Abstract

As the Great Power which initially authorized the Zionist settler-colonial project in historic Palestine, Britain has played a decisive role in the one hundred-year war against Palestinians. This essay analyses moments of encounter between Palestinians and British human rights activists, which is to say between those who relegate British imperial history to a definitive past and those who continue to live with the resilient structures of the British imperial past and the ongoing settler-colonial present. Paying attention to these moments of encounter is shown to offer a way of understanding Palestinian experiences of the past as an “ever-living present”. Furthermore, in what I call these “Balfour conversations”, when British subjects were being asked to apologize for Britain’s historic actions, I suggest that something akin to the Althusserian “hail” is at work. Through its attempt to understand the processes by which interpellation functions in this context, this essay explores how implication is frequently unacknowledged or denied through reactions of defensiveness, shock, and anger – responses which are also shown to be illustrative of collective “imperial dispositions”. Throughout the essay, I unpick how it is that British activists are structurally implicated, and something of what lies beneath these imperial dispositions, in order that different ways of acting within transnational solidarity relationships might be imagined possible.

History in an active voice is only partly about the past. … It requires assessing the resilient forms in which the material and psychic structures of colonial relations remain both vividly tactile to some in the present and, to others, events too easily relegated to the definitive past. (Stoler Citation2016, 169)

Introduction

One Friday evening during a research trip to Israel and Palestine I was at the Jerusalem hotel to interview Clare about her three months volunteering as a human rights monitor in the occupied Palestinian territories (oPt). The hotel is a popular destination for international NGO workers looking for an after-work beer in the pleasant atmosphere of this Ottoman-era building with its sandy-coloured stonework and courtyard bar area. The hotel has, I learned, an interesting history: originally built as an Ottoman police station, it later became a registration centre for Palestinian draftees to the Ottoman army fighting British forces during the First World War. Situated near the road marking the seam between Palestinian East Jerusalem and Israeli-governed West Jerusalem, the hotel has also borne witness to successive waves of occupation – from the city’s capture by British forces in 1917, to the 1948 Jordanian occupation of East Jerusalem and the Old City, to the Israeli annexation of East Jerusalem in 1967. Yet, life under occupation is by no means part of Jerusalem’s “definitive past”; instead it is an ongoing reality for Palestinians living in East Jerusalem. For example, the hotel is also a ten-minute walk away from Sheik Jarrah, the site of long-running protests against the ongoing forced evictions of dozens of Palestinians from their homes by Israeli settlers.

Towards the end of meeting with Clare that evening, I asked her whether she thought British volunteers like herself had a particular responsibility to help Palestinians because of Britain’s history of imperial involvement in the region. She took a lengthy, somewhat uncharacteristic pause before saying:

I think people [Palestinians] are more conscious of the history here than we are. … I mean maybe there are people [non-Palestinians] thinking the Nakba was 1948 – get over it – but that is not how it is seen here. You know, they think in historical terms, and so must we. It is almost as if, you know, Balfour, I had barely heard of him until I got a bit involved – but most people [in the UK] will never have heard of him, but here, they know their stuff.

In many, although not all of these conversations, Balfour’s name was mentioned and often British volunteers were asked to apologize for the 1917 Balfour Declaration. I refer to these encounters as “Balfour conversations” since Balfour’s name appeared to act as a signifier, pointing to all that might be considered the afterlife of the British Mandate in the oPt. In addition to these ethnographic findings, Palestinian scholarship also points to the ongoing significance of Britain’s historic role in the Palestinian present. Foundational to my argument is Rashid Khalidi’s formulation that the “unceasing colonisation” (Citation2020, 7) of Palestine can be seen as a one hundred years’ war against Palestinians which began with the issue of the Balfour Declaration and its promise of a national home for Jews in Palestine. The Balfour Declaration, as Rana Barakat argues, was a merging of “Great Britain’s colonial aspirations in Palestine with the Zionist movement’s settler colonial designs” (Citation2021, 92). In regard to the Palestinian Arabs already resident in Palestine, the declaration made no specific mention of the name of the Palestinian peoples nor of their political rights; it merely stated that “nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of the existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine”. Scholars like Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian argue that the Declaration thus constitutes the “most well-known example of the eviction of Palestinians from humanity” (Citation2014, 278). And whilst it is primarily the events of 1948 that have become the “the reference point for all other events in the Palestinian narrative”, Yara Hawari points out that the Balfour Declaration is commonly viewed as a “documented and written prelude to the Nakba” (Citation2018, 167). The Nakba (meaning catastrophe in English) refers to events of 1947–48, the final years of the British Mandate, when more than 78 per cent of historic Palestine was taken by Zionist forces, 530 Palestinian towns and villages were destroyed, 750,000 Palestinians were made refugees and the State of Israel was established. The year 1948 far from marked the completion of the Zionist settler-colonial project, however. The “ongoing Nakba” is the term used to describe the “continuing state of displacement, exclusion, rightlessness, and insecurity” (Sayigh Citation2015, 2) in which Palestinians continue to live, both within and without the oPt.

Exploring the idea that British citizens are implicated subjects (Rothberg Citation2019), in this essay I demonstrate the similarities between the “Balfour conversations” and the Althusserian “hail” which interpellates the subject into being. However, before beginning an analysis of the Balfour conversations, the idea of British implication will be set out in more detail. To provide illustration of some of the ways in which particular subjects are implicated, the first section will also detour into some reflections on my own positionality as a white British scholar-activist-traveller to the oPt, reflections which were elicited by the discovery of this 1926 tourist map. Second, paying attention to the Palestinian call will be shown to offer a way of understanding the “synchronicity of the colonial and the post-colonial” in Palestine (Massad Citation2006, 14). The third and fourth sections open up an inquiry into the ways in which the British subject reacts to the Palestinian message, focusing particularly on reactions of defensiveness, shock and anger. The examples used demonstrate that sometimes the British activist puts up barriers to responding to the call and accepting implication, trying instead to preserve the idea of themselves as superior and innocent. Judith Butler’s (Citation1997) reading of Althusser is used here to further understand the different ways in which implication is reckoned with. My intention is not to depoliticize the issue by focusing on the affective responses of individuals. I am much less interested in passing judgement on individual attitudes than I am in thinking about the way their reactions are illustrative of collective dispositions which “circumscribe what one can know” and thus limit the extent to which individuals recognize themselves as implicated. Stoler writes that imperial dispositions are “acts of ignoring rather than ignorance” but also “ways of living in and responding to, ways of being and seeing oneself” (Citation2009, 255). This means individuals bear responsibility for their acts but, as ways of being, dispositions are also rooted in structures of thought which exceed the individual and can be seen as a legacy of centuries of liberal and imperial philosophy, culture, economics, and politics in Britain. In this essay, I seek to unpick something of what lies beneath these dispositions in order that different ways of acting within transnational solidarity relationships might be imagined possible.

The implicated British subject

While British citizens born long after the events of 1917 and 1948 cannot be held directly responsible for Britain’s historic actions, I argue that they are implicated in settler-colonial violence in Palestine in a particular way because of Britain’s historic and contemporary complicity with Zionist settler-colonialism. Using Khalidi’s framing of the past one hundred (plus) years as a war against Palestinians, it is clear Britain was but one player among many that waged, and continue to wage this war. The Balfour Declaration promised “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people” and was signed off by the British government of the time. However, it only came into force in 1923 when it was included with the Covenant of the League of Nations and the British Mandate for Palestine became official. Britain was thus not entirely independent in its actions.Footnote2 It was accountable to the international community for its delivery of the Mandate, and it did not have full control over the Zionist settler-colonial movement, which was “beholden to Britain” but also independent of it (Khalidi Citation2020, 52). Yet, while Britain was not acting alone, and while the British role in Israel and Palestine has definitely changed since 1948, its actions – both historic and ongoing – remain significant. British subjects remain entangled in such histories since, as Tessa Morris-Suzuki says, “we live within the structures, institutions, and webs of ideas that the past has created” (Citation2004, 235). This entanglement creates what Michael Rothberg has called the implicated subject – a “participant in histories and social formations that generate the positions of victims and perpetrator” (Citation2019, 1). While subjects are often entirely unconscious of their participation in such regimes of dominance, however unwittingly, they enable the “destabilising intrusion of irrevocable pasts into an unredeemed present” (9). Reckoning with implication, on the other hand, is the place where hierarchies and histories of power can be acknowledged rather than repressed (200).

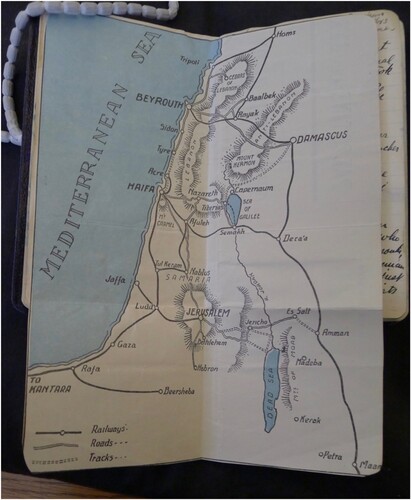

Whilst researching British Quaker missions work in Mandatory Palestine, I came across the travel diaries of Margret Emmott, a British woman who travelled to Syria and Palestine to visit various missionaries in the Quaker community (Margret Emmott papers, Citation1926–Citation1927). Neatly folded up to fit within the pages of the diary was a map which looked like it had been cut out of a larger tourist leaflet (See ).

At a first glance, the map made the region appear attractively uncomplicated and devoid of violence. Drawn for English-speaking travellers in the 1920s, the map obviously showed no evidence of the present regimes of immobility or incarceration, no mark of an impassable border between Lebanon and Israel like there is today; no green line or apartheid wall marking off the occupied Palestinian territories from Israel; no barriers to mark the space inhabitants of Gaza are trapped in, no sign of the lines in the sea marking the point up to which Gazan fishing boats are permitted to travel. In fact, the only borders shown were ones which demarcated the land from the sea.

On further reflection, however, it was clear that this Mandate-era mapping was not innocent at all. This map’s erasure of complexity narrated space not only from the vantage point of pre-state Israel, but also from that of the colonizer rather than the colonized. Yet, it had taken some moments before I shook myself into realizing this – until then I had simply stared unthinkingly at the map, indulging in utopian dreams of simple geopolitics in the region. According to her diaries, Margret’s travels took her right across both present-day Lebanon and Palestine as she visited the various Quaker mission schools and orphanages and other tourist destinations. For Margret, the map narrated, in a colonial tongue, a reality in which she need be less concerned with land ownership and sovereignty, but rather how she could enter and traverse the land mass. The 1926 mapping highlighted some of the material realities: roads and railway tracks that beckoned the privileged European traveller to avail themselves of the imperial infrastructure that could, in a matter of hours, sweep them from the coast inland, towards and in between tourist and religious attractions, from Beirut to Haifa or from Jerusalem to Gaza. In her summary of some of the scholarship which followed Said’s Orientalism and explored the links between travel and power, Rebecca Stein says we can now understand “travel narratives as instruments of colonial conquest, discursive tools intimately related to the more violent projects of resource extraction, settlement, and colonial governance” (Citation2008, 12). Maps are also discursive artefacts, techniques of power at the service of capitalism and imperialism, structures within which the Quaker Margret Emmott, a white, English-speaking, middle-class British woman, not so different to me, also lived. With its lack of borders and its English language naming of towns and cities, I realized that what had appeared at first on the map as simplicity was actually part of a gendered imperial and Orientalist discourse which portrayed the colonies as spaces available for the curious Western traveller to “know”, “penetrate”, “extract from” and colonize with ease (Yeğenoğlu Citation1998; Ahmed Citation2006; Said Citation1979).

Stein’s study demonstrates how contemporary Israeli tourism and travel itineraries in the Oslo period are situated within older histories of both mobility and spatial incarceration in the region. She contends that “Israeli tourist and leisure practices have been historically enabled by the journeys of soldiers, immigrants, and refugees” (Citation2008, 14). Analogously, I thought about how the British scholar undertaking research in the oPt takes paths already trod by colonial agents who travelled to extract knowledge from colonized spaces (Daswani Citation2021). This idea, that the travel practices of privileged tourists, scholars or activists are “historically enabled” by prior imperial histories in the region, finds resonance with Ahmed’s (Citation2006) work which thinks about how racialized bodies move through space. Whiteness, she argues, is a racialized positioning shaped by colonial histories, and affects the way subjects are oriented towards the places where the racialized Other dwells. To a white imperial subject it appears as if everywhere is “open access”, since.

what is reachable is determined precisely by orientations that have already been taken and that have been repeated over time. … Acts of domestication are not private; they involve the shaping of collective bodies, which allows some objects and not others to be within reach. (Ahmed Citation2006, 117)

A Palestinian perspective: the Balfour conversations

Sami is a Palestinian who works with the international human rights organization which Clare and the other volunteers participated in. He talked to me about what happens when volunteers visit Palestinian villages to gather testimonies of human rights violations:

… if you are coming for a visit to know about what happened yesterday, I won’t just give you the short information, I will let you know all the history … for like ten to fifteen minutes – and then answer your questions for what happened yesterday … they will give you the history of the place – the village, the community and talk about their ownership properties and their great-grandfathers who were living in this community and now are still living here – and then they will tell them [the volunteers] the story.

Writing of visits to Palestine, Adania Shibli describes being subjected to hours of interrogations and searches when coming through Israeli border control. What she notes about one such experience was that her watch stopped working during this time. It went “into a coma, unable to count time” (Citation2012, 67), she writes, suggesting that “maybe it simply refuses to count the time that is seized from my life, time whose only purpose is to humiliate me and drive me to despair” (68). As well as the point she is making about the way her watch became her ally in these instances, “trying to comfort me by making me believe that all that searching and delay had lasted zero minutes”, her prose also suggests that, in refusing to count the theft of hours and minutes, days and years that the colonizing powers take from the colonized, the watch also performs an act of refusal. For it makes no sense to attempt to count time in a linear fashion when settler-colonial violence continues and “the past remains present in an ongoing Nakba” (Barakat Citation2021, 92). As Nayrouz Abu Hatoum (Citation2021) argues, the Palestinian sense of temporality is much more cyclical than linear. It is from within this experience of the past as an “ever-living present” (Khoury Citation2022, 56) that Sami also described how Palestinians “see” the past, and then asked British subjects to join them in this way of “seeing”.

Well, in a few communities it is still [pause] in some interviews when the host or the local person asks the [volunteers] where they are from and there is a person from the UK – before starting the conversation he asks them – “you have to say sorry for what Balfour did”. So, this is something for us as locals we won’t ever forget. It’s not Balfour alone – so I am not blaming Balfour alone – no – or I am not blaming the people from the UK for what Balfour did, but yes, in some communities they still remember. … And especially if there is a Nakba witness, if we are talking to a Nakba witness he will mention Balfour.

One British volunteer, Sarah, wrote to me recalling the following incident which had occurred some years ago, at the time when Tony Blair was British prime minister. Sarah and her colleagues were monitoring an Israeli checkpoint which regulated Palestinian farmers’ access to land they owned, but which was caught on the “wrong” side of the Israeli apartheid wall. The encounter was meaningful to Sarah, so much so that she specifically thanked me for asking about it when she wrote:

The three of us were monitoring the military checkpoint which separated the farmers from their land. Early in the morning they [Palestinians] came down the dusty track from the village and were put through the humiliation of checks of IDs, permits, searches – and sometimes being turned back. On this morning a venerable couple came down on a mule-cart. As he drew level with us, the old man and ourselves exchanged morning greetings. But after the courtesies, he paused and in a sweeping gesture took in the checkpoint, the barbed wire fence, the Israeli soldiers and their jeeps, he looked at us, and said simply: “Bush! Blair! Balfour!” Then he cracked the whip and drove on. That was hardly a conversation, but it said everything. At the time I felt shocked, because of the barely contained anger in those three words. Balfour was in the past. Bush and Blair were politicians in the present. And although we had just enough Arabic to exchange polite greetings – we were part of their world.

This encounter, painted here so vividly, bears a likeness to a well-known but imaginary one conjured up by Louis Althusser (Citation1984) and used to explain the way ideology transforms individuals into subjects. In Althusser’s scene a policeman hails the individual on the street with a “hey you!”; in Sarah’s story there is a Palestinian in a mule cart passing through an Israeli checkpoint, calling out “Bush, Blair, Balfour!” Whilst Palestinians cannot be likened to authority figures issuing the call of hegemony, there are helpful similarities found in the patterning of the call, turn, response and “become”.Footnote3 In both cases, an individual turns around at the sound of someone addressing them, recognizes that the call was hailing them specifically, responds to that call in a turning around, and simultaneously self-identifies with, or “becomes” that which the interpellator addressed them as. In Sarah’s account the Palestinian’s three words, along with his pause, his look, and his gestures, constitute a hailing: a call to the individual to turn around and realize that they are part of a lineage which stretches from Bush and Blair to Balfour. This lineage marks the Palestinian experience of the continuity between past and present violence; it is the present Palestinian experience of continuity between Balfour (as a representative of European colonial powers) and Bush and Blair (representatives of contemporary imperial powers) that renders the call especially urgent. In opposition to what one participant told me when he felt he was being “blamed for what happened in the past”, I do not consider these requests for an apology as merely an inability to forget what lies finished in the past. As the Palestinian scholar Elias Khoury says, not everyone has the luxury of being able to choose between remembering or forgetting the past. “Like all human beings, we too want to forget”, he writes. “A person can forget the past, but try as she might, she cannot forget the present. At the hands of the Israelis, our past has become an ever-living present that does not pass, so how are we to forget?” (Citation2022, 56). Although I reference these conversations as the Balfour conversations implying they are concerned with something historic, we can see from this man’s call that Britain’s complicity with violence against Palestinians cannot be relegated to a sealed-off past. The naming of the continuity between Bush, Blair, Balfour is that which collapses the passing of time between Balfour and Blair, and demonstrates British implication in a regime of domination and colonialism which has not yet ended.

Grappling with implication (1): a defensive reaction

Althusser argued that “ideology has always-already interpellated individuals as subject” (Citation1984, 49). So, drawing on this, I suggest that there is both the fact of implication and, at the same time, a process of being interpellated into a conscious understanding of implication. As I read various iterations of Sarah’s encounter in accounts written by former British human rights monitors who had had similar experiences, I saw that sometimes these conversations impacted on volunteers significantly, and that there was something of what Avtah Brah called the “electric moment[s]” (Citation2012, 9) of interpellation in them. At the same time, three of the accounts also surprised me by containing remarkably similar lines of defence against interpellation. Tom wrote about a conversation he had had while out shopping in the town where his team were staying. The Palestinian he had met.

told me that the UK has the principal responsibility, through the Balfour Declaration, for the suffering and current situation of Palestinians, and suggested that my presence in the … programme was hypocritical and prompted by a desire to clear my conscience. My first reaction was defensive, but it quickly brought me to a realisation that his anger was understandable and that I was not in a position to challenge his accusation. It upset me because despite the oversimplification of his accusation I felt its fundamental justice. It also struck a nerve with regard to my own motivation.

he responded to me specifically about how the situation in Palestine was the fault of the British. I followed up by speaking about the Balfour Declaration but that it … also was intended to protect the rights of people living in Palestine. … I felt frustrated and ignored by the dismissal of what I said, which was in response to a comment framed in a passively hostile (and what I found to be rude) manner. As the placement continued, we had a great deal to do with the contact I refer to. We assisted him … on a frequent basis. So, it didn’t matter, and I “placed” his comments alongside our other key contacts whose analysis was more sophisticated and nuanced.

For many, the whole complex history of the last 140 years in Palestine had been reduced to the argument that the British had let “the Jews” in and the whole subsequent mess was their fault. I felt a number of different things: understanding why they felt as they did; acceptance that British power in its imperial and post-imperial phases had/has often been used arrogantly and wrongly; a little irritation that a somewhat simplistic version of the actual history was being conveyed, which couldn’t easily be corrected without offence.

Gada Mahrouse argues that the Universal subject believes he is “without history”, “in so far as it can step out of historical events such as colonialism and slavery” (Citation2014, 143). In his imagined freedom from the confines of historical legacies there is an assumption that the volunteer subject is more able to fully “know” history because they are detached from it, positioned as outside the Palestinian experience. This imagined disembodied positioning, reminiscent of Haraway’s (Citation1988) view from nowhere, is in direct contrast to Sarah’s realization that “we were part of their [the Palestinians’] world”. Yet, in Gavin, Eric and Tom’s accounts, the logics of liberal Universalism enable them to dismiss knowledge produced by Palestinians who are Othered as more entangled in the particularities of their situation, and thought of as producing simplistic versions of history. Even if colonial histories are “too easily relegated to the definitive past” (Stoler Citation2016, 169) by the colonizer, no one can step out of historical events. The colonized do not live a more particular, embodied life than the colonizer despite the uneven distribution of pain and injustice which “adheres to some bodies compelled to remember” (67). When volunteers dismiss Palestinian knowledge of the situation, the British subjects’ own particular positioning in colonial history is obscured, and this constructs a false division between different types of subjects who have different ways of knowing. British subjects become falsely associated with a detached, objective knowledge and the Palestinian knowledge is Othered, feminized in its association with lived experience and a lack of objectivity. The Palestinian call to implication is thus more easily ignored.

Grappling with implication (2): on not being welcomed

One account of a Balfour conversation stood out as being different to the others. It recounts an incident where a British volunteer was told he was not welcome in a certain West Bank village because of his nationality. This was not an experience peculiar to just one volunteer – I had heard similar accounts about this village from several other Brits and Palestinian staff members. In Philip’s account of the experience he says that one particular village.

barred me from visiting them. The others [in his multinational team] were allowed to go but, because I was British, I was not allowed to join them. The explanation given was that the Balfour Declaration was a major factor in bringing about the creation of the state of Israel, the British people were therefore significantly responsible for the situation that exists today, they wanted no British [volunteers] in their village. Obviously, it was right to abide by this and so I stepped back from the visit. I was really shocked though. I thought they would welcome a Brit like me who recognised the reality of the situation, how the occupation affects their lives, wanting to show my support by working as a [human rights monitor]. I have to admit that their refusal to meet me actually left me feeling quite angry. I thought, here I am facing up to Israeli soldiers and settlers on an almost daily basis, feeling quite threatened sometimes and yet the usually high level of Palestinian hospitality was not being extended to me. It didn’t make sense to me, but I had to accept it of course.

As Althusser himself insists, this performative effort of naming can only attempt to bring its addressee into being: there is always the risk of a certain misrecognition. If one misrecognizes that effort to produce the subject, the production itself falters. The one who is hailed may fail to hear, misread the call, turn the other way, answer to another name, insist on not being addressed in that way. (Butler Citation1997, 95)

However, in the other volunteers’ accounts, while feelings of guilt are not necessarily dwelt upon, there is less resistance to the call. In Tom’s account analysed above, we read that the Palestinian accused him of volunteering in order to clear his conscience, which was an accusation that “struck a nerve”. Tom’s metaphorical use of language positions the impact of the interpellation as a bodily sensation. It conveys the idea that the hailing lands in the body in a way akin to a strike to the nervous system: it shakes, disorientates, surprises the subject who is not used to being the object of Palestinian anger and, above all, is not accustomed to the idea of being an imperial subject. This is related, I think, to the feelings of shock which were articulated in Philip’s account and by other volunteers. Clare, for example, mentioned shock twice. She wrote, “I felt shocked but also defensive, not of the British action but the suggestion that I should account for the actions of the British Government”. Sarah also mentioned it in reaction to the “Bush, Blair, Balfour” greeting, saying shock was a result of realizing there was “barely contained” anger in the Palestinian’s words.

Feelings of shock are, I would argue, the result of the volunteers meeting with both the expected and the unexpected in the Palestinian call. Whilst some Palestinians expressed gratitude for their solidarity and help, in these encounters Palestinians surprise the volunteers by refusing them entry to their homes, by demanding an apology or by accusing them of selfish motives for coming to Palestine. This was not expected. Yet, returning to the phrase used by Tom, it “struck a nerve”, the accusation sometimes felt like a blow to a sensitive area, an area perhaps already weakened by a previous encounter. Here, then, the hailing has the capacity to touch a place which the subject has some familiarity with. This speaks to Butler’s critique when she connects the process of interpellation with the subject’s conscience, saying that the decision to turn and self-identify with the hail must be the result of an interior readiness which pre-exists the moment of interpellation. “Although there would be no turning around without first having been hailed, neither would there be a turning around without some readiness to turn” (Citation1997, 107). In Tom’s case, the interpellation “strikes” this place of readiness, so that he both defends himself against the accusation and says he felt the “fundamental justice” of the Palestinian’s anger. Shock therefore acts ambivalently: it both closes the subject down, allowing them to re-entrench themselves as unimplicated, or/and it has the potential to open the subject up. Eric, also cited above, wrote that he had been “pulled up to think about the effect of Balfour. … To use the current phrase, it made me ‘check my privilege’”. And Sarah talked about how when she gave advocacy presentations in the UK, she always included the story of her encounter with the Palestinian farmer at the checkpoint. She said that the experience had led her to help organize a Citizen’s Apology for the Balfour Declaration in Scotland.

Conclusion

As Ruba Salih writes, narratives are themselves “processes of subjectification, they are ways in which women and men become subjects and live their lives as a story within a history” (Citation2017, 747). I would argue that it is a politically and ethically urgent task to investigate the narratives in which one lives, and that reckoning with implication is a necessary precursor to building more ethical transnational solidarity relationships across difference (Rothberg Citation2019). However, examining a call to implication through the lens of interpellation offers the opportunity to examine some of the “forms of psychic and social denial” (Citation2019, 8) of implication which arise from British human rights monitors’ encounters with Palestinians on Palestinian land. It is clear from what has been analysed that interpellation often fails; volunteers do not always seem to recognize themselves in this call, and fail to become aware of their implication. Which begs a question that Butler has already articulated: “Why should I turn around? Why should I accept the terms by which I am hailed?” (Citation1997, 108). Why should British subjects be attentive to the Palestinian call to recognize their implication? In Butler’s response to her own question, she discusses the need for a readiness to turn to face the law which is represented by the police officer in Althusser’s scene. She says it “means that, prior to any possibility of a critical understanding of the law, there is an openness or vulnerability to the law, exemplified in the turn toward the law” (Citation1997, 108). The need for openness, for a readiness to turn, also fits with Rothberg’s statement that to confront implication is to adopt an open, vulnerable posture towards oneself and others. Reckoning with implication is not about asking volunteers to dwell in it in a guilt-ridden fashion. Dwelling in implication is about closing oneself off to one’s responsibilities, whilst reckoning with implication involves opening oneself to “one’s unacknowledged capacity to wound” (Rothberg Citation2019, 201). That defences are raised against such a vulnerable stance is not surprising; the masculinist account of self as sovereign, impregnable and autonomous demands constant defensive work to keep it in place. Part of maintaining this “seemingly sturdy and self-centred form of the thinking ‘I’” requires maintaining control, rather than moving towards others and being open to the uncomfortable things they have to say (Butler Citation2016, 24).

It could be argued that British subjects are implicated regardless of whether they recognize their implication or not. Yet, as stated in this essay, interpellation involves a call, turn, response and a “become”. Khoury (Citation2022), as also noted above, stated that Palestinians do not really have a choice about whether to remember or forget the past. International activists, conversely, have more of a choice about how they respond to the call to consider their place within structures of imperialism. As far as the activists I interviewed in this project were concerned, they, like the Quaker Margret Emmott, had had the privilege to be able to travel to the oPt.Footnote4 Once there and in encounters like those discussed above, the choice is then theirs as to whether they remain open and responsive to the call to reckon with interpellation, or not. In response to the ongoing situation of quotidian violence, Palestinians also perform acts of “ongoing refusal” of settler-colonialism (Barakat Citation2021, 92). Asking British activists to reckon with their implication because of the Balfour Declaration could thus also be seen as a way in which British citizens are invited to join in with Palestinians who remember in order to resist (Hawari Citation2018). Inviting British subjects to see in the same way Palestinians do is then an invitation for volunteers to participate in the ongoing Palestinian refusal; and, implicit in this is the invitation to assume a more political solidarity subject position than that demanded by the “anti-politics” of “benevolent” human rights activism (Tabar Citation2016). In the Palestinian demand for an apology, then, is an invitation to become and to refuse, meaning that these moments of interpellation are full of potential for shifting the power dynamics between Palestinians and British activists in transnational human rights work. Yet, as it has been shown, these encounters are part of a process which often involves both becoming and failing to become, hearing the call and failing to hear the call.

Acknowledgements

This work was made possible through Doctoral programme funding from the Economic Social Research Council. I would like to acknowledge the invaluable contributions made to various versions of this essay over the past few years by Professor Hagar Kotef, the SOAS postgraduate political theory workshop, Danilo Di Emidio, and several other friends and colleagues. I also want to thank the two peer reviewers for their very helpful feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This essay is based on interviews with and emails from British participants in the Ecumenical Accompaniment Programme in Palestine and Israel. In addition, the essay relies on retrospective participant observation with the same organisation which took place in 2017: the year of the Balfour Centenary in Palestine when the issue felt particularly live. All of the names of participants in this study have been replaced with pseudonyms.

2 The influence of the League of Nations is important to note. As Khalidi (Citation2020, 52) notes,

If it appeared that Palestinian pressure might force Britain to violate the letter or the spirit of the Mandate, there was intensive lobbying in the League’s Permanent Mandates Commission in Geneva to remind it of its overarching obligations to the Zionists.

3 However, Althusser admits that his narrative is limited in its accuracy of how ideology works. In reality these stages do not have a sequential nature:

The existence of ideology and the hailing or interpellation of individuals as subjects are one and the same thing … I must now suppress the temporal form in which I have presented the functioning of ideology, and say: ideology has always-already interpellated individuals as subject, which necessarily leads us to one last proposition: individuals are always-already subjects (Citation1984, 49).

4 Every year a significant number of international activists are prevented from entering Israel and thus the oPt. Some reports indicate that the frequency of those being barred entry is higher for people of colour and those with a Muslim-sounding name. See for example Hoque (Citation2012).

References

- Abu Hatoum, Nayrouz. 2021. “Decolonizing [in the] Future: Scenes of Palestinian Temporality.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 103 (4): 397–412. doi:10.1080/04353684.2021.1963806

- Ahmed, Sara. 2006. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Althusser, Louis. 1984. Essays on Ideology. London: Verso.

- Barakat, Rana. 2021. ““Ramadan Does Not Come for Free”: Refusal as New and Ongoing in Palestine.” Journal of Palestine Studies 50 (4): 90–95. doi:10.1080/0377919X.2021.1979376.

- Brah, Avtah. 2012. “The Scent of Memory: Strangers, Our Own and Others.” Feminist Review 100: 6–26. doi:10.1057/fr.2011.73.

- Butler, Judith. 1997. The Psychic Life of Power: Theories in Subjection. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Butler, Judith. 2016. “Rethinking Vulnerability and Resistance.” In Vulnerability in Resistance, edited by Judith Butler, Zeynep Gambetti, and Leticia Sabsay, 12–27. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Daswani, Girish. 2021. “The (Im)Possibility of Decolonizing Anthropology.” Everyday Orientalism (blog). 18 November. https://everydayorientalism.wordpress.com/2021/11/18/the-impossibility-of-decolonizing-anthropology/.

- Emmott, Margret. 1926–1927. Travel Diary, Margret Emmott Papers, Library of the Society of Friends, Friends House, London.

- Haraway, Donna. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575. doi:10.2307/3178066.

- Hawari, Yara. 2018. “Palestine Sine Tempore?” Rethinking History 22 (2): 165–183. doi:10.1080/13642529.2018.1451075.

- Hoque, Jakril. 2012. “Israel Denied Me Entry on the Basis of My Skin Colour and Religion.” The Electronic Intifada, 27 July. https://electronicintifada.net/content/israel-denied-me-entry-basis-my-skin-color-and-religion/11536.

- Kassem, Fatma. 2011. Palestinian Women: Narrative Histories and Gendered Memory. London: Zed Books.

- Khalidi, Rashid I. 2020. The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonial Conquest and Resistance. London: Profile Books.

- Khoury, Elias. 2022. “Finding a New Idiom: Language, Moral Decay, and the Ongoing Nakba.” Journal of Palestine Studies 51 (1): 50–57. doi:10.1080/0377919X.2021.2013024.

- Mahrouse, Gada. 2014. Conflicted Commitments: Race, Privilege, and Power in Transnational Solidarity Activism. Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Massad, Joseph Andoni. 2006. The Persistence of the Palestinian Question: Essays on Zionism and the Palestinians. London: Routledge.

- Morris-Suzuki, Tessa. 2004. The Past Within Us: Media, Memory, History. London: Verso.

- Rothberg, Michael. 2019. The Implicated Subject: Beyond Victims and Perpetrators. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Said, Edward W. 1979. Orientalism. New York: Vintage.

- Salih, Ruba. 2017. “Bodies That Walk, Bodies That Talk, Bodies That Love: Palestinian Women Refugees, Affectivity, and the Politics of the Ordinary.” Antipode 49 (3): 742–760. doi:10.1111/anti.12299.

- Sayigh, Rosemary. 2015. “Silenced Suffering.” Borderlands e-Journal 14 (1): 1–20.

- Shalhoub-Kevorkian, Nadera. 2014. “Human Suffering in Colonial Contexts: Reflections from Palestine.” Settler Colonial Studies 4 (3): 277–290. doi:10.1080/2201473X.2013.859979

- Shibli, Adania. 2012. “Of Place, Time and Language.” In In Seeking Palestine: New Palestinian Writing on Exile and Home, edited by Penny Johnson, and Raja Shehadeh, 62–69. New Delhi: Women Unlimited.

- Stein, Rebecca L. 2008. Itineraries in Conflict: Israelis, Palestinians, and the Political Lives of Tourism. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Stoler, Ann Laura. 2009. Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Commonsense. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Stoler, Ann Laura. 2016. Duress: Imperial Durabilities in Our Times. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Tabar, Linda. 2016. “Disrupting Development, Reclaiming Solidarity: The Anti-Politics of Humanitarianism.” Journal of Palestine Studies 45 (4): 16–31. doi:10.1525/jps.2016.45.4.16.

- Thompson, Janna. 2002. Taking Responsibility for the Past: Reparation and Historical Injustice. Cambridge: Polity.

- Yeğenoğlu, Meyda. 1998. Colonial Fantasies: Towards a Feminist Reading of Orientalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.