Abstract

During the last three decades, the most prevalent surgical mitral valve disease in Scandinavia has changed from the sequelae of rheumatic fever to the mitral valve pathologies related to ischemic heart disease. Also, the total number of patients in need of a mitral valve procedure is increasing. For several of the patients with ischemic mitral valve disease, the natural prognosis of their disease is dismal. However, there are several uncertainties as to whether or not a surgical procedure can improve the life expectancies of these patients. Also, the procedures of choice for patients with ischemia related “functional mitral valve disease” is a long standing controversy. In this issue of “Scandinavian Cardiovascular Journal” we present the rationale and protocol for the “MoMIC” trial, a randomized multicenter study aiming to clarify whether revascularization alone or a combined revascularization and mitral valve annuloplasty is the treatment of choice for patients with ischemia related moderate mitral regurgitation.

From rheumatic disease to ischemic mitral regurgitation

The very first paper published in this journal back in 1967, then the Scandinavian Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, was entitled “Mitral valve surgery” by Russel Claude Brock Citation1. He was by then appointed “Lord” for his contribution to medicine and cardiac surgery and his whole paper was devoted to his view on the treatment of rheumatic mitral valve disease. He advocated the disappearing art of closed commisurotomy, but he would not “weary the reader with statistical review of all his cases”, but instead gave a tale of an experience in harmony with the zeitgeist.

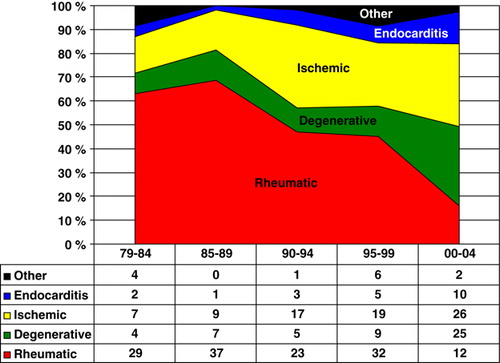

Since Lord Brocks paper, the epidemic proportions of rheumatic fever has faded in Scandinavia. shows the surgical experience with mitral valve surgery in Tromsø since the start of cardiac surgery in 1978. As expected, the number of procedures for rheumatic mitral valve disease is diminishing. There is, however, a small but still steady increase in the total number of surgical mitral procedures. By now, surgery for degenerative mitral valve disease and ischemic mitral regurgitation are the dominating groups. Of notice, the elderly patients still presenting with the late sequelae from rheumatic disease often belong to the group of patients with extensive calcification of the mitral ring, an ominous sign and at times a considerable technical challenge at surgery Citation2, Citation3.

Figure 1. Distribution of different diagnostic categories of mitral valve disease treated surgically. The number of procedures in each category is given for five year periods.

Surgery for mitral valve disease is not prevalent in Scandinavia. Calculating the number of procedure done in 2006 using data from the national registries reveals that the number of procedures per 100 000 inhabitants in that year was 6 in Norway and Iceland and 7 in both Denmark and Sweden (figures from Finland could not be obtained). This is less than one tenth of the prevalence of coronary surgery. The number of procedures done for degenerative mitral valve disease is probably around 1-2 per 100 000 inhabitants/year. In our experience, most of these patients have simple prolapses of the posterior leaflet and extensive Barlow's degenerative disease with big floppy valves is close to non-existent in our patient population. Thus, the timely focus on repair techniques benefits mostly a small but still important group of patients. As early treatment of asymptomatic mitral regurgitation has moved into the guidelines Citation4, the need for a safe and predictable repair in these low risk patients is very pertinent.

The challenges of ischemic mitral regurgitation

As seen from the , the ischemic etiology is dominating in our population. This reflects the high prevalence of coronary heart disease, particularly in northern Norway, where the invasive treatment of coronary heart disease is among the highest in Europe Citation5. Thus, our patient population demands an involvement and focus on the treatment effects and outcome in patients with coronary heart disease and mitral regurgitation.

Anatomically, blood to the anterior papillary muscle is mainly supplied by terminal diagonal branches from the left anterior descending while the posterior papillary muscle is supplied by the posterior descending from the right coronary. Logically, patients with mitral regurgitation as a consequence of coronary heart disease will be a very heterogeneous group with variation in coronary pathology, variations in acuteness and extent of infarction, variation of remodeling and variation in the influence of concomitant pathology, like hypertension. The common denominator for these patients is a myocardial and ventricular dysfunction, not primarily valve destruction. Thus, the concept of “functional mitral regurgitation” contains a host of different myocardial pathologies influencing the mitral valve function in various ways.

There are a series of uncertainties and treatment insufficiencies plaguing the handling of these patients. Firstly, the mechanism for MR is in most cases probably due to an outward movement of the inferior wall of the left ventricle and a concomitant downward and outward pull on the cordae attached to both the anterior and posterior mitral leaflets. The movement of the post infarct ventricular wall is often asymmetrical, and these factors in common lead to a failed coaptation of the two mitral leaflets and a following regurgitation during systole. Of importance, annular dilatation is often not part of the dysfunction, and a prolaps due to papillary muscle malfunction (or elongation) is almost non-existent in these patients Citation6.

Secondly, the restrictive mechanism has lead to a surgical approach using a small annuloplasty ring to “compress” the mitral annulus and a following attempt to increase the coaptation area between the two leaflets. However, such an approach leads to a high number of secondary failures Citation7, Citation8 and also in a number of cases to a “functional mitral stenosis” Citation9. An attempt has been done to both cut restrictive cordae Citation10, to increase the area of the posterior leaflet Citation11 or to reapproximate the papillary muscles Citation12. However, none of these procedures have induced a permanent change of techniques for surgical treatment.

Thirdly, large series of patients with ischemic mitral regurgitation demonstrate two important findings. The medium term prognosis for many of these patients is very dismal and for some of these patients an annuloplasty seems to have no benefit compared to a valve implantation Citation13, Citation14. On the contrary, for some of these patients a solution with a primary “valve sparing prosthesis” might be the best we have to offer Citation15. Certainly, it is of paramount importance that the various physicians handling these patients know that the demand for a repair has a different meaning for an asymptomatic patient with a simple P2 prolapse compared to a patient with ischemic mitral regurgitation from a badly failing left ventricle!

Finally, most of our common experience with “functional ischemic mitral regurgitation” relates to patients with remodeled ventricles from remote myocardial infarctions. These reasonably stable patients can be offered surgery without prohibitive operative mortality; in our experience all 21 patients with an ejection fraction less than 30% survived the 30 days after surgery. Importantly, this cannot be taken as an absolute need for surgery as no studies with necessary stringent design can demonstrate a long term benefit of surgery compared to medical treatment Citation16. As opposed to these “chronic” patients”, in patients with an ongoing myocardial infarction complicated by acute heart failure and mitral regurgitation, the operative mortality is substantial (40% in the Shock trial registry, Citation17). For eligible patients in this category, the best choice at present is probably an assist device as a primary treatment option.

The MoMIC trial

It is on this backdrop of “unknowns and insufficiencies” we welcome the MoMIC trial (“moderat mitral regurgitation in patients undergoing CABG”) Citation18, Citation19. This trial has been initiated from Skejby and its principal investigator Per Wierup. The study will hopefully include 550 patients with coronary stenoses demanding surgery and a concomitant moderate mitral regurgitation defined as an echocardiographically “effective regurgitant orifice area” of 15-30 mm2. These patients will be randomized to CABG alone (group 1) or to CABG with a concomitant mitral procedure, preferably annuloplasty (group 2). End points will be hospitalization for heart failure or death within five years.

The MoMIC initiative will involve a number of centers in Scandinavia, in the US and in Canada. Such a randomized surgical trial is probably the best way forward to gain some of the lacking knowledge on how to treat patients with mitral regurgitation and coronary heart disease. Several decades of observational studies and experimental animal models have not solved the obvious question of whether or not we should “treat a myocardial disease with a valve procedure”. If conducted according to plan, the MoMIC trial should provide us with some of the answers we need to advise our patients based on sound knowledge.

We encourage participating centers to support the trial and put in an effort to optimize its qualities. As for all such trials there are insufficiencies and matters of controversy, but the planning has been done and inclusions have started.

To us there is only one statement from the MoMIC-trial that demands a comment at this point: “The benefit of adding mitral valve surgery to coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) is well documented in patients with a combination of coronary artery disease and severe mitral regurgitation.” Citation19. This statement is incorrect as it cannot be substantiated by the given references. The treatment choices for severe ischemic mitral regurgitation also lack documentation, and they are not obvious, particularly for patients with failing ventricles. Perhaps we will see a Scandinavian “Severe mitral regurgitation in dysfunctional ischemic ventricles or SeVIC trial” some time in the not too distant future?

References

- Lord Bock. Mitral valve surgery. Scand J Thor Cardiovasc Surg. 1967;1:1–6.

- Cammack PL, Edie RN, Edmunds LH. Bar calcification of the mitral annulus – risk factor in mitral valve operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1987; 94: 399–404

- Feidel CM, Tufail Z, David TE, Ivanov J, Armstrong S. Mitral valve surgery in patients with extensive calcification of the mitral annulus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003; 126: 777–81

- AHA/ACC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. Circulation. 2006;114:84–231.

- www.legeforeningen.no.

- Otsuji Y, Levine RA, Takeuchi M, Sakata R, Tei C. Mechanism of ischemic mitral regurgitation. J Cardiol. 2008; 51: 141–56

- Hung J, Papakostas L, Tahta SA. Mechanism of recurrent ischemic mitral regurgitation after annuloplasty; continued LV remodeling as a moving target. Circulation 2004; 110: I185–I190

- Zhu F, Otsuji Y, Yotsumoto G. Mechanism of persistent ischemic mitral regurgitation after mitral annuloplasty; importance of augmented posterior mitral leaflet tethering. Circulation. 2005; 112: I396–I401

- Magne J, Senechal M, Mathieu P, Dumesnil JG. Restrictive annuloplasty for ischemic mitral regurgitation may induce functional mitral stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008; 51: 1692–701

- Borger MA, Murphy PM, Adam A, Fagel S, Maganti M, Armstrong S, et al. Initial results of the chordal-cutting operation for ischemic mitral regurgitation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007; 113: 1483–92

- Dobre M, Koul B, Rojer A. Anatomical and physiological correction of the restricted posterior mitral leaflet motion in chronic ischemic mitral regurgitation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000; 120: 409–11

- Fumimoto K, Fukui T, Shimokawa T, Takanashi S. Papillary muscle realignment and mitral annuloplasty in patients with sever ischemic mitral regurgitation and dilated ventricles. Interact Cardiovasc Thoracic Surg. 2008; 7: 368–71

- Grossi EA, Goldberg JD, LePietra A, Ye X, Zakow P, Sussman M, et al. Ischemic mitral valve reconstruction and replacement; comparison of long-term survival and complications. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001; 122: 1107–24

- Gillinov AM, Wierup PN, Blackstone EH, Bishey ES, Cosgrove DM, White J, et al. Is repair preferable to replacement for ischemic mitral regurgitation?. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001; 122: 1125–41

- Miller DC. Ischemic mitral regurgitation redux – to repair or to replace?. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001; 122: 1059–62

- Wu AH, Aaronsen KB, Bolling SF, Pagani FD, Welch K, Koelling TM, et al. Impact of mitral valve annuloplasty on mortality risk in patients with mitral regurgitation and left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 45: 381–7

- Thompson CR, Buller CE, Sleeper JA, Antonelli JA, Webb J, Jaber WA, et al. Cardiogenic shock due to acute severe mitral regurgitation complicating acute myocardial infarction. A report from the SHOCK trial registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000; 36: 1104–9

- Wierup P, Lyager Nielsen S, Egeblad H, Scherstén H, Kimblad PO, Bech-Hansen O, et al. The prevalence of moderate mitral regurgitation in patients undergoing CABG. Scand Cardiovasc J. ( in press).

- Wierup P, Egeblad H, Lyager Nielsen S, Scherstén H, Kimblad PO, Bech-Hansen O, et al. Moderate mitral regurgitation in patients undergoing CABG – the MoMIC trial. Scand Cardiovasc J. ( in press).