Abstract

An international collaboration on various aspects of acute aortic syndromes, IRAD or The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissections, is celebrating its 20th anniversary this year (2016). In this paper, we present important lessons learned during these first 20 years.

Paper

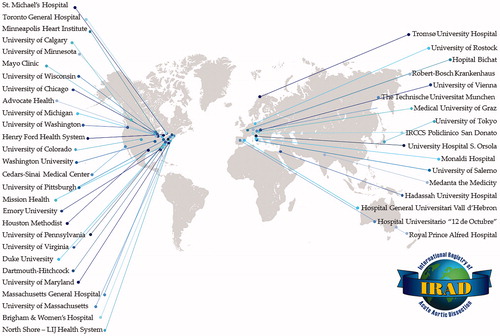

The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissections (IRAD) was established in 1996 as a collaborative effort between 12 aortic centers in six countries. The Registry was, and still is, investigator driven with relatively few permanent supportive resources except for an established dedicated staff and facilities at Michigan Cardiovascular Outcomes Research Reporting Program (MCORRP). IRAD is led by Professor Kim Eagle (Michigan), supported by Christoph Nienaber (Royal Brompton & Harefield, London) and Eric Isselbacher (Harvard University), the “founding fathers” of the database. Today IRAD receives data from 43 centers worldwide, and the database contains core data from more than 6500 patients ().

IRAD contains patients with both acute type A and B dissections, and patients are included if they have a symptom onset of less than two weeks, i.e. present to the centers in the acute phase of the dissection. Data for each patient are collected through a case report form (CRF) with 290 variables and the patients are followed for five years after the initial presentation of the disease. The CRF has sections for demographic and clinical variables, imaging, treatment and outcomes. From 2010, a dedicated section of the IRAD, the Invasive treatment group, has established a more extensive data form with particular attention to details of invasive treatment outcomes, both TEVAR, i.e. Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair and surgical treatment.

The IRAD database – clinical epidemiology describing trends in the “real world”

The first publication from IRAD presented “new insights into an old disease” and included 464 patients from the initial 12 centers. The paper described a 26% acute surgical mortality in type A patients and an initial hospital mortality in type B patients of 10%.[Citation1] This publication truly qualifies as a “landmark paper” as these observations reflected the status for aortic dissection treatment at the turn of the millennium and clearly outlined the challenges still facing aortic centers. This JAMA publication has by now been cited 1131 times (June 2016).

A follow-up paper from 2015 included 4438 patients (included in the database up until February 2013).[Citation2] This survey documented that 90% of patients with type A dissection receive surgical treatment in the present era and that 31% of patients with type B dissection admitted to IRAD centers had TEVAR during their initial hospital stay in the most recent period. Hospital mortality for patients treated surgically for type A dissection has come down somewhat (to 18%), but no improvement has been observed in the in-hospital mortality for type B patients. This is a particularly important observation as there is a small, albeit non-significant, trend towards an increased initial hospital mortality in type B patient occurring concomitantly with an increased utilization of stentgrafts in the acute phase. Registries have their greatest merit in telling us the “hard facts” about the results of our current and previous treatment efforts.

IRAD has been built as a “pragmatic” investigators database. This means that each center is responsible for providing their CRF data and do the follow up assessment for five years. By including a high number of centers, a large number of patients will have their initial hospital data registered, but follow up will for many site-specific reasons vary between centers. Also, the IRAD does not provide a core lab for detailed assessment of the data provided, and registration of data will stop at five years, or when the patient dies in the period before the end of five years. The strength is in the substantial number of patients included, shortcomings are related to treatment heterogeneity and variation in follow-up frequencies. The data do reflect, however, a mirror image of practical care and treatment throughout the world.

In spite of these limitations, IRAD data support the observations [Citation3,Citation4] that surgically treated type A dissection patients most often can expect a stable period during the first five years after surgery.[Citation5] One- and three-year survivals for successfully operated patients with type A were found to be 96 and 91%, respectively. Also, exceedingly few type A patients need reoperation for root problems [Citation5] or dilated aortas [Citation3,Citation4] in this first five-year period.

However, aortic dissection is “a disease for life”, except perhaps for DeBakey type II dissections where all of the pathological tissues have been removed during surgery.[Citation6] In particular, patients with a type B dissection need a close and vigorous follow-up based on aortic imaging. Treatment algorithms for type B dissections are less clear than for type A dissections,[Citation7] and optimal medical treatment, stentgrafting and surgery are used on a patient-specific basis. Three-year survival for patient with type B dissection treated medically at IRAD centers has been 78%, treated with stentgrafts 76% and surgery 83%.[Citation8] These outcomes are certainly not optimal and argue for refinement in handling, hopefully through new technology in person-specific imaging,[Citation9] sophisticated calculation of wall stress [Citation10] and in vivo biochemical activity in the remodeling aortic wall.[Citation11]

Several of the follow-up data in IRAD are testimony to sound medical judgement. Comparing extensive root surgery to a conservative approach,[Citation5] and simple ascending aorta replacement to a full aortic arch replacement,[Citation12] revealed no differences in procedure-related or follow-up mortality. As these different treatment options are surgeon’s preference, the results indicate that the therapy traditions evolved over the years have merit.

Important observations of the nature of aortic dissection – the risk factors

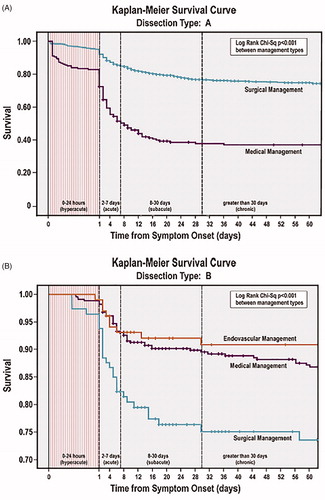

Given the large datasets collected by the IRAD, the database lends itself particularly to assessments of which factors that do influence the course of the disease and which factors that are important for the treatment outcome. From such analyses, it has become apparent that the 60-year-old separation into an unstable acute phase (less than two weeks) and a more stable chronic phase after two weeks should be readdressed.[Citation13] By assessing the survival attrition, it became apparent that the first month after the dissection is the most critical (). In addition, the survival curves show that for both type A and B, the choice of treatment alters the critical phases in different ways. For instance, for the few patients treated conservatively for a type A dissections, mortality will be expected around 50% the first week, and surgically treated type B patients have a critical postoperative course for the first month with an accumulated mortality around 30%. For type B patients treated with optimal medical regimens, the attrition is more continuous demanding a vigorous surveillance also after the initial hospital stay.

Figure 2. (A) Kaplan?Meier survival curve for type A dissection stratified by treatment type. (B) Kaplan?Meier survival curve for type B dissection stratified by treatment type. From The American Journal of Medicine 2013; 126, 730. e19–730.e24, with permission from the publisher (Elsevier Inc).

There is an overwhelming amount of data showing that the extent of aortic wall splitting determines the prognosis of the patients with aortic dissection. It is a sobering fact that the patients we see in hospitals are a selected part of patients affected by dissections. In a survey of the population of Oxford shire (92,000 inhabitants) published by the Oxford Vascular Study [Citation14] using community health data and extensive autopsies, the overall mortality at 30 day for type A dissections was 73% and for B dissections 13%. These observations are somewhat reflected in the IRAD data analyzing prognostic factors for mortality.

Patient related factors predicting mortality is outlined in . Circulatory compromise reflected in hypotension, shock and tamponade increases mortality in both type A and type B patients. In addition, malperfusion and intestinal organ ischemia increase patient risk for both surgery, TEVAR and conservative treatment. For surgically treated type A patients, previous cardiac surgery adds to the complexity and is reflected by an increased mortality.

Table 1. Ominous factors for survival in type A and type B aortic dissections.

As of today, for patients with so-called uncomplicated type B dissections, we recommend optimal medical treatment and close surveillance.[Citation7] However, data from IRAD have shown that there is an intermediate risk group with continuous pain, poor control of blood pressure, expanding aortic dimensions and/or periaortic hematomas that appear to benefit from early invasive therapy, preferably TEVAR.[Citation15]

The fate of the false lumen

Intuitively, persistent flow in the false lumen of the aorta is undesirable and will be a marker for an unwanted remodeling of the aortic wall with potential aneurysmal development and late rupture.[Citation16] One of the most cited IRAD-observations also found that a false lumen with a partial thrombosis in this segment marks an ominous course for patients with a type B dissection.[Citation17] A potential pathophysiological explanation for this could be an increased pressure in the wall due to a “cul de sac” effect when there is no, or small, re-entries of blood.[Citation18] However, a partial thrombosis in the false lumen does not seem to be a negative prognostic sign for patients operated for a type A dissection.[Citation19] In these aortas, the primary entry tear in the intima has been removed, and therefore the lumen has probably been largely depressurized, much like the effect of a successfully placed stentgraft. There is still only scant data to address these issues,[Citation16] and the supportive data are largely driven by data from IRAD. An alternative mechanism for the unwanted effects of thrombus could potentially be related to biochemical effector mechanisms hampering a protective remodeling.

TEVAR in acute aortic dissections?

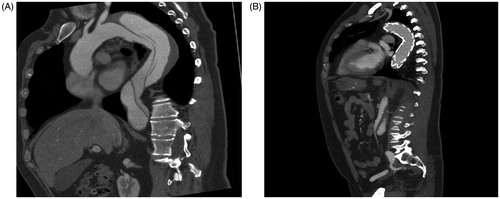

Currently, much debate has been focused on whether or not to apply a proximal stentgraft in all patients with a type B dissection with an applicable anatomy. Two small underpowered randomized studies, the INSTEAD study [Citation20] and the ADSORB study [Citation21] have addressed this issue in subacute and truly acute scenarios, respectively. These studies found no immediate benefit compared to optimal medical treatment, but TEVAR promotes anatomically beneficial aortic remodeling long-term (), and the INSTEAD study suggested a survival benefit for TEVAR patients at five years follow up.

Figure 3. The placement of a stentgraft covering the entry tear in type B dissection will promote remodeling of the aortic wall, particularly in the proximal part with predisposition for late dilatation. (A) Morphology of dissected aortic wall. (B) Remodeling of the aorta after placement of stentgraft.

The IRAD data have some indication to the effects of TEVAR in acute type B dissections. In a comparison of medical treatment (n = 390), open surgery (n = 59) and TEVAR (n = 66) in patients treated between 1996 and 2005, the in-hospital mortality was 33.6% for surgery and 10.6% in the TEVAR group.[Citation22] Admittedly, the patients were not of equal risk profile or matched, but this study has since supported the emerging recommendations for TEVAR as the first option in complicated type B aortic dissection.[Citation7] In a follow-up analysis [Citation23] of 1129 type B patients treated between 1996 and 2012, TEVAR patients (n = 276) had a five-year mortality of 15.5% compared to 29.0% mortality in 853 patients treated medically despite an equal hospital mortality in the two groups. Importantly, the TEVAR patients had a higher risk profile with organ ischemia, circulatory compromise and renal failure. These studies add to an increasing data collection promoting TEVAR for beneficial long-term remodeling of the aorta.

Lessons learned – IRAD from a Nordic perspective

Aortic dissections are relative rare occurrences, albeit serious, with a yearly incidence of 5–10/100,000 inhabitants. As such, to gather sufficient amount of data to forward knowledge and improve treatment results is difficult. The experiences from IRAD demonstrate that an international collaborative effort can, with relatively limited resources, provide large amounts of necessary data in a reasonably short time period. For diseases like endocarditis, genetic subgroups of vascular diseases, rare forms of aneurysms and treatments like extracorporeal circulatory support (ECMO), a similar construction of databases will probably have the same beneficial outcome. The establishment of an “International collaboration on Endocarditis (ICE)” and the “Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO)” is testimony to the fact that such international collaborations are gaining momentum. For IRAD, the “next level” will probably involve subgroups with particular focusses, like invasive treatment, imaging, genetics and optimal medical treatment.

In a global perspective, few people reside in the Nordic countries. Thus, it is of particular interest for us to expand our registries and participate in the “big data” collections from international initiatives like IRAD. We are already registering vast amounts of data in our respective national databases, and adding the international collaborative aspect should be relatively straight forward both from an aspect of technical solutions and resources spent. There is a definitive challenge in protecting the security of sensitive person-specific information stored in our health-related databases, and these aspects need to be the focus of particular scrutiny in the years to come.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Funding

This work was supported by the Health Authorities of North Norway and a Fellowship from The Norwegian Cardiovascular Foundation (Hjerte-karrådet) (ML).

References

- Hagan PG, Nienaber CA, Isselbacker EM, et al. The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD): new insights into an old disease. JAMA. 2000;283:897–903.

- Pape LA, Awais M, Wogriecki EM, et al. Presentation, diagnosis, and outcomes of acute aortic dissection: 17-year trends from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:350–358.

- Albrecht F, Eckstein F, Matt P. Is close radiographic and clinical control after repair of acute type A aortic dissection really necessary for long-term survival? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2010;11:620–625.

- Geirsson A, Bavaria JE, Swarr D, et al. Fate of the residual distal and proximal aorta after acute type A dissection repair using a contemporary surgical reconstruction algorithm. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:1955–1964.

- Eusanio MD, Trimarchi S, Peterson MD, et al. Root replacement surgery versus more conservative management during type A acute aortic dissection repair. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98:2078–2085.

- Safi HJ, Miller CC, Reardon MJ, et al. Operation for acute and chronic aortic dissection: recent outcome with regard to neurologic deficit and early death. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:402–411.

- Fattori R, Cao P, De Rongo P, et al. Interdisciplinary expert consensus document on management of type B aortic dissection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1661–1678.

- Tsai TT, Fattori R, Trimarchi S, et al. Long-term survival in patients presenting with type B acute aortic dissection: insights from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection. Circulation. 2006;114:2226–2231.

- Zhang Y, Barocas UH, Berceli SA, et al. Multi-scale modelling of the cardiovascular system – disease development, progression, and clinical intervention. Ann Biomed Eng. 2016;44:2642–2660.

- Sun Z, Chaichana T. A systematic review of computational fluid dynamics in type B aortic dissection. Int J Cardiol. 2016;210:28–31.

- Zhang X, Wu D, Choi JCB, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase levels in chronic thoracic aortic dissection. J Surg Res. 2014;189:348–358.

- Trimarchi S, Nienaber CA, Rampoldi V, et al. Contemporary results of surgery in acute type A aortic dissection: The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:112–122.

- Booher AM, Isselbacker EM, Nienaber CA, et al. The IRAD classification system for characterizing survival after aortic dissection. Am J Med. 2013;126:730;e19–e24.

- Howard DPJ, Sideso E, Handa A, et al. Incidence, risk factors, outcome and projected future burden of acute aortic dissection. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;3:278–284.

- Trimarchi S, Eagle KA, Nienaber CA, et al. Importance of refractory pain and hypertension in acute type B aortic dissection. Insights from the IRAD. Circulation. 2010;122:1283–1289.

- Li D, Ye L, He Y, et al. False lumen status in patients with acute aortic dissection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003172.

- Tsai TT, Evangelista A, Nienaber CA, et al. Partial thrombosis of the false lumen in patients with acute type B aortic dissection. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:349–359.

- Tsai TT, Schlicht MS, Khanafer K, et al. Tear size and location impacts false lumen pressure in an ex vivo model of chronic type B aortic dissection. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:844–851.

- Larsen M, Bartnes K, Tsai TT, et al. Extent of preoperative false lumen thrombosis does not influence long-term survival in patients with acute type A aortic dissection. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e00012.

- Nienaber CA, Kische S, Rousseau H, et al. Endovascular repair of type B aortic dissection: long-term results of the randomized investigation of stent grafts in aortic dissection trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:407–416.

- Brunkwall J, Lammer J, Verhoeven E, et al. ADSORB: a study on the efficacy of endovascular grafting in uncomplicated acute dissection of the descending aorta. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;44:31–36.

- Fattori R, Tsai TT, Myrmel T, et al. Complicated acute type B dissection: is surgery still the best option? A report from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1:395–402.

- Fattori R, Montgomery D, Lovato L, et al. Survival after endovascular therapy in patients with type B aortic dissections: a report from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection. J Am Coll Cardiol Cardiovasc Int. 2013;8:876–882.