?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Objective: The Relative Value Unit (RVU) system was initially developed to account for costs associated with clinical services and has since been applied in some settings as a metric for monitoring productivity. That practice has come under fire in the medical literature due to perceived flaws in determination of “work RVU” for different billing codes and negative impacts on healthcare rendered. This issue also affects psychologists, who bill codes associated with highly variable hourly wRVUs. This paper highlights this discrepancy and suggests alternative options for measuring productivity to better equate psychologists’ time spent completing various billable clinical activities. Method: A review was performed to identify potential limitations to measuring providers’ productivity based on wRVU alone. Available publications focus almost exclusively on physician productivity models. Little information was available relating to wRVU for psychology services, including neuropsychological evaluations, specifically. Conclusions: Measurement of clinician productivity using only wRVU disregards patient outcomes and under-values psychological assessment. Neuropsychologists are particularly affected. Based on the existing literature, we propose alternative approaches that capture productivity equitably among subspecialists and support provision of non-billable services that are also of high value (e.g. education and research).

Thirty years ago, the Resource-Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS) was developed by The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in response to rising health care costs due to variable payments for the same medical procedures and services across the country (Beck & Margolin, Citation2007). The original RBRVS considered total physician work, practice costs (e.g. professional liability insurance), and specialty-specific costs to calculate a nonmonetary value to determine physician reimbursement (Hsiao et al., Citation1992). Since then, many medical institutions have adopted the RBRVS as a measure of provider productivity (Laugesen, Citation2014; Nurok & Gewertz, Citation2019). Given that 37.5% and 42% of neuropsychologists who responded to recent surveys indicated that their income is based on a quota or clinical productivity expectation, establishing reasonable clinical productivity targets is highly important (Petranovich et al., Citation2023; Sweet et al., Citation2021). While some literature exists relating to productivity expectations among physician subspecialists, we found few articles that specifically pertain to the impact of different wRVUs associated with psychology billing codes, productivity targets, and potential effects on compensation and job satisfaction among psychology subspecialists. This paper reviews relevant literature and proposes alternative approaches to improve parity in productivity expectations specifically for psychology subspecialists.

Relative value unit (RVU) basics

RVUs are the base scale unit of the RBRVS. Total RVUs are a summation of 1. Provider work RVUs (i.e. wRVU), 2. Practice expense RVUs, and 3. Professional liability insurance RVUs. The CMS payment structure averages approximately 52% for provider work, 44% for practice expenses, and 4% for professional liability insurance (Maxwell & Zuckerman, Citation2007). Practice expense RVUs differ depending on the setting in which a service is rendered (i.e. facility versus non-facility) because facilities bill a separate charge to cover higher overhead expenses (Maxwell & Zuckerman, Citation2007). Total RVUs are adjusted to account for variations across geographical regions in practice costs, such as wages and malpractice premiums (Baadh et al., Citation2016). They are then multiplied by a set conversion factor, which is currently approximately $34.61 (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Citation2022). Unique RVUs are associated with each Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code developed by the American Medical Association to determine reimbursement levels for all medical and psychological services (Gao, Citation2018). CPT codes are updated annually to allow for new procedures to be included. However, RVUs have been criticized as being outdated and potentially biased, as the RVUs for only 2% of CPT codes are re-evaluated each year and the data used to determine RVUs per CPT code is based on self-report responses by relatively small numbers of providers (Urwin & Emanuel, Citation2019). Furthermore, the data is proprietary and therefore lacks transparency.

wRVUs as a measure of productivity

While wRVUs were initially designed as a measure of physician effort associated with individual CPT codes for consistent billing practices across the nation, they have since become used to systematically measure provider productivity (Satiani et al., Citation2012). wRVUs are determined as the amount of physician time associated with a specific CPT code multiplied by a compensation rate described as “intensity,” which reflects the perceived amount of mental effort, stress, and technical skill required for each specific service (Childers & Maggard-Gibbons, Citation2020). This “intensity” value results in different wRVUs for medical services that may otherwise take approximately the same amount of time to complete.

Through annual surveying across health organizations, provider compensation is often determined using survey data related to cash compensation and wRVU. American Medical Group Association (AMGA), Medical Group Management Association (MGMA), Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), Vizient, and SullivanCotter are five popular healthcare provider productivity survey companies whose data is used to determine provider salaries and productivity targets, which healthcare organizations then use to determine fair market price benchmarks for compensation. They are also sometimes used to determine productivity targets. In a survey completed by 78 department chairs of academic medical institutions located across the United States, 82% of respondents indicated that they use productivity targets to determine salary compensation. Of those that indicated using productivity to determine compensation, 84% reported the use of data provided by one of the survey companies to determine a standardized RVU productivity target (Kairouz et al., Citation2014). As with the RVU determination process, these salary survey companies are purported to rely on relatively small samples of self-reported data and the data is proprietary (Rosner & Falk, Citation2020).

wRVUs among physician specialties

Physicians from multiple specialties have expressed concern about the exclusive use of wRVU to evaluate productivity and salaries. For example, physicians in Gastroenterology, General Internal Medicine, Radiology, and Pediatric Nephrology have argued either for significant changes to the current wRVU system or for a shift away from wRVUs as a productivity target altogether (Katz & Melmed, Citation2016; Linzer et al., Citation2016; Sebro, Citation2021; Weidemann et al., Citation2022).

One concern is that wRVU values differ substantially depending on physician specialty, yet wRVU targets at some institutions may not acknowledge those differences. For example, compensation rates are lowest in Pathology (0.029 wRVUs/min) and highest in Emergency Medicine (0.057 wRVUs/min), with most specialties falling between a range of 0.035 and 0.045 wRVUs/min (Childers & Maggard-Gibbons, Citation2020). Additionally, as noted above, the “intensity” value associated with each CPT code does not appear well-defined. Furthermore, there is a clear emphasis on “procedure-based activities” among physician codes (e.g. surgery), as those activities are compensated at disproportionately higher rates than what is described in the literature as “cognitive care” (i.e. standard outpatient visits that do not involve a medical procedure; Childers & Maggard-Gibbons, Citation2020). There is concern that physicians will shift their practices away from preventative care and towards more intensive procedures to achieve a higher average wRVU (Rosner & Falk, Citation2020). Sole determination of productivity using wRVUs also over-emphasizes quantity over quality health care and devalues non-wRVU generating activities, such as participation in interdisciplinary team meetings, case conferences, and case consultation with trainees (Katz & Melmed, Citation2016).

In addition to potentially impacting standard physician practices, a purely wRVU-based model for productivity has been associated with greater job dissatisfaction and physician burnout due to pressure to increase work output (Dillon et al., Citation2020; Rosner & Falk, Citation2020; Zupanc et al., Citation2020). Recently, the Child Neurology Society examined physician burnout in the context of increased workload associated with wRVU productivity targets and determined that reliance on wRVU alone discourages participation in training, reviewing laboratory results, and peer consultation, which then increases the risk for reduced quality of patient care (Zupanc et al., Citation2020). To combat those issues, the task force recommended incorporation of revenue and participation in activities necessary for promotion, such as trainee mentorship and teaching, within the provider productivity model. Indeed, some institutions have created an “academic RVU” that gives pre-determined, weighted credit for teaching and research endeavors that are particularly important for consideration of promotion within academic medical centers (Carlson, Citation2021; Guiot et al., Citation2017; Ma et al., Citation2017; Stites et al., Citation2005).

wRVUs for psychology codes

With regard to psychologists, there is considerable discrepancy in hourly wRVU accessible to psychologists who perform mostly assessment versus intervention services even though psychologists helped to determine them (American Psychological Association, Citation2020; Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Citation2022). Unfortunately, many institutions that use wRVU targets to measure productivity rely on published salary benchmarks that do not distinguish psychology subspecialists (Brosig et al., Citation2017). That may be of little concern when it comes to salary, but it is problematic for subspecialist psychologists who primarily bill CPT codes associated with lower hourly wRVU, such as neuropsychological evaluation codes.

illustrates the current wRVU associated with commonly billed psychotherapy and intervention codes. While psychotherapy codes are relatively simple, health and behavior codes and assessment codes include a base code and an add-on code. Whereas a standard psychiatric intake interview is associated with 3.84 wRVU and a standard 60-minute outpatient psychotherapy appointment is associated with 3.31 wRVU, an hour-long health and behavior appointment is valued at only 2.45 wRVU (i.e. 25% less wRVU than a 60-minute standard psychotherapy session).

Table 1. 2022 wRVU for commonly billed psychotherapy and other treatment codes.

reflects the current wRVU associated with commonly used psychological assessment codes. Billing for a psychological/neuropsychological evaluation varies as a result of how comprehensive or complex an evaluation must be to answer the referral question (American Psychological Association, Citation2019). Illustration of the hourly wRVU for psychological and neuropsychological assessment is also more complicated because of the implementation of base codes and add-on codes in 2019 combined with whether a psychometrist assists with the testing. and provide a sample of the neuropsychological billing and associated hourly wRVU that may be rendered for a standard outpatient evaluation, with and without psychometrist assistance, respectively. What is apparent from those tables is that, when considering the psychologist’s time, psychotherapy is associated with a much higher hourly wRVU (3.31 wRVU) in comparison to the average hourly rate for a standard neuropsychological evaluation, particularly if the evaluation is conducted without assistance of a psychometrist (2.09 wRVU and 1.49 wRVU, respectively). That is a difference of up to 55% fewer wRVUs per hour for neuropsychologists conducting neuropsychological evaluations without assistance of a psychometrist. Of note, referencing the 2020 Salary Survey, only 53% of practicing clinical neuropsychologists utilize psychometrist support (Sweet et al., Citation2021).

Table 2. 2022 wRVU for psychological and neuropsychological assessment CPT codes.

Table 3. Example total wRVU for a neuropsychological evaluation, with psychometrist assistance.

Table 4. Example total wRVU for a neuropsychological evaluation, without psychometrist assistance.

It is worth noting that billing for trainees differs across level of trainee per state and national regulations. In general, trainees can bill as psychometrists, which renders zero wRVU for the supervising neuropsychologist. However, some states, such as Michigan, allow postdoctoral fellows to bill on their own license, which again would not render any wRVU to the supervising neuropsychologist. Although dated since the 2019 revision in neuropsychological CPT codes, readers may refer to Rosenstein’s (Citation2017) paper for more information on student billing for their role in neuropsychological evaluations.

Potential consequences of sole reliance on wRVU productivity targets

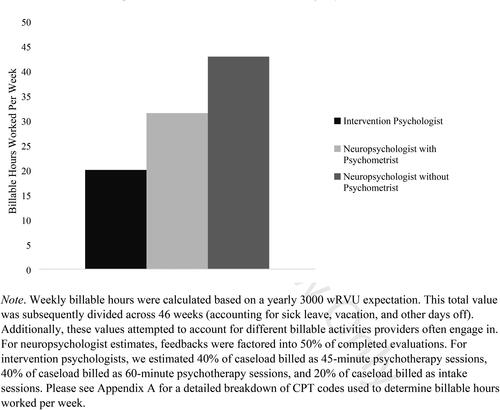

While it could be argued that the value of assessment and intervention services rendered by psychologists is equivalent, this is clearly not reflected by the wRVU assigned to the above codes. The documented rationale for the different wRVU assigned to each CPT code is the degree of “time and intensity” required for the service. Each code billed by psychologists already factors in time, so the issue seems to be disagreement in the perceived intensity, or possibly the value, of assessment versus intervention services. This is confusing, especially given the much more stringent training requirements for neuropsychologists versus the range of provider types who bill psychotherapy codes (e.g. psychologists and master’s level social workers and counselors) and the fact that neuropsychological and psychological evaluations are sometimes required prior to consideration for certain surgeries (e.g. Labiner et al., Citation2010; NAN, Citation2001; Sogg et al., Citation2016). Regardless, the discrepancy in hourly wRVU attributed to intervention versus assessment codes creates issues for providers at institutions where wRVU targets are consistent across all psychologist subspecialists. Specifically, existing wRVU targets published by at least AAMC and Sullivan Cotter, to our knowledge, have not historically distinguished between different psychologist subspecialists. Therefore, use of a single wRVU productivity target across subspecialists translates literally to more hours worked for psychologists whose practice primarily focuses on assessment (see for estimated hourly discrepancies).

Figure 1. Estimated hours worked per week to meet an annual wRVU target of 3000.

Note. Weekly billable hours were calculated based on a yearly 3000 wRVU expectation. This total value was subsequently divided across 46 weeks (accounting for sick leave, vacation, and other days off). Additionally, these values attempted to account for different billable activities providers often engage in. For neuropsychologist estimates, feedbacks were factored into 50% of completed evaluations. For intervention psychologists, we estimated 40% of caseload billed as 45-minute psychotherapy sessions, 40% of caseload billed as 60-minute psychotherapy sessions, and 20% of caseload billed as intake sessions. Please see Appendix A for a detailed breakdown of CPT codes used to determine billable hours worked per week.

The 2020 Neuropsychology Salary Survey (Sweet et al., Citation2021) assessed work/life balance satisfaction using a 0–100 scale. There was quite a range in responses, reflecting clear room for improvement for many neuropsychologists (mean = 70.2, median = 78.0, standard deviation = 24.8). Unrealistic billing or RVU expectations was identified as a reason for changing positions for a minute number of respondents. Nevertheless, clinical hours worked negatively correlated with both job satisfaction and work/life balance at the p < .001 level. While the effect sizes were relatively small, those findings are consistent with a recent survey of pediatric rehabilitation neuropsychologists, which identified workload and billing as top job-related concerns among 50% of the respondents (Petranovich et al., Citation2023). Of importance, some institutions threaten a loss of income when productivity expectations are not met, which can also influence job and income satisfaction (Sweet et al., Citation2021). Excess productivity targets might also interfere with participation in non-billable activities, such as case consultation, interdisciplinary team meetings, patient rounding, and trainee supervision, which could then interfere with promotion eligibility (Johnson-Greene, Citation2018. Petranovich et al., Citation2023). Finally, it is well documented that excess work hours and imbalanced work/life responsibilities can cause trickle-down effects, such as diminished mental and physical health, as well as burnout (Feigon et al., Citation2018; Sweet et al., Citation2021).

Other factors unique to neuropsychologists can affect their productivity, some of which are outside of their control. Unfortunately, little has been published on this topic, so some of the following information is based on the clinical experience of the authors. Perhaps the most significant factor unique to neuropsychologists that can affect their productivity is psychometrist turnover, which can affect two to three months’ worth of productivity in a single year due to the time it takes to post the position, interview, hire, and then train the new psychometrist. An issue that is not unique to neuropsychologists and psychologists who do primarily assessment but may impact them more than other types of clinicians is patient no-shows. A patient who no-shows a neuropsychological or psychological evaluation or refuses or is otherwise unable to participate can affect four plus hours of the psychologist’s billable time, which is a much higher impact than a no-show for a one-hour psychotherapy appointment. While no-show rates vary, one study found that 42% of patients referred for a post-surgical neuropsychological evaluation did not follow through with their appointments, which would result in an incredible impact on clinician productivity (Mark et al., Citation2014). There is also the issue of insurance pre-authorization, which is vital for neuropsychological evaluations since a single evaluation often costs thousands of dollars; we are aware of some institutions that offer minimal administrative support and require psychologists or sometimes their trainees to complete insurance pre-authorization, which is time-consuming, not billable, and readily completed by appropriately trained clerical staff.

As noted above, there are several other documented risks of sole reliance on wRVU targets as a measure of productivity within the physical literature, including over-emphasis on quantity of billable activities without consideration for work quality, reduced participation in non-billable activities such as training and research in the absence of protected time, and shifting of professional activities towards those that render higher wRVU (Childers & Maggard-Gibbons, Citation2020; Katz & Melmed, Citation2016; Rosner & Falk, Citation2020). All of those risks could impact psychologists and neuropsychologists, as well.

Possible solutions

If wRVU is the only option considered by institution administration as an indicator of clinical productivity, one possibility that will at least help clinicians who currently conduct their own testing is to enable the use of psychometrists (see and ), whose services are more cost-efficient given their lower hourly salaries, which enables more patients to be evaluated each week (DeLuca & Putnam, Citation1993). Their assistance also enables neuropsychologists to have more flexible schedules, freeing up time for important activities such as patient care conferences and teaching/research-related activities. Psychometrists can also assist with other non-billable activities when caught up with patient responsibilities (Feigon et al., Citation2018). Notably, in the most recent 2020 Neuropsychology Salary Survey (Sweet et al., Citation2021), 66% of ABCN-certified providers and 46% of ABN-certified providers indicated they utilize psychometrist support. However, working with psychometrists only reduces the gap in productivity expectations, it does not close it.

An alternative resource that neuropsychologists may reference is the 2020 Neuropsychology Salary Survey (Sweet et al., Citation2021), which received responses from over 1500 neuropsychologists and includes tables on neuropsychologists’ salaries across different types of institutions and at different faculty ranks or years of service. That peer-reviewed publication includes mean and median RVU targets. Unfortunately, it does not appear that respondents were asked to specify work RVU (wRVU) targets (versus total RVU). Furthermore, while percent full-time equivalent (FTE) is noted, it is unclear whether some respondents have protected time for other activities, such as research or administrative responsibilities, which could skew results. Furthermore, some institutions rigidly adhere to a single survey company’s data across all types of providers, which can limit whether neuropsychologists are able to reference that peer-reviewed article when advocating for their salary or wRVU target.

In the event of rigid adherence to proprietary salary and productivity target data, neuropsychologists can request that a conversion factor be implemented to equate neuropsychologists’ and psychologists’ time spent on clinical activities. For example, institution administration can offset psychologist wRVU differences using the following conversion formula:

For example: Using a target psychologist wRVU of 3000, a mean hourly neuropsychologist wRVU is 2.09 (with psychometrist assistance; see ) and a mean hourly wRVU for intervention psychologists is 2.78 (assuming that 50% of their cases are billed using 90834 and 50% are billed using 90837):

The above example is easy enough to explain to hospital administrators and results in approximately a 25% reduction in target wRVU for neuropsychologists, making their hourly expectations comparable to other psychologists who typically bill psychotherapy codes. The resulting average wRVU is also much closer to the mean wRVU target reported on the 2020 Neuropsychology Salary Survey for neuropsychologists at .8 to 1.0 FTE (M = 2195, SD = 613.6; Sweet et al., Citation2021). Of interest, the 95th percentile wRVU target in the 2020 Neuropsychology Salary Survey was 3200, falling just below the wRVU productivity target for all psychologists at our institution at the time this manuscript was prepared.

The primary limitation to the conversion approach to equating psychologists’ time is that it falls short for providers who offer a variety of services, such as neuropsychological evaluations (especially if psychometrist support is not consistently available), traditional psychotherapy, and/or cognitive rehabilitation. Identifying individual wRVU targets can become cumbersome for psychologists engaged in multiple services. Alternative methods for determining productivity expectations among psychologists have been documented using surveys of adult and pediatric neuropsychologists (Petranovich et al., Citation2023;; Sweet et al., Citation2021). For example, some neuropsychologists’ productivity expectations/salaries are based on hours billed, revenue generated, or some combination of those factors and wRVU generated. Specifically, 12% of respondents in the 2020 Neuropsychology Salary Survey indicated that their income was based on hours worked and another 20% of respondents indicated that their income was based on amount of revenue generated (Sweet et al., Citation2021). It is important to note that placing direct emphasis on generated revenue can be risky due to perhaps untoward, but nevertheless egregious, consequences, such as avoidance of providing services for already marginalized patient populations because their health insurances reimburse at a low rate (Petranovich et al., Citation2023).

Out of all of the above options, the easiest solution is likely focusing on total hours billed, particularly given that some providers offer a wide range of services and may therefore use a range of CPT codes. This approach still accomplishes the goal of direct comparison of productivity across providers and enables psychologists and neuropsychologists to divide their clinical responsibilities based on their patients’ and/or departments’ needs. It also clearly enables the division of clinical responsibilities from other valuable commitments, thereby potentially protecting some time for non-billable services such as teaching and research. If measurement of productivity in hours billed is considered infeasible, alternative methods to ensure time for activities considered necessary to accomplish the tripartite mission (i.e. clinical work, education, and research) and for consideration of promotion in academic medical centers include offering a percent of protected time for non-billable activities or implementation of educational/academic value units, as already noted (Carlson, Citation2021; Guiot et al., Citation2017; Ma et al., Citation2017; Stites et al., Citation2005).

Limitations

As already noted, the biggest limitation to this manuscript is the relative dearth of existing literature on psychology and neuropsychology productivity expectations and associated personal and professional outcomes. Every effort was made to rely on research when feasible, but some content is nevertheless based on professional experience, personal communication with neuropsychologists at other institutions, and monitoring of the American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology listserv that is accessible to providers with board certification through the American Board of Professional Psychology. Many neuropsychologists rely on such forums to manage the business aspects of clinical practice, in part because the topics of billing and productivity targets are continually evolving and are often site- or state-specific. We also borrowed heavily on available literature on physicians in academic medical centers in an effort to extrapolate potential consequences, but much remains to be objectively quantified on this topic.

Future steps

One thing that came to light while working on this paper was the limited transparency of how wRVUs were determined for neuropsychology and other assessment codes. Future studies might survey psychologists and neuropsychologists on their work RVU targets, whether they have protected time or potential to earn educational/academic RVUs, and the specific bases for their salaries and potential risks to their salaries. Separating out responses on wRVU targets from neuropsychologists at academic medical centers versus Veterans Affairs institutions, non-academic settings, and private practice might also be beneficial. Furthermore, additional studies are needed that evaluate the impact of productivity targets on professional goals (e.g. promotion, engagement with trainees), as well as on consequences (e.g. burnout, reduced satisfaction).

We are hopeful that quality of care will become more routinely considered as a measure of provider practice and that the gaps in wRVU associated with various psychological services close given the high value of each service. To that end, psychologists and neuropsychologists interested in creating wRVU that more accurately reflect the “intensity” of their work are encouraged to become engaged with in professional organizations, such as the American Psychological Association, the Inter Organizational Practice Committee, and the Society for Clinical Neuropsychology Public Interest Advisory Committee, all of which target topics of national importance. If wRVU targets are here to stay as a productivity indicator, it would be great if members of those organizations can become involved with the American Medical Association/Specialty Society Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC), which provides recommendations to CMS regarding RVU values that are accepted by CMS more than 90% of the time with no modifications (Chan et al., Citation2019). That committee is currently composed of only 32 physicians, and while psychiatry is represented, there were no psychologists on the committee at the time this article was prepared (American Medical Association, Citation2022; An introduction to the RUC, Citation2021). Indeed, having a representative within your specialty on the RUC is associated with a 3 to 5% increase in reimbursement for services provided by that specialty (Gao, Citation2018). That said, the RUC is not without criticisms relating to conflicts of interest, small committee size, and limited transparency (Urwin &

Emanuel, Citation2019). Advocacy efforts could alternatively focus on establishing equitable productivity determinants that can be applied across psychologist subspecialists in a variety of settings and might further incorporate ways to value both billable and non-billable activities.

Conclusion

It is clear that sole reliance on wRVU as a marker for work productivity for psychologists is problematic, for the many reasons described above. We hope this commentary stimulates future discussion and research at organization leadership levels regarding how to more equitably measure psychologists’ productivity and participation in other professional activities. Leadership may look to how other institutions handle these issues, such as by measuring hours billed rather than wRVU or offering protected time or academic RVUs, to more directly support the many valuable activities psychologists render.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflicts of interest were reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Medical Association. (2022). Composition of the RVS update committee (RUC). Retrieved December 12, 2022 from https://www.ama-assn.org/about/rvs-update-committee-ruc/composition-rvs-update-committee-ruc

- American Psychological Association. (2019). 2019 Psychological and neuropsychological testing billing and code guide. Retrieved July 30, 2022, from https://www.apaservices.org/practice/reimbursement/health-codes/testing/billing-coding-addendum.pdf

- American Psychological Association. (2020, December). Psychologists likely to see increases for psychotherapy services, but pay cuts for other services in Medicare for 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2022, from https://www.apaservices.org/practice/reimbursement/government/psychotherapy-services

- An introduction to the RUC. (2021). Retrieved December 12, 2022 from www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2021-04/introduction-to-the-ruc.pdf

- Baadh, A., Peterkin, Y., Wegener, M., Flug, J., Katz, D., & Hoffmann, J. C. (2016). The relative value unit: History, current use, and controversies. Current Problems in Diagnostic Radiology, 45(2), 128–132. https://doi.org/10.1067/j.cpradiol.2015.09.006

- Beck, D. E., & Margolin, D. A. (2007). Physician coding and reimbursement. The Ochsner Journal, 7(1), 8–15.

- Brosig, C. L., Hilliard, M. E., Williams, A., Armstrong, F. D., Christidis, P., Kichler, J., Shroff Pendley, J., Stamm, K. E., & Wysocki, T. (2017). Society of pediatric psychology workforce survey: Factors related to compensation of pediatric psychologists. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 42(4), 355–363. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsx051

- Carlson, E. R. (2021). Academic relative value units: A proposal for faculty development in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 79(1), 36.e1–36.e13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2020.09.036

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2022, July). Physician fee schedule. Retrieved August 8, 2022, from https://www.cms.gov/medicare/physician-fee-schedule/search/license-agreement?destination=/medicare/physician-fee-schedule/search%3F

- Chan, D. C., Huynh, J., & Studdert, D. M. (2019). Accuracy of valuations of surgical procedures in the medicare fee schedule. The New England Journal of Medicine, 380(16), 1546–1554. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1807379

- Childers, C. P., & Maggard-Gibbons, M. (2020). Assessment of the contribution of the work relative value unit scale to differences in physician compensation across medical and surgical specialties. JAMA Surgery, 155(6), 493–501. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2020.0422

- DeLuca, J. W., & Putnam, S. H. (1993). The professional/technician model in clinical neuropsychology: Deployment characteristics and practice issues. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 24(1), 100–106. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.24.1.100

- Dillon, E. C., Tai-Seale, M., Meehan, A., Martin, V., Nordgren, R., Lee, T., Nauenberg, T., & Frosch, D. L. (2020). Frontline perspectives on physician burnout and strategies to improve well-being: Interviews with physicians and health system leaders. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(1), 261–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05381-0

- Feigon, M., Block, C., Guidotti Breting, L., Boxley, L., Dawson, E., & Cobia, D. (2018). Work-life integration in neuropsychology: A review of the existing literature and preliminary recommendations. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 32(2), 300–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2017.1411977

- Gao, Y. N. (2018). Committee representation and Medicare reimbursements-An examination of the resource-based relative value scale. Health Services Research, 53(6), 4353–4370. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12857

- Guiot, A. B., Kirkendall, E. S., Gosdin, C. H., Shah, S. S., DeBlasio, D. J., Meier, K. A., & O’Toole, J. K. (2017). Educational added value unit: Development and testing of a measure for educational activities. Hospital Pediatrics, 7(11), 675–681. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2017-0043

- Hsiao, W. C., Braun, P., Dunn, D. L., Becker, E. R., Yntema, D., Verrilli, D. K., Stamenovic, E., & Chen, S.-P. (1992). An overview of the development and refinement of the resource-based relative value scale: The foundation for reform of U.S. Physician Payment. Medical Care, 30(11), NS1–NS12. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199211001-00001

- Johnson-Greene, D. (2018). Clinical neuropsychology in integrated rehabilitation care teams. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 33(3), 310–318. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acx126

- Kairouz, V. F., Raad, D., Fudyma, J., Curtis, A. B., Schünemann., & Akl E. A. (2014). Assessment of faculty productivity in academic departments of medicine in the United States: A national survey. BMC Medical Education, 14(205), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-14-205

- Katz, S., & Melmed, G. (2016). How relative value units undervalue the cognitive physician visit: A focus on inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 12(4), 240–244.

- Labiner, D. M., Bagic, A. I., Herman, S. T., Fountain, N. B., Walczak, T. S., & Gumnit, R. J. (2010). Essential services, personnel, and facilities in specialized epilepsy centers-revised 2010 guidelines. Epilepsia, 51(11), 2322–2333. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02648.x

- Laugesen, M. J. (2014). The resource-based relative value scale and physician reimbursement policy. Chest, 146(5), 1413–1419. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.13-2367

- Linzer, M., Poplau, S., Babbott, S., Collins, T., Guzman-Corrales, L., Menk, J., Murphy, M. L., & Ovington, K. (2016). Worklife and wellness in academic general internal medicine: Results from a national survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31(9), 1004–1010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3720-4

- Ma, O. J., Hedges, J. R., & Newgard, C. D. (2017). The academic RVU: Ten years developing a metric for and financially incenting academic productivity at Oregon Health & Science University. Academic Medicine, 92(8), 1138–1144. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001570

- Mark, R. E., Klarenbeek, P. L., Rutten, G. J. M., & Sitskoorn, M. M. (2014). Why don’t neurosurgery patients return for neuropsychological follow-up? Predictors for voluntary appointment keeping and reasons for cancellation. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 28(1), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2013.854837

- Maxwell, S., & Zuckerman, S. (2007). Impact of resource-based practice expenses on the medicare physician volume. Health Care Financing Review, 29(2), 65–79.

- NAN. (2001). Definition of a clinical neuropsychologist. Retrieved September 8, 2022, from https://www.nanonline.org/NAN/Files/PAIC/PDFs/NANPositionDefNeuro.pdf

- Nurok, M., & Gewertz, B. (2019). Relative value units and the measurement of physician performance. Journal of the American Medical Association, 322(12), 1139–1140. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.11163

- Petranovich, C., Johnson, A., Smith-Paine, J., Tlustos, S. J., & Baum, K. T. (2023). A survey of pediatric neuropsychologists serving inpatient rehabilitation, Part II: Billing, time allocation and tracking, and professional identity and perceptions. Child Neuropsychology, 29(3), 445–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/09297049.2022.2097652

- Rosenstein, L. D. (2017). Commentary on the use of 96119 in billing for neuropsychological services. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 31(8), 1273–1282. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2017.1329459

- Rosner, M. H., & Falk, R. J. (2020). Understanding work: Moving beyond the RVU. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN, 15(7), 1053–1055. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.12661019

- Satiani, B., Matthews, M. A. B., & Gable, D. (2012). Work effort, productivity, and compensation trends in members of the society for vascular surgery. Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, 46(7), 509–514. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538574412457474

- Sebro, R. (2021). Leveraging the electronic health record to evaluate the validity of the current RVU system for radiologists. Clinical Imaging, 78, 286–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinimag.2021.02.007

- Sogg, S., Lauretti, J., & West-Smith, L. (2016). Recommendations for the presurgical psychosocial evaluation of bariatric surgery patients. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases, 12(4), 731–749.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2016.02.008

- Stites, S., Vansaghi, L., Pingleton, S., Cox, G., & Paolo, A. (2005). Aligning compensation with education: Design and implementation of the Educational Value Unit (EVU) system in an academic internal medicine department. Acad Med, 80(12), 1100–1106. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200512000-00006

- Sweet, J. J., Klipfel, K. M., Nelson, N. W., & Moberg, P. J. (2021). Professional practices, beliefs, and incomes of U.S. neuropsychologists: The AACN, NAN, SCN 2020 practice and “salary survey”. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 35(1), 7–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2020.1849803

- Urwin, J. W., & Emanuel, E. J. (2019). The relative value scale update committee: Time for an update. JAMA, 322(12), 1137–1138. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.14591

- Weidemann, D. K., Ashoor, I. A., Soranno, D. E., Sheth, R., Carter, C., & Brophy, P. D. (2022). Moving the needle toward fair compensation in pediatric nephrology. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 10, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2022.849826

- Zupanc, M. L., Cohen, B. H., Kang, P. B., Mandelbaum, D. E., Mink, J., Mintz, M., Tilton, A., & Trescher, W. (2020). Child neurology in the 21st century. Neurology, 94(2), 75–82. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000008784

Appendix A

Billable Hours Required per Week to Achieve 3000 wRVU Expectation

Neuropsychologist with Psychometrist Support (50% of Evaluations Include Feedback):

Achieving 1500 wRVU with neuropsychological evaluation only:

8.34 wRVU (see for CPT codes billed for each neuropsychological evaluation) equates to 4 hours of billable time

Achieving 1500 wRVU with neuropsychological evaluation and feedback:

8.34 wRVU (see ) + 1.96 (CPT Code 96133) = 10.3 wRVU equates to 5 hours of billable time

Total billable hours to obtain 3000 wRVU expectation:

Neuropsychologist without Psychometrist Support (50% of Evaluations Include Feedback):

Achieving 1500 wRVU with neuropsychological evaluation only:

12.73 wRVU (see for CPT codes billed for each neuropsychological evaluation) equates to 8.5 hours of billable time

Achieving 1500 wRVU with neuropsychological evaluation and feedback:

12.73 wRVU (see ) + 1.96 (CPT Code 96133) = 14.69 wRVU equates to 9.5 hours of billable time

Total billable hours to obtain 3000 wRVU expectation:

Intervention Psychologist (40% 45-minute sessions; 40% 60-minute sessions; 20% intakes):

Achieving 1200 wRVU with 45-minute sessions:

2.24 wRVU (CPT Code 90834) equates to .75 hours of billable time

Achieving 1200 wRVU with 60-minute sessions:

3.31 wRVU (CPT Code 90837) equates to 1 hour of billable time

Achieving 600 wRVU with intake sessions:

3.84 wRVU (CPT Code 90791) equates to 1 hour of billable time

Total billable hours to obtain 3000 wRVU expectation: