ABSTRACT

Background: Cosmetic dissatisfaction, pain, and chronic discharge may present months till years after enucleation in patients operated because of retinoblastoma. If noninvasive treatment modalities are insufficient, socket reconstruction can be considered. In this study, we discuss the results of dermis-fat exchange to treat these problems.

Method: Four patients with late onset post enucleation socket problems with a request for treatment were included in this prospective study. Socket inspection was documented and pictures at baseline and at a follow-up of at least 6 months were taken. To quantify the problem ‘pain’, a VAS score at baseline and at follow up was used. For the problem ‘cosmetic dissatisfaction’ standardized questionnaires were used.

Results: Two patients were included because of cosmetic dissatisfaction; one was included with chronic pain and one with chronic discharge. Reconstruction of the socket using autologous dermis-fat insertion was done in all four. In one of them, severe shrinking of the fat developed. This patient was treated with additional injectable fillers. Both of them, ultimately, had satisfactory results. Autologous fat transplantation also solved the problem of chronic discharge and pain in the two other patients.

Conclusion: Socket reconstruction by autologous dermis-fat exchange may solve different post enucleation socket problems. However, shrinking of the transplanted fat may occur and require additional procedures.

Introduction

Enucleation is a technically simple procedure with a low incidence of postoperative complications (Citation1). However, in prior studies, authors did identify different late problems after enucleation for retinoblastoma. These problems included chronic discharge from the socket (Citation2), persistent chronic socket pain, and dissatisfaction with the cosmetic outcome. We present a similar approach for these three different problems: socket revision by dermis-fat insertion.

The use of free-fat transplants to substitute volume in the anophthalmic socket was first described in the beginning of the twentieth century. Loewe (Citation3) introduced the fat transplant in conjunction with de-epithelized skin (composite grafts), the so called dermis-fat graft to overcome the significant atrophy which was seen in the free-fat transplants. In 1978, after years of disregard due to the introduction of the modern alloplastic implants, the use of dermis-fat grafts was resurrected by Smith and Petrelli (Citation3). They originally used the autologous dermis-fat grafts to replace an extruded (alloplastic) orbital implant (Citation3). Reports with variable success have been published using the dermis-fat implant as primary implant (Citation4-Citation8). Arguments in favor of the use of a autologous dermis-fat implant are: the possibility of deep fornix creation because the conjunctiva does not have to cover the anterior part of the dermis when closing the wound, less host-graft rejection than with an alloplastic implant and possibly orbital fat growth in children supporting expansion of the orbit (Citation9).

Nonetheless, the use of a dermis-fat implant is mainly reserved as secondary implant because of the disadvantage of the autologous technique: the need for a donor site (the buttocks or belly). Besides, surgical procedure takes longer (with prolonged anesthesia time), surgical outcome is less predictable than with the alloplastic orbital implant and operation room logistics (especially when using the buttock) are more complex.

The most common complications are central graft ulceration and graft atrophy (Citation10). Less common and more easily treated are graft infection, conjunctival granuloma’s, keratinization of the socket, and hair growth in the socket (Citation10). The rate of conjunctival advancement over the graft (which may be influenced by systemic vascular disease, previous socket trauma, multiple previous surgeries, and radiation therapy); cautery to the graft bed; use of oversized grafts with large anterior diameter; excessive manipulation of the graft during insertion; or excessive pressure on the graft postoperative are factors thought to predispose for central graft ulceration and atrophy (Citation11).

In addition to other successful reports (Citation12,Citation13), we report on four cases suffering from post enucleation socket problems rehabilitated by autologous dermis-fat insertion.

Method

In this prospective case series, four patients with an unsolved post enucleation problem were asked for study participation. Written informed consent was obtained. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Clinical history was obtained by patient interview and from the patients’ files. Problems were identified, as were potential previous (less invasive) treatment attempts. Follow-up was done by patient interview and photography. To measure the judgment of cosmetic outcome in patients treated for cosmetic reason, questionnaires of Face-Q were used (see attachment). These questionnaires were filled out by the patient before surgery, 6 weeks after surgery, and at last follow-up, at least 1 year after treatment. To quantify the problem ‘pain,’ a VAS score at baseline and at follow-up was used.

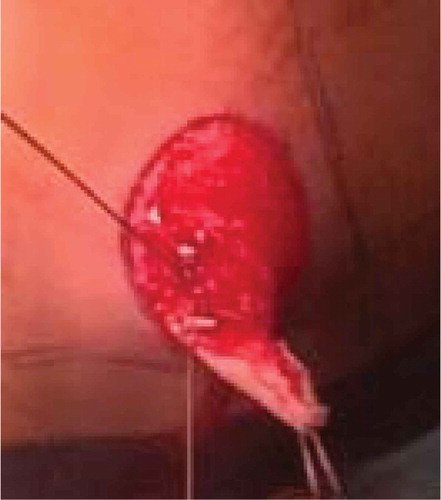

All problems were approached by revision of the socket using a dermis-fat-implant as described by Hintschich (Citation14). A dermis-fat graft was harvested from the upper outer quadrant of the buttock. The size of the graft was estimated by the size of the orbit and marked onto the buttock. Epidermis was dissected from the skin () and a round graft was excised using a number 10 mm surgical blade, obtaining a cylinder-shaped graft of epidermis and fat with a diameter of 20–25 mm.

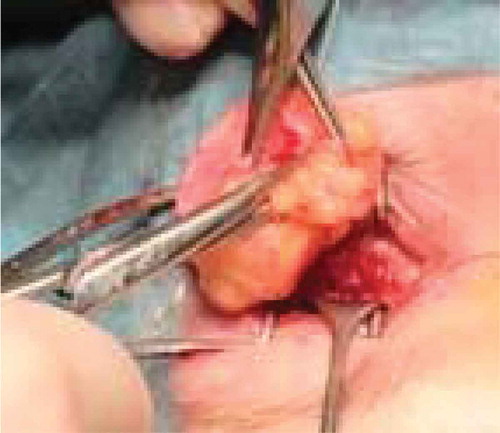

The donor site fat and epidermis were closed with novosyn 3-0 interrupting sutures, and the skin was closed with vertical Donati sutures using dafilon 2.0 or 3.0. After repositioning the patient, the socket was opened by a central horizontal incision of the conjunctiva and tenon. The rectus muscles were identified and anchored to vicryl 5-0 sutures, and – if present – the alloplastic implant was explanted. The dermis-fat graft was inserted into the intraconal space (Tenon’s capsula) with the dermis facing the front (). If necessary, the fat was additionally cut for the graft to fit in the intraconal space. Rectus muscles were sutured to the edge of the dermis. The conjunctiva was sutured onto the dermis over 360 degrees using interrupted novosyn 5.0 or 6.0 sutures leaving a central part of the dermis bare, so an adequately sized polymethylmethacrylate conformer could be positioned within the conjunctival fornices. Combined antibiotic and steroid ointment was applied direct postoperative and tobradex drops prescribed for 2–3 weeks. After 10 days, the sutures of the buttocks were removed and the healing of the orbit was evaluated. In one case, a secondary temporary tarsorrhaphy was placed because of excessive swelling and subsequent loss of the conformer.

Case 1 – cosmetic dissatisfaction

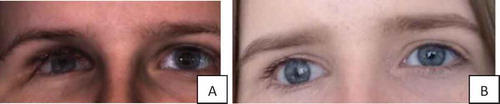

A 46-year-old retinoblastoma survivor, treated with enucleation without implant insertion at the age of 4, was not satisfied with the cosmetic outcome of the surgery (). The cause of his dissatisfaction was volume deficit because of the absence of an orbital implant. He regretted the limited prosthetic eye motility, the deep positioned prosthesis (enophthalmos effect), and the hollow aspect of his upper eyelid (superior sulcus deformity) ().

Table 1. Outcome of questionnaires in which patients’ personal experience and satisfaction with cosmesis were questioned in the two cases included with cosmetic dissatisfaction.

A dermis-fat implant was inserted and the identifiable rectus muscles were attached to the implant. The initial volume of the dermis-fat appeared too much (); however, when the swelling came down, the volume shrunk and a new prosthetic eye could be fit 2 months postoperative. Although a gain of volume and prosthesis motility was seen, a (decreased) deepening of the superior sulcus persisted (). To improve orbital volume, we injected 2 cc Restylane® filler in the inferolateral orbital region (1-year postsurgery) and another 1 cc below the superior orbital rim to improve the superior sulcus 3 months later. At 1.5 years post dermis-fat implantation (), the patient reported cosmetic satisfaction () and did not request additional Restylane filling.

Case 2 – cosmetic dissatisfaction

A 19-year-old girl, enucleated at the age of 3 months for the treatment of unilateral retinoblastoma, was unsatisfied with the cosmetic ocular appearance (). In her case, an implant had been inserted directly after enucleation, but it extruded, and after this complication, the socket was left empty. Apart from the lack of volume, she was unsatisfied with the position of the eyelids. She carried her hair over one side of her face to cover the artificial eye. At inspection, she had a shallow inferior fornix pushing the prosthesis upwards, an entropion of the lower eyelid and retraction of the upper eyelid. Dermis-fat implantation was performed. Postoperative recovery was uncomplicated. At 2 years follow-up, patient reported satisfaction (). (See for photo’s before and after surgery.)

Case 3– socket pain

A 26-year-old woman (), enucleated for unilateral retinoblastoma at 1.5 years, endured intolerable pain for at least 10 years. She could not bear wearing her ocular prosthesis. VAS score varied between 7 and 9. She refused permanent pain medication and requested a socket revision. Her socket did not show any abnormalities at inspection, but her medical history revealed repeated problems and surgical interventions after the primary enucleation with insertion of an Allen implant of 20 mm: 1 month after surgery, fornix deepening sutures were placed because of prolapsing conjunctiva, later the inferior rectus muscle was repositioned because of a tilted prosthesis, followed by symblepharon removal, and 2 years later, the 20 mm Allen implant was replaced by a 18 mm sized Allen implant because of a shallow inferior fornix. One year thereafter (at age 4), the Allen implant was replaced by a 16 mm acrylic implant wrapped in donor sclera.

At physical examination the socket appeared quiet with deep fornices, no symblepharon, and no implant exposure.

MR imaging did not show any abnormalities (). Since previous reimplantation of the alloplastic implant had been performed (with decreasing size) and proved unsuccessful, we chose to remove the acrylic implant and replace it with an autologous dermis-fat implant. One month postoperative, an infection complicated the wound healing (), after topical antibiotic treatment with tobramycine ointment, a hole was seen as result of local fat necrosis (). Revision surgery followed: umbilical fat was used to fill the hole, covered with mucosal membrane of the mouth. Follow-up of this surgery was uncomplicated although overall volume loss of the transplanted fat was seen resulting in a deep socket with hollow superior sulcus. Although cosmetic satisfaction was not obtained (), patient reported to have less pain (VAS of 0–4 varying over time) since the primary intervention at follow-up, 9 months after (although she experienced an interval of pain due to infection and postoperative pain after the second surgery).

Case 4- chronic discharge

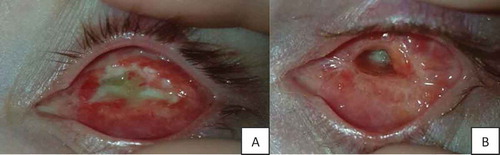

A 9-year-old boy was inflicted with chronic discharge of his socket. At 3 months old, his left eye was enucleated for the treatment of bilateral retinoblastoma. His other eye was treated with external beam radiation therapy (EBRT). Complaints of socket discharge started 2 years after surgery. Attempts made to resolve this problem included polishing of the prosthesis, renewal of the prosthesis, different prosthesis cleaning schemes, artificial tears, vismed wash (an antimicrobial solution), massage of the lacrimal sac combined with eyelid hygiene measures, a switch from prosthesis made of PMMA to one made of glass, different local antibiotic treatments, oral antibiotics, and a S. aureus eradication treatment (Citation2). Physical examination repeatedly demonstrated dried mucus around the eyelids, accumulation of discharge at the prosthesis and the eyelid margins, upper eyelid entropion with lashes stuck onto the prosthesis, and a hyperemic socket (). No giant papillae were seen and no itching signs were reported. At MR imaging, no signs of implant infection or pus collections were shown.

The solution proved to be a structural change of the socket anatomy. The acrylic implant was removed and replaced by an autologous dermis-fat implant. In addition, lash everting sutures (novosyn 5.0) were placed in his upper eyelid. At follow-up, patient (and mother) reported an evident decrease of mucosal discharge, with the secondary gain of experiencing more self-esteem and happiness. At inspection after 3,5 months, entropion of the upper eyelid recurred, and the fat was partly resorbed resulting in a more enophthalmic appearance than was present before surgery as result of the EBRT. Nonetheless, the socket remained quiet with minimal mucosal discharge ().

Discussion

Dermis-fat insertion following socket revision can be an adequate rehabilitative treatment for different post enucleation socket problems. Treatable complications are however not uncommon (Citation15).

In these series, even though very experienced orbital surgeons performed surgery, two cases were complicated: one had a central graft ulceration and graft atrophy and the other had graft atrophy. In retrospect, we recognize several factors predisposing the risk of complication in these patients; in the case with central ulceration and graft atrophy, multiple surgeries had preceded, making her recipient bed less vital. Also cautery to the recipient bed was performed because of an arterial bleed. In the second case, the graft might have been oversized, which might have led to excessive manipulation during introduction and extensive pressure postoperative. In the ‘discharge case,’ the main goal was achieved; however, also in this case, the cosmetic outcome regarding the volume and eyelid position was disappointing. The risk of graft absorption in this case was enhanced due to his history of EBRT.

Kuzmanović Elabjer et al. reported ~20–40% dermofat resorption due to lipolysis and adipose tissue resorption (Citation16). The average report of volume loss after primary dermis-fat grafting is 5–10%, but it is known that secondary grafts suffer more resorption (Citation8,Citation17).

As a solution for the cases with unacceptable graft shrinkage, secondary volume augmentation with a repeat (larger) dermis-fat implant (Citation8,Citation9) or with hydroxyapatite blocks (Citation9) are presented in literature; however, report on the final outcome in these cases are lacking.

Additional umbilical fat insertion with buccosal mucous coverage was not effective in our presented case.

A less invasive procedure for cosmetic volume augmentation is injection with soft-tissue filler. Although autologous fat can be used for injection, avoiding the harvesting and potentially repeated resorption, the use of allogeneic fillers was preferred. Rare complications following injection with various available fillers in the periorbital region include granuloma formation, infection, skin necrosis, scarring, vascular occlusion, and orbital cellulitis (Citation15,Citation16).

With injectables the location of the desired volume and amount of suppletion can be adapted. However, predictability requires experience since every filler material has its distinct composition, injection profile, and duration of effect (Citation18,Citation19). Injection of permanent or semi-permanent fillers in the periorbital region is discouraged because of potential lumps or beading. Dislocation of the filler or overcorrection is difficult to reverse (Citation18). To avoid display of irregularities, firm massage can be applied promptly after injection (Citation18). Today, no negative long-term effects, negative effects of repetitive injection, or oncogenic effects of Restylane in retinoblastoma patients have been reported.

In our presented case, injection with Restylane was done twice to obtain an adequate volume, subjectively this volume effect was still present at 8 months follow-up.

In conclusion, these series demonstrate that socket revision and insertion of an autologous dermis-fat implant subjectively improved cosmetics in one case, resolved persistent socket pain and resolved a case of chronic discharge from the socket. Despite these successes, volume restoration by dermis-fat implantation only was disappointing in three of four cases. Volume substitution with temporary fillers might be an effective alternative or supplemental treatment modality.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Mourits DL, Moll AC, Bosscha MI, Tan HS, Hartong DT. Orbital implants in retinoblastoma patients: 23 years of experience and a review of the literature. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015;94(2):165–74. doi:10.1111/aos.12915.

- Mourits, DL, Hartong, DT, Budding, AE, Bosscha, MI, Tan, HS, Moll, AC. Discharge and infection in retinoblastoma post-enucleation sockets. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11.465–72. doi:10.2147/OPTH.

- Smith B, Dermis-Fat PR. Graft as a movable implant within the muscle cone. Am J Ophthalmol. 1978;85(1):62–66. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(14)76666-8.

- Quaranta-Leoni FM, Sposato S, Raglione P, Mastromarino A. Dermis-fat graft in children as primary and secondary orbital implant. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;32(3):214–19. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000000471.

- Nunery WR, Hetzler KJ. Dermal-fat graft as a primary enucleation technique. Ophthalmology. 1985;92(9):1256–61. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(85)33882-4.

- Tarantini A, Hintschich C. Primary dermis-fat grafting in children. Orbit. 2008;27(5):363–69. doi:10.1080/01676830802345125.

- Hauck MJ, Steele EA. Dermis fat graft implantation after unilateral enucleation for retinoblastoma in pediatric patients. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;31(2):136–38. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000000228.

- Nentwich MM, Schebitz-Walter K, Hirneiss C, Hintschich C. Dermis fat grafts as primary and secondary orbital implants. Orbit. 2014;33(1):33–38. doi:10.3109/01676830.2013.844172.

- Heher KL, Katowitz JA, Low JE. Unilateral dermis-fat graft implantation in the pediatric orbit. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;14(2):81–88. doi:10.1097/00002341-199803000-00002.

- Bosniak SL. Complications of dermis-fat orbital implantation. Adv Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;8.170–81.

- Bosniak SL. Avoiding complications following primary dermis-fat orbital implantation. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;1(4):237–41. doi:10.1097/00002341-198501040-00004.

- Aggarwal H, Singh K, Kumar P, Alvi HA. A multidisciplinary approach for management of postenucleation socket syndrome with dermis-fat graft and ocular prosthesis: a clinical report. J Prosthodont. 2013Dec. 22(8):657–60. doi:10.1111/jopr.12051.

- Shams PN, Bohman E, Baker MS, Maltry AC, Dafgard Kopp E, Allen RC. Chronic anophthalmic socket pain treated by implant removal and dermis fat graft. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99(12):1692–96. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-306585.

- Guthoff R, Katowitz J. Dermis fat implants. In: Krieglstein GK, Weinreb RN editors. Oculoplastics and orbit, (2007) essentials in ophthalmology. Springer. Berlin, Heidelberg. 2007;181–94.

- Baum SH, Schmeling C, Pförtner R, Mohr C. Autologous dermis-fat grafts as primary and secondary orbital transplants before rehabilitation with artificial eyes. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2018;46(1):90–97. doi:10.1016/j.jcms.2017.09.005.

- Kuzmanović Elabjer B, Bušić M, Bosnar D, Elabjer E, Miletić D. Our experience with dermofat graft in reconstruction of anophthalmic socket. Orbit. 2010;29(4):209–12. doi:10.3109/01676830.2010.485716.

- Martin PA, Rogers PA, Billson F. Dermis-fat graft: evolution of a living prosthesis. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1986;14(2):161–65. doi:10.1111/(ISSN)1440-1606.

- Ozturk CN, Li Y, Tung R, Parker L, Piliang MP, Zins JE. Complications following injection of soft-tissue fillers. Aesthetic Surg J. 2013;33(6):862–77. doi:10.1177/1090820X13493638.

- Sia PI, Rajak SN, Benger RS, Selva D. Orbital cellulitis from facial tissue fillers Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2017;45(6):648–51. doi:10.1111/ceo.12930.