Abstract

Background. The aim of this study was to evaluate gender differences in the long-term clinical outcomes and safety of patients treated with first- and second generation DES. Methods. The Katowice–Zabrze Registry included 1916 consecutive patients treated with either first or second generation DES. We evaluated major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) [composite of death, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke and target vessel revascularization (TVR)] at 12-month follow-up. Safety end point was bleeding complications and stent thrombosis. Results. Registry included [unstable angina (UA) 1500(78%), non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) 285 (15%), ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction/left bundle branch block (STEMI/LBBB) 131 (7%)]. There were 35.5% females and 64.5% males. Women were older and had higher prevalence of comorbidities. Males more often had multivessel disease and higher Syntax score when comparable to females. We did not observed difference in acute and subacute stent thrombosis in our data, however, females had more in-hospital bleeding complications. Univariable Cox regression analysis revealed that women had similar outcomes when compared to men in terms of a risk of death, MI, TVR, stroke and MACCE at 1-year follow-up. There were no differences between males and females in MACCE when first- and second generation DES were analyzed separately. Conclusion. Despite higher risk profile, women treated with DES have similar outcomes as males in 1-year follow-up. However there is, an increased risk of in-hospital bleedings in women.

Introduction

Large registries provide data which can be utilized to highlighted gender-related differences in presentation, access to interventional treatment and long term outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD). In a study conducted in Denmark by Hvelplund et al., women who presented with acute myocardial infarction (MI) were less often hospitalized and less likely to undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).[Citation1,Citation2] As well, women more often had microvascular disease as compared to men.[Citation3] Some studies showed that females have increased risk of major cardiovascular adverse events and bleeding complications,[Citation4,Citation5] while others, suggest that after adjustments for comorbidities, females can have better long-term survival post PCI than man.[Citation6,Citation7] Yu et al. noted that women presented with onset of symptoms later than men, they were treated with medical management alone and they had a higher 3-year rate of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) and bleeding. However, after adjusting for baseline differences, female sex was an independent predictor of major bleeding complications after PCI.[Citation8] Even in light of comorbidities, microvascular diseases and/or increased bleeding complications, a clear rationlization for the observed treatment differences between genders was not explained. Stent technology has progressed from first generation DES (I-DES) to second generation DES (II-DES). Both generational DES types are currently in use, it is possible that DES type could influence outcome observed between genders, treated from this therapy. There is limited data, which assess the impact of DES types (I-DES vs. II-DES) on PCI outcomes, in gender differences. We, therefore, examined the incidence of death and major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) in males and females and compare DES-I vs. DES-II in both groups on 1-year follow-up. The primary goal is to assess the implementation of the guidelines and evidence-based medicine into everyday clinical practice.

Methods and study population

The Katowice–Zabrze retrospective registry included 1916 consecutive patients treated with either first (paclitaxel, sirolimus-eluting; 33.6%) or second generation (everolimus, zotarolimus, biolimus A9, 66.4%) DES. Briefly, baseline characteristics, cardiac history, risk factors, medications, angiographic and procedural data were obtained and recorded. Angiographic data were collected on all patients undergoing PCI and recorded in the cardiovascular information registry. Syntax score was calculated for all patients without prior coronary artery bypass graft (CABG).

The primary efficacy end point was a composite of MACCE, including as all-cause death, non-fatal MI, target vessel revascularization (TVR) and stroke. The secondary end points were individual components of the primary end point (all-cause death, MI, TVR and stroke) and in-hospital bleeding. The safety of DES was defined as definite stent thrombosis (acute, subacute and late). TVR, definite stent thrombosis, acute, subacute and late stent thrombosis were defined according to the definitions of end points for clinical trials.[Citation9] Gastrointestinal bleeding was considered an end point if it fulfilled criteria for type 3 or type 5 bleeding according to proposed definitions.[Citation10] Data regarding long-term outcomes (MACCE and gastrointestinal bleeding) were obtained from the database of the National Health Fund Service (Ministry of Health).

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using MedCalc Software v.12 (Ostend, Belgium). Quantitative variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation and median with interquartile range (Q1–Q3). Qualitative data are expressed as crude values and/or percents. Between-group differences were assessed using Mann–Whitney U test for quantitative variables and Chi-square test for qualitative variables. Data distribution was verified with Smirnov–Kolmogorov test. Kaplan–Meier curves were used to present the unadjusted time-to-event data for investigated end points. Additionally, multivariable modeling was performed using Cox proportional hazards method to assess the adjusted association between all end points and DES type. All tests were 2-tailed. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Demographics, comorbidities and chronic medications

During 24 months between January 2009 and December 2010, 1916 patients were admitted with a final diagnosis unstable angina (UA) 1500 (78.2%), non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) 285 (14.8%) and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction/left bundle branch block (STEMI/LBBB) 131(6.8%). There were 680 (35.5%) females and 1236 (64.5%) males. Females were older and had higher prevalence of comorbidities: hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease and obesity but they were less often smokers. They also had less often a history of MI and CABG in comparison to males. According to the clinical presentation, females had higher blood pressure at admission. There were no differences across the spectrum of GRACE risk score (). According to the medical treatments, females received less often angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors but they were more often administered angiotensin receptor blockers and calcium channel blockers. There were no differences in other peri- and post-procedural medical treatment in both groups ().

Table 1. Patients’ characteristics, risk factors and clinical presentation according to the gender.

Table 2. Drug therapy according to the gender.

Left ventricular function

Left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) values were available in 98.7% of all patients. In general population LVEF was normal in 70% patients, moderately reduced (31–50%) in 24% and severely (≤30%) reduced in 6% of patients. Males had lower LVEF values as compared to females (53 IQR45–59 vs. 55 IQR 50–60, p < 0.001) ().

Interventional treatment and reperfusion strategy

Males had more often multivessel disease – three or more disease vessel (30.1% vs. 21.9%, p < 0.001) and higher Syntax score comparable to female (16 IQR 9–25 vs. 13 IQR 7–20, p < 0.001). Males were more frequently treated with II-DES and females were more frequently treated with I-DES ().

Table 3. Angiographic and procedural data according to the gender.

In-hospital and 30 days outcomes

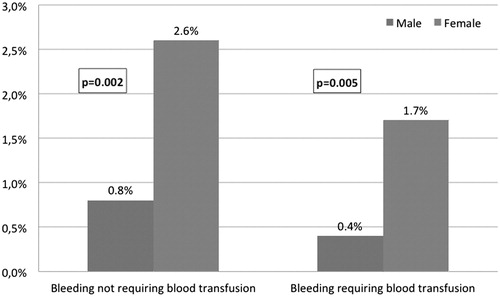

There were a significantly higher rate of in-hospital bleedings requiring blood transfusion (1.7% vs. 0.4%, p = 0.005) and bleedings not requiring blood transfusion (2.6% vs. 0.8%, p = 0.002) in females as compared to males (). Moreover, women had longer hospitalization time compared to males (p < 0.001). There were no differences in the use of intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP), respiratory insufficiency and cardiac arrest during hospitalization in both groups. Even so, we did not observe differences in rates of acute and subacute stent thrombosis in males or females ().

Table 4. In-hospital and long-term follow-up according to the gender.

12-Month outcomes

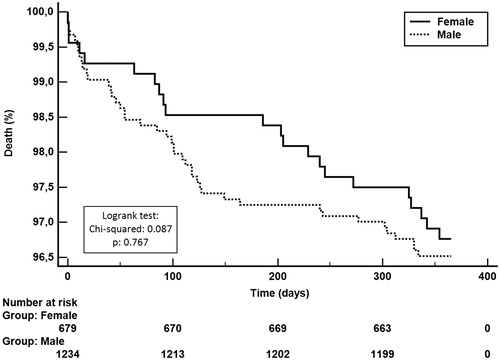

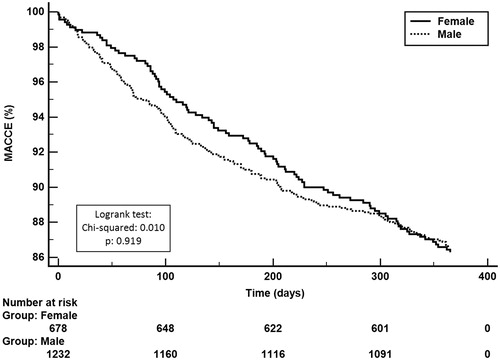

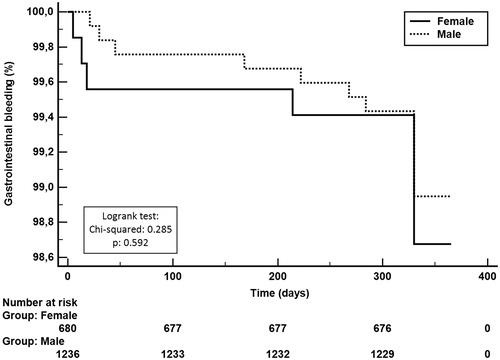

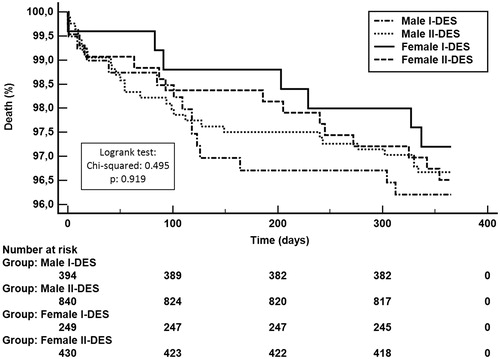

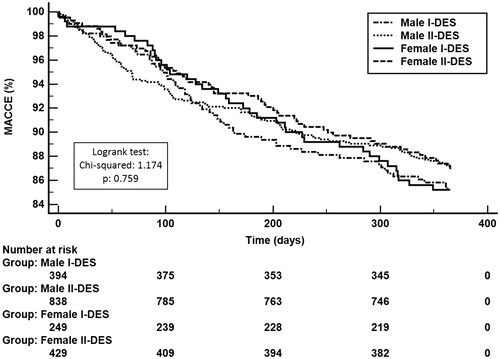

12-month follow-up revealed that women had similar outcomes as men in terms of death [HR = 1.08 (95%CI 0.64–1.82), p = 0.880], MI [HR = 0.72 (95%CI 0.47–1.09), p = 0.149], TVR [HR = 1.05 (95%CI 0.75–1.46), p = 0.849], stroke [HR = 1.38 (95%CI, 0.43–4.41), p = 0.792] and MACCE [HR = 0.97 (95%CI, 0.75–1.28), p = 0.977]. Twelve month cumulative rate of late stent thrombosis did not differ significantly between males and females (p = 0.797). Survival probability at 12 months was presented using Kaplan–Meier curves stratified on males vs. females in . The rates of gastrointestinal bleeding were low and did not differ between groups (p = 0.592) ().

Multivariate Cox regression analysis revealed that gender was not an independent risk factor of death among CAD patients and DES users but chronic kidney disease, peripheral artery disease, ejection fraction lower than 50% and age over 65 years were (). The comparisons of DES generational use in males and females showed that the cumulative rate of death did not differ significantly among I-DES vs. II-DES in males [HR = 1.1 (95%CI 0.61–2.14), p = 0.658] and females [HR = 0.93 (95%CI 0.37–2.32), p = 0.885] (). Moreover there were no differences in cumulative rate of MACCE between I-DES vs. II-DES in males [HR = 1.1 (95%CI 0.80–1.51), p = 0.538] and females [HR = 0.91 (95%CI 0.60–1.39), p = 0.669] ().

Table 5. Multivariate analysis regression.

Discussion

The present all-comer registry demonstrated some significant gender disparities with regard to clinical and angiographic presentation of patients with ACS. Women had a higher risk of adverse events, however, 1-year MACCE were equal in men and women. Importantly, there was a gender disparity in use of newer, more efficient generation of DES.

Analysis of available angiographic data demonstrated that there were some gender differences in terms of the complexity coronary atherosclerotic lesions. Similar to Stefanini et al., [Citation11] we noted that males despite younger age have more complex coronary lesions measured by Syntax score. In addition they reported no differences in TVR, and stent thrombosis between males and females in 2-years follow-up after DES implantation. The same angiographic outcomes have been demonstrated after PCI with sirolimus-eluting stent [Citation12] or paclitaxel-eluting stent [Citation5] implantation, analyzed separately. Shammas et al. [Citation13] evaluate differences for males and females treated with everolimus-eluting stents and paclitaxel-eluting stents. At 2-year follow-up, there was no difference in target lesion revascularization, cardiac death and stent thrombosis. Results from Scandinavian Organization for Randomized Trials with Clinical Outcome (SORT OUT IV and V) also did not observe gender differences in patients treated with first- or second generation DES.[Citation14] There is only one study, which compared DES generation in females. Giustino et al. [Citation15] investigated the safety and efficacy of II-DES vs. I-DES in women undergoing complex PCI. The use of II-DES was associated with lower 3-year risk of MACE, target lesion revascularization and stent thrombosis. However, stent thrombosis was more apparent in the very-late period (>1 year).

The outcomes after coronary revascularization are improving. Nowadays mainly II-DES are used during PCI, they are characterized by thinner struts, more biocompatible polymer coating (often biodegradable). They have more flexibility and deliverability and have smaller thickness struts compared to I-DES.

While, females have more frequently narrower, more tortuous vessels, more comorbidity and females sex has been reported to be predictive of in-stent restenosis [Citation16] the II-DES are better choice. II-DES are associated with lower risk of restenosis, stent thrombosis and a lower risk of death compared with I-DES [Citation17,Citation18] in general population.

In this study despite the lack of differences in antiplatelet therapy there still was an increased risk of in-hospital bleeding, requiring blood transfusion in women. Bleeding is the most common non-ischemic complication observed post PCI,[Citation19] and red blood cell transfusion is associated with an increased risk of CV events.[Citation20] Moreover according to the ACUITY trial [Citation21] major bleeding is associated with higher ischemia, and stent thrombosis compared to patients without major bleeding and is an independent predictor of 30-day mortality. Therefore, those patients need an individualized antiplatelet therapy approach to decrease thrombotic events without increasing bleeding.[Citation22,Citation23] Choosing the best vascular approach during PCI can significantly reduce the risk of bleeding. Radial access is associated with significant reduction in major bleeding and need for blood PCI transfusions.[Citation8] Data from other studies demonstrated a strong association between gender differences and increased risk of bleeding complications in patients with CAD, who were managed invasively. Birkemeyer et al. [Citation24] indicated that women with STEMI more often had major bleeding than men in short- and long-term follow-up. Similar results were observed by Hess et al. [Citation25] in MI patients. He examined the incidence of the bleeding event within 1-year post PCI according to GUSTO and BARC definitions. In his study women were associated with higher risks of post-PCI GUSTO bleeding (9.1% vs. 5.7%) and post-discharge BARC bleeding (39.6% vs. 27.9%). We examined the incidence of the gastrointestinal bleeding event within 1-year post PCI and did not observe any differences between both groups. But in contrast results from the HORIZONS- AMI Trial illustrated that women have almost a two-fold risk of bleeding compared with men either in short-term as well as long-term follow-up.[Citation8]

Conclusion

Women presenting with CAD tend to be older and had more comorbidities. In women, the risk of bleeding post PCI is significantly higher when compared with men. Despite the higher risk profile, women treated with either type of DES are not at increased risk of death or MACCE at 1-year follow-up or stent thrombosis, as compared to men.

Study limitations

Patients were not randomized as to a choice of stent implantation (DES first or second generation), so there was no balance between I-DES and II-DES. There was no information on drugs used before admission to hospital, especially those with a known impact on bleeding (e.g., VKA, NOAC). There was no information about the duration of medication (example patients taking clopidogrel) after PCI.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2–e220.

- Hvelplund A, Galatius S, Madsen M, et al. Women with acute coronary syndrome are less invasively examined and subsequently less treated than men. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:684–690.

- Pepine CJ, Kerensky RA, Lambert CR, et al. Some thoughts on the vasculopathy of women with ischemic heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:S30–S35.

- Cowley MJ, Mullin SM, Kelsey SF, et al. Sex differences in early and long-term results of coronary angioplasty in the NHLBI PTCA Registry. Circulation. 1985;71:90–97.

- Lansky AJ, Pietras C, Costa RA, et al. Gender differences in outcomes after primary angioplasty versus primary stenting with and without abciximab for acute myocardial infarction: results of the controlled abciximab and device investigation to lower late angioplasty complications (CADILLAC) trial. Circulation. 2005;111:1611–1618.

- Berger JS, Sanborn TA, Sherman W, et al. Influence of sex on in-hospital outcomes and long-term survival after contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J. 2006;151:1026–1031.

- Anderson ML, Peterson ED, Brennan JM, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes of coronary stenting in women versus men: results from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry Centers for Medicare & Medicaid services cohort. Circulation. 2012;126:2190–2199.

- Yu J, Mehran R, Grinfeld L, et al. Sex-based differences in bleeding and long term adverse events after percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction: three year results from the HORIZONS-AMI trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;85:359–368.

- Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115:2344–2351.

- Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;123:2736–2747.

- Stefanini GG, Kalesan B, Pilgrim T, et al. Impact of sex on clinical and angiographic outcomes among patients undergoing revascularization with drug-eluting stents. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:301–310.

- Solinas E, Nikolsky E, Lansky AJ, et al. Gender-specific outcomes after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2111–2116.

- Shammas NW, Shammas GA, Jerin M, et al. Sex differences in long-term outcomes of coronary patients treated with drug-eluting stents at a tertiary medical center. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2014;10:563–567.

- Jensen LO, Thayssen P, Christiansen EH, et al. 2-year patient-related versus stent-related outcomes: the SORT OUT IV (Scandinavian Organization for Randomized Trials With Clinical Outcome IV) Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1140–1147.

- Giustino G, Baber U, Aquino M, et al. Safety and efficacy of new-generation drug-eluting stents in women undergoing complex percutaneous coronary artery revascularization: from the WIN-DES collaborative patient-level pooled analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:674–684.

- Dangas GD, Claessen BE, Caixeta A, et al. In-stent restenosis in the drug-eluting stent era. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1897–1907.

- Sarno G, Lagerqvist B, Frobert O, et al. Lower risk of stent thrombosis and restenosis with unrestricted use of 'new-generation' drug-eluting stents: a report from the nationwide Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR). Eur Heart J. 2012;33:606–613.

- Kawecki D, Morawiec B, Dola J, et al. First- versus second-generation drug-eluting stents in acute coronary syndromes (Katowice-Zabrze Registry). Arq Bras Cardiol. 2016;106:373–381.

- Hamm CW, Bassand JP, Agewall S, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: the task force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2999–3054.

- Bassand JP, Afzal R, Eikelboom J, et al. Relationship between baseline haemoglobin and major bleeding complications in acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:50–58.

- Manoukian SV, Feit F, Mehran R, et al. Impact of major bleeding on 30-day mortality and clinical outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes: an analysis from the ACUITY trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49: 1362–1368.

- Winter MP, Kozinski M, Kubica J, et al. Personalized antiplatelet therapy with P2Y12 receptor inhibitors: benefits and pitfalls. Postepy Kardiol Interwencyjnej. 2015;11:259–280.

- Sheyin O, Perez X, Pierre-Louis B, et al. The optimal duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients receiving percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents. Cardiol J. 2016;23:307–316.

- Birkemeyer R, Schneider H, Rillig A, et al. Do gender differences in primary PCI mortality represent a different adherence to guideline recommended therapy? a multicenter observation. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014;14:71.

- Hess CN, McCoy LA, Duggirala HJ, et al. Sex-based differences in outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction: a report from TRANSLATE-ACS. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000523.