Abstract

Background

Task shifting from general practitioners (GPs) to other health professionals could solve the increased workload, but an overview of the evidence is lacking for out-of-hours primary care (OOH-PC).

Objectives

To evaluate the content and quality of task shifting from GPs to other health professionals in clinic consultations and home visits in OOH-PC.

Methods

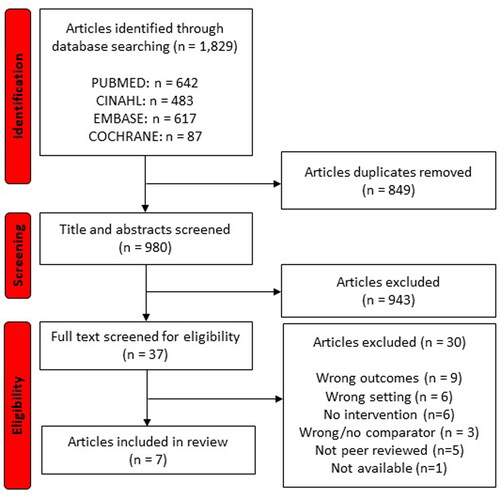

Four database literature searches were performed on 13 December 2021, and updated in August 2023. We included articles that studied content (patient characteristics, reason for encounter) and/or quality (patient satisfaction, safety, efficiency) of task shifting in face-to-face contacts at OOH-PC. Two authors independently screened articles for inclusion and assessed the methodological quality of included articles using the JBI critical appraisal checklist. Data was extracted and results were synthesised in a narrative summary.

Results

The search identified 1,829 articles, resulting in the final inclusion of seven articles conducted in the UK or the Netherlands. Studies compared GPs with other health professionals (mainly nurses). These other health professionals saw patients with less urgent health problems, younger patients, and patients with less complex health problems than GPs. Most studies concluded that other health professionals provided safe and vastly efficient care corresponding to the level of GPs but findings about productivity were inconclusive.

Conclusion

The level of safety and efficiency of care provided by other health professionals in OOH-PC seems like that of GPs, although they mainly see patients presenting with less urgent and less complex health problems.

KEY MESSAGES

Task shifting from general practitioners to other health professionals could increase treatment capacity in out-of-hours primary care.

Task shifting occurs for care to patients with less urgent and less complex health issues.

The long-term implications of task shifting in out-of-hours primary care should be investigated.

Introduction

Primary care is currently facing high demands. This is caused by multiple factors, including an ageing population, higher levels of multimorbidity and improved treatment options [Citation1, Citation2]. Moreover, organisational changes, such as transfer of tasks from secondary to primary care and shorter hospital stays, have increased the pressure on both daytime primary care and out-of-hours primary care (OOH-PC) [Citation3, Citation4]. In addition, the growing demand in the population for 24-hour health services contributes to higher utilisation of OOH services [Citation5].

In many Western countries, general practice plays a vital role in proving OOH-PC, although organisational models vary [Citation5]. The increased pressure combined with workforce shortage among general practitioners (GPs) challenges the provision of OOH-PC [Citation4]. Identifying a model that ensures accessibility, quality and efficiency in OOH-PC is not an easy task. One such model could be task shifting from GPs to other health professionals (e.g. nurses, physician assistants and paramedics), including consultations with patients having non-urgent and non-complex reasons for encounter. Task shifting could increase treatment capacity, thereby improving health services, maintaining high-quality standards and increasing the availability of care [Citation6, Citation7].

In daytime general practice, task shifting from GPs to nurses is a feasible healthcare model that provides safe care of good quality and with high patient satisfaction [Citation2]. However, this evidence from daytime care cannot be generalised to OOH-PC. Compared with daytime general practice, OOH-PC deals with more acute patient complaints, the health professionals do not have prior knowledge about the patient, and they differ in every shift [Citation8].

In OOH-PC, task shifting to other health professionals is largely restricted to telephone triage, which is known to be safe and efficient [Citation9–11]. Task shifting in clinic consultations and home visits is limited and evidence of the implications is scarce [Citation12, Citation13]. A systematic review of six qualitative studies on task shifting in OOH-PC highlighted the importance of defining a clear scope of practice and building confidence in other health professionals through appropriate training, support and mentoring [Citation12]. However, this review did not study quantitative aspects of the quality of care provided by other health professionals, for example efficiency and safety. Thus, we aimed to evaluate the content and quality of task shifting from GPs to other health professionals in clinic consultations and home visits in OOH-PC.

Methods

Design

We conducted a systematic literature review, following the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement (Supplemental material Tables 1 and 2) [Citation14]. The protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) before initiation of the study (registration no: 301974).

Literature search

The search was conducted on 13 December 2021, and updated in August 2023. We systematically searched the following databases: PubMed/Medline, the Cochrane Library, Embase and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). We made an electronic search for each database in collaboration with an experienced librarian. Search terms covered terms for OOH-PC (Practitioner Cooperative, Out of Hours, After Hours Care), health professionals (Paramedic, Physician Assistant, Emergency Medical Technicians, Non-Medical Practitioner, Nurse, Student) and task shifting (Shifting, Delegation, Substitution). Outcome measures were not included in the search but were part of the subsequent screening of articles. The full database search protocol is available in Supplemental material Table 3.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible studies had to focus on OOH-PC, and either address content or quality of task shifting. Study inclusion met the Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcomes (PICO) criteria (Box 1). No restrictions were placed on publication date, study design or country. We included only original research manuscripts in English.

Box 1. PICO criteria used in the literature search.

Study selection

Articles were screened for eligibility with the software platform Covidence [Citation15]. Two authors (KB and MN) initially screened all titles and abstracts independently based on the above-mentioned PICO criteria. The same two authors reviewed articles included for full-text screening. In disagreement, a third author (LH) was consulted, and consensus was obtained before inclusion. The reference lists in the included articles were screened manually by one author (KB) to identify additional eligible material.

Assessment of study quality

Two reviewers (KB and MN) independently assessed the included articles quality. Any disagreements between reviewers were discussed and resolved by consensus. In accordance with the study designs of the included articles, we used the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Quasi-experimental Studies [Citation16]. This approach was not taken to weight findings or exclude studies but to highlight potential bias in the results reported in the included articles.

Extraction and synthesis of data

Extracted data included first author, country, publication year, study design, setting, number of patients, intervention group and control group. Data was extracted according to the two main outcomes: content (patient characteristics, reason for encounter) and quality (patient satisfaction, safety, efficiency (e.g. consultation length, prescription, test, investigations, referrals, admission and return consultations)). Quality dimensions were based on relevant frameworks [Citation17, Citation18], focusing on pertinent dimensions to quantitative research that were not addressed in an existing literature review of qualitative studies. A meta-analysis of the included articles was not deemed appropriate due to the heterogeneous outcome measures. Therefore, we synthesised the results in a narrative summary according to the main outcome measures. We focused on statistically significant findings, as presented by the original articles.

Results

Literature search

The literature search resulted in 1,829 articles for screening (). After removal of duplicates and screening of title and abstract, 37 articles were selected for full-text screening. After exclusion, seven articles remained for data extraction and synthesis [Citation8, Citation19–24]. These seven articles were based on five studies.

Characteristics of included articles

An overview of the included articles is presented in . All seven studies were non-randomised studies from the United Kingdom (n = 3) or the Netherlands (n = 4), which had been published between 2010 and 2019 [Citation8, Citation19–24]. The studies had been conducted in large-scale OOH-PC services called general practitioner cooperatives (GPCs). Five articles investigated task shifting in-clinic consultations [Citation8, Citation19–22], whereas two investigated task shifting in-home visits [Citation23, Citation24]. The intervention groups consisted of nurse practitioners (NPs), advanced nurse practitioners (ANPs) or emergency care practitioners (ECPs). NPs and ANPs had completed a two-year master’s programme. An NP and ANP could independently initiate and perform selected procedures (e.g. prescribing medication) using the same guidelines as GPs [Citation8, Citation19, Citation20, Citation23, Citation24]. ECPs had a paramedic or nursing background and had completed additional education in history taking; physical examination and diagnostic tests, and they could administer and supply medication under certain conditions [Citation21, Citation22]. This article will refer to NPs, ANPs and ECPs jointly as ‘other health professionals`. In all seven included articles, other health professionals worked independently but could consult a GP at any time (face-to-face in-clinic consultations and by telephone during home visits).

Table 1. Overview of main characteristics of the included articles.

Risk of bias within studies

shows the risk of bias assessment for the studies, using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Quasi-Experimental Studies [Citation16]. Six studies had a quality score of 6/9, whereas one study scored 3/9. Most studies lacked similarity in participants in the compared groups, pre- and post-measurement and follow up.

Table 2. Risk of bias summary.

Content: Patient characteristics and reasons for encounter

Five articles reported that other health professionals could only see a predefined patient population; this often excluded patients with complex health problems () [Citation8, Citation19, Citation20, Citation23, Citation24]. Other health professionals handled patients with less urgent health problems [Citation19, Citation24], younger patients, and patients with less complex health problems (e.g. traumas and skin problems) [Citation19–24] compared with GPs.

Table 3. Description of content in the included articles.

Quality: Patient satisfaction

Smits et al. found that patients assessed the care provided by other health professionals in-home visits significantly higher (grade 8.6) than care by GPs (grade 8.3). This difference in favour of other health professionals was significant for the following aspects of satisfaction: confidence in expertise of care provider, usefulness of advice, information on safety netting and interest in personal situations [Citation24]. Collins identified four patient complaints that were seen within 12-months after home visits performed by other health professionals; these concerned management of care and communication [Citation23].

Quality: Safety

In Smit et al. two GPs assessed adherence to protocols (based on the national GP guidelines) and reasoned deviation for home visits. They found that other health professionals more often adhered to protocol than GPs (NPs 84.9%; GPs 76.2%). Deviations from the protocol seemed more appropriate among GPs (NPs 2.0%; GPs 5.7%), whereas unreasoned deviation could harm the patient (NPs 13.1%; GPs 18.1%). A follow-up review of patient records by the patient’s own GP did not identify significant differences between both groups in terms of frequency of missed diagnoses, complications, and follow-up contacts [Citation24].

Collins found that other health professionals provided more consistent and slightly better documentation of home visits than GPs. The response time of other health professionals aligned with that of the GPs, except for immediate one-hour response time (met goals: ANPs 34%; GPs 75%) [Citation23].

Quality: Efficiency

Productivity

Van der Biezen et al. (2016, 2017) found a lower mean number of clinic consultations per hour for other health professionals than for GPs, regardless of the team setup [Citation8, Citation20]. Smits et al. found similar results; NPs had significantly longer home visits compared to GPs (NPs 34.1 mins; GPs 21.1 mins) [Citation24]. In contrast, Mason et al., O’Keeffe et al. and Collins found that other health professionals had shorter clinic consultations and home visits compared with GPs [Citation21–23]. Furthermore, van der Biezen et al. (2017) found that other health professionals completed most of their consultations autonomously without consulting a GP (≥ 93%) [Citation20]. Smits et al. also found that NPs needed remote GP consultation in 21.5% of home visits (21.5%) [Citation24].

Diagnostic tests

Van der Biezen et al. (2016) found no significant difference between NPs and GPs regarding referrals to X-ray (NPs 5.6%; GPs 4.2%) [Citation8]. Mason et al. and O’Keeffe et al. found that other health professionals ordered more diagnostic tests (e.g. electrocardiograph, radiology, urine and laboratory tests) after consultations compared with GPs [Citation21, Citation22].

Prescriptions

For clinic consultations, Van der Biezen et al. (2016) and Smits et al. found that other health professionals prescribed significantly fewer drugs compared with GPs (Van der Biezen et al.: NPs 37.1%; GPs 43% and Smits et al.: NPs 19.9%; GPs 30.6%) [Citation8, Citation24]. ÓKeeffe et al. also found that other health professionals less often than GPs administered and supplied medications to patients (ECPs 45.1%; GPs 54.9%) [Citation22], whereas Mason et al. did not find differences between the two groups in administration and supply of medications [Citation21]. For home visits, Collins found that other health professionals and GPs had comparable prescription rates for similar prescription types [Citation23]. Smits et al. reported that the patient’s own GP significantly more often assessed medication prescriptions by other health professionals as appropriate than by GPs (NPs 93.7%; GPs 79.5%) [Citation24].

Referrals

Van der Biezen et al. (2016) found that clinic consultations conducted by other health professionals resulted in significantly fewer referrals to the emergency department (ED) than consultations by GPs (NPs 5.1%; GPs 11.3%) [Citation8]. However, Mason et al. and ÓKeeffe et al. found a higher hospital referral rate by other health professionals compared with GPs (ECPs 17.1%; GPs 10.7% and ECPs 12.8%; GPs 9.3%) [Citation21, Citation22]. For home visits, Collins found that other health professionals seemed to refer fewer patients to a hospital after a home visit compared with GPs (ANPs 12.9%; GPs 16.3%) [Citation23]. In contrast, Smits et al. found that other health professionals significantly more often referred patients to the hospital after a home visit than GPs (NPs 24.1%; GPs 15.9%) () [Citation24].

Table 4. Efficiency of healthcare provided by other healthcare professionals compared to regular care by GPs.

Discussion

Main findings

This review evaluated the content and quality of task shifting from GPs to other health professionals in face-to-face clinic consultations and home visits in OOH-PC setting. Other health professionals handled patients with less urgent health problems, younger patients, and patients with less complex health problems than GPs. Most studies concluded that other health professionals provided equally safe and efficient care as GPs. Other health professionals seemed to order more diagnostic tests and have fewer prescriptions than GPs. However, results about productivity and referral rates of other health professionals compared with GPs were inconclusive.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this systematic literature review is the first to evaluate the content and quality of task shifting in an OOH-PC setting. A significant strength is the detailed literature search in four comprehensive electronic databases.

Only seven articles were eligible for inclusion, which reflects the lack of evidence on task shifting in OOH-PC and highlights the need for more research. Moreover, only four research teams were involved, as one Dutch team published three articles and one research team published two articles from the UK. This highlights the clustering of this research. Although the organisation of OOH-PC varies across countries, the included articles all focused on task shifting in large-scale GPCs in two high-income European countries with a GP gatekeeping system. Therefore, these results can only be generalised to other countries with a similar OOH-PC system [Citation5, Citation25]. In addition, the included articles were heterogeneous, so a meta-analysis was not possible. Furthermore, the intervention groups consisted mainly of nurses with extensive experience and additional training, which may not apply directly to other countries, as additional nursing training programs are not standard in all countries. Finally, the predefined scope for other health professionals caused differences between the patient population seen by other health professionals and those seen by GPs. Consequently, the results on quality of care could be biased due to confounding by indication. This should be considered when interpreting the results.

Comparison with existing literature

We found that other health professionals handled patients with less urgent health problems, younger patients, and patients with less complex health problems than GPs. This difference in patient populations was mainly due to the predefined scope of care for other health professionals, which should be considered when interpreting the findings in relation to quality of care. In theory, more than 75% of the patients seeking OOH-PC present with health problems that would fall within the scope of the competence of other health professionals [Citation19, Citation20]. A study on task shifting in six countries indicated that NPs could provide 67–93% of all primary care services in the daytime [Citation26]. Many European countries face high demands for OOH-PC, with frequent contacts for non-urgent and non-complex health issues [Citation27]. Apart from task shifting, other solutions to the high demand for OOH-PC and the lack of GPs could also be strengthening daytime primary care and supporting citizens in their help-seeking [Citation4].

Most studies in this review concluded that other health professionals provided equally safe and efficient care as GPs in face-to-face clinic consultations and home visits in OOH-PC setting. No previous review evaluated the safety and efficiency of task shifting from GPs to other health professionals in this setting. However, task shifting from GPs to other health professionals appears to be equally feasible in an OOH-PC setting as in daytime general practice and could extend the workforce in OOH-PC [Citation1, Citation2, Citation6, Citation7, Citation28]. Results about productivity and referral rates were inconclusive, which could be due to different contexts and patient scope. In a review of daytime general practice, other health professionals had a lower productivity than GPs [Citation6]. Productivity may be even lower for other health professionals compared to GPs when considering the types of patients treated; other health professionals saw patients with less urgent health problems, younger patients, and patients with less complex health problems than GPs.

Most literature within the field of task shifting from GPs to other health professional’s in-clinic consultations and home visits in OOH-PC settings are qualitative studies [Citation12, Citation13, Citation29–35]. Two qualitative studies performed interviews of health professionals and stakeholders, finding that other health professionals may have the potential to make a substantial contribution to OOH-PC [Citation12, Citation33]. It is challenging to successfully implement new interventions, such as task shifting [Citation36–38]. Therefore, a clear definition of the scope of practice and role of other health professionals is important [Citation12, Citation32]. Furthermore, health professionals and patients must accept and support the new roles of both GPs and other health professionals [Citation32, Citation34, Citation35].

Implications for practice and future research

Based on the evidence on the content and quality of care of distributing tasks from GPs to other health professionals, task shifting might be relevant in alleviating the growing workload in OOH-PC. Task shifting seems to potentially reduce the demand for GP involvement in OOH-PC without significantly compromising quality. However, the effect on GP workload remains unclear due to the substantial confounding introduced by differences in patient scope (including urgency and complexity) and inconclusive findings on productivity. Further research is needed to investigate this, ensuring that both study groups have the same patient scope to avoid confounding by indication. When performing future research, it is crucial to clearly define the scope of practice for task shifting and the role of other health professionals to ensure successful implementation [Citation12, Citation32]. In addition, health professionals with different backgrounds should be included, such as medical students, paramedics and nurses, without additional training.

Conclusion

The safety and efficiency of care provided by other health professionals in OOH-PC seems similar to that of GPs, although they mainly see patients presenting with less urgent and less complex health problems.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the study design, drafting and revising of the manuscript and agreed to the final submitted version according to the recommendations of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. KB, MN and LH conducted the literature search and data extraction process.

| Abbreviations | ||

| ANP: | = | advanced nurse practitioner |

| C: | = | control |

| ECP: | = | emergency care practitioner |

| GP: | = | general practitioner |

| I: | = | intervention |

| MANP: | = | master’s degree in advanced nursing practice’ |

| N: | = | number |

| NP: | = | nurse practitioners |

| PICO: | = | Population, intervention, comparison and outcomes |

| PRISMA: | = | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis |

| PROSPERO: | = | Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| ROBINS-I: | = | Risk of Bias in Non-randomised Studies of Interventions |

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (48.8 KB)Availability of data and materials

The data used during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Leong SL, Teoh SL, Fun WH, et al. Task shifting in primary care to tackle healthcare worker shortages: an umbrella review. Eur J Gen Pract. 2021;27(1):198–210. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2021.1954616.

- Laurant M, van der Biezen M, Wijers N, et al. Nurses as substitutes for doctors in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7(7):Cd001271.

- Smits M, Rutten M, Keizer E, et al. The development and performance of after-hours primary care in The Netherlands: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(10):737–742. doi: 10.7326/M16-2776.

- Foster H, Moffat KR, Burns N, et al. What do we know about demand, use and outcomes in primary care out-of-hours services? A systematic scoping review of international literature. BMJ Open. 2020;10(1):e033481. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033481.

- Steeman L, Uijen M, Plat E, et al. Out-of-hours primary care in 26 european countries: an overview of organizational models. Fam Pract. 2020;37(6):744–750. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmaa064.

- Horrocks S, Anderson E, Salisbury C. Systematic review of whether nurse practitioners working in primary care can provide equivalent care to doctors. BMJ. 2002;324(7341):819–823. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7341.819.

- Martínez-González NA, Djalali S, Tandjung R, et al. Substitution of physicians by nurses in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):214. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-214.

- Van Der Biezen M, Adang E, Van Der Burgt R, et al. The impact of substituting general practitioners with nurse practitioners on resource use, production and health-care costs during out-of-hours: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(1):132. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0528-6.

- Lake R, Georgiou A, Li J, et al. The quality, safety and governance of telephone triage and advice services – an overview of evidence from systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):614. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2564-x.

- Huibers L, Smits M, Renaud V, et al. Safety of telephone triage in out-of-hours care: a systematic review. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2011;29(4):198–209. doi: 10.3109/02813432.2011.629150.

- Graversen DS, Christensen MB, Pedersen AF, et al. Safety, efficiency and health-related quality of telephone triage conducted by general practitioners, nurses, or physicians in out-of-hours primary care: a quasi-experimental study using the Assessment of Quality in Telephone Triage (AQTT) to assess audio-recorded telephone calls. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21(1):84. doi: 10.1186/s12875-020-01122-z.

- Lyness E, Parker J, Willcox ML, et al. Experiences of out-of-hours task-shifting from GPs: a systematic review of qualitative studies. BJGP Open. 2021;5(4):BJGPO.2021.0043. doi: 10.3399/BJGPO.2021.0043.

- Yuill J. The role and experiences of advanced nurse practitioners working in out of hours urgent care services in a primary care setting. Nurs Manag (Harrow). 2018;25(2):18–23. doi: 10.7748/nm.2018.e1745.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2021;74(9):790–799. doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2021.06.016.

- Covidence. [cited 2024 May 1]. Available from: Covidence.org

- Institute JB. JBI’s critical checklist for quasi-experimental studies. [cited 2024 May 1]. Available from: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools

- Hanefeld J, Powell-Jackson T, Balabanova D. Understanding and measuring quality of care: dealing with complexity. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(5):368–374. doi: 10.2471/BLT.16.179309.

- Campbell SM, Roland MO, Buetow SA. Defining quality of care. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(11):1611–1625. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00057-5.

- van der Biezen M, Schoonhoven L, Wijers N, et al. Substitution of general practitioners by nurse practitioners in out-of-hours primary care: a quasi-experimental study. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(8):1813–1824. doi: 10.1111/jan.12954.

- van der Biezen M, Wensing M, van der Burgt R, et al. Towards an optimal composition of general practitioners and nurse practitioners in out-of-hours primary care teams: a quasi-experimental study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(5):e015509. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015509.

- Mason S, O’Keeffe C, Knowles E, et al. A pragmatic quasi-experimental multi-site community intervention trial evaluating the impact of emergency care practitioners in different UK health settings on patient pathways (NEECaP trial). Emerg Med J. 2012;29(1):47–53. doi: 10.1136/emj.2010.103572.

- O’Keeffe C, Mason S, Bradburn M, et al. A community intervention trial to evaluate emergency care practitioners in the management of children. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(7):658–663. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.201889.

- Collins D. Assessing the effectiveness of advanced nurse practitioners undertaking home visits in an out of hours urgent primary care service in England. J Nurs Manag. 2019;27(2):450–458. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12680.

- Smits M, Peters Y, Ranke S, et al. Substitution of general practitioners by nurse practitioners in out-of-hours primary care home visits: a quasi-experimental study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;104:103445. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103445.

- Huibers L, Giesen P, Wensing M, et al. Out-of-hours care in western countries: assessment of different organizational models. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9(1):105. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-105.

- Maier CB, Barnes H, Aiken LH, et al. Descriptive, cross-country analysis of the nurse practitioner workforce in six countries: size, growth, physician substitution potential. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9):e011901. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011901.

- Huibers LA, Moth G, Bondevik GT, et al. Diagnostic scope in out-of-hours primary care services in eight European countries: an observational study. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12(1):30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-30.

- Swan M, Ferguson S, Chang A, et al. Quality of primary care by advanced practice nurses: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2015;27(5):396–404. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzv054.

- van der Biezen M, Wensing M, Poghosyan L, et al. Collaboration in teams with nurse practitioners and general practitioners during out-of-hours and implications for patient care; a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):589. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2548-x.

- Moule P, Clompus S, Lockyer L, et al. Preparing non-medical clinicians to deliver GP out-of-hours services: lessons learned from an innovative approach. Educ Prim Care. 2018;29(6):376–380. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2018.1516517.

- Farmer J, Currie M, Hyman J, et al. Evaluation of physician assistants in National Health Service Scotland. Scott Med J. 2011;56(3):130–134. doi: 10.1258/smj.2011.011109.

- van der Biezen M, Derckx E, Wensing M, et al. Factors influencing decision of general practitioners and managers to train and employ a nurse practitioner or physician assistant in primary care: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s12875-017-0587-3.

- Wilson E, Hanson LC, Tori KE, et al. Nurse practitioner led model of after-hours emergency care in an Australian rural urgent care Centre: health service stakeholder perceptions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):819. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06864-9.

- Hansen EH, Boman E, Fagerström L. Perception of the implementation of the nurse practitioner role in a Norwegian out-of-hours primary clinic: an email survey among healthcare professionals and patients. Nordic Journal of Nursing Research. 2021;41(1):54–60. doi: 10.1177/2057158520964633.

- Christiansen A, Vernon V, Jinks A. Perceptions of the benefits and challenges of the role of advanced practice nurses in nurse-led out-of-hours care in Hong Kong: a questionnaire study. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(7-8):1173–1181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04139.x.

- Busca E, Savatteri A, Calafato TL, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of nurse’s role in primary care settings: an integrative review. BMC Nurs. 2021;20(1):171. doi: 10.1186/s12912-021-00696-y.

- Schadewaldt V, McInnes E, Hiller JE, et al. Views and experiences of nurse practitioners and medical practitioners with collaborative practice in primary health care – an integrative review. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14(1):132. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-132.

- Sangster-Gormley E, Martin-Misener R, Downe-Wamboldt B, et al. Factors affecting nurse practitioner role implementation in Canadian practice settings: an integrative review. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(6):1178–1190. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05571.x.