Abstract

Aim

Students with hearing loss (HL) often fall behind hearing peers in complex language tasks such as narrative writing. This study explored the effects of school grade, gender, cognitive and linguistic predisposition and audiological factors on narrative text quality in this target group.

Method

Eleven students with HL in Grades 5–6 and 7–8 (age 12–15) who took part in a writing intervention wrote four narrative texts over six months. A trained panel rated text quality. The effects of the students’ working memory capacity, language comprehension, reading comprehension, school grade and gender and the intervention were analyzed as a mixed-effects regression model. Audiological factors were considered separately.

Results

The analysis showed that throughout the period, texts written by female students in Grade 7–8 received the highest text quality ratings, while those written by male students in Grade 7–8 received the lowest ratings. There was no effect of the intervention, or of the linguistic and cognitive measures. The students with the lowest text quality ratings received amplification later than those with high ratings, but HL severity was not associated with text quality.

Conclusion

Hearing loss severity was not a decisive factor in narrative text quality. The intervention which the students took part in is potentially effective, with some adaptation to the special needs of students with HL. The strong gender effects are discussed.

Introduction

In spite of substantial pedagogical, technical and medical advances in the field, many students with hearing loss (HL) lag behind peers with normal hearing (NH) in complex language skills, notably reading and writing [Citation1–3]. This may be due to slow development of language skills such as spoken language comprehension, reading comprehension and spoken narration, all essential for the development of writing skills. It is not surprising then that students with HL do not reach the goals stated in school curriculum to the same extent as students with NH [Citation4]. Only 10–15% of Swedish high school graduates with HL proceed to higher education, compared to around 60% of graduates with NH [Citation5,Citation6].

The present study focuses on writing skills in students with HL in Sweden. References to grades and learning goals apply to the Swedish school system and curriculum. One writing skill that is part of the school curriculum is the production of narrative texts. Early establishment of a narrative structure is essential for academic success [Citation7–10]. Moreover, being able to produce a written narrative is a prerequisite for the development of other genres, such as expository or argumentative texts [Citation8]. In spoken language, the narrative structure is well-established in six-year-olds with typical language development [Citation11]. At the age of nine, children generally have access to the schema of a well-formed personal narrative [Citation12–14]. They know that it consists of an introduction, a sequence of events and an ending, and a description of the characters. The curriculum states that knowledge of the narrative structure should be established by the end of Grade 3, when children are nine to ten years of age [Citation15]. It is however not specified to what extent students should be able to demonstrate this knowledge in written narratives [Citation15]. The curriculum furthermore states that students from Grades 4–9 (age 10–16), should expand their writing skills to other genres, process and revise their text, learn to give and receive feedback, write by hand and on the computer, and learn to organize and edit a text [Citation15]. In addition, they should learn to correctly use subordinate clauses, parts-of-speech, morphology, spelling rules, punctuation, and text cohesion [Citation15]. Further, they should learn which features, such as content and lexicon, are typical for different genres [Citation15]. In other words, the processes involved in writing are demanding, even for writers with fundamental transcription skills [Citation16]. Swedish female students reach the curriculum goals to a greater extent than male students do [Citation17]. This is corroborated by for instance Kanaris [Citation18] who noticed that girls often are good writers and boys are under-achievers. Similarly, Myhill [Citation19] reported that 8- to 10-year-old girls’ texts were comparatively longer and more complex, and focused more on description and elaboration than boys’ texts.

At present, it is unclear how the curricular goals in writing may be obtained, despite recent meta-analyses of writing intervention [Citation20]. Neither the curriculum nor the teacher training specifies what type of writing instruction should be used, whether for students with NH or HL. Teachers and schools are free to choose their own methods of instruction. The effects of HL on narrative writing are not clearly identified. One reason for this is the heterogeneity in audiological, cognitive and linguistic predispositions in students with HL, and the complex relationships between these variables. Approximately 20–30% of all school children with HL have language learning problems comparable to those of children with NH diagnosed with a developmental language disorder [Citation21,Citation22]. The degree of HL is one relevant factor in this, but, at the same time, it is seldomly proportional to the severity of language learning difficulties. This suggests that cognitive and linguistic factors need to be taken into consideration to explain why certain students with HL perform better than others. For instance, cognitive resources are particularly taxed by a degraded speech signal due to noise, speaker’s voice or poor amplification. Thus, students with HL have less resources left for a school task [Citation23]. There is ample evidence that working memory plays a crucial role in writing [Citation24,Citation25]. The writer of a narrative text must recall what happened, plan and organize the events, make lexical choices, formulate sentences correctly and at the same time think about a range of formal aspects like spelling and punctuation. The comprehension of spoken language has been associated with spoken narrative skills as well as with reading comprehension and school performance [Citation7,Citation26] in students with NH. Reading comprehension and working memory capacity have been shown to be associated with each other in students with HL [Citation27,Citation28].

Research on writing in students with HL is scarce. Some aspects of written narratives were studied in 11- to 19-year-old students with HL and controls with NH [Citation29]. The students with HL wrote fewer complex sentences and used fewer function words, but they were not significantly different from a control group in spelling accuracy. Students with HL had to allocate most of their cognitive resources to language processing and did not have sufficient resources available for the organisational and formal aspects of a text, the authors concluded [Citation29]. Only a few documented and evidence-based writing intervention models are available for this target group. Strassman and Schirmer [Citation30] reviewed teaching practices for students with HL and found that methods for teaching writing fell into four categories: teaching the writing process itself, looking at properties of finished texts, writing to facilitate content learning, and feedback on writing. There was, however, no clear evidence of effects [Citation30]. More recently, it has been suggested that a combination of three elements (i.e. strategy instruction, teacher–student dialogue, and teaching language skills and metalinguistic awareness) improves writing in students with HL [Citation31,Citation32]. One intervention method which includes some of these elements and that others found effective for improving writing [Citation20] is observational learning, which has been found to boost writing in students with NH [Citation33–37].

To summarize, the ability to produce a written narrative is a prerequisite for the production of other text genres and for academic achievement. The results from previous studies of texts written by students with NH suggest that girls are better writers than boys. There is a lack of research on associations between HL and narrative writing. One reason is the large heterogeneity among students with HL. Another is the complicated interaction of HL with other linguistic and cognitive predispositions which may also influence text writing. Finally, neither writing skills in students with HL nor methods for teaching writing for these students have been studied extensively. With this in mind, the current study was carried out.

The present study

The aim of the present study is to identify possible predictors of narrative text writing in students with HL. Eleven students from two school classes, Grades 5–6 and 7–8, with varying HL severity wrote four texts which were graded by a rater panel. The students’ cognitive and linguistic predispositions (i.e. working memory capacity, language comprehension, and reading comprehension) were assessed, and data on audiological factors were collected. The present study is part of a comprehensive study in which students with NH and students with HL followed the same writing intervention [Citation36].

The analysis is guided by the following questions:

What are the effects of working memory capacity, language comprehension, reading comprehension, school grade and gender on narrative text quality in students with HL?

What associations are there between degree of HL and age at amplification and text quality?

Is observational learning suitable for the training of narrative text writing in students with HL?

Method

Students

Head teachers and teachers of classes exclusively for students with HL were contacted. In two classes, one a combined Grades 5–6 and the other a combined 7–8, the teachers accepted to participate. The students and teachers in the classes communicated with spoken language sometimes supported with sign language. The classrooms were equipped with hearing loops (FM system) with microphones for students and teachers. The students followed the same curriculum as NH students. The total number of students in the two classes was 19. No student was a priori excluded. Six students chose not to participate in the study, but were nevertheless present during the data collection, as recommended by the Regional Ethical Review Board. Data from these students were discarded. In addition, two students missed two or more intervention lessons and their data were also excluded from analysis. Thus, the results of 11 students (5 girls and 6 boys) were used for this study. provides an overview of the group.

Table 1. Student overview.

The students in Grade 5–6 were between 12;5 and 13;8 years old, and those in Grade 7–8 between 13;4 and 15;3 years old. The parents of ten students provided information about what (spoken or signed) languages were used at home, and some audiological data of their children. Additionally, audiological records of nine students were consulted, with the consent of the parents. There was thus considerable variation in the detail of available audiological data. For most students, data on better ear hearing level (BEHL) and type of amplification was obtained. The students’ degree of HL had been categorized according to the classification by [Citation38]. This means that a mild HL constitutes a BEHL of 20–40 dB, moderate, 40–70 dB, severe, 71–90, and a profound HL constitutes a BEHL over 90 dB. Two students had unilateral HL with severe HL on the afflicted ear, while the remaining nine had bilateral HL varying from mild to profound. The age at diagnosis varied from three months to ten years. One student had no amplification. The other students had one or two hearing aids (HA) or bimodal amplification, i.e. one HA and one cochlear implant (CI). Ten students spoke Swedish as their first language and one had another European spoken first language. Some students were exposed to one or more additional spoken languages or sign language, as well as signing as a form of alternative and augmentative communication.

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of The Swedish Ethical Review Authority and the protocol was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund (Dnr. 2013/270). The parents and students gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Narrative texts and text quality ratings

The students’ writing performance was assessed four times: one week before and one week after the writing intervention (see below), after another six weeks, and once more after the summer vacation five months later. The same time intervals between the first three texts were also used by Grenner et al. [Citation36]. The topics of the four texts were, respectively: 1) Write about a time when you were saved from a jam, or when you saved someone else from a jam; 2) Write about a time when you were hurt; 3) Write about a time when you were afraid; 4) Write about a time when you made somebody happy. These topics have also been used in previous studies and found suitable for the age group [Citation14,Citation36,Citation39]. The students wrote the texts on a laptop using ScriptLog [Citation40], a keystroke logging program with a basic word processing interface. The topic for the narratives was written on a slide in the classroom and were also read aloud to the students. At each time, the students had 30 min for writing.

The quality of the texts was subsequently rated by a panel of six raters with a method validated by [Citation41] and used in comparable studies of writing [Citation36,Citation42]. Before the start of the rating procedure, the raters were shown several benchmark texts on the same topics with quality ratings marked on a 100-mm visual analogue scale, together with a motivation why each text received a specific rating. The rating was holistic, but based on structure and organization, content, grammar and spelling. In the rating procedure, each text was rated in the same way by three of the six raters, yielding three scores for each text that could range from 0 to 100. The raters were unaware of the order in which the texts had been written and they were not informed that the texts had been written by students with HL or that each student had written several texts. Interrater reliability was calculated on a larger dataset including the texts in the present study and other texts on the same topics and was found high (Cronbach’s alpha .90). More details on the rating procedure are provided in [Citation36].

Cognitive and linguistic tasks

The students were given norm-referenced or standardized tests of verbal working memory capacity [Citation43], language comprehension [Citation44] and reading comprehension [Citation45]. For practical reasons, the tests of working memory capacity and language comprehension were administered after the first text was written, while reading comprehension was tested after the second text was written. All tests were administered by the researchers in the classroom in the absence of the teachers.

Working memory capacity was assessed with a 36-items subset from a classroom screening test [Citation43]. The items were pre-recorded and were presented to the students via the hearing loop. The working memory test has a process component (general knowledge yes/no-questions), and a recall component (remembering letters). As an example, the students heard the letter “B” and were asked “Is France larger than Denmark?”. They responded by holding up a YES or a NO sign. Then they would hear the letter “J” and were asked “Is a bird a mammal?”. Again they held up a YES or NO sign, and wrote down the two letters, in the right order. The average for students with NH in Grade 5 is 31.7 (SD 5.9) and 32.9 (SD 4.9) for students in Grade 7. Language (listening) comprehension was measured with the Test for Reception of Grammar–2, adapted for Swedish [Citation44]. This test consists of 80 spoken sentences that each needs to be matched with one of four pictures. The sentences are divided into 20 blocks of four sentences which are scored as correct if all responses within a block are correct. This yields a possible maximum score of 20, and the expected score for normal-hearing students is approximately 17 for grade 5 and 18 for grade 7. In the present study, a research assistant read each sentence aloud, using a microphone connected to the hearing loop. The pictures were projected on a screen, and the students marked the matching picture in a booklet. Reading comprehension, finally, was assessed using the SL40 [Citation45]. In this test, the student reads one sentence at a time and chooses a corresponding picture. The maximum score is 40 points, and normal-hearing students in grade 5 normally have a score of at least 38 items correct. Older students are expected to score all items correct.

An overview of the scores on the three tests is displayed in . Seven students had scores on the working memory test which were higher than or equal to the reference value [Citation43]. The scores of the remaining four, though, were well below this value. The average score from the Grade 7–8 students was not higher than that from the Grade 5–6 students. There was a slight tendency that the boys had higher scores than the girls. All scores from the students in Grade 5–6 were below the age norms for students with NH on the language comprehension test, while three out of the six students in Grade 7–8 had scores which were below the age norms [Citation44]. This suggests that the level of language comprehension was, relatively speaking, somewhat less behind in the higher grade than in the lower grade. Five students had scores below the 10th percentile which is a common cut-off for language disorder. The average score of the Grade 5–6 students was slightly below that of the Grade 7–8 students. Only four students had a score on the reading comprehension test of 38 or more, i.e. the norms of fifth-grade students with NH [Citation45].

Writing intervention

The students took part in a writing intervention based on observational learning [Citation36]. In observational learning, learners watch films of models (usually peers) who perform and comment upon a writing task [Citation35]. In this way, observation and reflection are separated from writing and practice [Citation35]. As a consequence, learners do not have to draw on cognitive resources while simultaneously performing the target skill. The paradigm has been found to have a positive effect on writing skills [Citation33–37]. In a recent study, 55 students with NH from Grade 5 took part in the lessons. A modest but significant increase in text quality was found after the intervention, and this effect was somewhat more pronounced in students with relatively low language comprehension scores [Citation36]. In the present study, five 40 min lessons were given during three consecutive weeks. Each lesson focused mainly on one aspect of narrative writing, targeted in the curriculum [Citation15]. See [Citation36] for a description of the content and the execution of the lessons.

Analyses

Various mixed effects models were used to estimate the effects of six predictors: time of measurement (four texts), Grade (5–6 or 7–8), gender, working memory, language comprehension and reading comprehension. Interaction effects between time of measurement and the remaining measures were also considered. Models were compared on the basis of AIC values. The computations were done in R version 3.5.3 [Citation46], using the package lme4 [Citation47]. The degree of HL was not used as a predictor in the statistical analysis as the information was missing for some students. The effects of HL will be presented and discussed separately.

Results

One student only wrote three texts and one other text was not rated. Consequently, 126 quality ratings of 42 texts were collected and used for data analysis. The individual quality ratings for each text are shown in . The average ratings for each text varied from 13 to 77 suggesting large differences in writing skills among the students. Across the four texts, the ratings within each student were relatively consistent, which suggest a constant performance not affected by the writing intervention or general development to the follow-up the next semester. The texts written by the Grade 7–8 students received on average considerably higher ratings (10–16 points) than those written by the Grade 5–6 students. The values in show that most students were given a lower score on Text 2 than on Text 1.

Table 2. Individual text quality ratings.

Several regression models with different groupings of the six predictors (text, grade, gender, working memory, language comprehension and reading comprehension) were evaluated. The predictor Text was never excluded from these models, but any of the other five predictors could be used to see if the exclusion of this predictor made the model fit significantly worse or not. The list included models with only main effects as well as models with two-way interactions between the predictors. An overview of the models that were compared is given in Appendix, with the chosen model indicated in boldface. The random effects in all models were random intercepts for students and for raters. Repeated contrasts were applied to the Text predictor, so that the coefficients represented the successive differences over time, between texts 1 and 2, 2 and 3, 3 and 4. The continuous predictors (i.e. working memory, language comprehension and reading comprehension) were centered at these variables’ median values in order to enhance the interpretability of the regression outcome. The effects of these three variables, however, were not significant in any of the models that were tested. The model that was chosen among those that were evaluated contained the predictors Text, gender, and grade, including interactions of Text and gender and of grade and gender. These two-way interactions were both statistically significant, and this model had a lower AIC value than any of the other considered models had. The output of this model is shown in .

Table 3. Regression output.

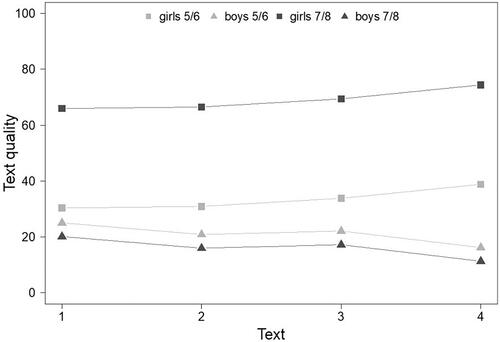

The estimate, labeled “Intercept,” is the overall estimated text quality of Text 1 for a female student in Grade 5–6. The value is just above 33 points. The next three lines indicate how text quality changes for Grade 5–6 female students with slight but non-significant increases across the four texts. The following two rows describe the effect of gender and grade on text quality. Boys from Grade 5–6 wrote texts that were rated 12 points lower than girls’ texts from the same grade. The girls in Grade 7–8 had an estimated 36 points higher text quality rating than the girls from Grade 5–6. The next three lines indicate how the differences between the four texts written by the boys differ from those written by the girls. The boys differ significantly from the girls on the rating of text four, which received low ratings. The last row in the table shows the interaction between gender and school grade. The boys from Grade 7–8 wrote texts that were actually rated lower than the texts written by the boys from Grade 5–6. shows the predicted text quality of girls and boys in Grades 5–6 and 7–8 for each text. It shows that group differences were larger than any effects over time. Both lines representing girls increase over time, whereas the lines representing boys decrease, most notably to Text 4, which was written after the summer vacation.

In sum, the quality of the texts written by girls increased slightly but non-significantly across the four texts, and was significantly better than the quality of texts written by boys (approximately 12 points for the students in Grade 5–6, and 40 points for the students in Grade 7–8). The quality of boys’ texts did not increase over time. On the contrary their text quality decreased (approximately 5 points). In addition, there was a grade effect, but this effect was only significant for girls (approximately 35 points), and not for boys (approximately 5 points).

Audiological factors

The considerable heterogeneity of the audiological factors motivated the following inspection of individual results for students with the highest and the lowest text quality. The three students with the highest average text quality ratings were all girls in Grade 7–8. The first of these three (case 6) was a student who was diagnosed with profound HL when she was a few months old and did not receive HA until 17 months later. At the time of the study, she was bimodally aided with a CI and a HA. In spite of the profound HL, language comprehension was comparable to norms for students with NH, but working memory and reading comprehension were not. The second student (case 7) had a bilateral severe HL for which she was bimodally aided and she was diagnosed at age three. Her reading comprehension, language comprehension and working memory results were limited compared to norms. The third student (case 8) had a moderate HL and was diagnosed at four years old after which she immediately received bilateral HA. She had adequate results on working memory and language comprehension, but low reading comprehension results. In sum, none of the three students with the best text quality was diagnosed early or received amplification early – the earliest at age one and the latest at age four. All three were girls in Grade 7–8, and their results on the working memory test and language and reading comprehension tests varied.

The three students who received the lowest average text quality ratings were a boy in Grade 5–6 (case 4) and two boys in Grade 7–8 (cases 9 and 11). The boy in Grade 5–6 was diagnosed with a HL (of unknown degree to the authors) at six years of age. He received bilateral HA directly after diagnosis. One boy in Grade 7–8 (case 9) had a moderate HL. He was diagnosed at age five and amplified bilaterally with HA at age six. The other boy in Grade 7–8 (case 11) had a moderate HL and was diagnosed at age 10. In sum, the three students with the lowest text quality ratings were amplified very late. Two of these students had limited language comprehension (below the 10th percentile) and limited reading comprehension, and one of them had low scores on the working memory capacity test. From this, no clear relation between degree of HL and narrative writing skills is apparent. In fact, the three students with the highest ratings had more severe HL than at least two of the students with the lowest ratings. The students who had the lowest text quality ratings were, however, amplified considerably later than the students with the highest text quality ratings.

Discussion

In the present study, possible predictors of narrative text quality in students with HL were investigated over the course of four written narratives and a writing intervention. The results showed effects of gender and grade but not of working memory, reading comprehension, or spoken language comprehension. Nor did text quality ratings change after the intervention. Studies on students with HL all emphasize the great heterogeneity of the population [Citation1,Citation48,Citation49]. The present study is no exception. The individual variability between students in the sample of 11 students was considerable. Results on the formally assessed linguistic and cognitive tests differed considerably. The students had exposure to one or more spoken languages or to spoken and signed language. Hearing sensitivity and time factors (degree of HL, age at diagnosis and age at amplification) also varied greatly. The students were born before neonatal hearing screening had been implemented in Sweden. Age at diagnosis and amplification was thus late for a majority of them. Consequently, listening abilities had been challenged for these students for a long time, by degraded speech signals and limited language skills, which may have affected language comprehension and learning adversely [Citation23].

The regression model did not indicate changes in text quality ratings over time, but there were interaction effects showing that the text quality was significantly lower in the boys’ texts than the girls’, and that the text quality of the boys’ texts was significantly lower at the fourth text. The fourth text was written a month into the semester after the summer vacation. One possible explanation is the “summer loss” in academic results. In a review by Cooper et al. [Citation50], the authors found evidence of setbacks of up to one month after the summer vacation in some studies, and gender differences were found inconclusive between studies. A recent study [Citation51] showed that 6- to 9-year-old students with NH may be set back in semantic verbal vocabulary fluency after the nine-week long summer vacation, but had regained that loss by the end of the fall semester. The decrease in text quality ratings for boys’ texts at the follow-up text after summer vacation in the present study suggests that boys may be more affected by a summer loss than girls.

The three students who had the highest text quality ratings were all girls in Grade 7–8. While the effect of working memory was not significant in the statistical analysis, it is striking that among the three students with high text quality ratings were two students with low results on the working memory test. Two of the three students received the highest results of the eleven students on the reading comprehension test. Reading comprehension and narrative skills are associated [Citation52], and these results also suggest that reading comprehension is an important factor to take into consideration in studies of narrative writing. Further, good reading comprehension during writing requires automatized reading processes, leaving more capacity for higher level processes of writing.

The observed gender differences are consistent with previous findings that girls outperform boys in narrative text writing [Citation18,Citation19,Citation36]. The three students with the lowest average text quality ratings were three boys, one in Grade 5–6 and two in Grade 7–8. Two had language comprehension below the 10th percentile compared to reference values on the test, a common cut-off for language disorder. One also had low results on the working memory test, and all three had low results on the reading comprehension test. Poor spoken language comprehension has been indicated as an early predictor of developmental language disorders in children with NH [Citation53,Citation54]. In addition, the students in the present study may not have received optimal audiological intervention, with a late diagnosis of HL and lack of proper amplification. Although the three students with the highest text quality were not amplified early, at 1, 3, and 4 years old, they were all amplified considerably earlier than the students with the lowest text quality, who received their HA at 6, 6, and 10 years old. This may have played a role for the development of language skills of the students. Early identification and intervention are crucial for language development [Citation1,Citation23,Citation55].

An unexpected finding was that the boys’ texts from the higher grade did not receive higher quality ratings (in fact, even somewhat lower) than the boys from the lower grade. A possible interpretation is that students with HL who perform well in classes for students with HL may move to mainstream schools between grades 6 and 7, when many students change schools, or that students struggling in mainstream schools move to classes for students with HL [Citation56]. Another possible interpretation is that the writing teaching strategies in the higher grade were geared more towards girls than towards boys. However, in the absence of more precise information on what these strategies were, this conclusion is very tentative and may be addressed in future studies.

The students in the present study responded well to the writing intervention, even though this did not result in noticeable improvements in text quality ratings. Some aspects of the writing intervention may be suitable for students with HL. When listening is challenged, as it is in students with HL, a clear and recurrent structure (observation, reflection and learning) could support listening and thus the comprehension of instructions. Further, the “film peers” could be simultaneously seen, heard and read (by subtitles), and even reiterated, which may relieve the students’ listening effort. On the other hand, the relatively implicit nature of observational learning may prove to be too abstract for students with HL, as their linguistic and cognitive skills are often not on par with those of age peers with NH. It may be supplemented with, for instance, individual feedback on students’ written texts with reference to the themes addressed during the lessons or other explicit writing instruction. It may pose a challenge to design an intervention long enough to be effective, but short enough to fit into one semester and to spare time for other curricular goals.

Conclusions

In the present study, possible predictors of narrative writing skills in students with HL were explored. Girls wrote better texts than boys, and school grade had a positive effect on texts written by girls but not on texts written by boys. Instead, a “summer loss” was observed in texts written by boys but not by girls. Age at amplification seemed more important for text quality than severity of HL. There were no statistically significant effects of the students’ working memory, language comprehension, or reading comprehension on text quality. The absence of effects of these predictors may have been due to limitations in sample size which inevitably reduced statistical power in the study. For that reason, these conclusions are tentative at present. Finally, the writing intervention in the context of which the data were collected is a promising paradigm but should be further adapted to the special needs of students with HL.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Emily Grenner

Emily Grenner is a speech-language therapist and PhD student at the Department of Clinical Sciences, Logopedics, Phoniatrics and Audiology, Lund University, Sweden. Her PhD studies concern processes and products of narrative writing in school children with normal hearing and school children with hearing loss.

Joost van de Weijer

Joost van de Weijer is Associate Professor in Linguistics at the Centre for Languages and Literature at Lund University. His research focuses on the perception of foreign-accented speech. He is also affiliated as methodologist with the Lund University Humanities Lab, where he mainly works with the analysis of experimental data.

Victoria Johansson

Victoria Johansson is Associate Professor in Linguistics at the Centre for Languages and Literature and Deputy Director at the Lund University Humanities Lab, Lund University, Sweden. Her research focus is on language development through the lifespan, primarily cognitive aspects of writing.

Birgitta Sahlén

Birgitta Sahlén is Professor in Speech Pathology at the Department of Clinical Sciences, Logopedics, Phoniatrics and Audiology, Lund University, Sweden. Her research focus is on cognition and communication in children with language disorder and/or hearing loss. comprehension, listening effort, motivation and learning in relation to children’s cognitive capacity. She is currently heading comprehensive intervention projects aiming at improving children’s narrative writing by observational learning, and teachers’ communicative techniques for language learning interaction in the classroom.

References

- Geers AE, Nicholas J, Tobey E, et al. Persistent language delay versus late language emergence in children with early cochlear implantation. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2016;59:155–170.

- Sandgren O, Hansson K, Sahlén B. Working memory and referential communication-multimodal aspects of interaction between children with sensorineural hearing impairment and normal hearing peers. Front Psychol. 2015;6:242.

- Sahlén B, Hansson K, Lyberg-Åhlander V, et al. Spoken language and language impairment in deaf and hard-of-hearing children: fostering classroom environments for mainstreamed children. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 2018.

- SOU. Samordning, ansvar och kommunikation – vägen till ökad kvalitet i utbildningen för elever med vissa funktionsnedsättningar (Coordination and responsibility – increased quality in education for students with certain disabilities). Stockholm: Wolters-Kluwer; 2016. 46.

- HRF. Årsrapport [Yearly report]. 2007.

- SCB. Årsrapport [Yearly report]. 2015.

- Reuterskiöld C, Hansson K, Sahlén B. Narrative skills in Swedish children with language impairment. J Commun Disord. 2011;44:733–744.

- Feagans L, Appelbaum MI. Validation of language subtypes in learning disabled children. J Educ Psychol. 1986;78:358–364.

- Catts HW, Hogan TP, Fey ME. Subgrouping poor readers on the basis of individual differences in reading-related abilities. J Learn Disabil. 2003;36:151–164.

- Griffin TM, Hemphill L, Camp L, et al. Oral discourse in the preschool years and later literacy skills. First Language. 2004;24:123–147.

- Karmiloff-Smith A. The grammatical marking of thematic structure in the development of language production. In: Deutsch W, editor. The child’s conception of language. London (UK): Academic Press; 1981. p. 121–147.

- Berman RA, Slobin DI. Relating events in narrative: a crosslinguistic developmental study. Hillsdale (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, New York (NY): Psychology Press; 1994.

- Nordqvist Palviainen Å. Speech about speech: a developmental study on form and function of direct and indirect speech [Theses]. Göteborg; 2001.

- Strömqvist S. Discourse flow and linguistic information structuring: explorations in speech and writing. Göteborg: Univ.; 1996. (Gothenburg papers in theoretical linguistics: 78).

- Skolverket. Läroplan för grundskolan, förskoleklassen och fritidshemmet (Curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool class and school-age educare). 2011. revised 2019 ed. 2019.

- Bourdin B, Fayol M. Even in adults, written production is still more costly than oral production. Int J Psychol. 2002;37:219–227.

- Skolverket. Slutbetyg i grundskolan våren 2019:1342. [Board of education, final grades of the compulsory school, spring. 2019].

- Kanaris A. Gendered journeys: children’s writing and the construction of gender. Lang Educ. 1999;13:254–268.

- Myhill D. Towards a linguistic model of sentence development in writing. Lang Educ. 2008;22:271–288.

- Graham S, Harris KR. Evidence-based writing practices: a meta-analysis of existing meta-analyses. In: Redondo RF, Harris K, Braaksma M, editors. Design principles for teaching effective writing: theoretical and empirical grounded principles. Vol. 34, Studies in writing. Leiden (the Netherlands): Brill Academic Publishers; 2018. p. 33–37.

- Briscoe J, Bishop DVM, Norbury CF. Phonological processing, language, and literacy: a comparison of children with mild-to-moderate sensorineural hearing loss and those with specific language impairment. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2001;42:329–340.

- Geers AE, Moog JS, Biedenstein J, et al. Spoken language scores of children using cochlear implants compared to hearing age-mates at school entry. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2009;14:371–385.

- Mattys SL, Davis MH, Bradlow AR, et al. Speech recognition in adverse conditions: a review. Lang Cogn Process. 2012;27:953–978.

- McCutchen D. Knowledge, processing, and working memory: implications for a theory of writing. Educ Psychol. 2000;35:13–23.

- McCutchen D. From novice to expert: implications of language skills and writing-relevant knowledge for memory during the development of writing. J Writ Res. 2011;3:51–68.

- Blom E, Boerma T. Why do children with language impairment have difficulties with narrative macrostructure? Res Dev Disabil. 2016;55:301–311.

- Torkildsen JK, Arciuli J, Haukedal CL, et al. Does a lack of auditory experience affect sequential learning? Cognition. 2018;170:123–129.

- Sahlén B, Hansson K, Ibertsson T, et al. Reading in children of primary school age – a comparative study of children with hearing impairment and children with specific language impairment. Acta Neuropsychol. 2004;2:393.

- Asker-Árnason L, Åkerlund V, Skoglund C, et al. Spoken and written narratives in Swedish children and adolescents with hearing impairment. Commun Disord Q. 2012;33:131–145.

- Strassman BK, Schirmer B. Teaching writing to deaf students: does research offer evidence for practice? Remedial Spec Educ. 2013;34:166–179.

- Dostal HM, Wolbers KA. Examining student writing proficiencies across genres: results of an intervention study. Deafness Educ Int. 2016;18:159–169.

- Wolbers K, Dostal HM, Graham S, et al. Strategic and interactive writing instruction: an efficacy study in grades 3-5. JEDP. 2018;8:99.

- Braaksma M, Rijlaarsdam G, van den Bergh H. Observational learning and the effects of model-observer similarity. J Educ Psychol. 2002;94:405–415.

- Braaksma M, Rijlaarsdam G, van den Bergh H, et al. Observational learning and its effects on the orchestration of writing processes. Cogn Instr. 2004; 22:1–36.

- Rijlaarsdam G, Braaksma M, Couzijn M, et al. Observation of peers in learning to write: practice and research. J Writ Res. 2008;1:53–83.

- Grenner E, Åkerlund V, Asker-Árnason L, et al. Improving narrative writing skills through observational learning: a study of Swedish 5th-grade students. Educ Rev. 2020;72:691–710.

- van de Weijer J, Åkerlund V, Johansson V, et al. Writing intervention in university students with normal hearing and in those with hearing impairment: can observational learning improve argumentative text writing? Logoped Phoniatr Vocol. 2019;44:115–119.

- Clark JG. Uses and abuses of hearing loss classification. ASHA. 1981;23:493–500.

- Johansson V. Developmental aspects of text production in writing and speech. Lund (Sweden): Lund University; 2009.

- Frid J, Johansson V, Johansson R, et al. Developing a keystroke logging program into a writing experiment environment. Writing across borders; 2014.

- Tillema M, van den Bergh H, Rijlaarsdam G, et al. Quantifying the quality difference between L1 and L2 essays: a rating procedure with bilingual raters and L1 and L2 benchmark essays. Lang Test. 2013;30:71–97.

- Raedts M, Steendam E, Grez L, et al. The effect of different types of video modelling on undergraduate students’ motivation and learning in an academic writing course. J Writ Res. 2017;8:399–435.

- Wolff U. Lilla DUVAN. Stockholm (Sweden): Hogrefe Psykologiförlaget AB; 2010.

- Bishop DVM. Test for reception of grammar, version 2. Swedish version. Stockholm (Sweden): Pearson Education; 2009.

- Nielsen JC, Jensen SE, Magnusson E, et al. Ordläsningsprov OS64 och OS120, meningsläsningsprov SL60 och SL40 [Word reading test OS64 and OS120, sentence reading test SL60 and SL40]. Malmö: Pedagogisk design, 1997.

- Team RC. A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna (Austria): R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014.

- Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, et al. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4 [sparse matrix methods; linear mixed models; penalized least squares; Cholesky decomposition]. J Stat Softw. 2015;67:48.

- Sundström S, Löfkvist U, Lyxell B, et al. Phonological and grammatical production in children with developmental language disorder and children with hearing impairment. Child Lang Teach Ther. 2018;34:289–302.

- Hansson K, Ibertsson T, Asker-Árnason L, et al. Phonological processing, grammar and sentence comprehension in older and younger generations of Swedish children with cochlear implants. Autism Dev Lang Impair. 2017;2:239694151769280.

- Cooper H, Nye B, Charlton K, et al. The effects of summer vacation on achievement test scores: a narrative and meta-analytic review. Rev Educ Res. 1996;66:227–268.

- Rosqvist I, Sandgren O, Andersson K, et al. Children’s development of semantic verbal fluency during summer vacation versus during formal schooling. Logoped Phoniatr Vocol. 2020;45:134–142.

- Suggate S, Schaughency E, McAnally H, et al. From infancy to adolescence: the longitudinal links between vocabulary, early literacy skills, oral narrative, and reading comprehension. Cognitive Development. 2018;47:82–95.

- Bishop D, Edmundson A. Specific language impairment as a maturational lag: evidence from longitudinal data on language and motor development. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1987;29:442–459.

- Bruce B, Kornfält R, Radeborg K, et al. Identifying children at risk for language impairment: screening of communication at 18 months. Acta Paediatr. 2003;92:1090–1095.

- Yoshinaga-Itano C, Sedey AL, Coulter DK, et al. Language of early- and later-identified children with hearing loss. Pediatrics. 1998;102:1161–1171.

- SPSM. Måluppfyllelse för döva och hörselskadade i skolan [Academic achievement for students with deafness or hearing loss]. Specialpedagogiska skolmyndigheten (Swedish National agency for special needs education and schools). 2008.