ABSTRACT

Cognitive symptoms are prevalent in patients with functional neurological disorder (FND). Several studies have suggested that personality traits such as neuroticism may play a pivotal role in the development of FND. FND has also been associated with alexithymia: patients with FND report difficulties in identifying, analyzing, and verbalizing emotions. Whether or not alexithymia and other personality traits are associated with cognitive symptomatology in patients with FND is unknown. In the current study, we explored whether the Big Five personality model factors (neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness) and alexithymia were associated with cognitive functioning in FND. Twenty-three patients with FND were assessed using a neuropsychological assessment and questionnaire assessment to explore personality traits (Neuroticism-Extraversion-Openness Five-Factor Inventory) and alexithymia (Bermond-Vorst Alexithymia Questionnaire). The results indicated that high conscientiousness was associated with lower planning scores (ρ = −0.52, p = .012) and high scores on alexithymia were associated with lower scores on verbal memory scores (ρ = −0.46, p = .032) and lower sustained attention scores (ρ = −0.45, p = .046). The results did not remain significant after controlling for multiple testing. The preliminary results of our study suggest that personality and cognitive symptomatology in patients with FND are topics that should be further explored in future studies, as cognitive symptomology can affect treatment results.

Introduction

Functional neurological disorder (FND), or conversion disorder, includes a wide range of neurological deficits that, after neurological evaluation, lack an organic or physiological basis. FND is diagnosed using positive signs such as intermitted gait abnormalities, huffing and puffing sign, give-away weakness of the legs, and more (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2022). Clinical presentations of FND include sensory, motor, or cognitive symptoms that cause impairments to the individuals suffering from these symptoms (Carson et al., Citation2011). Patients with FND often experience substantial cognitive symptoms (e.g., L. B. Brown et al., Citation2014; de Vroege et al., Citation2021) in comparable amounts to patients with other somatic symptom and related disorders (see for instance, de Vroege et al., Citation2018; Inamura et al., Citation2015).

Several psychological factors and/or predictors of FND have been suggested, such as acute stressors and trauma (Bodde et al., Citation2009; Carson et al., Citation2016), but other possible contributing factors remain to be explored. Exploring contributing factors is a first step in understanding underlying mechanisms, which helps to effectively diagnose and treat patients with FND. According to a systematic review by McWhirter et al. (Citation2020), there is a lack of studies focusing on psychological factors that may be related to symptomatology in functional cognitive disorder (the subtype of FND with cognitive symptomatology as its primary symptom) and other phenotypes of FND. In this study, we investigated personality factors derived from the “Big Five Personality Model” and alexithymia as two possible factors related to cognitive functioning in patients with FND. Previous studies showed that personality factors are associated with somatic symptoms (e.g., Curtis et al., Citation2015; Langguth et al., Citation2007; Paine et al., Citation2009), where it is thought that certain personality factors may contribute to a false attribution of physical sensations or increased sensation in the body, and can play a pivotal role in maintaining physical symptomatology (Menon et al., Citation2018; Mostafaei et al., Citation2019).

The current literature provides some insights into the role of personality in FND symptomology. Personality, as conceptualized with the widely accepted Big Five Personality Model, is considered a construct of five dimensions: neuroticism, openness, extraversion, conscientiousness, and agreeableness (Costa & McCrae, Citation1995; John & Srivasstava, Citation1999). These personality factors are suggested to influence emotion regulation (Hughes et al., Citation2020) and, therefore, offer prognostic factors to tailor specific interventions (M. K. Williams et al., Citation2023). Several studies have shown that differences exist in personality factors between patients with FND versus individuals without FND (Bodde et al., Citation2011; Hallet et al., Citation2022; Jalilianhasanpour et al., Citation2018; Jungilligens et al., Citation2022; Testa et al., Citation2007). Neuroticism is considered a personality trait which is characterized by proneness to experience negative affect, anxiety, and emotional instability. Regarding neuroticism, individuals with FND tend to exhibit higher levels in comparison to healthy controls (Perez et al., Citation2021), but patients with functional memory disorder scored equally high on neuroticism compared to controls in one study (Metternich et al., Citation2009). Neuroticism is frequently linked to the occurrence and severity of functional neurological symptoms (e.g., Ekanayake et al., Citation2017). A high susceptibility to stress and, as a result, heightened bodily perception, may contribute to the manifestation of FND.

Other personality traits, such as extraversion and openness to experience, have also been investigated in relation to FND. Individuals with FND tended to exhibit lower levels of extraversion and openness to experience (Jalilianhasanpour et al., Citation2018; Stone et al., Citation2020; Tomić et al., Citation2017). A lower openness to experience (e.g., less preference for imagination, creativity, and intellectual curiosity) may contribute to the development of FND symptoms, through heightened sensitivity to internal and external stimuli. Extraversion, characterized by sociability, assertiveness, and positive affect, has been proposed as a protective factor, rather than a contributing factor, in the development and persistence of FND (Jalilianhasanpour et al., Citation2018). As of yet, no studies have corroborated these hypotheses.

To what extent cognitive symptomatology can be attributed to personality factors is debated on. In patients with functional seizures, cognitive performance has been linked to several psychological and personality factors (Willment et al., Citation2015). With regards to healthy individuals (Bates & Rock, Citation2004; Eysenck, Citation1974; Murdock et al., Citation2013; Sutin et al., Citation2019; P. G. Williams et al., Citation2010) and people with somatic symptom and related disorders (Bartkowska et al., Citation2018; de Vroege et al., Citation2022), results are equivocal. In healthy individuals, neuroticism was primarily associated with executive functioning, extraversion with information processing speed and memory, and openness with information processing speed, memory, and executive function (Bates & Rock, Citation2004; Eysenck, Citation1974; Murdock et al., Citation2013; Sutin et al., Citation2019; P. G. Williams et al., Citation2010). Neuroticism, extraversion, and openness were associated with planning and (visual) memory in patients with somatic symptom and related disorders (Bartkowska et al., Citation2018; de Vroege et al., Citation2022).

Besides the Big Five personality factors, alexithymia can also be considered as a personality trait. Alexithymia is characterized by having trouble with identifying, experiencing, and analyzing emotions, and with communicating about emotional states (Nemiah & Sifneos, Citation1970; Sifneos, Citation1973). Alexithymia has been linked to psychosomatic disorders (Kellner, Citation1990; Koelen et al., Citation2015; Rief & Broadbent, Citation2007; Taylor et al., Citation1999; Waller & Scheidt, Citation2006) and to executive functioning in healthy participants (Santorelli & Ready, Citation2015). Alexithymia can contribute to the development of FND through interpersonal conflicts, which have been suggested to occur prior to the development of FND (Edwards & Bhatia, Citation2012; Morsy et al., Citation2022; Reuber et al., Citation2007). In FND, alexithymia has been described by some researchers to predict symptomatology (R. J. Brown et al., Citation2013; Demartini et al., Citation2014; Kaplan et al., Citation2013). Alexithymia may be explanatory for experiencing cognitive symptoms through somatosensory amplification, in which interoceptive arousal is misattributed by alexithymic patients (Perez et al., Citation2015). To which extent alexithymia is related to cognitive symptoms in FND is not yet known.

To the best of our knowledge, the relation between personality and cognitive functioning in FND has only been studied once (Metternich et al., Citation2009), where patients had a higher score on neuroticism than healthy controls, which was highly related to memory performance. In the current study, we investigated the Big Five personality traits and alexithymia as possible factors contributing to cognitive dysfunction in patients with FND. We included patients with FND (e.g., functional seizures, faints, and paralysis) with subjective cognitive concerns, instead of focusing on FND patients with solely cognitive symptoms (functional cognitive disorder). We hypothesized that in patients with FND a high level of neuroticism and alexithymia, and lower levels of extraversion and openness would be associated with lower levels of cognitive functioning. Since this is the first study to explore the association between personality/alexithymia and cognitive functioning in patients with FND, we were unable to hypothesize about specific cognitive domains. We did not expect any associations between agreeableness/conscientiousness and cognitive test scores.

Methods and materials

Setting and participants

This cross-sectional study consisted of a dataset of consecutive patients with FND that was used for retrospective examination. Data from 2014 to 2017 was used. Participants were included if they had a diagnosis of FND according to the DSM criteria (APA, Citation2000, Citation2013, Citation2022) and had completed a neuropsychological assessment. Participants were excluded in case of malingering, insufficient mastery of the Dutch language, or in case of psychosis or acute suicidality. All participants were referred to our Clinical Centre of Excellence for somatic symptom and related disorders. FND diagnosis was based on previous evaluations by neurologists (available in the referral letters), that consisted of magnetic resonance imaging scans, electroencephalograms, or computer tomography that were conducted prior to referral to our facility to our department. The DSM diagnosis was made by a psychiatrist after clinical psychiatric evaluation, in which all neurological (and other) information was used, and confirmed during a multidisciplinary team discussion in which all available information was discussed and taken into consideration. Before intake, patients were informed by letter that their data could be used for scientific purposes (during intake they could decline the use of their data). Not consenting had no consequences for treatment. The scientific committee of GGz Breburg approved of this study (CWO 2019–05).

Measures

Several measures were included regarding personality, alexithymia, and neurocognitive functioning.

Personality

The Neuroticism-Extraversion-Openness Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) was used to measure personality according to the Big Five Personality Model (Costa & McCrae, Citation1995). This self-report questionnaire comprises 60 items, which are scored on a 5-point Likert scale. Prior studies showed that the psychometrics of the NEO-FFI are good to excellent for all subscales (Costa & McCrae, Citation1995).

Alexithymia

The Bermond-Vorst Alexithymia Questionnaire (BVAQ) was used to measure alexithymia in terms of five dimensions of alexithymia; identifying (identification of emotions), verbalizing (verbalize or express emotions), analyzing (ability to analyze emotions), fantasizing (fantasize), and emotionalizing (tendency to become emotional) (Bermond et al., Citation2006; Vorst & Bermond, Citation2001). This self-report questionnaire consists of 40 questions which can be answered on a 5-point Likert scale. Higher scores are interpreted as higher levels of alexithymia. It is possible to calculate a cognitive and affective dimension of alexithymia (Bermond et al., Citation2010) but a recent validation study showed that the use of the five subscales is preferred (de Vroege et al., Citation2018b). Due to the small sample size, we used the total score of the BVAQ in our analyses to limit the number of conducted analyses.

Neuropsychological assessment

Neurocognitive functioning was assessed using a neuropsychological assessment conducted by trained (neuro)psychologists. First, malingering was assessed with the Test of Memory Malingering (Tombaugh, Citation1996) and/or the Amsterdam Short Term Memory Test (Schmand & Lindeboom, Citation2005) (see de Vroege et al. (Citation2018) for the complete malingering protocol).

Information processing speed was assessed using the raw total score of the Digit Symbol Substitution Test from the fourth edition of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-IV; Wechsler, Citation2008). Divided attention was assessed using the total time to complete the Trail Making Test-B (TMT; Reitan, Citation1992) and sustained attention with the raw score on the concentration performance scale of the d2 test (Brickenkamp & Kraan, Citation2007). Memory was assessed using the delayed recall score of the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) for verbal memory (Saan & Deelman, Citation1986), the delayed recall score of the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test (ROCTF; Osterrieth, Citation1944) for visual memory, and the raw total score of the Digit Span of the WAIS-IV (Wechsler, Citation2008) for working memory. Executive functioning was assessed using two subtests of the Behavioral Assessment of the Dysexecutive Syndrome (BADS; Wilson et al., Citation1996): planning was assessed using the raw total score on the Zoo map subtest and mental flexibility was assessed using the raw total score on the Rule Shift subtest.

Demographic and clinical covariates

Age, sex, and educational level were obtained. Educational level was classified following Verhage (Citation1983) (Verhage 1–4; followed or finished primary school and/or lowest-level secondary education, Verhage 5; finished average-level secondary education, Verhage 6–7; finished high-level secondary education or university).

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as mean (M) ± standard deviation (SD) or frequency (N) and percentages (%). Normality of the distribution of continuous variables was examined visually and using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests. The distribution of the Digit Span task, RAVLT, d2, TMT-B, and both BADS subtests deviated from a normal distribution (p < .001 for the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests). Furthermore, the NEO-FFI and BVAQ scores were skewed and deviated from the normal distribution. Log-transformation did not result in a normal distribution; therefore, the original variables were used. Scores of the other cognitive tests were normally distributed. Therefore, we used Spearman’s correlation coefficients instead of Pearson’s to estimate the bivariate correlations between personality factors and test scores on the cognitive tests.

The associations of each personality traits with cognitive functioning were analyzed with correlation analyses using continuous variables. Bivariate correlations between personality (continuous NEO-FFI scores of all five domains) and alexithymia (continuous total score of the BVAQ) and cognitive functioning (continuous WAIS-IV, RAVLT, ROCFT, d2, TMT-B, and BADS scores) were obtained using Spearman’s correlations (ρ). Because of our small sample size, data were reported with and without multiple comparison corrections. Bonferroni correction on p values was used to correct for multiple comparisons.

The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 28) (IBM Corporation, Citation2019). The statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05 for all analyses.

Results

Descriptive statistics

shows the demographic characteristics of the sample. The majority of the sample (82.6%,n = 19) was female and the mean age was 41.5 (SD = 14.14) years. A total of 47.8% finished mid-level education, 39.0% low-level education, and 13.0% high level education. Furthermore, 10 participants (43.5%) were married, 6 (26.0%) were living together or had a partner, 5 (21.7%) were single, 1 (4.3%) patient was divorced/widower and 1 (4.3%) patient was living with his/her parents. With regards to FND phenotype, the majority of our patients displayed either look-alike epileptic seizures or faints (n = 9, 39.1%) or limb weakness/paralysis (n = 5, 21.7%).

Table 1. Demographic variables of a sample (N = 23) of patients with FND.

Association of the big five personality factors and alexithymia with cognitive functioning in patients with FND

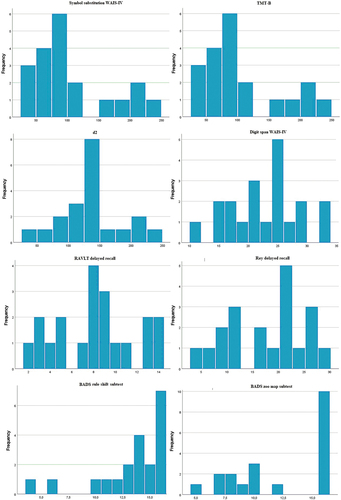

shows the distribution of scores on the NEO-FFI and BVAQ, and the raw scores on each neurocognitive test. shows the histograms for each neurocognitive test. shows the correlations between the Big Five personality factors, alexithymia and cognitive test scores.

Table 2. Distribution of personality, alexithymia, and cognitive test scores in a sample (N = 23) of patients with FND.

Table 3. Correlations between personality and alexithymia scores and cognitive scores in patients with FND (N = 23).

With regards to personality factors, higher scores of conscientiousness were associated with lower scores on planning (ρ = −0.52, p = .012). Other personality factors were not significantly correlated with cognitive functioning. Regarding alexithymia, higher scores of alexithymia were associated with lower scores on verbal memory (ρ= −0.46, p = .032) and with lower scores on sustained attention (ρ = −0.45, p = .046). Other neurocognitive test scores were not significantly correlated with alexithymia. The correlations did not remain significant after Bonferroni correction.

Discussion

In the current study, we examined the association between the Big Five personality factors (neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness), alexithymia, and cognitive functioning. Higher levels of conscientiousness were associated with lower test scores on planning, and higher levels of alexithymia were associated with lower scores on verbal memory and sustained attention; however, the associations were not significant after correction for multiple testing (Bonferroni correction). Other personality traits did not significantly correlate with cognitive test performance.

One previous study also investigated personality and cognition in FND, and reported that higher levels of neuroticism were associated with lower memory scores (Metternich et al., Citation2009). Likewise, neuroticism was associated with lower visual memory and planning scores in patients with somatic symptom and related disorders (Bartkowska et al., Citation2018; de Vroege et al., Citation2022). Our results did not find an association between neuroticism and cognitive functioning. Notably, there is a high variability of neuroticism levels amongst patients with FND, with different underlying psychopathology. As high neuroticism is frequently present amongst patients in FND (Perez et al., Citation2021), it remains pivotal to explore the extent to which neuroticism may play a role in (cognitive) symptomatology of FND.

Alexithymia and poorer executive functioning in a healthy population was reported by Santorelli and Ready (Citation2015). Our study is the first to explore alexithymia and cognitive functioning in patients with FND, where high alexithymia FND patients had lower test scores on verbal memory. Future studies should replicate the current findings in order to draw further conclusions about the role of alexithymia in FND and cognitive symptomatology.

Caution should be exercised while interpreting the results of our study. First, because of the small sample size due to the low prevalence rates of FND, the results of this study can best be seen as explorative or preliminary. We were underpowered to control for variables such as age, education level, and gender in the analyses. Particularly because our results did not remain significant after Bonferroni correction, replication studies are needed with larger samples of patients with FND. Second, given the cross-sectional design of the study, we cannot draw any causal conclusion on whether or not personality traits contribute to the development of cognitive symptoms over time. Third, our study depended on self-reported questionnaires assessing Big Five personality traits and alexithymia. Reliable self-reported symptoms depend on a certain degree of introspection and mentalization (Zunhammer et al., Citation2015) which is often impaired in this specific patient group. Lastly, when measuring cognitive functioning using neurocognitive tests, decisions regarding specific test materials have to be made. A different neurocognitive test selection might result in different results. We have selected our neurocognitive tests based on their extensive use in clinical practice and evidence of good psychometrics. Despite of these limitations, our study is the first to explore the link between personality traits and cognitive functioning in patients with FND and provides interesting starting points for future studies.

Future research should continue to focus on cognitive symptomatology in FND, in order to try to underpin the underlying mechanisms that cause cognitive problems within FND. One example is the role of depression and alexithymia in cognition in patients with FND, as alexithymia and depression are prevalent in patients with somatic symptom and related disorders (de Vroege et al., Citation2018a), and alexithymia and depression are highly associated (Honkalampi, Hintikka, Saarinen, et al., Citation2000; Honkalampi, Hintikka, Tanskanen, et al., Citation2000; Li et al., Citation2015). Some consider alexithymia a predictor of depression (Günther et al., Citation2016; Tolmunen et al., Citation2011) and others as a secondary reaction to depression (de Vente et al., Citation2006; Honkalampi, Hintikka, Saarinen, et al., Citation2000; Saarijärvi et al., Citation2001). Depression is characterized by poorer cognitive functioning (Rock et al., Citation2014), so the potential role of depression and alexithymia on cognition could be relevant in patients with FND. Lastly, the (possible) differences between subjective versus objective neurocognitive functioning and the role of personality/alexithymia in patients with FND is worthwhile exploring in the future.

From a neuropsychiatric/neurobiological point of view, the results of our preliminary study can also be interesting, specifically regarding the role of the left amygdala and the left hippocampus in FND. The left amygdala has been considered as a key substrate of alexithymia in several (neuroimaging) studies (Goerlich-Dobre, Lamm, et al., Citation2015; Goerlich-Dobre, Votinov, et al., Citation2015; Han et al., Citation2018; Xu et al., Citation2018), and may be part of a complex pattern in emotional awareness across a range of psychopathological conditions including FND (Goerlich-Dobre, Lamm, et al., Citation2015). Additionally, the hippocampus and amygdala are involved in association and memory processes (Madan et al., Citation2017) and episodic encoding (Killgore et al., Citation2000). The relationship between the left hippocampus (memory) and the left amygdala (alexithymia) could be a possible neural underpinning in patients with FND, but should be explored in future studies.

The cognitive symptomatology in FND patients may hamper treatment efficacy (e.g. L. B. Brown et al., Citation2014; de Vroege et al., Citation2021). Specialized treatment options are needed in order to treat cognitive symptoms in FND, such as treatment options developed in other fields of expertise (Fasotti et al., Citation2000; Winkens, van Heugten, Wade, & Fasotti, Citation2009; Winkens, van Heugten, Wade, Habets, et al., Citation2009). One case study explored efficacy of cognitive rehabilitation treatment in FND and the results were promising (de Vroege et al., Citation2017). The preliminary results of the current study could inspire future studies on the role of personality and alexithymia on treatment results.

To conclude, our study results suggest an association between personality traits and cognitive functioning in patients with FND. Specifically, high conscientiousness was associated with lower scores on planning, whereas higher alexithymia was associated with lower verbal memory and attentional scores. Future studies, with larger sample sizes and statistical power, are needed to further explore the role of personality traits in FND patients and cognitive symptomatology. Furthermore, underlying mechanisms should be explored, such as the role of depression with alexithymia on cognition. As cognitive symptomatology may be negatively related to psychological and psychotherapeutic treatment results, it is pivotal to further investigate the origin of cognitive symptomatology in FND, in order to create or adapt therapeutic treatment possibilities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). DSM-IV-TR: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, text revision.Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 75.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Pub.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). DSM-5-TR: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

- Bartkowska, W., Samborski, W., & Mojs, E. (2018). Cognitive functions, emotions and personality in woman with fibromyalgia. Anthropologischer Anzeiger, 75(4), 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1127/anthranz/2018/0900

- Bates, T. C., & Rock, A. (2004). Personality and information processing speed: Independent influences on intelligent performance. Intelligence, 32(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2003.08.002

- Bermond, B., Bierman, D. J., Cladder, M. A., Moormann, P. P., & Vorst, H. C. (2010). The cognitive and affective alexithymia dimensions in the regulation of sympathetic responses. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 75(3), 227–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2009.11.004

- Bermond, B., Vorst, H. C., & Moormann, P. P. (2006). Cognitive neuropsychology of alexithymia: Implications for personality typology. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 11(3), 332–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546800500368607

- Bodde, N. M., Bartelet, D. C., Ploegmakers, M., Lazeron, R. H., Aldenkamp, A. P., & Boon, P. A. (2011). MMPI-II personality profiles of patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy & Behavior, 20(4), 674–680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.01.034

- Bodde, N. M., Brooks, J. L., Baker, G. A., Boon, P. A. J. M., Hendriksen, J. G. M., Mulder, O. G., & Aldenkamp, A. P. (2009). Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures–definition, etiology, treatment and prognostic issues: A critical review. Seizure, 18(8), 543–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2009.06.006

- Brickenkamp, R., & Kraan, M. (2007). d2: Aandachts-en concentratietest: Handleiding. Hogrefe.

- Brown, R. J., Bouska, J. F., Frow, A., Kirkby, A., Baker, G. A., Kemp, S., & Reuber, M. (2013). Emotional dysregulation, alexithymia, and attachment in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy & Behavior: E&B, 29(1), 178–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.07.019

- Brown, L. B., Nicholson, T. R., Aybek, S., Kanaan, R. A., & David, A. S. (2014). Neuropsychological function and memory suppression in conversion disorder. Journal of Neuropsychology, 8(2), 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnp.12017

- Carson, A., Ludwig, L., & Welch, K. (2016). Psychologic theories in functional neurologic disorders. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 139, 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-801772-2.00010-2

- Carson, A., Stone, J., Hibberd, C., Murray, G., Duncan, R., Coleman, R., Warlow, C., Roberts, R., Pelosi, A., Cavangh, J., Matthews, K., Goldbeck, R., Hansen, C., & Sharpe, M. (2011). Disability, distress and unemployment in neurology outpatients with symptoms ‘unexplained by organic disease’. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 82(7), 810–813. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2010.220640

- Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1995). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor (NEO-FFI) inventory professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Curtis, R. G., Windsor, T. D., & Soubelet, A. (2015). The relationship between big-5 personality traits and cognitive ability in older adults - a review. Aging, Neuropsychology and Cognition, 22(1), 42–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825585.2014.888392

- Demartini, B., Petrochilos, P., Ricciardi, L., Price, G., Edwards, M. J., & Joyce, E. (2014). The role of alexithymia in the development of functional motor symptoms (conversion disorder). Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 85(10), 1132–1137. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2013-307203

- de Vente, W., Kamphuis, J. H., & Emmelkamp, P. M. (2006). Alexithymia, risk factor or consequence of work-related stress? Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics, 75(5), 304–311. https://doi.org/10.1159/000093953

- de Vroege, L., Emons, W. H. M., Sijtsma, K., & van der Feltz-Cornelis, C. M. (2018a). Alexithymia has No clinically relevant association with outcome of multimodal treatment tailored to needs of patients suffering from somatic symptom and related disorders. A clinical prospective study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 292. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00292

- de Vroege, L., Emons, W. H. M., Sijtsma, K., & van der Feltz-Cornelis, C. M. (2018b). Psychometric properties of the bermond-vorst alexithymia questionnaire (BVAQ) in the general population and a clinical population. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 111. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00111

- de Vroege, L., Khasho, D., Foruz, A., van der Feltz-Cornelis, C. M., & Walla, P. (2017). Cognitive rehabilitation treatment for mental slowness in conversion disorder: A case report. Cogent Psychology, 4(1), 1348328. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2017.1348328

- de Vroege, L., Koppenol, I., Kop, W. J., Riem, M. M. E., & van der Feltz-Cornelis, C. M. (2021). Neurocognitive functioning in patients with conversion disorder/functional neurological disorder. Journal of Neuropsychology, 15(1), 69–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnp.12206

- de Vroege, L., Timmermans, A., Kop, W. J., & van der Feltz-Cornelis, C. M. (2018). Neurocognitive dysfunctioning and the impact of comorbid depression and anxiety in patients with somatic symptom and related disorders: A cross-sectional clinical study. Psychological Medicine, 48(11), 1803–1813. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291717003300

- de Vroege, L., Woudstra de Jong, J. E., Videler, A. C., & Kop, W. J. (2022). Personality factors and cognitive functioning in patients with somatic symptom and related disorders. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 163, 111067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2022.111067

- Edwards, M. J., & Bhatia, K. P. (2012). Functional (psychogenic) movement disorders: Merging mind and brain. Lancet Neurology, 11(3), 250–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(11)70310-6

- Ekanayake, V., Kranick, S., LaFaver, K., Naz, A., Webb, A. F., LaFrance, W. C., Jr., Hallet, M., & Voon, V. (2017). Personality traits in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) and psychogenic movement disorder (PMD): Neuroticism and perfectionism. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 97, 23–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.03.018

- Eysenck, M. W. (1974). Extraversion, arousal, and retrieval from semantic memory. Journal of Personality, 42(2), 319–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1974.tb00677.x

- Fasotti, L., Kovacs, F., Eling, P. A. T. M., & Brouwer, W. H. (2000). Time pressure management as a compensatory strategy training after closed head injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation: An International Journal, 10(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/096020100389291

- Goerlich-Dobre, K. S., Lamm, C., Pripfl, J., Habel, U., & Votinov, M. (2015). The left amygdala: A shared substrate of alexithymia and empathy. Neuroimage, 122, 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.08.014

- Goerlich-Dobre, K. S., Votinov, M., Habel, U., Pripfl, J., & Lamm, C. (2015). Neuroanatomical profiles of alexithymia dimensions and subtypes. Human Brain Mapping, 36(10), 3805–3818. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.22879

- Günther, V., Rufer, M., Kersting, A., & Suslow, T. (2016). Predicting symptoms in major depression after inpatient treatment: The role of alexithymia. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 70(5), 392–398. https://doi.org/10.3109/08039488.2016.1146796

- Hallet, M., Aybek, S., Dworetzky, B. A., McWhirter, L., Staab, J. P., & Stone, J. (2022). Functional neurological disorder: New subtypes and shared mechanisms. Lancet Neurology, 21(6), 537–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00422-1

- Han, D., Li, M., Mei, M., & Sun, X. (2018). The functional and structural characteristics of the emotion network in alexithymia. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 14, 991–998. https://doi.org/10.2147/ndt.s154601

- Honkalampi, K., Hintikka, J., Saarinen, P., Lehtonen, J., & Viinamäki, H. (2000). Is alexithymia a permanent feature in depressed patients? Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics, 69(6), 303–308. https://doi.org/10.1159/000012412

- Honkalampi, K., Hintikka, J., Tanskanen, A., Lehtonen, J., & Viinamäki, H. (2000). Depression is strongly associated with alexithymia in the general population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 48(1), 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(99)00083-5

- Hughes, D. J., Kratsiotis, I. K., Niven, K., & Holman, D. (2020). Personality traits and emotion regulation: A targeted review and recommendation. Emotion, 20(1), 63–67. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000644

- IBM Corp. (2021). IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 28.0. IBM Corp.

- Inamura, K., Shinagawa, S., Nagata, T., Tagai, K., Nukariya, K., & Nakayama, K. (2015). Cognitive dysfunction in patients with late-life somatic symptom disorder: A comparison according to disease severity. Psychosomatics, 56(5), 486–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2014.10.004

- Jalilianhasanpour, R., Williams, B., Gilman, I., Burke, M. J., Glass, S., Fricchione, G. L., Keshavan, M. S., LaFrance, W. C., & Perez, D. L. (2018). Resilience linked to personality dimensions, alexithymia and affective symptoms in motor functional neurological disorders. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 107, 55–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.02.005

- John, O. P., & Srivasstava, S. (1999). The big five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 102–138). GuilfordPress.

- Jungilligens, J., Paredes-Echeverri, S., Popkirov, S., Barrett, L. F., & Perez, D. L. (2022). A new science of emotion: Implications for functional neurological disorder. Brain, 145(8), 2648–2663. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awac204

- Kaplan, M. J., Dwivedi, A. K., Privitera, M. D., Isaacs, K., Hughes, C., & Bowman, M. (2013). Comparisons of childhood trauma, alexithymia, and defensive styles in patients with psychogenic non-epileptic seizures vs. epilepsy: Implications for the etiology of conversion disorder. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 75(2), 142–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.06.005

- Kellner, R. (1990). Somatization: Theories and research. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 178(3), 150–160. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199003000-00002

- Killgore, W. D. S., Casasanto, D. J., Yurgelun-Todd, D. A., Maldjian, J. A., & Detre, J. A. (2000). Functional activation of the left amygdala and hippocampus during associative encoding. Neuroreport, 11(10), 2259–2263. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001756-200007140-00039

- Koelen, J. A., Eurelings-Bontekoe, E. H., Stuke, F., & Luyten, P. (2015). Insecure attachment strategies are associated with cognitive alexithymia in patients with severe somatoform disorder. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 49(4), 264–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091217415589303

- Langguth, B., Kleinjung, T., Fischer, B., Hajak, G., Eichhammer, P., & Sand, P. G. (2007). Tinnitus severity, depression, and the big five personality traits. Progress in Brain Research, 166, 221–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0079-6123(07)66020-8

- Li, S., Zhang, B., Guo, Y., & Zhang, J. (2015). The association between alexithymia as assessed by the 20-item Toronto alexithymia scale and depression: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 227(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.02.006

- Madan, C. R., Fujiwara, E., Caplan, J. B., & Sommer, T. (2017). Emotional arousal impairs association-memory: Roles of amygdala and hippocampus. Neuroimage, 156, 14–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.04.065

- McWhirter, L., Ritchie, C., Stone, J., & Carson, A. (2020). Functional cognitive disorders: A systematic review. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(2), 191–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(19)30405-5

- Menon, V., Shanmuganathan, B., Thamizh, J. S., Arun, A. B., Kuppili, P. P., & Sarkar, S. (2018). Personality traits such as neuroticism and disability predict psychological distress in medically unexplained symptoms: A three-year experience from a single centre. Personality and Mental Health, 12(2), 145–154. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmh.1405

- Metternich, B., Schmidtke, K., & Hüll, M. (2009). How are memory complaints in functional memory disorder related to measures of affect, metamemory and cognition? Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 66(5), 435–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.07.005

- Morsy, S. K., Aybek, S., Carson, A., Nicholson, T. R., Stone, J., Kamal, A. M., Abdel-Fadeel, N. A., Hassan, M. A., & Kanaan, R. A. A. (2022). The relationship between types of life events and the onset of functional neurological (conversion) disorders in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 52(3), 401–418. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721004669

- Mostafaei, S., Kabir, K., Kazemnejad, A., Feizi, A., Mansourian, M., Hassanzadeh Keshteli, A., Afshar, H., Arzaghi, S. M., Dehkordi, S. R., Adibi, P., & Ghadirian, F. (2019). Explanation of somatic symptoms by mental health and personality traits: Application of Bayesian regularized quantile regression in a large population study. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 207. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2189-1

- Murdock, K. W., Oddi, K. B., & Bridgett, D. J. (2013). Cognitive correlates of personality: Links between executive functioning and the big five personality traits. Journal of Individual Differences, 34(2), 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001/a000104

- Nemiah, J. C., & Sifneos, P. E. (1970). Psychosomatic illness: A problem in communication. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics, 18(1–6), 154–160. https://doi.org/10.1159/000286074

- Osterrieth, P. A. (1944). Filetest de copie d’une figure complex: Contribution a l’etude de la perception et de la memoire [The test of copying a complex figure: A contribution to the study of perception and memory]. Archives de psychologie, 30(119), 286–356.

- Paine, P., Kishor, J., Worthen, S. F., Gregory, L. J., & Aziz, Q. (2009). Exploring relationships for visceral and somatic pain with autonomic control and personality. Pain, 144(3), 236–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2009.02.022

- Perez, D. L., Aybek, S., Popkirov, S., Kozlowska, K., Stephen, C. D., Anderson, J., Shura, R., Ducharme, S., Carson, A., Hallett, M., Nicholson, T. R., Stone, J., LaFranse, W. Jr., & Voon, V. (2021). A review and expert opinion on the Neuropsychiatric assessment of motor functional neurological disorders. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 33(1), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.19120357

- Perez, D. L., Barsky, A. J., Vago, D. R., Baslet, G., & Silbersweig, D. A. (2015). A neural circuit framework for somatosensory amplification in somatoform disorders. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 27(1), e40–50. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.13070170

- Reitan, R. M. (1992). Trail making test: Manual for administration and scoring. Reitan Neuropsychology Laboratory.

- Reuber, M., Howlett, S., Khan, A., & Grünewald, R. A. (2007). Non-epileptic seizures and other functional neurological symptoms: Predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors. Psychosomatics, 48(3), 230–238. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psy.48.3.230

- Rief, W., & Broadbent, E. (2007). Explaining medically unexplained symptoms-models and mechanisms. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(7), 821–841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.005

- Rock, P., Roiser, J., Riedel, W., & Blackwell, A. (2014). Cognitive impairment in depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 44(10), 2029–2040. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291713002535

- Saan, R. J., & Deelman, B. G. (1986). De 15 Woordentaak A en B [15 Words task]. Department of Neuropsychology, Academic Hospital Groningen.

- Saarijärvi, S., Salminen, J. K., & Toikka, T. B. (2001). Alexithymia and depression: A 1-year follow-up study in outpatients with major depression. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 51(6), 729–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00257-4

- Santorelli, G. D., & Ready, R. E. (2015). Alexithymia and executive function in younger and older adults. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 29(7), 938–955. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2015.1123296

- Schmand, B., & Lindeboom, J. (2005). The Amsterdam short-term memory test. PITS Leiden.

- Sifneos, P. E. (1973). The prevalence of ‘alexithymic’characteristics in psychosomatic patients. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics, 22(2–6), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.1159/000286529

- Stone, J., Warlow, C., Deary, I., & Sharpe, M. (2020). Predisposing risk factors for functional limb weakness: A case-control study. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 32(1), 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.19050109

- Sutin, A. R., Stephan, Y., Luchetti, M., & Terracciano, A. (2019). Five-factor model personality traits and cognitive function in five domains in older adulthood. BMC Geriatrics, 19(1), 343. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1362-1

- Taylor, G. J., Bagby, R. M., & Parker, J. D. (1999). Disorders of affect regulation: Alexithymia in medical and psychiatric illness. Cambridge University Press.

- Testa, S. M., Schefft, B. K., Szaflarski, J. P., Yeh, H. S., & Privitera, M. D. (2007). Mood, personality, and health-related quality of life in epileptic and psychogenic seizure disorders. Epilepsia, 48(5), 973–982. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00965.x

- Tolmunen, T., Heliste, M., Lehto, S. M., Hintikka, J., Honkalampi, K., & Kauhanen, J. (2011). Stability of alexithymia in the general population: An 11-year follow-up. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 52(5), 536–541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.09.007

- Tombaugh, T. M. (1996). TOMM test of memory malingering: Manual. Multi Health Systems.

- Tomić, A., Petrović, I., Pešić, D., Vončina, M. M., Svetel, M., Mišković, N. D., Potrebić, A., Toševski, D. L., & Kostić, V. S. (2017). Is there a specific psychiatric background or personality profile in functional dystonia? Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 97, 58–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.04.004

- Verhage, F. (1983). Intelligence and age: Study with Dutch people aged 12-77. Van Gorcum.

- Vorst, H. C., & Bermond, B. (2001). Validity and reliability of the bermond–vorst alexithymia questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences, 30(3), 413–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00033-7

- Waller, E., & Scheidt, C. E. (2006). Somatoform disorders as disorders of affect regulation: A development perspective. International Review of Psychiatry, 18(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540260500466774

- Wechsler, D. (2008). Wechsler adult intelligence scale (WAIS-IV) (4th ed.). NCS Pearson.

- Williams, P. G., Suchy, Y., & Kraybill, M. L. (2010). Five-factor model personality traits and executive functioning among older adults. Journal of Research in Personality, 44(4), 485–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2010.06.002

- Williams, M. K., Waite, L., van Wyngaarden, J. J., Meyer, A. R., & Koppenhaver, S. L. (2023). Beyond yellow flags: The big-five personality traits and psychologically informed musculoskeletal rehabilitation. Musculoskeletal Care, 21(4), 1161–1174. https://doi.org/10.1002/msc.1797

- Willment, K., Hill, M., Baslet, G., & Loring, D. W. (2015). Cognitive impairment and evaluation in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: An integrated cognitive-emotional approach. Clinical EEG and Neuroscience, 46(1), 42–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1550059414566881

- Wilson, B. A., Alderman, N., Burgess, P. W., Emslie, H., & Evans, J. J. (1996). Behavioural assessment of the dysexecutive syndrome. Thames Valley Test Company.

- Winkens, I., van Heugten, C. M., Wade, D. T., & Fasotti, L. (2009). Training patients in time pressure management, a cognitive strategy for mental slowness. Clinical Rehabilitation, 23(1), 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215508097855

- Winkens, I., van Heugten, C. M., Wade, D. T., Habets, E. J., & Fasotti, I. L. (2009). Efficacy of time pressure management in stroke patients with slowed information processing: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 90(10), 1672–1679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2009.04.016

- Xu, P., Opmeer, E. M., van Tol, M. J., Goerlich, K. S., & Aleman, A. (2018). Structure of the alexithymic brain: A parametric coordinate-based meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 87, 50–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.01.004

- Zunhammer, M., Halski, A., Eichhammer, P., & Busch, V. (2015). Theory of mind and emotional awareness in chronic somatoform pain patients. Public Library of Science ONE, 10(10), e0140016. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0140016