenario analyses were conducted to test assumptions around key inputs, in line with previously published economic models.Citation7,Citation26,Citation37 Notably, these analyses included large variations in discontinuation rate that did not change the overall cost-effectiveness conclusions.

Several limitations must also be mentioned. First, in the absence of lifetime data, several core assumptions were applied within the model to extrapolate available short-term clinical trial data. This extrapolation introduced a prominent source of uncertainty to this CEA, although long-term drug survival is difficult to estimate given the innovative nature of these treatments. Second, although important benefits of baricitinib treatment on sleep disturbance due to improvements in itch and skin pain have been observed in Phase 3 clinical trials,Citation19,Citation20 skin pain and sleep disturbance have not been assessed in dupilumab clinical trials and were, therefore, not included in the ITC used to inform this CEA. These benefits may not be fully captured by the EQ-5D, given that the EQ-5D does not include domains for itch and sleep. Furthermore, benefits in relation to itch and sleep may also extend further to other aspects of life such as social and sexual functioning.Citation7 In addition, baricitinib may provide added value to patients over and above that captured in this analysis; for example, oral administration (particularly in patients who cannot receive or fear injections). Third, discontinuation rates for baricitinib/BSC and dupilumab were derived from different sources and may therefore bias one treatment over another. Baricitinib/BSC discontinuation rates were derived from a Phase 3 clinical trial in adults with moderate to severe AD, the majority of whom had severe disease.Citation21 In contrast, dupilumab discontinuation rates were derived from a real-world study in which disease severity was not reported (72% had received prior systemic corticosteroids but only 10% had received prior cyclosporin).Citation31

Results of this CEA may not be generalizable to other populations. The analysis was based on data from a clinical trial and therefore has limitations compared with real-world populations; additionally, the analysis was conducted from an Italian healthcare payer perspective (including, for example, a target population reflective of the AIFA dupilumab population, age adjustments based on Italian life tables, treatment, AE, and resource costs derived from published Italian sources, and health state utilities based on an Italian value set) and therefore may not be generalizable to different countries. However, we expect that similar results would be seen in other countries where dupilumab is more costly than baricitinib.

Data supporting most treatments used for AD (including ciclosporin) are very limited. At the time of these analyses, dupilumab was the only drug currently reimbursed in Italy for the treatment of moderate to severe AD after cyclosporin failure, and baricitinib was the only reimbursed drug in this indication in other EU countries. Literature searches show that the two best evaluated drugs, with the strongest evidence for use in this indication, are baricitinib and dupilumab, although other drugs are being developed. For example, tralokinumab, upadacitinib, and abrocitinib are approved for the treatment of moderate to severe AD in Europe.Citation55–57 Thus, the options for this population have recently expanded, and the most suitable treatment options appear to be the JAK inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies against IL-4/IL-13 or IL-13. Relative cost-effectiveness may therefore be an important decision-making tool.

Conclusions

This CEA shows that dupilumab is more effective but also more costly from the Italian healthcare payer perspective compared with baricitinib in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe AD who have experienced failure on, are intolerant to, or have contraindication to ciclosporin. Based on ICERs determined in this patient population from the BREEZE-AD4 study, it is plausible to conclude that dupilumab cannot be considered cost-effective when compared with baricitinib in these patients. Given its oral administration, favorable risk/benefit profile and lower acquisition cost compared with dupilumab, baricitinib may offer a valuable, cost-effective treatment option, after failure on conventional systemic agents, for patients with moderate to severe AD in Italy.

Transparency

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Erin Johansson, Maurizio Mezzetti, Na Lu and Silvia Sabatino are full-time employees and may hold shares in Eli Lilly and Company. Massimo Giovannitti was a full-time employee of Eli Lilly and Company during the conception and development of the work.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (63.5 KB)Acknowledgements

None stated.

Reviewer disclosure statements

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- National Health Service. Symptoms: atopic eczema. 2019 Dec 5 [Internet]; [cited 2022 Nov 22]. Available at https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/atopic-eczema/symptoms/.

- Katoh N, Ohya Y, Ikeda M, et al. Committee for Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Atopic Dermatitis 2018, the Japanese Society of Allergology, the Japanese Dermatology Association. Japanese guidelines for atopic dermatitis 2020. Allergol Int. 2020;69(3):356–369. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2020.02.006.

- Langan SM, Irvine AD, Weidinger S. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2020;396(10247):345–360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31286-1.

- Karimkhani C, Dellavalle RP, Coffeng LE, et al. Global skin disease morbidity and mortality: an update from the global burden of disease study 2013. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(5):406–412. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.5538.

- Costanzo A, Amerio P, Asero R, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe adult atopic dermatitis: a consensus by the Italian Society of Dermatology and Venereology (SIDeMaST), the Association of Italian Territorial and Hospital Allergists and Immunologists (AAIITO), the Italian Association of Hospital Dermatologists (ADOI), the Italian Society of Allergological, Environmental and Occupational Dermatology (SIDAPA), and the Italian Society of Allergy, Asthma and Clinical Immunology (SIAAIC). Ital J Dermatol Venerol. 2022;157(1):1–12. doi: 10.23736/S2784-8671.21.07129-2.

- Wei W, Ghorayeb E, Andria M, et al. A real-world study evaluating adeQUacy of Existing Systemic Treatments for patients with moderate-to-severe Atopic Dermatitis (QUEST-AD): baseline treatment patterns and unmet needs assessment. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123(4):381–388.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.07.008.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Single technology appraisal. Dupilumab for treating moderate to severe atopic dermatitis after topical treatments [ID1048] [Internet]; [cited 2022 Nov 22]. Committee Papers. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta534/documents/committee-papers. Accessed 22 November 2022.

- Sciattella P, Pellacani G, Pigatto PD, et al. The burden of atopic dermatitis in adults in Italy. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2020;155(1):19–23. doi: 10.23736/S0392-0488.19.06430-7.

- Zimmermann M, Rind D, Chapman R, et al. Economic evaluation of dupilumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a cost-utility analysis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17(7):750–756.

- Wollenberg A, Kinberger M, Arents B, et al. European guideline (EuroGuiDerm) on atopic eczema – part II: non-systemic treatments and treatment recommendations for special AE patient populations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(11):1904–1926. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18429.

- Wollenberg A, Kinberger M, Arents B, et al. European guideline (EuroGuiDerm) on atopic eczema: part I – systemic therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(9):1409–1431. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18345.

- European Medicines Agency. Dupixent: authorisation details. 2017 Sep 26 [Last update: 2021 Jan 22; cited 2022 Nov 22]. Available at https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/dupixent#authorisation-details-section.

- European Medicines Agency. Protopic: authorisation Details. 2002 Feb 27 [Last update: 2020 Sep 7; cited 2022 Nov 22]. Available at https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/protopic#authorisation-details-section.

- Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(24):2335–2348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610020.

- Aldredge LM, Young MS. Providing guidance for patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis who are candidates for biologic therapy: role of the nurse practitioner and physician assistant. J Dermatol Nurses Assoc. 2016;8(1):14–26. doi: 10.1097/JDN.0000000000000185.

- Ariëns LFM, van der Schaft J, Bakker DS, et al. Dupilumab is very effective in a large cohort of difficult-to-treat adult atopic dermatitis patients: first clinical and biomarker results from the BioDay registry. Allergy. 2020;75(1):116–126. doi: 10.1111/all.14080.

- European Medicines Agency. Olumiant: authorisation Details. 2017 Feb 13 [Last update: 2020 Dec 15; cited 2022 Nov 22]. Available at https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/olumiant#authorisation-details-section.

- Fridman JS, Scherle PA, Collins R, et al. Selective inhibition of JAK1 and JAK2 is efficacious in rodent models of arthritis: preclinical characterization of INCB028050. J Immunol. 2010;184(9):5298–5307. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902819.

- Simpson EL, Lacour J-P, Spelman L, et al. Baricitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis and inadequate response to topical corticosteroids: results from two randomized monotherapy phase III trials. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(2):242–255. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18898.

- Reich K, Kabashima K, Peris K, et al. Efficacy and safety of baricitinib combined with topical corticosteroids for treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(12):1333–1343. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.3260.

- Bieber T, Reich K, Paul C, et al. Efficacy and safety of baricitinib in combination with topical corticosteroids in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with inadequate response, intolerance, or contraindication to cyclosporine: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase iii clinical trial (BREEZE-AD4). Br J Dermatol. 2022;187(3):338–352. doi: 10.1111/bjd.21630.

- Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA). DUPIXENT (dupilumab) dermatite atopica (AD). 2022. [Internet]; [cited 2022 Nov 22]. Available at https://www.aifa.gov.it/documents/20142/1663139/Scheda_Registro_DUPIXENT_08.03.2022.zip.

- Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA). Guidelines for the compilation of the dossier to support the reimbursability and price application of a medicine. Version 1, 2020. [Internet]; [cited 2022 Nov 22] Available at https://www.aifa.gov.it/documents/20142/1283800/Linee_guida_dossier_domanda_rimborsabilita.pdf.

- Eli Lilly and Company Limited. Olumiant (baricitinib) 4 mg film-coated tablets. Summary of product characteristics. [Internet]; [cited 2022 Nov 22] Available at https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/7486/smpc#.

- Sanofi Genzyme. Dupixent (dupilumab) 300 mg solution for injection in pre-filled pen. Summary of product characteristics. [Internet]; [cited 2022 Nov 22]. Available at https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/11321/smpc.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Dupilumab for treating moderate to severe atopic dermatitis after topical treatments. Technology appraisal guidance [TA534]. 1 August 2018. [Internet]; [cited 2022 Nov 22]. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta534.

- Papadia DG, FARMACOECONOMIA e FARMACOEPIDEMIOLOGIA. Università degli Studi di Trieste – Corsi di Studio in Farmacia Per gli studenti del Corso di Laurea in Farmacia ed in C.T.F. – versione aggiornata marzo 2018. [Internet]; [cited 2022 Nov 22]. Available at https://moodle2.units.it/pluginfile.php/194171/mod_resource/content/1/farmeconepid.pdf. [Italian]

- de Bruin-Weller MS, Serra-Baldrich E, Barbarot S, et al. Indirect treatment comparison of baricitinib versus dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12(6):1481–1491. doi: 10.1007/s13555-022-00734-w.

- Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE, et al. The results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(6):683–691. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00049-8.

- de Bruin-Weller M, Thaçi D, Smith CH, et al. Dupilumab with concomitant tropical corticosteroid treatment in adults with atopic dermatitis with an inadequate response to intolerance to ciclosporin a or when this treatment is medically inadvisable: a placebo-controlled, randomized phase III clinical trial (LIBERTY AD CAFÉ). Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(5):1083–1101. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16156.

- Silverberg JI, Guttman-Yassky E, Gadkari A, et al. Real-world persistence with dupilumab among adults with atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126(1):40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.07.026.

- Zuberbier T, Orlow SJ, Paller AS, et al. Patient perspectives on the management of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118(1):226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.02.031.

- I.Stat. Life tables. 2019. [Internet]; [cited 2022 Nov 22]. Available at http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=DCIS_MORTALITA1#.

- van Hout B, Janssen MF, Feng YS, et al. Interim scoring for the EQ-5D-5L: mapping the EQ-5D-5L to EQ-5D-3L value sets. Value Health. 2012;15(5):708–715. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.02.008.

- Scalone L, Cortesi PA, Ciampichini R, et al. Italian population-based values of EQ-5D health states. Value Health. 2013;16(5):814–822. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.04.008.

- Ara R, Brazier JE. Using health state utility values from the general population to approximate baselines in decision analytic models when condition-specific data are not available. Value Health. 2011;14(4):539–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2010.10.029.

- Kuznik A, Bégo-Le-Bagousse G, Eckert L, et al. Economic evaluation of dupilumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adults. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7(4):493–505. doi: 10.1007/s13555-017-0201-6.

- Compendio Farmadati. 2020. [Internet]; [cited 2022 Nov 22]. Available at https://www.farmadati.it/. [Italian]

- Information Hospital Service. 2021. [Internet]; [cited 2022 Nov 22]. Available at https://www.infohospital.com/en/index.html.

- Gelmetti C, Girolomoni G, Patrizi A. revisione critica di linee guida e raccomandazioni pratiche per la gestione dei pazienti con dermatite atopica. [Internet]; [cited 2022 Nov 19]. Available at https://www.pacinimedicina.it/wp-content/uploads/dermatite-atopica_sidemast.pdf. [Italian]

- Gazzetta Ufficiale. 2013. 23. [Italian]

- Garattini L, Castelnuovo E, Lanzeni D, et al. Durata e costo delle visite in medicina generale: il progretto DYSCO. FE. 2003;4(2):109–114. [Italian] doi: 10.7175/fe.v4i2.773.

- Ministry of Health. Pronto Soccorso e sistema 118 - Proposta metodologica per la valutazione dei costi dell’emergenza. 2021. [Italian]

- Nomenclatore Tariffario FASDAC. 2020.

- Sistema Socio Sanitario. Regione Lombardia ASST Spedali Civili. Psicologia. 2022. [Internet]; [cited 2022 Dec 8]. Available at https://www.asst-spedalicivili.it/servizi/Menu/dinamica.aspx?idSezione=616&idArea=38147&idCat=40274&ID=45520&TipoElemento=categoria. [Italian]

- Palmonella A. Gli psicologi penitenziari chiedono aiuto all’ordine degli psicologi. [Internet]; [cited 2022 Dec 8]. Available at https://www.altrapsicologia.it/articoli/gli-psicologi-penitenziari-chiedono-aiuto-allordine-degli-psicologi-2/?print=print. [Italian]

- Tariffario FISDAF. 2016. [Italian]

- Tariffario regionale per la remunerazione delle prestazioni di assistenza ospedaliera. 2017. [Internet]; [cited 2022 Dec 8]. Available at https://www.regione.sardegna.it/documenti/1_26_20171122122049.pdf. [Italian]

- Decreto Commissario ad acta U00310/13. Approvazione del tariffario regionale per la remunerazione delle prestazioni di assistenza ospedaliera D.M.18.10.12. [Internet]; [cited 2022 Nov 22]. Available at https://www.asl.vt.it/Staff/SistemiInformativi/Documentazione/sio/pdf/Decr_U00310_04_07_2013.pdf. [Italian]

- Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER). Dupilumab and crisaborole for atopic dermatitis: effectiveness and value final evidence report and meeting summary. 8 June 2017. [Internet]; [cited 2022 Nov 22]. Available at https://icer.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/MWCEPAC_ATOPIC_FINAL_EVIDENCE_REPORT_060717.pdf.

- Silverberg JI, Simpson EL, Wollenberg A, et al. Long-term efficacy of baricitinib in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis who were treatment responders or partial responders: an extension study of 2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(6):691–699. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.1273.

- Deleuran M, Thaçi D, Beck LA, et al. Dupilumab shows long-term safety and efficacy in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis enrolled in a phase 3 open-label extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(2):377–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.074.

- Woolacott N, Hawkins N, Mason A, et al. Etanercept and efalizumab for the treatment of psoriasis: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 2006;10(46):1–233. i-iv. doi: 10.3310/hta10460.

- Peserico A, Städtler G, Sebastian M, et al. Reduction of relapses of atopic dermatitis with methylprednisolone aceponate cream twice weekly in addition to maintenance treatment with emollient: a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, controlled study. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158(4):801–807. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08436.x.

- European Medicines Agency. Adtralza (tralokinumab): authorisation details. 2021 Jun 17. [Internet]; [cited 2022 Nov 22]. Available at https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/adtralza#authorisation-details-section.

- European Medicines Agency. Cibinqo (abrocitinib): authorisation details. 2022 Oct 11. [Internet]; [cited 2022 Nov 22]. Available at https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/cibinqo#authorisation-details-section.

- European Medicines Agency. Rinvoq (upadacitinib): authorisation details. 2022 Sep 22. [Internet]; [cited 2022 Nov 22]. Available at https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/rinvoq#authorisation-details-section.