Abstract

Purpose: Speech-language pathologists’ (SLPs) role in tracheostomy management is well described internationally. Surveys from Australia and the United Kingdom show high clinical consistency in SLP tracheostomy management, and that practice follows guidelines, research evidence and protocols. Swedish SLPs work with tracheostomised patients, however, the content and extent of this practice, and how it compares to international research is unknown. This study reports how SLPs in Sweden work with tracheostomised patients, investigating (a) the differences and similarities in SLPs tracheostomy management and (b) the facilitators and barriers to tracheostomy management, as reported by SLPs.

Methods: A study-specific, online questionnaire was completed by 28 SLPs who had managed tracheostomised patients during the previous year. This study was conducted in 2018, pre Covid-19 pandemic. The answers were analysed for exploratory descriptive comparison of data. Content analyses were made on answers from open-ended questions.

Results: Swedish SLPs manage tracheostomised patients, both for dysphagia and communication. During this study, the use of protocols and guidelines were limited and SLPs were often not part of a tracheostomy team. Speech-language pathologists reported that the biggest challenges in tracheostomy management were in (a) collaboration with other professionals, (b) unclear roles and (c) self-perceived inexperience. Improved collaboration with other professionals and clearer roles was suggested to facilitate team tracheostomy management.

Conclusions: This study provides insight into SLP tracheostomy management in Sweden, previously uncharted. Results suggest improved collaboration, further education and clinical training as beneficial for a clearer and more involved SLP role in tracheostomy management.

Introduction

Tracheostomy tube placement is one of the most common procedures in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and is performed to facilitate breathing [Citation1]. The most common indications for tracheostomy are (1) acute respiratory failure and need for prolonged mechanical ventilation, (2) neurological insults requiring airway, or mechanical ventilation, or both, and less common (3) upper airway obstruction [Citation2].

The complexity of tracheostomised patients and tracheostomy care requires a range of professional expertise and emerging evidence suggests that optimal tracheostomy management requires a multidisciplinary approach [Citation3–5]. Care by multidisciplinary teams which include speech-language pathologists (SLPs), have been shown to be beneficial for patients. Benefits include decreased total tracheostomy time and increased use of speaking valves, reduced ICU/hospital length of stay and reduced tracheostomy-related complications; however, high-level evidence in some studies is lacking due to methodological issues [Citation5]. Studies have also shown that a multidisciplinary approach and the use of protocols, reduce morbidity and mortality and that dedicated tracheostomy teams enhance the consistency of care, which allows more efficient and effective communication between caregivers [Citation6]. The SLP role in the multidisciplinary team involves communication and dysphagia management (assessment and intervention). Further, SLPs competence of laryngeal function and secretion management is reported to be beneficial in the weaning and decannulation process [Citation3,Citation7,Citation8].

A tracheostomy tube in situ is often associated with dysphagia and impaired airway protection. Whether the tracheostomy tube itself causes impaired swallowing function has been debated. Some studies show that the tracheostomy tube leads to reduced ability to build subglottic air pressure when swallowing with an open tracheostomy tube, reduced glottic closure, desensitization of the larynx, discoordination of swallowing with respiration and reduction of laryngeal elevation [Citation9]. However, other studies have found no significant changes in swallowing or aspiration due to tracheostomy tube [Citation10–12]. Leder et al. [Citation11] reported that the tracheostomy tube may affect swallowing function, but that it is the underlying cause for needing tracheostomy that causes dysphagia and not the tracheostomy in itself. SLPs dysphagia management including bedside FEES can be used to identify risk of aspiration, readiness for cuff deflation and weaning [Citation8,Citation13–15].

A tracheostomy may also negatively impact a person’s ability to communicate. A tracheostomy tube with an inflated cuff causes total loss of voice and is debilitating for oral communication. Communication difficulties have been documented as one of the most negative hospital experiences for patients [Citation16,Citation17]. A study by Laakso et al. [Citation18] showed that ventilated patients struggle in their attempt to achieve effective communication and that health care professionals need to improve their understanding of communication for ventilated patients. The same study also suggested continuous follow-up by SLPs tailoring individual communication solutions.

Research indicates that early, targeted SLP-lead intervention using speaking valves leads to earlier return of voice compared with standard care, i.e. without early speaking valve intervention [Citation5,Citation16,Citation19,Citation20]. This return of voice leads to an improvement in patient-reported cheerfulness and the ability to be understood by others and are also associated with a positive change in quality of life [Citation21]. Aside from restoring voice function, speaking valves have also been reported to decrease tracheal secretions and to improve sense of smell, ability to cough, and weaning trial tolerance [Citation22]. Speaking valves have shown to improve positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), subglottic pressure and restore protective expiration towards the upper airway after swallowing [Citation9,Citation23,Citation24]. For those patients who are unable to tolerate cuff deflation, Above Cuff Vocalisation (ACV) is another possible communication technique. A retrograde flow of gas is directed via the suction port (on those tracheostomy tubes that have an above-cuff suction port), allowing airflow through larynx and thereby enabling voice [Citation25].

The role of SLPs in tracheostomy management is well established and described in several international health care systems, including in both ICU and non-ICU wards [Citation16,Citation26–28]. Surveys reporting on SLPs tracheostomy management in Australia [Citation28] and the United Kingdom [Citation27] show high clinical consistency in tracheostomy management by SLPs and that practice follows guidelines, research evidence and protocols [Citation8,Citation29,Citation30].

In Sweden, approximately 2000 patients undergo a tracheotomy every year [Citation31]. National recommendations for tracheotomy and tracheostomy care in adults were published in 2017, where referral to SLPs is recommended when a swallowing impairment with aspiration is suspected [Citation31], otherwise there is no recommendations or role description in SLP involvement in tracheostomy management. National guidelines for tracheostomy management in children were published in 2018, in which the SLP role and assessments regarding swallowing and communication were described [Citation32]. Currently, there are no specific national guidelines for SLP management of adult tracheostomised patients and no available statistics on number of SLPs working with tracheostomised (paediatric or adult) patients in Sweden [Citation33].

Anecdotal evidence suggests that Swedish SLPs work with tracheostomised patients, however the content and extent of this practice and how it compares to international research is unknown. This study aims to report how Swedish SLPs work with tracheostomised patients, investigating (a) the differences and similarities in SLPs tracheostomy management in Sweden, and (b) the facilitators and barriers to tracheostomy management, as reported by SLPs. Furthermore, this study specifically investigates the following questions; (1) Are there dedicated teams to manage tracheostomised patients? If so, are SLPs a part of these teams? (2) Is there a correlation between the SLPs experience and use of guidelines or protocols?

Methods

Study design

This is an observational, cross-sectional, survey-study using a mixed method design, including quantitative and qualitative outcomes. Non-probability sampling was used for participant selection. Data was collected through a study-specific, online questionnaire, May–June 2018.

Ethics

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki [Citation34]. Ethical approval was obtained by the ethical board at Lund University (VEN, ref nr 27-18). All participants received written information about the study, including that participation was voluntary and answers were confidential. By submitting the questionnaire participants consented to study inclusion. Answers were not traceable back to participants after questionnaire submission.

Data collection and participants

Inclusion criteria were SLPs working in Sweden who, during the past year, had managed tracheostomised patients, children and/or adults. The number of SLPs working with tracheostomy patients in Sweden are believed to be few, though actual figures are unknown. As part of this research a follow-up email survey to the six university hospitals in Sweden identified that although SLPs manage tracheostomised patients, no dedicated SLP positions currently exist in any of the ICUs. To reach as many SLPs as able who work with tracheostomised patients, snowball sampling was used, in which participants were requested to forward the questionnaire link to colleagues and as many suitable candidates as possible. A link to the questionnaire was sent to potential participants through various SLP networks including, but not limited to, regional dysphagia network groups, national SLP tracheostomy working party and SLP-specific communities in social media.

Online questionnaire

A study-specific questionnaire was developed through Survey & Report version 4.3.3.5 [Citation35]. A pilot questionnaire was tested on two SLPs who manage tracheostomised patients, and minor adjustments were made to clarify and improve the questions. The questionnaire consisted of n = 30 questions (see Appendix A). Part I collected demographic data about the participants. Part II consisted of multiple choice and open-ended questions about tracheostomy management. Part III included open-ended questions for the participants to provide further insights into the topic, that is, by describing in their own words how they work with tracheostomised patients. The online questionnaire was distributed via email and online media and was open for 30 days.

Data analysis

Data from the questionnaire were analysed using IBM SPSS version 24 [Citation36]. Descriptive statistics were used for participant demographic data. Non-parametric two-sided tests were used due to sample size and data type. Comparison between participants’ demographic data and research question responses (such as participant tracheostomy experience and use of assessment protocols or use of guidelines) were calculated using Kruskal–Wallis test for ordinal data. Significance level was set to p < .05 for all tests, at 95% confidence level.

For qualitative analyses, Systematic Text Condensation was used to analyse answers from open-ended questions [Citation37]. Answers from questions 25–28 were summarised and presented for each topic. Answers from question 29 and 30 were more comprehensive. Data were analysed initially by the first author who works as a SLP and manages tracheostomised patients predominantly on a neurological ward. Meaning units were identified, coded and sorted into subgroups. Subgroups were thereafter summarised into categories. Bias was minimised for systematic text condensation by using the second author, who does not work with tracheostomised patients and independently analysed this data separately. Comparison between these two analyses were made and led to some adjustments regarding categories. See for comparative analysis process and final themes.

Table 1. Comparison and output content analysis.

Results

Participant demographics

A total of 28 participants from six health care regions (in 10 different Swedish counties, of a total of 21 counties) completed the questionnaire and were included in the analysis. No questions were left unanswered. Demographic data are presented in . The estimated number of tracheostomised patients seen per year ranged widely, from one patient per year up to 80 patients per year, a median of 3,5, (IQR = 8) (range 2–10). Tracheostomised patients were seen in different settings, most commonly in the ICU, in acute settings, rehabilitation and/or within SLP departments. The majority of SLPs worked with adult tracheostomised patients only (79%) and managed both communication and dysphagia (82%). Most participants reported that they had little self-perceived experience with tracheostomy management. Only two reported great experience. These two have also reported that they see 20 respectively 80 patients per year. Analysis using Kruskal–Wallis test showed there was a statistically significant correlation between number of patients seen per year and level of reported experience, H (2) = 7,138, p = .028.

Table 2. Participant demographics.

Communication management

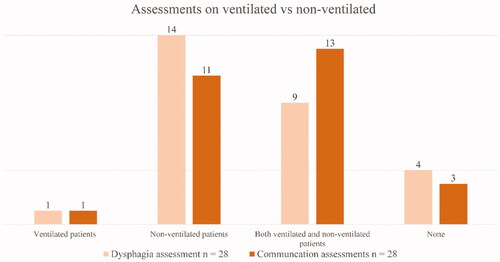

Speech and language pathologists management for communication in ventilated and non-ventilated patients is summarised in . Half of the participants (n = 14) reported assessing communication in ventilated tracheostomised patients. Assessments were made under varying conditions as per . Comments show that assessment was adapted according to patients’ status and whether a speaking valve or cap was preferred by the treating medical team. In this study, use of above cuff vocalisation (ACV) was not used by any of the participants. The most common communication intervention was Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC), and participants also reported management such as information to caregivers and therapy for speech, language and voice impairments.

Table 3. Assessment and management of communication.

Dysphagia management

Regarding dysphagia management, Speech and language pathologists’ management for ventilated and non-ventilated patients is summarised in . Half of the participants (n = 14) conducted dysphagia assessments on non-ventilated patients only, see . A few participants commented that conditions for dysphagia assessments depended on whether patients tolerated speaking valve and or cuff deflation and types of tracheostomy tubes used. A range of evaluation methods were used to assess dysphagia, see ; however, the most commonly used methods were Flexible Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing (FEES) and Clinical Swallowing Examination (CSE).

Table 4. Assessment and management of dysphagia.

Table 5. Access to dysphagia evaluation methods.

Seven out of n = 24 participants responded yes to the question if they were using protocols in their dysphagia assessment. However, examples given were mostly outcome measures such as Functional Oral Intake Scale (FOIS) [Citation38], Penetration Aspiration Scale (PENASP) [Citation39], Secretion Severity Scale [Citation40], EAT-10 [Citation41] as well as several local protocols and one regional protocol. Statistical analysis using Kruskal-Wallis test identified no statistically significant correlation between number of patients seen per year and the use of protocols in dysphagia assessment, H (1) = 0, 592, p = .442.

Tracheostomy management

Results showed that it is most commonly a physician who orders cuff deflation and speaking valve trials on ventilated patients. In two cases, SLPs reported that they lead cuff deflation and speaking valve trials and in one case it was reported that this is nurse-lead. Four participants reported that they did not know who prescribes cuff deflation and speaking valve trials. Results showed that a majority of the participants were not involved in weaning or decannulation and eight (n = 8) respectively nine (n = 9) did not know if the SLP were involved in weaning and decannulation. Only five (n = 5) SLPs reported involvement in the decanullation process. Nine (n = 9) participants reported that there is a dedicated tracheostomy team in their hospital, eight (n = 8) reported no team and n = 11 did not know if there was a team. For reported professions in these teams, see .

Table 6. Reported professions in tracheostomy team.

Only three (n = 3) participants out of n = 28 reported use of guidelines. One respondent referred to the national guidelines regarding tracheostomy management for children. Another participant reported use of guidelines from other countries and one participant used local guidelines. Statistical analysis using Kruskal–Wallis test identifies a statistically significant correlation between number of patients seen per year and the use of tracheostomy specific guidelines, H (1) = 4,41, p = ,036.

Systematic text condensation

All participants answered the open-ended questions. Answers to the open-ended questions, numbers 25–28 (see Appendix A) “Is there anything else you would like to add regarding assessment, intervention, collaboration and patient follow-up?” were generally concise. Responses were sorted into themes, see .

Regarding the theme of Assessment, comments provided thoughts on the need to improve collaboration, to increase SLP involvement in tracheostomy management, and that in-service education was one way to achieve this (n = 2). There were also comments regarding the fact that SLPs were not in charge of decisions regarding speaking valve trials (n = 1). Others commented on available evaluation methods (n = 3) or other tests and protocols (n = 5) used in assessment. Sixteen participants had nothing further to add.

In terms of the Collaboration theme, most comments held examples on partners or carers (n = 10), such as nurses, physicians, physiotherapist but also SLP colleagues in other clinics (n = 3). Joint practice with Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) specialists for FEES (n = 4) and change of tracheostomy tubes were mentioned. Collaborative interventions such as information to other caregivers regarding communication and swallowing were also stated (n = 5). Ten (n = 10) participants had no comments.

Under the theme of Intervention, areas such as AAC trials and training (n = 8), and also swallowing intervention (n = 6), including diet modifications, were identified as regular SLP management. Voice therapy (n = 3), oral motor stimulation (n = 3), resistance breathing (n = 1) and speaking valve training (n = 1) were reported by individual participants. Eleven (n = 11) participants had nothing to add.

Under the final theme of follow-up, different routines and practices were mentioned. Most reported that follow-up was based on patients’ needs (n = 9), though systematic follow-up was routinely performed mostly in the in-patient setting (n = 10). Several participants stated that a new assessment should be conducted after decannulation. Others reported that follow-up only occurred when other caregivers or patients themselves indicated the need of a new assessment (n = 5). Some reported specific routines regarding time, place and content for follow-up (n = 5).

Answers to the open-ended questions number 29 and 30 (see Appendix A) consisted mainly of one or a couple of phrases per participant. After qualitative analysis, the following barriers and facilitators were identified, see .

Barrier 1: Collaboration with other professionals (n = 20)

A majority of participants (n = 20) commented on different difficulties in collaborating with other professionals, regarding communication and joint decisions. A few participants (n = 4) specified that collaboration with other professionals was difficult due to the fact that SLPs were not a part of teams nor present on wards where tracheostomised patients were cared for. Together with a lack of knowledge regarding tracheostomy and influence on swallowing and communication within other professions (n = 5), this lead to a lack of, or late, referrals for SLP assessment (n = 3). Other professions, it was reported, lack an understanding for SLPs prerequisites for assessments. Common ground appeared to be missing for collaboration regarding cuff-deflation, speaking valves and decannulation (n = 5).

Barrier 2: Unclear roles and lack of guidelines (n = 14)

Unclear roles and confusing terminology were reported by several participants (n = 11). Questions regarding who was responsible for what (n = 4) and the lack of guidelines (n = 3) were pointed out. Team collaboration was not clearly organised. Several participants noted that this is a complex patient group (n = 5), often very ill and in need of highly specialised care.

Barrier 3: SLP experience and knowledge (n = 16)

Lack of experience and knowledge regarding this patient group were reported by half of the participants (n = 14). Tracheostomised patients were considered a rare patient group for many SLPs (n = 7) and therefore risk of not maintaining competency was mentioned. Lack of formal training regarding tracheostomy during basic SLP training was also pointed out (n = 1). Some reported an uncertainty in assessments caused by lack of instrumental evaluation methods available (n = 2). Difficulties upholding knowledge regarding different tubes, speaking valves and other materials was also identified as a problematic factor.

Facilitator 1: Improved collaboration with other professionals (n = 14)

Half of the participants suggested improved collaboration as a facilitator for better tracheostomy management (n = 14). Dialogue and close collaboration with physicians and nurses were stated as examples (n = 11). When SLPs were fully involved as part of the team (n = 3), the possibility for the right intervention at the right time increased as one (n = 1) participant stated. Collaboration with the family as an important factor for facilitating tracheostomy management was also mentioned (n = 2).

Facilitator 2: In-service training and education to other professionals (n = 4)

The importance of educating other professionals for deeper understanding for SLP work and recommendations, for example, regarding diet modifications, was suggested by four participants (n = 4). Education or information was also highlighted as important in order to ensure more appropriate and earlier referrals (n = 1).

Facilitator 3: Support from more experienced colleagues (n = 9)

Several participants reported that discussions with more experienced SLP colleagues was of great importance for facilitating tracheostomy management (n = 8). One (n = 1) also suggested that assessment together with other SLP colleagues and access to network groups was beneficial.

Facilitator 4: Adequate prerequisites (n = 8)

Further education for SLPs (n = 3) and more experience is needed (n = 1) for optimising tracheostomy management according to several participants. Some also report the importance of access to adequate evaluation methods (for example FEES/VFSS) (n = 2) and the importance of adequate preparation time before seeing a patient (n = 2).

Discussion

This is the first study to provide insight into tracheostomy management by Swedish SLPs. The similarities and differences in tracheostomy management, as per the first aim of this study, are reported. Results suggest wide variations in terms of number of patients seen per year and work settings, however this study presents valuable information regarding SLPs workload, management and, most importantly, SLPs’ thoughts on facilitators and barriers for optimal tracheostomy management, as per the second aim of this study.

SLP tracheostomy management in Sweden

In the current study, most participants manage both communication and dysphagia in tracheostomised patients, including assessments and interventions, similar to SLP tracheostomy management in the United States, United Kingdom and Australia [Citation26–28]. However, most participating SLPs are not involved in decannulation and none reported to be involved in weaning the patient from the ventilator. This is a clear difference in SLP work practice compared to international studies [Citation26–28]. Baumgartner et al. [Citation26] describe SLP management among tracheostomised patients in the United States and point out that SLPs are often consulted to determine if a patient is suitable for speaking valve trialling. This is in contrast to the current study where AAC-trials were the most common communication intervention. Initial speaking valve trials by SLPs were reported by only a few participants in this study, since it is most often other team members who prescribe and lead speaking valve use. Results from this study also suggest that Swedish SLPs do not use ACV as a communication option as is the case in other countries [Citation25]. These findings highlight that Swedish SLPs are not integrally involved in tracheostomy teams or tracheostomy management to trial different phonation/communication options, nor are they integrally involved in introducing and trialling speaking valves for early communication, swallowing and respiratory rehabilitation, as per multidisciplinary tracheostomy practice elsewhere [Citation3,Citation16,Citation19]. Thirteen participants (n = 13, 46%) reported that they see tracheostomised patients in the ICU likely in a consultancy capacity since current information indicates that SLP positions do not exist within Swedish ICUs.

In the current study, Swedish SLPs are seldom part of a tracheostomy team. This is contrary to evolving literature which establishes that multidisciplinary tracheostomy teams have been shown to optimise tracheostomy care [Citation5,Citation6]. Most remarkable is the fact that a major part of this study’s participants do not know whether or not there is a dedicated tracheostomy team in their workplace. This may reflect a suboptimal structure for tracheostomy care which also was noted in SLP responses. The impact that this may have on patient outcomes has not been investigated in this study. However, as per international practice, it could be anticipated that SLP management would be beneficial for tracheostomy teams to identify risk of aspiration, enhance communicative ability and contribute to determining readiness for decannulation [Citation3]. The current study further suggests suboptimal tracheostomy teamwork, a finding also found in the United Kingdom by McGowan et al. [Citation27]. However, the McGowan study showed high clinical consistency among SLPs and, furthermore, that SLPs have a defined role within the multidisciplinary team, which according to the current study, is lacking in Sweden. This could be influenced by the lack of guidelines and protocols available or used by Swedish SLPs. Unclear roles and/or the lack of national SLP-specific protocols was noted by n = 19 of n = 28 participants. In other countries where SLPs are more involved in tracheostomy management, there are both guidelines and protocols to support this clarified role [Citation27,Citation42,Citation43].

The current study showed strong correlation with self-perceived experience, number of patients seen (H (2) = 7,138, p = .028) and use of guidelines (H (1) = 0, 592, p = .442.). However, only two participants reported self-perceived experience as great and three participants use of guidelines. Statistically, there was no correlation between number of patients seen per year and use of protocols. This is an interesting finding since one would assume that participants with greater experience (e.g. more patients seen per year) would more likely work in a setting with optimised organisational structure for team management and also be using or have better access to established guidelines. Contrary, SLPs with lesser experience would benefit more from protocols to support their clinical practice since the tracheostomised patient group is both complex and rare in their otherwise daily workload. Regardless of SLP level of experience, this study suggests limited use of tracheostomy guidelines or protocols – a difference compared to international practice [Citation27,Citation28]. In places where guidelines are lacking, establishing a tracheostomy team could provide a platform for developing practice guidelines and further implement interprofessional tracheostomy protocols ensuring all patients have the same management and care irrespective ward or location [Citation5,Citation6].

SLP thoughts on facilitators and barriers for tracheostomy management

As for the second aim of this study, participants identified facilitators and barriers for tracheostomy management. The most reported challenge for Swedish SLPs in tracheostomy management is collaboration with other professionals and unclear roles. Participants noted that referrals from wards may be delayed or missed because of unawareness from other professions, including lack of knowledge regarding tracheostomies’ effect on communication and swallowing, what the SLPs role is and how SLPs can contribute to patient care. Similar challenges were found in Ward et al [Citation43] who report that the SLP role in the United Kingdom varied between teams and wards. Critical care wards had a greater awareness of the SLP role and was explained by a higher exposure to tracheostomised patients and therefore a more firmly established role for the SLP. Further, Ward et al. [Citation42,Citation43] recommend that clinicians provide training and education to staff on those wards with less experience of tracheostomised patients, with the aim to improve SLP role recognition.

In terms of facilitators, SLPs in Sweden identified that improved collaboration with other professionals would enable improved tracheostomy management for patients. Similar to the recommendations by Ward et al. [Citation42,Citation43], SLPs in Sweden suggest in-service training for increasing the multidisciplinary team’s awareness of SLPs role and expertise in tracheostomy management, and further to improve collaboration and facilitate more appropriate and earlier referrals. Welton et al. [Citation44] found as a secondary outcome measure that the implementing of a tracheostomy team led to earlier SLP referrals for swallowing assessments. Ward et al. [Citation42,Citation43] also suggest that SLPs not being part of a tracheostomy team is a challenge for clinicians at the international scale which findings from the current study support.

Results from this study indicate that tracheostomised patients are a rare patient group for SLPs in Sweden, which causes difficulties in acquiring experience and maintaining competency. Insufficient formal training and inadequate prerequisites such as preparation time was reported. Similar findings were reported by Ward et al. [Citation42,Citation43] who discussed the complexity of the SLP role in tracheostomised patients and the large variability in amount and type of tracheostomy-specific training received by SLPs in Australia. The need for continuing clinical training and education stated by participants in the current study as a facilitator is similar to issues identified by SLP colleagues in the United Kingdom and Australia.

Another facilitator identified by Swedish SLPs was the support from more experienced colleagues and access to network groups. This seems to be of great importance in facilitating improved tracheostomy management for Swedish SLPs and is also reported by SLPs in Australia and the United Kingdom [Citation42,Citation43]. It is recognised that this is a complex patient group in need of highly specialised care. Specialist knowledge is not expected to be seen in newly examined SLP and according to Ward et al. [Citation42,Citation43] both clinical mentoring and professional development activities are recommended, especially for those who see few tracheostomised patients in their caseloads. This recommendation would also be applicable to Swedish conditions.

Tracheostomy management by Swedish SLPs shows some similarities with SLP practice internationally. However, differences identified are that Swedish SLPs do not have consistency of practice nor established clinical guidelines as per the United Kingdom and Australia. Furthermore, Swedish SLPs are not as involved in tracheostomy care as compared to SLP colleagues internationally specifically in terms of ACV, speaking valve trials, decannulation and weaning input. Of note, however, is that many of the challenges and perceived facilitators identified in the current study, reflect findings from previous international studies, suggesting that SLPs, irrespective of location, face quite similar challenges.

Study limitations

Despite the snowball sampling and SLP recruitment drive, this study’s sample is small (n = 28) and demonstrates a variety in number of patients seen per year and within different work settings. This small sample size may well be representative of current SLP tracheostomy management in Sweden though true representation is not possible since there are no available statistics on number of SLPs working with tracheostomised patients [Citation33]. At the time of the survey, there were no assigned SLPs in ICUs at any University Hospital in Sweden, which differs from international practice [Citation27,Citation28]. Given these above study limitations, results may not be truly representative of the entire population and caution with interpretation and generalisability is warranted.

Also, this study was conducted in 2018, pre Covid-19 pandemic. Since this time, an increase in tracheostomy teams and provision of SLP service into tracheostomy management has been identified in Sweden [Citation45,Citation46]. Further research and study replication would be recommended given this changed and changing environment.

Conclusions

This study shows that Swedish SLPs contribute to tracheostomy management; however, the number of patients seen per year and experience varies widely. Swedish SLPs are often not part of dedicated tracheostomy teams and are not as involved in tracheostomy management as compared to SLPs practicing in the US, Australia and the United Kingdom. SLPs report that the biggest challenges in tracheostomy management are (a) limited collaboration with other professionals, (b) the unclear role of SLPs in tracheostomy management and (c) self-perceived experience. To facilitate optimal tracheostomy management, SLPs suggest better understanding for SLP roles among other professionals, clinical support from colleagues that are more experienced, further education, and improved collaboration with other professionals, preferably in dedicated teams. This study’s results provide an insight into Swedish SLP tracheostomy management previously unchartered. Further research is needed, however this initial report on perceived facilitators and barriers, similar to international literature, suggests a need for further education and clinical training for SLPs to take a clearer and more involved role in tracheostomy management. Moreover, interprofessional education to all team members is further suggested to ensure a greater understanding for roles and responsibilities in the multidisciplinary collaboration for optimal tracheostomy patient care.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sara Wiberg

Sara Wiberg, MSc, registered Speech and Language Pathologist Helsingborg Hospital; clinical lecturer of Speech and Language Pathology at the Department of Logopedics, Phoniatrics and Audiology, Faculty of Medicine, Lund University, Lund, Sweden.

Susanna Whitling

Susanna Whitling, PhD, registered Speech and Language Pathologist, post doctoral researcher and lecturer of Speech and Language Pathology, Department of Logopedics, Phoniatrics and Audiology, Faculty of Medicine, Lund University, Lund, Sweden.

Liza Bergström

Liza Bergström, PhD, registered Speech and Language Pathologist, REMEO, Stockholm; researcher and lecturer, Unit of Speech and Language Pathology, Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden.

References

- Durbin CG. Jr. Tracheostomy: why, when, and how? Respir Care. 2010;55(8):1056–1068.

- Cheung NH, Napolitano LM. Tracheostomy: epidemiology, indications, timing, technique, and outcomes. Respir Care. 2014;59(6):895–915.

- Bonvento B, Wallace S, Lynch J, et al. Role of the multidisciplinary team in the care of the tracheostomy patient. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2017;10:391–398.

- de Mestral C, Iqbal S, Fong N, et al. Impact of a specialized multidisciplinary tracheostomy team on tracheostomy care in critically ill patients. Can J Surg. 2011;54(3):167–172.

- Speed L, Harding KE. Tracheostomy teams reduce total tracheostomy time and increase speaking valve use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crit Care. 2013;28(2):216 e1.

- Mitchell R, Parker V, Giles M. An interprofessional team approach to tracheostomy care: a mixed-method investigation into the mechanisms explaining tracheostomy team effectiveness. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(4):536–542.

- Pryor L, Ward E, Cornwell P, et al. Patterns of return to oral intake and decannulation post-tracheostomy across clinical populations in an acute inpatient setting. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2016;51(5):556–567.

- FICM. Guidance For: Tracheostomy Care https://www.ficm.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-08-tracheostomy_care_guidance_final.pdf. : The Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine; [2020-10-16].

- Suiter DM, McCullough GH, Powell PW. Effects of cuff deflation and one-way tracheostomy speaking valve placement on swallow physiology. Dysphagia. 2003;18(4):284–292.

- Leder SB, Ross DA. Investigation of the causal relationship between tracheotomy and aspiration in the acute care setting. Laryngoscope. 2000;110(4):641–644.

- Leder SB, Joe JK, Ross DA, et al. Presence of a tracheotomy tube and aspiration status in early, postsurgical head and neck cancer patients. Head Neck. 2005;27(9):757–761.

- Goff D, Patterson J. Eating and drinking with an inflated tracheostomy cuff: a systematic review of the aspiration risk. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2018;54(1):30–40.

- Hales PA, Drinnan MJ, Wilson JA. The added value of fibreoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing in tracheostomy weaning. Clin Otolaryngol. 2008;33(4):319–324.

- McGowan SL, Gleeson M, Smith M, et al. A pilot study of fibreoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing in patients with cuffed tracheostomies in neurological intensive care. Neurocrit Care. 2007;6(2):90–93.

- Pryor LN, Ward EC, Cornwell PL, et al. Clinical indicators associated with successful tracheostomy cuff deflation. Aust Crit Care. 2016;29(3):132–137.

- Freeman-Sanderson AL, Togher L, Elkins MR, et al. Return of voice for ventilated tracheostomy patients in ICU: a randomized controlled trial of early-targeted intervention. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(6):1075–1081.

- Magnus VS, Turkington L. Communication interaction in ICU-patient and staff experiences and perceptions. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2006;22(3):167–180.

- Laakso K, Markstrom A, Idvall M, et al. Communication experience of individuals treated with home mechanical ventilation. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2011;46(6):686–699.

- Sutt AL, Fraser JF. Speaking valves as part of standard care with tracheostomized mechanically ventilated patients in intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2015;30(5):1119–1120.

- Sutt AL, Cornwell P, Mullany D, et al. The use of tracheostomy speaking valves in mechanically ventilated patients results in improved communication and does not prolong ventilation time in cardiothoracic intensive care unit patients. J Crit Care. 2015;30(3):491–494.

- Freeman-Sanderson AL, Togher L, Elkins MR, et al. Quality of life improves with return of voice in tracheostomy patients in intensive care: An observational study. J Crit Care. 2016;33:186–191.

- O'Connor LR, Morris NR, Paratz J. Physiological and clinical outcomes associated with use of one-way speaking valves on tracheostomised patients: A systematic review. Heart Lung. 2018;48(4):356–364.

- Prigent H, Lejaille M, Terzi N, et al. Effect of a tracheostomy speaking valve on breathing-swallowing interaction. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(1):85–90.

- Sutt AL, Caruana LR, Dunster KR, et al. Speaking valves in tracheostomised ICU patients weaning off mechanical ventilation–do they facilitate lung recruitment? Crit Care. 2016;20(1):91.

- McGrath B, Lynch J, Wilson M, et al. Above cuff vocalisation: a novel technique for communication in the ventilator-dependent tracheostomy patient. J Intensive Care Soc. 2016;17(1):19–26.

- Baumgartner CA, Bewyer E, Bruner D. Management of communication and swallowing in intensive care: the role of the speech pathologist. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2008; 19(4):433–443.

- McGowan SL, Ward EC, Wall LR, et al. UK survey of clinical consistency in tracheostomy management. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2014;49(1):127–138.

- Ward EJ, Solley C, Cornwell M. P. Clinical consistency in tracheostomy management. J Med Speech-Language Pathol. 2007;15(1):7–26.

- RCSLT. Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists Tracheostomy Competency Framwork https://www.rcslt.org/-/media/Project/RCSLT/tracheostomy-competency-framework.pdf. 2014.

- TRAMS. Tracheostomy Review and Management Service https://tracheostomyteam.org/policies-procedures-1/.

- Nationella rekommendationer för trakeotomi och trakeostomivård LÖF (Landstingens Ömsesidiga Försäkringsbolag); 2017.

- Trakeostomi. Vårdprogram för barn med trakealkanyl. http://www.barnallergisektionen.se/riktlinjer_lungmedicin/trakeostomi.pdf. : Paediatric Allergy Section; 2018.

- http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistics/statisticaldatabase/healthcarepractitioner.: Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare; 2018. [Viewed 4 October 2018].

- Association WM. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191–2194.

- Survey & Report. Växjö, Sweden: Artisan Global Media. 2018.

- IBM Corp. Released 2016. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows., Version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

- Malterud K. Systematic text condensation: a strategy for qualitative analysis. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40(8):795–805.

- Crary MA, Mann GD, Groher ME. Initial psychometric assessment of a functional oral intake scale for dysphagia in stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(8):1516–1520.

- Rosenbek JC, Robbins JA, Roecker EB, et al. A penetration-aspiration scale. Dysphagia. 1996;11(2):93–98.

- Murray J, Langmore SE, Ginsberg S, et al. The significance of accumulated oropharyngeal secretions and swallowing frequency in predicting aspiration. Dysphagia. 1996;11(2):99–103.

- Belafsky PC, Mouadeb DA, Rees CJ, et al. Validity and reliability of the Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10). Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117(12):919–924.

- Ward E, Agius E, Solley M, et al. Preparation, clinical support, and confidence of speech-language pathologists managing clients with a tracheostomy in Australia. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2008;17(3):265–276.

- Ward E, Morgan T, McGowan S, et al. Preparation, clinical support, and confidence of speech-language therapists managing clients with a tracheostomy in the UK. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2012; May-Jun;47(3):322–332.

- Welton C, Morrison M, Catalig M, et al. Can an interprofessional tracheostomy team improve weaning to decannulation times? A quality improvement evaluation. Can J Respir Ther. 2016;52(1):7–11.

- Socialstyrelsen. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/dokument-webb/ovrigt/rehabilitering-slutenvard-covid19.pdf. : Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare; 2020. 10-16].

- SFOHH. https://www.svenskonh.se/sfohh/kunskap-kvalite/covid-19/.: Svensk förening för otorhinolaryngologi, huvud- och halskirurgi; [2020-10-16].

Appendix A

Questionnaire (translated from Swedish)

Part I

1. Do you work as a registered Speech-language pathologist (SLP) in Sweden? (Inclusion criteria)

Yes

No

2. Have you during the last 12 months worked with tracheostomised patients? (Inclusion criteria)

Yes

No

3. In which county do you work? (List of all 21 counties)

4. In which work settings do you manage tracheostomised patients?

Acute setting

Intensive Care Unit (ICU)

Neonatal ward including ICU

Neonatal ICU

Rehab

Paediatrics

General SLP clinic

Habilitation

Specialist unit, team or clinic

Other in-patient clinic

Other out-patient clinic

Other, please specify:

5. Estimate how many tracheostomised patients you have managed in the last 12 months.

6. What experience do you have with tracheostomised patients?

Little

Moderate

Great

7. Which population do you work with?

Children

Adults

Children & Adults

8. What areas do you work with regarding tracheostomised patients?

Dysphagia

Communication

Dysphagia & Communication

Part II

9. Do you perform dysphagia assessment on tracheostomised patients?

Yes, ventilated patients

Yes, non-ventilated patients

No

10. For dysphagia evaluations on ventilated patients, do you assess with

Only inflated cuff

Only deflated cuff

Deflated with speaking valve

Other, please specify:

11. For dysphagia evaluations on non-ventilated patients, do you assess with

Only inflated cuff

Only deflated cuff

Both inflated and deflated cuff

Uncuffed tube

Speaking valve

Cap

Other, please specify:

12. What dysphagia evaluations do you have access to?

Fibreoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing (FEES)

Video Fluoroscopic Swallowing Study (VFSS)

Clinical Swallowing Examination (CSE)

CSE with Modified Evans Blue Dye Test (MEBDT)

CSE with Cervical Auscultation (CA)

CSE with pulse oximetry

Other, please specify:

13. Do you use any protocols in your dysphagia assessment?

Yes

No

14. If yes, specify what protocols you use

15. Do you perform communication assessments on tracheostomised patients?

Yes, ventilated patients

Yes, non-ventilated patients

No

16. What kind of communication intervention do you provide?

Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC)

Speaking valve trial

Other, please specify:

17. For communication assessments on ventilated patients, do you assess with

Only inflated cuff

Only deflated cuff

Deflated cuff with speaking valve

Other, please specify:

18. For communication assessments on non-ventilated patients, do you assess with

Cuffed tube, only inflated

Cuffed tube, only deflated

Cuffed tube, both inflated and deflated

Speaking valve

Cap

Other, please specify:

19. Who orders deflation and speaking valve on ventilated patients?

Physicians

SLPs

Nurse

Other, please specify:

Don’t know

20. Are SLPs involved in weaning from ventilator?

Yes

No

Don’t know

21. Are SLPs involved in decannulation?

Yes

No

Don’t know

22. Do you use any guidelines in SLP tracheostomy management?

Yes

No

If yes, please specify

23. Is there a dedicated tracheostomy team in the hospital you work in?

Yes

No

Don’t know

24. If yes, what professions are part of this team?

Occupational therapist

Dietician

Physiotherapist

Social worker

Speech-language pathologist

Physician

Registered nurse

Enrolled nurse

Other, please specify:

25. Excluding current answers – is there anything else you do regarding assessment?

26. Excluding current answers – is there anything else you do regarding intervention?

27. Excluding current answers – is there anything else you do regarding collaboration?

28. How do you manage tracheostomised patients regarding follow-up?

Part III

29. What challenges do you experience with SLP tracheostomy management?

30. What facilitators are there to SLP tracheostomy management?