Through this editorial we introduce the fourth ‘theory special issue’ of Health, Risk and Society. The aim of the series, published more or less annually since 2014, is to provide a platform for theoretical development around core and emerging topics within social scientific studies of risk and uncertainty. By including original research articles alongside other formats, such as guest editorials or review articles, the previous special issues have sought to stimulate theorising, and reflection on theorising, through different ways of connecting theory to the empirical. We have sought to do something similar in this current special issue. By way of introduction to the special issue, we will first set out our conceptualisation of risk work and what this means for the foci of the articles included. We then proceed to set out some key intersections between the sociology of risk and uncertainty and the sociology of professions and professional work. These are pertinent for furthering understandings of risk work but also in understanding how studies of risk work can contribute to these wider fields, as is apparent from the studies within the issue. We will then briefly introduce these different studies, relating them to each other in terms of some common emerging themes, before concluding with some future theoretical and methodological directions, concerns and challenges.

Risk work in client-facing contexts – delineating the focus of this issue

The contributors to the previous theory special issue (volume 18: 7–8) addressed the topic of ‘dealing with uncertainty and risk in everyday practice’. The starting point of that collection was Zinn’s (Citation2008) consideration of different ways of handling uncertainty (e.g.risk, trust, hope, intuition) and various ways in which these approaches are combined or ‘bricolaged’ (Horlick-Jones, Walls, & Kitzinger, Citation2007) in everyday practices. There is therefore a strong connection between that issue and this current collection in that in our writing to date on ‘risk work’, which we have used to frame the special issue, we have been influenced by Zinn’s work alongside Horlick-Jones’s (Citation2005) use of ‘risk work’ to emphasise the pragmatic, situated manner by which risk and uncertainty are negotiated or handled in everyday working contexts – that is how this work ‘gets done’ (see Brown & Gale, Citation2018; Gale, Thomas, Thwaites, Greenfield, & Brown, Citation2016). But whereas Horlick-Jones (Citation2005) and another recent book on risk work (Power, Citation2016) consider these practices chiefly in terms of organisational power structures and agendas within these, our emphasis is far more on the workers themselves – their lived, embodied experiences and occupational identities, and how these relate to everyday practices – while still locating these within wider organisational and (para)professional power dynamics (Brown & Gale, Citation2018).

One further distinction (cf. Power, Citation2016) is that we are interested in client-facing,Footnote1 front-line (Harrits & Møller, Citation2014) or street-level (Gale, Dowswell, Greenfield, & Marshall, Citation2017, Lipsky, Citation1980) work where professionals are interacting and co-present with individual clients, patients or publics, and where they are required to interpret organisational policies and/or protocols on risk, with greater or lesser amounts of ‘discretionary space’. While ‘risk work’ in its wider organisational-management senses (e.g. Power, Citation2016) involves knowledge and protocol production, interpretation in relation to norms and rules, and the negotiation of social networks and hierarchies (see Power, Citation2016, p. 16; Labelle & Rouleau, Citation2016), what is distinctive about client-facing risk work is that it entails taking risk knowledge (as understood at the population level) and interpreting and applying it at the individual level (Heyman, Citation2010). It is at these moments when risk knowledge – as an abstract form of knowing made possible by the pooling of observations which are necessarily homogenised and lifted out of context – is re-embedded into social contexts that the implicit features of risk (values, categories, time-frames – Heyman, Alaszewski, & Brown, Citation2012; Szmukler, Citation2003) re-emerge as tensions (Brown & Gale, Citation2018). So whereas the difficulties in applying population knowledge to individual cases is well considered (see Heyman, Citation2010), our interest in risk work goes further to consider: (i) how the limits of risk knowledge in arriving at a decision or advice are overcome through other ways of handling uncertainty (Veltkamp & Brown, Citation2017; Zinn, Citation2008); (ii) how the inherently moral features of risk, in holding people accountable and as a homogenising cultural force (Douglas, Citation1990; Møller & Harrits, Citation2013), emerge more or less awkwardly within interactions with clients; and (iii) the ways in which these moral features of risk are handled can either alienate or enhance trust relations and communication (Brown & Calnan, Citation2013; Gale et al., Citation2017), with important implications for ongoing knowledge of and ability to assess individuals as risky or at-risk (Brown & Gale, Citation2018).

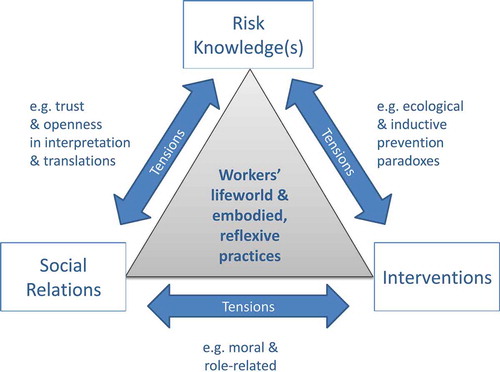

In elaborating these lines of inquiry, we have set out three core features of client-facing risk work – risk knowledge, interventions, social relations – the ways these relate to each other (as briefly outlined in points i to iii above), and the tensions that may often emerge around these, as captured in . At the centre of these are the embodied experiences and occupational identities of the workers themselves.

Figure 1. Core concepts and tensions in risk work (from Brown & Gale, Citation2018).

Locating risk work at the intersection of the sociology of risk and uncertainty and the sociology of professional work

Though by no means the only route to doing so (see Møller & Harrits, Citation2013), studying ‘risk’ as it is re-embedded in the social, paying particular attention to the awkward tensions which emerge, can tell us much about risk and its implicit categories, values and frames. Client-facing risk work is, therefore, not only of interest as an important emerging topic in its own right – impacting as it does the daily working lives of millions of practitioners, such as medical practitioners, nurses, public health workers, community health workers and social workers; police officers, auditors and accountants – but in what it can tell us about risk as a cultural and organisational category and mode of knowing (see Farre, Shaw, Heath, & Cummins, Citation2017).

Whereas the common assumption is that risk knowledge is first formulated, and then applied in everyday risk management practice, a number of articles in this special issue stress the way that risk is continually constructed and reconstructed within interactions and organisational contexts (see especially Farre et al., Citation2017; Hautomäki, Citation2018). Far from employing straightforward time-frames in handling risk, Hautomäki (Citation2018) shows how risk tools, such as standardised questionnaires, ‘materialise symptoms’ and shape a new understanding and experience of the condition for professionals and patients, (re)creating pasts and presents through the intervention. Rather than drawing upon risk knowledge to intervene in a distinct reality therefore, risk work intervenes through reconstructing the condition and experiences of it (see also Mol, Citation2002; van Loon, Citation2014), amid ongoing feedback between knowledge, intervention and social relations (as implied in ).

This destabilised relationship between risk and condition throws into doubt the possibility of knowing and neatly intervening in risk (Heyman, Citation2010); hence Hautomäki’s (Citation2018) use of the term ‘uncertainty work’. The tensions around risk which emerge when exploring risk work (see Brown & Gale, Citation2018) suggest, therefore, a reading of risk far closer to that of a material-semiotic or techno-semiotic approach (e.g. van Loon, Citation2014), one where risk must be reconstructed by professionals in conjunction with each other, with clients, with tools and technologies and various other actors (see Farre et al., Citation2017; Hautomäki, Citation2018). Yet the way in which risk interventions reshape their socio-material contexts – ‘matter, energy and information’ (van Loon, Citation2014, p. 444) – renders important limits to the control and power of professionals. Faced with these difficulties, alongside demands for control amid wider social discourses (Warner, Citation2006; Veltkamp & Brown, Citation2017), professionals’ experiences and practices may be characterised by vulnerability and a muddling through, more so than pursuing specific agendas amid discretionary space (cf. Power, Citation2016).

In turn, in terms of sociologies of professions and professional work, risk and its application – within existing and novel forms of organisations and features of (para)professional work within these – may be especially useful in illuminating power dynamics and cultural shifts as these take place within various reconfigurations of work and professional authority. Douglas (Citation1990), influenced by Gellner (Citation1984), argues that risk is a ‘political idiom’ which importantly epitomises key cultural dynamics – scientisation, globalisation, homogenisation – and is therefore an especially interesting object of study as a ‘fulcrum of change’ (Douglas, Citation1990, p. 3). Echoing this perspective, we have argued that if uncertainty and indeterminacy have always been a central challenge to, and resource of, professional power, then risk is a peculiarly modern means of negotiating uncertainty that reflects shifting dynamics of power and accountability within the organisational contexts where professionals increasingly work (Brown & Gale, Citation2018). In this sense we suggest that risk can be studied as an especially pertinent phenomenon for understanding reconfigurations of (para-)professional power and related experiences and identities, shedding important light on ‘jurisdictions’ of occupational power within organisations (compare with Bechky, Citation2003).

As argued by Douglas (Citation1990), one important way of approaching risk is as a forensic logic for holding members of social collectives accountable. The proliferation of risk across professional work and organisational contexts (Power, Citation2004) involves the shifting of accountability downwards, away from senior responsible figures and towards those working on the ‘front line’. In England, earlier Parliamentary conventions of ministerial responsibility, including norms of ministerial resignation following policy implementation scandals and policy failures, have disappeared. Rothstein (Citation2006) argues that risk management’s very popularity can be understood through the way it insulates senior figures from blame. Meanwhile, as Warner’s (Citation2006, Citation2015) studies of social workers undertaking risk work in England make clear, a shift in the way professionals are held accountable for care failings has left professionals increasingly vulnerable and, as a result, susceptible to media discourses which come to reconfigure their work through defensive practices. This shift in accountability via risk has significant implications for professional power and, in turn, for lived experiences of work, decision-making and identity amid these new power relations (see especially Brown & Gale, Citation2018; Farre et al., Citation2017; Warner, Citation2006).

Overview of articles in the special issue

In this section we provide a brief introduction to and overview of the special issue articles. This current issue (volume 20: 1–2) contains four original research articles (Chivers, Citation2018; Hautomäki, Citation2018; Iversen, Broström, & Ulander, Citation2018; Spendlove, Citation2018), alongside a tribute to the contribution of Tom Horlick-Jones to risk research (Alaszewski, Citation2018) - which we have placed at the start of the issue as Tom’s work is one central root of ‘risk work’ as an object of study - and a practice-oriented guest editorial by the outgoing Chief Social Worker of the city of Birmingham, England (Stanley, Citation2018), which considers the potential of more theoretical work to inform client-facing practice. Two further articles submitted for the special issue were published in an earlier issue (due to production reasons) and these (Farre et al., Citation2017; Turnbull, Prichard, Pope, Brook, & Rowsell, Citation2017) are also included in this overview. As well as briefly introducing each paper, we draw out key themes from each study which further build upon the key foci and intersections introduced above – the first three of the original articles that we discuss (Farre et al., Citation2017; Hautomäki, Citation2018; Iversen et al., Citation2018) teach us, above all, about how risk work gets done, and the challenges faced in accomplishing it. The other three original research articles (Chivers, Citation2018; Spendlove, Citation2018; Turnbull et al., Citation2017) focus more on the experience of risk work – an area we have previously noted is remarkably understudied (Gale et al., Citation2016) – and these articles contribute to understandings of professional power, roles, boundary work and identities. We conclude this section by moving to consider the further insights we can draw from the Stanley (Citation2018) contribution.

Tom Horlick-Jones (Citation2005) was the first, to our knowledge, to employ the concept of ‘risk work’ and, in his attentiveness to the practical logics of how risk is attended to in practical work settings, this special issue is in various senses indebted to his legacy. Alaszewski’s (Citation2018) essay illuminates the various roots of Tom’s research as these led to an exploration of risk work, partly in relation to his background in theoretical physics, his awareness of the limitations of the natural sciences in addressing risk, and his practical orientation towards influencing policies and practices on the ground.

More theoretically, Alaszewski (Citation2018) explores how this first distinctive exploration of risk work (Horlick-Jones, Citation2005) can be read as a positive critique and development of key arguments of Beck and Foucault. Horlick-Jones’s keen eye for the pragmatic practices and situational logics of police and healthcare professionals, inspired partly by ethnomethodology, show the limited pervasiveness of risk-orientations (compare with Beck, Giddens, & Lash, Citation1994) when studying organisations, for example whereby police officers pursue other goals than risk minimisation. Horlick-Jones (Citation2005) relates this to the limits of the pervasiveness of the (self-)surveillance processes of governmentality (drawing on Foucault, Citation1977 to critique some earlier Foucauldian arguments). Alongside an interest in what these client-facing professionals actually do, therefore, Horlick-Jones (Citation2005) emphasises the importance of language as a means of accounting for and justifying practices in ways which remain somewhat ‘autonomous’ from wider organisational discourses and scrutiny (Horlick-Jones, Citation2005, p. 296; Alaszewski, Citation2018). This ambivalent relationship of the practitioner to organisational and policy discourses is apparent in some of the studies in the special issue (see for example Farre et al., Citation2017; Iversen et al., Citation2018).

Iversen et al. (Citation2018) explore how Swedish healthcare professionals working with sleep apnoea patients negotiated their dual roles of providing patient-oriented care and assessing the risk their patients pose to the wider public in terms of potential traffic accidents caused by drowsiness and/or falling asleep. These two roles and responsibilities are set out in policy documents yet the authors underline the vagueness and lack of concrete directives as to what professionals should actually do. This ambiguity and uncertainty was then manifest in the practices and experiences of the risk work itself, as negotiated in interactions between professionals and patients.

Apposite to the analytical considerations introduced in the preceding section around risk as a fluid, elusive and fragile form of knowing, Iversen and colleagues draw attention to the defensive accounts given by patients which make professionals’ role of assessing risk particularly difficult to carry out. This defensiveness is interpreted as a reaction to the morally charged dynamics of the interactions; a consequence of the risk assessment components and the way patients are more or less implicitly being called to account for their behaviour. The subsequent difficulty facing professionals in assessing risk in such interactions was thus not only due to the (defensively) selective information being shared but, moreover, the patients’ reworking of professionals’ categories when accounting for their experiences and behaviours. The creation of ‘sub-categories’, which helped emphasise the ‘normalness’ of their experiences was an important way in which patient-actors sought to legitimise their practices (compare with Caiata Zufferey, Citation2012). Faced with this difficulty in knowing risk, Iversen and colleagues’ fine-grained conversation analysis (combined with interviews with professionals) is especially useful in drawing out how ambivalences and incoherencies emerge within professionals’ practices, by which risk and diagnosis become blurred and where risk is pragmatically circumvented through an orientation towards patient education. In this way the tensions underpinning the risk management policies and practices remain latent and are seldom confronted (see Brown & Gale, Citation2018).

Various findings emerging within Iversen and colleagues’ (Citation2018) research are echoed within the article of Hautomäki (Citation2018), drawing on her research into the lived experiences of patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder in Finland and of the professionals working with them. We have noted above that Hautomäki underlines the way in which risk oriented processes of intervening actually change the nature of these experiences, as these come to be (re)understood and accounted for by patients. The inherent yet implicit role of values, categories and time-frames within risk is illustrated in these articles: while Iversen and colleagues (Citation2018) draw our attention to how tensions in categories (re)emerge within the interactions through which risk is constructed, Hautomäki (Citation2018) focuses her analysis on different conceptions of time.

Tensions between the roles of assessing risk and caring are analysed by Hautomäki as manifest through contrasting formats of time – ‘clinical time’ and ‘experienced time’. These different modes of chronology – one ‘linear and standardised’, the other ‘embodied’, ‘cyclical and processual’ – involve different notions of care (Hautomäki, Citation2018) but also imply different possibilities for intervening. Interpreting risk in terms of clinical time suggests a simple-linear model of ‘risk’ (Renn, Citation2008), while the contrasting chronology of experienced time implies much greater levels of ‘ambiguity’ around values attached to different outcomes, ‘complexity’ regarding the number of factors interacting to shape outcomes, alongside ‘residual’ uncertainty (Renn, Citation2008). Hautomäki’s (Citation2018) usage of ‘uncertainty work’ (see also preceding section) is thus further legitimated in reading her study in light of critical risk governance research (Renn, Citation2008). Understood in this way, professionals are not only seeking to negotiate the different ‘logics of care’ concurrent with these two chronologies (Hautomäki, Citation2018; drawing partly on Mol, Citation2008) but can be seen as vulnerable in their attempt to negotiate between two contrasting ontologies of risk, with their attendant epistemological assumptions and work-place pressures.

Professionals’ awkward position amid such risk work, characterised as it is by tensions which usually remain veiled (Brown & Gale, Citation2018), has important implications for lived experiences of everyday work. Farre, Shaw, Heath and Cummins’s (Citation2017) study of professionals’ risk-related practices around medicine-safety frameworks in the English National Health Service note the heavy burden that risk and related dynamics of blame impose on healthcare professionals, where concerns about medicines-errors are bound up with understandings of professional roles and identity (Farre et al., Citation2017). Once again (compare with Iversen et al., Citation2018), we see a working environment which, owing to the structures of accountability and blame bound up with risk governance, becomes morally charged in ways which need to be negotiated by professionals as they interact directly with the ‘object at risk’ – the patient (Farre et al., Citation2017, p. 222).

Partly influenced by the work of Douglas (as we introduced earlier), Farre and colleagues’ study most usefully draws attention to the nature of risk work contexts as being characterised simultaneously by uncertainty, regarding ‘are we doing the right thing?’ and moral ambiguity, regarding ‘who is responsible here?’ Partly consonant with Zinn (Citation2008) therefore, the authors follow Luhmann in denoting ‘elements, such as hope, opportunity, uncertainty and frankness that determine the situation in which a decision was taken’ (Luhmann, Citation1993, p. 193, cited in Farre et al., Citation2017, p. 221), but show that these further logics are ways of dealing with the structures of accountability as much as they are means for handling uncertainty to reach a decision. Questioning ideals of an ‘individualist, rational, responsible self’, Farre and colleagues ‘illustrate how the collective, interactional nature of risk-related practices, where core elements, such as underpinning rationales and responsibility are contested and negotiated, were defining features of medication safety-in-action in the context of routine practice’ (Farre et al., Citation2017, p. 221).

In the next part of this section we move on to three papers that focus more directly on the experience of doing risk work and its implications for the negotiation of professional, occupational and personal identities. These articles begin the process of ‘writing the practitioner back in’ to our scholarship on risk (Chivers, Citation2018).

The article by Turnbull and colleagues (Citation2017) explores the everyday work of managing risk in the context of telephone medical assessments (as part of the English NHS 111 service) with the use of a computer decision support system. This article argues that technologies of risk – such as the decision support system they examine – enable risk work to be carried out outside the domain of professionals. The indeterminacy that characterises professional work (Jamous & Peloille, Citation1970) is apparently edited out through the technology, meaning that non-clinical staff without specialist risk knowledge can be substituted. However, a more complex picture emerges in practice; Turnbull and colleagues explore how, for these lower-status workers, ensuring that the risk work gets done involves making the technology work for real life situations. This is experienced by the call handlers as a heavy responsibility – a matter of life and death, rather than ‘just a call centre job’. A standardised, evidence-based model of risk knowledge is programmed into the technology but risk is always more than what can be measured and the call handlers must ‘mop up’ the residual uncertainty, working collaboratively with the technology and applying it through the lens of their own ‘common sense’. As the authors put it, ‘risk work is not “in the machine” or “in the call handler” but it is accomplished by both’.

Spendlove’s (Citation2018) article in this issue also explores the issues of professional boundaries and professional skill required in the management of risk, but through looking at the work of midwives and obstetricians in maternity care in England. Unlike Turnbull and colleagues (Citation2017) who examine workforce substitution to deliver risk work, Spendlove (Citation2018) examines how, as risk work is given greater emphasis within the clinical environment, the boundaries between midwifery and medical care shift and adapt – and the impact of that on the practitioners themselves. Spendlove’s exploration of the closeness of ‘risk’ with the notion of ‘blame’ in the experiences of professionals enables her to explain how this provokes defensive practice and how this materially changes the nature of the care provided and by whom. The need to demonstrate that risk minimisation is taking place, using paperwork as evidence, ironically takes time away from patient-facing caring work. This results in ideological and practical tensions, particularly for the midwives with their occupational identity being bound up with the idea of natural birth, which is at odds with the concept of risk. This leads to areas of practice with greater uncertainty or indeterminacy being transferred to the obstetricians. In this article, we see again how the tensions in risk work are veiled in everyday practice (Brown & Gale, Citation2018). Despite uncertainties in the evidence-base, the ever growing reliance on ‘evidence’ of risk – and the need to be able to audit risk decisions – means that practitioners feel anxiety about potential ‘blame’ and adapt their referral practices accordingly, rather than overtly challenging or resisting this evidence. This limits their ability to apply their tacit or embodied knowledge about the risks (which are not auditable in the same way) acquired through practical experience. The indeterminacy of professional work is being driven out. Indeed, Spendlove argues that, ultimately, the greater dominance of risk in the everyday work of maternity units has the potential to lead to the deprofessionalisation of midwifery.

Continuing this theme, Chivers (Citation2018) explores these issues of the growing influence of risk in professional practice in the context of social work as it grapples with new risk discourses around extremism and radicalisation. Echoing Spendlove’s observations of the tensions between an ethos of natural birth and the risks of childbirth, Chivers explores the tensions for a profession, with a commitment to supportive and holistic social care for families and communities, which is being asked to apply individualised risk assessments. Working explicitly through a Habermasian theoretical lens, she uses the tensions that emerge in risk work (Brown & Gale, Citation2018) as a starting point for exploring and theorising how these are experienced and addressed. She explores the consonance and dissonance of different aspects of risk work with other aspects of the social work professional identity. One mechanism for resolving apparent tensions is to translate the ‘risk of radicalisation’ into a form that is more familiar and quotidian in practice – safeguarding or the risk of abuse, for instance. However, a key finding from the interviews conducted by Chivers is that the need to address or engage with potential tensions can relatively easily be suspended and remain unreflected upon in the midst of a busy daily practice until an actual event requires action. In the meantime, pre-existing assumptions and tacit knowledge are drawn upon to manage everyday action. Chivers argues that where there is dissonance between social work ethos and practice in the context of risk work, there is the opportunity for either resistance or ‘bracketing off’. She interprets the latter as a method for minimising the tensions of risk work through the colonisation of the professional’s lifeworld (Habermas, Citation1987) by risk, in a way that leaves things unchanged, unchallenged, or ‘veiled’.

A final important emerging finding from Chivers’ work and indeed one that could be explored in future studies of risk work – although Chivers is careful not to make unwarranted generalisations from her own sample – are the other aspects of personal identity that one brings to work. Beyond professional or occupational role identity, the worker also has a gender identity, an ethnic identity, a religious identity, and a sexual orientation amongst other characteristics. Assessments of risk (based as they are on population science or assessments of groups) tend to group ‘types of people’ together by certain characteristics and if workers share that ‘risky’ identity, doing risk work can be experienced as disruptive to that identity, or they may feel they have to defend it. Equally, they may feel uncomfortable with the thin line between acting towards a member of a group in a certain way on the basis of levels of risk calculated for them (somewhere else – in a laboratory, or in the police service for instance) and the tendency to then stereotype or discriminate against people who belong, or appear to belong, to that identity group.

These latter three papers drive forward our understanding of the impact of risk work on the experiences, lifeworlds and occupational identities of the (para)professionals and other workers who are finding that risk work is an ever more substantial part of their daily practice (such as the social workers or maternity care professionals) or, indeed, that their jobs were created to deal with issues of risk (such as the call handlers at NHS 111).

At the end of this special edition, we have included a practice review, by Stanley (Citation2018) who applies the theories of risk work that have been further developed in this special issue to questions of social work practice. Across different academic cultures, there is a growing interest in the implications or impact of the research that social scientists do. It is not always easy to make direct links between theoretical innovation (that these Health, Risk and Society Special Issues have sought to drive forward) and changes to policy or practice. However, Stanley deftly shows why theory ought to matter to social workers and how it might be used pragmatically and practically.

He builds particularly on the concerns raised in Chivers’ (Citation2018) article, on the implications of the PREVENT duty on social workers – to identify and support vulnerable adults and children at ‘risk’ of radicalisation. He explores how the idea of radicalisation risk is problematic. Stanley uses the theoretical observations developed in this special edition about the ways in which tensions in risk work often remain veiled to call for a more critical social work practice.

Risk work: some potential avenues of further research

We conclude this editorial with some reflections on where researchers interested in risk work might go next, beyond themes emerging in this special edition, theoretically and methodologically. The focus of this special edition is theory and certainly there are key theoretical themes that have emerged and would warrant further exploration, including in other empirical contexts. The articles here focus on risk in the domains of health and social care, but risk – as it interacts directly with clients or end users – is also to be found in many other social spaces, such as crime and policing, manufacturing and industry, and politics. We have also seen a diversity of methodological approaches to empirical work (see Gale et al., Citation2016 for a call for this) in this special edition (ethnomethodology, ethnography, phenomenology) each bringing specific insights to the theoretical concerns of risk work. In their article, Iversen and colleagues (Citation2018) particularly emphasise their methodological contribution – how the use of conversation analysis demonstrates that risk work is a joint accomplishment between worker and client. Chivers (Citation2018) interview study explores the nuances of how risk work can remain on the edge of conscious professional reflection – both a practical strategy in the face of high workloads, as well as a strategy to avoid having to unveil the tensions between professional ethos and what they are required to do statutorily in terms of risk assessments. Hautomäki’s (Citation2018), Spendlove’s (Citation2018), Turnbull and colleagues’ (Citation2017) and Farre and colleagues’ (Citation2017)’s articles each use a combination of qualitative methods, but an important component in all of them is (non-)participant observation. This allows for a close examination of what is actually done as practitioners engage in risk work, which is an important counter balance to data of self-reported activity and action (Horlick-Jones, Citation2005).

The focus of the special edition on bringing the practitioner back into our analysis of risk, through a dialogue with debates in the sociologies of work, employment and professions, has raised questions both about the practical accomplishment of risk work – the knowledge, skills and approaches for ‘everyday action’ (to use Horlick-Jones’s Citation2005 term) – and the impact of (expanding) risk work on ‘the ways that workers forge their own professional and personal identities’ (Gale et al., Citation2016, p. 1065). Common to all the articles is an acknowledgement of the limitations of risk knowledge in accounting for all that practitioners feel and do in their work – Hautomäki’s (Citation2018) choice to develop the concept of ‘uncertainty work’ stresses this. Yet, the discursive hold of risk shows no signs of abating, particularly in the fields of health and social care where evidence-based practice is venerated.

As we see the development of greater specificity in risk calculations, greater reliance on risk logics in policy and greater development of risk technologies, inevitable questions will emerge about who should be doing this work and what skills and training are necessary. Will we see wholesale movement towards workforce substitution as risk is seen as a viable technocratic application of standardised decision-making, or will we see existing professions shifting their remit towards embracing specialised or personalised approaches to managing risk? As extensions of (para)professional responsibilities into new forms of risk work become more common, will reflexivity towards risk diminish (as addressed by Chivers, Citation2018)? If risk logics become even more dominant, will the scope for resistance be attenuated or will it stimulate a backlash of resistance (see Brown, Citation2011)?

As we have argued in this editorial and elsewhere, key political dynamics around these wider professional, human resource and organisational shifts become manifest within the various (veiled) tensions which are discernible within various client-facing risk work practices and experiences (Brown & Gale, Citation2018). Attentiveness to these tensions – their potential to alert us to wider, previously neglected political dynamics around risk, as well as the various processes by which tensions are negotiated and overlooked – would appear to be an important avenue of future research around risk work. Further ways of combining different qualitative and ethnographic methods to more accurately capture the practices and experiences of risk work will be important in such work. Insights from ‘classic’ studies of risk (Beck et al., Citation1994; Douglas, Citation1992; Luhmann, Citation1993) will remain an important conceptual and analytical resource but important further purchase can be added by following Horlick-Jones’s (Citation2005, p. 294) orientation towards specific situated practices and the way in which ‘formal accounts’ and ‘informal logics’ relate to one another. We would argue, in turn, that the ambivalences emerging between formal and informal accounts are one of several forms of tensions which characterise the practices and experiences of risk work (Brown & Gale, Citation2018).

The nature of these practices, experiences and tensions, and their relationship to wider organisational-political dynamics, can be explored further by harnessing: first, insights into the lifeworlds of those undertaking risk work, and their colonisation. While initial work to extend Habermasian theory (see Brown & Gale, Citation2018; Chivers, Citation2018) has focused largely on lifeworlds, there is much to be learned from a deeper consideration of system-lifeworld processes, not least in digging into the Marxian (work-oriented) and Weberian (possibilities for ‘rationalisation’) foundations of the approach; second, an attentiveness to the embodied nature and habitus of practices and experiences and their location within particular organisational (and professional) fields. This would allow for further analysis of issues such as resistance to formal risk narratives or the nature of the communications that take place within clinical and social care contexts (Broom, Broom, & Kirby, Citation2014; Crossley, Citation2004); and/or, third, the potential for combining these two lines of exploring and interrogating risk work.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the special issue contributors, reviewers and to Andy Alaszewski for their hard work in bringing the special issue into being as well as for the fruitful dialogues which have emerged around these studies. Hannah Bradby, Christian Bröer, Nienke Slagboom, Gareth Thomas, Sheila Greenfield, Rachael Thwaites and several others took part in two workshops which were constructive in the development of our thinking around the topic, as is reflected in this editorial. These meetings and further empirical, theoretical and practice-oriented work were made possible by grants from the Foundation for the Sociology of Health and Illness ('Towards a sociology of risk work in health' - Research Grant Development Award) and the Economic and Social Research Council ('Negotiating the tensions in everyday risk work: a workforce development tool for health and social care' - Impact Acceleration Account grant).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. We use the term ‘client facing’, because like Harrits and Møller (Citation2014) we have chosen to avoid some aspects of Lipsky’s ‘bureaucrat’ term. Not only may many professionals not identify as ‘bureaucrats’, but we argue that our framework is relevant for analyses of professionals working far beyond the usual welfare state contexts with which Lipsky’s term is usually associated. Moreover, while street-level bureaucrats are typically thought of, following Lipsky, in relation to their use of discretionary space, our framework is conceived with many weaker professionals and para-professionals in mind, whereby there is significant variation in the extent of discretion available to these workers. We prefer, however, to avoid the ‘front line’ term due to the metaphorical associations of this term.

References

- Alaszewski, A. (2018). Tom Horlick-Jones and risk work. Health, Risk & Society, 20(1). this issue.

- Bechky, B. (2003). Object lessons: Workplace artefacts as representations of occupational jurisdictions. American Journal of Sociology, 109(3), 720–752. doi:10.1086/379527

- Beck, U., Giddens, A., & Lash, S. (1994). Reflexive modernisation: Politics, tradition and aesthetics in the modern social order. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Broom, A., Broom, J., & Kirby, E. (2014). Cultures of resistance? A Bourdieusian analysis of doctors’ antibiotic prescribing. Social Science & Medicine, 110, 81–88. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.030

- Brown, P. (2011). The concept of lifeworld as a tool in analysing health-care work: exploring professionals’ resistance to governance through subjectivity, norms and experiential knowledge. Social Theory & Health, 9(2), 147–165. doi: 10.1057/sth.2011.3

- Brown, P., & Calnan, M. (2013). Trust as a means of bridging the management of risk and the meeting of need: A case study in mental health service provision. Social Policy & Administration, 47(3), 242–261. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9515.2012.00865.x

- Brown, P., & Gale, N. (2018). Theorising risk work: Analysing professionals’ lifeworlds and practices. Professions & Professionalism, 8(1), e1988.

- Caiata Zufferey, M. (2012). From danger to risk: Categorising and valuing recreational heroin and cocaine use. Health, Risk & Society, 14(5), 427–443. doi:10.1080/13698575.2012.691466

- Chivers, C. (2018). “What is the headspace they are in when they are making those referrals?” Exploring the lifeworlds and experiences of health and social care practitioners undertaking risk work within the prevent strategy. Health, Risk & Society, 20(1). this issue.

- Crossley, N. (2004). On systematically distorted communication: Bourdieu and the socio‐analysis of publics. The Sociological Review, 52(s1), 88–112. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2004.00475.x

- Douglas, M. (1990). Risk as a forensic resource. Daedalus, 119(4), 1–16.

- Douglas, M. (1992). Risk and blame: essays in cultural theory. London: Routledge.

- Farre, A., Shaw, K., Heath, G., & Cummins, C. (2017). On doing ‘risk work’ in the context of successful outcomes: Exploring how medication safety is brought into action through health professionals’ everyday working practices. Health, Risk & Society, 19(3–4), 209–225. doi:10.1080/13698575.2017.1336512

- Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. London: Allen Lane.

- Gale, N., Dowswell, G., Greenfield, S., & Marshall, T. (2017). Street-level diplomacy? Communicative and adaptive work at the front line of implementing public health policies in primary care. Social Science & Medicine, 177, 9–18. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.046

- Gale, N., Thomas, G., Thwaites, R., Greenfield, S., & Brown, P. (2016). Towards a sociology of risk work: A narrative review and synthesis. Sociology Compass, 10(11), 1046–1071. doi:10.1111/soc4.12416

- Gellner, E. (1984). Nations and nationalism. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Habermas, J. (1987). Theory of communicative action (Vol. II). Cambridge: Polity.

- Harrits, G. S., & Møller, M. O. (2014). Prevention at the front line: How home nurses, pedagogues, and teachers transform public worry into decisions on special efforts. Public Management Review, 16(4), 447–480. doi:10.1080/14719037.2013.841980

- Hautomäki, L. (2018). Uncertainty work and temporality in psychiatry: How clinicians and patients experience and manage risk in practice? Health, Risk & Society. this issue.

- Heyman, B., Alaszewski, A., & Brown, P. (2012). Health care through the ‘lens’ of risk and the categorisation of health risks – an editorial. Health, Risk & Society, 14(2), 107–115.

- Heyman, B. (2010). Health risks and probabalistic reasoning. In B. Heyman, A. Alaszewski, M. Shaw, & M. Titterton (Eds.), Risk, safety and clinical practice: Healthcare through the lens of risk (pp. 85–106). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Horlick-Jones, T. (2005). On ‘risk work’: Professional discourse, accountability, and everyday action. Health, Risk & Society, 7(3), 293–307. doi:10.1080/13698570500229820

- Horlick-Jones, T., Walls, J., & Kitzinger, J. (2007). Bricolage in action: Learning about, making sense of, and discussing, issues about genetically modified crops and food. Health, Risk & Society, 9(1), 83–103. doi:10.1080/13698570601181623

- Iversen, C, Broström, A, & Ulander, M. (2018). Traffic risk work with sleepy patients: from rationality to practice. Risk & Society, 20 (1–2).this issue.

- Jamous, H., & Peloille, B. (1970). Professions or self-perpetuating systems? Changes in the French university-hospital system. In J. A. Jackson (Ed.), Professions and professionalization (pp. 111–152). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Labelle, V., & Rouleau, L. (2016). Doing institutional risk work in a mental health hospital. In M. Power (Ed.), Riskwork: Essays on the organizational life of risk management (pp. 211–231). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lipsky, M. (1980). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public service. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Luhmann, N. (1993). Risk: A sociological theory. New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter.

- Mol, A. (2002). The body multiple: Ontology in medical practice. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Mol, A. (2008). The logic of care. Health and the problem of patient choice. London: Routledge.

- Møller, M., & Harrits, G. (2013). Constructing at-risk target groups. Critical Policy Studies, 7(2), 155–176. doi:10.1080/19460171.2013.799880

- Power, M. (2004). The risk management of everything: Rethinking the politics of uncertainty. London: Demos.

- Power, M. (2016). Introduction – risk work: The organisational life of risk management. In M. Power (Ed.), Riskwork: Essays on the organizational life of risk management (pp. 1–25). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Renn, O. (2008). Risk governance: Coping with uncertainty in a complex world. London: Earthscan.

- Rothstein, H. (2006). The institutional origins of risk: A new agenda for risk research. Health, Risk & Society, 8(3), 215–221. doi:10.1080/13698570600871646

- Spendlove, Z. (2018). Risk and boundary work in contemporary maternity care: Tensions and consequences. Health, Risk & Society, 20(1–2). this issue.

- Stanley, T. (2018). The relevance of risk work theory to practice: The case of statutory social work and the risk of radicalisation in the UK. Health, Risk & Society, 20(1–2). this issue.

- Szmukler, G. (2003). Risk assessment: Numbers and values. Psychiatric Bulletin, 27(6), 205–207. doi:10.1017/S0955603600002257

- Turnbull, J., Prichard, J., Pope, C., Brook, S., & Rowsell, A. (2017). Risk work in NHS 111: The everyday work of managing risk in telephone assessment using a computer decision support system. Health, Risk & Society, 19(3–4), 189–208. doi:10.1080/13698575.2017.1324946

- van Loon, J. (2014). Remediating risk as matter–Energy–Information flows of avian influenza and BSE. Health, Risk & Society, 16(5), 444–458. doi:10.1080/13698575.2014.936833

- Veltkamp, G., & Brown, P. (2017). The everyday risk work of Dutch child-healthcare professionals: Inferring ‘safe’ and ‘good’ parenting through trust, as mediated by a lens of gender and class. Sociology of Health & Illness, 39(8), 1297–1313. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.12582

- Warner, J. (2006). Inquiry reports as active texts and their function in relation to professional practice in mental health. Health, Risk & Society, 8(3), 223–237. doi:10.1080/13698570600871661

- Warner, J. (2015). The emotional politics of social work and child protection. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Zinn, J. (2008). Heading into the unknown: Everyday strategies for managing risk and uncertainty. Health, Risk & Society, 10(5), 439–450. doi:10.1080/13698570802380891